The heat of European latitudes during the Eocene period … seem[s] … equal to that now experienced between the tropics.

—CHARLES LYELL, PRINCIPLES OF GEOLOGY

Dinosaurs of the Arctic Jungles

When one thinks of dinosaurs, the first image that pops into mind is that of huge sauropods wandering through warm, lush jungles of conifers and cycads or Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex battling it out in a landscape populated by magnolias and other primitive flowering plants. We hear about the warm climates and dense vegetation of the age of dinosaurs and of the discovery of their remains in tropical and temperate latitudes from Montana to Mongolia to Malawi. Even though Mongolia and Montana are now harsh high-altitude deserts or steppes with blazing hot summers and extremely cold winters, their transformation into the lush landscape of the Mesozoic doesn’t seem beyond the realm of possibility. In the past 20 years, however, one of the more astounding discoveries is the revelation that dinosaurs were abundant even in the polar regions above the Arctic and Antarctic circles, where they would have experienced six months of darkness (see the illustration that opens this chapter).

The first evidence of this amazing discovery was accidental and almost completely overlooked. Exploring along the Colville River (figure 1.1) on Alaska’s North Slope in 1961, a geologist named R. L. Liscomb was mapping rocks for Shell Oil Company and assessing their oil potential, not looking for fossils. He found and collected some huge bones eroding out of the banks of the Colville River. Not unreasonably, he assumed they were from Ice Age mammals, which are found in abundance in the Arctic region. In 1978, another geologist, R. E. Hunter, found clear dinosaur footprints near Big Lake on the Alaska Peninsula. Finally, in 1984 the legendary paleontologist C. A. “Rep” Repenning of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reexamined the bones collected by Liscomb 23 years earlier and realized they were dinosaur bones. (Rep was a good friend of mine and of most vertebrate paleontologists. In 2005, he was tragically murdered in his own home near Denver by a thief who thought he had commercially valuable fossils in his possession.) The announcement of these dinosaur fossils impelled a number of expeditions by paleontologists and geologists to revisit the Colville site and relocate the dinosaur bones in the 1980s and 1990s, all led by Dr. William Clemens from the Museum of Paleontology at the University of California at Berkeley and Dr. Roland Gangloff of the University of Alaska at Fairbanks. Their discovery was startling—thousands of dinosaur bones (figure 1.2) eroding from the riverbanks for miles along the Colville River, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle! In 2007, paleontologists even dug a tunnel into the riverbank (figure 1.3) to excavate the bone bed in greater depth and to recover better-preserved bones that had not been shattered by the freezing and thawing of the permafrost near the surface. The Colville River bones came from the end of the age of dinosaurs, the latest Cretaceous period (for the timescale, see figure 1.3), about 69 million years old, and some of the dinosaur tracks there date to the middle part of the Cretaceous, about 90 to 110 million years ago.

The Colville River localities have yielded at least 12 different species of dinosaurs so far, with the most abundant being the huge 13-meter (40-foot), three-ton duckbilled dinosaurs known as Edmontosaurus. Two other duckbilled dinosaurs, the large-nosed Kritosaurus and the large-crested Lambeosaurus, are also known from the area. Next in abundance are the horned dinosaurs, or ceratopsians, including Pachyrhinosaurus, with its thick, flat horn boss on the nose and broad frill, and the three-horned Anchiceratops, which looked vaguely like Triceratops but was more primitive. There were also pachycephalosaurs, smaller bipedal dinosaurs that had a thick dome of bone in their skull caps that protected their brain. The function of the thick dome is still controversial, although most paleontologists believe it was used for head-butting combat between males of the same species. A tyrannosaur would certainly make an easy meal of a 5-meter (15-foot) pachycephalosaur with no other armor! Finally, there was the ostrichlike herbivorous dinosaur Thescelosaurus, which was about 3 meters (11 feet) long and weighed about 90 kilograms (200 pounds).

FIGURE 1.1 The Colville River dinosaur localities on the North Slope of Alaska. F = footprint; D = femur; T = turtle and tooth-marked clam; O = occipital condyle; H = horn core. (Redrawn from Parrish et al. 1987)

FIGURE 1.2 In the Liscomb bone bed, (A) Kelly May of the University of Alaska Museum of the North excavates a hadrosaur tibia, and (B) museum team members excavate hadrosaur material in a permafrost tunnel. (Photographs courtesy K. C. May, University of Alaska Museum of the North)

FIGURE 1.3 Mesozoic and Cenozoic timescale. Climatic events are in boldface; biotic, in italics.

The predators include the familiar T. rex (known only from a single tooth so far), and a slightly smaller tyrannosaur, Albertosaurus, which is better known from southern Alberta (hence its name). There were also the small lightweight predators known as dromaeosaurs, such as Troodon, Dromaeosaurus, and Saurornitholestes, which looked much like the “raptors” of Jurassic Park fame. All of these dinosaurs are known from beautiful complete skeletons in the Upper Cretaceous Red Deer River badlands of Alberta, so dinosaurs apparently roamed easily between southern Alberta and northern Alaska in the Late Cretaceous.

Today the Colville River sites are only a short distance from the Arctic Ocean and are frozen over from October to May, with temperatures averaging–16°C (–27°F) in January. Even the brief summer is cold and dry, with highs only about 8°C (46°F) and lows around freezing each night. Nothing grows there today except tundra plants, which are adapted to freezing most of the year and must grow rapidly during the short summer months. Finally, the sites are hundreds of miles north of the Arctic Circle and were so during the Cretaceous as well, so the area experienced four to six months of darkness every year. Clearly, the modern climate and vegetation could not support such a huge diversity of large herbivorous dinosaurs, and today the region has only herds of caribou, musk oxen, and Arctic rodents and rabbits.

Indeed, abundant fossil plant remains are preserved not only in the Cretaceous rocks of the Colville River area, but also in eastern Siberia. Most of the plants were conifers, such as the relatives of the living Taxodium (bald cypress), which today are most abundant in the temperate-subtropical wetlands such as the Okefenokee Swamp, the Everglades, and the Mississippi Delta. During the Cretaceous, there were also abundant cycads (“sego palms,” which are actually gymnosperms and not true palm trees). These cycads were more vinelike than their modern stumpy palmlike relatives and may have carpeted the landscape. Another gymnosperm, the ginkgo (“maidenhair”) tree, was very abundant, as were numbers of smaller flowering plants. Based on their spores, ferns grew in great abundance in the understory of these conifers, as did sphenopsids (scouring rushes or horsetails) in the wetter areas. In short, this plant assemblage was a mixture of swampy vegetation with drier upland forests, not too different from the plants in the warm temperate latitudes of North America today—and nothing like the plants that grow in the modern climate of Alaska.

An analysis of the shapes of the fossil leaves gives a mean annual temperature of 5°C (41°F), with summer temperatures above 10°C (50°F) and winter temperatures at or below freezing (Parrish et al. 1987; Spicer and Parrish 1990). Nevertheless, the tree rings of the logs show strong patterns of seasonal growth, with no growth during the four months of darkness. Nearly all the plants were deciduous and dropped their leaves during the warm, dark winters or died off, as do ferns. So even though the climate was much warmer than it is today, the dark winter landscape would have had almost no fresh green plant food available for the herbivorous dinosaurs to eat.

Paleontologists have long puzzled over how such conditions would permit such a high diversity of dinosaurs. Most think that the dinosaurs migrated up from the south during the summer and back down from the north during the winter. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that none of the dinosaur bones shows growth rings indicative of slow growth during the winter dormancy. Most of the dinosaurs were large and mobile, and their fossils have been found from Mongolia and China to southern Texas, so they clearly could walk long distances. However, there are also very small dinosaur teeth in the North Slope faunas, suggesting that smaller nonmigratory dinosaurs were also present, or even juvenile dinosaurs that must somehow have shut down their metabolisms and toughed it out for four months of darkness and near starvation.

Dinosaurs of Darkness Down Under

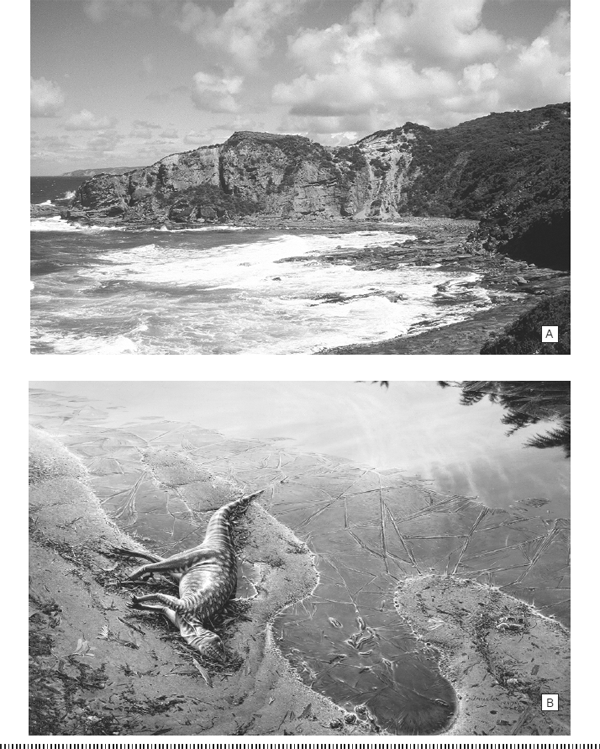

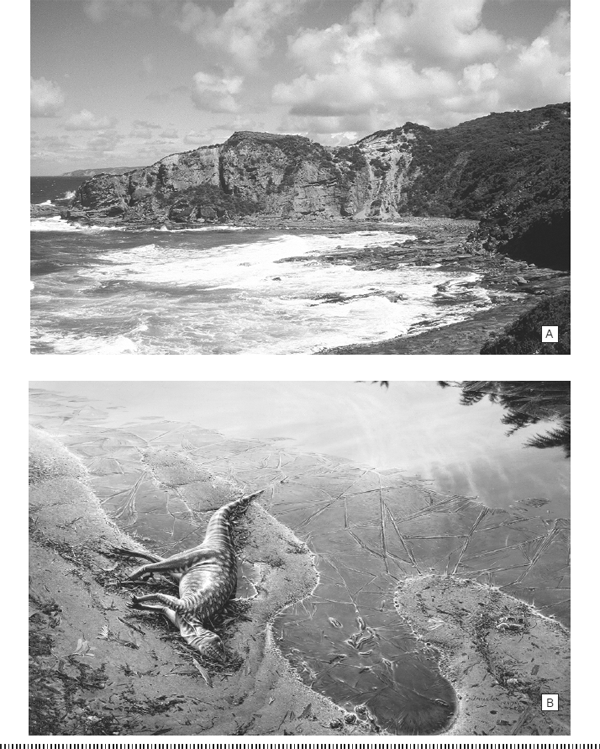

Almost the same story can be told about the Southern Hemisphere in the Cretaceous. Although the Southern Hemisphere dinosaurs are not as abundant as they are in the Arctic, nevertheless there are some important Cretaceous finds here. The first dinosaur fossil finds in Australia were made in 1903 by the pioneering Australian geologist William Hamilton Ferguson, who found a dinosaur claw. Since 1984, my friends Tom Rich of the Victoria Museum in Australia and Patricia Vickers-Rich of Monash University have been working on the problem. Both Tom and Pat were students of my graduate adviser, Malcolm McKenna, at Columbia University. They finished their doctorates in 1973, just a few years before I arrived in the program, and then took positions in Australia. Every austral summer or fall they lead crews to the beach of Inverloch, Victoria, Australia, about 145 kilometers (90 miles) southeast of Melbourne. At a site known as Dinosaur Cove (figure 1.4A), they use dynamite and heavy equipment to tunnel into the overlying beach cliff, then rock saws and large hammers to remove the hard blocks of fossiliferous sandstone and chisel out the precious dinosaur fossils. Years of hard labor have produced a great number of dinosaur fossils, including the little hypsilophodontids Leaellynasaura amicagraphica (figure 1.4B) and Atlascopcosaurus loadsi, the small predatory coelurosaur Timimus hermani, and ostrichlike oviraptorid dinosaurs as well. Two of these dinosaurs were named for the Riches’ children, Leaellyn and Tim.

FIGURE 1.4 Dinosaur Cove in (A) the present and (B) the Cretaceous, with the carcass of Leaellynasaura amicagraphica about to be fossilized. ([A] photograph courtesy T. Rich; [B] painting by P. Trusler, used with permission)

These fossils are much older in the Cretaceous (95 to 110 million years old) than those from Alaska or Siberia, but they were formed in rocks that were slightly more distant from the South Pole (about 80° south latitude). At that time, Australia was still attached to East Antarctica as part of the great supercontinent Gondwanaland, which didn’t completely break up until the Late Cretaceous. Leaellynasaura is the most complete of these fragmentary fossils. It was a small bipedal herbivore, less than a meter in length. Its skull shows enlarged eye sockets and huge optic lobes of the brain, suggesting that it had very large eyes and was adept at seeing in low-light conditions. Detailed examination of the bone histology of Leaellynasaura shows no obvious growth lines, indicating that these creatures were active year round and did not hibernate or become dormant during the long dark winters when no plants were growing. By contrast, the histology of the little predator Timimus does shown pronounced growth lines, suggesting that these animals did become dormant in the winter.

Given these animals’ small size, adaptations for the dark conditions, and the fact that the path to warmer climes to the north was blocked by a great inland sea that covered most of Australia during the Cretaceous, it is unlikely that they migrated away during the dark winters, as has been postulated for the Alaskan dinosaurs. Despite the darkness, the world of the Antarctic in the Cretaceous was not barren, although it was probably cold. Geochemical analysis of the bones suggests temperatures ranging from –5°C to 6°C (23 to 42°F, like that of modern Nome, Alaska), although the paleobotanical evidence suggests a slightly warmer summer temperature average of 10°C (about 50°F, like modern London). The landscape was green and lush (see the illustration that opens this chapter), with abundant ferns and Araucaria trees (Norfolk Island pines or monkey puzzle trees). There were also abundant ginkgoes, cycads, and podocarps, all common during the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous in lower latitudes as well. At this time, angiosperms, or flowering plants, were just beginning to evolve in lower latitudes, so they are rare at high-latitude localities such as Dinosaur Cove. Although most of the plants were deciduous and dropped their leaves or became dormant during the months of darkness, there were some evergreens as well.

In addition to the dinosaurs, fossils of fish, turtles, flying pterosaurs, birds, and amphibians have also been recovered from the site, so it was a rich locality supporting a full range of cold-blooded and warm-blooded animals not found in freezing climates today. Another slightly younger Cretaceous locality near Inverloch has also produced the tiny lower jaw of a shrew-size mammal known as Ausktribosphenos nyktos (Rich et al. 1997), which is more primitive than any living mammal group, including the egg-laying platypus and the pouched marsupials. Indeed, its exact placement within the Mesozoic mammals has long been controversial because its lower teeth seem to be turned backwards relative to any mammal known from the rest of the world. I vividly remember when this specimen was first announced at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) meeting in 1999, and Tom Rich showed it to me. I didn’t know what to make of it!

Both the North and South Poles were much warmer and more lush with vegetation than they are today and supported a diverse fauna of dinosaurs and other vertebrates that lived in four to six months of darkness every winter. Earth as a whole clearly must have been much warmer for its poles to have so much warmth and vegetation. In addition, there must have been no obstacles for the circulation of tropical oceanic waters toward high latitudes to bathe the polar regions and spread the warmth up to the poles, where there is so little sunlight. Indeed, it is well established that the later half of the Mesozoic was a “greenhouse world” with no polar ice caps and high levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Very high sea levels drowned most low-lying continents and flooded them with fish, ammonites, and huge marine reptiles. This “greenhouse of the dinosaurs” prevailed from at least the Middle Jurassic (about 175 million years ago) and began to vanish during the Eocene (about 45 million years ago) (see figure 1.3). How this transformation occurred is the subject of the rest of this book.

But what factors can explain the “greenhouse” conditions of the later Mesozoic? Geologists agree that there was much more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere in the Cretaceous than at any time since then—perhaps 2,000 parts per million (ppm)—almost ten times the present value of about 300 ppm, the level of atmospheric carbon dioxide in our atmosphere until recently (that is, until our burning of fossil fuels in the past century triggered the recent rise in greenhouse gases). Researchers have proposed a number of different sources for this excess carbon dioxide in the Cretaceous. Certainly one of the factors was the extraordinarily high rate of seafloor spreading and volcanic eruptions along midocean ridges. These phenomena not only produced new seafloor and oceanic crust, but released enormous volumes of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from the mantle. Many studies have shown that the Cretaceous had some of the fastest seafloor spreading ever seen, as most of the continents that were once united in the Pangea supercontinent began swiftly to pull apart, producing the Atlantic Ocean and separating Africa from Indian from Australia-Antarctica.

Roger Larson of the University of Rhode Island has also pointed to another potential source of the excess carbon dioxide. Deep under the western Pacific Ocean are huge submarine oceanic plateaus that are completely invisible from the surface of the ocean. In fact, they were unknown to science until the 1950s, when oceanographic voyages began routinely to survey and map the ocean floor and discover its surprising and amazing topography. These plateaus are made entirely of basaltic lavas erupted by huge submarine volcanoes during the Cretaceous. The biggest is the Ontong-Java Plateau in the South Pacific, which erupted 1.5 million cubic kilometers (360,000 cubic miles) of lava in only a million years about 122 million years ago. Others include the Hess Plateau and the Shatsky Rise. Larson points out that the volume of lavas was so immense that it would have released huge amounts of greenhouse gases in the process of eruption. Most geologists think that these huge eruptions were the result of a plume of molten rock coming up from the mantle, punching its way through the oceanic crust, and then erupting on a massive scale. Such plumes are referred to as superplumes because they are much larger than the plumes of mantle-derived magma that are currently underneath Hawaii, Iceland, and Yellowstone National Park. Such monstrous eruptions of mantle-derived lavas and gases, both from the midocean ridges and from the superplumes, are unique to the Cretaceous and go a long way to explaining its high levels of atmospheric greenhouse gases.

The Real “Jurassic Park”

Before we get to the end of the “greenhouse of the dinosaurs,” however, we should look at Mesozoic faunas that were not at such extreme latitudes. One of the most famous of these faunas is the Morrison Formation, a distinctive Upper Jurassic unit made of purple-, gray-, and maroon-banded mudstones that are widespread in the Rocky Mountains. As early as 1877, Arthur Lakes, who taught at what would become the Colorado School of Mines, found gigantic bones in the mountains just west of Denver near Morrison, Cañon City, and Garden Park, Colorado. They were among the first dinosaurs ever reported from west of the Mississippi, including the first good specimen of Stegosaurus, the predator Allosaurus, and a number of skeletons of the huge long-necked sauropods Camarasaurus, Diplodocus, and Titanosaurus. Most of these specimens were collected for Othniel C. Marsh at Yale University, who had a small fortune at his disposal to pay for fossils as well as for collectors out in the western territories. After Lakes wrote to Marsh offering his huge bones for sale, Marsh bought them all and then hired Lakes for the princely sum of $125 a year to continue working for him. Then Marsh sent one of his own men, Benjamin Mudge, from the rich fossil beds of western Kansas to help Lakes collect. Marsh’s men soon cornered the market on large Jurassic dinosaurs in Colorado. Marsh was attempting to outdo his archrival, Edward Drinker Cope of Philadelphia, who battled him at every turn to collect and describe the most spectacular new finds from out west.

Marsh’s men had only begun to collect in Cañon City in July 1877 when they got news from two railroad station agents near Laramie, Wyoming, “Harlow” and “Edwards,” that they had huge bones for sale. Marsh sent legendary Kansas collector Samuel Wendell Williston out to Wyoming to find out about the mysterious discovery of huge bones near Como Station on the Union Pacific railway line. When Williston arrived with a check to buy the bones from “Harlow” and “Edwards,” he found they could not cash the check. The two men were so secretive that they had written using aliases—their real names were William Harlow Reed and Edward Carlin. Such suspicious, paranoid behavior was typical of the time because Cope and Marsh were notorious for stealing each other’s finds and hiring collectors away from each other. Marsh and his men even used code words in their telegrams so that Cope wouldn’t learn of their discoveries.

As soon as Williston had scouted the locality, Como Bluff (figures 1.5 and 1.6), he realized that it was far richer than anything in Colorado. Marsh swooped in with men and money to make sure Cope couldn’t steal the prize. He tried to hire Carlin and Reed to work for him, but negotiations broke down, and Carlin eventually started working for Cope and opened his own excavations. Meanwhile, Williston and Reed opened quarry after quarry in 1878, and Marsh was soon inundated with huge bones that would form the classic bestiary of the Late Jurassic: the sauropods Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, and Barosaurus; the primitive ornithopods Camptosaurus, Laosaurus, and Dryosaurus; numerous samples of Stegosaurus; and several predators, including Allosaurus. Marsh’s collectors worked year round, even into the winter months, quarrying away in blizzard conditions with the temperatures well below freezing.

FIGURE 1.5 Como Bluff, Wyoming, showing the purple- and brown-banded mudstones of the Morrison Formation. Quarry 9, pictured here, is the source of most of the Mesozoic fossil mammals from the area. (Photograph by the author)

FIGURE 1.6 The Rocky Mountain Cenozoic basins, showing the major localities and regions discussed in this book. 1, folded and faulted mountains; 2, Precambrian uplifts; 3, Paleocene basins; 4, Eocene basin sediments; 5, lake deposits. (Modified from King, 1977, Fig. 74).

Marsh’s specimens would eventually come to dominate the public understanding of dinosaurs and fossils, and to create an image of the gigantic saurians that we have had ever since then. Dinosaurs had been discovered in England and in New Jersey before the Morrison bonanza, but they were fragmentary, hard to interpret, and seldom mounted or put on display to fire the public imagination. By contrast, many of the Morrison dinosaurs were known from nearly complete skeletons, so they could be mounted in museums and help the world visualize these gigantic creatures. Marsh’s “Brontosaurus” specimen was one of the first to be mounted in this way (along with a larger “Brontosaurus” skeleton that Henry Fairfield Osborn had mounted at the American Museum of Natural History in New York around 1900). Consequently, “Brontosaurus” became the most famous of all the dinosaurs, the iconic image of these huge beasts. Ironically, the name “Brontosaurus” is no longer valid or used by paleontologists because Marsh himself had already described Apatosaurus 1877 from the same quarries at Como Bluff. He then named “Brontosaurus” in 1879 from another more complete Como Bluff specimen. They are the same animal, as Elmer Riggs realized in 1903. By the rules of zoological names, the first name used takes precedence over later names, so Apatosaurus is the correct name for fossils once called “Brontosaurus.”

Likewise, Marsh got the head of Apatosaurus (“Brontosaurus”) all wrong as well. His original specimen had no skull attached, so he guessed incorrectly that it had a short-faced, high-domed skull like that of Camarasaurus. In the 1970s, however, paleontologists Dave Berman and Jack McIntosh discovered that one Apatosaurus specimen did have a decent skull near the end of its neck, and that skull looked more like the long-snouted Diplodocus.

For many decades after these great Morrison dinosaurs were first put on display, paleontologists would visualize them as slow, stupid, lumbering lizards floating in swamps, with their tails dragging behind them. But in the 1970s a number of paleontologists began to rethink this old idea. Some argued that these dinosaurs were “warm-blooded” and had high metabolisms like birds or mammals. The “warm-blooded” dinosaur controversy raged for more than a decade, but now seems to be resolved. The smaller predatory dinosaurs (such as the “raptors” of Jurassic Park fame) were certainly “warm-blooded” because at their small body size and high levels of activity, they would need a high metabolism to be successful. Indeed, there is good evidence that “raptors” and most predatory dinosaurs (including even T. rex) were covered by a downy coat of feathers for insulation, so these animals were not slow and stupid, but active, smart, and warm-blooded.

The size of the huge dinosaurs such as the long-necked sauropods presents a different problem, however. At such large body sizes, these animals had a relatively small surface area compared to their huge volume and no obvious ways of rapidly gaining or losing heat from their bodies. The living elephant is presented with the same dilemma. At its huge size, it must spend much of its time in water or resting in the shade to dump excess body heat. Its huge ears are radiators that shed heat from its body. Most sauropods would have had even greater difficulties if they were “warm-blooded” and generating body heat from metabolism of food. Instead, such large beasts could not use metabolic body heat at all, but kept warm through the warm climates around them. With their large size, they would have gained or lost body heat only very slowly, so they could obtain a stable warm body temperature by sheer size alone. This strategy is known as inertial homeothermy or gigantothermy and probably characterized all of the larger nonpredatory dinosaurs, including sauropods, stegosaurs, horned dinosaurs, duckbills, and many others.

Thus, we now see all dinosaurs as being much more active and intelligent than we once did. We have evidence from trackways that instead of being slow and sluggish in the swamps, many could move pretty fast. Many dinosaurs, including raptors, duckbills, and sauropods, had specializations in their backbones that enabled them to hold their tails out horizontally like a balancing pole, without ever dragging them on the ground. If you look at a good skeleton of a duckbill dinosaur, you will see the elaborate criss-cross truss-work pattern of ossified tendons in their tail that held the entire structure in a straight, rigid fashion. Likewise, most sauropods had a number of specializations in their neck and tail vertebrae that helped them hold their necks and tails fairly straight out of their bodies, probably in a horizontal position most of the time.

Early paleontologists who collected these Morrison dinosaurs saw the purple-, gray-, and maroon-banded mudstones and the tan river-channel sandstones, and they visualized them as deposits of big, humid swamps. To some extent, this interpretation was biased by the fact that the Morrison was dominated by huge sauropods, and paleontologists thought sauropods were so huge that they needed to be buoyed up by water. More recent studies have negated this old picture, however. Peter Dodson and others (1980) reexamined the sediments of the major Morrison dinosaur localities, and they view the world of the Late Jurassic as a broad floodplain-and-lake system, with seasonal droughts and relatively little standing water. If there had been extensive swamps in the Morrison times, significant coal deposits would have been formed when these swamps turned to stone, but there are none. Dodson and his colleagues (1980) argue that this strongly seasonal floodplain was probably inhabited by migratory herds of large sauropods, which needed to keep moving to find both fresh vegetation after they stripped a region bare and freshwater, which would have dried out locally.

This is the way science operates. Old ideas are constantly challenged, and when new evidence emerges, we need to rethink all the old scenarios. Children’s dinosaur books are out of date if they use the name “Brontosaurus” or portray these animals as dragging their tails and floating in swamps—but that’s the price of progress. Fortunately with the Jurassic Park boom in dinosaur paraphernalia, we are quickly seeing a new generation of dinosaur books that incorporate the current ideas.

Kids and “Dino-mania”

Even though my own research has focused largely on the Cenozoic (the “Age of Mammals”), I’ve had the great privilege of working dinosaur-bearing deposits many times in my career. I’m one of those kids who got hooked on dinosaurs at age four and never grew up. In tenth grade, I already knew where I was going to study paleontology in college, and by the time I reached college I was fully committed to taking every class I could to become a good paleontologist.

I also learned that although dinosaurs were cool, not many new dinosaur fossils were available to work on in the early 1970s. The study of dinosaurs was very crowded with paleontologists competing with each other for the handful of good specimens. By contrast, fossil mammals were just as cool, far more abundant, and better preserved, with many more research opportunities, and the field was nowhere near as overcrowded with other researchers. By my senior year, I was already doing projects in fossil mammals from the Eocene. In my senior year, I was awarded a three-year National Science Foundation (NSF) fellowship, which would pay for my first three years of graduate school no matter where I went. I originally planned to start at the legendary program at Berkeley, the only independent Department of Paleontology in the country at that time (now merged with organismal biology to form the Department of Integrative Biology). I expected to be in Berkeley for two years to earn my M.A., then get my Ph.D. at the even more famous Columbia University program at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. I was accepted to Columbia first and turned it down because I hadn’t heard from Berkeley yet. But then my undergrad adviser, Mike Woodburne (himself a Berkeley alumnus), received a call from the Bay Area. The program was not allowed to take any new students that year because they had so many Ph.D. students who were still not finished after six to eight years or more, and the administration was clamping down on them. I quickly called Columbia and sheepishly asked my future adviser, Malcolm McKenna, if his offer were still good. Luckily, they had held my slot, and the following fall I moved to New York and discovered the amazing world of the American Museum.

When I arrived, the museum was a stunning revelation. I had seen its famous dinosaur halls on my first visit to New York in the late 1960s, but I never realized that far more fossil material lay in storage in the collections that were open only to legitimate researchers. The public displays were just the tip of the iceberg. In the Frick Wing alone, there were seven floors of fossil mammals (chapter 2), two whole basements of dinosaurs, and another basement with nothing but fossil fish. Even more important was the American Museum’s intellectual legacy. The collections included the critical specimens gathered in the 1860s to 1880s by pioneering paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope as well as the crucial collections built up by early-twentieth-century giants of the field Henry Fairfield Osborn, William Diller Matthew, Walter Granger, Barnum Brown, Edwin H. Colbert, and George Gaylord Simpson. Nearly every vertebrate paleontologist alive today can trace their intellectual roots through their graduate advisers and back in time to these men, who trained nearly everyone in the field in the early twentieth century. Even though the American Museum had modern classrooms and labs when I started there, it was also brimming with century-old retired exhibits, models, restorations, and paintings, and even the classroom had a cabinet with the old glass lantern slides that William King Gregory had taught with in the 1920s. The research library included the personal books and journal collections of Osborn and nearly everyone else who had worked there a century earlier, along with Cope’s rock hammer and desk.

Even more impressive was the current intellectual state of the American Museum. I was a student of Malcolm McKenna, widely acknowledged as the foremost expert on fossil mammals in the world and a true genius to boot. (He passed away on March 3, 2008, just as I was finishing this book.) Many of the mammalian paleontologists currently in the major museums across the country were his students at one time or another: Bob Emry at the Smithsonian, Bruce MacFadden at Florida, John Flynn (formerly at the Field Museum in Chicago and now Malcolm’s successor at the American Museum), Rich Cifelli in Oklahoma, Bob Hunt in Nebraska, as well as many others. In fact, nearly all of Malcolm’s highly select group of students (he seldom took more than one a year) went on to success in our profession. No other graduate program can match this track record, where typically only one in ten students who finishes a Ph.D. gets a job.

In addition to Malcolm’s expertise on Mesozoic and early Cenozoic mammals, the American Museum also had Richard Tedford on staff, who knew more about later Cenozoic mammals and localities in North America and Australia than any person alive. Eugene Gaffney, a fossil turtle specialist, occupied the fossil reptile position once held by Barnum Brown and then by Edwin Colbert. In the 1980s, the museum added a dinosaur paleontologist, Mark Norell, and another mammalian paleontologist, Mike Novacek (now provost of science). I was one of the last students to be taught by legendary fish paleontologist Bobb Schaeffer, mentor to many of the fossil fish specialists alive today. In short, the museum had not only immense fossil collections, but immense intellectual capital as well. Even the scientific assistants, such as Earl Manning, John Wahlert, and Henry Galiano, were experts on particular groups of fossil mammals. Earl in particular took me under his wing and taught me more than anyone else did. I also learned a great deal from my brilliant officemates and other grad students, including Dan Chure (now the paleontologist at Dinosaur National Monument), Ronn Coldiron (now an elected official in the Silicon Valley), George Engelmann (now at the University of Nebraska, Omaha), Rich Cifelli, and John Flynn.

In addition to hosting amazing fossils and brilliant minds, the American Museum was the site of a revolution in biology and classification as well: phylogenetic systematics or cladistics. Originally developed by the German entomologist Willi Hennig in the 1950s, cladistics had swept through not only entomology, but also ichthyology and other fields of biology by the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was a radical new way of looking at the classification and phylogeny of organisms wherein the taxonomic groups are based strictly on shared evolutionary specializations and all groups are defined by these evolutionary novelties. Only groups that include a common ancestor and all its descendants are valid, meaning that a traditional group such as “reptiles” is invalid unless it also includes their descendants, the birds.

Cladistics threw out the window all the traditional classification schemes developed over the previous two centuries, but it also solved a much larger number of taxonomic problems. It was soon adopted by nearly every biologist who classified organisms (for a detailed discussion, see Prothero 2003:chap. 4 or Prothero 2007a:128–135). Such a controversial new approach was naturally a highly polarizing influence in a traditional institution such as the American Museum. Originally, only the entomologists and ichthyologists favored cladistics, whereas the mammalogists, ornithologists, and herpetologists were dead set against these ideas. Paleontologists at first rejected some of the more extreme claims (for example, the cladistic assertion that the stratigraphic order of fossils cannot be used to assess their phylogeny), but as time went on, more and more paleontologists came to see the merits of cladistics and adopted it.

Every third Thursday of the month, the American Museum would invite a speaker to its seminar series, the Systematics Discussion Group, where the speaker would be caught in a lion’s den between two opposing camps with fundamentally different philosophies about biology, evolution, and classification. At some meetings, each camp’s members actually sat grouped together on either side of the central aisle, like the Labor and Tory parties in Parliament, and on occasion the cladists wore T-shirts with the “Willi Hennig, Superstar” logo on them. Each meeting started out relatively quietly as the speaker gave his or her talk, but as soon as the questions began, the verbal battles would break out between the two sides of the room. In some cases, these discussions developed into shouting matches, or the opposing parties would call each other names and blame the other side for lying or character assassination. This was no staid, objective way of doing science, as the popular stereotype suggests. Instead, it is typical of sciences where new and controversial ideas are fighting for attention, and the human side of scientists is very apparent through it.

I had heard none of this controversy during my undergraduate education because the ideas were just then taking root and were confined largely to educational and scientific institutions in New York City. But Earl Manning and my grad student officemates quickly had me unlearn some of the old notions I’d been taught as an undergrad and jump into the new way of thinking because it was taught in every class and was dominating the scientific literature we were reading. Soon we were trying to draw cladograms of the entire Mammalia, an exercise that could be done only at the American Museum with its superb specimens of nearly every group of fossil mammals. The biggest breakthrough occurred in 1975, when Malcolm McKenna published a legendary paper that not only proposed controversial ideas about the homologies of mammalian teeth, but also began the process of classifying all mammals in a cladistic framework. Needless to say, this ambitious and dogma-shattering idea was a shock to paleomammalogists all over the world. They all soon saw the advantages, though. Two decades later, by the time Malcolm actually finished and published his life’s magnum opus, a complete cladistic reclassification of mammals (McKenna and Bell 1997), the profession widely accepted this approach.

Needless to say, the late 1970s was an amazing time to be a graduate student: I was learning from the best minds in the profession; both my professors and my fellow students were on the cutting edge of a revolutionary set of ideas that was transforming the fundamentals of paleontology; and I had a huge number of unstudied fossils in the storage floors below me. When I gave my first professional talk at the SVP meeting in Pittsburgh in 1978, I was presenting one of the few cladograms on the entire program. Only a decade later, all systematics talks at the SVP meeting were cladistic, and no one was using the old methods anymore. In addition, the late 1970s brought another revolutionary idea, vicariance biogeography, which was closely tied to cladistics and was polarized along the same lines within the scientific community (for further details, see Prothero 2003:chap. 9).

Although from the beginning I was focused on doing research on fossil mammals, opportunities to study and collect dinosaurs nevertheless came up again and again. In the summer of 1977, Malcolm hired me, his first-year student, and John Flynn, his incoming student, as his field crew. We spent much of the summer picking through washed fossil-bearing matrix from various localities, finding tiny bones and teeth, while Malcolm fed and housed us in his amazing ranch just outside Rocky Mountain National Park near Ward, Colorado. But he also took us on a whirlwind tour of all his favorite Mesozoic and early Cenozoic fossil localities in Wyoming, Colorado, and adjacent states, where we saw and collected from nearly every legendary locality that paleomammalogists read about early in their careers: the Bighorn Basin, Teepee Trail Quarry, Togwotee Pass, Hyopsodus Hill, Darton’s Bluff, Tabernacle Butte, the Green River lake beds with their amazing fossil fish, the Bridger and Washakie basins, the Wind River badlands, Beaver Divide, Bates Hole, Flagstaff Rim, and so on. We visited some important dinosaur-bearing beds that Malcolm had collected over the years, including the Upper Cretaceous Lance Creek Formation in eastern Wyoming, home of Triceratops, and the Upper Cretaceous Fox Hills Formation in central Wyoming, which was chock full of the ossified tendons of duckbill dinosaurs.

The most important stop for me, however, was a visit to Como Bluff, Wyoming, home to some of the best-known Jurassic dinosaurs ever found (see figures 1.5 and 1.6). As discussed earlier, Como Bluff was originally collected by O. C. Marsh’s crews in the late 1870s and had yielded the first complete skeletons of nearly all the famous Jurassic dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation. Dinosaur bone fragments were so abundant that in one area a local rancher had used them to build the foundation of his house, and so Bone Cabin Quarry became famous. A restored “bone cabin” (figure 1.7) still stands along the highway today. In addition to all these famous dinosaurs, Quarry 9 at Como Bluff had produced a number of tiny jaws of shrew-size Jurassic mammals, the first ever reported from North America. Marsh had briefly described them in the 1887, but George Gaylord Simpson had done a more complete job as part of his dissertation in the 1920s. In 1968, Tom Rich (then McKenna’s student at the American Museum), Chuck Schaff, and Farish Jenkins Jr. (then of Yale University) decided to reopen Quarry 9 at Como Bluff and see if better Jurassic mammals could be found, a full century after Marsh’s crew had originally worked there. They headed up a big crew that excavated and handpicked many tons of material to find any of the tiny, pinhead-size Jurassic mammal teeth and jaws. After three hard summers of fieldwork, Tom, Chuck, and their crew had found just a handful of specimens, but they all were of therian mammals (relatives of modern marsupials and placentals), which were supposed to go to Yale according to the agreement worked out before the project. The very few nontherian mammals they had found—members of archaic extinct Mesozoic groups with no descendants—were supposed to go to Tom for his dissertation. Thus, Tom was in a bind. Three years of hard work, and he didn’t have enough specimens for a good dissertation. Malcolm helped him out by handing him a project on North American fossil hedgehogs. Malcolm had been planning to work on it for years, and he had all the specimens and literature already assembled, so Tom needed only to plunge in and study them. Thus, he was able to finish his doctorate in time. Tom and Pat were married and soon on their way to jobs in Australia, so the Quarry 9 collection was left unstudied and sitting in Farish Jenkins’s office when he moved from Yale to Harvard.

FIGURE 1.7 The modern building made of dinosaur bones from the highway tourist trap near the Bone Cabin Quarry area. Pictured are my 2003 field crew (left to right): Matthew Liter, Jingmai O’Connor, Paula Dold, Josh Ludtke, and Francisco Sanchez. (Photograph by the author)

Then Malcolm mentioned during his “Evolution of Mammals” class in 1977 that these Quarry 9 specimens had finally returned to the American Museum after sitting at Yale and Harvard for almost a decade. I was the first to ask if I could study them as my class project. This request soon led to trips up to Harvard to see the rest of the specimens, plus Marsh’s Yale specimens (also on loan at Harvard) and stereophotomicrographs of the Late Jurassic mammals of England taken by A. W. “Fuzz” Crompton of Harvard. I eventually saw every Jurassic mammal fossil known from England and North America, so my small class project expanded into a much larger master’s thesis and was eventually published in 1981 in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, one of the oldest and most respected museum journals in the world. I was particularly pleased that among the specimens was one new genus and species, which I dubbed Comotherium richi in honor of Tom’s work (figure 1.8).

While I was up at Harvard, I ran into Richard Estes of San Diego State University. He was then the reigning expert on Mesozoic lizards and other small reptiles and amphibians. I was trying to identify the lizards that Tom Rich, Pat Rich, Chuck Schaff, and crew had collected from Quarry 9, and Dick immediately realized what they were. We wrote up our results, and they were published in 1980 in the British journal Nature—my first scientific paper in one of the foremost journals in all of science. I also poked through the rest of Tom’s 1968–70 collection and found an ear bone of a Jurassic mammal that I also wrote up and published. A year later, “Dinosaur Jim” Jensen of Brigham Young University approached me to work on an upper arm bone of a Jurassic mammal that he had found in his famous Dry Mesa Quarry in western Colorado, the source of Ultrasauros, one of the largest dinosaurs that ever lived. That project too was written up, illustrated with my own hand drawings of the fossil, and published.

FIGURE 1.8 The upper molars of the Jurassic mammal Comotherium richi, a new species I had the privilege of naming in honor of Tom Rich in my master’s thesis and first major publication: (A) crown view; (B) outside view; (C) inside view. (Drawing by C. R. Prothero, from Prothero 1981)

After all this research, however, it was clear to me that there was no future for me in Mesozoic mammals. There were no additional specimens to study in the early 1980s, and the field was already crowded with people who were working on what specimens were already available. Plus, the pinhead-size teeth and jaws required a great deal of microscope time to study, and long hours at the microscope were difficult for me with my thick glasses and extreme myopia. So I left Mesozoic mammals behind and moved on to larger mammals, such as rhinos and camels (which don’t require a microscope to be seen), and never looked back. Ironically, beginning in the 1990s and continuing now, there has been an explosion of new specimens, new research, and new researchers, so this field is now booming in a way that we could never have imagined when I worked on these fossils in the late 1970s (Kielan-Jaworowska, Cifelli, and Luo 2004). I’m pleased to see the current workers in Mesozoic mammals cite my early work on cladistics of therian mammals and honored when they ask me for my opinion on the matter, but I’ve moved on and don’t work on them anymore.

Since 1980, I have focused primarily on Cenozoic mammals and rocks. In the summer of 1988, however, my field crew and I did some research in the Upper Cretaceous Williams Fork Formation of western Colorado in the Piceance Basin just north of Rangeley. This research was Dave Archibald’s ongoing project at San Diego State University, and he invited my crew and me to visit and take paleomagnetic samples (chapter 3). It was a very interesting experience. The rocks looked very different from the Cenozoic beds and were full of coal seams and dinosaur bones. We helped excavate a partial skull of Triceratops and saw tyrannosaur bones again and again. The results were analyzed that same summer at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) lab but still haven’t been published twenty years later because of delays by various coauthors!

A Blast of Gas from the Past

Even though the dinosaurs vanished at the end of the Cretaceous (chapter 5), the “greenhouse of the dinosaurs” persisted for at least another 20 million years into the late middle Eocene. In fact, the early Eocene was in many ways warmer and more tropical than even the peak of the Cretaceous “greenhouse” world. Once again, the best evidence comes from fossil vertebrates and plants. The famous lower Eocene beds of the Bighorn and Wind River basins of Wyoming and of the Williston Basin of North Dakota and Montana yield evidence of warm tropical forests full of tree-dwelling and leaf-eating archaic mammals as well as abundant crocodilians and pond turtles.

The Arctic and Antarctic also yield fossil plants that suggest cool temperate conditions even north of the Arctic Circle and south of the Antarctic Circle, where there is darkness for many months of the year. The flora of this region was a paratropical rain forest that included many large conifers (pine trees, the giant Sequoia, and the dawn redwood Metasequoia), other evergreens, and deciduous trees (elms, oaks, Liquidambar, ginkgoes, Viburnum, and the bald cypress, Taxodium). These forest plants somehow adapted to many months of darkness. However, the temperatures were quite warm above the Arctic Circle in the Eocene, with mean annual temperatures between 19 and 25°C (66 and 77°F) (Wolfe 1980, 1994).

In the 1970s, Malcolm McKenna, Mary Dawson of the Carnegie Museum, and Howard Hutchison of Berkeley led several expeditions to the Canadian Arctic and Greenland to find early Eocene fossils from this region, with amazing success (figure 1.9). During their expeditions to Ellesmere Island in the Canadian High Arctic, they found early Eocene faunas that included abundant crocodilians, monitor lizards, and turtles, as well as gar and bowfin fish, which could not have survived in temperatures that freeze for very long. They discovered a variety of fossil tapirs, primitive horses, rhinos, rhinolike brontotheres (see the drawings that open chapter 4), primates, rodents, fossils related to the living colugos, or “flying lemurs,” and smaller mammals, all of which are consistent with the dense forests, abundant fruit fossils, and coal swamps preserved along with them. These mammals show a great similarity to early Eocene faunas of North America and Europe. Indeed, it was such a warm time and so free of polar ice that considerable migration of mammals must have taken place between Europe and North America using Greenland and Iceland as part of the land corridor to cross the North Atlantic, which was much narrower then. When the early Eocene mammals of Europe and North America were first described, paleontologists noted how similar the primates, horses, and many other groups in both places were and postulated that there must have been some easy way for them to travel across the Atlantic. But now we can see that the warm polar climates made the corridor across the North Atlantic through Greenland and Iceland much easier to cross in the early Eocene than it would ever be again.

FIGURE 1.9 Malcolm McKenna collecting fossils from the Eocene beds on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic. (Photograph courtesy J. Eberle)

For the best picture of the early Eocene, however, we need to go to the basins of the Rocky Mountains (see figure 1.6): the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming and Montana, the Wind River and Powder River basins of Wyoming, the Williston Basin of Montana and North Dakota, and the San Juan Basin of New Mexico (figure 1.10A). These immense bowls filled with thousands of feet of Paleocene and Eocene sediment were warped downward as the Rocky Mountains buckled, folded, and faulted upward starting in the latest Cretaceous. The Rocky Mountain basins provide by far the best terrestrial record of this fascinating time. Nevertheless, the collecting can be challenging. Most of the fossils are isolated teeth and jaws of very small shrew-size to cat-size mammals, so you must collect them on your hands and knees (figure 1.10B), with your nose about a foot from the ground, or you will miss them entirely. Over the course of a century, collectors such as Matthew, Simpson, and Granger of the American Museum and Glenn Lowell Jepsen of Princeton University made the tiny fossils of these Paleocene and early Eocene beds their top priority. One of Jepsen’s former students, Phil Gingerich (see figure 1.10B) of the University of Michigan, has spent almost his entire professional career continuing this collecting effort. He has also trained a whole generation of students in the Bighorn Basin, including Tom Bown (formerly of the USGS), Ken Rose (Johns Hopkins University), Dave Krause (State University of New York at Stony Brook), Scott Wing (Smithsonian), Greg Gunnell and Cathy Badgley (University of Michigan), Jonathan Bloch (University of Florida), Will Clyde (University of New Hampshire), Ross Secord (University of Nebraska), and many others. As a consequence, there are now enormous collections of nearly all the mammals found in the Paleocene and early Eocene of the Rocky Mountain region of North America, and they are among the best-documented and best-studied mammalian fossils in the world.

From these decades of work in the Bighorn Basin and elsewhere, Gingerich and his former students have painted a detailed picture of life in the early Eocene. The barren wastelands of the Bighorn Basin today are hot and dry in the summer and plagued by numbing cold and blizzards in the winter, with a mean annual temperature of only 5°C (41°F) and a spread of more than 33°C (90°F) between daily extremes. In the northern High Plains, it is not unusual for a hot spring or fall day with temperatures higher than 32°C (90°F) to drop below freezing suddenly as an Arctic cold front moves in. In the early Eocene, however, Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota were mantled by dense tropical forests not too different from those found in Central America today. Mean annual temperatures were as high as 21°C (70°F), and the mean cold-month temperature was only 13°C (55°F). The fossil plants also suggest a very wet climate, with annual rainfall exceeding 1.5 meters (60 inches). The forests formed a multistory canopy like the rain forests do today, with abundant vines and lianas hanging down, perfect for Tarzan to swing on. Many of the fossil plants are from tropical groups that are intolerant of freezing, including citrus, avocado, cashew, and pawpaw trees.

FIGURE 1.10 (A) Panorama of the Paleocene–Eocene beds of the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. (B) Collecting the tiny jaws and teeth from the Paleocene and Eocene requires crawling on your hands and knees, with your eyes just a foot off the ground, or you’ll miss the fossils entirely. This crew from the University of Michigan in July 1977 is scouring the ground like a human vacuum cleaner to pick up every single tiny jaw or tooth. The man with the pith helmet in the left background is Phil Gingerich, leader of the group. The woman to his left is Margaret Schoeninger, then a Michigan student and now a professor of anthropology at the University of California, San Diego. The man in the left foreground is Ken Rose, then a Michigan student and now a professor at Johns Hopkins Medical School. The man with the dark shirt on the right behind the stooping student is David Krause, then a Michigan student and now at the State University of New York, Stony Brook. The man in the middle with the visor is John Flynn, then Malcolm McKenna’s student at Columbia and now his successor at the American Museum of Natural History. (Photographs by the author)

Living in these dense forests was an assemblage of animals that most people would not recognize (figure 1.11). Most familiar would be the abundant crocodilians, pond turtles, and snakes, which love the warmth of the tropics but cannot live in Montana or Wyoming or North Dakota today due to the long, freezing winters. The assemblage of mammals, however, was composed mostly of extinct groups that are unfamiliar to the nonspecialist. They include a variety of very primitive insectivores, lemurlike primates that lived in the tree canopy but also occupied a rodentlike niche as well, and the archaic group of rodentlike, egg-laying mammals known as multituberculates, which were survivors from the Triassic. Down on the ground, nearly all the beasts were archaic hoofed mammals that had teeth suitable for eating a diet of soft, leafy vegetation, along with some mammals that are now extinct and have no modern relatives. The larger predators were mostly from the now archaic extinct group known as creodonts, and true carnivorans (members of the living order that includes dogs, cats, bears, weasels, and seals, among others) were about the size and shape of a raccoon. But there were no really large lion- or bear-size mammalian predators. Instead, that role was taken by huge, 3-meter (9-foot) predatory flightless birds, such as Diatryma in North America and Gastornis in Europe.

FIGURE 1.11 Diorama of life during the early Eocene. The trees are full of lemur-like primates. On the ground, the huge predatory bird Diatryma eats early horses. (Drawing by U. Kikutani)

What could cause the early Eocene world to be so warm, even warmer than it was during the Cretaceous heyday of the “greenhouse of the dinosaurs”? Models of carbon dioxide values place the atmospheric level around 1,000 ppm, about three times the present level, but less than half that of the warmest greenhouse of the Cretaceous (Berner, Lasaga, and Garrels 1983; Berner et al. 2003). Other geologists (Sloan and Rea 1995; DeConto and Pollard 2003) also see high carbon dioxide levels as the chief culprit for these greenhouse conditions. But some paleobotanists have looked at the stomata, the tiny pores found on the undersides of leaves that plants use to exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide with the outside atmosphere (figure 1.12). During conditions of high carbon dioxide, plants make fewer stomata because they can get carbon dioxide for photosynthesis much more easily and lose less water in the process. Conversely, low carbon dioxide conditions trigger leaf growth with more stomata. Dana Royer and colleagues (Royer et al. 2001; Royer 2003) found that the stomatal density on living fossils such as the dawn redwood Metasequoia and Ginkgo have been fairly constant since the Cretaceous, which suggests that the carbon dioxide level was not that much higher in the early Eocene. Greg Retallack (2001) looked at plant cuticles and found evidence that the carbon dioxide level was only slightly higher than modern levels. Paul Pearson and Martin Palmer (1999, 2000) have demonstrated that the carbon dioxide balance and pH profile in the world’s oceans was consistent with an atmospheric carbon dioxide level only slightly higher than we have today.

So if carbon dioxide isn’t the chief culprit for explaining early Eocene greenhouse conditions, what is? A number of geologists (e.g., Sloan et al. 1992) point out that methane, “natural gas” or “swamp gas” (CH4), is also an important greenhouse gas and a much more effective explanation of the early Eocene warming than carbon dioxide is. In 1991, detailed studies were made of the carbon and oxygen chemistry of deep-sea cores that spanned the Paleocene–Eocene boundary about 55 million years ago (Kennett and Stott 1991). It had long been known that at this time there was a major extinction in the benthic foraminifera, the microscopic organisms that lived on the sea bottom, but otherwise there was no evidence of a big mass extinction in other organisms. But these new high-resolution cores showed the interval in great detail and clarity. It was soon apparent that the extinction and the sudden change in ocean chemistry was much more abrupt than previously suspected. Some estimates suggest that the change took place in much less than 10,000 years and that average temperatures in the world ocean abruptly rose by 4°C (about 8°F). Such a rapid and extreme change in ocean chemistry and temperature could not be explained by gradual movement of continents or rearrangement of oceanic currents. Instead, another source was needed.

In 1993, oceanographers discovered that there were huge amounts of methane frozen in little ice cages known as methane hydrates or methane clathrates (Kvenvolden 1993). These chemicals were naturally trapped in the pore water of oceanic sediments, where they remained frozen as long as ocean bottom water temperatures were below 5°C (41°F). They occur in huge volumes today in the continental margins, estimated at about 11 trillion trillion grams (about 500 billion trillion pounds), all trapped in a semistable state as long as the oceans remain cold enough. But with the warming during the Paleocene, this frozen methane would have melted and been suddenly released into the world’s oceans, killing mostly sea-bottom-dwelling benthic organisms, then causing the planet’s oceans and atmospheres to be saturated with natural gas and driving the climate into a “supergreenhouse.” Since 1995, geologists have visualized this scenario for the Paleocene–Eocene boundary (Dickens et al. 1995, 1997; Thomas and Shackleton 1996; Dickens, Castillo, and Walker 1998; Thomas et al. 2002). This “blast of gas from the past” apparently warmed the planet so fast that most bottom-dwelling marine life could not survive, and the shallow marine and terrestrial realms experienced record warmth and plant growth. Although the big excess of methane was gradually reabsorbed and oxidized to carbon dioxide, its effects were present for much of the early Eocene.

FIGURE 1.12 The stomata of the undersides of the leaves of the dawn redwood (Metasequoia): (A) in an Eocene example, the clear oval-shaped cells are the stomata; (B) modern Metasequoia. The density of the stomata is slightly less in the Eocene than in the modern example, suggesting that the atmosphere was richer in carbon dioxide during the Eocene than it is today. (Photographs courtesy G. Doria)

This “methane burp” was felt even on land. Not only did it trigger global warming and intense tropical plant growth almost to the poles, but it can be seen in the chemistry of the teeth of early Eocene mammals and even in the soils. Their chemical composition shows the same abrupt shift to light carbon-12 that we see in marine sediments and fossils, so this event was global. In fact, this chemical isotope signal is universal at the Paleocene–Eocene boundary, so the boundary is pegged to this marker rather than to some local change in the fossils. And right after the carbon isotope spike is when we see the maximum migration of mammals back and forth between Eurasia and North America. For example, another marker of the early Eocene in the Bighorn Basin and elsewhere in North America is the first appearance of primitive horses, rhinos and tapirs (perissodactyls), even-toed hoofed mammals (artiodactyls), advanced lemurlike primates (adapids and omomyids), and (slightly earlier) rodents, all from more primitive relatives in Eurasia. Thus, the “blast of gas from the past” is the final piece of the puzzle, explaining not only why the early Eocene polar regions were so warm and such a good corridor for mammal migration, but also how these animals managed to cross the North Atlantic across Greenland and Iceland for the first and last time.

I vividly remember many conversations with Malcolm McKenna about this very topic because it was central to work he had been doing since his undergrad days. He was the pioneer who first worked on the early Eocene mammals of northwestern Colorado for his dissertation in the 1950s, found the Arctic mammal fossils, explored Greenland for Eocene mammals, and spent a great deal of time puzzling over the incredible similarities between early Eocene mammals from Europe and those from North America, and over how they might have traveled across the North Atlantic. I’m sure he was very pleased in his later years to hear about all these past developments, which have added a final piece to this amazing puzzle.

Further Reading

Aubry, M.-P., S. G. Lucas, and W. A. Berggren, eds. 1998. Late Paleocene–Early Eocene Climatic and Biotic Events in the Marine and Terrestrial Records. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dickens, G. R., J. R. O’Neill, D. K. Rea, and R. M. Owen. 1995. Dissociation of oceanic methane hydrate as a cause for the carbon isotope excursion at the end of the Paleocene. Paleoceanography 10:965–971.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. L. Cifelli, and Z.-X. Luo. 2003. Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ostrom, J. M., and J. H. McIntosh. 2000. Marsh’s Dinosaurs: The Collections from Como Bluff. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Parrish, J. M., J. T. Parrish, J. H. Hutchison, and R. A. Spicer. 1987. Late Cretaceous vertebrate fossils from the North Slope of Alaska and implications for dinosaur ecology. Palaios 2:377–389.

Prothero, D. R. 2003. Bringing Fossils to Life: An Introduction to Paleobiology. 2d ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Prothero, D. R. 2006. After the Dinosaurs: The Age of Mammals. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Rich, T. H., and P. V. Rich. 2000. Dinosaurs of Darkness. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Skelton, P. 2003. The Cretaceous World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, D. J., J. C. Zachos, T. J. Bralower, E. Thomas, and S. Boharty. 2002. Warming the fuel for the fire: Evidence for thermal dissociation of methane hydrate during the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Geology 30:1067–1070.

Ward, P. D. 2007. Under a Green Sky: Global Warming, the Mass Extinctions of the Past, and What They Can Tell Us About Our Own Future. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

Wing, S. L., P. D. Gingerich, B. Schmitz, and E. Thomas, eds. 2003. Causes and Consequences of Globally Warm Climates in the Early Paleocene. Geological Society of America Special Paper no. 369. Boulder, Colo.: Geological Society of America.

Panorama of the Big Badlands looking east from the top of Sheep Mountain Table in the western end of the Big Badlands. (Photograph by the author)