Three

Dumb History

Those wishing to become British citizens are required to take the “Life in the UK” test, a set of questions about British history and culture. Here are some sample questions:

• In the UK, April 1 is a day when people play jokes on each other (true or false).

• What flower is traditionally worn by people on Remembrance Day? (lily, daffodil, iris, or poppy).

• Which landmark is a prehistoric monument which still stands in the English county of Wiltshire? (Stonehenge, Hadrian’s Wall, Offa’s Dyke, or Fountains Abbey).

By design, the questions are easy (the correct answers are true, poppy, and Stonehenge). The grading is easy too. A score of seventy-five percent correct is enough to pass. I surveyed British residents on a sample of the “Life in the UK” questions. About fourteen percent would have failed the test, scoring less than seventy-five percent correct.

Is the glass half empty or half full? Those scores were actually better than those in a 2011 Newsweek survey of one thousand Americans asked questions on the US citizenship exam. Thirty-eight percent of Americans flunked. Most couldn’t say who was president during World War I (Woodrow Wilson) or identify Susan B. Anthony as an activist for women’s rights. About forty percent didn’t know the countries the United States fought in World War II (Japan, Germany, Italy). A third couldn’t name the date the Declaration of Independence was adopted (July 4, 1776). Six percent were unable to circle Independence Day on a calendar.

Such findings have mobilized public opinion. In 2014 Arizona governor Doug Ducey signed a law requiring that high school students be able to pass the citizenship test in order to graduate. An organization known as the Civics Education Initiative hopes to enact similar laws in all fifty US states.

Here’s the thing: it’s easier to rally support for well-meaning mandates than it is to figure out how to teach more effectively than we already do. Civics has always been a bulwark of education. Should teachers place less emphasis on reading, maths, and computer skills in order to focus on how a bill becomes a law? The vast reserve of ignorance is not reduced so much as shifted around.

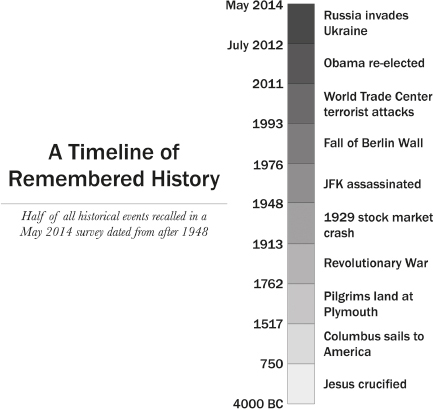

Half of Subjective History Happened Since 1948

I did a survey in which US participants were asked to name “important news or historical events” that took place within specific time frames. These frames ran from 3000 bc to the present and covered single years, decades, centuries, and millennia. The time frames were each presented to a different randomized group so that no one was overwhelmed.

The survey took place in May of 2014. Eighteen percent of participants were unable to name any news or historic event that had happened in the previous calendar year, 2013. Another eleven percent gave a wrong answer.

Survey subjects did about as poorly in naming an event from 2012, and the recall rate for 2011 plummeted to thirty-six percent. That’s right—most people couldn’t remember anything of general importance that had happened three years prior to the survey’s calendar year. There was a similar result for 2010.

A sizable proportion of responses did not concern news so much as sports, weather, crime, and celebrity fluff. Some mentioned sports victories; hurricanes and floods; high-profile murders; celebrity deaths and scandals. These were counted correct as long as the date was right.

There were two ways an answer could be wrong. A few gave events that never happened, such as “President Nixon impeached.” (Nixon resigned to avoid that ignominy.) The more common type of wrong answer was assigning a real event to an incorrect time frame. There were those who put the death of Osama bin Laden in 2012 or 2010 instead of 2011. That’s understandable. The general consensus is that there’s less need to memorize dates now that we’ve got Google and that it’s sufficient to have a general sense of what came after what. But many in my survey didn’t. Some said that Columbus sailed to America in the 1600s and that the Ice Age was in the first millennium ce.

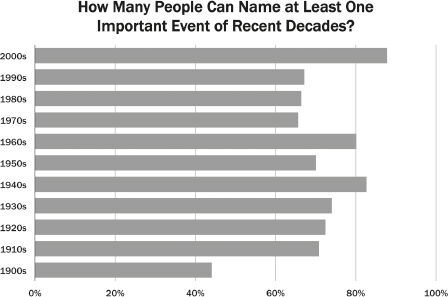

Eighty-eight percent of my sample could name an event that happened in the decade 2000–2009. The most popular answer was the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Recall rates dropped to about two-thirds for the 1990s, 1980s, and 1970s.

Memories perked up for the trippy 1960s (eighty percent), sagged back for the boring 1950s (seventy percent), and rebounded (eighty-four percent) for the 1940s. Most could recollect something about Hitler, Pearl Harbor, the Holocaust, or Hiroshima.

Then recall trended downwards. More than half of respondents were unable to name a single important historical event of the first decade of the twentieth century (1900–1909).

On to centuries.

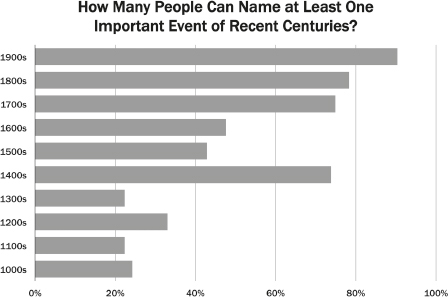

Seventy-eight percent could name something that happened in the 1800s (the Civil War and the end of slavery were the most popular responses). Recall was almost as good for the 1700s (the US Revolutionary War and Declaration of Independence). But most could not name a single event of the 1600s.

A lot happened in that century. The Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. There was the English Civil War and the Salem witch trials; the death of Shakespeare and the birth of Bach; the invention of the telescope and the beginnings of modern science in the persons of Galileo, Kepler, and Newton. None of these occurred to more than half the sample.

A few dates are burned into schoolroom memory, one being 1492. That was enough to produce a spike in recall for its century. Four out of five who were able to supply an event for the 1400s named Columbus’s voyage. But most drew a complete blank for the centuries of the later Middle Ages.

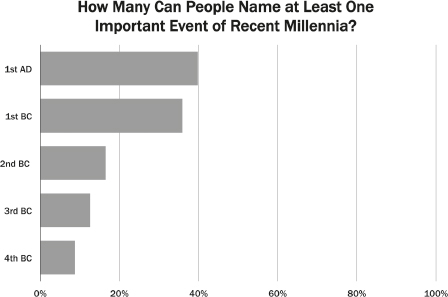

From ad 1000 and back, I merely asked for events that happened in a given millennium. I didn’t count on volunteers understanding admittedly confusing terms such as “first millennium ad.” The survey asked for “an important historical event that happened in the years ad 1 to ad 999.”

You might think it would be all but impossible for a person who understood the question to not be able to name something that happened in the first millennium ad (such as the life and death of Jesus and the decline and fall of Rome) or bc (classical Greece, Cleopatra). Most could not.

Historians infer that Jesus was born in either 6 or 4 bc. Thus the birth of Jesus fell in the first millennium bc. This threw a few people and accounted for some wrong answers, but not enough to change the results much.

Most of the earth’s surface was literally prehistoric before 1000 bc, so it’s not surprising that few were able to name any historic events for the earliest millennia surveyed. The correct answers mainly had to do with Egypt (building the Pyramids), the Old Testament (the Exodus of the Jews, King David rules Israel), and Stonehenge.

Some participants were able to name multiple events for each time frame. I collated all the remembered events (including those that were assigned to a wrong time frame) and used this data to create a timeline of subjective history. The midpoint of remembered history—splitting the timeline in half—is 1948. In very rough terms, it seems that people recall as much that happened after 1948 as before it—going back to the beginnings of civilization. This is another distorted mental map. Here the timeline’s scale is weighted by the number of recalled events.

In making personal and collective decisions, we place too much weight on what has happened in the very recent past. You see this in the reactions to the world’s catastrophes: mass shootings, wars, earthquakes, stock market crashes, terrorist attacks, economic depressions, and epidemics. After each dire event there are calls to be better prepared the next time—prepared, that is, for the thing that just happened. We fail to prepare for predictable challenges and catastrophes that have happened many times before—just not lately.

Forgetting the Presidents

For much of his career, Henry Roediger III has been studying how Americans forget their presidents. He came to this topic by accident. In some psychological experiments, it is useful to interpose a filler task in between the tasks of interest to the researchers. During one experiment, as a filler task, he tried asking undergraduates to write down all the US presidents they could remember in five minutes. The average Purdue or Yale student, he found, could recall only seventeen presidents out of the thirty-six or thirty-seven who had held office up to that point. This research, published in 1976, spanned the Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford administrations.

Roediger, now at Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri, was not trying to make another case for the cultural illiteracy of students. His interest was human memory, and he found that there was huge variation in recall rates for individual presidents. Nearly everyone named Washington, Lincoln, and the few most recent presidents. Very few, less than twenty percent, remembered obscure presidents such as John Tyler and Chester A. Arthur.

Of course, you might argue that some presidents are more important, more worthy of being remembered. But Roediger made a chart that challenged this notion. He put the presidents in chronological order (on the x axis) and charted their recall rate (0–100 percent, on the y axis). This produced, very roughly, a U-shaped curve. The students best remembered the first few presidents and the few most recent ones. In between those two poles stretched a great slump of the forgotten, with the major exception of Lincoln, who had a very high recall rate (the U curve was actually a kind of W, rounded on the bottom).

Roediger and Robert G. Crowder identified this as a serial position effect. When memorizing a list, people best remember the first few items and the last few items. They are least likely to remember items a little more than halfway from the start of the list. In 2015, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and Chester A. Arthur occupy that blind spot of memory.

Of course, with any list there are going to be items that are more memorable for reasons having nothing to do with their position in the list. Lincoln won a war that split and reunited the nation; he abolished slavery, an action that still fascinates and resonates; his dramatic assassination (in a theatre) is part of a tale taught to every American schoolchild. It’s easy to see why Lincoln is an exception to the serial position effect. More surprising is that the few presidents before and after him were also better remembered than average, a Lincoln halo effect that especially benefited his successors Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant.

Roediger has been repeating the presidents experiment over the course of four decades with similar results—aside from the progressive slump of recent presidents into obscurity. In a 2014 experiment Roediger and K. A. DeSoto enlisted the participation of adults of all ages and found that age makes a big difference: people are far more likely to name presidents whose administrations they have lived through. Less than a quarter of Generation X participants—those born from the early 1960s to the early 1980s—named Eisenhower. This isn’t to say that they’d never heard of Eisenhower but that he didn’t come to mind when they were trying hard to think of US presidents. This tells us something about how future generations will think of Eisenhower—or rather, not think of him.

The gradual forgetting of presidents appears to be predictable. By 2040, Roediger forecasts, less than a quarter of the population will be able to remember Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Jimmy Carter. One may imagine that certain presidents are exceptions, as Lincoln is—but usually they’re not. Roediger began his experiments around the time of Watergate. It then seemed to him that Gerald Ford’s status as the first president who was never elected to that office had earned him a permanent place in history and memory. The distinction counts for little now, and Ford has slid predictably into obscurity. After Roediger mentioned this fact in interviews, a spokesperson for the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum contacted him, saying attendance at the institution was declining—did Roediger have any suggestions?

Reminiscence Bump

Beloit College’s Mindset List, published annually since 1998, gently warns professors of dated cultural references that will be meaningless to the incoming class. The class of 2016 has “never seen an airplane ‘ticket’…Robert De Niro is thought of as Greg Focker’s long-suffering father-in-law, not as Vito Corleone or Jimmy Conway.”

Even the teaching of history must, to some degree, accommodate the short memories of youth. Historians wrestle with what is relevant and what can be dropped from the syllabus. There are, however, no sharp lines between nostalgia and cultural history. Should young people know who Billie Holiday was? Groucho Marx? The Kray twins?

A disproportionate share of the memories that we have of our own lives are from adolescence and early adulthood, between the ages of ten and thirty or so, a tendency termed a reminiscence bump. These memories include the joys and pains of puberty, school and university, first love, first job, and first apartment. In contrast we remember nothing of infancy and little of early childhood. The middle-aged remember relatively little of what happened in the great valley of memory yawning between about age thirty and the very recent past. We thus have a biased perception of our own lives, one dominated by the two decades spent in an advertiser-prized demographic.

Danish psychologists Jonathan Koppel and Dorthe Berntsen have found that the reminiscence bump applies to world events as well. People are more likely to remember news events that occurred when they were between around ten and thirty years old. It may not be true that those who remember Woodstock weren’t there, but it’s a safe bet that they were between ten and thirty years old when it happened.

The participants in my history survey were adults, between twenty and seventy years old. Twenty-year-olds are in the middle of their golden memory zone right now. For seventy-year-olds, that zone is forty to sixty years in the past. You would therefore expect the surveyed public to have relatively good memories of events stretching back as far as sixty years. In fact, “living memory” commands about half the subjective timeline, compressing everything else into the other half.

The goal of history class—to provide a broad perspective, to introduce us to the great world that existed before we were born—entails an uphill battle against the realities of memory and attention spans.

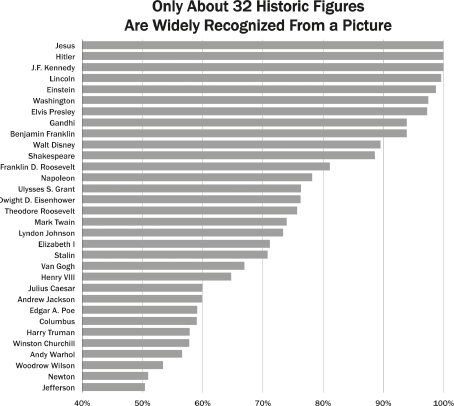

The Thirty-Two Faces of History

History is not just about names and dates. Shakespeare, Queen Victoria, and Einstein live for us today a little more vividly because we can call to mind their faces, preserved in portraits that have become part of collective memory. I wondered how many historic faces are generally known to the public. Nearly everyone can identify Napoleon, Washington, and Lincoln, but there are surprisingly few people who have achieved that level of fame. They are far outnumbered by important personages whom most have heard of but can’t recognize from a headshot. Furthermore, almost everyone can recognize contemporary entertainers and athletes better than they recognize historical figures. Consequently any estimate of the number of widely recognized faces from “history” depends on exactly where you draw the line between historical figures and contemporary celebrities.

I tested facial recognition of nearly all the top one hundred historical figures on a list published by Steven Skiena and Charles B. Ward in 2013. Skiena and Ward claimed to rank historical figures “just as Google ranks web pages, by integrating a diverse set of measurements about their reputation into a single consensus value.” Their method drew heavily on Wikipedia entries: how long the entries are; how often they are viewed; how many links point to them. You may debate how valid this method is. For my purpose the important thing is that it casts a wide net. The top ten on the list are Jesus, Napoleon, Muhammad, Shakespeare, Lincoln, Washington, Hitler, Aristotle, Alexander the Great, and Jefferson. (All are male, as are most Wikipedia editors.)

I asked American survey participants to identify a tightly cropped headshot, 160 pixels square, of each figure. I made the survey as easy as possible, using the most iconic and recognizable portraits I could find. Of course, the features of some of history’s most influential people have gone unrecorded, but a portrait does not have to be authentic to be recognizable. Pictures of Jesus are pure fantasy. Despite that, people have a pretty clear idea of what Jesus is “supposed” to look like. The most iconic image of Christ is one painted by the otherwise obscure twentieth-century religious illustrator Warner Sallman. His Head of Christ was mass-produced as prints and greeting cards, starting in 1941. The Jesuses you see in films and South Park are ultimately modelled on Sallman’s image.

One hundred percent of my sample recognized Jesus from a small, cropped version of Sallman’s Head of Christ.

I was able to find usable likenesses for all Skiena and Ward’s one hundred names with the exception of Muhammad (it being seen as blasphemous to represent him), King David, and several early Christian saints. These weren’t tested. The survey was multiple choice, so the correct answer was in the list to jog verbal memory. Each question had five options plus “don’t know.”

Excluding recent US presidents, there are five historic figures that effectively everyone in the United States recognizes: Jesus, Hitler, Abraham Lincoln, Albert Einstein, and George Washington. The group of widely recognized figures was dominated by heads of state and included three authors (Shakespeare, Mark Twain, and Edgar Allan Poe), two scientists (Einstein and Newton), and scientiststatesman-polymath Benjamin Franklin.

Recognizability is not just a matter of historical importance. Unusual faces help. Henry VIII looks well fed, Abe Lincoln is gaunt, and Hitler has that creepy moustache. In contrast, Thomas Jefferson gets lost in a bewigged crowd of America’s founders. Barely fifty percent could identify Jefferson from a picture, despite the fact that his face has been on the American nickel since 1938.

Of the hundred people on Skiena and Ward’s list, only thirty-one were recognized by more than fifty percent of participants (though the error bars of a dozen or so straddled that threshold). I believe that understates the total number of widely recognizable historical figures, though not by very much.

Here’s why. The Skiena–Ward one hundred is a ranked list. The last ten of the hundred are:

91. Pope John Paul II

92. René Descartes

93. Nikola Tesla

94. Harry S. Truman

95. Joan of Arc

96. Dante Alighieri

97. Otto von Bismarck

98. Grover Cleveland

99. John Calvin

100. John Locke

You don’t need me to tell you that the only person here whom most average Americans might recognize from a picture is Harry S. Truman (and only fifty-eight percent of my sample did).

The first half of Skiena and Ward’s hundred included twenty-three people whom more than half my sample could recognize. The second half (numbers 51–100) included only eight. If we assume that the above rate of decrease is typical, then you’d expect the third fifty (numbers 101–150) of a hypothetical extended list to have around three recognizable faces and the fifty after that (numbers 151–200) to have maybe one. Model this as a converging series, and the total number of all historical figures recognized by more than half the public would be about thirty-five.

The Skiena–Ward list includes recent presidents. As Roediger’s research shows, their fame is likely to be fleeting. It is surely a temporary anomaly, in the grand scheme of things, that Gerald Ford’s face is about as recognized as Shakespeare’s or Napoleon’s.

I adopted this admittedly arbitrary definition: a historical figure is someone whose main achievement occurred at least fifty years earlier than the time of the survey. That means we drop Nixon, Reagan, and George W. Bush as being too recent. I was able to find just four additional faces not on the Skiena–Ward list that most people recognized: those of Walt Disney, Dwight Eisenhower, Andy Warhol, and Lyndon Johnson (who barely makes the fifty-year cutoff). That comes to about thirty-two figures. There are fewer widely recognized faces from ancient and modern world history than there are US presidents.

The US public’s visual history is undeniably a distorted map. Fifty-eight percent of the recognized faces are those of white American men. There is only one woman on the list (Elizabeth I) and one who is non-white (Gandhi). No one ever said history was politically correct.

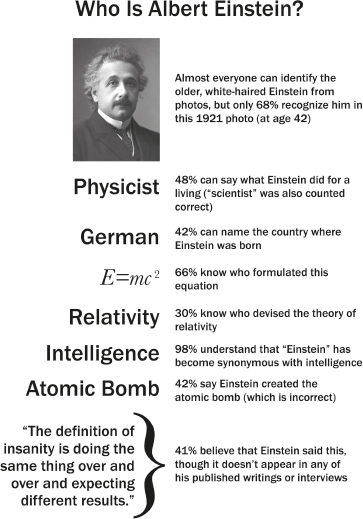

Misquoting Einstein

Surveys gauge historical knowledge narrowly—how many people can recognize a face, know a fact, think of an event. Connections between facts are as important—maybe more so. This book began with the tale of an educated woman who knew of Shakespeare and of Hamlet, just not the connection between them. That kind of fragmented knowledge is universal.

One survey of undergraduates found that only thirty percent could name the man who proposed the theory of relativity. The students surely knew the name Albert Einstein and the face. But the question didn’t ask about Einstein. It asked about the theory of relativity.

Like every other figure of history, Albert Einstein exists as a free-floating cloud of ideas, associations, and catchphrases not always tethered to a name or face. Not only are great people and events progressively forgotten, they are also progressively simplified. In life Einstein was a complex and multidimensional figure. He was a failure who couldn’t get an academic job and worked in the Swiss patent office, a Jew who escaped the Third Reich, an American celebrity, a civil-rights activist who called racism “a disease of white people.” Gradually Einstein’s narrative has been simplified and oversimplified. Ambiguity gets left on history’s cutting-room floor.

In one memory experiment, Roediger and his colleagues asked people of various ages to list events that occurred during the Civil War, World War II, and the Iraq War. There was much more agreement about what happened during the Civil War than during the Iraq War. Those who lived through a war had personal and idiosyncratic memories of it. Those who learned about a war purely from school and the ambient culture had more consistent interpretations.

Thus the past devolves from complicated reality to “history for dummies.” Along the way, the story gets garbled. I asked survey participants to identify the author of the following statement:

The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.

The epigram is widely attributed to Einstein on Internet quote mills, and politicians love to cite it. (Mis)quoting Einstein remains one of the cheapest brands of instant gravitas. But the insanity quote isn’t in any of Einstein’s published writings or interviews. It appears to have originated decades after the physicist’s death. With slight variations the quote surfaces in two rather different books published in 1983, the basic text of Narcotics Anonymous (not attributed to Einstein, who was never in rehab) and Rita Mae Brown’s Sudden Death,a roman-à-clef about the women’s tennis circuit (where it’s credited to a fictional character who is female and not a physicist). This is an example of “Churchillian drift,” whereby apt quotations by the marginally famous get attributed to someone more famous (such as Winston Churchill). The phenomenon is older than the Internet, but the profusion of poorly vetted quote sites has enabled it.

Another popular error is confusion about E=mc2 and the atomic bomb. The July 1, 1946 cover of Time magazine depicted Einstein with a mushroom cloud in the background. Inscribed on the cloud was E=mc2. Ever since then Americans have assumed that the iconic equation was somehow central to the bomb. It’s true that E=mc2 was Einstein’s equation and that Einstein co-authored the 1939 letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning him that Germany might build an atomic bomb. But the bomb had nothing to do with relativity and could have been made without Einstein’s theory. It was certainly made without Einstein, a pacifist who didn’t have security clearance.

I asked a survey sample to identify “the father of the atomic bomb.” That vague phrase is applied to several physicists—though never, by the well informed, to Einstein. Einstein was nevertheless the most common response (forty-two percent), beating out J. Robert Oppenheimer (eight percent) and Edward Teller (three percent).

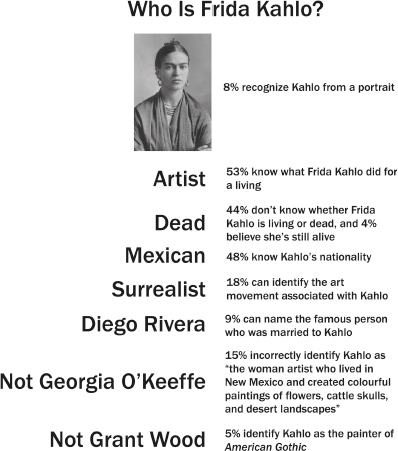

Frida Kahlo ranks high in popularity among twentieth-century artists. On closer inspection, public understanding of Kahlo’s life and achievement is incredibly threadbare. Scarcely half of Americans know that she was an artist or that she was Mexican. Few can connect her to surrealism, a famous self-portrait, or Diego Rivera. What is left of Kahlo if you don’t know anything important about her? It’s like the joke about Santa Claus being real—only he’s skinny, lives in Miami, and hates children.

Textbook Wars

In the summer of 2014, the College Board announced a new framework for Advanced Placement US history courses. Within days this normally boring development was in the news. The Republican National Committee called the framework a “radically revisionist view of American history that emphasizes negative aspects of our nation’s history while omitting or minimizing positive aspects.” The Texas Education Agency drew up plans to shun College Board materials in favour of Texas-sanctioned ones. Ken Mercer, who was behind the Texas proposal, explained: “I’ve had kids tell me when they get to college, their US History 101 is really I Hate America 101.”

By September of 2014, one Colorado school board had drawn up a policy limiting instruction to subjects promoting patriotism, the free-market system, and respect for authority. In 2015 an Oklahoma legislative committee formally banned the College Board’s US history framework, finding it lacking in the above values.

Why did a history syllabus hit a nerve? Stanley Kurtz, in the National Review, complained that the College Board was in thrall to historians who want “early American history to be less about the Pilgrims, Plymouth Colony, and John Winthrop’s ‘City on a Hill’ speech, and more about the role of the plantation economy and the slave trade in the rise of an intrinsically exploitative international capitalism.”

Kurtz (his surname is the same as that of the colonializing anti-hero of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness) identified a disconnect between parents and historians. Whereas most parents would be happy to have their children learn the same history they did, professional historians tend to be revisionists. They see their role as “revising” the existing understanding in the field. Textbooks gradually incorporate new scholarship, with the result that they change from generation to generation.

It all depends on perspective. A thirty-nation study of historical knowledge organized by James H. Liu, a psychologist at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, illustrates this problem perfectly. The study asked volunteers around the globe to identify the individuals who had most influenced world history, for good or for ill. For one nation, the ten most important figures in world history were:

1. Gandhi

2. Hitler

3. Osama bin Laden

4. Mother Teresa

5. Bhagat Singh

6. Shivaji Bhonsle

7. Einstein

8. Subhas C. Bose

9. Lincoln

10. George W. Bush

You can probably guess what nation was responsible for this list. If you’re not from that nation, you may have trouble guessing who numbers 5, 6, and 8 are.

The point is not that Indians have an exaggerated notion of their nation’s global importance. Every nation does. Another question in Liu’s survey asked participants to rate the relative importance of their nation in world history as a percentage, somewhere between 0 and 100 percent. Henry Roediger, who helped collect the US data, told me he “cringed” when he saw the estimates. Americans estimated that America was responsible for something like thirty percent of world history!

Roediger felt a little better when he learned that Canadian estimates of Canada’s importance were in the same range. In fact, around thirty percent turned out to be a typical answer in the nations surveyed (mostly large industrialized nations where Liu had colleagues). Add up all the averaged estimates, and they came to about 900 percent. Logically the figure shouldn’t exceed 100 percent, and realistically it should be less, for Liu surveyed only about thirty of the world’s 196 sovereign states.

Historians who choose to write textbooks understand that they have to sell to an assortment of finicky parents and school boards. For better or worse, history textbooks aim for a politically neutral and inoffensive style. The subtler issue is that historians make thousands of judgement calls about what to include, what to leave out, how much emphasis to give certain events, and what connections to draw. The cumulative effect of all these choices is to reflect the authors’ world views. Kurtz, and his liberal counterparts, aren’t being paranoid when they perceive cultural and political agendas in history curricula. The question is, what viewpoints are acceptable?

It would be possible to write a textbook presenting a positive (and factual) view of Adolf Hitler—they had them in Nazi Germany. It would be possible to write a Marxist, or libertarian, history that was scrupulously accurate and free of heavy-handed rhetoric. Most of us can agree that such histories would not be suitable as primary textbooks for teaching history in elementary and high schools. All we can rationally expect of our textbooks is that they embody the political and cultural values of the median citizen—and subtly, at that.

But this rational expectation is increasingly embattled. We live in an age of immersive narrowcasting. Partisan 24-7 TV networks react to news in real time and spill out onto social networks, becoming all-encompassing in ways that the yellow journals of old were not. Accustomed to such news sources, parents and politicians want history textbooks to narrowcast, too. The Fox News motto—“Fair and balanced”—captures this new sense of epistemological entitlement. We feel we are entitled not only to a history tailored to our politics but also to the belief that our history is uniquely objective and neutral—while all others are biased.

Dead White Males

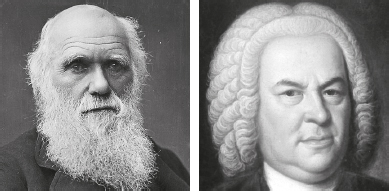

Americans are not that good at identifying the European males who fill the nation’s history textbooks. The two faces above are recognized by only about half the US public.

A multiple-choice survey gave these options for the bearded man at left: Charles Darwin; Alfred, Lord Tennyson; Karl Marx; Charles Dickens; and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Options for the gent at right were: Samuel Johnson, Marquis de Sade, Johann Sebastian Bach, Peter the Great, and Molière.

The correct answers are Darwin and Bach. It is of course true that their achievements have nothing to do with how they looked. Nevertheless we live in a visual society that is only getting more so. Textbooks, biographies, documentaries, and museum displays have pictures. That half the public doesn’t recognize Darwin or Bach implies that it hasn’t been much exposed to these figures.