Nineteen

The Fox and the Hedgehog

There is no first edition of the Greek poet Archilochus. His works survive only in fragments. A Greek sophist named Zenobius compiled a collection of proverbs containing this one from Archilochus: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Otherwise unexplained, this vaguely ominous line has haunted the Western imagination. In 1953, Oxford philosopher Isaiah Berlin gave it the standard modern gloss: a hedgehog is an expert who relates everything to a central big idea, while a fox is an eclectic, open to many approaches and comfortable with contradiction.

So defined, fox and hedgehog have become inescapable buzzwords. Nate Silver adopted a fox as the logo of his FiveThirtyEight blog. The title of a 2014 Wall Street Journal article framed the rivalry of two fast-food chains as “A Modern-Day Fox vs Hedgehog.” (“McDonald’s, the fox in this scenario, has been firing multiple shots in all directions to stay on top…Wendy’s…went full hedgehog—but instead of curling up into a spiky protective ball, it doubled down on its core burger line-up and introduced a very successful twist: the pretzel bun.”)

Just about everyone who makes the hedgehog-fox distinction does so in order to celebrate the virtues of being a fox. A fox is a generalist—open-minded, fact-based, and entrepreneurial. A hedgehog is committed to a “big idea” regardless of its relevance—the man with a hammer who sees every problem as a nail. Philip Tetlock, a psychologist at the Wharton School, is famed for tracking the fallibility of expert predictions. For the most part, think-tank experts (hedgehogs) barely beat tabloid psychics in accuracy. Tetlock found that credentialled experts were no better at forecasting than “journalists or attentive readers of the New York Times.”

This book’s results make a case for a kind of foxiness. Knowledge that is general, contextual, and even superficial appears to be useful in unexpected ways.

Gather several of the kind of general-knowledge questions you’d find in a trivia game and pose them in a survey. You’re likely to find that high scores correlate with high income, good health, and sometimes other positive attributes. It is probable that learning facts builds cognitive skills that cannot be acquired as readily in any other way (not even by learning “skills”). Breadth of knowledge can be useful in its own right. Our lives are a succession of small and medium-size decisions. A car owner weighs the need for a costly repair; a voter evaluates a campaign promise; a consumer decides whether to take a nutritional supplement advertised on TV. Most of these decisions will be made impulsively, with little or no research. There may not even be a conscious recognition that there is something to research. Those with broad knowledge are less likely to make horrifically bad decisions because they overlooked something and are more able to articulate what it is they don’t know.

Radon, Tiffany glass, urban homesteading, sous vide, annuity, checksum, bokeh, planned obsolescence, mise en scène…A person with broad knowledge has heard of these terms or most of them. The knowledge may be superficial—little more than the term and a vague sense of its context. But those who can put a word or phrase to a topic understand that there is a body of knowledge they lack. They can research it simply by typing the word into a browser. Those lacking the terms can’t. Broad knowledge, in your head, is the key to unlocking the cloud.

The “Ground Zero mosque” is a media coinage for Park51, an Islamic community centre planned for a site two blocks from the World Trade Center site. In its original conception it was to be a thirteen-storey tower designed by Lebanese-American architect Michel Abboud, a crystalline postmodern riff on traditional Islamic patterning. Dedicated to interfaith understanding, the building was to include a prayer space, a performing arts centre, sports facilities, a food court, and a memorial to 9/11 victims. In 2010, after preliminary plans were announced, a group calling itself Stop Islamization of America dubbed the project the “Ground Zero mosque”. Under that name it proved irresistible to the media, and it has been a topic of controversy ever since. The project has been downsized, assigned to a new architect, and reframed as an amenity of a luxury skyscraper. As of late 2015, only a relatively small Islamic centre has opened on the site. The centre’s very existence is held by some to be insensitive to the victims of 9/11. Stop Islamization of America is held by others to be a hate group.

I ran a survey of ten assorted questions about science, business, geography, history, literature, pop culture, and sports. None of the questions had anything to do with Islam or terrorism or Manhattan real estate. The survey also included opinion questions, one being this:

Park51, a planned Islamic center two blocks from the World Trade Center site, has been called the Ground Zero mosque. How do you feel about having an Islamic center so close to Ground Zero?

The fewer facts people knew, the more likely they were to object to the “Ground Zero mosque.”

There were significant correlations even with individual questions. Those who couldn’t say what nation America won its independence from were more likely to oppose the not-exactly-amosque. Ditto for those who didn’t know what DC Comics villain is the “clown prince of crime.” You might think that anyone who can’t answer these questions must be a sleeper-cell operative who failed the How to Pass as an American training course. But no: inability to answer these questions is a good predictor of Islam agita.

My “Ground Zero mosque” question has no right or wrong answer. It asks how you feel. But emotions and facts tie together. Many of those most opposed to Park51 appear to lack context. They have heard the Ground Zero mosque is a terrible thing—which is to say, they are blindly accepting someone else’s opinion. They may not know about the project’s planned memorial to the victims of terrorism or, for that matter, about the food court. There are about 2,100 mosques in America, 250 in New York State, and two in Lower Manhattan (not counting Park51, since it’s not a mosque). One of them (Masjid Manhattan) is six blocks from Ground Zero. It has been in operation since 1970. There had also been an Islamic prayer room on the seventeenth floor of the World Trade Center’s South Tower.

You don’t have to know any of the mosque statistics I just rattled off to deliberate. There are numerous mosques in New York City, and some must be fairly close to Ground Zero. Anybody want to bet there’s not a Ground Zero Starbucks? (Google Maps shows seven Starbucks outlets about as close to Ground Zero as the Park51 site.) Maybe the proper conclusion is that Manhattan has lots of buildings, and everything is close to something else.

Throughout this book’s research, I found correlations between knowledge and opinions on topical controversies. The well informed were more likely to have no problem with the Ground Zero mosque or genetically modified foods, to be sceptical of the need for a US–Mexico border fence and “trigger warnings.” These are hot-button issues to which culture warriors offer knee-jerk responses. Those with contextual knowledge are better able to think for themselves.

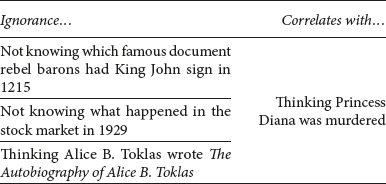

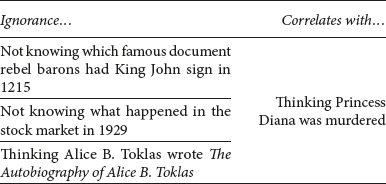

Many individual facts seemed to be predictors of opinion. I found, for instance, that among British subjects, many types of factual ignorance correlated with the belief that Princess Diana had been murdered. (Incidentally, it was Gertrude Stein who wrote The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.)

I also asked questions about behaviour, ranging from the mundane to the purely hypothetical. Should people be allowed to smoke in pubs? Would you throw your pet off a cliff for £1 million?

Here, too, those scoring well in general knowledge tended to claim more sensible, pragmatic, and socially responsible behaviour. One survey that had Britons name their Member of Parliament—many couldn’t, of course—also posed a contemporary ethical dilemma: “Suppose you run a small business that is getting unfairly negative reviews on social media. Is it proper for you to post favour-able reviews of your own business under a false name?” The people who didn’t know their MP were more likely to say it was OK to put up fake reviews.

In a US survey, those who said they’d vaccinate their children were more likely to know that humans didn’t coexist with dinosaurs, to be able to identify the Manhattan Project as the nation’s effort to build an atomic bomb, to know how many US senators there are, to understand that the United States is bigger though less populous than India, and to know that the War of 1812 came before the Civil War.

One hypothetical question was designed as a marshmallow test:

Suppose there was a high-efficiency light bulb that cost $100 but would save $300 in electricity costs over its ten-year lifetime. Would you be willing to buy it?

As written, this is a no-brainer. A $100 (£66) investment would not only help the melting ice caps but also save the user $30 (£20) a year. That’s the equivalent of a guaranteed tax-free thirty percent return on investment. The sensible answer is yes. The more knowledgeable people were about completely unrelated topics, the more likely they were to say they’d buy the light bulb.

Knowing which way to turn a screw to loosen it isn’t rocket science. Ninety-three percent got it right. It nevertheless correlated with buying the light bulb—and with childhood vaccination and with using reusable bags in the supermarket. There is much to be said for the ultimate contextual knowledge, which we describe imperfectly as “common sense.”

“Would you throw your pet off a cliff for £1 million?” Seven percent of the British public said they would. The percentage was double that for those who couldn’t name their MP or the earth’s largest ocean (in both cases, about fifteen percent said they’d toss their pet).

Another question asked,

Would you push a button that made you a billionaire but killed a random stranger? No one else would know you were responsible for the death, and you could not be charged with a crime.

Nearly one in five said they’d push that button. Those who scored low on a general-knowledge quiz were more likely to push the button, and yes answers were almost twice as common (thirty-six percent) among those who couldn’t name the year of the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks.

The foxlike philosophy of broad general knowledge is facing stiff headwinds. Our media zeitgeist favours a more hedgehog-like relation to facts. We are given digital tools that enable head-first dives into deep pools of interest while excluding everything else. The promise is that “everything else” will always be in the cloud, available on demand. Lost in this seductive pitch is that being well informed is about context as much as it is about factoids. It is the overview that permits the assessment of the particular, that offers all-important insight into what we don’t know.

A broad and lifelong education is not just a means to achieving wealth and health (though it has a lot to do with that). The act of learning shapes our intuitions and imaginations. Known facts are the shared points of reference that connect individuals, cultures, and ideologies. They are the basis of small talk, opinions, and dreams; they make us wiser as citizens and supply the underrated gift of humility—for only the knowledgeable can appreciate how much they don’t know.

The one thing you can’t Google is what you ought to be looking up.