CHAPTER 4

Stabilizing Russia’s Finances

”They are itching to get their hands on that money,” Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin told journalists in 2004, referring to the country’s spendthrift Duma members, its grasping industrial bosses, and the new class of security service elites who rose to power under Vladimir Putin. They wanted nothing more than to grab hold of the oil-fueled tax revenue that began flowing by the billions into Russian government coffers in the early 2000s. It was a rich prize for Russia’s ruling class, who wanted to spend the windfall on pet projects from roads to rockets to corruption-financed Rolls Royces.

But what would happen when oil prices fell, Finance Minister Kudrin asked them? It was only several years earlier that an oil price slump caused the deficit to explode in 1998, forcing the government to devalue the currency and to default on its debt. Oil prices were volatile, Kudrin reasoned, so Russia should save its budget surpluses to prepare for leaner times. “You can tell them until you’re blue in the face that you mustn’t spend it,” Kudrin moaned. “But even after I’ve explained all that, they still come after me, crying, ‘Hand over the money!’”1

The 2000s were boom years for Russia, as oil prices skyrocketed from less than $20 per barrel in 1998 to over $80 a decade later. Russia’s government raked in billions, especially as its new energy tax regime transferred an ever-greater share of oil company profits to the government. That Russia got rich as oil prices increased was foreseeable. More surprising is that not all its windfall energy wealth was spent immediately. Many oil-soaked dictatorships waste their petrodollars during good years and face dire consequences when prices plummet. Putin’s Russia had its fair share of excess, as the gaudy palaces of his friends and his security chiefs show. Yet what is more surprising is how much of the oil wealth Russia saved. Over the course of the 2000s, over half a trillion dollars was put in reserve funds, defended from the grasping hands of Duma deputies and KGB clans. Putin and his team had lived through the tumult of the 1991 and 1998 crises, and they knew that hard times would come again. They feared debt, made sure that the government lived within its means, and built up a large stock of financial firepower to deal with any contingency.

Putin’s government is often accurately described as including many former KGB colleagues and judo sparring partners. These groups have indeed acquired great influence. But they have coexisted, somewhat strangely, with a group of talented, technocratic managers centered in the Finance Ministry, the Economic Development Ministry, and the central bank. Putin selected many of these officials himself, and on issues that he cared about, such as budget deficits and inflation, Russia’s economic policy mostly followed their advice. The Duma continued to demand spending hikes and tax cuts; heads of state-run monopolies lobbied for higher subsidies; and Putin’s old judo-buddies accumulated vast commercial empires. But despite the push and pull of politics, and the near-constant demands for a couple billion rubles here or there, the Finance Ministry—backed by the president—won many of the battles that it fought. Its main goal was to avoid the deficits that drove Russia to ruin in the 1990s. With the president’s support, the government used a large share of its windfall tax revenue during the 2000s to pay down debt and to save for a future rainy day. By the middle of the decade, thanks to this fiscal balancing, Russia had the most stable financial environment it had ever known.

Paying Down Debt

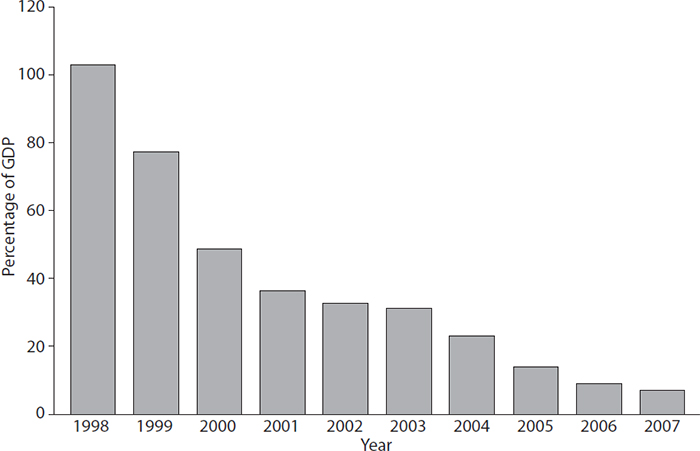

When Putin became president in 1999, Russia was over its head in debt. Moscow owed money to everyone: to international investors, who had lent Yeltsin’s government billions of dollars; to Russians themselves, many of whom held ruble-denominated bonds; to European governments such as France and Germany, who owned debts dating from the Soviet era; and to the IMF, to repay the bailouts of the 1990s. The dollar value of Russia’s total external public debt in 1999 was $148.5 billion. That was down slightly from the crisis year of 1998, when Russia owed $158.7 billion to external debt holders. But the 1999 figure was significantly higher than the $134 billion owned in 1997, the year when debt levels drove Russia to financial crisis. More daunting was the ratio of debt to GDP, which measures a country’s ability to pay its debts. In 1999 external debts were equal to Russia’s GDP. That was a dangerously high level for a country that had just emerged from a financial crisis.2

Yet repaying the many foreigners who had lent Russia money was not a major concern of most of Russia’s political elite. The Duma, which was responsible for approving government budgets, preferred to raise salaries and spending. During the early 2000s most Russians were still recovering from the 1998 inflation shock, and their incomes were still, in inflation-adjusted terms, lower than before the crisis. Boosting incomes was an understandable concern. Duma Banking Committee chairman Alexander Shokhin, for example, told the government in 2001 that if it wanted to make a $3.8 billion payment due to foreign governments that year, it should borrow money from Russia’s central bank rather than divert money from spending plans. Given that the central bank’s reserves were only $27 billion, and that such a proposal would reduce the reserves by over 10 percent, that was hardly a recipe for monetary stability.3 But it represented an understandable impulse to focus spending on Russia rather than its creditors.

Indeed, Shokhin was not alone in urging the government to prioritize current spending over debt repayment. The Communists in the Duma, who realized that the government’s decision to spend billions paying off foreign capitalists provided them with an easy political punching bag, jumped on the bandwagon. One Communist-backed petition declared that it was “immoral and unacceptable to pay billions of dollars to save the so-called positive international image . . . at the expense of our country’s future.”4 Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov attacked the government’s debt repayment proposals, arguing that the Kremlin was “continuing to crawl in the rut [dug] by Boris Yeltsin and his cronies.”5 Given how low an opinion most Russians had of Yeltsin’s financial management, this was stinging criticism. And $15.2 billion of the debt was due to the IMF—an institution that many Russians blamed for the country’s economic problems in the first place.6

Yet many Russian economists drew the opposite conclusion. The magnitude of Russia’s debt burden, they argued, was a main reason it should be paid down as soon as possible. Yevgeny Yasin and Yevgeny Gavrilenkov, two well-known economists, noted that “spending on the payment and servicing of foreign debt in 1999 will total (if there is no restructuring agreement) approximately 10 percent of GDP, which is comparable to the entire federal budget’s share of GDP, and about 30 percent of national savings.” That was a massive—and unsustainable—sum. If debt service of such magnitude persisted, it would hobble Russia’s economic prospects. Far better, they reasoned, to pay down the debt sooner rather than allow it to hang over the country’s economic prospects. “A long-term budget, in which a primary surplus of no less than 3–4 percent of GDP is envisioned,” is what Russia needs, they argued. “Such a budget would demonstrate the government’s firm intention to pay off its debts.”7

Despite public animosity toward foreign lenders and the IMF, Putin’s government sided with liberal economists and against the Communists. The Kremlin focused relentlessly on reducing its debt burden. Rapid economic growth helped, providing Russia with more resources—and more tax revenue. Russia’s GDP grew quickly during the early years of the decade, expanding by 9 percent in 2000 and 5.4 percent in 2001.8 The debt to GDP ratio fell sharply, from a dangerous level of 100 percent of GDP in 1999 to a manageable 23 percent of GDP just four years later.

Only part of the improvement was due to economic growth. The government also spent billions of dollars reducing its outstanding stock of debt. One reason it did so was that, in the early 2000s, the government faced a steep debt servicing schedule, with billions due each year. The repayments peaked at $17 billion in 2003, a date that motivated the government—and put pressure on the recalcitrant Duma to contain its spending plans and ensure that the government would not default.9

Putin’s economic team worked vigorously to drum up support for debt repayment. All the government’s main economic officials supported rapid debt repayment. This included not only Kudrin, the finance minister, but also Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov, whom Putin inherited from the Yeltsin era; German Gref, author of the economic reform program that kicked off Putin’s presidency; and Andrei Illarionov, Putin’s outspoken economic adviser.10 These officials used the 2003 peak of debt repayment—which they described as a “doomsday” event—to mobilize the political elite behind reforms to increase government revenue and thereby increase Russia’s ability to service the debt. Tax collection efforts, the centralization of revenue, and spending control were all justified by the need to pay off foreign debts and limit financial risk.11

Putin himself believed strongly in the need to wean Russia off debt, and he was convinced that the country backed this policy. Once Russia had passed the mountain of debt service due in 2003, Putin bragged, “We paid 17 billion dollars, and the country felt nothing.”12 At his annual dial-in press conference that year, the president underscored the tremendous reduction in the country’s debt burden and expansion of its reserves. “When I began working as president of the country, in 2000 the gold reserves of the Central Bank amounted to 11 billion dollars. That is, in ten years [since the Soviet collapse] the country saved $11 billion.” Now, though, the country was doing far better. “In 2003, in just one year it grew by $20 billion, and the reserves of the Central Bank are $70 billion.” Even as reserves grew, the president boasted, debt levels fell. “Today our ratio between foreign debt and GDP is better than in many Western European countries. And that is one of the most important indicators of the health of an economy.”13

FIGURE 4 Russian external sovereign debt as percentage of GDP, 1998–2007. International Monetary Fund.

After Russia met its mammoth $17 billion debt repayment in 2003, it was clear that the country had turned a corner from the 1998 default. The country’s economy had improved markedly, making a second default unlikely. In response to the improving economic circumstances, many leading economic officials sought to refocus attention away from debt repayment toward other pressing needs. As early as 2002, for example, Prime Minister Kasyanov proposed abandoning the budget surplus to cut taxes, something that the Finance Ministry vigorously opposed.14

Driven by Finance Minister Kudrin, the government remained focused on bringing down its debt burden, prioritizing debt repayment above nearly every other issue. In 2006, Moscow repaid the $21.3 billion it owed the Paris Club of foreign government creditors, handing over an additional $1 billion for the right to pay back the debt ahead of schedule.15 The debt burden shrank rapidly. Thanks to Russia’s budget surpluses, the government did not issue foreign currency debt again until 2010, when it raised $5.5 billion to lock in historically low interest rates. Investors lent to the Kremlin for a ten-year period for only 1.35 percentage points higher than what they charged the U.S. Treasury.16 The threat of a messy default—which hung over Russia for the first decade and a half of independence—was no more.

The Savings Funds Debate

As it paid down its debt, Russia soon faced a problem its leaders had never known: what to do with extra money. Having slashed spending and hiked taxes in the early 2000s, and continuing to benefit from high oil prices, the country had a budget surplus. If oil prices stayed at the same level, the budget would be in surplus far into the future. The natural response, many Russian politicians argued, was to spend the extra cash, either by cutting taxes or by increasing spending. After the tax reform of the early Putin years, including the introduction of a flat 13 percent income tax, Russia’s tax burden was relatively low, which removed the urgency of tax cuts. But government spending levels were far below those in similar countries, and the quality of health care, education, and infrastructure was mediocre. The case for increasing public investment in these spheres was easy to make.

But to the surprise of most observers—and in contrast to some of its commodity-dependent peers—Russia did not spend its entire oil windfall. During the early 2000s, it put much of the revenue from high oil prices in the bank, saving it for rainy days. The decision to save the budget surplus, first through a fund called the Stabilization Fund, then through the Reserve Fund and the National Welfare Fund, was one of the more controversial economic decisions of Putin’s presidency. Yet Putin repeatedly backed Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, who spearheaded the creation of these savings funds and defended them against demands that they be spent today rather than set aside for the future. Everyone in government had a pet project on which to use the savings—some on infrastructure, some on industry, some on tax cuts. But with Putin’s backing, Kudrin fended off most of these attempts to spend Russia’s savings. The result was that Russia entered the crises of 2008 and of 2014 with several hundred billion dollars of reserves, a serious cushion for hard times.

The idea of creating a stabilization fund began spreading around Russian economic policy circles immediately after the 1998 crash. Everyone realized that the budget’s heavy dependence on taxing the oil industry meant that revenue would rise and fall along with the oil price, a factor over which Russia had no control. Indeed, Putin’s effort to hike taxes on the oil sector exacerbated the dependence on oil revenues. Higher oil taxes were justified on the grounds that the oligarchs had won control over energy assets at unjustifiably low prices, and that taxing the energy sector would allow tax cuts for manufacturing and service sector firms. But the more revenue that came from oil, the more the government budget would fluctuate with world oil prices. No one had forgotten that the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union and the 1998 default both coincided with an oil price slump.

FIGURE 5 Oil prices, 1999–2007 (U.S. dollars/barrel). Brent crude, nominal terms. U.S. Energy Information Agency.

The only way Russia could extract sufficient tax resources from its energy sector while avoiding huge oil-price-driven fluctuations in government revenue was to save money when prices were high in order to spend when prices were low. That may sound easy, but the politics of public spending makes saving a budget surplus extraordinarily difficult. The U.S. budget, for example, has been in surplus only a handful of times over the past half century.17

The creation of a durable mechanism for saving Russia’s budget surplus, therefore, required a combination of factors. For one thing, the memory of the previous crashes was still fresh—and still painful. Everyone remembered the havoc that an unsustainable budget deficit could cause. At the same time, this memory was backed by ironclad political will to enforce discipline and to defend the savings from would-be raiders. The political decision to save a portion of Russia’s oil funds was enforced by the Finance Ministry—but this policy was only enforceable because everyone knew it was supported from the top.

The intellectual work behind the creation of a savings fund began as early as 2000, with several influential think tanks and research institutes publishing papers on the subject. A group of economists from Yegor Gaidar’s Institute of the Economy in Transition, for example, prepared a report in 2001 noting that “the average yearly price of oil . . . reached a fifteen- to twenty-year high in 2000.” High prices, this research suggested, would not last forever. When prices fell, if Russia was not prepared it would suffer a budgetary collapse, as had happened just three years earlier.

Countries such as Norway and Chile, however, had found savings funds to be a useful mechanism for managing commodity price volatility. Norway is a major oil and gas producer, while Chile is the world’s largest copper miner. Both countries were as dependent on commodity prices as was Russia, and both used savings funds to help balance their budget through boom and bust cycles on global commodity markets. Russia could learn from other countries’ use of such funds to smooth government spending over the course of boom-bust cycles, the economists reasoned, and thereby counteract the negative effects of commodity price slumps on the country’s budgetary position and the broader economy.18 Given the magnitude of Russia’s oil riches, global price trends would inevitably affect the country’s economy. A stabilization fund was a sensible means of managing the consequences.

Establishing a savings fund would require higher taxes on oil profits, something that Putin’s government was already working hard to accomplish. This move increased the budget’s dependence on oil taxes, a point that the government’s opponents often note. But the Kremlin had solid political and economic reasons to increase reliance on oil taxation and decrease the role played by other sources of revenue.

The Kremlin wanted to cut taxes on every sector of the economy, from industries to individuals, and hiking taxes on the oil sector would enable such a policy to be budget-neutral. There was a clear political logic at play. Low taxes were a crucial part of the social contract that Putin was forging. Political activism of the sort that had characterized the 1990s, whether by striking coal miners, industrial lobbies, or wily oligarchs, was strongly discouraged. The best way to keep people out of politics was to reduce their interest in government policy. If government took a big percentage of income and profits via taxes, people might start asking questions about how their money was spent. Far better to fund the government not on the backs of potentially rebellious citizens but on the oil companies that Putin’s government was bringing to heel.

But the most important rationale for cutting taxes on the nonoil sector was not politics but economics. As oil prices recovered from their late-1990s lows, Russian economists began to worry about “Dutch disease,” a malady named after the deterioration in Dutch industry that had followed the discovery of a large gas field in the country in 1959. Once the Netherlands started selling gas abroad, Dutch companies converted foreign earnings into currency that could be spent at home. This drove up the value of the Netherlands’ currency. A more expensive currency meant that other Dutch exports—manufactured goods, say—were less competitive on foreign markets than those of other countries. So the Netherlands manufacturing sector struggled even as the gas sector boomed.

Since the Netherlands’ experience with “Dutch disease” in the 1970s, economists have found that commodity windfalls harm other sectors of commodity-dependent economies. One way to counteract Dutch disease is to make nonoil sectors more competitive. In the early 2000s, fearing the emergence of Dutch disease, Russian economists advocated cutting taxes on the noncommodity portion of the economy, and making up the revenue by more heavily taxing the oil industry.19 This strategy fit with the Kremlin’s other goals, and the relative tax burden on industry and services fell over the early 2000s even as oil taxes increased.

Leading Russian officials made these arguments as they reshaped Russian tax and budget policy during the early and mid-2000s. Speaking to the Duma in 2001, Putin argued that “the federal budget should be protected to the highest possible degree from external influences such as a change in world prices for Russian exports.” Putin saw two means of doing this. One was to adopt a “conservative macroeconomic prognosis proceeding from a pessimistic appraisal of prices for Russian exports”—in other words, not overestimating future oil prices. A second technique was to set aside “additional revenues which arise under the condition of higher export prices,” and to save them in case oil prices fell.20

The latter idea pointed toward a stabilization fund. Kudrin and other budget hawks convinced the president that extra money should be placed in a special savings vehicle to guarantee it would not be spent. Support for a stabilization fund gathered steam. Putin himself repeatedly and publicly underscored the need for a stable budget over time. He regularly criticized Duma deputies who “vote for legislation that will ruin the budget.”21 And he declared that “stability of budgetary and tax policy is a very important factor of economic development. . . . Sound macroeconomic policy is needed.”22 With the president’s support, the Stabilization Fund was created on January 1, 2004. Revenue earned when oil exceeded a specified price was to be deposited into the fund and invested in high-quality dollar, euro, or British pound–denominated foreign government bonds.23 It was a cautious investment strategy designed to ensure that Russia’s savings were carefully managed.

The savings fund immediately faced a new challenge. By 2005, the second year of its existence, the fund had already surpassed its limit of 500 billion rubles. Oil taxes were gushing into government coffers, and the oil price kept rising. Russia’s government deposited in the fund one-third of the tax revenue it earned that year from taxing oil.24 Soon the fund was reaching its limit. Per the legislation that created the Stabilization Fund, any money in excess of 500 billion rubles could be spent on other purposes. The government decided to use the surplus to repay debt—a conservative choice. $3.3 billion was spent paying the IMF and $15 billion was set aside to pay off the Paris Club international creditors. Vnesheknombank, a state-owned bank, received $4.3 billion in debt repayments from the government, settling loans that had been made in 1998 and 1999. And $1.04 billion was set aside to close a deficit in Russia’s pension fund.25

In total $24.8 billion was withdrawn from the Stabilization Fund in 2005—but the fund ended the year with even more resources, $42.9 billion in total.26 All the investment choices so far were in line with the cautious fiscal policy. But if the fund remained capped at 500 billion rubles, the Finance Ministry would struggle to save the amount it thought necessary. After all, by the mid-2000s, Russia did not have much debt left to pay down. It would not be long, the ministry feared, before other officials would begin demanding spending hikes, thereby counteracting carefully laid plans to prepare for the next wave of low oil prices.

Putin, Monetarist

Felix Dzerzhinsky, the aristocrat-turned-Bolshevik revolutionary, is best known for founding the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. Like Stalin, Dzerzhinsky had considered becoming a priest before opting instead for a career that would earn him the nickname “Iron Felix” for his ideological devotion and for his brutality. Yet iron is not the only metal by which Dzerzhinsky should be remembered. Amid the hyperinflation that accompanied the founding of the Soviet state, Dzerzhinsky was a key supporter of the “gold ruble,” a new currency that finally stabilized the Soviet monetary system after the revolution. Dzerzhinsky was not only a ruthless secret police boss—he was a capable economic policy maker, too.27

Dzerzhinsky was not, it turns out, the only Soviet secret policeman to oppose inflation, or to focus on managing the money supply. Putin, too, made low inflation a key policy goal. The country had struggled with persistent inflation since the late 1980s. A small and stable amount of inflation, many economists believe, supports economic growth. But Russia’s experience showed why rapid price increases were so harmful. The inflation of the early 1990s sowed economic chaos, which fell most heavily on the poor. The late 1990s saw another rapid burst of inflation, with prices increasing by 85 percent in 1999 alone. But inflation fell sharply throughout the 2000s, reaching single digits by the middle of the decade.

FIGURE 6 Russian consumer price inflation, 1995–2005. World Bank.

The slowdown in price increases was surprising for several reasons. For one thing, Russia had long relied on inflation as a form of “tax.” The government could not raise sufficient revenue, so it filled the budget deficit by printing money. The subsequent increase in prices—inflation—reduced the real value of money held in bank accounts. This method of funding the government was far from ideal, but few analysts believed that Russia could collect sufficient taxes to balance the budget and reduce inflation. Second, the officials who ran the central bank during the late 1990s and early 2000s were the very same people who had presided over the inflationary surge of the early 1990s, and whose policies contributed to its prolongation. Most famously, Viktor Gerashchenko, who headed Russia’s central bank during the hyperinflationary years from 1992 to 1994, was reappointed to the position after the 1998 crisis. Based on his public statements there was little reason to think that Gerashchenko’s monetary policy beliefs had changed.

The most important reason to expect continuity was the strength of the proinflation lobby. Much of Russia’s manufacturing sector, for example, which inherited inefficient production practices and unnecessarily large workforces from the Soviet period, continued to teeter on the edge of bankruptcy. These businesses were kept alive throughout the 1990s thanks to cheap government loans. A policy of low interest rates helped these firms roll over debt, while inflation eroded the real value of the funds they were expected to pay back.

Russia’s influential export industries, including not only the oil and gas sector but also nickel, aluminum, and diamond mines, also supported loose monetary policy. They required large capital investments, so they benefited from cheaper borrowing costs. Nor did they suffer from the downsides of inflation. Because their commodities were sold abroad and priced in dollars, inflation did not devalue their revenue streams. But by driving down the real value of the ruble against the dollar, inflation made these exporters’ costs, such as workers’ salaries, relatively cheaper, thus boosting ruble profits. Indeed, export firms and the oligarchs who own them have been vocal backers of loose monetary policy, with some, such as aluminum magnate Oleg Deripaska, publicly declaring that the central bank’s management was “ridiculous.”28

Some Russian economists agreed with the critiques levied by the country’s business lobbies. These economists believed that an “excessive” focus on reducing inflation deterred economic growth. The government’s decision not to increase spending in line with oil price increases—a policy in part designed in order to avoid adding pressure to inflation—”causes underfunding of investments in infrastructure, high technology, and manufacturing,” complained one economist from Moscow State University. Rather than single-mindedly seeking to bring down inflation, this economist argued that “the main problem for Russia’s monetary policy is to find a way to exponentially increase budget and bank funding of socioeconomic and scientific-technical development.” Doing that required “goals, tools, and principles of monetary policy suited to Russian conditions”—not, he implied, monetary policy mindlessly imported from the West.29

Such economists argued not that inflation was good but that aggressively fighting it carried high costs. Viktor Polterovich, a well-known academic economist, penned a memo to the government titled “Reducing Inflation Should Not Be the Main Goal of Russia’s Economic policy.”30 The benefits of more expansive monetary policy would outweigh the downside of higher inflation. For example, such economists argued, the government and central bank could use a range of policy tools to cut the cost of lending. The central bank could reduce interest rates, expand the types of assets it accepted as collateral, and even provide unsecured loans to banks. These steps would free up room on banks’ balance sheets for further lending—and, these economists hoped, new investment. Similar policies might be used to encourage investment by state-owned firms. So long as the companies invested profitably, these economists argued, there was little to fear.31

These critiques of anti-inflationary policy, and support for subsidized lending rates, were supported by many Russian political elites. The most outspoken advocate of looser money was Sergey Glazyev, who served as a Communist member of the Duma in the early 2000s, before founding his own left-wing nationalist party, Rodina, in 2003. He ran for president on the Rodina ticket in 2004, promising to raise living standards and purge the oligarchs. His message performed far better than expected, before the Kremlin’s media machine moved to silence him. Since then, Glazyev has been coopted as an adviser to President Putin on questions of Eurasian integration. He was also reported to be in the running to be named head of the central bank in 2013, though he was not selected.32

If he had been appointed to the central bank role, it would have led to a very different monetary policy. Glazyev is a vocal opponent of the central bank’s tight money policy, which he has repeatedly criticized as “absurd.”33 The types of policies that Glazyev advocated—cutting interest rates, expanding the money supply, and restricting foreign banks in Russia—would have increased inflation, despite his claims to the contrary. But Glazyev’s main point was that Russia’s monetary policy was focused on the wrong goal. Price stability had displaced issues that Glazyev thought were more important, namely employment and economic growth.34

The liberal economists around Putin had little time for arguments such as Glazyev’s. They attacked inflation aggressively. For one thing, Putin himself backed a policy of low inflation and advocated an inflation target of 3 percent per year, a level far lower than independent Russia had ever experienced—and a goal it has not yet met.35 With such strong political support, the advocates of low inflation won most of the battles they fought. The appointment of Sergey Ignatiev as head of the central bank in March 2002, where he replaced the old-school Viktor Gerashchenko, was a key step in the solidification of Putin-era monetary policy. Under Ignatiev, the central bank’s decisions on regulation and interest rates rarely diverged from what was recommended by the IMF.

Across the economic ministries, most officials believed in keeping inflation low. Without stable prices, they argued, neither Russians nor foreigners would feel confident investing. The combination of capital flight, high borrowing costs, and shallow financial markets had plagued Russian business since the early 1990s, making it difficult to raise capital needed to build factories or expand product lines. Inflation exacerbated all of these problems, the government’s financial officials argued. The threat of higher inflation made Russians feel more comfortable saving in dollars rather than rubles, so Russia’s rich shipped their money abroad. Russian banks had to charge high interest rates on loans to offset the erosion of the funds’ value by inflation. Until inflation stabilized, these officals argued, Russia was unlikely to receive the investment it needed.

Putin’s economic advisers believed that loose monetary policy triggered inflation and reduced rather than increased investment. The threat of higher inflation would scare away potential lenders and diminish the supply of loanable funds, thereby driving up borrowing costs. Nor was it wise, Putin’s advisers argued, to rely on the government to lend to firms if the private sector would not. Russia’s state apparatus did not have a strong track record of investment success, they pointed out, but it did have a history, during the early 1990s, of sparking hyperinflation while supporting industrial investment.36

One means of reducing inflation was tight monetary policy and relatively high interest rates. This was the policy that Russia’s central bank followed under Sergey Ignatiev, its newly appointed chief. Yet many ministers and advisers also thought that such a policy was insufficient, particularly given the scale of petrodollars flooding into the country. The reality, many of Putin’s advisers argued, was that unless a significant portion of the country’s petrodollars was invested in foreign currencies, Russia could not reduce inflation. Andrei Illarionov, Putin’s personal economic adviser, advocated saving additional funds outside of Russia lest they add to inflation.37 Alexey Ulyukaev, the deputy chairman of the central bank, meanwhile, voiced fears that Russia’s economy was overheating due to oil-funded inflows.38

The key figure in the anti-inflation fight—as in the battle over Russia’s Stabilization Fund—was Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin. He was a committed inflation hawk, convinced that price increases threatened Russia’s economic future. “As inflation increases,” he wrote in one article, “so does its volatility,” so businesses struggle to make plans and lack the confidence to invest. Inflation also depressed asset prices, since potential investors faced uncertainty about their valuation relative to dollars.39 Because of this, Kudrin believed, as inflation increases, so does the volatility of economic growth.40 Hence restraining price increases was crucial to the government’s broader effort to foster economic development.

How could inflation be tackled? By carefully restraining the money supply, Kudrin argued. “Not achieving inflation goals is a sign of the state’s inability to control the money supply,” he wrote.41 “In countries with a high inflation rate,” he argued, “the rate of inflation becomes directly proportional to money supply growth, with a correlation coefficient approaching 1.”42 If the supply of rubles was reduced, Kudrin believed, price increases would slow accordingly. How, then, to control the money supply? They key was “vesting the central bank with operational independence on the one hand, and with a high degree of responsibility for achieving the set targets, on the other.”43 Such a policy would empower the bank to make unpopular but necessary decisions with regard to interest rates or banking regulation—choices that were needed if money supply growth was not to outstrip economic growth, threatening inflation.

Thanks to Kudrin’s influence and to the political elite’s openness to a low-inflation policy, price increases slowed during the 2000s. Inflation dipped below double-digit rates for the first time in 2006, a development Kudrin applauded.44 But he continued to worry that Russia’s oil riches threatened financial stability. He advocated using the Stabilization Fund to hold Russia’s oil profits in foreign-currency-denominated assets outside of Russia, a move he hoped would limit the inflationary effect of huge inflows.45

Absent a significant increase in the Russian economy’s productive capacity, distributing oil funds through higher pensions or subsidies would cause the economy to overheat, sparking inflation.46 “You see,” he explained in 2004, “every ruble in the economy circulates several times and drives up prices. Let’s say we inject money from the Stabilization Fund into a factory. If that money is not to have an inflationary effect, the factory must generate four times the investment. But our economy is not capable of doing that. That’s the arithmetic.”47

Saving the Surplus

Even after Russia paid down most of its foreign debt, officials in the Finance Ministry continued to vigorously defend the budget surplus provided by high oil prices. They continued to fear that high oil prices would not last. They also feared that letting oil profits flow back into Russia would expand the money supply without leading to an increase in productive investment, thereby causing higher inflation. Yet as Russia’s fiscal situation improved—and as oil prices continued to stay at relatively high levels—it became increasingly difficult for Finance Ministry officials to fend off attempts to spend Russia’s oil riches.

FIGURE 7 Actual oil prices vs. prices forecast in government budgets, 2000–2008 (U.S. dollars/barrel). Vatansever, The Political Economy of Allocation of Natural Resource Rents, 350; media sources.

One technique the Finance Ministry used to prevent spending hikes was to deliberately underestimate the oil price when writing annual budgets. Because the oil price was also the key driver of GDP and tax revenue, underestimating the oil price in budget projections made it seem as if the government would have less money than it did. Throughout the 2000s, with only two exceptions, budget projections underestimated oil prices, often significantly so. But tricks such as these were at best a short-term solution. Kudrin, who served as finance minister until 2011, wanted an ironclad method of defending Russia’s oil-backed budget surpluses, and to put away the excess funds as savings for a rainy day.

The policy of saving several percent of GDP per year remained controversial, both because many in Russia’s political elite believed the money could be better invested at home, and because many of them wanted to get their hands on it themselves. Sergey Glazyev, the one-time presidential candidate, remained a leading critic of Kudrin’s savings policy. Throughout the mid-2000s, he repeatedly took to the media to lambast the Stabilization Fund for failing to invest in Russia’s economy and saving money in foreign currency instead. “Instead of using the taxpayers’ money for the purposes of the socio-economic development of the country,” Glazyev publicly complained in 2006, the government “freezes funds in the Stabilization Fund and exports them abroad.”48

Kudrin’s goal was to protect the budget’s finances over the long run. Glazyev, by contrast, wanted to develop the country’s economy in the short run. “We have two to three years to put the country on a modern, innovative path of development,” Glazyev argued in 2006. The only way to accomplish his goal in such a short time horizon was to boost investment, by “radically changing the structure of the budget in favor of science and education, to transform the Stabilization Fund into a development budget, to create a system for long-term financing of productive investment.”49 Glazyev called for doubling spending on science, tripling spending on education, and quadrupling spending on culture. If the government were to take such a step, there “would be no budget surplus and no Stabilization Fund,” Glazyev promised. He saw that as a positive facet of his plan.50

Glazyev was the most vocal opponent of the Stabilization Fund, but he was not alone. Opposition focused on two main downsides to the fund. One was that it failed to deal with Russia’s existing social problems, mediocre health system, embarrassingly low male life expectancy, underfunded education, and decaying infrastructure, especially outside of the major urban centers. For many Russians, especially those not living in Moscow, St. Petersburg, or other large cities, the consumer boom of the mid-2000s seemed like a distant dream. Yes, living standards were rising, especially when compared with those of the late-1990s. But in agricultural regions and in industrial towns, life for many seemed at least as hard as during the Soviet period, when communism guaranteed jobs, housing, and cheap food. For these Russians, one academic noted, the government’s effort to save for a rainy day is “pointless, because the rainy day has already arrived! Russia’s social and economic problems have to be tackled now, and not bequeathed to future generations.”51

Yet Russia during the 2000s mostly ignored its working class, for reasons that will be discussed below. Despite the presence in the Duma of two nominally center-left parties—one of which was the Communists—Russia’s poor received relatively little attention from political leaders, who correctly foresaw that given rising wages and pensions, the lower class would remain politically quiescent. The main criticism of the Stabilization Fund and budget surpluses that Kudrin and the Finance Ministry carefully guarded came not, therefore, from the socially minded Left but from Russian business.

Here, too, Glazyev was perhaps the most outspoken participant in this debate, articulating critiques designed both for the working class and for industrialists, the two groups he hoped to assemble in a political coalition to oppose Kudrin’s tight budgetary policy. The industrialists were less interested in Glazyev’s fiery speeches about social crisis than they were spurred to action by his prediction of a looming industrial collapse.

Russian industry had shrunk since 1991 as the factories of the Soviet-era rust belt were shut. Across the political spectrum, Russia’s elite realized that industrial revitalization required new investment. Indeed, those industries that did receive new investment, such as the country’s cement plants and steel mills, looked reasonably healthy by the 2000s. Yet Russia’s leaders did not agree on how to increase investment. Kudrin and his allies hoped that, given an environment of economic growth, a stable currency, and low inflation, businesses would find it profitable to invest, and funds would naturally flow into Russian industries. To some extent this happened. Yet many others—and not only on the Glazyev-style left—thought that the government should do more to make funds available for investment. If the supply of potentially loanable funds increased, many people reasoned, the cost of borrowing would fall, and it would be easier to invest.

Where to find a large pot of funds to invest? Many Russians looked to the Stabilization Fund. In Moscow’s financial community, for example, proposals circulated for mobilizing the government’s savings and investing them in the real economy. One challenge would be ensuring that such funds were invested efficiently. Governments in general have a mixed track record of picking investments, and Russia’s recent experience was worse than average. Over the past half century, the Kremlin had plowed billions into enterprises with declining returns.

Moscow’s financiers proposed various methods of ensuring that investments were carefully targeted. If a portion of the Stabilization Fund was used to create retirement savings accounts for individuals, for example, Russians could make their own investment choices, placing the money in stock or bond funds. Such a proposal would give individuals a strong incentive to invest intelligently, increasing the funds available for firms looking to raise money. This proposal had the added benefit of filling an expected shortfall in Russia’s pension system.52

But Kudrin and his allies were unimpressed by such proposals. For one thing, many Russians had had negative experiences with investment funds thanks to a series of well-known frauds in the early 1990s such as the MMM pyramid scheme. For another, as in most countries, pension changes are politically toxic. A scheme to supplement pensions with private investments could prove politically disastrous. Most of all, however, proponents of the Stabilization Fund feared that funds earmarked toward investment would be misused and contribute nothing to economic growth. Glazyev’s rhetoric, for example, did little to inspire confidence. In his framing of the problem, the only problem was investment. He never addressed how to ensure that investment flowed to profitable projects rather than white elephants. Without effective investment mechanisms in place, Kudrin and his allies feared, what Glazyev described as “investment” could easily turn out to be waste. But Glazyev either saw no need for concern or believed that time was too short to bother with efficiency. Russia had to act immediately if it was to prevent “the degradation of Russia’s research and production” potential, he argued. Soon, the decline would be “irreversible,” the economic crisis “final.”53 But it was Glazyev’s proposed policy of investing without concern for efficiency, liberal economists noted, that had driven Soviet industry into the ground in the first place.

Kudrin and his allies struggled to resist demands for more spending. Russia’s economy and its government budget depended heavily on oil prices, and a sharp decline in prices would cause a gaping budget deficit. Taxes on hydrocarbons “provided 30 percent of all revenues,” Kudrin noted, with the federal government reliant on the two main levies on oil for 40 percent of its revenue in 2005. The creation of the Stabilization Fund had helped limit the risk of a price shock, but only to a point. Kudrin argued that in 2004 and 2005, only half of the revenue earned from above-average oil prices were deposited in the Stabilization Fund. The rest was spent.54

This had predictably negative consequences, Kudrin believed, the same consequences he foresaw when he initially advocated crafting a stabilization fund. For one thing, the influx of oil money drove up the real value of the ruble, making domestic production less competitive. By January 2005, Kudrin calculated, the real value of the ruble had almost reached its level before the 1998 financial crisis. The positive effects of devaluation on domestic production, therefore, were exhausted. “Further increases in the real effective exchange rate,” he predicted, “will have a serious negative influence on the competitiveness of the Russian economy.”55

At the same time, the decision not to set aside all the proceeds of above-average oil prices meant that the budget’s dependence on oil was increasing. “Stabilization will be effective if the creation of stabilization funds reduces the reliance of budget expenditures on the price of oil,” Kudrin argued in 2006, but the reverse was happening. To cut taxes on the rest of the economy, Russia had hiked taxes—and its dependence—on the oil sector. That was a sensible response to the challenge of Dutch disease, but Kudrin sensed risk.

He wanted Russia both to tax oil heavily and to spend as little of the revenue as possible. “Budget expenditures must rely on revenues that do not depend on temporary price surges,” he argued, pointing to oil’s volatility. “Countries that upon creating stabilization funds have taken the path of increasing budget expenditure, thereby violating the principle of limiting the money supply, have been unable to finance their growing budgetary obligation.”56 But having already cut taxes on nonoil sectors, if the government saved all its oil revenues, it would have little money to spend. Kudrin was open about what this meant for government spending: “Expenditure must also be reduced.” Kudrin and his allies in the Finance Ministry made this argument repeatedly, pointing to the disastrous deficits of the 1990s and to the unpredictability of oil prices. “International experience,” Kudrin argued, “shows that positive results in the economy have been achieved by countries that, besides creating [reserve] funds, have also constrained budget expenditure.” Russia should adopt a strict budget rule that capped spending increases at the growth rate of the nonoil economy.57 The only alternative, he believed, was “financial instability” when the next oil price shock arrived.

Yet Kudrin increasingly discovered that his calls for limiting spending fell on deaf ears. In the aftermath of the 1998 financial crash, Russians were poorer, but the memory of the crisis was fresh. So it proved possible to assemble a coalition in favor of limiting spending and building up reserves. In the early 2000s, this policy was backed by a wide range of Russian elites, from the business community to the head of the security services, because the stability of the state appeared to be at stake.58 The coalition that backed Putinomics understood the link between financial stability and political stability. By the end of the decade, however, after Russia had paid down its debts and stashed several hundred billion dollars in reserves, the need for ultraconservative budgetary policies was less clear.59 Many Russians had supported macroeconomic stabilization because they believed it was a necessary foundation for economic progress. Kudrin counseled continued caution. But many Russians believed that, because the country had sorted out its finances, it was time to reap the benefits of growth.