Don’t Be Difficult

Ask for what you want, push back on what you don’t, and beware the focus group.

Ask for what you want, push back on what you don’t, and beware the focus group.

Many folks would rather turn the other cheek than go against the grain, rub anyone the wrong way, or make waves. That’s understandable. It gets tiring being on the front lines of “Jesus fucking Christ!” all day long. Other folks put in half the effort—they get up on their high horse over some stuff, but when challenged, they crumple like an origami swan in a Jacuzzi.*

Those folks are not me. Perhaps they are not you, either.

If you’re like me, you know that being “difficult” means being confident and vocal, challenging ourselves and others, and standing up for what we believe in—even if that means taking an unpopular stance or one that puts us squarely in the crosshairs of “YOU again?”

It could be in the workplace—defending your unconventional ideas, high standards, or entrepreneurial spirit to less-than-like-minded colleagues.

It could be at home—when you decide this family needs to start eating healthy, goddammit, so you put Ben and Jerry on lockdown.

Or it could be on a lengthy FaceTime call with your mother during which you patiently explain that Aunt Cindy is no longer invited to your home because she’s a bitter old racist, and you don’t care if that makes it hard for Mom to decide where to spend Rosh Hashanah this year.

In any event, I feel like you and I have reached the point in our relationship where I can be blunt. So here goes: I am sick and fucking tired of people who don’t understand me telling me that I’m the one who’s difficult.

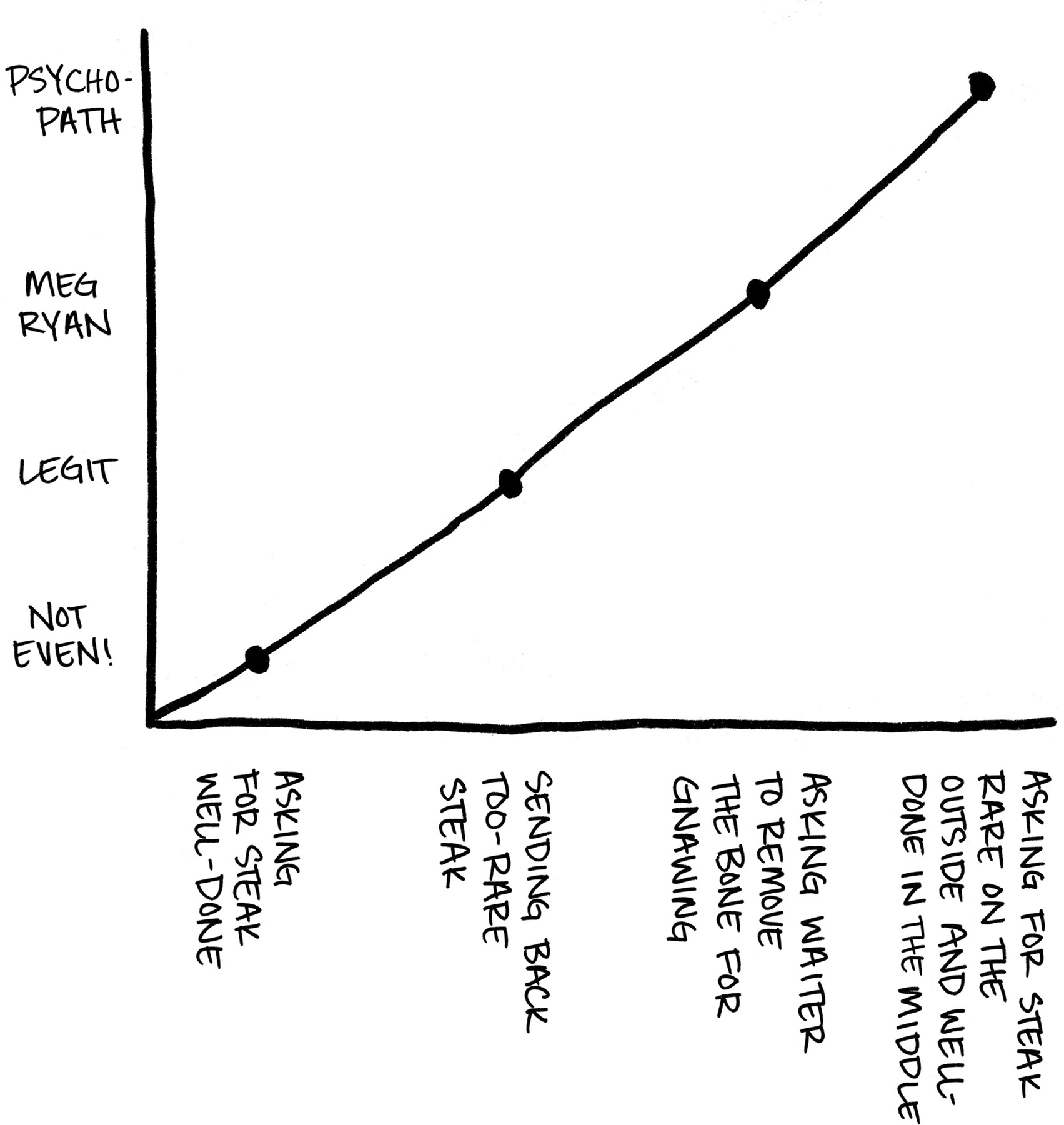

Whether it’s at work, in relationships, or at restaurants where I really meant it when I asked for that steak well done, why should I earn demerits—or nasty looks, eye rolls, melodramatic sighs, or spit in my condiments—for having a strong, clear, LEGITIMATE position and asserting it?

If this kind of stuff constitutes “being difficult,” then sign me up! (Though I would mentally redecorate that phrase to say “acting bullish in pursuit of things I want” and “holding others to the same standard I hold myself” as well as “remaining grossed out by undercooked meat.”)

Additionally, when challenged on such legitimate positions, I resent Judgy McJudgerson’s assessment that I’m the one who should soften, mellow, or completely blunt my edges to suit the narrow view of a vanilla majority; or that I should give up on my needs and desires so someone else—a classmate, a coworker, a line cook—can have an “easier” time of it.

What’s that, you say? Me too? Excellent. Let’s take that righteous indignation and run with it.

Being difficult: the spectrum

The difference between me and, say, the person who thinks I’m being difficult by sending back a too-rare steak that I ordered well done is that I understand that some other people like their meat bloody, and would therefore understand if those people sent back an overcooked filet and requested, you know, what they actually ordered. (I don’t make it a habit to send back food—I truly don’t—but this is an easy, universal example of what happens when you want what you want, you don’t get it, and unless you push back, your happiness is at steak. Er, stake.)

As for you? Well, Judgy might label you “difficult” for calling out your colleagues on bad behavior, or for speaking your mind at a PTA meeting. Maybe you’re guilty of defending a blue state opinion at a red state holiday party, or requesting a change to your friend Anne’s rehearsal dinner seating arrangement because you slept with her cousin five years ago after her graduation party and you’re gunning for a repeat. (She doesn’t know that, which is why she thinks you’re being “difficult,” not “a horndog.”)

Congratulations, you’re difficult! But legitimately so. (And in the case of Anne’s friend, you are also self-ISH, but we’ve been over that.)

There is nothing wrong with liking things the way you like them and asking for what you want.

There is also nothing wrong with aggressively pursuing what you want when it lies outside the bounds of what other people approve of or feel like dealing with. In fact, I think you should be commended for having the courage of your convictions, standing up for what’s right, and taking charge of your sex life. (Just wait until after Anne’s rehearsal dinner to seal the deal, ’kay?)

You’re even allowed to press your “difficult” agenda forward when it might seem ridiculous to everyone around you but in point of fact is hurting no one—per Meg-Ryan-as-Sally-Albright ordering pie à la mode.

Just don’t go around being difficult FOR THE HELL OF IT. Tormenting others as a form of pure entertainment is never okay. Put the lotion in the basket and walk away, Buffalo Bill.

How to be “difficult”

Now let’s say you have some “difficult” urges that you recognize but haven’t been acting on, because you’re a good little rule-follower whose ability to smile and nod in the face of other people’s bullshit would be legendary if they ever realized you were doing it. (Instead, they just think you’re “one of them.”) As a result, you’re not as deep into the spectrum as you’d like to be, and you’re wondering what you can do to get there.

Wonder no more.

Herewith, a primer on the twin pillars of being difficult: asking for what you want and pushing back on what you don’t.

You don’t get what you don’t ask for.

Requesting something different than what’s on offer is a perfectly reasonable thing to do. You probably shouldn’t go all Meg Ryan every time you go out to dinner (unless you really enjoy the flavor profile of someone else’s saliva added to your halibut), but you also don’t have to constantly settle for less than you want, need, or deserve in the course of an average day.

The worst thing that can happen when you ask for something is that the askee says no. And if they say no for a stupid reason, then you can and should ask again (see: I’ll be in my office). In Get Your Shit Together, I addressed this issue specifically as it relates to getting a raise or a promotion at work—literally asking your boss “What do I have to do to get you to give me what I want?”

Well, the same principle applies to getting anything your little heart desires or deserves. Just ask. For example:

Help around the apartment from your roommates. They seem to think it’s easier to live in filth than to wipe their Sriracha rings off the countertop once a week, but requesting a standard of communal living that surpasses “bus terminal Panda Express” doesn’t even make you difficult—it makes you an adult without a roach problem.

The best a hotel has to offer. Several hundred rooms at the same price do not equal several hundred rooms at the same experience. Why not ask for a southern exposure; a corner room with no neighbors; to be on the interior vs. street side; or to be closer to (or farther from) the elevator, whatever your preference? It takes five more minutes on the reservationist’s end to accommodate such requests, and it could mean a better view or night’s sleep for you, so why not? You may be difficult, but you’re also practical.

Good seats at the movie theater. There’s nothing I hate more than showing up late to the movies and getting stuck with shitty seats. This is why I refuse to meet certain friends outside the theater, because if they get hung up at work and I end up with a front-row, neck-craning spot for Tropic Thunder 2,* I will spend two hours getting progressively more angry, resentful, and cross-eyed. (This is also why some friends won’t agree to meet me outside the theater, because I insist on arriving forty-five minutes before previews. Suit yourselves, but at least we’ll still BE friends when the show’s over.)

A fresh personal pan pizza at the Domino’s in the Santo Domingo airport. Hey, the ones under the heat lamp looked like they’d been sitting there for hours. It’s not as though the gentleman behind the counter had anything better to do than make me a freshie, so I asked. (Actually, I made my husband ask, because his Spanish is better than mine.)*

Appointments at your convenience. Did you know you don’t have to take the first slot they offer if it doesn’t suit your preferences? Unless your acupuncturist is moving to Australia or your dentist is only open on Tuesdays and every other slot is taken, there’s no reason to settle for 8 a.m. (if you’re a later sleeper), noon (if you hate skipping lunch), or 5:30 (if you’re worried about getting stuck in rush hour traffic). The date and time the receptionist gives you is probably just the first one that comes up in the book. If you find yourself thinking I guess I could do that, but it’ll mean getting up ass-early/low blood sugar for lunch/road rage for dinner—DON’T SAY YES. Ask if they have anything else, or better yet, ask for a specific window, like only afternoons, or only Fridays. Does it create a little more work for the voice behind the phone? Sure, but the voice behind the phone gets paid for that.

Better, more consistent orgasms. Trust me, one “difficult” conversation with your partner about pacing and technique is worth far more than two in the bush.

What a bargain!

So now that you’ve asked for what you want—you difficult creature, you—it would behoove you to learn how to press for even more, and also how to push back on what you don’t want. That’s where negotiating comes in. This activity tends to brand those who engage in it as “difficult,” but if you don’t value your time, energy, and money, who will?

Whether we’re talking about your weeknight curfew, an extra personal day, or a better rate on a rental car, once you get an answer, it’s fine to ask whether the person on the other end can do better.

And remember that negotiating works both ways—not only in terms of what you’re getting, but of what you’re giving.If people are asking too much of you, sometimes you have to push back like a La-Z-Boy.

Below are some of my favorite tactics—ones that have gotten me everything from a better bottle of wine at the cheaper-bottle price, to a significant salary increase:

Ask the questions you’re not supposed to ask. The social contract helps prevent us from making one another uncomfortable, which is great if you want to enjoy a unisex spa without anyone staring pointedly at your naughty bits. But in a negotiation, it’s useful to make the other party flinch. For example, if you’re trying to get more money out of your employer (and you suspect your colleague Dennis makes a LOT more than you for the same job), ask your boss straight out how much Dennis takes home, and whether you’re worth less. You may get nowhere; you may get market information that’s useful when you look for your next job; or you may get an I like your style, accompanied by a nice bump in pay. That’s a lot of medium-bodied Oregon Pinot Noir.

Lay down the law. By trade, lawyers are tough negotiators, but you don’t need a JD degree to take advantage of one of their favorite strategies: asking for more than you know you’d settle for. If you do that, the person on the other side can give a little without feeling like he lost (or you can look reasonable for “agreeing” to less than you originally demanded). This works in all kinds of scenarios, including nonbusiness ones. Want your wife to go to that 49ers game with you on Thanksgiving? Ask for season tickets and negotiate down.

Establish the precedent: If you have a friend who asks a lot (read: too much) of you on a regular basis, you can reference the last thing she asked you to do with/for her when you respond to the next request. Something like, “Unfortunately since I left work early to go to your Pampered Chef party last week, I’m not going to be able to hit up your one-woman show at the Haha Hut on Tuesday.” It’s a little passive-aggressive, but so is Sheila.

Shock and awe: If your family thinks you’re difficult because you have an inflexible “traveling with children” policy, then you could propose a deal: instead of agreeing to go on a Disney cruise this year for her sixth, you’ll commit right now to taking your niece to Detroit to get her first tattoo when she turns sixteen. I bet you’ll get a counteroffer.

Take the shortcut: I may be a decent negotiator, but I also despise inefficiency. If I don’t have the time or desire to go back and forth on something, I just get comfortable with my own bottom line (and the fact that it might not get met), and then lay down an ultimatum, such as “I will pay [X amount] for the original codpiece worn by David Bowie in Labyrinth and not a penny more.” If it doesn’t work, then walk away, Renee. You might end up shelling out more than you technically had to, if you’d gone through a true negotiation, but you decided up front that a little more cash was worth a little less hassle. Sometimes, the person you’re really negotiating with is you.

Moral of the story: Don’t be shy about getting the best deal for yourself that you can. Heck, in many cultures, haggling is a way of life. Where I live in the Dominican Republic, if you don’t bargain down the original price quoted then you are definitely, certainly, surely, unquestionably being ripped off. Negotiating may not work at an establishment that has firm prices (or, in the case of my father, on the curfew front), but there’s wiggle room in a lot of life’s transactions.

Death by focus group

Now that I’ve helped cultivate your difficult streak, there’s a particularly lousy by-product of LCD Living that I want to draw your attention to. I call it “death by focus group,” and difficult people are the only ones who can prevent it.

As you probably know, the purpose of a focus group is to test a product or idea among a diverse group of consumers who have no skin in the game, in order to achieve a consensus about what works and what doesn’t before the professionals (who do have game-skin) can implement and widely roll out that product or idea.

For example, if Lululemon wanted to find out whether their customers would go for a line of Misty Copeland–inspired workout gear that featured itchy neon tutus, they could focus-group it. Lulu doesn’t want to spend millions on a product line that nobody likes or can do yoga in without looking like an idiot, so yeah, maybe do some market research.

(Also: use some common sense.)

Death by focus group (DBFG) happens when a smaller, not-very-diverse group of people get together to analyze something they actually have a stake in—such as a new company logo, rules for the condominium association, or where you should have your mom’s surprise seventieth-birthday party.

In these situations, and just like the random customers surveyed by Lululemon, the focus group participants each have their own valid opinions. But those opinions get complicated by one or more of the following:

Worrying about contradicting boss/coworkers

Worrying about contradicting boss/coworkers

Avoiding conflict

Avoiding conflict

Being the wrong demographic for the product/idea

Being the wrong demographic for the product/idea

Actually caring one way or another, i.e., having an agenda

Actually caring one way or another, i.e., having an agenda

Other miscellaneous baggage

Other miscellaneous baggage

At the end of this kind of informal focus group process, you typically end up with a “safe” result, in the sense that nobody hates it but nobody really loves it. Everyone knows there’s something that could be better, but no one has the courage or conviction to take a stand.

That is, unless somebody decides to get difficult.

Unfortunately, you can’t always escape the focus group, but at least you can breathe a little life into it—and simultaneously save everyone else from themselves. For example:

At work, don’t be afraid to make your voice heard when the group-approved logo looks like something your cat did in Photoshop.

At work, don’t be afraid to make your voice heard when the group-approved logo looks like something your cat did in Photoshop.

Among neighbors, don’t let a bunch of Lazy Larrys keep the whole building from staying up to code.

Among neighbors, don’t let a bunch of Lazy Larrys keep the whole building from staying up to code.

And if you’re Skyping with your siblings to plan your mom’s party, don’t be afraid to say, “Who needs another ‘festive brunch’ with mini-cupcakes and endive salad? Our mother deserves a trip to Vegas to see Magic Mike Live, and if you’re not willing to make it happen, I’ll book two tickets for her and me, and we’ll just see whose name figures prominently in the will.”

And if you’re Skyping with your siblings to plan your mom’s party, don’t be afraid to say, “Who needs another ‘festive brunch’ with mini-cupcakes and endive salad? Our mother deserves a trip to Vegas to see Magic Mike Live, and if you’re not willing to make it happen, I’ll book two tickets for her and me, and we’ll just see whose name figures prominently in the will.”

This crusade against DBFG may seem frivolous—especially when other gurus are out there curing cancer with plastic charm bracelets or whatever—but I have a clear objective in bolstering your defenses against this very real and present threat. Because mark my words: When the Zombie Apocalypse comes, focus group mentality will be the literal death of us all.

A taste test

Have you ever cried at work? I already told you about that time I cried in the town house when my boss yelled at me, but that was by no means the peak of my crying-at-work oeuvre. Oh, how I have wept in cubicles! I’ve sniffled and snuffled in ladies’ rooms. I’ve fought back tears in the doorway of many a boss, only to shed them, copiously, in the privacy of my own hard-won office.

A memorable sob session occurred a few years ago when my then-boss told me I had “difficult” taste.

Some context: For more than a decade, my job as an acquiring editor for major publishing houses was to discover writers and stories that were worth sharing and that were ALSO capable of finding a large enough audience to make money on behalf of the company. Something like a million books are published each year in the US alone, and I was responsible for finding and nurturing about ten of them. I enjoyed a more-than-respectable career in terms of sales and review coverage for my books—they were nominated for awards, optioned for film, and sold in dozens of countries.

But did they all make a profit? Hell no. THEY RARELY DO, SON.

The harsh reality is that most books fail. They fail to find a large enough audience. They fail to win acclaim or sometimes even passing mention. They fail to make money. It’s just the way the business works (or doesn’t work, as the case may be), and it’s something every editor knows and grapples with, year in and year out. We, and our peers in the sales and publicity and marketing departments, confront failure every day.

To top it off, most publishers are susceptible to the mind-set that “if X worked, then all books like X will always work,” and “if Y didn’t work, than nothing like Y will ever work.” So as soon as you go to market with one thing that doesn’t sell like you’d hoped, suddenly all of the similar stuff you have on the docket is subject to fatal second-guesswork.

(One time, the CEO of a major house declined to let me bid aggressively enough to win a future multimillion-copy bestseller because “Cat books don’t work.” Who wishes they’d been a little more open-minded meow?)

Anyway, in this particular conversation I had a few years ago with this particular boss, he reasoned that the books I gravitated toward—often about dark subjects like sexual violence or drug abuse, or featuring unsympathetic narrators—were too “difficult” to sell, and that I might want to change my approach to what I liked, in order to make life “easier” on myself and the colleagues charged with publicizing and marketing the stuff I brought in.

Well.

I’m a real pain in the ass, but I can take constructive criticism. (Eventually. Usually after I stew about it for half an hour.) What burned my biscuits about this little tête–à–tête was not my boss’s assessment of my taste. He wasn’t wrong that the books I liked most were harder to sell than, say, books about old white people, to old white people. Old white people are very easy targets.*

Nor was he being especially critical or threatening about it, just maddeningly matter-of-fact.

What made me go back to my office and cry was the implication that it was pointless to even try to stay true to myself. That, in one of the most creative industries in the world, I shouldn’t stray too far out of the box. That I should turn my back on what I liked and open my arms to whatever came easy.

Successful publishing boils down to finding and connecting with an audience. So it seemed to me that blaming the kinds of books that I liked and understood for the difficulties of the business as a whole was somewhat misguided. I mean, yes, we all have to worry about the bottom line—but was the solution really to cut out an entire audience altogether?

“Sorry, folks who like to read about dark, sinister, salacious, controversial subjects. You’ll have to spend your money somewhere else. We don’t serve your kind here.”

As you might imagine, the idea of sticking to “easier” subjects and “friendlier” voices that were “more palatable to the masses” made me die a little inside. After I self-administered some Visine and half a Xanax behind my closed office door, I decided I wasn’t willing to accept “difficult” for an answer. I knew there had to be enough people like me out there to do business with, so I dug in my heels and fought harder and smarter to find and connect with them.

In that way, my boss’s decree of difficulty was helpful. It lit a fire of Fuck it under me, to prove that I didn’t have to commit focus group seppuku to succeed.

I’m happy to say that after I left that job, three of the “difficult” projects I’d left behind became bestsellers, which is a good stat for our business. (It would be like batting.333 in the majors, so, better than Joe DiMaggio, but not quite Shoeless Joe.) I’m not saying those sales were my doing—I’m just the proud middlewoman between great books and satisfied readers. But ultimately my affinity for unsympathetic narrators and dark, twisted, gritty, and taboo subjects did connect with a big audience AND make oodles of money for my former company—which was always the objective—and I didn’t have to compromise my taste to get it done.

Being difficult, for the win!

(Oh, and to my delight, I also had a second chance to publish a bestselling cat book. Felines of New York. Check it out.)

God, why do you have to be so difficult?

I already told you: because it usually works out better for me. But you know what? Sometimes it’s difficult to be so difficult! Mostly because other people don’t appreciate all the good you’re doing for them. I do it anyway, because I think that when the going gets tough, having the courage of your convictions is admirable—especially when you have, like, sixteen better things to be doing than defending your needs, desires, and values to a bunch of people who don’t understand why you care so deeply about anything they do not care deeply about.

In that case, all you have to do is understand that they are impoverished by their own narrow-mindedness, and keep on doing your thing.

BOOM.