You Will Regret That

Says who?

Says who?

When I was a college English major we had something called the General Exam, a two-day, eight-hour test you’d take toward the end of your senior year, the scores on which would establish whether you graduated with honors and also what level of honors. Magna, summa, etc. All very important-sounding Latin shit.

Well, you might say I was “generally” aware of the existence of this exam, but not the exact dates on which it would be administered.

By the beginning of my second semester of senior year—January-ish, 2000—I was in love with a guy I had known for less than six months and I had approximately eleven dollars in my bank account after spending my fall term-time job wages on books, printer cartridges, Au Bon Pain asiago cheese bagels, and an amazing fluorescent red wig that I still own to this day.

I remember my mother coming to visit, and over lunch I told her about my new boyfriend and how I was trying to figure out a way to join him in New Orleans that spring for a music festival, but money was tight, yadda yadda. From her purse, she produced manna from heaven in the form of a belated birthday check from my grandmother.

Handing it to me, she asked if I would be using it to buy a plane ticket.

I couldn’t tell if she hoped I’d be able to fulfill my dream of gyrating to Lenny Kravitz and stuffing my face with shrimp po’boys alongside the man I was sure I would marry, or if she was testing me to see if I realized that I probably had more pressing expenses. In any case, I answered honestly (“YES!!!”) and booked myself a $200 nonrefundable flight to the Big Easy for the first weekend in May.

Sometime in March-ish, my friends started talking about “the Generals”—as though they were actively preparing for an upcoming test that had barely registered on my radar in almost four years of school. I really, truly, had not thought about it for a second. I can’t explain why or how I missed the memo, but I was shocked—SHOCKED, I tell you—to learn that this exam was due to take place the same weekend I was due to be knee-deep in daiquiris and crawdads. And probably some nookie.

Well, I thought, I can’t be in two places at once. And the plane ticket is nonrefundable. And I cannot afford to lose two hundred dollars to this mistake. Also I really want to go to Jazz Fest. Maybe there’s a makeup day for the test? Surely other people have conflicts or emergencies that would necessitate some sort of calendrical do-over?

I poked around on the English department website and didn’t find anything that would help me out of my predicament, so I called the person listed as my advisor (to whom I had never before spoken) and explained the situation—that I had foolishly booked air travel before I knew the dates of the exam, I couldn’t afford to void the tickets, I really wanted to go on this trip, and could I possibly take the test another time?

In a word: no. (Apparently these dates were made very clear to incoming seniors back in September, and maybe there was some kind of makeup day—my memory is hazy—but either way it was not available to me after I admitted exactly why I was going to need that do-over.)

“Okay,” I said. “So, um… what happens if I just don’t take it?”

“The trip?” said my advisor.

“No, the General Exam. What happens if I just don’t take it? Can I still graduate? Can I get honors?”

“Of course you can graduate,” she said, at this point sounding a bit peeved. “And yes, with honors from the university if your GPA allows it. But not with honors from the department.”

She explained that there would be no difference on my diploma either way, but if I wanted to apply to grad school, my score on the General and my standing in the department would matter.

“Oh.” (I was not planning to apply to grad school.) “Then I think I just won’t take it. There’s really no penalty?”

“Not technically, no. But do you really want to prioritize a pleasure trip over this test? I think you’re going to regret that.”

“Right! Well, thanks for your time. I’ll think about it and let you know.”

Two months later I was cavorting in New Orleans with my future husband, so I’d say it worked out pretty well, and that I have no regrets.

Except for that last daiquiri. Oof.

But it feels so right

In “You will change your mind,” we talked about what happens when people tell you that you’ll never do the thing you say you are GOING to do. Here, we move on to people telling you how you’re going to feel AFTER you’ve done it.

You want to be a sculptor?

You’ll regret that [when you’re dying, penniless and unappreciated].

You want to go vegan?

You’ll regret that [when people stop inviting you over for dinner].

You want to be single forever?

You’ll regret that [when you’re still swiping left and right at seventy-five].

Both attitudes are condescending, just in different ways. Yay! But the root cause is the same: You’re making choices other people either don’t agree with or don’t understand—i.e., what they think of as the WRONG choices, even if said choices are ABSOLUTELY RIGHT for you. Often, this means they’re imposing their own subjective opinions on you. (See: “You want to be a sculptor?”) It’s not fun, but you can learn to recognize and work around it, rather than be bullied into preemptive regret.

Still, it’s important to note the difference between OBJECTIVELY WRONG, as pertains to morals, ethics, and the law, and SUBJECTIVELY WRONG, as a matter of opinion.

Like, just because I’m all “You do you” doesn’t mean I condone being an asshole or a psychopath. (Or a ventriloquist—that shit is freaky.) If you make the OBJECTIVELY WRONG choice—hurting or exploiting another person, or breaking the law—you should absolutely be judged for it. In such cases, “wrong” is a fact, not an opinion. So if you’re catfishing sad, hairy dudes online or chucking your empty Sprite bottles in the park, cut it out.

(Littering is punishable by both fine and my undying scorn.)

Then there are choices that may not be illegal/immoral, but are still OBJECTIVELY WRONG. Such as making a wrong turn. Not a big deal, but you need to correct it—take three more rights and your next left and you should be fine. If you see your friend about to do something like this, you should probably warn them. If you see your enemy about to do it, you may wish to keep mum and enjoy knowing they added an unnecessary forty minutes to their trip. Use your judgment.

SUBJECTIVELY WRONG is more applicable to choices like, say, getting a neck tattoo. When it comes to warning a friend (or foe) against decisions like these, I think we should slow our collective roll. What good is it going to do? Anyone who is seriously contemplating a neck tattoo won’t be satisfied until they get one anyway, and if they DO wind up regretting it, they don’t need yet another permanent reminder in the form of your “I told you so.”

Finally, we have INNOCENT MISTAKES, which are a little from column A and a little from column B. Usually the person warning you against making such a choice is injecting their own opinion in the mix (see: neck tattoos), but also has good reason to believe the odds are not in your favor. It’s nice of them to warn you, but sometimes you have to take the fall in order to learn the lesson for yourself. I’m reminded of the time I thought it would be easy to slide down the banister at my grandparents’ house even though my grampa told me not to and I got stuck on the post at the end of the stairs and my grampa then had to rescue/discipline me.

He was right to have warned me. I was wrong about banisters. And physics.

In short: If someone tells you you’re about to do the “wrong” thing and that you “will regret it”—it’s useful to think about whether that’s an OBJECTIVE or SUBJECTIVE statement before you let their judgment stop you from sliding down the banister of life.

Actually I guess that’s a bad analogy. How about “before you let them stop you from making your own mistakes and/or living your life any way you damn well please.”

One wrong doesn’t make a regret

For the sake of argument, let’s say you did make a wrong decision, in the sense that whatever it was didn’t work out the way you’d hoped. That still doesn’t mean you’ll necessarily regret it. Regret is heavy, man. People write sonnets about regret.

Sure, if a former professional boxer currently suffering from concussion-related degenerative brain disease told me I would regret spending fifteen years getting the crap beaten out of me because of what it could do to my health, I would appreciate the heads-up and take it under solid advisement. And then if I did it anyway and eventually found myself suffering from concussion-related degenerative brain disease, I might conclude that I had made the wrong choice, and regret it.

Also the leftover Indian food thing.

But there’s a spacious middle ground here—including Oops, won’t do that again and Huh, guess that was a bust, oh well, moving on. Like, I wouldn’t say I “regret” putting sauerkraut on my hot dog one time in 2005, but it was definitely the wrong choice for me and now I know better.

You’ve got to make your own mistakes, and own the mistakes you make

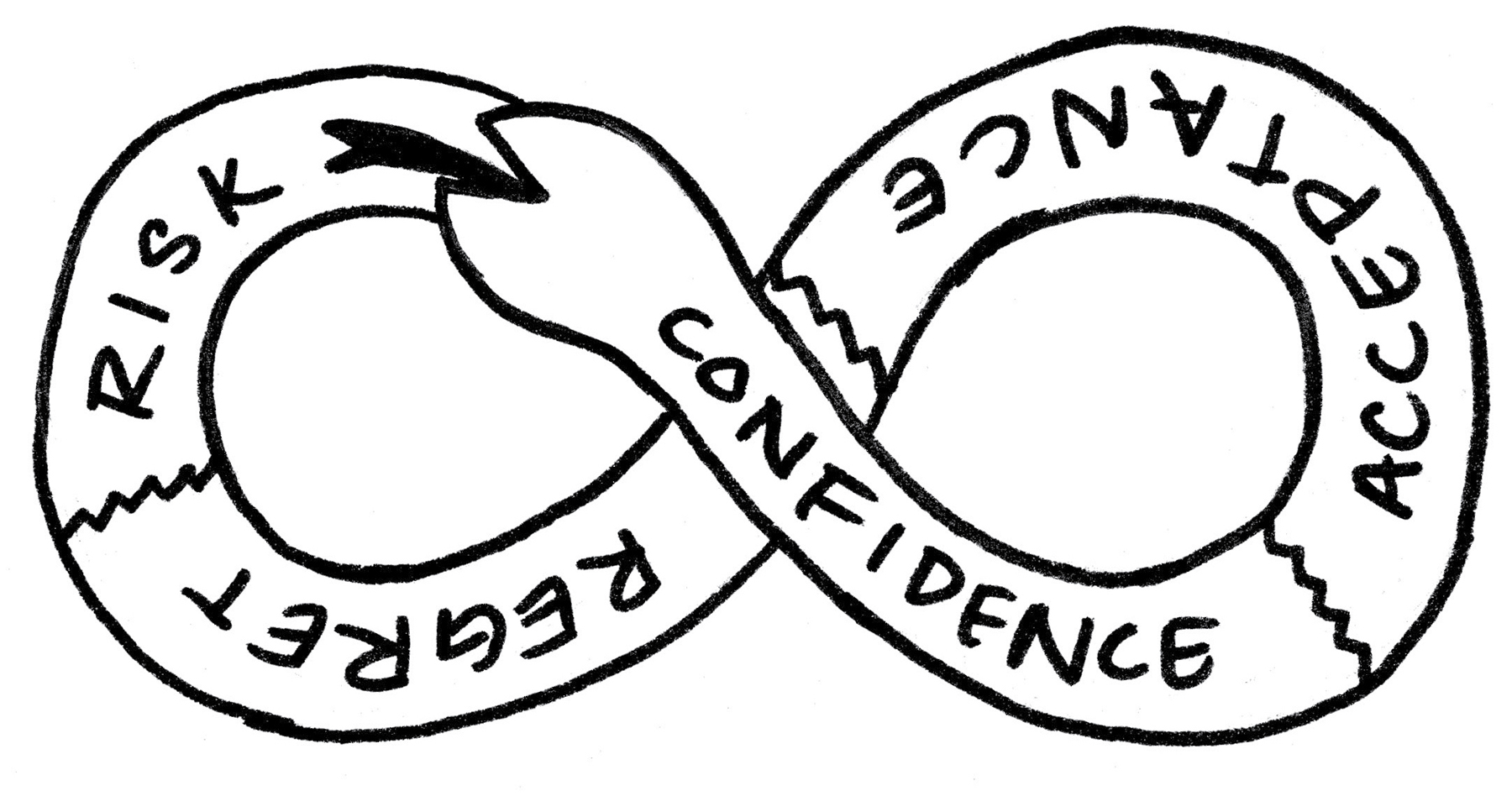

The other side of the “Accept yourself, then act with confidence” coin is “Act with confidence, then accept the consequences.”* In order to feel comfortable making decisions in the first place, you have to feel comfortable getting a few of them wrong. Because you WILL get a few of them wrong. And when you do, you can’t let yourself be permanently sidelined by regret.

More importantly, don’t let yourself be paralyzed by preemptive regret—foisted upon you by someone who fancies themselves a bit of a soothsayer but in reality, doesn’t have an experiential leg to stand on.*

Most of the time, you have to try things for yourself precisely in order to see if they turn out right. If not, you can recalibrate—which we also discussed in the final chapter of Part II, on taking risks. Remember that?

This book is a veritable Ouroboros of proof that “doing you” is mostly about “just doing it.”

You won’t know unless you have the confidence to take a risk and find out.

If you regret your decision, then accept the consequences, swallow the lesson, and start over.

With confidence.