One day in fourth grade, I (Howard) was happily entertaining myself with spit wads at the back of the classroom. Like many a child before me, I somehow believed that the teacher wouldn’t notice. But before too long she’d had enough. She took me to the old stucco wall at the back of the room. (I think the wall was originally white, but by the time my class came along, it was three shades of brown.) The teacher handed me a small pail of water and a rag and told me to clean the dirt-encrusted wall.

As an energetic fourth-grader looking for an outlet, I tackled the problem with both hands. An hour later I was still working diligently, all my attention focused on getting the dirt out of the crevices in that rough stucco.

“You know,” my teacher said casually, “if you work as hard at everything in life as you’re working on that wall, you’ll be a very successful man.”

She wasn’t trying to boost my morale with exaggerated praise or sugar-coating; she was making a simple, sincere statement of what she saw as fact. It was an act of genuine care, and I’ve remembered it my whole life.

We’ve all had experiences like that, where one heartfelt remark made all the difference. Sometimes such remarks come from people we respect and love, but not always. A considerate stranger may say something in passing that we think about for years. It’s not the words or the person who says them that makes such experiences memorable; we remember them because of the care.

We’re all accustomed to feeling a heightened sense of care for our loved ones. That’s one of the most rewarding things about our important relationships. But the idea of taking that generous, openhearted feeling into the street is something else entirely. Caring just for the sake of caring—that can be scary.

In the mean, cruel world, we have to keep our guard up, right? We can’t go around caring helter-skelter. A few nights of watching the news is enough to make anyone fearful and withdrawn. Before long, the paranoia shows up in slogans like “Look out for yourself!” and “Get them before they get you!”

Years ago, New York City was stereotyped as a place populated by residents who, even if the most hideous crime were being committed right in front of them, wouldn’t try to stop it. Many Americans believed that New Yorkers, living in an aggressive environment with a high crime rate, had become jaded and self-protective; they were perceived as people who thought that caring would only get them into deeper trouble, who didn’t want to “get involved.”

Even though statistics have since proven that New Yorkers aren’t as unwilling to lend a hand as they appeared to be from media reports, the loss of small, friendly communities has changed us all. We often don’t bother to meet our neighbors or even know who they are. Instead of acting on our natural instinct to care, we keep our guard up. We tell ourselves that if we don’t, people will take advantage of us. We worry that we’ll “waste” our energy on someone who won’t give us care in return. We believe that we can’t afford to care. But in fact the opposite is true: we can’t afford not to.

Care is a powerful motivator. It’s one of the most important core heart feelings. Care inspires and gently reassures us. Lending us a feeling of security and support, it reinforces our connection with others. Not only is it one of the best things we can do for our health, but it feels good—whether we’re giving or receiving it. Caring for someone or something has a regenerative, uplifting effect on us. The experience—a tangible one—goes directly to our hearts. And it’s an experience that we can pass on to someone else.

When we care for someone, we often express our feelings quite naturally through touch. We automatically hug our friends or pat them on the back. In conversation, we might touch their arm to emphasize a point or share a joke. When we’re introduced, even to a stranger, we shake the person’s hand—a moment of contact that makes a connection.

Researchers at the Institute have discovered that connection is more profound than we’d thought. If we touch someone, the electrical energy from our heart is transmitted to the other person’s brain, and vice versa. If we were to hook two people up to monitors while they connected, we’d be able to see the pattern of one person’s cardiac electrical signal (as graphed on an ECG) show up in the other person’s brain waves (as graphed on an EEG). [1,2]

To see what we mean, look at Figure 8.1. See how the heart’s signal in Person B is clearly reflected in the brain waves of Person A when the two research subjects are holding hands? Even when two subjects simply stand close together, without actually touching, we can detect a similar effect. [1,2] These results have been confirmed by other laboratories. [3]

FIGURE 8.1. Signal-averaging techniques were used to show that when two people touch, there’s a transfer of the electrical energy generated by one person’s heart (as represented by the tracings on an ECG) that can be detected in the other person’s brain waves (via EEG).

© copyright 1998 Institute of HeartMath Research Center

These intriguing results show that when we touch someone else, an exchange of electromagnetic energy—from heart to brain—takes place. Whether we realize it or not, then, our hearts not only affect our own experience, but they can also influence those around us. In turn, we can be influenced by the signals that others send out. We shift to resonate with their energy, as they do with us. We aren’t aware of this process, of course—at least not consciously. But it happens.

In Chapter 3 we learned that the frequency structure of the heart’s electromagnetic field changes dramatically in different emotional states. Frustration produces an incoherent signal, while appreciation creates a harmonious, coherent one. Core heart feelings—care among them—generate coherence in the heart’s field, while stressful feelings produce incoherence. [4] The resulting energy is transmitted throughout our bodies, and the fact that it radiates outside of the body as well has tremendous social implications.

Think about this. If those we touch or stand close to (say, in an elevator, a subway, or a department store) can pick up our heart’s electromagnetic signal in their brain waves, we’re in effect broadcasting our emotional states all the time (and receiving others’).

Of course, we communicate emotional states in other ways as well; we learn to read each other through a complicated set of cues. Our mood is often apparent from our body language alone. But even without body language and additional cues, we transmit a subtle signal. We can’t keep it in. All of us affect each other at the most basic electromagnetic level.

That means that the guy standing next to you in the checkout line may be more affected by how annoyed you are with your mother than either of you realize. And think of all the signals going back and forth in the crowds of people pushing their way into a rally or a rock concert. The implications are enormous.

We’re only just beginning to understand the complicated connections between people. But it’s already clear that if we touch someone while feeling an emotion like care, we’re potentially transmitting a signal to that person’s body that promotes well-being and health. [1]

Many doctors, nurses, and physical therapists are aware of the power of physical connection. There’s growing scientific evidence of the benefits of caring touch. [5] Touch therapy, or massage, is as important to infants and children as eating and sleeping are, according to Dr. Tiffany Field, director of the Touch Research Institute at the University of Miami School of Medicine. [6]

Clinical studies have found that touch triggers physiological changes. Touch has been proved to help asthmatic children improve breathing function, diabetic children comply with treatment, and sleepless babies fall asleep with less trouble. [7] Caring touch is also helpful for adults’ well-being and health. [8,9] In some cases, the effect is decisive.

In a recent issue of the scientific journal Subtle Energies, Drs. Judith Green and Robert Shellenberger tell of an elderly woman who was dying of heart failure. When her physician realized that there was no more he could do for her, he called her family in for a last good-bye. Remarkably, the moment the family members touched her, her heartbeat resumed its normal rhythm. Half an hour later, she was alert and sitting up in bed. [10]

While not everyone recovers from a caring touch, the heart and brain still receive the signal. There may be other explanations for this elderly woman’s recovery, and other contributing factors, but our studies on the electricity of touch have convinced us that the caring emotions of her family could have produced a discernible physiological effect—one powerful enough to encourage her heart.

Without care, life loses its luster. When people “just don’t care anymore,” we can see the lack of vitality on their faces and in the way they walk and hold their bodies. We can even hear it in their voices. Without the regenerative energy of care running through their system, their bodies have no motive for maintaining themselves—literally, no reason to live.

On the other hand, care produces equally visible effects on the body—a bounce in the step, a gleam in the eye, and an inordinate enjoyment of the fleeting moments in life. Health and vitality spring from heart-based emotions such as care. And even if the evidence weren’t so apparent, we could measure many of the physiological effects of care in the laboratory.

Even the experience of caring for an animal has been shown to improve morale and promote health in the elderly or those in nursing homes. Research supporting the health benefits of caring for pets ranges from the facilitation of social interaction to the physiological benefits of animals on cardiovascular responses. [11, 12]

Researchers at the Universities of Pennsylvania and Maryland found that a year after hospitalization for heart disease, the mortality rate of patients with pets was roughly one-third that of patients without pets. [13] Pets keep care an active part of millions of people’s lives.

They also help youngsters learn how to care. Studies show that children with pets have a higher degree of empathy. [14] However, it’s important to point out that the increased empathy is due not to the pet but to the sincere care that pets draw out. Pets are also a potential source of overcare and stress. It’s how people respond to a pet that determines the regenerative benefit (or lack thereof).

In the 1980s, David McClelland, a psychologist at Harvard, showed a group of subjects a video about Mother Teresa. As she moved among the poor and destitute, she was the embodiment of care and compassion.

To see if this vicarious experience would have an impact on his subjects, Dr. McClelland looked at their immune systems. We have an antibody called secretory IgA in our saliva and throughout our bodies. Our first line of defense against invading pathogens, it’s an important measurement of immune system health. After the group watched the moving video, test results showed an immediate rise in secretory IgA levels. In other words, the feeling of care and compassion evoked in them by the video had a measurable effect on their immune systems. [15]

Interested in finding out whether “self-induced care” would have the same effect as vicarious care, Rollin McCraty and his team at the Institute of HeartMath began by duplicating the McClelland study. They had very similar results. Immediately after watching the video, test subjects had an increase of 17 percent in IgA levels.

Then Rollin and his team took their research several steps further. They wanted to know whether feeling care without an external stimulus would have a greater or lesser effect. And what about other emotions? How would an experience of anger, for instance, compare to an experience of care? In addition, they were interested in finding out what the long-term effects of self-induced increases in IgA levels would be.

Test subjects were taught the FREEZE-FRAME technique and then asked to evoke a feeling of care and compassion for five minutes. Several days later, these same people were asked to feel five minutes of self-induced anger by remembering a situation or experience in their lives that had made them angry and recapturing the feeling as best they could. In both cases, IgA samples were taken immediately afterward and then every hour for six hours. Figure 8.2 illustrates the results.

After five minutes of feeling care and compassion, the subjects had an immediate 41 percent average increase in their IgA levels. After one hour, their IgA levels returned to normal, but then slowly increased over the next six hours. Rollin observed that self-induced care actually resulted in a larger rise in IgA than the vicarious feeling of care evoked by the Mother Teresa video. In some individuals, IgA increased as much as 240 percent immediately after they performed the FREEZE-FRAME technique.

There was also an immediate increase (18 percent) in IgA levels when the participants experienced anger. But an hour later, their IgA levels had dropped to only about half of what they were before the anger. Even after six hours, their IgA levels were still not back to normal. [16]

One five-minute experience of recalled anger and the effectiveness of our immune system is impaired for over six hours. Clearly, it takes a long time for our system to come back into balance once anger kicks in. And yet how many times each day are we faced with situations that have the potential to arouse anger? If simply remembering an angry feeling can have such an enormous impact on our defense mechanisms, imagine the impact when we have a real-time anger outburst!

FIGURE 8.2. This graph compares the impact of one five-minute episode of recalled anger against that of a five-minute experience of care on the immune antibody secretory IgA over a six-hour period. When subjects recalled an angry feeling for five minutes, an initial slight increase in IgA was followed by a dramatic drop, which persisted for the following six hours (bottom trace). In contrast, when subjects used the FREEZE-FRAME technique and focused on feeling sincere care for five minutes, there was a significant increase in IgA, which returned to baseline an hour later and then slowly increased throughout the rest of the day (top trace).

© copyright 1998 Institute of HeartMath Research Center

By taking McClelland’s study further, Rollin discovered that while feelings of anger suppress the immune system, self-induced care boosts it significantly.

It’s good to know that an intentional focus on caring is more powerful than the care we feel when watching a compelling movie. But if we never focus our attention on caring, we can’t consciously produce that effect. How often during the day do we make an effort to feel care? Once, twice, maybe three times? And by contrast, how often do we feel worried or anxious? More than once or twice? Worry and anxiety are the black sheep of the family of care. They’re care gone awry—what researchers at the Institute call overcare.

Here’s something very interesting. In Webster’s dictionary, the first definitions of care are “a troubled state of mind; a suffering of mind, grief; a burdensome sense of responsibility, anxiety, concern, solicitude and worry.” Those words certainly don’t capture the feeling a mother has when holding her newborn baby, does it?

Webster’s definition seems to have missed the first priority of care as a supportive, loving feeling. From our perspective, the burdensome state described in the dictionary definition is closer to what we define as overcare. When care from the heart is bombarded by niggling worries, anxieties, guesses, and estimations from the head, it can degrade from a helpful experience into a harmful one.

Overcare is one of our biggest energy deficits, and it’s at the root of a lot of other unpleasant emotional states, including anxiety, fear, and depression. Overcare has many forms. Some are obvious, and others are more subtle. Overidentity, attachment, worry, and anxiety are but a few of overcare’s incarnations. And while overcare in its various forms often shows up in our relationships with spouse, children, and friends, it can also tinge our relationships with things and concepts. It can, for example, take the form of overidentity with or attachment to issues, attitudes, places, things, and ideas. It can be about the environment, politics, job performance, our material possessions, our pets, our health, our future, or our past.

Because it’s born from care, overcare can be hard to see. What distinguishes overcare from care is the heavy, stressful feeling that accompanies it, while true care is accompanied by a regenerative feeling. It’s terribly important to care, but if we cross the line to overcare, what we feel is worrisome and stress-producing. A good question to ask ourselves is whether our care is regenerative to both the caregiver and the other recipient. If our caring intentions don’t feel as if they’re both adding to our energy bank account and affecting others in an uplifting way, then there’s a good chance we’re in overcare.

Overcare siphons off the potency of our intended care and reduces its effectiveness. Getting worried and upset doesn’t help anything or anybody, even if we’re worried “because we care.” Problems get solved as we attain clarity and coherence, not as we worry. In fact, overcare can actually make things worse: smothering a loved one with overcare and worry tends to repulse instead of attract. Nobody likes to be nagged and worried over for too long.

Overcare is one of the main reasons people in ministerial and other care-giving professions burn out. But even those of us who are bankers and at-home moms and gardeners know what burnout feels like; at times we’ve all felt used up, dried up. In some institutions—many hospitals, sanitariums, hospices, and convalescent homes, for example—overcare has largely replaced true care. Why? Because the original, caring intentions of those who work in such institutions—intentions born from the heart—are often drained by the unmanaged mind and amalgamated with the incoherent energy of emotional discord.

It’s essential that those who work with others in emotionally challenging situations stay balanced in order to sustain their effectiveness. If a nurse, for instance, falls into the trap of overidentifying with every sick patient—taking her work home with her, worrying about those on her ward, and taking on too much responsibility for the outcome of their health dilemmas—the overcare will sap her energy.

Soon she’ll feel that she has to keep a greater distance than normal from her patients to protect herself from emotional exhaustion. And yet that distance cuts her off from her heart. And without heart, she can’t fully enjoy her job. She forgets why she became a nurse in the first place. That’s because when she can’t afford to care anymore, she doesn’t feel like a caregiver.

What she doesn’t realize is that there’s another option—staying in her heart, continuing to care about her patients without overcare. Mother Teresa couldn’t have worked all those years with some of the sickest and poorest people in the world without a huge heart that understood the difference between true care and overcare.

Jerry Kaiser, director of the Health Programs Division at HeartMath LLC, used to work with an organization that provided disaster relief for victims of hurricanes, floods, fires, and other catastrophic events. “When the relief teams came in,” he said, “you could always tell the novices. They’d go immediately into overcare: ‘Oh, no! Look at these poor people!’

“Those of us who were experienced would shake our heads. We knew that, at that level of emotional drain, these well-meaning volunteers were no good to anyone. After a day or two, they’d hit burnout and we’d have to send them home.”

If we care to the point that we drain our emotional reserves, we simply don’t have the energy or inclination left to care about much of anything. Overcare is the fast track to burnout. And burnout leads to no care at all.

In order to eliminate the drain of overcare, we first have to become aware of the ways in which we tend to experience overcare. Everyone is different. Some of us are naturals at overidentification with factors such as physical appearance, job status, or ideas. (Yes, that’s overcare too!) Others of us have overattachments to people, money, things, or issues. Under the influence of overcare in any of these guises, we’re more likely to give in to worry, anxiety, anger, or fear. Pick your poison. We all have our favorites.

Luckily, listening to our heart intelligence is the best way to discover where we’re expending energy in ways that aren’t efficient. As we develop more of this intelligence, we’ll naturally become more cognizant of our overcare.

You can start right now, if you haven’t already, by making a list of your major overcares. What causes you worry and anxiety? What are you overattached to or overidentified with? Remember, overcare can be present in almost any area of your life—people, pets, things, beliefs, time pressures, or issues. It can be obvious or subtle. The overcare emotions you should be on the lookout for include anxiety, fear, depression, worry, disappointment, guilt, jealousy, and stress. All of these can range in intensity from mild to strong.

Take a few minutes to look objectively at your overcares. Write them down on the overcare inventory sheet found on page 168. This exercise isn’t designed to cause you alarm. If you find yourself overcaring about your overcares, relax and shift into the area around the heart; then find a core heart feeling. Try to relieve any anxiety you have by accessing the heart.

When you find yourself caring too much, the best thing you can do is engage your heart power and find a feeling of balanced care. This process involves taking some of the significance out of the issue and reducing the amount of emotional energy you have invested in it. As you might imagine, FREEZE-FRAME can be very useful in managing overcare. You’ll learn another technique in the next chapter—CUT-THRU—that will further eliminate overcare, especially when there’s a lot of energy associated with it.

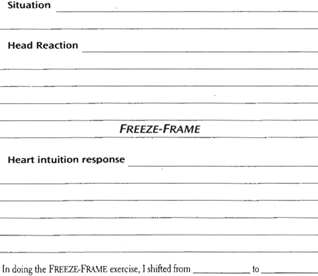

Now fill out the FREEZE-FRAME worksheet on page 170—the same worksheet you responded to in Chapter 4. Pick one of the issues from your overcare inventory sheet. Write it down under “Situation”; then, under “Head Reaction,” write down a few words about how you perceive the situation and how it makes you feel.

Overcares are caused by the unmanaged head and cellular memories that drain our power. Identifying overcares is the first step in cutting through them.

Overcare feelings include:

• Uneasiness

• Worry

• Disturbed or vague insecure feelings

• Jealousies

• Fears

List overcares that are drains in your life right now, such as:

• Worry about what someone might think about you

• Insecurity in relationships

• Money concerns

• Health concerns

• Anxiety about work performance

• Uneasy feelings about certain people, issues, situations, life

Having set the stage, now do the FREEZE-FRAME technique and ask your heart to show you how to move from overcare back to true care; listen well, and then write down (under “Heart Intuition Response”) what your heart says. Compare the before and after perspectives. See if you’ve determined a more efficient way to deal with your situation—one that eliminates some of your over-care and brings you back to balanced care. Most important, follow through on the advice your heart has offered you.

Don’t worry: everyone experiences overcare to some degree. By identifying and then working to eliminate it, you’ll be taking a major step forward. And as you continue to move ahead, you’ll get to the core of what causes a lot of the hidden stress that prevents you from experiencing a more rewarding life.

Overcare encompasses and gives birth to many of our least desirable emotional states. As we’ve seen, emotions such as disappointment, guilt, anxiety, and envy—along with many others—are often born from overcare. So are fears and insecurities, which stack up and multiply if they’re not resolved. The interesting thing is that if we deal with our overcares from the heart, we eliminate a host of other emotional conditions at the same time.

Left unchecked, overcare eventually produces a low-grade angst that hangs like a cloud over every aspect of our lives. And that low-grade feeling escalates if not arrested, eventually becoming fear or even panic. Before we know it, fear starts to run the show—fear of everything. We can eliminate much of this emotional behavior by catching overcare early.

Since catching it requires recognizing it, let’s take an in-depth look at some of the common forms overcare takes.

Let’s begin with fear. Although most of us don’t experience high levels of fear in our daily lives, we do feel emotions that are fundamentally fear-based, such as anxiety, worry, panic, and insecurity.

FREEZE-FRAME Worksheet

Here are the five steps of the FREEZE-FRAME technique:

1. Recognize the stressful feeling, and FREEZE-FRAME it. Take a time-out!

2. Make a sincere effort to shift your focus away from the racing mind or disturbed emotions to the area around your heart. You can pretend that you’re breathing through your heart to help focus your energy in this area. Keep your focus there for ten seconds or more.

3. Recall a positive, fun feeling or time you’ve had in life and attempt to re-experience it.

4. Now, using your intuition, common sense and sincerity — ask your heart, what would be a more efficient response to the situation, one that will minimize future stress?

5. Listen to what your heart says in answer to your question. It’s an effective way to put your reactive mind and emotions in check — and an “in-house” source of common sense solutions!

© Copyright HeartMath LLC

Generalized anxiety is one of the most common of these. And we often feel it for no apparent reason. But there’s a reason hidden somewhere: maybe we’re too concerned about a specific problem or too attached to its potential outcome. And there’s a consequence as well: the habitual or ongoing experience of anxiety fosters insecurity. And left unchecked, it produces fear and panic.

Say you have a ten-year-old son who’s just left for summer camp: He’s never been gone for a whole week before, and although you try not to show it, you’re feeling a little anxious. In your heart, you know that the camp counselors will watch out for him, but the more you think about it, the more anxious you become. After all, he’s just a little boy. Without you there, he might fall out of a tree and break his neck, or drown in the lake—anything could happen!

When a child’s safety is involved, the progression from anxiety to worry to fear to panic is a pretty quick one. But if you learn to nip anxiety in the bud, you save yourself from hours of bombardment by stressful hormones. Best of all, you avoid feeling insecure or frightened altogether.

More often than not, as we’ve seen, anxious feelings are directly associated with overcare of some kind. Performance anxiety is a perfect example. It’s over-care about whether we’ll meet the expectations of ourselves and others. How will we do? Will we get everything right? What are others going to think?

All of these thoughts and feelings come from overcaring about our self-image and/or overcaring about measuring up to a personal or social standard. It’s important to care about doing things well, of course. But when we cross the line into overcare, our original caring is tainted by stress. It then becomes self-defeating, because it compromises our available energy to perform.

In the workplace, where competition is high, performance anxiety can reach extreme levels as people work harder and longer trying to stay ahead. Anxiety about time pressures, deadlines, communication issues, and information management is prevalent, as is anxiety about position, status, salary or benefits, raises, and performance appraisal.

Among top-level athletes, performance anxiety is such a common problem that many psychologists have built their career around the treatment of this one issue. From the snowy mountaintops of professional skiers to the playing fields of major league football stars, sports psychologists stand alongside their clients and remind them to relax, to keep their focus, to put everything else out of their mind. Their athletes know only too well that anxiety is the kiss of death for their performance.

Setting high goals is admirable, as is working hard to achieve them. But worrying about them is a debilitating waste of energy. It’s overcare.

Perfectionism works the same way. It sets us up for inefficient emotions such as disappointment, self-judgment, and guilt. Nothing can be just good or even exceptional. It has to be perfect. Getting a B+ isn’t good enough; you want an A. Being a successful, appreciated, well-loved wife or husband doesn’t interest you; you have to be flawless. Perfectionism is overcare at its height.

Let’s say you’re planning a birthday party for your mother. It will soon be her eightieth birthday, and you want everything to be just right, because you always strive to be the perfect daughter. Perhaps over the years you’ve been taught to be perfect and you’ve bought into that goal, living in unconscious overcare about always hitting the highest standard.

You plan and plan for the party, overcaring as you go. Will you get the exact table you’ve requested at the restaurant? Will your brother, who’s notorious for being late, show up on time? Will your mother have a good time? Will you receive acknowledgment for creating the perfect birthday party? You’re increasingly anxious, wondering if you’ve attended to all the details. Everything has to go exactly the way you’ve planned it, or the party (and you) will be a failure.

Predictably, your brother is late arriving at your home. All of your overcare had no effect on his sense of punctuality. When he’s only minutes late, you start to resent and judge him. Even though you drive a tad faster than the law allows, you’re late getting to the restaurant, where you find that your special table has been taken. It’s so typical, you think.

Your mother is fine, though, enjoying the time with her children and feeling honored that everyone cares enough to make this a special night. She’s not in overcare about what table she sits at. But you feel disappointed and frustrated. Instead of having a lavish bouquet of love to offer your mother on this special birthday, you have only remnants of your loving intentions, and these are now intermingled with disappointment and resentment.

Your overcare has compromised the potency of your intended care in the name of perfectionism. And you’ve drained your energy. You wouldn’t harm yourself that way if a little more heart security, flexibility, and emotional balance were present.

Overattachment is a feeling that binds us to a person, place, object, or idea to the extent that we lose balanced perspective. A mother has a natural feeling of attachment to her child. However, if she attaches herself to the point where she can’t bear to be apart from the child, her attachment promotes dependency, reinforcing her own and her child’s insecurity and unhappiness.

Spouses and lovers have a natural attachment to each other. The feelings our partner kindles in us, the support and comfort he or she gives, can be tremendous assets. But if we become dependent on this attachment, we lose our own center of power. Everything the other person does (or doesn’t do) becomes a source of security (or insecurity). This ill-grounded security distorts our perceptions of ourselves and of our partner. It’s false security. Comparisons, jealousy, fear of loss, and actual loss are common outcomes. Relationships simply can’t flourish with overcare-driven attachment.

We can also build attachments to attitudes and habits. We get in the habit of having an early-morning cup of coffee, for example, or folding the clothes a certain way, or adhering to our opinions so rigidly that we’re loathe to let them go. If something interferes with our routine, we let it throw us into a “justifiable” funk. At that point, we’re so set in our ways that we’ve lost our healthy flexibility. Yet we all know that what doesn’t flex eventually breaks. Overattachment to our attitudes and routines is trouble waiting to happen.

In business, companies these days are spending millions of dollars training employees to “think out of the box.” The “box” referred to in that term is made of rigid mind-sets and the inability to expand awareness. Attachment to ideas or ways of doing things limits new possibilities and can make us feel as if we’re stuck in a box. A quick way out of the box can be found by developing a joint venture between the head and the heart.

Overattachment to expected outcomes or results also indicates overcare. When we add attachment to our expectancies, we set ourselves up for disappointment. If life were trying to teach us how to loosen up, this would be the perfect opportunity. The good thing about not having our expectations met is that it forces us to rethink our attachments.

As we learn to identify overcare and then make inner adjustments to recapture the feeling of true care, we remove the foundation that supports our draining emotions. That single act brings us back into balance. It’s an efficient approach to emotional management, because it takes us to the source or cause of many emotional issues.

From time to time, when you’re feeling emotionally out of balance, do a system check to track down any overcare that might be behind your inharmonious feelings. Once you recognize overcare in one guise or another, go to the heart and do something about it.

Worry, anxiety, and insecurity are some of the most obvious results of care running amuck. Though these feelings can sneak up on us when we least expect them, we generally know that they’re there. But many subtler forms of overcare easily go unnoticed in our thought world.

Most people wouldn’t think of projections, expectancies, and comparisons as overcares that need to be dealt with. These forms of mental overcare are often the culprits behind other, more noticeable unpleasant emotional conditions. In the end, they can produce large energy drains on our health and lead to breakdown. When Mark Twain said, “There’s been a lot of tragedy in my life. At least half of it actually happened,” he was referring to the misery that unmanaged projections can cause us.

We use the term “projection” to describe our thoughts and mental images about the future. We all have literally thousands of thoughts about the future every day—whether it’s making a shopping list for the week or planning a business meeting for next Thursday. Our long-term goals, which are invaluable for keeping our lives on track, inevitably project into the future. Hopes and dreams keep us enthusiastic about the future. But when fear and anxiety attach themselves to our projections, that’s something else entirely.

Projections create untold emotional drains, but we’re not usually aware of how extensive those drains are. The big deal about projections is their cumulative effect. Though most of us don’t recognize projections as problems—after all, everybody projects into the future—drop by drop they leach away the energy we need to create a positive future. As a result, we don’t have enough energy to experience “quality” in our life. Everything may seem okay on the surface, but something’s still missing.

If we walk across the desert with water in a bucket full of holes, we’re not going to have anything left to drink when we need it. The more holes, the faster the water is depleted; but even one hole would drain the water out. That one hole could be a projection that drains the bucket in fifteen steps or in three miles.

Most of us have low-grade projections operating constantly all day long. Even if individually they seem like no big deal—each one just a pinhole hole in our bucket—remember that it takes only one leak to drain that bucket dry.

It’s just physics: energy has to be accounted for. When we extend our fears and insecurities by projecting them into the future, we encourage more fears to rush in, creating an even greater energy drain. If we believe in those fears, we actually help create what we most fear.

Think about it. How much energy is spent wondering about how things will work out? How often do we project that we won’t have enough time, won’t meet an important deadline, or won’t be able to communicate with someone? How much are those projections and overcares costing us? The energy drains they initiate won’t stop themselves. It’s up to us to notice and stop them.

Have you ever left the house on a trip and started worrying, after you were miles from home, about whether or not you turned off the oven? You’re almost certain you did, but what if… ? If you have reason to think you really might have left the oven on, then taking action is an appropriate response. Stop at your first opportunity and call to have a neighbor check it out. That’s natural and responsible. But if you’re picturing your entire house burning down on the basis of an unsubstantiated what-if, you’re in overcare projection. And all that fretting and worrying will register as a deficit on your inner asset/deficit balance sheet.

We can also experience projections around long-term issues such as finding fulfillment or success, meeting the right mate, getting the right job, raising well-adjusted children, and so on. Considering our future is in and of itself very appropriate—but not if that consideration turns into overcare, producing a fearful wondering about future security for ourselves and others. That kind of projection doesn’t serve us or anybody else well.

Here’s another interesting example. We like to call it “high-speed projection.” Have you ever found yourself saying, “Life sure is going well. I wonder when that’s going to end and things are going to change for the worse?”

Right in the middle of good times, with no reality-based reason, we can sabotage our well-being by overcaring and projecting about what might happen. The thoughts and feelings of pending disaster fly through our minds at high speed. We don’t even know what hit us. Without realizing it, our speculation has inhibited our ability to be as fully appreciative of our current situation as we could (and should) be.

And what about idealistic projections? We imagine a glorious new career or wonderful vacation and invest our hopes and identity in that, then end up devastated if the reality doesn’t match the projection.

Projecting outcomes is automatic in most people. In fact, everyone does it, though to different degrees. It’s not bad, but it’s wise to learn how to manage your projections.

Since the thoughts and feelings of projection can be subtle, ask your heart to help you see them. Try not to identify with them as you observe them. Go to neutral and let your heart intelligence show you a different perspective. It takes a fine-tuned level of emotional management to stop projections as they arise. Then appreciate your life without worrying or projecting a future reality that may or may not actually happen.

We generally take it for granted that we’ll be treated with respect and good manners by our family, our co-workers, even our waiter at a restaurant. Whether people actually treat us that way or not, we all have expectations. We also expect predictable results from our efforts. We expect meetings to take place on schedule. We expect people to do what they say they will. And when things go wrong, we feel entitled to the stress we feel. And all too often—in all these many ways—expectancy leads us around by the nose.

When we care too much about life’s conforming to our expectations, we’re setting ourselves up for disappointment. As we all know, life just isn’t that compliant. Reality will eventually—and often—fail to meet our expectations. The disappointment we feel can lead to despair, which can then become depression. We feel like victims. All of this takes a toll on our bodies and negatively impacts our longevity.

Expectancy also leads to blame, which consumes a lot of energy and doesn’t fix anything. It just makes things continually worse. Blame drains the blamer. It’s not the thoughts of blame that cause the heaviest drain, though; it’s the significance and emotional energy that go into supporting the blame.

Years ago, when I (Doc) got out of school, I took a job at a furniture factory. One day my car broke down and for a period of many weeks I would need a ride to get to work.

A friend agreed to give me a ride regularly if I met him halfway down the road between our houses. Things went well for a couple of weeks. I was glad I could count on him while my car was being fixed.

One morning it was raining as I trudged down that dirt road to meet my ride. I stood expectantly, getting wetter and wetter, as I waited for my friend. He never showed up, though he knew I was depending on him. I couldn’t believe it. I was so disappointed that I couldn’t think straight.

After unsuccessfully trying to hitchhike, I finally knocked on a stranger’s door, dripping wet, and called a cab. And I decided to take a cab from then on. I . left him a message to that effect but offered no explanation.

When I finally got my car back, I ran into my friend and unloaded on him. Nothing I said had to do with my appreciation for the fact that he’d indeed picked me up without fail for a time before letting me down.

He said he’d tried to call me that rainy morning to explain that he’d had a flat tire. Eager to make things right between us, he even showed me the receipt for the new tire. I quickly realized how foolish I’d been to hold a grudge against him for so long. I almost lost a good friend because my idealistic expectations weren’t tempered by a consideration of life’s unexpected occurrences.

It’s odd when you think of how idealistic our expectations can be. They’re fantasies about the way we’d like life to work, nothing more. We can’t control how everything will turn out. And even when everything goes right, sometimes we mess things up ourselves. How can we hold others to a higher standard than ourselves?

The positive power of expectancy is found through the heart. But that power is only as positive as your ability to release your expectation if it isn’t fulfilled, take on a new, more realistic perspective, and cut your losses.

In this context, comparison means measuring ourselves against others—assessing who we are (self-image) and what we have versus who someone else is and what she has.

Comparisons that cause emotional stress arise out of our own insecurities and frailties. For example, we can overcare about whether we’re as smart or as beautiful as someone else and lose sight of our own good qualities. We can envy other people’s acquisitions and achievements—their cars, their families, their houses, their jobs—and completely miss how happy we could be in our own lives if we’d stop comparing. Feeling this sort of comparison is very different from having successful role models or a healthy admiration for other people.

Status is a common comparative playground. “Do I have as much [money, prestige, you name it] as he does?” “Is our son going to get into as good a college as our neighbor’s daughter?” “Don’t I deserve the corner office just as much as my colleague does?” “Isn’t my job as important as my friend’s?” All these questions reveal overcare about what we have versus what others have.

If we’ve taken an honest inventory from the heart in the previous exercises, we may now be feeling that we have more than we thought we did. Still, though, we always want more (and feel entitled to more). That’s due in part to a natural urge for growth and fulfillment, but comparisons make us lose perspective and choke appreciation for all that we do have.

A mutual friend inherited a substantial amount of property, stocks, and personal belongings when his mother died. His brother received an inheritance of equal value, but he was also given their mother’s diamond wedding ring. When he found out about it, our friend went into extreme overcare. He started obsessing about why his brother got the ring. It had been so important to their mother, he said. Did this mean she loved his brother more? Working himself up into a frenzy, he began questioning everything about their inheritance, trying to second-guess their mother’s decisions: “Why did I get the house while my brother got the farm? Is the farm better? What was she trying to say?”

With overcare coloring his perspective, our friend saw every innocent line in the will, every generous bequest, as a potential source of pain. After many miserable weeks, he gradually let go of his perceptions and made peace with his mother’s decisions. He realized that he didn’t really doubt her love for him and that he had, in fact, received a wonderful inheritance, ring or not.

If comparison runs away with us, it leads to envy and jealousy—fertile ground for other deficit emotions, such as blame, resentment, and even hate. Think about it. We can start out caring about something or someone and, because of a single jealous thought, end up resenting or even hating that thing or person. That’s the potential of unmanaged overcare.

With overcare, the focus is on what we don’t have in comparison to others. Overcare not only reduces appreciation of what we do have but also seriously lowers our self-appreciation and self-esteem. The solution, of course, is to develop a stronger sense of inner security. Heart intelligence helps build security, but it won’t happen overnight.

If you’re in the habit of making unfavorable comparisons between yourself and others, you’re in the habit of being too hard on yourself. It’s just not possible that you’re worse at everything than everyone you know. So it’s important that, from the moment you decide to work on this element of comparison overcare, you lighten up. Give yourself some self-care. The best way to stop making comparisons is little by little. Realize that a lot of our overcares come from social programming in our families, schools, and society. Appreciate yourself for improvements as you go instead of expecting instant success.

When we check projection, expectancy, and comparison at the door, balancing our overcares with the wisdom and care of the heart, we leave room for human frailties and for life to be life. We realize that growing up emotionally entails not expecting everything to meet our expectations. That realization helps us sincerely care about things without slipping into overcare, which means we don’t have to go through the stress that overcare creates.

Here are five tips that can help to eliminate projection, expectancy, and comparison:

1. Become observant of your thoughts and feelings and make a sincere effort to see where you might be prone to regularly experiencing overcare.

2. When you find yourself experiencing unhealthy projection, expectancy, or comparison, remember that those energy deficits are draining your energy reserves. That perspective will give you the motivation needed to move beyond them.

3. Try to take some of the significance out of projective, expectant, and comparative thoughts and feelings. They’re usually not as important as they seem.

4. When you find yourself experiencing any of these overcares, make, an effort to stop, do a short FREEZE-FRAME, and ask your heart to show you how to transform each overcare into true care. Making contact with your heart intelligence will allow you to see things in a more comprehensive way and give new direction for your care.

5. Activate the core heart feeling of appreciation. Appreciate the way things are instead of overidentifying with a situation or issue, and appreciate yourself for having the awareness to catch these subtle overcares.

Learning to care more for yourself and others isn’t about being flawless and never experiencing overcare. It’s neither an instant nor a finite process. It takes time to weed overcare out of your life, and the process is ongoing, but it’s actually fun to start looking for overcare and freeing yourself from it.

As your heart intelligence becomes more readily accessible, you won’t have to be on the lookout for every stray thought or feeling. The signals from the heart will be clearer, letting you know without prompting when your care has become overcare. Every time you eliminate an overcare, the relief will be tremendous, and you’ll store away power that will make dealing with overcare easier the next time.

Soon you’ll discover for yourself that transmuting overcare into true care is one of the most rewarding and regenerative accomplishments you can experience. Eliminating overcare is an act of self-care that will enhance your life in ways you’ve never imagined. It will also enhance your ability to intelligently care for the people and social issues that are important to you.

Often, when we’re giving a seminar, we talk about cultivating self-care. Most participants love the concept—and why not? Just the idea feels nurturing and good to our souls. Most of us were taught to give ourselves the short end of the stick. Setting aside time to care for ourselves seems like a luxury.

Because of inexperience, the first things that come to mind around self-care are fairly simple. “Hugging my puppy makes me feel so good that I’ll do it more often!” a student might say. Or “I know: I’ll light some candles and take a long, hot bath.” Great suggestions. But self-care goes much deeper than that.

Caring for yourself enough to generate love for yourself throughout the day—for no reason at all (except that you’re worth it!)—sends a strong message to your heart. Once it knows what you’re up to, it will begin to help you generate that love. This isn’t narcissism; it’s self-health. Eliminating overcare and other energy drains is most quickly and painlessly accomplished by stepping back from the clatter of the mind and letting yourself be motivated by a deep sense of self-care. With self-care, you’ll begin to amplify your capacity to care until it naturally flows out from you to yourself, your loved ones, and the world around you.

Care is a valuable and vital resource, far more precious than people realize. It revitalizes you and acts as a soothing tonic for the human system.

Yet people squander their care in overcare, then burn out and end up with no care at all. Many personal, interpersonal, and social problems will be solved as humanity develops a more mature sense of care. At the deepest level, it’s real love and care that people crave. Give those things, and you’ll receive them. Through your caring deeds and actions, you’ll truly make your mark on the world.

It’s not care, but overcare, that stops most people from caring. Overcares will come and go, but it’s important to remember that we have to care in the first place to get into overcare. It’s about balance, about walking a fine line. And the heart can give us that balance, allowing us to express our care without letting its regenerating warmth and reassuring power slip away.

In today’s culture, unconscious overcare for ourselves and issues is so rampant that it’s become a social disease. It spawns stress in mega-doses, creating so much incoherence in people and society that it ranks at the top of the list of human energy drains. The importance of eliminating this stressor can’t be stated too strongly.

Care paves the way for intuition. Overcare then comes along and eats up the pavement, leaving us without a road to travel on. That’s why we don’t get anywhere. Care provides a conduit for our spirit’s expression in the midst of our social existence. The more we truly care, the more we’ll come to know ourselves and others. Care provides the key to unlocking our potential and making it real. The bridge between all that we can be and all that we are lies in the heart. There we can find the bridge of care clearly marked.

![]() Care is a powerful motivator. It inspires and gently reassures us. Care feels good—whether we’re giving or receiving it.

Care is a powerful motivator. It inspires and gently reassures us. Care feels good—whether we’re giving or receiving it.

![]() Research shows that feelings of care boost the immune system, while feelings of anger suppress it significantly.

Research shows that feelings of care boost the immune system, while feelings of anger suppress it significantly.

![]() When care from the heart is bombarded by worries and anxieties, projections and expectations, it degrades into overcare.

When care from the heart is bombarded by worries and anxieties, projections and expectations, it degrades into overcare.

![]() Overcare siphons off the potency of our intended care and reduces its effectiveness. Problems get solved as we attain more clarity and coherence, not through worry.

Overcare siphons off the potency of our intended care and reduces its effectiveness. Problems get solved as we attain more clarity and coherence, not through worry.

![]() Thousands suffer from overcare-driven exhaustion and burnout. They feel that they’ve cared too much and can’t care any more.

Thousands suffer from overcare-driven exhaustion and burnout. They feel that they’ve cared too much and can’t care any more.

![]() Overcare that’s left unchecked eventually produces a low-grade angst that hangs like a cloud over your entire life.

Overcare that’s left unchecked eventually produces a low-grade angst that hangs like a cloud over your entire life.

![]() Signals from the heart let you know when your care has become overcare, if you’re willing to listen. Every time you eliminate an overcare, the relief is tremendous, and you store away power that makes fighting overcare easier the next time.

Signals from the heart let you know when your care has become overcare, if you’re willing to listen. Every time you eliminate an overcare, the relief is tremendous, and you store away power that makes fighting overcare easier the next time.

![]() By identifying and then working to eliminate overcare, you approach the core of what causes a lot of the hidden stress that prevents you from experiencing a more rewarding life. Eliminating overcare is an act of self-care that will enhance your life in ways you’ve never imagined.

By identifying and then working to eliminate overcare, you approach the core of what causes a lot of the hidden stress that prevents you from experiencing a more rewarding life. Eliminating overcare is an act of self-care that will enhance your life in ways you’ve never imagined.

![]() Care provides a conduit for your spirit’s expression in the midst of human existence. The more you truly care, the more you’ll come to know of yourself and others.

Care provides a conduit for your spirit’s expression in the midst of human existence. The more you truly care, the more you’ll come to know of yourself and others.

![]() A return to care is at the top of the list when it comes to societal need.

A return to care is at the top of the list when it comes to societal need.