STORM COMIN’

Perry tried to move and failed. He could no more stand up or withdraw his hand than he could spit out a squadron of flying monkeys. He would have been afraid, but Peaches was with him, even if her presence had taken on a strange dimension.

“Just a minute, Peaches,” Brendy said. She lowered her voice for privacy. “You done good, Billy.”

“Need me ’gain?” Billy asked quietly in its borrowed Brendy-voice.

“I dunno. Hang around a bit, and we see, okay? How I get you to come out the rock when I need you?”

“Haniran sayala alagbara! Brendy say.”

“Haniran see olla alagbera!” Brendy repeated.

“Haniran sayala alagbara!”

“Haniran sayala alagbara!”

“Yes!” Billy said happily. “Just like!”

Brendy repeated the incantation over and over again as she approached, then stopped as she knelt across from Perry on Peaches’s other side. “This shonuff crazy,” she said. “Magic bags, magic rocks, and fire under the water.”

“Baby, who you tellin?” Peaches-in-Perry said. “This too much for even me. I quit.”

“You quit?” Brendy asked.

No, Perry thought. You can’t quit. We need you. But Peaches didn’t seem to hear.

“This too much,” Peaches-in-Perry said sadly. “I’m all burnt up. My hair got burnt up. I just wanna go home, feed Karate, make sure Honcho ain’t bothering Dudley, and wait for the next letter from my daddy. I can’t do that right now, so I’ma stay sleep. Just lie right here.”

“Peaches,” Brendy said tenderly. “It’s scary. It’s a lot, even for you. But we gots a secret weapon.”

“Oh yeah?” Peaches said. “What that is?”

“Perry,” Brendy said matter-of-factly.

“What Perry gonna do if Gun Man come at me again?”

“Oh, well, Perry kill him,” Brendy said without hesitation.

Hey, Perry thought. Hey, now. I don’t even know if he can be killed in the first place! I think he already dead!

“Perry get scared sometimes,” Peaches said. “He freeze up. How he gone have my back?”

“We all get scared,” Brendy said. “But Daddy Deke told me being brave ain’t about not being scared. Being brave about doing what you gotta even if you scared.”

Perry wanted to protest again, but he had nothing to say to that.

“Girl, you seen how Perry went after Jailbird? He was like a cop show on the TV. He was all, ‘Take me to Daddy Deke, or I put it on you!’ And, baby, I seen the look in his eye. He wasn’t playin’.”

Perry’s chest swelled a little. Had he really sounded like a cop show?

After the Hanging Judge threatened him, Perry felt as if a door had closed deep inside him. It didn’t feel like a normal door. This one felt heavy, old as the Earth itself, and heavier even than the gate to Superman’s Fortress of Solitude. He felt as if he stood in shadow, as if laughter and sunlight could still touch him, but that they mattered less. He mattered less. Spending time with Peaches—adventuring through the city, or just playing board games or watching cartoons—parted that gloomy haze for him, made him feel as if maybe that door wasn’t fully shut. That it might open for him again on some far-off day.

Perry’s dream-that-was-not-a-dream made his world, his life, seem small and grimy, but Peaches represented pure possibility for Perry. Maybe there were some things not even she could do, but it didn’t matter. She was capable of so much, she was so free, that sometimes Perry thought that maybe he was free, too. Maybe everyone was, had been always, and when they felt chained or trapped it was because they’d been lied to, or they were simply mistaken.

“And then when the Bad Man shown up, Perry turnt around and looked him right in the eye—after the Bad Man started shootin’! Looked him right in his face, girl! And when the man started breathin’ fire, Perry didn’t stop to think. He just said his Words and got us right out of there…”

He had read once that knights were not created by the accolade, the tapping of the sword blade on one shoulder and then the other. That the ceremony recognized something that had already happened. Not “We dub this man a knight” but “We find that this man has become a knight.” It would be many years before Perry would be able to parse these ideas, express them to himself, but he was aware of them just the same. That awareness felt too enormous to express with language, too secret to share with the outside world.

Brendy harrumphed a little and arranged her legs underneath her. She stroked Peaches’s shoulder, but looked Perry in the eye. “My brother ain’t perfect, Peaches,” she said. “He make me mad sometimes. Sometimes I get so mad, I could spit. And I yell at him, and sometimes I even kick him. But, Peaches, you gotta know. Perry do anything for the people he loves. Anything. He loves me a lot. But he love you different. He gets… His voice change when he talk about you. It gets all soft.”

Hey, Perry thought. Hey, now.

“And when he go too long without seeing you, he get all mopey and grumpy,” Brendy said. “Jokes ain’t funny to him, and he make this face.”

Brendy squinted her eyes, poked out her lower lip, and groaned like a sick bear.

“What face?” Peaches said. “My eyes is closed! I can’t see!”

“I show you,” Brendy said. “Open your eyes and look.”

Perry’s paralysis evaporated so quickly that he pitched to his right, balance gone. He rolled onto his back and stared up at the luminescent fog. Away to his right, Peaches burst into helpless laughter. “He do not!” she gasped. “Perry do not make that face!”

“Hand to God,” Brendy said. “Listen.”

The girls quieted. Perry’s face burned as he felt Peaches’s gaze sweep over him.

“He all embarrassed,” Brendy said. “He gone be mad at me for a week.”

“Perry. Hey, Per-ry,” Peaches called in a playground singsong.

Perry didn’t answer. He tried not to be angry—he understood why Brendy had said what she said. He understood that any sacrifice that resulted in Peaches rejoining the fight was one worth making, but… but he didn’t know how he’d speak to his friend or interact with her now that she had some inkling of the mad boil of emotions that gave him such sweet trouble when she was around—and especially now that she knew those emotions made him even crazier when she wasn’t around.

Perry covered his face with his hands. He wished they were bigger. He wished they could swallow his whole head.

A deep shiver ran through Perry’s body as Peaches’s cool dry palm touched his right arm just above the elbow.

Peaches didn’t withdraw, but she didn’t say anything, either. Then, “Perry,” she said. “It’s okay. I like that you care bout me.”

Perry took a breath, lifted his hands from his face. He still couldn’t quite look at Peaches. “I don’t just care about you,” he said. “You don’t make me strong.”

Peaches grinned so hard that Perry felt the full force of her expression without looking directly at her. “What you mean?”

“You don’t make me strong, and—and you don’t make me free. You help me remember that I am strong. That I am free. Always.”

Peaches began to laugh. The hand on Perry’s arm fluttered against his shirtsleeve like a nervous bird, and she rested her other hand on Perry’s heart. He wondered how much effort she had to exert to keep from hurting him with her titanic strength. “That’s a lot,” she said. “That’s so much.”

“I know. Too much?”

“No,” she said. “It’s what I want. It’s what I need.”

Perry sat up and drew Peaches to him. He wrapped his arms around her and pressed his lips against her forehead. She trembled against him.

“Perry and Peaches,” Brendy sang, but her tone did not mock. “Sitting in a tree. Kay, eye, ess, ess, eye, en, gee!”

“Aw, hush,” Peaches said, but she didn’t pull away.

They relaxed, resting in the moment, together in a new way that Perry wasn’t sure he understood—that he didn’t think he needed to.

“… So what about it?” Peaches said softly after a while. “Where we is, and how we get back to the city?”

Perry barked a laugh. “Baby, you got me!” he said. “Lord only knows.”

Prison is as prison does, Deacon thought darkly. His mama would be so disappointed if she knew. This wasn’t a room; it was a cell. All those years he’d spent doing dirt after his father died, keeping one step ahead of the NPD—he’d never been arrested, never even spent the night in Nola Parish Prison, and now, in his twilight years, he just the same found himself confined. With only a rickety-ass lumpy bed, a dirty square window, a lightbulb, and a hardly working little radio to keep him company.

Deacon pressed his hands against his face and, for just a moment, allowed himself to feel the weight of years and years of living. From time to time he did this to remind himself that he was still alive and that time still passed. He found the ache and the tiredness oddly comforting.

He wasn’t sure how long he’d been sitting this way when, out of the corner of his eye, Deacon saw the overhead light flicker off. Deacon’s hands dropped into his lap as a viscous darkness filled the cell. He sighed deeply, but he didn’t rise or recoil. Where would he go? The ceiling was so low that his only choices were to sit here and see what was what or lie down and stare at the ceiling.

The darkness pulsed like the beat of a baleful heart, and something in it coalesced into a more-or-less human shape. Deacon sensed a tension in it, a wriggling motion, as if the darkness had to work to hold on to itself and that the effort made it very angry. A single bloodshot eye swam open, and its gaze fell heavy on Deacon’s forehead. He looked the dark figure up and down. Must be mighty inconvenient, not having no legs.

Silence stretched to fill the room, and Deacon waited for the apparition to break it.

The seconds ticked by, then he gave up the game. “All right, then,” he said. “You must be Stag’s friend he was talkin’ bout. What you want with me?”

i have questions for you deacon graves the figure whispered.

“Do ya, now?” Deacon asked. “Got me a few of my own.”

we shall trade knowledge for knowledge yes

“Aight, then,” Deacon said. “You first.”

how long have you lived in this city

“All my life. Born and raised.”

except we both know that is not the case

Deacon narrowed his eyes. “What you mean?”

Something tickled at the edge of Deacon’s memory. He sensed its importance, but it terrified him. Now was not the time to consider it consciously. He thrust the almost-thought aside.

how many birthdays have you celebrated how long has it been since you laid each of your dear wives to rest what year did you graduate primary school tell me deacon graves

“Listen, Jack, I don’t know you,” Deacon said. His voice had turned hard, and he spoke with authority. Fear was with him, but so was something else—the simple knowledge that he would not be broken. “You think you can show up like the Haint of All Haints and scare me bad enough to tell you all my bidness, but I done lived a long time. Haints don’t scare me none. I’ll answer one of your questions: I graduated from the Fisk School for Boys in 1913.”

tell me then deacon graves how long has it been since 1913 what year is it now

The question shocked him. He felt weaker now, his thoughts scattered. “It’s—what year is it? Thass all you wanna know?”

just so what is the year were you ever young when you remember your youth do you think of this life in this city or another city similar to this when you dream where are you deacon where do you go

A sick feeling settled in the pit of Deacon’s belly. He had thought he’d been doing so well—sitting in this little cell for however many days, mentally composing letters to each of his family members, including his two dead wives. When the haint had appeared, he’d been surprised by his own cool—impressed with his ability to keep it together under stress. But now, with his barrage of bizarre questions, the ghost had shattered Deacon’s composure.

“The hell you ask me that for?” Deacon demanded. “Errybody know what year it is! You know what year it is! I may be old, but I ain’t lost my marbles yet!”

my questions disturb you yes why is that

“It ain’t the questions bother me, ya dumb spook, it’s you!” Deacon shouted. “With your crazy red eye and your no-legs-havin’ ass standing in the corner. I ain’t answering no questions today. You just get the hell on and leave me be—or let me go. Let me go home. Let me go! Gotdamn!”

answer my questions and we will discuss the terms of your release

Deacon stretched out on the bed, his back to the far corner of the room and the glowering eye of the legless haint. It wasn’t so much that Deacon was in pain, or even that he was upset; it was that, suddenly, he was extraordinarily aware of his own skeleton, and now that feeling gave him no comfort. A man his age experiences more than his share of aches and pains on any given day—Deacon’s knees had been giving him trouble for years, especially after hard rains—but this wasn’t an ache. He just felt his bones. He cataloged them silently: the two small bones in his lower arm, the large bone of his left thigh, the many, many small bones of his hands and feet, and the stony segmentation of his ankles and wrists…

I’m tougher than this, he thought. Ain’t no trivia questions gonna give me fits. I’m tougher. Tougher. Tougher.

And another, quieter thought: Storm comin’.

He lay there, his head in his hands, for some time, before the weight of his captor’s ghostly stare made Deacon turn over, ready to cuss this haint the fuck out—but the room was empty. The dirty overhead light glowed weakly again, swinging slightly back and forth, making the shadows rock like backup dancers.

A tray of food lay on the floor in front of the cell door. The smell of it overwhelmed Deacon, brought a flood of saliva into his mouth. Red beans and rice, garlic bread, and even a praline. So this was Monday? The sight of the glistening hunks of smoked sausage sitting in their gravy… Deacon stared at it for a long time, watching steam rise from the bowl.

He knew he should be suspicious. Any number of things could have been done to that food… but his hunger by far outweighed his common sense. He would eat the food, lick the bowl, and then parcel the praline into chunks that he would allow himself slowly, over time, sucking on each morsel instead of chewing, to make the sweetness last.

Careful to hunch so as not to hit his head, Deacon rose from the bed and crossed to claim his meal. It was the best he’d ever had.

Lord, he thought as he spooned beans into his mouth. Please look after my grandbabies. Please make sure they all right.

Casey engaged the parking brake and sat still, watching in the rearview as the shadows of the palm trees splashed across the parking lot behind him. As he and Naddie made their way home, the city seemed as if it had expanded. It was larger and darker now, and its buildings made less sense. There was still too much graffiti out, and the shadows lay in unnatural groupings, as if conspiring together. The city was both dangerous and in danger.

“Talk to me,” Naddie said. “I know you’re going to say something crazy, but talk to me, at least.”

“I haven’t been that scared since I was little.”

“Of who? Stagger Lee?”

“Of anything,” Casey said. “Anybody. Did you hear them? There’s kids out there going up against that thing.”

“Casey.”

“Kids.”

“Case.”

“This is our city. This is our home.” Something yawned inside him. Some dark knowledge that was not quite a memory. He remembered driving, the fender of his blue LeBaron gobbling the road in a driving rain. He felt as if he’d been asked a question and he had little time left to figure out the answer.

“Casey. What are you going to do?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “But, damn it, I’m gonna do something.” He paused, staring at his hands on the steering wheel. Then, “Go inside. Pack some bags, and if I’m not home when you’re finished, go to bed. I’m going back to talk to Auntie Roux.”

Silence stretched for a moment, then, quietly, Naddie opened her door and left the car.

Storm coming.

Storm coming.

Storm—

“Okay,” Perry said. “Okay. I’ve got an idea.”

“See?” Brendy said. “What I told you? Perry fix everything!”

Perry, Peaches, and Brendy had talked over their problem for what seemed like hours, but if hours had passed, there was no evidence of it. The luminescent fog still hung thick around them, and the light had changed not one bit. Perry still smelled the ocean, but now, instead of comforting him, reminding him of a vacation he had enjoyed, the smell seemed to taunt him, saying, Take a big ole whiff, baby. This what the sea smell like! You ain’t never going there—or anywhere else—again!

From time to time, Perry would dream a dream that was beyond his understanding. Once he’d dreamed he was on a giant gas-filled airship that was also Zara’s Supermarket, and his classroom at school. His parents had manned the ship’s controls as it nosed its way through thunderheads, high above the earth. Perry ran to and fro, fussing with ropes and riggings that he realized only later would be of no use on an airship. As he worked, his parents spoke in bursts, reciting word problems like the ones he did in math class.

“Four-sevenths of the birthday cake was eaten on your birthday!” Perry’s mother called.

“Aye, aye!” Perry yelled, and ran toward a valve bigger than his head. He gripped it as hard as he could and sweat sprang out on his brow as he fought to turn it.

Before Perry could budge it, he heard his father’s voice: “Two-fifths of the one thousand parking spaces were for cars! When you went to get groceries—!”

“Yessir! Right away, sir!” And Perry went scrambling up a nearby rope ladder, knowing, even as he went, that he was falling behind. He awakened cold and sweating, feeling as if he’d missed something important. The worst thing about the dream was that Perry felt it was trying to communicate something extremely simple, in terms that the dream seemed to consider almost insultingly direct, but which Perry was still at a loss to understand. He still remembered that dream vividly, because the morning after it was the first time Perry found himself wishing he were better—smarter, wiser—than he was.

That was how he felt now as he tried to figure out his situation. How could he lead Peaches and Brendy back to the real world if he had no idea where they were to begin with? This was serious. Everyone—not just Peaches and Brendy, but all Nola—was counting on him. The pressure threatened to crush him, so Perry decided not to feel it.

After sitting cross-legged, like in school, for a terse discussion of their options, the trio found themselves losing steam. They stretched out head to head to head, staring up into the glowing nothing, and Perry suspected he might have fallen asleep for a while.

Now he clapped his hands, trying to energize himself. “Okay,” he said. “So we gotta… we gotta find Jailbird, right? We find Jailbird, and then once we done that, maybe Doctor Professor show up to come get him, and he’ll take us home.”

“Oh,” Brendy said, clearly disappointed.

“Perry, we don’t even know where we at,” Peaches said. “How would Fess?”

“Because he’s magic,” Perry said, warming to the idea. “He has magic powers.”

“Negro, you and Brendy got magic powers, and y’all don’t know shit.”

“Well—” Perry began without knowing how he would respond.

“Besides,” Peaches said. “Fess on my list.”

“On your list?” Brendy said. “Why?”

“Because he lied to us,” Perry said. It was the first time he’d allowed the thought to form fully in his mind. “He lied about Stagger Lee. He sent us out to catch his songs without telling us about the worst one of all.”

“Stagger Lee,” Brendy said.

“Stagger Lee,” Perry said with a nod. “Fess damnear got us killed. And he did get Peaches burned.”

“Musta been some kind of mistake,” Brendy said. “Doctor Professor wouldn’t do that.”

“No mistake,” Peaches said. “We gonna have us a conversation, me and him.”

“So finding Jailbird won’t work,” Perry said. “Damn.” He raised his arms and let them flop back down at his sides.

“Well, I don’t know,” Brendy said. “Maybe I should ask Billy to find Perry’s sack again.”

Much earlier in their discussion, before Brendy dismissed him, she had commanded Billy to find Perry’s Clackin’ Sack. The spirit had zipped around and around, spouting increasingly frantic gabble, then seemed to tire himself out. He stopped looking like Brendy altogether and became a pillar of smoke. The smoke seemed to have fire inside it, and the fire burned hotter and hotter until Brendy told Billy to go back into the rock and get some rest.

Perry’d had no idea what the limits of Billy’s powers were, but he had been certain Brendy’s command would get them home. If the spirit could force fire to burn backwards, to unburn Peaches, why wouldn’t he be able to transport them from place to place? Perry’s mother seemed to think the rock was pretty powerful—but then, she herself had admitted she knew nearly nothing about it.

So it heals people, Perry thought, but it can’t take people from place to place… That still didn’t seem to make sense. After all, hadn’t Billy drawn Perry bodily up out of the water and over to Brendy to save him from drowning? But that had been only a few feet…?

“Brendy,” Perry said. “That water I was in. How far away was it?”

“I dunno,” Brendy said. “I could hear it, but I couldn’t see no water.”

Well, that was no help. Maybe Perry could go back to sleep and dream a solution to their predicament. The idea was not entirely unattractive, but Perry felt more awake than he ever had. Alert and starved for stimulation. Maybe Billy could put him to sleep, or…

No. Think. What happened?

Perry put himself back in the Velvet Room, locking eyes with Stagger Lee.

“You,” he had said. “It was you.”

Then: “Perilous Graves. Clickety-clack, get into my sack.”

And then the world had gone away.

… Unless the world hadn’t gone away at all.

“I know why Billy got tired,” Perry said abruptly. He realized only after he’d spoken that Peaches and Brendy had been talking together, and now they shut right up.

“The world didn’t go away. We did.” A feeling of relief came over him. The sensation was so profound it felt like an invisible hand lying softly atop him, pressing him into the ground. He imagined himself sinking into the soil, down and down, at peace. A slow grin spread across his face.

“Well?” Peaches said impatiently.

“Man,” Perry said. “I was really worried for a minute there. And we gotta apologize to Billy. He started going crazy because he knows where we at.”

“Where?” Brendy said.

“Negro, spit it out!” Peaches said.

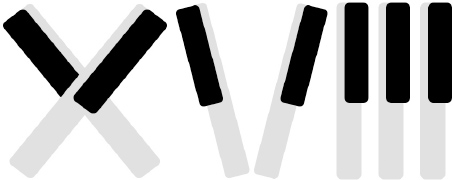

The more Perry spoke, the more certain he was that he’d guessed correctly. “Well,” he said. “I’ll show you: Brendy Graves. Peaches Lavelle. Perry Graves. Clickety-clack, get outta my sack.”