THE MOST DANGEROUS BEAST THE GRIZZLY, THE GREAT PLAINS, AND THE WEST

5

Wednesday 11 Sept. 1805. a beautiful pleasant morning. . . . passed a tree on which was a nomber of Shapes drawn on it with paint by the natives. a white bear Skin hung on the Same tree. we Supose this to be a place of worship among them.

—Joseph Whitehouse

In 1874, on a steamer heading up the Missouri River in Montana Territory, a western artist and illustrator named William de la Montagne Cary witnessed a scene one bright morning that he never forgot. From the boat deck, through good, sharp field glasses, Cary and his companions for several minutes watched a drama unfold that transfixed them with a chill Cary could not shake off: “about a mile off an immense grizzly bear [was] making for a cotton wood miles away and behind the bear came two men superbly mounted, armed to the teeth. . . . We could see distinctly the horses straining every muscle to overtake the bear who was equally anxious and making every effort to escape his pursuers.”

On the American Serengeti of the last century, this was a sight of sights, and as an artist of the West, Cary well knew it. What he was seeing ranked with western spectacles like buffalo stampedes, prairie wildfires, or cavalry or Indian charges, and for the same reason: all implied furious activity with mortal outcomes at stake. But what required buffalo in mass numbers to effect, a grizzly bear—even one running for its very life—could evoke solitaire, and that was what transfixed Cary and his companions. The grizzly was then—and still is—the historic Great Plains counterpart to the lion or leopard of the Masai Mara or the striped tiger of the steamy jungles of the Bengal: the largest and most powerful creature of the landmass, fully capable of killing humans, fully capable under certain unusual conditions of consuming humans, too. In Cary’s time on the plains most Americans were still hunters—George Armstrong Custer took time off from chasing Indians to shoot a grizzly in South Dakota that same summer—but in the nineteenth century we still understood that we had been prey almost as much as we’d been predators. Naturally we look especially closely and with a certain primal dread at any animal that might configure us as a meal. And especially so at an animal like a bear that is so much more human-like in its attack than big cats or sharks.

Even at a distance, William de la Montagne Cary felt the adrenaline of that kind of genetic memory, but he clearly also felt a sympathy for the bear as it crashed across the prairie fleeing its pursuers. The artist was one of a legion of nineteenth-century disciples of James Fenimore Cooper, and with two friends had first made a trip up the Missouri River in 1861. Returning home with sketches and some paintings, he’d gone on to become a magazine and newspaper illustrator in New York, working for publications like Scribner’s and Harper’s Weekly. These assignments had sent him into the Northern Plains again in 1874, this time to Fort Benton. The grizzly encounter was one of the high points of his trip, and—imagining the end result of the chase—he ended up executing a beautiful oil painting of what he believed the outcome might have been. Variously titled Cattle Men Tracing Grizzly to Den or Mother Bear Guarding Cubs, it became the prize piece of the artist’s exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History in New York in 1917. No less than the famous writer/conservationist George Bird Grinnell wrote the accompanying text for the exhibit. By 1917, Grinnell wrote, far from being the aggressive giant carnivores of the early wilderness West, grizzlies “have become the shyest of game and are well-nigh extinct.” Somehow, in barely more than a century, the West’s most imposing creature stood at the very brink of disappearing. On the Great Plains by 1917, the setting where the reading world had first imagined Ursus arctos horribilis, the giant bears were entirely extirpated.

How we react to animals is in part primate hard-wiring. The thump in the dark, the start to full waking, the pounding heart can transport us back to our African origins in a fraction of a second. But mostly what we think when “bear” comes to mind emerges from the tangled mess of software programs that is culture. What we’ve heard, what we’ve read, what we’ve inferred, what others have implied, for some of us what we’ve experienced—all these and other ways of absorbing information—go into creating a construction in our minds like “bear.” When an Idaho governor publicly opposed recovering grizzly bears in the Bitterroot Mountains at the turn of the twenty-first century because he said he didn’t want “massive, flesh-eating carnivores” in Idaho, the bear he imagined was a very specific kind of historical memory. But many other kinds of bears look back at us, a maddening but fascinating aspect of the world.

The grizzly inherited the mantle of most fearsome animal of the American Serengeti from the short-faced bear, which became extinct during the late Pleistocene. Dan Flores photo.

Fascinating is the right word. It’s hard to characterize the history of the grizzly bear in America in any other way, really. There is the grizzly bear out there in nature, the king of beasts in North America (at least once the truly fearsome short-faced bears and steppe lions went extinct), but a bear existing in a bear’s world. And then there is the bear in the mirror, the bear that humans see when we look at grizzlies through the lenses of our minds and cultures.

The future predicts a vanishing act for the grizzly, now confined in the contiguous United States to just two small pockets in dense mountains near Glacier and Yellowstone parks in the Northern Rocky Mountains. A few years ago a friend and I crossed the Flathead River as early in the summer as it was possible to wade across it with backpacks (which was August) and then spent a week traversing Glacier Park from its western to its eastern boundary. We hiked up a stream called Nyack Creek to the Continental Divide, through country with one of the densest grizzly populations in America, the whole way ruminating about how much edginess, how much sheer adrenaline, this Glacier landscape would lose without big bears in it. That scenario is not difficult to imagine, because out east of Glacier, the Great Plains from Alberta to West Texas was once the domain of America’s kingly bears and today harbors not a single grizzly. I have backpacked many times in the Great Plains. Those expe-riences weren’t remotely like pushing through neck-high thimbleberry bushes up Nyack Creek, with piles of fresh grizzly scat still steaming in the trail.

How was it that the grizzly once thrived and was widespread across the Great Plains when in our own time only a few hundred bears exist only in national parks deep in the mountains? The answer is a variation on a too-common story here, with one very big difference. Pronghorns and coyotes are plains survivors in our time, and re-wilding the future Great Plains may be possible to some extent even with gray wolves and bison. But judging by the difficulty we’ve had getting new populations of grizzlies going even in other Rocky Mountain locations, restoring grizzlies to the Great Plains appears to be the longest of long shots. Almost all we can do in this instance is recall the bear’s past, one not very distant in time but now growing ever fainter in the imagination, and reflect on how it all happened. At least we can do that much with grizzly bears, whereas with steppe lions, mammoths, camels, long-legged hunting hyenas, gazing across a rolling Great Plains landscape and trying to re-create in mind’s eye what it must have been like, even dreams fail.

There must have been a powerful cultural psychology at work in nineteenth-century America, a Freudian feedback loop with respect to the continent. North America’s wildness produced enough unease about the thinness of civilization’s veneer that we reacted with a numb, almost instinctive orgy of destruction aimed at the animals that embodied the wild continent. “Nonhuman nature,” writer D. H. Lawrence once wrote, “is the outward and visible expression of the mystery that confronts us when we look into the depths of our own being.” For much of American history that exercise, when we’ve indulged it, has not pleased us, producing a self-hatred that we’ve deflected outward. As another writer who sought to understand our relationship with nature, Paul Shepard, put it in one of his last books, “By disdaining the beast in us, we grow away from the world instead of into it.” That line stands as an evocative summary of much of the history of the American Great Plains.

A few representative human/grizzly stories from Great Plains history may help to reconstruct the way Americans reacted to the West’s king of beasts. The bears of our evolving historical imagination have arguably been more important to what has happened to the grizzly—and what might happen to the grizzly in the future—than the flesh-and-blood bears in the real West. History doesn’t allow for re-dos, but if it’s true that the great bear was in some significant part a creation of our cultural imaginations, was there perhaps a way out, a path not taken? Perhaps a path we might still consider so that humans and the most formidable and awe-inspiring big animal on the continent can co-exist, even if uneasily, and even if elsewhere than on the plains?

Maybe. Grizzlies are obviously a special case. But fear, respect, even morbid fascination ought not be allowed to stand as reasons for outright eradication of an animal that defined a whole ecoregion. Perhaps we should start with American stories about grizzly bears, stories that explain why, from an estimated continental population of 100,000 grizzly bears five centuries ago, from Alaska southward into Mexico and across the entire Great Plains as far east as Kansas, today fewer than 1,000 grizzlies are left in the Lower Forty-Eight, none of them on the plains. In laying out these stories I have no intention of ignoring other ways, Indian ways, for example, of “seeing” bears. But I’d like to consider those other, older ways of understanding bears not so much as a starting point from which we’ve traveled, but instead as a potential destination.

Despite a scattering of encounters with grizzly bears as early as the seventeenth century, for two centuries after Europeans settled the continent, grizzly bears were little known to folk knowledge and only existed as rumors in the scientific grasp of North America. The first known description of grizzlies we have by a European was left by Spanish explorer Sebastian Viscaino in the year 1602. Sailing along California’s Central Coast, in the bay where Monterrey and Carmel (and Pebble Beach) would one day stand, two centuries before the Lewis and Clark expedition would bring “white bears” to the attention of Enlightenment science, Viscaino watched grizzlies clamoring with astonishing nimbleness over the carcass of a whale washed up on a Monterrey Bay beach. Almost a century later, in 1690 and far, far inland, a Hudson’s Bay Indian trader named Henry Kelsey was traveling overland on the grassy yellow plains of Saskatchewan when his party encountered a grizzly. This was not a view from the safety of a sailing vessel, but face-to-face on the ground, and Kelsey’s first reaction was to shoot. He thus became the first European of record to kill a grizzly bear, an event pregnant with portents for the future of bears and of the Great Plains. Kelsey’s act greatly alarmed his Indian companions, who warned him that he had struck down “a god.”

Other unknown Russian, English, and American traders along the Pacific Coast no doubt encountered grizzlies by 1800, and the Spaniards in California and New Mexico and French traders penetrating the plains certainly had experiences with grizzlies by then. But at the beginning of the nineteenth century, journal-keeping Anglo-Americans began to push by boat and on foot into grizzly country. Archaeology and paleontology since have established firmly that the entire western half of North America, including the river corridors spilling from the Rockies out across the Great Plains, and even the island stepping-stone mountain ranges of the Southwest, was all grizzly country then. Except for Santa Fe and Taos and the Spanish missions along the Pacific Coast, no European settlements lay within this immense sweep of country. In 1800 it was inhabited by perhaps 2 million Indians, 25–30 million buffalo in times of good weather, and perhaps 50,000–60,000 grizzlies. So many grizzlies, indeed, that Ernest Thompson Seton says Spanish travelers along the rivers of Northern California could easily see 30–40 grizzlies in a single day.

Biologists believe grizzlies were far out on the Great Plains because there were bison to scavenge there, so as soon as Americans reached the buffalo country, they were in grizzly country, too. Although not the first Americans to encounter grizzly bears, Lewis and Clark occupy a prominent place in this story, in good part because they stand as such an obvious cultural template for this country’s reaction to an animal so formidable.

American attitudes toward wildlife like bears by the Jeffersonian Age were complex and deeply internalized across thousands of years of human history. Genetic programming from as far back as the Paleolithic obviously preserves a human memory of giant bears. Mammals of the Northern Hemisphere, they would have been a new thing for modern humans migrating out of Africa and into Europe and Asia 45,000 years ago. Our Neanderthal ancestors would have long since been familiar with bears, but our own species likely first confronted them in southern Europe. Among the oldest painted art locales anywhere in the world, the walls of Chauvet Cave in the Ardeche Valley of southern France preserve images that may be 37,000 years old. The large paintings here breathtakingly represent cave bears along with bison, horses, rhinos, lions, mammoths, and ibex. Indeed, Chauvet Cave was a cave bear den. When spelunkers discovered the site in 1994, the Chauvet floor preserved bear skeletons, bear footprints that looked days old, and a cave bear skull the ancient artists had placed atop a boulder as a kind of shrine. Cave bears were formidable beasts as large or larger than grizzlies.

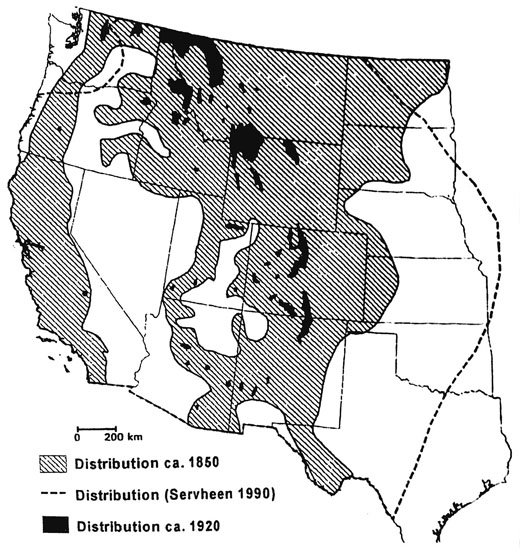

The grizzly’s original range extended as far out onto the Great Plains as the Dakotas, Kansas, and Texas, where they scavenged bison carcasses up and down the American Serengeti. From Conservation Biology, August 2002.

As for North America’s own Pleistocene bear, the gracile and active short-faced bear, the Canadian biologist Valerius Geist believes that until it went extinct 14,000 years ago, this super-aggressive bear may have single-handedly kept humans from migrating across the Bering land bridge in America.

Atop such a long-standing animus, whose outlines are sketchy but in pagan Europe indicate that bears once served as both totems and gods, later traditions like Judaism and Christianity, and eventually the scientific way of understanding the world, layered on a very complex cultural matrix about bears for Europeans. Almost all these strands are evident in the Lewis and Clark encounters, which were so widely read in early America that they became a kind of nineteenth-century guidebook to how to think about the West, its Indians, and its wildlife.

Jefferson’s explorers had heard before they ever left the East Coast about the possible presence of a bear in the West that was different from the well-known black bear. Wintering at the Mandan villages in 1804–1805 they got exposed to more direct evidence by the Indians. Indeed, they had already seen the tracks of a “white bear” in eastern South Dakota, where some of the hunters claimed to have wounded one. But Lewis and Clark’s firsthand experiences with grizzlies actually began in April 1805, in present Mountrail County, North Dakota, about halfway between Minot and Williston.

According to the University of Nebraska’s new edition of the Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, edited by Gary Moulton, this is how Americans and grizzly bears interacted for the first time on the Great Plains:

April 13, 1805: [Lewis]. we found a number of carcases of the Buffaloe lying along shore, which had been drowned by falling through the ice in winter an lodged on shore by the high water. . . . we saw also many tracks of the white bear of enormous size, along the river shore and about the carcases of the Buffaloe, on which I presume they feed. we have not as yet seen one of these anamals, tho’ their tracks are so abundant and recent. the men as well as ourselves are anxious to meet with some of these bear. the Indians give a very formidable account of the strengh and ferocity of this anamal, which they never dare to attack but in parties of six eight or ten persons; and are even then frequently defeated with the loss of one or more of their party. the savages attack this anamal with their bows and arrows and the indifferent guns with which the traders furnish them, with these they shoot with such uncertainty and at so short a distance, unless shot thro’ head or heart wound not mortal that they frequently mis their aim & fall sacrefice to the bear. two Minetaries were killed during the last winter in an attack on a white bear. this anamal is said more frequently to attack a man on meeting with him, than to flee from him. When the Indians are about to go in quest of the white bear, previous to their departure, they paint themselves and perform all those supersticious rights commonly observed when they are about to make war uppon a neighboring nation.

Over the next few days, as the party traced the Missouri across North Dakota towards the present Montana border, grizzlies continued to tease their imaginations. On April 14, Clark wrote in his journal that they had at last seen “two white bear running from the report of Capt. Lewis Shot, those animals assended those Steep hills with Supprising ease & verlocity.” On the 17th Lewis was moved to write that although they “continue to see many tracks of the bear we have seen but very few of them, and those are at a great distance generally runing from us . . . the Indian account of them dose not corrispond with our experience so far.”

The party’s first real encounter came on the morning of April 29, 1805, in what is now either Roosevelt or Richland County, near the far eastern Montana town of Wolf Point. Lewis describes their mounting adventures this way:

I walked on shore with one man. about 8 A. M. we fell in with two brown or (yellow) bear; both of which we wounded; one of them made his escape, the other after my firing on him pursued me seventy or eight yards, but fortunately had been so badly wounded that he was unable to pursue so closely as to prevent my charging my gun; we again repeated our fir and killed him. it was a male not fully grown, we estimated his weight at 300 lbs. . . . The legs of this bear are somewhat longer than those of the black, as are it’s tallons and tusks incomparably larger and longer. . . . it’s colour is yellowish brown, the eyes small, black, and piercing . . . the fur is finer thicker and deeper than that of the black bear. these are all the particulars in which this anamal appeared to me to differ from the black bear; it is a much more furious and formidable anamal, and will frequently pursue the hunter when wounded. it is asstonishing to see the wounds they will bear before they can be put to death. the Indians may well fear this anamal equiped as they generally are with their bows and arrows or indifferent fuzees, but in the hands of skilled riflemen they are by no means as formidable or dangerous as they have been represented.

That optimistic arrogance, so classically American, coupled with a typical national faith in scientific technology’s ability to prevail where the tools of lesser cultures left them vulnerable, weren’t destined to last. On May 5, 1805, in present McCone County, Montana, the American explorers were given considerable pause when they had their first encounter with a full-grown grizzly bear. Again, let Meriwether Lewis tell the story:

Capt. Clark and Drewyer killed the largest brown bear this evening which we have yet seen. it was a most tremendious looking anamal, and extremely hard to kill notwithstanding he had five balls through his lungs and five others in various parts he swam more than half the distance acoss the river to a sandbar & it was at least twenty minutes before he died; he did not attempt to attact, but fled and made the most tremendous roaring from the moment he was shot. We had no means of weighing this monster; Capt. Clark thought he would weigh 500 lbs. . . . this bear differs from the common black bear in several respects . . . the heart particularly was as large as that of a large Ox. his maw was also ten times the size of the black bear, and was filled with flesh and fish.

In his own journal, Clark called this bear “a Brown or Grisley beare” and “the largest of the Carnivorous kind I ever Saw.” Lewis noted that after campfire discussion that night:

I find that the curiossity of our party is pretty well satisfyed with rispect to this anamal, the formidable appearance of the male bear killed on the 5th added to the difficulty with which they die when even shot through the vital parts, has staggered the resolution several of them, others however seem keen for action with the bear; I expect these gentlemen will give us some amusement shortly as they soon begin now to coppolate.

Six days later, on May 11, having passed the mouth of the Milk River—which some biologists of pre-Columbian America believe was a kind of epicenter of grizzly bear range and numbers on the Great Plains, perhaps because it had long been in a buffer zone between warring groups like the Blackfeet, Shoshones, and Mandans where Indian hunting parties seldom ranged—the party had an experience that cemented the evolution in attitudes that was taking place. Once again, let’s let Lewis describe it:

About 5 P.M. my attention was struck by one of the Party runing at a distance towards us and making signs and hollowing as if in distress . . . he arrived so much out of breath that it was several minutes before he could tell what had happened; at length he informed me that in the woody bottom on the Lard side about 1 1/2 [miles] below us he had shot a brown bear which immediately turned on him and pursued him a considerable distance but he had wounded it so badly that it could not overtake him; I immediately turned out with seven of the party in quest of this monster, we at length found his trale and persued him about a mile by the blood through very thick brush of rosebushes and the large leafed willow; we finally found him concealed in some very thick brush and shot him through the skull with two balls . . . it was a monstrous beast . . . we now found that Bratton had shot him through the center of the lungs, notwithstanding which he had pursued him near half a mile and had returned more than double that distance and with his tallons had prepared himself a bed in the earth . . . and was perfectly alive when we found him which could not have been less than 2 hours after he received the wound; these bear being so hard to die reather intimedates us all; I must confess that I do not like the gentlemen and had reather fight two Indians than one bear; there is no other chance to conquer them by a single shot but by shooting them through the brains.

This initial American confrontation with the largest predator on the continent continued to worsen, primarily because the members of the party seem not to have learned the rather obvious lesson, and kept on shooting grizzlies. On the 14th six hunters spotted a grizzly on open ground and went after him, approaching to within forty yards. According to Lewis:

two of them reserved their fires as had been previously conscerted, the four others fired nearly at the same time and put each his bullet through him, two of the balls passed through the bulk of both lobes of his lungs, in an instant this monster ran at them with open mouth . . . the men unable to reload their guns took flight, the bear pursued and had very nearly overtaken them before they reached the river . . . [they] concealed themselves among the willows, reloaded their pieces, each discharged his piece at him as they had an opportunity they struck him several times again but the guns served only to direct the bear to them, in this manner he pursued two of them seperately so close that they were obliged to throw aside their guns and pouches and throw themselves into the rivr altho’ the bank was nearly twenty feet perpindicular; so enraged was this anamal that he plunged into the river only a few feet behind the second man . . . when one of those who still remained on shore shot him through the head and finally killed him . . . they found eight balls had passed through him in different directions.

Absorbing the mounting tension of these journal entries almost two centuries later, a modern reader almost has to be restrained to keep from shouting aloud at Meriwether Lewis, “For God’s sake, order them to stop shooting up grizzly bears going about their own goddamned business!”

Of course no one except the Indians thought to stop shooting up grizzlies for a very long time to come. A twenty-first century American has to pose the question—why, once they’d collected specimens for science, did Lewis and Clark and other nineteenth-century Americans feel such a compulsion to react to animals in the West by shooting them? What had history lodged in the American psyche that made the left-and-right, wholesale slaughter of animals—more than 500 million of them is Barry Lopez’s estimate, although no one can ever know—such a part of the history of the West, and especially of the grand grasslands of the Great Plains? Why, for example, would the US Army officer and popular writer Colonel Richard Dodge, along with his four companions, feel it a worthy expenditure of their time to slaughter, in three weeks of lounging about on New Mexico’s Cimarron River, 127 buffalos, 13 deer and pronghorns, 154 turkeys, 420 waterfowl, 187 quail, 129 plovers and snipe, assorted herons, cranes, hawks, owls, badgers, raccoons, and even 143 songbirds? According to Dodge’s obsessively kept scorecard, that was a total of 1,262 animals, many of which had functioned only as convenient live targets for bloodlust.

It’s a hard thing to know the history of the Great Plains and not pose that question. The Lewis and Clark response seemed ubiquitous everywhere one looks. Once I hiked to an Indian rock art panel on the Texas plains where Comanches or Kiowas had portrayed a wagon train with virtually every stick figure traveler brandishing a gun, the sandstone wall carved with jagged, lightning-like lines going in every direction and in such profusion it was clear the artist was attempting to convey a party firing in every direction as the wagons rolled along. Accidental wounds from gunfire, along with drownings during stream crossings, in fact were the principal causes of mortality on the western emigrant trails. But the bigger question: why did we so consistently look at the West through the sights of a rifle?

These initial Lewis and Clark encounters with Great Plains grizzly bears may give us some clues as to why that was. Some of the reasons seem so deeply internalized that virtually the only way we are able to recognize that they aren’t universal is to contrast American attitudes towards animals with those of other cultures. At least since the time of the Greeks, and the notion was broadly disseminated through all classes of Western culture by Judeo-Christian traditions, Western Europeans had absorbed the idea that humans were the true measure of the divine on earth, the only one of God’s creations made in His image, the only ones possessing that abstract, immortal animation known as a soul. According to Genesis 1:28, God had created animals solely for the benefit of humans, for humans to do with as they would. Over that basic idea, the Scientific Revolution of the Age of Reason had layered Descartes’s assumptions that, lacking souls or sentience, animals were little more than automatons, living machines with no capacity for self-awareness, not even the capacity to experience injury.

These were fictions that anyone who shot a grizzly and heard it roar its rage and pain—think of the Montana grizzly the Lewis and Clark party shot on May 5 that made no attempt to attack its persecutors but swam to a sandbar “and made the most tremendous roaring from the moment he was shot”—ought to have questioned. But few did. By the Jeffersonian Age, for many Americans individual animals were less teachers of universal truths about being human than they were target practice. Or specimens collected for dispassionate scientific study. Or fiends that represented a danger to civilization and its apparently shaky veneer. Or, worthy opponents against which to pit one’s woodscraft, daring, and skills in contests of status.

And as tests of one’s technology. Lewis and Clark are exemplars of yet another Western notion that is evident from reading their journals about grizzly encounters, and that is a faith in technology, and the peculiar temptation to test technology’s outer limits on what they regarded as challenging and dangerous phenomena. Their grizzly accounts feature a repeated disbelief that the continent held an animal so powerful and tenacious of the will to live that a mere animal could come close to overwhelming American scientific technology. It’s the theme Herman Melville explored in Moby Dick, wherein nature in the form of a great and dangerous beast drives an American puritan to madness when he can’t subdue it.

Lewis and Clark’s accounts were not the only ones that filtered in from the West about the grizzly bear, of course. One of the ones that the compilations of bear stories routinely miss was one from the Southern High Plains, a story that passed by word-of-mouth back to places like my home state of Louisiana, perhaps even inculcating the legendary bear killer Ben Lilly with the idea that grizzly bears were the very minions of the devil, and that all of them deserved speedy death at his hands. I am talking now about the story of the first recorded death at a grizzly’s hands on the Southern Great Plains.

It was 1821 when this encounter with a grizzly took place on what was christened “White Bear Crick,” now known as the Purgatory River out on the plains southeast of Pike’s Peak, Colorado. A group of Missouri and Louisiana traders had worked their way up the Arkansas River to trade with the Comanches, and when the cold snaps of November hit they moved towards the mountains to seek winter quarters. For many of the semi-illiterate Southern traders involved, this was their first inkling that the West held anything like a grizzly bear. I still find this account, flavorfully preserved and creatively spelled in the journal of a trader named Jacob Fowler, one of the most chilling grizzly encounters I’ve ever read, in part because of the bear’s single-minded pursuit, which no amount of distraction seemed able to deter.

Somehow it is made even more immediate and easily imagined by the frontier vernacular in which it is told. This is how Jacob Fowler related this remarkable story in the daily journal he kept.

13th novr 1821 tusday: Went to the Highest of the mounds near our Camp and took the bareing of the Soposed mountain Which Stud at north 80 West all So of the River Which is West We then proceded on 2 1/2 miles to a Small Crick Crosed it and ascended a gradual Rise for about three miles to the Highest ground in the nibourhood—Wheare We Head a full vew of the mountains this must be the place Whare Pike first discovered the mountains Heare I took the bareing of two that Ware the highest. . . . Crossed [Purgatory Creek] and Camped in a grove of Bushes and timber about two miles up it from the River We maid Eleven miles West this day—We Stoped Hare about one oclock and Sent back for one Hors that Was not able to keep up—We Heare found some grapes among the brush—While Some Ware Hunting and others Cooking Some Picking grapes a gun Was fyered off and the Cry of a White Bare Was Raised We Ware all armed in an Instent and Each man Run his own Cors to look for the desperet anemel—the Brush in Which we Camped Contained from 10 to 20 acors Into Which the Bare Head Run for Shelter find[ing] Him Self Surrounded on all Sides—threw this Conl glann [Colonel Glenn] With four others atemted to Run But the Bare being In their Way and lay Close in the brush undiscovered till the[y] Ware With in a few feet of it—When it Sprung up and Caught Lewis doson [Dawson] and Pulled Him down In an Instent Conl glanns gun mised fyer or He Wold Have Releved the man But a large Slut [dog] Which belongs to the Party atacted the Bare With such fury that it left the man and persued Her a few steps in Which time the man got up and Run a few steps but Was overtaken by the bare When the Conl maid a second atempt to shoot but His [gun] mised fyer again and the Slut as before Releved the man Who Run as before—but Was Son again in the grasp of the Bare Who Semed Intent on His distruction . . . the Conl now be Came alarmed lest the Bare Wold pusue Him and Run up [a] Stooping tree—and after Him the Wounded man and [he] Was followed by the Bare and thus the[y] Ware all three up one tree . . . [but] the Bare Caught [Dawson] by one leg and drew Him back wards down the tree . . . I Was my Self down the Crick below the brush and Heard the dredfull Screems of [the] man in the Clutches of the Bare—the yelping of the Slut and the Hollowing of the men to Run in Run in the man Will be killed . . . but before I got to the place of action the Bare Was killed and [I] met the Wounded man with Robert Fowler and one or two more asisting Him to Camp Where His Wounds Ware Examined—it appeers His Head was In the Bares mouth at least twice—and that When the monster give the Crush that Was to mash themans Head it being two large for the Span of His mouth the Head Sliped out only the teeth Cutting the Skin to the bone Where Ever the[y] tuched it—so that the Skin of the Head Was Cut from about the Ears to the top in Several derections—all of Which Wounds Ware Sewed up as Well as Cold be don by men In our Situation Haveing no Surgen nor Surgical Instruments—the man Still Retained His under Standing but Said I am killed that I Heard my Skull Brake—but We Ware Willing to beleve He Was mistaken—as He Spoke Chearfully on the Subgect till In the after noon of the second day When He began to be Restless and Some What delereous—and on examening a Hole in the upper part of His Wright temple Which We beleved only Skin deep We found the Brains Workeing out—We then Soposed that He did Hear His Scull Brake He lived till a little before day on the third day after being Wounded—all Which time We lay at Camp and Buried Him as Well as our meens Wold admit Emedetely after the fattal axcident and Haveing done all We Cold for the Wounded man We turned our atention [to] the Bare and found Him a large fatt anemel We Skined Him but found the Smell of a polcat so Strong that We Cold not Eat the meat—on examening His mouth We found that three of His teeth Ware broken off near the guns [gums] Which We Sopose Was the Caus of His not killing the man at the first Bite—and the one [tooth] not Broke to be the Caus of the Hole in the Right [temple] Which killed the man at last—

Stories such as this one, circulating through the frontier towns and among the ranks of traders and trappers that became the foundation of many of the West’s later settlers, were instrumental in casting all grizzlies as fearsome brutes to be hunted down and shot to death at every opportunity. Building on Meriwether Lewis’s term, the grizzly was a “wrathful monster,” as the writer Frances Fuller Victor wrote of a Yellowstone grizzly in her 1870 book, The River of the West.

In 1991 the writers Tim Clark and Denise Casey compiled a volume they titled Tales of the Grizzly: Thirty-Nine Stories of Grizzly Bear Encounters in the Wilderness, which chronicle grizzly/human encounters in the Northern Rocky Mountains from 1804 through 1929. Their collection allowed them to chart what they decided were five distinct periods in the evolution of the American relationship with grizzly bears: (1) A Native American period, when bears were mythic figures, teachers of medicines, helpers, a species whose physiological similarity to humans offered the possibility for transmigration in both directions—a relationship with nature, Clark and Casey assert, that would have been “almost incomprehensible to most modern Americans.” (2) An Exploration/Fur Trade period, exemplified by the grizzly encounters of Lewis and Clark and Jacob Fowler, which exposed the fallacy of assumptions about human dominance and faith in technology, and created the initial impressions of grizzlies as the horrible bear, the wilderness fiend that offered Americans a reminder of the dangers of uncontrolled, chaotic nature.

Periods (3) and (4) in this chronology are the periods of conquest and settlement, when homesteaders resolved that it was a Christian duty to eradicate grizzlies and other formidable wildlife in order to liberate the wilderness for God and the Grand Old Party. During this phase, tens of thousands of grizzly bears were shot on sight, and not just to wipe them off the plains for the arrival of the livestock industry. Settlers killed 423 grizzlies in the North Cascade Mountains alone just between 1846 and 1851. In the early twentieth century the Great American War on grizzly bears featured an alliance between livestock interests and the US Biological Survey, whose hunters made official the war on wolves, coyotes, lions, and bears, in the process creating an early federal subsidy for the ranching industry in the West.

That same Progressive era witnessed the fifth period, the official rise of sport hunting and its replacement of market hunting, which now had a black eye. For the animals in the sights, of course, it wasn’t so easy to tell the difference. But many sport hunters took to heart President Theodore Roosevelt’s advice that “The most thrilling moments of an American’s hunter’s life are those in which, with every sense on the alert and with nerves strung to the highest point, he is following alone . . . the fresh and bloody footprints of an angered grisly.” For hunters, eliminating “bad animals” like predators made sense not just in terms of growing the numbers of huntable elk and deer; going after grizzlies also had become the ultimate nostalgic capture of the vanishing frontier, the hunter’s version of a Frederic Remington or Charlie Russell painting. As Roosevelt put it, tellingly, “no other triumph of American hunting can compare with the victory to be thus gained.”

Historian Matt Cantwell, in his intellectual history of hunting titled A View to Death in the Morning, unearthed an unusual Henry David Thoreau quote that speaks to a point I made earlier in this chapter: “He is blessed who is assured that the animal is dying out in him day by day.” America must have been feeling very blessed indeed by the early twentieth century as the rapturous pursuit of bears dwindled their numbers and presumably banished any subconscious fears about human nature.

I find merit in the straightforward chronology of collections like Tales of the Grizzly. But my own instinct is to extend the interpretation in at least two ways that seem important, by pursuing the evolution of ideas about bears in both directions from the early twentieth century.

First, as grizzly numbers dropped drastically in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an interesting phenomenon emerged in the way Americans began to perceive grizzlies, wolves, and occasionally even coyotes. More and more, as their numbers dwindled or as the persecution amplified, ranchers, sportsmen, and Bureau of Biological Survey hunters began to individualize particular animals of all these species and give them their own personalities and even names. Once so numerous out on the plains, grizzlies, elk, and other classic Great Plains species had now fled to the mountains. So these last bears are always secreted away up in the peaks. Among grizzlies there was the Wyoming bear known as Big Foot Wallace. There was a notorious California grizzly of the Sierra Nevada called Club-Foot, a Colorado grizzly named Old Mose, a grizzly in Idaho known as Old Ephraim, and a Greybull River bear Wyoming ranchers named Wab, whose life story, in much fictionalized form, the nature writer Ernest Thompson Seton told in his 1900 book, The Biography of a Grizzly.

By the 1890s hunters, ranchers, and the collapse of the bison herds combined to drive grizzlies off the plains and into the mountains, where they have survived only in the Northern Rockies. Dan Flores photo.

This individualization of grizzlies was an interesting development. It rested on a sentiment, clearly widespread in America at the turn of the century, which had its sources in Darwinian thought as popularized by the natural history writers of the day. Writers of the age, like Seton, Jack London, John Burroughs, Enos Mills, and John Muir, were struggling to erase the Tennyson imagery of a Darwinian world as “nature, red in tooth and claw.” The literary devices they used—the personification of animals, an emphasis on animal individuality, cooperation, intelligence and reasoning, and the device of telling their stories from the point of view of the animals (as in London’s Call of the Wild or James Oliver Curwood’s The Grizzly King) were designed in part to effect a more favorable regard for animals. Humanitarian animal reformers at the turn of the century even discussed the hitherto unimagined possibility that animals had souls; one eccentric East Coast faction went so far as to found a church to save the souls of the beasts around them. As H. W. Boynton, a critic following these trends, summarized, the message for a world distressed by the implications of Darwinism seemed to be: “If we are only a little higher than the dog, we may as well make the dog out to be as fine a fellow as possible.”

Despite the sympathetic and somewhat maudlin view of grizzlies presented in Seton’s Biography of a Grizzly (with the grizzlies of the plains badlands now long gone and his mountains filling with ranchers and tourists, aging bear Metitsi Wahb commits suicide) and in Curwood’s The Grizzly King (wherein the wounded but peace-loving grizzly lets his hunter/antagonist walk away unharmed in the end), it took the advent of the Age of Ecology seventy-five years later to begin to rescue predators from a general hatred in America. The real Wab, after all, had met a rather different end than Seton gave him. He was shot by a rancher, the fourth grizzly the hunter had killed that day.

In the minds of many scientists and wildlife managers, the individualizing of animals was long tarnished by the “nature-faker” controversies of the Seton period. With grizzlies long since wiped out on the plains, ranchers, sport, and paid federal hunters steadily extirpated grizzlies across the Mountain West—hunters killed the last grizzly in Texas, in the Davis Mountains, in 1890, the last one in California in 1922, Utah’s last big bear in 1923, Oregon’s and New Mexico’s last grizzlies in 1931, and Arizona’s last one in 1935. Professional wildlife management moved under the influence of the Murie brothers, Aldo Leopold, and Eugene Odum in the direction of ever more species-focused directions. Following their leads, the individualistic ideas inherent in the Western worldview gave way in biology to more holism, a stance more biocentric and ecosystem-oriented than before. The new biological holism, however, until recently stopped short of recognizing individuality in animals, let alone rights for individual creatures. Its realm has been the health of species as a whole, and more recently the health of ecosystems. The idea of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem emerged as a concept first applied by the famous Craighead brothers to manage Yellowstone grizzlies as a species and as components of a larger habitat.

Prior to twenty-first-century studies that have begun to recognize pronounced individuality in animals like wolves, or urban coyotes, the last noted American environmental thinker who was willing to try for a blend that respected both species and individual animals was John Muir. Between Muir and today’s biologists like Stanley Gehrt (who has become fascinated with the idea of individuality in coyotes), animal individuality was long a special target of ire by ecologists and biologists. Although individuality is genetically logical, readily observable in animals in virtually any context, and in fact enjoys practical application in the treatment of “problem” bears and wolves, lingering reluctance about embracing the individual rather than the species seems to spring from the unsavory historical association it has with early twentieth-century nature-faking. Second, and if anything even more frightening to some, animal individuality plays into the arguments of the animal rights groups. Contemporary animal advocates assert an apparently radical doctrine: that individual animals have rights, and that the circle of ethical treatment—which in the Western tradition has expanded through history to confer rights to individuals of groups once denied legal standing, such as women, Native Americans, African Americans, now gay and transgender people—must and ought to be extended to animals on an individual basis.

Earlier in this chapter I mentioned a path not taken, and in closing I’d like to return to that theme. If we are serious about preserving not just the 1,000 grizzlies now left to us, but biodiversity of all kinds in future America, there may be some merit in reconsidering the concept of animal individuality and even analyzing how individual animal rights might be conferred. I cannot say that traditional history stands behind this assertion, because the writers of traditional American history have always assumed that wild animals, especially, are little more than “resources” and often simply wildlands obstacles that inevitably had to give way to progress. A history that judges as individuals those “monster bears” that Meriwether Lewis and Jacob Fowler described—bears whose home territories explorers and traders had entered and that certainly deserved better than being shot on sight as a test of technology and manhood—might go farther towards awakening our environmental conscience than thinking of them as species, resources, obstacles, or even components of an ecosystem.

Of course I fully recognize the logical and practical problems involved in going from writing history this way to conferring actual legal standing and managing this way. But reading about Native American mythologies, imagery, and rituals associated with bears, you have to be struck by the possibilities that such thinking offers. Maybe the reason there were still 100,000 grizzlies even after 15,000 years of the Indian presence of America was because, as Meriwether Lewis asserted, Indian technology was not up to the task of getting rid of them, although you have to note in this regard that Columbian mammoths were pretty formidable, too, yet the Clovis people apparently still managed to push them into extinction.

All the same, without trying to appropriate anyone’s culture or romanticize anyone’s past, it is difficult not to conclude that a way of thinking that recognized bears as essentially humans in another form, thus conferred individuality to bears, and thus a corpus of rights to bears—among them the simple right to exist—must have played some role in the historical fact that more than 5 million people and 100,000 bears were able to live together in America for so long. I’m intrigued that Indian grizzly stories do not whitewash bears. The bear personalities in stories from the Blackfeet to the Nez Perce to the Kiowas are complex ones. Almost always the bears possess traits valuable to humans; one Indian culture after another thought of grizzlies as teachers of medicines and herb knowledge, as in a Blackfeet story called the “Friendly Medicine Grizzly.” At other times, as in a Gros Ventres story of how the Big Dipper appeared in the sky, grizzlies are “monsters” that lay rapacious waste to human communities and literally chase people into the heavens.

Consistently, though, as in the lusty Athabaskan story “The Girl Who Married the Bear,” or the male anxiety tale from the Nez Perce called “The Bear Woman with a Snapping Vagina,” the bears are individuals. They are both good and evil, are valued and respected in either event on an individual basis, and their inherent right to exist is never an issue. In the Indian stories about bears, bears and humans mirror one another. Indeed, one of the most constant themes is that humans and bears play interchangeable roles.

The historical arc of the great bear’s story over the five centuries since Europeans arrived is far less nuanced and has a crystal clear direction. Something about the way Americans have thought about bears has been catastrophic to the grizzly, which has undergone a hundredfold reduction in numbers and has entirely disappeared from the core of its ancient range on the Great Plains. Yet in truth there is little that is completely inevitable about history. So we ought not be content that a perspective on bears like that of the natives of the continent is either “incomprehensible” or “too alien.” A biologist might say that the bears in the Indian stories are anthropomorphs. Modern nature writers like Bill McKibben will no doubt insist that we have so separated ourselves from the natural world and “humanized” the wild that nature itself is dead and there is no longer a path home. Some historians may continue to write about animals without questioning the assumptions of human dominance. And grizzly bears may never rear up out of a willow thicket on the Great Plains again. All that may happen, and perhaps will. But none of it is inevitable.

A few years ago—it was early August of 2009—a group of us spent five days backpacking into the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana. The Bob is a place where the blocky limestone ridges of Montana’s Rocky Mountain Front drop away to the plains, to yellow grasslands that roll away, as they always have done, nearly 500 miles east. There had been days of rain before we got into the mountains, and within a couple of miles of the trailhead we began to notice not only wolf tracks on the trail but as well the prints of a gigantic grizzly bear, splayed out in the mud like impact craters on a distant planet. What particularly caught our attention as we hiked in was that the bear tracks were headed out, towards the plains.

A week after we got out of the mountains, back in Missoula the local paper carried a headline that shocked all of us. Later on the very day we had hiked out to our cars in the morning, a Forest Service ranger had found an immense male grizzly shot dead and left to rot less than a mile out into the plains. And it was not just any bear. Biologists and rangers had known this particular bear for more than a decade. They had named him “Maximus” because of his extraordinary size; he’d stood 7½ feet tall and weighed 800 pounds. Biologists were certain he was the biggest grizzly in Montana. But what most characterized this bear was his admirable behavior. He was “a good bear,” a grizzly that had never gotten in any trouble at all, had left stock alone, retreated into the woods when hikers passed, and ignored their camps. All he was doing was going on a walkabout into the prairies, which made him visible. And got him shot.

A respectful wild grizzly who knew how to live among us deserves a better fate than this. And so do we.