LOVING THE PLAINS, HATING THE PLAINS, RE-WILDING THE PLAINS

8

And what a splendid contemplation too, when one (who has traveled these realms, and can duly appreciate them) imagines them as they might in future be seen (by some great protecting policy of government) preserved in their pristine beauty and wildness, in a magnificent park.

—George Catlin, on the Missouri River, 1832

The vanishing prairie is as worth preserving for the wilderness idea as the alpine forests.

—Wallace Stegner, “The Wilderness Letter”

I know almost nothing useful about W. H. Auden, the twentieth-century British writer-critic, except that once he wrote these lines, which I committed to memory: “I cannot see a plain without a shudder—‘Oh God, please, please, don’t ever make me live there!’” There’s an exclamation point at the end of that sentence. Auden’s sentiment, I think—and most modern Americans I feel sure would agree with it—captures the early twenty-first-century view of the matter nicely. The Great Plains is not, by any standard measure of aesthetics, an admired part of America these days, a loved landscape of our contemporary times the way we love the mountains or the oceans or even the deserts. As even Deborah Epstein Popper, a proponent of a future Buffalo Commons on the plains remarked during a tour of the Southern Plains of Oklahoma and Texas in the early 1990s: “This is terrible country! . . . There is nothing here. It is un-country. It shouldn’t be allowed to exist!”

Anyone who has driven an automobile across the country Popper is describing recognizes her feeling. Through the car windows a vast emptiness of space assaults the senses. The horizon encircles the world like the rim of an immense plate, and no matter how fast you drive it recedes in front of you, eventually placing you in a kind of Twilight Zone of suspended forward motion. The wind buffets and rocks your car. There are stretches where, if you roll down the windows, the country smells like a dustier Iowa, with more than a hint of ammonia, feedlots, and hog farms. Other than the frequent sight, oddly in these sere expanses, of thousands of waterfowl threading the blue bowl overhead, you see virtually no wildlife—maybe a few pronghorns if you look really hard, more likely a coyote rocking across the road. You probably don’t see a single prairie dog. Much of the day the harsh light is almost too bright to look at, or at least it is when the light isn’t diffused into a brown pall by agriculture going airborne. Tiny burgs memorable for the amount of windblown waste snagged on chainmesh fences loom and recede along laser-straight highways. Billboards unintentionally advertising the plains social order—Jesus, cowboy boots, farm machinery, banking loans, pesticides, the Denver Broncos—actually become welcome breaks in the monotony. A pervading notion characterizes such drives: “I wish to God I’d have flown.”

So we react to the modern world of the Great Plains. But it was not always so. There was a time not so long ago when the reactions were very different. To stoke our sense of wonder at the variability of human response to place, let me quote a few of them. They are about the same place I just described, and that is a remarkable thing.

The first is from Sir William Dunbar, a Scottish scientist from Natchez, Mississippi, whom President Thomas Jefferson engaged to help him lead what would have been the first American exploration into the heart of the Southern Plains. Situated as he was on the forested edges of fascination with the country farther west, Dunbar re-created for Jefferson the sense of excitement western travelers had about the Great Plains two centuries ago.

“By the expression plains, or prairies,” he told the president, “it is not to be understood a dead flat without any eminences.” He went on: “The western prairies are very different; the expression signifies only a country without timber. These prairies are neither flat nor hilly, but undulating in gently swelling lawns, and expanding into spacious valleys.” Dunbar had not been into the interior himself but he had spoken with those who had. “Those who have viewed only a skirt of these prairies speak of them with a degree of enthusiasm, as if it were only there that nature was to be found truly perfect.” Dunbar finally ended his passage this way: “They declare that the fertility and beauty of the vegetation, the extreme richness of the valleys, the coolness and excellent quality of the water found everywhere, the salubrity of the atmosphere, and above all, the grandeur of the enchanting landscape which this country presents inspires the soul with sensations not to be felt in any other region of the globe.”

There were “wonderful stories of wonderful productions,” Dunbar told Jefferson. Travelers spoke of mountains of pure or partial salt, and silver ore lying about in chunks on the prairie. But especially compelling were the stories of the wildlife riches of the great prairies. There were bears, “tygers,” wolves, and buffalo and other herds of grazers beyond imagination, even great herds of horses that had gone wild. There were stories of giant water serpents, although Dunbar did not credit those. But all the rest he believed to be real. It filled him with wonder, which he passed on to the American president.

Dunbar himself never got to see the region of those wonderful productions, but on one of the maps Jefferson was perusing—an untitled map assembled by American General James Wilkinson in 1804—the country Dunbar described was already labeled the “Great Plains.” But many Americans in the Jeffersonian Age did get to see and experience the wonder of these Great Plains. Among several such passages from Lewis and Clark’s ascent of the Missouri River into the western savannas, Meriwether Lewis wrote, on September 17, 1804, as the party was just entering the plains in today’s South Dakota, that “the shortness and virdue of the grass gave the plains the appearance throughout it’s whole extent of beatifull bowling-green in fine order.” None of the party could quite believe the wildlife spectacle before them: “a great number of wolves of the small kind, halks [hawks] and some pole-cats were to be seen. . . . this senery already rich pleasing and beatiful was still farther heightened by immence herds of Buffaloe, deer Elk and Antelopes which we saw in every direction feeding on the hills and plains.”

Lewis’s exploring contemporary, Zebulon Montgomery Pike, in 1806 found the High Plains of the Arkansas River country rather more barren than Lewis’s bucolic scene. He thought the Southern Plains a match for the “sandy desarts of Africa.” That same area of the plains inspired the Stephen Long exploring party of 1819–1820 to pronounce the central and southern stretches of the plains “unfit for agriculture” and a “barrier” to the continuing expansion of Americans westward. They did note, though, that “travelling over a dusty plain of sand and gravel, barren as the deserts of Arabia” was actually never tedious because of the thrilling wildlife spectacle, whose closest analogue once again was Africa. On the Arkansas, Captain John Bell wrote, they were endlessly in sight of “thousands of buffalo on both sides of the river.” Naturalist Thomas Say, the official discoverer of the coyote, added less romantically that the vast herds of animals they saw were never without a roiling, noisy, raucus accompaniment of “famine-pinched wolves and flights of obscene and ravenous birds.”

Americans and those who weren’t citizens of the continent were startled and curiously amazed by descriptions like this. The writer Washington Irving was enthralled enough to go himself and then write Travels in the Prairie. New York novelist James Fenimore Cooper wrote a Leatherstocking novel about the plains. The painter of Indians, George Catlin, was besotted and did his best, which often wasn’t so great, to capture prairie landscapes, as with his Big Bend on the Upper Missouri. Germans who trained with the legendary naturalist Alexander von Humboldt explored around the world, but one of the places they sought out was the American plains. Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied was one, who brought with him the amazing animal painter Karl Bodmer. It was Bodmer, with epic paintings like Landscape with Herd of Buffalo on the Upper Missouri, who went west with talents that could take the measure of the Great Plains. His collection of watercolors done on the Missouri in the early 1830s are some of our very best American Serengeti time-travel enablers. And there was John James Audubon. Of course. Audubon and his sons did almost the full suite of plains fauna, an ecological portrait gallery, from their 1843 trip up the Missouri. And in 1849 Francis Parkman told readers what it was like to “Jump Off” from the East into the great prairies in one of the celebrated books of the century, The Oregon Trail.

Even after the Civil War, when travelers, naturalists, and artists going west were responding to the Hudson River School’s focus on American mountains, the plains remained unforgettable for many, at least until the slaughterhouse of the market hunt commenced. The Russian nobleman, Grand Duke Alexis, went on his Great Plains safari in 1872, continuing a tradition of European elite hunter/adventurers on the Great Plains that went back to Sir William Drummond Stewart and Sir George Gore. American military officer Richard Irving Dodge wrote several books about the plains for an avid readership. So did George Armstrong Custer’s wife, Elizabeth. Teddy Roosevelt fled the East and family deaths to live on two ranches in the Dakotas, writing books like Ranch Life and Hunting Trails. Across the Atlantic, the plains—as ever—continued to intrigue the same set of eclectic adventurers who searched out the sources of the Nile or became white hunters in East Africa. The naturalist Ewen Cameron and his well-born photographer bride, Evelyn, went to the Montana badlands on their honeymoon in 1889 and never left.

Even in the twentieth century, after the previous three-decade slaughterhouse had rendered the plains eerily silent but before modern agriculture ripped the grass off much of the country, the region could still entrance. For the bohemian Mabel Dodge, journeying by train to New Mexico, the plains seemed a desert, but a beautiful one “that rolled away for miles and miles, empty, smooth, and uninterrupted. . . . I thought I had never seen a landscape reduced to such simple elements.” Young Georgia O’Keeffe, seemingly sentenced to a career as an art teacher in Outback Texas during World War I, out on the undulating sweeps near Canyon marveled at how you could just drive or walk “off into space.” To which she added: “It is absurd the way I love this country.” Writing her friend Daniel Catton Rich as late as 1949, O’Keeffe told him: “Crossing the Panhandle of Texas is always a very special event for me . . . driving in the early morning toward the dawn and rising sun—The plains are not like anything else and I always wonder why I go other places.”

Other twentieth-century women artists, like Mari Sandoz and Willa Cather, reacted similarly to the country that had produced them. As Cather told a back-home newspaper in 1921: “I go everywhere. I admire all kinds of country . . . But when I strike the open plains, something happens. I’m home. I breathe differently. That love of great spaces, of rolling open country like the sea—it’s the grand passion of my life. I tried for years to get over it. I’ve stopped trying. It’s incurable.”

Even without the great herds and their predators, with the landscape itself still largely intact the Great Plains struck many as terrestrial poetry. But people who got to see the “entire heaven and entire earth,” uncountable wildlife speckling the undulating sweeps, never forgot it. Not surprising, then, that America’s poet laureate of the nineteenth century, that ultimate American lover of being in the world, got captivated. Walt Whitman saw the plains for the first time after the Civil War, when the animals and native inhabitants still held sway and the frontier was then hosting one of the greatest dramas in the world. His reaction was simple and direct: “I am not so sure but that the prairies and plains, while less stunning at first sight, last longer, fill the esthetic sense fuller, precede all the rest, and make North America’s characteristic landscape.”

There’s an obvious question to pose here. What has happened to make the modern reaction to the Great Plains so different now? How, in other words, do you get from Walt Whitman and Willa Cather to “un-country”?

The answer self-evidently has to do with the extraordinary transformation the Great Plains underwent at our hands in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In effect we dismantled and demolished a 10,000-year-old ecology, very likely one of the most exciting natural spectacles in the world, in the space of a half-century. There were people who made careers out of that loss, among them the artists Charlie Russell and Frederic Remington and the writer Zane Grey, and what they mourned was what they saw as life in “the wilderness,” a thrilled-to-the-marrow life among native people and thronging wildlife and nature. As Grey believed, the West had offered the world one last chance to live in a state of nature as natural men and women. And then modern America had withdrawn the offer.

For women especially tuned in to the plains, like Cameron and O’Keeffe and Cather, it was not wildlife beyond imagining but a sense of freedom derived from a vast, uncluttered space of grasslands that appealed so strongly. “Space” and “like the ocean” served as code-words for the freedom available to independent women on the open grasslands of the plains in the early twentieth century. The novelist Mari Sandoz mourned the loss of the world of the Indians and in her books wrote longingly of the wild creatures that had blanketed her home state of Nebraska, but in the twentieth century she also thrilled to the effect of space O’Keeffe and Cather mentioned.

But historical forces that mounted in intensity as railroads and ranching and farming arrived destroyed much even of that Great Plains. The war on plains wildlife was the unkindest throat-slitting in the creation of “un-country,” but there was more. Act two was the agricultural assault. Because level, grassy plains did not appear to present the kind of obstacles to agriculture other landscapes did, with the animals removed, from the 1850s to the 1930s, homesteading policies privatized the overwhelming bulk of the American Great Plains. In western Kansas/eastern Colorado, the Big Breakout—that term referred to plowing the grasses under—took place under the nineteenth-century homestead laws and in the decades on either side of the twentieth century. In Oklahoma the land rushes resulting from Indian allotment was the trigger. Settlers broke out western Nebraska, the Dakotas, eastern Montana, and eastern New Mexico after Congress passed the Enlarged Homestead Act in 1909. In Texas, with its anomalous lands history and long devotion to privatization, the sale and breakup of the XIT Ranch in 1915, along with disposed railroad tracts, brought farmers by the trainload to the Llano Estacado and Rolling Plains there.

The losses to the foundations of plains ecology, the loss of the grasses themselves, are staggering to contemplate. Conservation biologists now hold up the tallgrass prairie, whose extent on the southern Blackland Prairie agriculture took down to less than 1 percent of its original coverage, as one of the unforgivable sins against nature in continental history. Losses in the areal extent of the grasslands in the mid-grass and shortgrass plains are also mind-boggling. By 2001 Saskatchewan had only 19 percent of its native prairie left. North Dakota possessed only 28 percent of its remaining prairie at the beginning of the century, and that was before the Bakken oil boom. Texas has an average of 20 percent of its prairie today, although the part of the High Plains I know best, the central Llano Estacado, is in far worse shape. Lubbock County, where I lived, by the 1980s had lost 97 percent of its native grasslands. Literally all that remained was in Yellow House Canyon, a grassy gorge too rugged to plow up and plant to cotton. It was the very spot I sought out to homestead.

The contrast between the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains in Lewis and Clark’s day was clear in the party’s longing to escape the wildlife-poor mountains and return to the plains. In our time, two centuries of history have accomplished an entire reversal: the federally managed Rockies are now home to most of the West’s wildlife, which fled there from the plains, while the privately owned Great Plains has become a monument to the American sacrifice of nature.

But this is a three-act story. Once we thrilled to the Great Plains. Then we wreaked havoc on its ecology and many came to despise the result. For the past three-quarters of a century, a third phase—undoubtedly not the last—has been building momentum. As a result of some bad historical misses, to an extent stage three is still a vision. But there have been some successes, too.

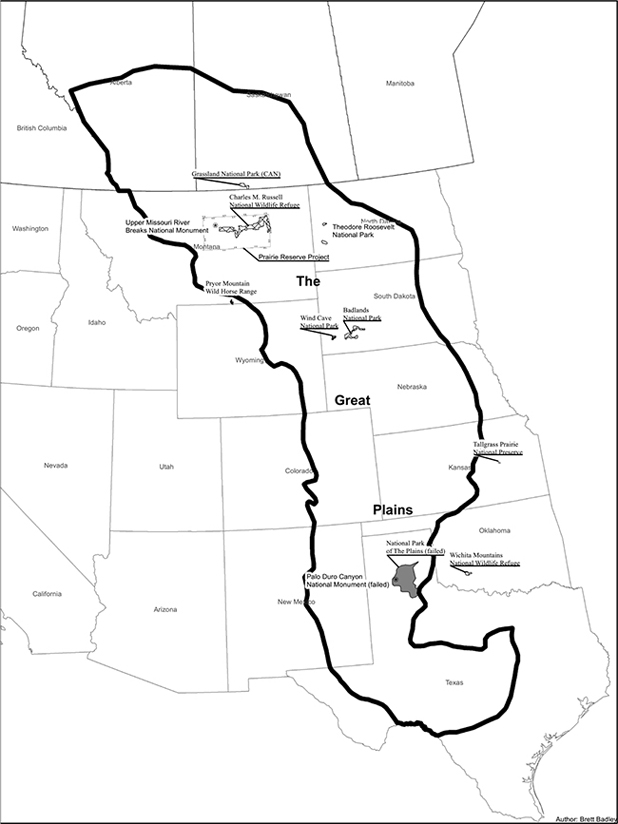

Re-wilding the Great Plains with its traditional charismatic big animals means finding landscapes where the antelope can play. In our time, environmentalism and conservation biology recognize natural grasslands and prairie ecosystems as some of the most under-preserved natural regions around the world. Despite an international push to set aside grand grassland parks to preserve the charismatic wild animals of the African plains—Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya, Kruger National Park in South Africa—conservation in the United States ironically overlooked or bypassed our own Great Plains in the federal preservation agenda. It’s beyond ironic that the first visionary call for an American national park, George Catlin’s in 1832, was for a park on the Great Plains, because the National Park Service has long been an embarrassment in its apathy towards plains parks. That began to change in the 1930s, but not before there were too many huge misses.

The major American conservation initiatives that gave us our national forest and national park public lands a century ago focused on western landscapes that were too high, too rocky, or too rough to farm. That meant mountain ranges and western canyons, places like the Rockies, Sierras, Cascades, and the Colorado Plateau became the bastions of the public lands. Except for a scattering of island mountain ranges on the Northern Plains, the powers that fashioned the western public lands almost entirely ignored the Great Plains, a country deemed grassy enough to ranch, with few impediments to farming, therefore ripe for homesteading. During the initial phase of national park history the scenic ideals of the Romantic Age also meant sublime scenery, by the standards of the age (and Old World tastes) almost always landscapes of great vertical relief.

Thus Yellowstone and Glacier and Rocky Mountain national parks, along with the great canyons like Yosemite, Zion, and the Grand Canyon, became the ne plus ultra examples of American parks, not merely monumental, but monumentally vertical. No landscapes on the plains seemed very interesting to a park service with this kind of value system. Although early on the NPS did accept three Great Plains parks—Sullys Hill in Nebraska, Platt in Oklahoma, and Wind Cave in South Dakota—the three totaled fewer than 30,000 acres altogether compared to 2.2 million acres for Yellowstone alone. Eventually the NPS downlisted all but South Dakota’s Wind Cave, which did acquire a herd of pure and free-roaming bison, although the park never grew beyond 33,000 acres. Other than Wind Cave, almost the only Great Plains nature preservation of the early twentieth century came when Teddy Roosevelt’s administration proclaimed a small mountain range in southwestern Oklahoma the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in 1905.

As the park service moved slowly away from what parks PR man Robert Sterling Yard called the “Scenic Supremacy of the United States” towards some incorporation of ecosystem values in its criteria for parks, a new problem for the plains surfaced. Until passage of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act in 1964, the park service had no acquisition budget, and that became an almost insurmountable obstacle in parts of the plains, where private ownership of the grasslands had reached the point where almost every potential site for a plains park that might house remnant plains animals confronted the obstacle of buying up private lands. In the 1920s the pioneer of community ecology, Victor Shelford, and a group called the Committee of Ecology of the Grasslands began to press for large Great Plains preserves based on ecological factors rather than scenic spectacles that would humble European visitors. They studied eleven sites, found four more than acceptable, and eventually submitted one (spanning three-quarters of a million acres in Nebraska and South Dakota) to the park service and Congress. But nothing came of it.

The philosophical direction the park service took in its early years was the result of the personal vision of its first director, a New Englander named Stephen Mather. Mather developed a set of evaluative criteria for new additions to the parks and national monuments system that his successor and protégé, Horace Albright, followed well into the 1930s. The prime directive in Mather’s criteria was a large, preferably contiguous area with natural features so extraordinary as to be of national interest. Mather wanted scenic parks, and he wanted them to be of a particularly unusual and impressive quality. So while scientists like Victor Shelford were thinking in terms of preserving representative ecosystems, the park service had the Mather scenery inertia to overcome. Consequently, as park service personnel began to look beyond the mountains and to heed the scientists’ interest in the Great Plains, they concentrated their efforts not on the rolling, grassy uplands most typical of the region, but on the more dramatic badlands and canyon lands country, the plains’ erosional equivalents of the Colorado Plateau. Plains history and the success of Yellowstone had them thinking about animals, too, but scenery was always first.

The problem was that no landscapes on the Great Plains measured up when compared to the scale of a Zion or a Grand Canyon. In the 1920s and 1930s the NPS disappointed the ecologists by turning down one proposal after another. But one area of the plains, the South Dakota Badlands, set the plains on the road eventually to a second plains national park.

Local advocates had proposed the yellow-and-cream South Dakota Badlands as a park as early as 1909, and since much of its acreage consisted of “excess” Indian lands and parcels passed over in the homesteading process, it was a prime candidate for a park service with no money. But as a badlands its sparse grass cover seemed too thin for wild herds in the Yellowstone model. And plenty of people in the park service held the proposed “Teton National Park’s” lack of vertical relief against it. At the time the broadly experienced Roger Toll was the chief investigator for new parks in the NPS. Toll visited the area in July of 1928 and within days decided that “it is not a supreme scenic feature of national importance.” The Badlands, he explained to his Washington superiors, “are surpassed in grandeur, beauty and interest by the Grand Canyon National Park and by Bryce National Park.”

Sixty percent of the Badlands had remained part of the public domain, though, and when the state of South Dakota agreed to acquire and transfer to the NPS 90 percent of the private holdings, Toll proposed a consolation. He recommended that the NPS use the Antiquities Act (whose targets were landscapes of unusual archaeological or geologic interest) to proclaim 68,000 acres of the area a national monument. Congress quickly approved Badlands National Monument in 1929. Eventually enlarged to some 250,000 acres, it became the Great Plains’ largest chunk of public lands with President Roosevelt’s proclamation opening it in 1939. Bison were gone, pronghorns very nearly so, and across the gray and saffron mounds and cliffs, hunters had already wiped out the famous local population of Rocky Mountain bighorns decades before. All three species could be (and were) recovered, but the Badlands’ often sparse grass cover and relatively small size kept it from becoming a plains version of Yellowstone’s wealth in wildlife.

Something similar happened with North Dakota’s Little Missouri Badlands, which the NPS initially found “too barren” for a national park. At first local ranchers opposed the idea of a park vehemently. But rancher opposition swirled away with the Dust Bowl and the Depression, and the NPS finally acquired the area in 1947—but as a historical/memorial park based on President Theodore Roosevelt’s presence in the area. With its pronghorns and bison herd and, eventually, wild horses, North Dakota’s Theodore Roosevelt National Park came closer to the Great Plains ecosystem park Shelford and the ecologists were calling for. But the park’s two units were small, barely 70,000 acres total, and coyotes excepted, the NPS allowed none of the big predators like the grizzlies (and eventually wolves) that roamed Yellowstone.

The public lands reserve on the Northern Plains that would eventually have the most promise as a Catlin-like wild possibility began life modestly in 1936 as the Fort Peck Game Range, initially managed by the Bureau of Biological Survey. The bureau had sent its well-respected ecologist, Olaus Murie, to report on the area surrounding the reservoir that the Corps of Engineers was creating on the Missouri River, expecting Murie to suggest a waterfowl refuge. Murie’s conclusion was that the broken, badlands-studded valley held much greater promise as a preserve for big wild animals. From small things, large results. By the 1970s the Game Range had become the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, and soon enough it was the second-largest one in the Lower Forty-Eight. For re-wilding the Great Plains, its steady accretion in size made it a real possibility, and grassland conservationists began paying very close attention.

And the Southern Plains? During the 1930s, when scientists were trying to pull the NPS in the direction of ecosystem thinking, actually it was on the Southern Plains where—at least for a few years—park personnel finally began to toy with the idea of a large ecosystem Great Plains park, one that would have gone far towards recapturing the plains’ wildlife spectacle and ancient poetry with an Africa-style park. With an omnibus parks bill in 1978, the NPS would eventually upgrade both Badlands and Theodore Roosevelt to full national park status, and along with Wind Cave and Saskatchewan’s Grassland National Park, established in 1981, these gave the Northern Plains a fair start in the direction of eventual re-wilding. The Southern Plains, on the other hand, would end up entirely lacking a national park of any size. The plains below the Arkansas River does possess a scattering of national wildlife refuges and very small national monuments, notably Alibates Flint Quarry in the Texas Panhandle and Capulin Volcano on the New Mexico plains. But in the twenty-first century, the Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico plains remain “un-country.” How that happened is quite a story.

It is also historically odd. With the exception of the Black Hills, Palo Duro Canyon—the great canyon the Red River carved through the Llano Estacado plateau in West Texas—was probably the most famous landscape on the Great Plains. A Comanche hideaway and home to Charles Goodnight’s ranch, Palo Duro was both a scenic and vertical jewel inset into vast grasslands. It seemed a perfect locale for the large Great Plains park ecologists were hoping for. The Texas congressional delegation began bringing Palo Duro up as a potential park as early as 1908. But the big canyon had long since gone under private fence, and the truth was that only a handful of people had ever seen it, at least until a young Georgia O’Keeffe exhibited paintings of it in New York in 1917. Once when it was opened to the public, 14,000 people showed up to see it on one day.

A 60-mile long, 800-foot deep roar of color, Palo Duro not only had historic and scenic values, it also exposed 250 million years of North American geology going back to the Permian Age. Goodnight and his wife, Mary, had preserved a small herd of distinctive Southern Plains buffalo on their ranch in the canyon, and above the canyon rim there were intact grasslands where thousands of pronghorns and wild horses had once roamed, and could again. Texas was already planning a small state park there in the early 1930s, and Palo Duro had some local champions, among them writer and historian J. Evetts Haley, who was writing a biography of Goodnight. Even Enos Mills, “the John Muir of the Rockies,” journeyed to West Texas to support a national park in Palo Duro. But it seems to have been Horace Albright’s chance layover in Amarillo in 1932, leading to a perusal of photographs of Palo Duro, that led the director to decide to add the big plains canyon to an upcoming investigative tour of possible Texas park sites by Roger Toll.

Until his untimely death in a car crash later that decade, Toll was a one-man-make-it-or-break-it whirlwind for the NPS, the man whose opinion basically gave the West most of the national parks it got in the 1930s and 1940s. At the time of his Texas tour in the winter of 1933–1934, Toll was still very much a Mather-style scenery advocate. But at park service offices in Washington the ecologists evidently regarded his upcoming examination of Palo Duro Canyon as the master-stroke of plains preservation they hoped for. While Toll journeyed to Texas, the scientists were assembling maps and materials for the creation of a million-acre “National Park of the Plains” around Palo Duro, a huge swath of territory half the size of Yellowstone that would have included the canyons but also adjacent grasslands all around the canyon rims with the idea of restoring key wildlife like bison and pronghorns.

In company with Haley, Toll spent four days in Palo Duro in January 1934, traversing much of its sixty-mile length from a series of waterfalls at the upper end down to the stunning Narrows gorge of a dramatic side-canyon called Tule, which explorer Randolph Marcy had described in 1852 as the most dramatic scene he’d ever witnessed. Toll was impressed: he regarded Palo Duro as scenically superior to the Badlands he had recommended for monument status six years earlier. But whereas the Grand Canyon was monumental, like the Dakota Badlands, Palo Duro nudged Toll’s scenic meter only up to “interesting and picturesque.” In sum, as Toll wrote in his report, the NPS’s scale of sublimity made Palo Duro “not well qualified for a national park as its scenery is not of outstanding national importance.” He told the new NPS director, Arno Cammerer, that unfortunately, “It would rate below the present scenic national parks.” Toll was also concerned about real estate values in Texas, where land wasn’t quite as inexpensive as it had been in the Dakotas.

Even as Toll was damning Palo Duro with faint praise, ecosystem values continued to gain ground in the NPS. And the West Texas canyon had now caught the eye of the NPS. The service’s new Everglades National Park in Florida, established for its ecological values instead of classic scenery reasons, demonstrated that NPS interest in ecosystems was now serious. And new parks like Acadia (Maine), Shenandoah (Virginia), and Great Smoky Mountains (Tennessee/North Carolina) demonstrated that it wasn’t impossible to create national parks in regions lacking a public domain.

A Texas Democratic Senator named Morris Sheppard now stepped up to champion a Great Plains preserve in West Texas, more to aid the collapsing farm economy of the 1930s, you suspect, than because he was an advocate of re-wilding the Southern Plains. As High Plains farming fell apart in the Dust Bowl and the federal government took back thousands of acres of former homesteads, Sheppard began to press for a different form of federal economic salvation for the Dust Bowl region by having President Roosevelt make Palo Duro into a national monument by proclamation.

Noted geologist Herman Bumpas, an advisor to the NPS, became an inside supporter of this idea. As Bumpas told park officials in Washington, a Palo Duro Canyon National Monument seemed almost a necessity in another of the service’s new themes: public education about the natural world. Located just south of Route 66, the famed principal automobile route across the country in an age when Americans were taking to the road in record numbers, Palo Duro could play the geological role of the “First Chapter of Genesis” for tourists heading west on the Mother Road, Bumpas said, since its bottom-most geological strata ended exactly where those at the rim of the Grand Canyon began.

So in October 1938, the park service initiated a second review of Palo Duro Canyon. This time the idea was far more modest than the earlier vision of a Great Plains park half the size of Yellowstone. The planned Southern Plains national monument of 134,658 acres would be twice the size of the Theodore Roosevelt unit, although not quite up to Badlands size. By this point in the evolution of the park service, the evaluation strategy was much more systematic than when Roger Toll’s visual comparison of a landscape with Glacier or the Grand Canyon could decide its fate. From the Santa Fe regional offices, eight NPS experts in as many fields descended on Palo Duro during March and April 1939.

The end result was an eighty-nine-page document assessing everything from the botany and wildlife of the canyon to its geological and historical significance. The national monument report naturally included a detailed estimate of the acquisition cost, too, a figure that ran to $294,000, plus $264,000 to fold in the 15,000-acre state park. The boundaries were to extend from the waterfalls section 35 miles down the canyon to a place called Paradise Valley, owned by Charles Goodnight’s old ranch, the JA. The boundaries excluded Tule Canyon and its spectacular gorge, but future monument expansion no doubt would have taken in that section. As an indication that the park service had not yet fully embraced the idea of ecological restoration on the plains, the 1939 report did not include any significant description of bison or pronghorn restoration, let alone wild horse recovery. By that year the grand idea of a large, restored Southern Plains Yellowstone seems to have evaporated.

Of the scientists, it was the geologists who were most excited. Geologist Charles Gould made an eloquent plea in his section of the report. “From the standpoint of Geology and scenery,” he wrote, “Palo Duro is well worthy of being made into a national monument. It is the most spectacular canyon, carved by erosion, anywhere on the Great Plains of North America.”

In Washington the Santa Fe field team’s recommendation in favor of monument status met with mixed reviews. Those who had actually seen Palo Duro were uniformly in favor of national monument status. But again, in a region of the West that almost entirely lacked public lands, the most important element was cost. What the NPS required in the 1930s was a state government or a group of wealthy patrons to step up and write the check for a new park or monument. When word got out, public support did come in, but it was mostly from places like Denver, Albuquerque, and Oklahoma City. The Texans in whose state the new national monument would reside, however, seemed oddly ambivalent. And ambivalence was the swan song for Palo Duro National Monument. When Senator Sheppard inquired about the status of the monument in 1940, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes told him that Interior stood “willing to recommend the establishment as a national monument of approximately 135,000 acres of land” once donors stepped forward to acquire the property. In Maine, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, wealthy donors and public campaigns were raising money in that same decade to acquire new park lands. But in Texas? No wealthy oil visionary from the Lone Star state stepped forward the way the Rockefellers were then doing in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, to create Grand Teton National Park.

So ambivalence, or apathy, or perhaps just ideological opposition to public lands killed a large national monument in West Texas that could eventually have served as a core for re-wilding parts of the Southern Great Plains. Losing an expansive Southern Plains national monument—to say nothing of that earlier, Catlin-like vision of a million-acre Great Plains Yellowstone around Palo Duro—were the biggest missed opportunities on the plains in the twentieth century. Texas’s park division has managed since to double the size of the state park to about 30,000 acres and has created another 16,000-acre park 35 miles south along the Caprock escarpment that now has a free-roaming bison herd rounded up on the JA Ranch. Those just aren’t much consolation for those who know Palo Duro’s larger story.

With the release of the new Mexican gray wolf recovery plan in 2015, wolves sooner or later are going to be on the Southern Plains again. Wild Earth Journal has even published a re-wilding proposal for a biological corridor encircling the Caprock escarpment of the Llano Estacado where wolves and lions might thrive. But it takes public lands for a vision like that to work. In 2006 and 2007 the Nature Conservancy released highly detailed, fine-grained biodiversity/conservation studies of both the Southern Plains and Central Plains ecoregions. They were optimistic that on the Central Plains, primarily in New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and Nebraska, 50 percent of 56 million acres of areal grasslands remain intact and unplowed. But 92 percent of the entire area is in private hands, only 3 percent in federal ownership, and remaining grasslands are patchy across all of it. On the Southern Plains, primarily Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico, conditions are even worse, with less intact grasslands and a mere 3.6 percent of the landscape in public (federal plus state) ownership.

Many small-scale conservation opportunities exist on the Central Plains and Southern Plains, but the burden of plains history rests heavy here, with little hope for re-wilding on a scale that would inspire national and international excitement. In the nineteenth century this country was sometimes called the “Zahara of North America,” a wilderness its explorers said “seems particularly adapted as a range for buffaloes, wild goats, and other game.” Whether anything like the opportunities of the 1930s ever stands so willing and fetching before us again appears dubious now.

In the 1950s and 1960s residents of the Great Plains and even those outside the region took for granted that we had resolved the disaster of the Dust Bowl with improved farming practices and (naturally) “technological fixes.” Of course we had also managed by the 1940s to tap into the Ogallala Aquifer, with such an apparent abundance of clear, pure water surging through the well casings that the country from Texas to Nebraska launched into an era of unprecedented growth, symbolized by factory farming that often went on even during the night. Everyone from those happy generations assumed that like the rest of the West and the country, the arc of history for the region was onward and upward towards unlimited growth and population. Then, in the 1970s, the aquifer began to drop, rapidly and to depths that made pumping the water up no longer so cost-effective. Dust returned, too, and in the 1980s came census reports showing steady out-migration and falling revenues all across the plains. At that point something like a new consciousness emerged about the Great Plains, and serious reappraisal of the burden of modern plains history began.

The Colorado geographer William Riebsame has tried out evolutionary models to assess how American society actually did respond to the Dust Bowl. Riebsame contrasted true adaptations with mere “resiliency,” or a tendency to rebound to its previous strategies of inhabiting a place following a major disturbance. In short, Riebsame tends to think that many of the changes Great Plains society made to combat the Dust Bowl, and now the drawdown of the Oglalla Aquifer, have tended to be resilient rather than adaptive. Contour farming, listing, and center-pivot irrigation were all merely technological refinements of what we had been doing when the crises struck. The ideas and machines that seemed to “fix” the Dust Bowl, in his view, in reality were adjustments to the market, not to nature in a semi-arid, windswept setting that’s subject to periodic drought and has never done anything quite so well as grow grass and support wild grazers and predators.

What makes the future of the Great Plains scary is, of course, predicted global climate change, and at rates far faster than anything humans have ever experienced. Climate science has repeatedly singled out the Southern and Central Plains, especially, as among America’s regions that will be hardest hit by global change. Some scientists have asked us to imagine not just a repeat of the Dust Bowl, which was only a decade-long phenomenon, but mega-droughts that could change the plains so drastically as to feature a significant and rapid advance of Chihuahuan Desert conditions northward. So it seems self-evident to many that the Great Plains is on the cliff edge of a major paradigm shift, and it could be one that might make the world of the past more appealing than it has ever been. The plains artist Charlie Russell spent his whole career, even into the 1920s, trying to re-create what he thought of as a dreamtime world on the plains. He had seen the plains when “the land belonged to God” briefly, in the 1880s, and mourned the loss of it his entire life. Something like what he dreamed, we may get to live.

By the twenty-first century the American Serengeti shows only a small scattering of successfully preserved national landscapes, along with some regrettable failures in a region of the West that nearly got bypassed by the national parks movement. Only Montana's American Prairie Reserve holds the potential of a future Yellowstone of the Great Plains.

A new vision for the Great Plains is out there. As Frank and Deborah Popper have come to argue with respect to their Buffalo Commons idea, plains out-migration, the emergence of Indian peoples as major environmental players, endangered species recovery of wolves on the western borders of the plains, and a new excitement about ecological restoration generally are making their Buffalo Commons idea a reality, just on a smaller and more decentralized scale than they had originally envisioned.

This is no doubt a correct assessment as far as it goes. There is a great deal of private, grass-roots, and even state-based re-wilding going on across the plains. There are groups like the Southern Plains Land Trust in southeastern Colorado, which is seeking to acquire High Plains acreage for restoration. The Nature Conservancy now has an office in Amarillo to assist Texas Parks and Wildlife’s long-running efforts to enlarge its Llano Estacado parks and maybe create a large, High Plains state park where buffalo, pronghorns, elk, and hopefully wild horses can roam at large again. The Great Plains Restoration Council in Denver is working as an information clearing-house for hopes to create a million-acre Buffalo Commons somewhere on the plains. Nonprofits like the American Buffalo Foundation and the High Plains Ecosystem Restoration Council are attempting to advance that cause, too. There are similar groups in the Black Hills, pushing for a “Greater Black Hills Wildlife Protection Area,” and in Nebraska (where the focus is on the Sand Hills), in Kansas and Oklahoma (focused on the Flint Hills and tallgrass prairie), and in North Dakota, where the battle against the consequences of fracking and energy development rage on.

Because on the Northern Plains there is more public land in the form of parks, national grasslands, and Bureau of Land Management parcels, and because Indians there managed to retain tribal reservation holdings in a way that didn’t happen on the Southern Plains, the best hope for a grand George Catlin plains wildlands now lies in the north, and specifically in the state of Montana. Even the Sierra Club, for decades interested only in mountains, has become a prairie advocate for this area. It has had its own evolving proposal for High Plains biological corridors linking preserved “core” areas, modeled on the Yellowstone-to-Yukon idea for the Northern Rockies, but has now bought in on the exciting re-wilding project that is unfolding in Montana.

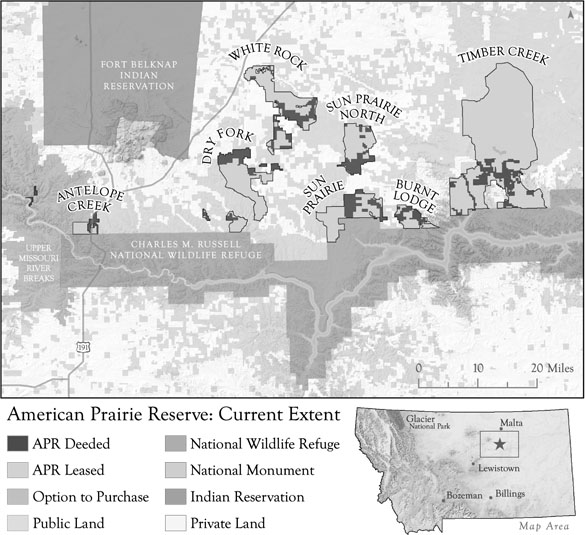

The most exciting prospect for re-wilding the Great Plains with its nineteenth-century charismatic fauna is the American Prairie Reserve, which seeks to merge already protected federal lands with incisive private acquisitions to create a twenty-first-century wildlands on the Northern Plains even larger than Yellowstone Park.

Conservation biologists say that to work in re-wilding terms, a Catlinesque plains park should at least cover 2.5 million acres, about the size of Yellowstone (although some of them insist that 10–20 million acres would be a more effective size). Getting some re-creation of the historic Great Plains on this scale would be an act of conservation statecraft on the level of creating the first national parks in world history, or passing a Wilderness Act that has protected so much American nature. Restoring historic Great Plains nature would be a cultural goal for the United States that its citizens, and no doubt the citizens of the world, would celebrate for centuries.

There is nothing quite so grand as a 10-million acre Great Plains park under way in the real-life world, but there is something close to this vision. It acquired life from President Clinton’s 2001 proclamation of an Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument extending downstream from the White Cliffs section of the Wild and Scenic Missouri River. The new monument drapes along 150 miles of the river—the river of Lewis and Clark, Catlin, Maximilian and Bodmer, Audubon, and Teddy Roosevelt—that was so important to plains history. If we can merge this 377,346-acre National Monument with the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge farther downriver, now grown to a whopping 915,814 acres, then federal managers would have the makings of a Yellowstone-sized chunk of the plains located in a state that already has wolves and grizzlies in its mountains and buffalo and Spanish mustangs readily available nearby. Of course there are obstacles, plenty of them. The national monument is managed by the BLM and the wildlife refuge by the Fish and Wildlife Service, for one thing. Far more importantly, both are highly checkerboarded with private lands and ranchsteads and livestock grazing throughout.

During the lead-in to President Clinton’s announcement of the new national monument, the Nature Conservancy released the first of its Great Plains studies, Ecoregional Planning in the Northern Great Plains Steppe, examining the prairie sections of five states, plus two Canadian provinces. That study argued that with 60 percent its grasslands intact, with that percentage going as high as 95 percent in the western parts of the study area, and with significant public lands already in place, in the twenty-first century the Northern Plains—“where landscapes spanning across millions of acres represent perhaps the most intact grasslands in North America”—was unquestionably the best re-wilding candidate on the American Great Plains. Private in-holdings scattered through the public lands, however, were going to be a major issue. An international assessment by ecologists of grasslands around the world a few years later also singled out eastern Montana as one of only four global candidates for plains conservation on a large scale. By that time another international environmental group, the World Wide Fund for Nature, had begun an effort to identify critical acquisition properties in the area with a solution in mind for merging the public parcels.

In the White Cliffs on the Wild and Scenic Missouri River. Dan Flores photo.

American Prairie Reserve, a nonprofit set up to turn this grand, Yellowstone-like vision into reality, opened offices in Montana in 2001 to see if the Rockefeller family’s strategy of buying up private lands to create Grand Tetons Park might work in the twenty-first century. The organization has raised more than $80 million (there are big-time donors from both coasts as well as thousands of small donors) and it has an epic plan: to acquire a critical half-million private acres in order to stitch together the existing public lands along the Missouri into a restored Great Plains preserve that could approach 3.5 million acres in size, almost half again larger than Yellowstone Park, for stocking a bison herd, at a minimum, of 10,000 animals. As with most visionary endeavors, misinformation abounds, including articles in the conservative press carrying inflammatory titles like “Bison-Loving Billionaires Rile Ranchers with Land Grab.” But many major players, including the National Geographic Society, which produced a 2010 film about the idea—American Serengeti—are all in.

Because re-creating the American Serengeti does mean acquiring private lands from ranchers who often are rabidly against the idea of reversing the flow of history and despise any thought of reintroducing bison to the plains, what American Prairie Reserve has been cautious about publicly proclaiming is that it would love to see grizzlies and wolves colonize the Reserve from their strongholds in the western mountains. But ultimately what its board and supporters truly want restored is the whole suite of animals on the historic plains, using Yellowstone as a template for the world-class Great Plains park we never got. The Reserve’s Hilary Parker told me flat out: “Make no mistake: Our goal is nothing short of re-establishing all of the megafauna of the original plains.” Its supporters, the Bozeman-based Ecology Center and the Predator Conservation Alliance, have a High Plains Ecosystem Recovery Plan that envisions re-creating all the ecological processes of the Northern High Plains—classic re-wilding, in other words, with wild bison ranging free in large numbers and grizzlies and wolves and fire all returned to the region. And perhaps, with some nudging and a new appreciation for the long evolution of horses on the continent, even the wild horses that helped give the historic plains some of the magic and poetry of the American Pleistocene.

Admittedly this is a romantic vision. It will without question be difficult to make happen in the twenty-first-century political climate. What it does hold out is a promise of sustainability resting on what this plains world wants to be, on its ancient ecological base. Because, simply enough, what has always worked best on the Great Plains was what was there all along.

A pair of ecologists, Fred Samson and Fritz Knopf, have been arguing for two decades that for preserving biological diversity in North America, the Great Plains has become “perhaps the highest priority” in conservation. The first time I read their argument about prairie conservation I knew a statement like that was going to strike some readers, utterly bored by the plains in their present, skinned form—and almost surely never having read Lewis and Clark, Audubon, Cather, or O’Keeffe—as ridiculous, some kind of bad joke perpetrated by science nerds who don’t quite get that it’s not funny.

Not long after, though, three friends and I had the chance to load our gear into canoes and head off for a float trip adventure on the Wild and Scenic stretch of the Upper Missouri River. After two days of leisurely paddling down the river we were lucky enough the second afternoon to be the only ones to set up camp in the stunning White Cliffs Narrows of the Missouri. The feeling from the morning that followed has never left me.

Sunrise that next morning came on like something out of a Karl Bodmer painting. I had awakened maybe an hour before dawn, looked around at the setting while barely conscious, then had let the murmuring river carry me away . . . only to be yanked, wide-awake, out of my sleeping bag a few moments later as slanting yellow sunlight caught the cliffs across the river with the blinding, reflective glare of a searchlight. It was like someone had turned on a 300-watt light in a darkened room, and it had me out of my bag and standing at water’s edge with my mouth open in what I realized, after a moment, was a form of shocked recognition of something that retreated just around the corners of my mind.

I had never been on the Missouri River before. But standing there under that impossibly lit sky, watching ducks arrowing low over the surface of the water and a small herd of mule deer pogoing away through hoodoos and pedestal rocks at my sudden appearance, while a coyote yipped a dawn serenade across the river, after a few moments it came to me. I had read books and pored over nineteenth-century art and dreamed daydreams of the wilderness Great Plains for much of my life, and now here I stood, on the banks of the Missouri, in the very stretch where Meriwether Lewis had wondered whether these scenes of “visionary inchantment would never have and end.” Just downstream from where I stood I knew that two centuries earlier, William Clark, wandering amongst a hundred dead bison washed against the shore, had found wolves in such great numbers and so “verry jentle” that on some unfathomable impulse he killed one with a stab of his bayonet. Karl Bodmer had painted the very cliffs I now watched. He, too, had seen this brittle sunrise light begin to soften to peachier, moisture-filled hues.

This place was déjà-vu for me not from some past life, but from the minds of others, who had made me know what a magical world the Great Plains once had been. The poetry of the plains was considerably fainter in my time on earth, but this particular morning on the Missouri I was hearing enough of the passages to realize that despite all, we had not entirely lost the American Serengeti. Not yet.