Having worms eat your food waste can lead to healthier plants. This happens when you use the vermicompost from your worm bin on your houseplants and gardens. What is the nature of this rich humus, and how should you use it?

Remember the distinction between worm castings and vermicompost. Worm castings are deposits that once moved through the digestive tract of a worm. Vermicompost is a dark mixture of worm castings, organic material, and bedding in varying stages of decomposition, plus the living earthworms, cocoons, and other organisms present.

If you choose a low-maintenance system, a large proportion of your vermicompost will be worm castings. A worm casting (also known as worm cast or vermicast) is a biologically active mass containing thousands of bacteria, enzymes, and remnants of plant materials and animal manures that were not digested by the earthworm. The composting process continues after a worm casting has been deposited. In fact, the bacterial population of a cast is much greater than the bacterial population of either ingested soil or the earthworm’s gut.

An important component of vermicompost is humus. Humus is a complex material formed during the breakdown of organic matter. One of its components, humic acid, provides many binding sites for plant nutrients, such as calcium, iron, potassium, sulfur, and phosphorus. These nutrients are stored in the humic acid molecule in a form readily available to plants and are released when the plants require them. Humus increases the aggregation of soil particles, which in turn enhances permeability of the soil to water and air. It also buffers the soil, reducing the detrimental effects of excessively acid or alkaline soils. Additionally, humus has been shown to stimulate plant growth and to exert a beneficial control on plant pathogens, harmful fungi, plant parasitic nematodes, and harmful bacteria. One of the basic tenets of gardening organically is to carry out procedures that increase the humus component of the soil; earthworm activity certainly does this.

You will have several buckets full of vermicompost from your worm bin. Use it selectively and sparingly. Vermicompost is loaded with humus, worm castings, and decomposing matter. The cocoons and worms present are unlikely to survive long outside the comfort of your bin. Plant nutrients will be present, both in stored and immediately available forms. Vermicompost in sufficient quantities also helps to hold moisture in the soil, which is an added advantage during dry periods.

Vermicompost will not “burn” your plants as some commercial fertilizers do, but since your supply will be limited, use it only where it will do the most good. One method is to prepare your seed row with a hoe, making a shallow, narrow trench. Sprinkle vermicompost into the seed row. In this way, the new seeds will have the vermicompost as a rich source of nutrients soon after they germinate and during early stages of their growth.

For transplanting such favorites as cabbage, broccoli, and tomatoes, which are usually set out in the garden as young plants, throw a handful of vermicompost in the bottom of each planting hole you dig. Don’t worry if worms or cocoons are present in the vermicompost. While the worms are alive, they will produce castings and add nitrogen from their mucus, but they are not likely to do all the other good things that worms do for the soil. Also, don’t expect your redworms to thrive in your garden. They are not normally a soil-dwelling worm, and they require large amounts of organic material to live. If you were to add large quantities of manure, leaves, or other organic material, you might find that a few Eisenia fetida survive, but most will probably die. When they do, their bodies will add needed nitrogen to the soil, so all is not lost! Hopefully, your gardening techniques will improve the organic matter concentrations in your garden so that the soil-dwelling species of earthworms will be fruitful and multiply.

You will use most of your winter production of vermicompost during spring planting. Any remaining material can be applied later in the season as a topdressing or side-dressing. At this time, you won’t want to disturb the growing plants’ root systems, but it is a simple matter to sprinkle vermicompost around the base and dripline of your plants, giving them an additional supply of nutrients, providing organic matter, and enabling the midseason plants to benefit from vermicompost’s water-holding capacity.

After several months of low-maintenance technique, the contents of the worm bin will be a dark, crumbly material that smells like earth. Since little food is left in this material for earthworms, very few worms will be present. Populations of active microorganisms will also have dwindled; those remaining will be in a dormant state awaiting reactivation in a suitable environment of new food and moisture.

Except for some large chunks, most of this worm-bin material is worm castings. Worm castings differ from vermicompost in being more homogeneous, with few pieces of recognizable bedding or food waste. When dried and screened, castings look so much like plain, black organic topsoil that you may be surprised to recall that little or no soil went into the original bedding.

While some drying of worm castings is desirable, it is best not to let them dry to the point that they become powdery, for it then becomes difficult to wet them down. A crust may form on the surface, causing slow water penetration. Worm castings with about 25 to 35 percent moisture have a good, crumbly texture and earthy smell, and are just about right to use on your plants.

Although pure worm castings provide many nutrients for plants in a form the plants can use as needed, some precautions should be taken in applying the castings. The organic material present in food waste likely will have broken down to a greater extent in worm castings than in vermicompost. More carbon will have been oxidized and given off as carbon dioxide, leaving nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and other elements to combine to form various salts.

Worm castings may not serve as a “complete” fertilizer for some plants. For one thing, high concentrations of some salts can inhibit plant growth. Additionally, worm castings often have a pH of 8 or higher and thus may not be suitable for acid-loving plants. The solution is to mix worm castings with other potting materials. In this way, plants gain the advantage of the nutrients present without suffering from excessive salt concentrations or changes in pH (see Maintaining Acidity for information on pH).

An intriguing experiment that seemed to verify the need to dilute pure castings was conducted by a horticulturist at the Kalamazoo Nature Center in the 1970s. Three sets of African violet plants were potted, each set in a different medium. Some grew in 100 percent potting soil; some in 100 percent worm castings; and some in equal amounts of worm castings, perlite, and Michigan peat. When the plants grown in potting soil were compared with those grown in worm castings, the castings-grown plants were generally healthier. Those grown in the potting soil showed chlorosis (yellowing) of some leaves, a sign of possible nutrient deficiency.

The plants grown with worm castings diluted with perlite and peat were distinctly more vigorous than the other two sets of plants. Leaves were larger, greener, and more robust. A likely interpretation of this experiment is that although the pure castings provided more nutrients for the young plants than the potting soil, salt concentrations in the castings may have been great enough to inhibit their growth. The plants in the third set had the benefit of nutrients from the castings but were not inhibited by too high a concentration of salts, since the concentration had been reduced by dilution with the perlite and peat.

In the 1980s, Dr. Clive Edwards, now of Ohio State University, led a team of scientists who conducted extensive plant growth studies that compared worm castings to commercial potting media in his native England. Castings were produced by worms working on a variety of wastes, such as cattle and pig manures, brewery waste, and potato waste. Although adding magnesium and adjusting pH to decrease alkalinity were sometimes necessary, media containing worm castings produced plants with as good or better seed germination and plant growth, and earlier flowering. This was true even when worm castings comprised as little as 5 percent of the mixture. Other more recent work supports these findings. It should be noted that reviews of this study use the terms worm castings and vermicompost interchangeably.

A 2007 study by Edwards and Dr. Norman Arancon confirmed that vermicompost can increase germination, growth, and yields of crops. Flowers, vegetables, and fruits were grown in greenhouses and fields. The researchers found that growth rates and yields improved more with lower applications than with higher ones. A 100 percent vermicompost application yielded less than a 20 to 40 percent vermicompost mixture. Again, it is possible that this was in part due to higher amounts of inorganic salts in the compost. This study also showed that large amounts of plant growth hormones exist in vermicompost. The researchers concluded that a wide range of plant pests were suppressed in vermicompost and that plant pathogens were reduced, as were plant parasitic nematodes.

Investigations are continually under way to refine this knowledge further. As scientific and commercial development of vermicomposting proceeds, the true economic value of worm castings will become apparent. In the meantime, your plants certainly will benefit from the castings the worms in your worm bin produce.

Some people suggest “sterilizing” potting mixes and worm castings prior to use with houseplants and in greenhouses in order to kill organisms that could cause plants trouble in a confined environment. The term “sterilizing” is being used loosely here, since the dictionary definition of sterilization is “the destruction of all living microorganisms, as pathogenic or saprophytic bacteria, vegetative forms, and spores.” Surgical instruments, for example, are sterilized in an autoclave under high temperature and pressure for a specified period of time. For our purposes, it would be more correct to say that potting soil is pasteurized; that is, it is exposed to a high temperature or poisonous gas for a long enough period of time to kill certain microorganisms, but not all. In any case, whether you prefer to call it sterilize or pasteurize, I don’t recommend that you do either to worm castings. Soil (vermicompost) is a dynamic, living entity, and much of its value comes from the millions of microorganisms present.

One concern many people voice about using worm castings directly on their houseplants is “Won’t those little white worms and all those bugs I can see crawling around hurt my plants?” Probably not. The enchytraeids eat dead and decaying material, not living plants, and so do the mites and springtails that are likely to still be present when your vermicompost is almost all worm castings. The organisms that thrived in your worm box are not likely to be the kind that also attack living plants. If there are just a few, don’t worry about them.

There may be a lot. If you have a true aversion to having visible critters in the worm castings you want to sprinkle under your plants, place your worm castings on a sheet of plastic outdoors in the sun. Put another sheet of plastic on top, and let this “solar heater” warm things up a bit. Most of the white worms will move onto the plastic, and most of the mites and springtails will be killed from the heat. Collect your castings in a few hours. They will be ready to use in potting mixes, as topdressing, or in your garden.

Have you ever tried to germinate an avocado pit? Have you tried the trick with the three toothpicks, inserting them around the diameter of the pit, placing it on top of a jar of water, and keeping it watered for . . . well, months? Until you either got tired of it or it finally did sprout?

Well, have I got a deal for you! Throw your pits into your worm bin, cover, and forget about them. That’s all. In time — it may take months, but be patient — you will find a taproot coming out of the bottom and a sprout coming out of the top. When this happens, transfer it to a pot. One winter, nine out of ten avocado pits I tried this way germinated. I now have more avocado plants than I know what to do with — in the living room, on the front porch, on the side porch, in my office. . . You, too, can be the first on your block to be a success with your sprouted avocado pits.

Worm castings may be mixed with various concentrations of potting materials, such as coir, sand, topsoil, perlite, vermiculite, or leaf mold. One satisfactory mix of equal parts by volume has these ingredients:

Experiment with different mixes, and find the ones that suit your favorite plants.

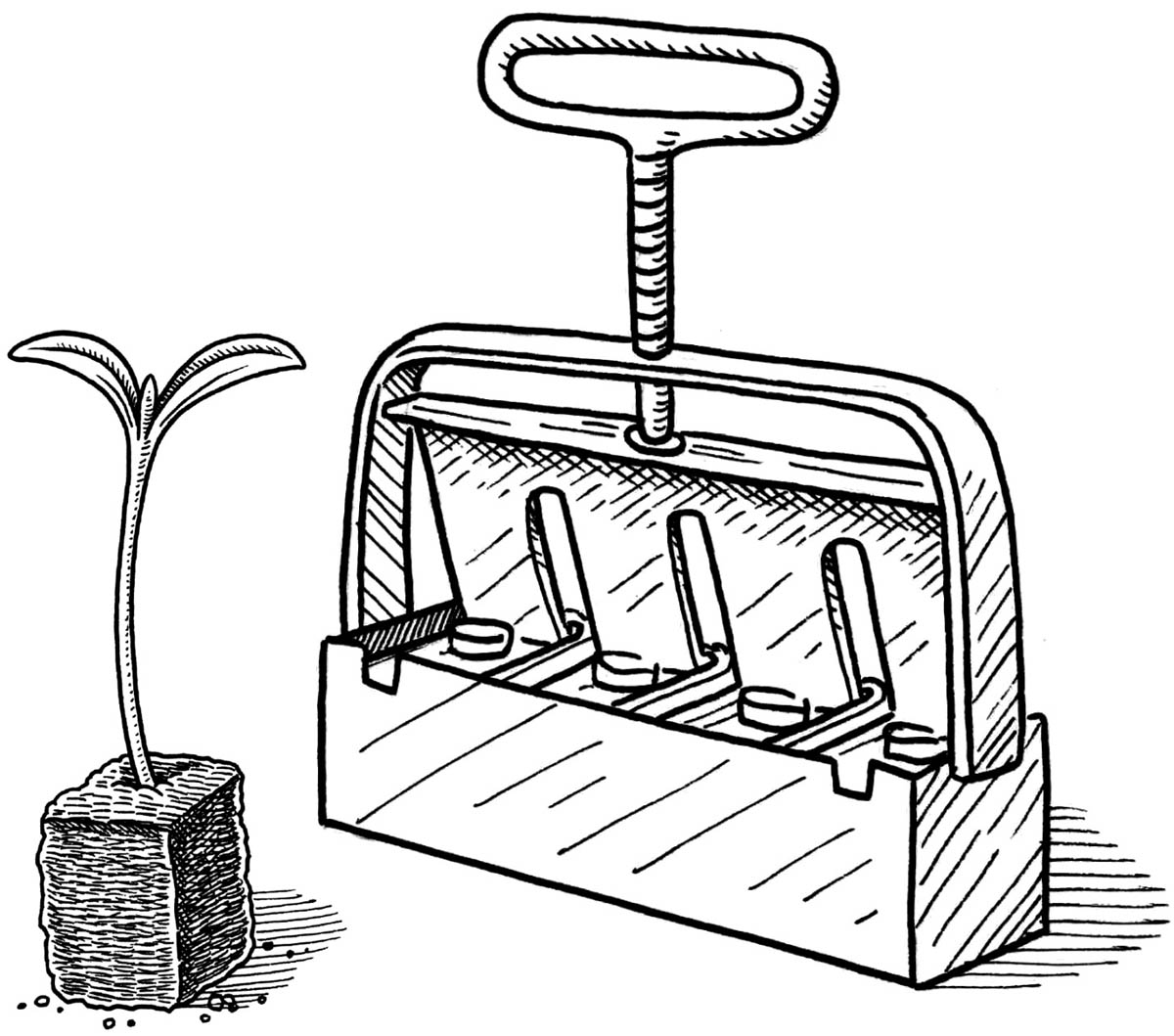

A device called a soil blocker can make a few worm castings go a long way. This small, hand-operated plastic or metal tool enables you to compress a potting soil mixture into various sizes. Block forms can range from 3⁄4" (1.9 cm) to 4" (10.2 cm). The size you choose will depend on the seed you are planting and the length of time you intend to grow the seed before transplanting. The top of the block will have either an indentation to drop a seed into or a deep center hole for inserting a root cutting or transplant. Make up a wetter than normal potting mix containing about 25 percent worm castings, and compress it into the soil blocker. Plant a seed in the resulting block; keep it moist, as you would a peat pot. When the young plant is ready to transplant, insert the soil block into its planting hole and the young plant will take off without undergoing the normal transplant shock. When a plant is started in a traditional container, its roots will circle around the container wall, and transplant shock can occur when the seedling goes into the ground. In contrast, soil blocks are placed on trays with air space between the block walls. Shock is reduced because the plant roots grow to the edge of the soil wall and wait to grow further until they are either put into a larger soil block or into the ground. Another advantage of starting seeds this way is the environmental savings of not using a plastic pot, especially those that are used once and thrown away into a landfill. And as already mentioned, I do not recommend the use of peat.

Using a soil blocker with a mix of potting soil and worm castings is efficient and prevents transplant shock.

Sprinkle a layer of worm castings about 1/4" deep on the soil surface that supports your potted plants, and water as usual. Repeat every 45 to 60 days. If necessary, remove some of the soil above the roots so that you have room for the worm castings. Let excess water move through the soil occasionally to flush out accumulations of salts, particularly if you have hard water. And remember, don’t use softened water on your plants; it contains other salts that do harm.

In your garden, sprinkle worm castings along the bottom of your seed row or throw a handful of castings into the hole when you are transplanting. The adjacent soil will dilute excessive salt concentrations in the castings. It is perfectly natural for vegetable seeds present in the vermicompost to sprout. Simply pull these sprouts as you would pull weeds.