Chapter Twenty

Pluralism and American Piety

CHRISTIANITY WAS TRANSFORMED AND RENEWED by crossing the Atlantic. Not in Latin America, which until recently was a replica of the superficial piety of Europe (see chapter 22). But in North America, Christianity encountered invigorating new conditions.

Even in early times, Europeans marveled at the high level of religious commitment in America, despite the fact that it was very low by today’s standards. In 1776, on the eve of the Revolutionary War, only about 17 percent of those living in one of the thirteen colonies actually belonged to a religious congregation1 ; hence more people probably were drinking in the taverns on Saturday night than turned up in church on Sunday morning. As for this being an “era of Puritanism,” from 1761 through 1800, a third (33.7 percent) of all first births in New England occurred after less than nine months of marriage, and therefore single women in Colonial New England were more likely to engage in premarital sex than to attend church.2

Nevertheless, in 1818 the radical English journalist William Cobbett (1763–1835) was astonished by the number and size of the churches in American villages: “and, these, mind, not poor shabby Churches, but each of them larger and better built and far handsomer than Botley Church [the lone church in his English village], with the church-yards kept in the neatest order, with a headstone to almost every grave. As to the Quaker Meeting-house, it would take Botley Church into its belly, if you were first to knock off the steeple.”3 A few years later the famous French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) noted that “there is not a country in the world where the Christian religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men than in America.”4 At midcentury, a Swiss theologian observed that attendance at Lutheran churches was far higher in New York City than in Berlin.5

If European visitors were amazed at American religiousness, Americans who travelled in Europe were equally amazed at the lack of religious participation they observed there. For example, Robert Baird (1798–1863), the first major historian of American religion, reported in 1844, after spending eight years on the continent, that nowhere in Europe did church attendance come close to the level taken for granted by Americans.6

But why? Why did America become so well churched? What are the effects of the extraordinary religious pluralism that exists in the United States, and how do these many faiths manage to coexist peacefully? These questions are the focus of this chapter.

Colonial Pluralism

THE VERY LOW LEVEL of religious participation that existed in the thirteen colonies merely reflected that the settlers brought with them the low level that prevailed in Europe. Keep in mind that few of the colonists were members of intense sects who had come to establish Zion in America—Puritans did not even make up the majority of persons aboard the Mayflower. That the Puritans ruled Massachusetts, imposing their morality into law, has tended to mask the fact that, even in Massachusetts most colonists did not belong to a church congregation—only 22 percent did belong.

In addition, some of the larger denominations, such as the Anglicans and Lutherans, were overseas branches of state churches and not only displayed the lack of effort typical of such establishments, but were remarkable for sending disreputable clergy to minister to the colonies. As the celebrated Edwin S. Gaustad (1923–2011) noted, there was constant grumbling by Anglican vestrymen “about clergy that left England to escape debts or wives or onerous duties, seeing [America] as a place of retirement or refuge.”7 The great evangelist George Whitefield (1714–1770) noted in his journal that it would be better “that people had no minister than such as are generally sent over... who, for the most part, lead very bad examples.”8

Finally, most colonies suffered from having a legally established denomination, supported by taxes. The Anglicans were the established church in New York, Virginia, Maryland, North and South Carolina, and Georgia. The Congregationalists (Puritans) were established in New England. There was no established church in New Jersey and Pennsylvania and, not surprisingly, these two colonies had higher membership rates than did any other colony.9 Therein lies a clue as to the rise of the amazing levels of American piety. Recall from chapter 17 that Adam Smith explained that established religions, being monopolies, inevitably are lax and lazy and that ever since Constantine embraced the faith, European Christianity has suffered from a lack of effort to arouse popular commitment. But these lazy monopolies did not survive in the United States.

Following the Revolutionary War, state religious establishments were discontinued (although the Congregationalists held on as the established church of Massachusetts until 1833), and even in 1776 there was substantial pluralism building up everywhere (see table 20.1). This increased rapidly with the appearance of many new Protestant sects—most of them being of local origins. With all of these denominations placed on an equal footing, there being no government favoritism, there arose intense competition among the churches for member support. That was the “miracle” that mobilized Americans on behalf of faith with the result that by 1850 a third of Americans belonged to a local congregation. By the start of the twentieth century, half of Americans belonged, and today about 70 percent belong.10

Table 20.1: Number of Congregations in the Thirteen Colonies by Denomination, 1776

Sources: Paullin, Atlas of the Geography of the United States (1932), and Finke and Stark, The Churching of America, 1776–1990 (1992; 2005).

Throughout the nineteenth century, there was widespread awareness that it was competitive pluralism that accounted for the increasingly great differences in the piety of Americans and Europeans. The German nobleman Francis Grund (1798–1863), who arrived in Boston in 1827, noted that establishment makes the clergy “indolent and Lazy,” because

a person provided for cannot, by the rules of common sense, be supposed to work as hard as once who has to exert himself for a living.... Not only have Americans a greater number of clergymen than, in proportion to the population, can be found on the Continent or in England; but they have not one idler amongst them; all of them being obliged to exert themselves for the spiritual welfare of their respective congregations. The Americans, therefore, enjoy a three-fold advantage: they have more preachers; they have more active preachers, and they have cheaper preachers than can be found in any part of Europe.11

Another German, the militant atheist Karl T. Griesinger, complained in 1852 that the separation of church and state in America fueled religious efforts: “Clergymen in America [are] like other businessmen; they must meet competition and build up a trade.... Now it is clear... why attendance is more common here than anywhere else in the world.”12

Pluralism Misconceived

ODDLY, THE RECOGNITION THAT competition among religious groups was the dynamic behind the ever-rising levels of American religious participation withered away in the twentieth century as social scientists began to reassert the charges long leveled against pluralism by monopoly religions: that disputes among religious groups undercut the credibility of all, and hence religion is strongest where it enjoys an unchallenged monopoly. Thus Steve Bruce claimed that “pluralism threatens the plausibility of religious belief systems by exposing their human origins. By forcing people to do religion as a matter of personal choice rather than as fate, pluralism universalizes ‘heresy.’ A chosen religion is weaker than a religion of fate because we are aware that we chose the gods rather than the gods choosing us.”13 Long before Bruce ventured these lines, this view had been formulated into elegant sociology by the prominent Peter Berger, who repeatedly argued that pluralism inevitably destroys the plausibility of all religions because only where a single faith prevails can there exist a “sacred canopy” that spreads a common outlook over an entire society, inspiring universal confidence and assent. For, as Berger explained, “the classical task of religion” is to construct “a common world within which all of social life receives ultimate meaning binding on everybody.”14 Thus, by ignoring the stunning evidence of American history, Bruce, Berger, and their many supporters concluded that religion was doomed by pluralism and that to survive, therefore, modern societies would need to develop new, secular canopies.

But Berger was quite wrong, as even he eventually admitted quite gracefully (see chapter 21). It seems to be the case that people don’t need all-embracing sacred canopies, but are sufficiently served by “sacred umbrellas,” to use Christian Smith’s wonderful image.15 Smith explained that people don’t need to agree with all their neighbors in order to sustain their religious convictions; they only need a set of like-minded friends—pluralism does not challenge the credibility of religions because groups can be entirely committed to their faith despite the presence of others committed to another. Thus, in a study of Catholic charismatics, Mary Jo Neitz found their full awareness of religious choices “did not undermine their own beliefs. Rather they felt they had ‘tested’ the belief system and been convinced of its superiority.”16 And in her study of secular Jewish women who convert to Orthodoxy, Lynn Davidman stressed how the “pluralization and multiplicity of choices available in the contemporary United States can actually strengthen Jewish communities.”17

But if they have been forced to retreat from the charge that pluralism is incompatible with faith, critics of pluralism now advance spurious notions about the consequences of competition for religious authenticity. The new claim is that competition must “cheapen” religion—that in an effort to attract supporters, churches will be forced to vie with one another to offer less demanding faiths, to ask for less in the way of member sacrifices and levels of commitment. Here too it was Peter Berger who made the point first, and most effectively. Competition among American faiths, he wrote, has placed all churches at the mercy of “consumer preference.”18 Consumers will prefer “religious products that can be made consonant with secularized consciousness.” For “religious contents to be modified in a secularizing direction... may lead to a deliberate excision of all or nearly all ‘supernatural’ elements from the religious tradition... [or] it may just mean that the ‘supernatural’ elements are de-emphasized or pushed into the background, while the institution is ‘sold’ under the label of values congenial to secularized consciousness.”19 If so, then the successful churches will be those that require no leap of faith vis-à-vis the supernatural, impose few moral requirements, and are content with minimal levels of participation and support. In this way, pluralism leads to the ruination of religion. Thus did Oxford’s Bryan Wilson (1926–2005) dismiss the vigor of American religion on grounds of “the generally accepted superficiality of much religion in American society,”20 smugly presuming that somehow greater depth was being achieved in the empty churches of Britain and the Continent. In similar fashion, John Burdick proposed that competition among religions reduces their offerings to “purely opportunistic efforts.”21

Successful Religious “Firms”

THE CONCLUSION THAT COMPETITION among faiths will favor “low cost” religious organizations mistakes price for value. As is evident in most consumer markets, people do not usually rush to purchase the cheapest model or variety, but attempt to maximize by selecting the item that offers the most for their money—that offers the best value. In the case of religion, people do not flock to faiths that ask the least of them, but to those that credibly offer the most religious rewards for the sacrifices required to qualify. This has been demonstrated again and again. For a variety of reasons, various Christian churches have greatly reduced what they ask of their members, both in terms of beliefs and morality, and this always has been followed by a rapid decline in their membership and a lack of commitment on the part of those who stay. Thus were the dominant American denominations of 1776 overwhelmed by the arrival on the scene of far stricter denominations such as the Methodists who had, by 1850, become by far the largest denomination in America. Then, by the dawn of the twentieth century, the Methodists had greatly reduced the moral requirements to be a member in good standing and their decline already had begun. Meanwhile, the Southern Baptists continued to be an unflinchingly “expensive” religion and soon replaced the Methodists as the nation’s largest Protestant body—and so they remain.22

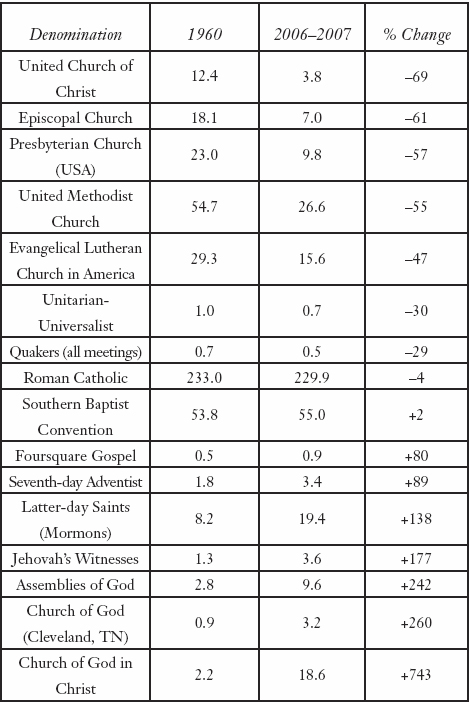

This pattern of differential success shows up overwhelmingly in table 20.2, which reports changes in the membership of various American denominations from 1960 through 2006 or 2007 (depending on the most recent statistics reported by a denomination). To take account of population growth, membership is calculated as per one thousand U.S. population that year. Another way to interpret the statistics is as reflecting changes in each group’s “market share.” The denominations at the top of the table are the very liberal Protestant bodies that the media often identify as the “mainline,” albeit that they might more accurately be identified now as the “sideline.” Each of these bodies is notable for discarding traditional Christian teachings and for asking little of its clergy and members—the Episcopalians long tolerated John Shelby Spong, an extremely vocal atheist, as a bishop. Since 1960, each of these denominations has suffered a catastrophic loss of members. Thus, in 1960 there were 12.4 members of the United Church of Christ (formerly the Congregationalists) per one thousand Americans; in 2007 they had only 3.8 members per thousand. The Episcopalians fell from 18.1 to 7.0 and the Methodists from 54.7 down to 26.6. It also is significant that the “cheapest” American religious body, the Unitarian-Universalists, has never been able to attract a significant following and is declining nonetheless.

Midway down the table is the Roman Catholic Church. For all of its travails during this era, it has declined by only 4 percent. Meanwhile, the huge Southern Baptist Convention managed to grow by 2 percent.

From there on down the table are denominations that embrace traditional beliefs and impose high standards of morality and commitment on both clergy and members. Each of these groups has grown at a prodigious rate. Perhaps no Christian denomination asks as much of members as does the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the Witnesses continue to grow rapidly. Similarly, the Assemblies of God grew by almost two-and-a-half times during this period (and grew even faster worldwide). Having increased at a rate in excess of 700 percent, the very conservative, African-American Church of God in Christ is now much larger than any of the liberal denominations except the Methodists and likely will pass them within another decade or two. Even so, some of the most rapidly growing Christian groups are not included in the table. For example, the Association of Vineyard Churches didn’t exist in 1960, having been founded in 1978, and today has more than fifteen hundred churches worldwide. Indeed, the most robust set of American congregations are omitted from the table for lack of trend statistics—the large and very rapidly growing body of evangelical, nondenominational churches, very few of which even existed in 1960. These churches now enroll about 34 Americans per thousand population,23 making them more than half the size of the Southern Baptists. Claims that these nondenominational churches, especially the megachurches among them, thrive by going “light on doctrine and sin,”24 are utterly false. These are demanding churches.25

Table 20.2: Some Growing and Declining American Denominations

American Members per 1,000 U.S. Population

Sources: Yearbook of American Churches, 1962, and Yearbook of American

and Canadian Churches, 2008, 2009; Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses, 1961.

Conclusion: competition does not reward “cheap” religion.

This is further demonstrated by the results of decisions made at the Second Vatican Council meetings of the Roman Catholic Church during the early 1960s. Among the many actions taken by the bishops were some that greatly reduced the sacrifices required of nuns and monks. For example, many orders of nuns were allowed to abandon their elaborate garb and wear clothing that does not identify them as members of a religious order. Other council actions revoked rules requiring many hours of daily prayer and meditation in convents and monasteries. These and many similar “reforms” were widely hailed as inaugurating a worldwide renewal of the religious orders. Within a year, a rapid decline ensued. Many nuns and monks withdrew from their orders. Entry rates plummeted. The orders shrank. Thus, the number of nuns in the United States fell from 176,671 in 1966 when the council adjourned, to 71,487 in 2004, and the number of monks fell by half. Similar declines took place around the world. These declines have nearly always been explained (usually by ex-nuns who now are professors of sociology)26 as the result of placing too severe demands upon members of the orders—demands incompatible with modern life. But what is truly revealing is that the process has turned out to be reversible. Some religious orders reinstated the old requirements and some new orders were founded that again ask for high levels of sacrifice. These orders have been growing!27 So much for the claims that the levels of sacrifice were too high.

But it is not merely that more demanding religious groups attract and hold more members than do the less demanding faiths. They recruit them! That is, their members are sufficiently committed so that they seek to bring others into the fold, something members of the less demanding faiths seem reluctant to do. Nearly half of all members of the various evangelical Protestant denominations report that they have personally witnessed to a stranger within the past month and two-thirds have witnessed to friends.28

Finally, critics of pluralism like to cite Islam as proof that monopoly faiths are the strongest, pointing out the high levels of religious belief and participation present in most Muslim societies. All this reflects is that, just as most Muslims think Christianity is monolithic, most Christians have the equally erroneous notion that Islam is monolithic. In fact, there is an immense amount of variation within Islam—not just major divisions such as that between Sunnis and Shiites, but even at the level of local mosques.29 That is, within towns having, say, four mosques there will be as much variation among them as there is within American towns having four Protestant churches. The reason for this degree of pluralism in Islam arises from the fact that “individual clergy (ulama ) must raise their own revenues via active recruitment of members; their career livelihood depends upon vigorous participation of the faithful.”30 Hence, competition among the local mosques helps to generate high levels of religiousness in Islam just as it does within American Christianity. In addition, of course, most Muslim nations labor under very repressive governments that exert considerable pressure on citizens to display public piety.

Mystical America

IT IS WELL-KNOWN THAT Americans have unusually high rates of religious participation and that the majority embrace traditional Christian beliefs. For example, more than half contributed $500 or more to their church during 2006 and 18 percent gave $2,000 or more. Excluding grace said before meals or prayers recited in church, a third of Americans pray several times a day and half pray at least once a day. As for beliefs, 82 percent believe in heaven; 75 percent believe that Hell exists; 70 percent believe in demons; 53 percent expect the Rapture, and only 4 percent say they do not believe in God.31

But there is a very neglected aspect of American religion that only recently has begun to be examined: mystical or religious experiences. Efforts to examine such experiences back in the 1960s in the first major surveys of religion in America were thwarted when several prominent theological consultants objected on grounds that mysticism is so rare and constitutes such bizarre behavior that it was pointless to devote questions to it and, worse yet, to ask about it would offend most respondents.32 The theologians were utterly wrong! The 2007 the Baylor National Survey of American Religion, conducted by the Gallup Organization, asked:

Please indicate whether or not you have ever had any of the following experiences:

I heard the voice of God speaking to me. Yes: 20 percent.

I felt called by God to do something. Yes: 44 percent.

I was protected from harm by a guardian angel. Yes: 55 percent.

Many will try to dismiss the guardian angel finding as a mere figure of speech, a way in which people acknowledge a lucky break. Subsequent follow-ups involving conversations with pastors and many congregants strongly suggest otherwise—that people meant their answer literally. Consider too that 61 percent of Americans say they believe “absolutely” in the existence of angels and another 21 percent think they “probably” exist. No wonder television series such as Touched by an Angel have been so popular. In any event, future Baylor surveys will pursue American mystical experiences in considerable detail.

Pluralism and Religious Civility

IF FOR A LONG time it was widely, if erroneously, believed that pluralism weakens all religions, it also was taken for granted that pluralism must result in religious conflicts, even to the point of warfare and persecution. The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) argued that to maintain public peace and order, the state must thwart all outbursts of religious dissent—at least until such time as humans outgrew their “credulity” and “ignorance” and finally rejected all gods as “creatures of their own fancy.”33 Meanwhile, there must be a single, authoritative church under control of the sovereign. A century later David Hume (1711–1776) agreed. Only where there is a monopoly religion can there be religious tranquility. For where there are many sects, the leaders of each will express “the most violent abhorrence of all other sects,” causing no end of trouble. Therefore, wise politicians will support and sustain a single religious organization and repress all challengers.34 These views seemed consistent with the religious history of Europe and its legacy of hatred, massacres, and war. But, on closer inspection, it can be seen that it was the effort to repress challengers that produced all this bloodshed.

As usual, Adam Smith (1723–1790) got it right by standing the conventional argument on its head: religious conflicts stem not from too many religious groups competing in a society, but from too few! Indeed, Smith argued that his friend Hume had mistakenly supported the most “dangerous and troublesome” situation: a one church monopoly. What was desirable was a:

society divided into two or three hundred, or perhaps as many [as a] thousand small sects, of which no one could be considerable enough to disturb the publick tranquility. The teachers of each sect, seeing themselves surrounded in all sides with more adversaries than friends, would be obliged to learn the candour and moderation which is so seldom to be found among the teachers of great sects.... The teachers of each little sect, finding themselves almost alone, would be obliged to respect those of almost every other sect, and the concessions which they would mutually find it both convenient and agreeable to make to one another... [would result] in publick tranquility.35

To put Smith’s insights more formally: Where there exist competing religions, norms of religious civility will develop to the extent that there exists a pluralistic equilibrium. Norms of religious civility exist when public expressions and behavior are governed by mutual respect. A pluralistic equilibrium exists when power is sufficiently diffused among a set of competitors so that conflict is not in anyone’s interest.

Keep in mind too that civility refers to public settings—each religious group remains free to express its exclusive grasp of truth and merit in private, and many will do so. Thus, for example, traditional Jewish groups continue to teach that Jesus was not the promised messiah and most Christian groups continue to teach that the Jews erred in rejecting Jesus, but in the United States both Christians and Jews affirm the legitimacy of one another and in public each is careful to give no offense. In fact, it has become very common for Christian and Jewish clergy to participate together in public ceremonies during which all religious utterances are limited to those acceptable to both. So, Smith was right. Of course, the rise of religious civility in America took several centuries, during which there was a great deal of “publick disorder” and suffering.

Conclusion

PLURALISM HOLDS THE KEY to the vitality of American religiousness as well as to the development of religious civility. One might think that economists long ago would have pointed this out to their colleagues in sociology who were so enamored of the strength of monopolies, since Adam Smith had laid out the whole analysis with such clarity long ago. Trouble is that until very recently, economists were so little interested in religion that the entire chapter on these matters in Smith’s classic The Wealth of Nations was (and is) omitted from most editions.36 It was not until I began working out the stimulating effects of pluralism on my own that someone suggested I read Smith—and I found this puzzling because initially I could find nothing on the topic in the readily available editions. Today, colleagues in economics find my emphasis on pluralism and competition fairly obvious, while many sociologists of religion continue to believe that I am obviously wrong—that competition harms religion and that I have been misled by inappropriate analogies with capitalism. Of course, the great majority of social scientists pay no attention to such peripheral matters, being secure in their knowledge that religion is doomed and soon must vanish.