1

Origins and Objectives of Yoga

The origin of Yoga goes back to the period of Vedic civilization, probably five thousand years before Jesus Christ. Nevertheless, rock inscriptions in the form of yogic postures discovered in 1952 at Addaura, on Sicily, seem to bear witness to the presence of āsanas (yogic postures) in the Mediterranean between 10,000 and 15,000 BCE. More recent remains in India, dating from 2475 to 3000 BCE, attest to the fact that yogic postures were known there during the Vedic period. Discoveries made in Mohenjo-Daro, in modern-day Pakistan, confirm this theory.

Reflections on the Sacred Texts of India

The sages of India consider the Vedas and the Tantras to be the two arms of the divine power supporting the universe. Dating back to time immemorial, emerging out of India’s prehistory, and the source of numerous sacred texts, the Vedas are not of human origin. They are neither the fruit of intellectual speculation nor the expression of dogmatic or ritualistic beliefs. Symbolically, they emanate from the mouth of Brahmā, one of the three Hindu gods. The Tantras, on the other hand, which are almost as ancient, come from Śiva, the god of destruction and reproduction.

Fig. 1.1. The Addaura Cave on Sicily

The Vedas, source of all Yoga, were “seen” by Brahmā, the first rishi and Yoga guru. The different aspects of Vedic Yoga were then explained by Viṣṇu, while Śiva, often regarded as the actual father of Yoga, gave it a new and detailed interpretation. Vedic Yoga was collected in the Tantras to become Tantric Yoga. The original Vedic exposition of Yoga is thus detailed in the Upaniṣads, while Tantric Yoga is fully explained in the Tantras. The rishis’ various interpretations of Yoga have been collected in the Itihāsas and the Purāṇas. Advanced understanding of Yoga therefore is conveyed via a study of the Vedas. The term Yoga is mentioned in the Mantra Veda, while its essence is integrated into the Gāyatrī Mantra of the Ṛigveda.

The complete experience of the Vedas is a revelation of all possible knowledge. In theological terms, it corresponds to the experience of the omniscience of Brahmā. The Vedas therefore contain the quintessence of all scientific and spiritual knowledge, every area of wisdom accessible to humans:

- Ultimate knowledge of the Supreme Being (asamprajñāta samādhi)

- Supraconscious knowledge of the Supreme Being and of objects at different levels (samprajñāta samādhi)

- Cognitive realizations at the suprasensory level (dhyāna)

- Superior intellectual knowledge of spiritual and physical sciences

- Knowledge of all sensory perceptions

Tradition refers to the Vedas as śruti, a term that implies a sound or visual revelation perceived in a transcendental state of mental concentration (dhyāna or samādhi). According to this same tradition, all existing truth can be revealed to anyone empowered to receive it. This obviously doesn’t mean that a person who can hear or see a truth thus revealed is the creator or the inventor of it. The genius of a Newton or an Einstein does not make these scientists respectively the creators of gravitation or cosmic relativity. They can only claim to have discovered and enunciated the mechanisms that govern these two physical phenomena. Similarly, in their supraconscious vision (dhi) of the Vedas, the rishis or seers received a limited understanding of the elements of life, the mind, and matter.

A gigantic magnum opus of a billion verses, the Vedas were revised by the sage Vyāsa,*3 who abbreviated them in eighteen parts amounting to four hundred thousand verses. The texts of the Brāhmaṇas, which were taken from the original Vedas and are assumed to be encyclopedic, were written by the rishis from the Vedic mantras, written components of the Samhītās (collection of scriptures) of the Vedas. The Brāhmaṇas facilitate the comprehension of the Vedas. They cover subjects related to social or political matters as well as the religions of ancient India.

The Brāhmaṇic scriptures are also made up of the Upaniṣads, of which 108 are available today. These scriptures explain Yoga and the way of obtaining a state of supreme consciousness that corresponds to the direct realization of the Absolute (Brahman). They explain the nature of the mind as well as the pranic forces or the nāḍīs that are traces of subtle kinetic currents.*4

There are several further studies on the scriptures called the Smṛiti Samhītās, which deal mainly with questions of law, traditions and customs, and codes of behavior. Also of note is a discourse on the practice of divine love, of which the most known presentation is that of Angira, entitled Daiva Mīmāmsādarśana.

We should also mention the six darśanas. In the absence of an equivalent term, darśana is most often translated as “philosophy,” although, strictly speaking, it means “point of view.” A better translation might be “paradigm demonstration,” in the epistemological sense of the word. Darśana suggests the direct experience of the physical, mental, and spiritual world, as well as the acquisition of knowledge by research, study, experiment, and intuition. Of the six “points of view”—that is to say, the Vaiśeṣikadarśana of Kanada, the Nyāyadarśana of Gautama, the Samkyadarśana of Kapila, the Pūrva Mīmāmsādarśana of Jaimini, the Vedāntadarśana of Vyāsa, and the Yogadarśana of Patañjali†16—the Yogadarśana is undoubtedly the most widespread in the West. The aphorisms of Patañjali’s classical work, dedicated to the study and practice of Yoga, were introduced into Europe by the German philosopher Schopenhauer in the nineteenth century.

The attempt to date the Vedas has led to many hypotheses by various erudite people. They refer on the one hand to the rich oral tradition and to the exegesis of Hindu scriptures, and on the other hand to conclusions (often hasty and conjectural) based mainly on archaeological excavations. The Western conception of time is generally limited to paleontological and archaeological discoveries, which define our history as dating back eight thousand years. However, cosmological conclusions in India open up much vaster horizons.

These ideas would seem purely fictitious were it not for the fact that we have long been aware of the innovative role of Indian culture in many domains, notably in arithmetic and astronomy. For example, one could quote the rishi Kanada, whose ideas foreshadowed atomic theory and considered light and heat as two forms of the same primordial substance. Incidentally, it is the same Kanada whose description of Kuṇḍalinī as Supreme Power, with reference to his global vision proclaims that it “shines like ten million suns and is bright and cool like ten million moons and splendorous like lightning” (Tārārahasya).

Is the teaching of Indian sacred texts really more disturbing than that of recent astrophysical and subatomic advances, which for approximately the last two centuries have tirelessly expanded the limits of the universe and its contents? In the West physical science has made great progress since the time of Democritus, the first man in history to put forward a theory of atoms, and even more progress since Heraclitus, who considered the universe to be an incessantly moving world and was thus in direct opposition to the spiritual father of contemporary science, Parmenides of Elea. Known by Plato as the “Great One,” Parmenides’ holistic understanding of “being is what is, nonbeing is what is not” was singularly close to Vedic monism.

Many erudite paradigms have been introduced since Aristotle placed the earth in the middle of the universe and since the emancipating revolution of Copernicus, who allowed our Western ancestors, ignorant or neglectful of the rest of the universe, to break the planetary preeminence in which they believed they lived.

Moreover, what can be said about the recent increase in the total number of known galaxies—mapped to an astonishing 260 thousand— other than it abolishes the myth of a solar system that enjoys a unique status? And what can be said of the dizzying idea put forward by today’s scientists of an expanding flat universe, evolving cyclically, with a diameter of 1,600,000,000 km, which, since the last cataclysm, would be several billion years old? Or, in an increasingly surprising “multiverse” revealed by NASA’s recent and equally amazing study, indicating that our own galaxy gives shelter to 46 billion planets with sizes that are similar to that of our planet Earth?

What can we expect from research into a truth that, in the light of these recent discoveries, has drifted into the notion of a macrocosm that seems to be fused with the microcosm? Do not the potential variants of the theory of strings and superstrings, which aim to reconcile general relativity and quantum mechanics, open new perspectives on the current instrument-based research, which is imprisoned in the four human dimensions—three spatial and one temporal—a limitation that forever prohibits access into a universe composed of ten or eleven dimensions, if not more? A pragmatic mind will suggest that all these facts, proven or supposed, cannot really disturb the familiar oasis of which an ordinary person’s life consists.

The wisdom of Indian holy writings is not the expression of an intellectual ideology that refutes all reality and the world. Nor is it, moreover, the reflection of an anthropogenic principle that would not concede any particular interest to the universe except to its materially observable aspects.

In the vision of the rishis, time is eternal. That is to say, time is without end, consisting of a past with no beginning and a future with no end. The creation of the cosmos is a repetitive, tangible manifestation of the Absolute. In the succession of cycles (manvantara*5), time consists of the inseparable phenomena of creation and destruction that characterize cosmic evolution. Each cycle is endowed with a cosmic progenitor (Manu). In the current era (yuga) he is called Vaivasvata. In his role as the prototype of humanity, this progenitor corresponds approximately to the Hebrew tradition of Adam.

Probably inspired by Hermes Trismegistus, who asserted in the Book of the Twenty-four Philosophers that “God is an infinite sphere, the center of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere,” Pascal, and probably many others with him, duplicated that concept, but substituted the universe for God at the center of their thesis and declared: “The universe is an infinite sphere, the center of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere.”

Hindu cosmology postulates the existence of an underlying static, causal principle endowed with the power to “will” and to express the dynamic aspect of a static eternal reality. Following this view, whatever manifests in the cosmos constitutes the circumference that is everywhere, while the center (the unmanifested) upon which it depends is nowhere. In this paradigm, one motionless Prime mover is the origin of all cosmic manifestation and its amazing biodiversity and changes.

The dissolution of the cosmos coincides with the beginning of a period of nonmanifestation, which, in symbolic terms, is neither more nor less than a return to the supreme source—Brahman, or the Absolute. Out of this Absolute a new manifestation then emerges. This alternation is described allegorically as “the days and nights of Brahmā.” According to recent interpretations of ancient writings, notably the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, the duration of “a day of Brahmā,” or kalpa, is determined with a degree of arithmetical precision: the philosopher O. V. Krishnamurthy asserts that this duration, which cannot be conceived by thought, is 4,320 million years. These esoteric calculations divide space-time into fourteen periods (manvantara) and seventy-one ultimate subdivisions (Mahā Yuga), each one consisting of four phases: Satya Yuga, Treta Yuga, Dvapara Yuga, and lastly Kali Yuga, the current period, which will last 432 thousand years, which, in symbolic terms, is neither more nor less than a return to the supreme source—Brahman, or the Absolute, the thrice great (sat cit ānanda).

In ancient Greece and Rome, this cosmological order corresponded to the ages of gold, silver, bronze, and iron, glorified by, among others, the poet Virgil:

Once more the great order of the centuries begins. Already a new race is descending from the lofty sky. Then the golden race will appear for the entire world.

As with the kalpa, this unimaginable “day of Brahmā,” which comes after the passing of a cosmic night, is followed by a corresponding period. Brahmā is himself followed by another Brahmā in an infinite cycle, once again inconceivable for the human imagination. . . .

At the frontier of experimental science, a number of important contemporary scientists glimpse another reality than that which is accessible today. Thus does the physicist Schrödinger, author of several philosophical works and an adept of the monist doctrine, invoke the Vedas in order to explain his concept of the world. For his part, Ilya Prigogine, Nobel Laureate for Chemistry in 1997, mentions “the possibility of an eternal recommencement of an infinite series of universes.”*6

In the book by Fred Alan Wolf, Taking the Quantum Leap (Harper and Row, 1989). Richard Phillips Feynman, one of the most influential physicists of the last century, compares the subtle mechanisms of our individuality to an atomic dance similar to the cosmic dance of Śiva: “Atoms enter my brain, perform a dance, and then they exit; forever new atoms, but forever the same dance.” The same thing is said by Fritjof Capra, a philosopher and theoretical physicist, in his preface to The Tao of Physics (Shambhala, 1975).

In a scientific study by Sir Roger Penrose, Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe, the author certainly did not disappoint his learned peers regarding the “extraordinary”: he describes the unfathomable origins of a cyclic cosmos by asserting that “the Big Bang is both the end of one eon and the beginning of another.”

At the risk of giving superficial consideration to a subject many Western and other researchers have investigated for decades, it seems necessary to briefly review the controversy that exists in an academic world that favors theory over pragmatic research and logic over intuitive introspection.

It is not improbable that the Vedas, which are the first known writings, are much older than the age proposed by Western researchers, who too often demonstrate condescension instead of humility and a priori approaches rather than the objectivity that is the responsibility of the scientific mind. In this way their claimed objectivity has suffered from various handicaps: adherence to a religion supposed to have the monopoly on truth; privileged participation in a culture known for its technological prowess; adherence to a society that has bet on material progress for its salvation; inheritance of a civilization with a glorious past and, believing itself superior in every respect, possessed by the mission to conquer and dominate.

It is regrettable that too often the objectivity of Western intellectuals has been unable to take into account the influence of Hindu thought, though it has been well documented, in particular by the philosophers of Ancient Greece, the so-called cradle of Western civilization.

We have been given due warning about this inappropriate feeling of superiority in many ways, including through the false interpretation of the Sanskrit term āryan (virtuous, noble) by Max Müller.*7 In 1853, this German orientalist introduced the term into the West to designate a particular race and its language. Faced with lively criticism from contemporary intellectuals and historians, Max Müller was forced several years later to do his mea culpa for his thesis, the interpretation of which, though not intentionally, carried in its bosom the seed of a regrettably grievous racism. But it was too late, the evil was done, and, like any calumny that can never truly be effaced, the thesis of an Aryan race rapidly took root in several countries, in particular in the heart of German nationalism, which found in it an opportunity to promote its ideology of white supremacy. This ended in the barbarism we know about, the immolation of several million human beings.

Another reason for the depreciation of Hindu civilization resides in the theory of a supposed Aryan invasion of Sanskrit-speaking “Indo-European” northerners via Central Asia. Between 1500 and 1200 BCE these white-skinned peoples are supposed to have invaded an India that was then inhabited essentially by Dravidians and groups of people from the Indian southern peninsula who had brown skins and were considered inferior. The theory of an invasion by Aryan Vedic people seems to present the only serious proof in a doubtful or malevolent interpretation of certain Hindu writings, notably the Ṛigveda. However, this text refers in fact to a racial mixture instead of what one would expect—a description of an alleged struggle of light-skinned against dark-skinned people. This is a strange assertion if one considers that this same Ṛigveda indicates that birth cannot be considered as identifying one who is “Aryan”!†17

The theory of an Aryan invasion seems to crumble following recent archaeological discoveries and cartography, established with the aid of satellites, of the Saraswati River. These evidence the continuity of the Vedic and Saraswati civilizations. In India, the absurdity of the hypothesis of an Aryan invasion has been set out by a particular circumstance, invoked by great thinkers such as Jandhyala B. G. Tilak, Dayananda Saraswati, as well as one of the great names in contemporary spiritual thought, Sri Aurobindo. According to the Vedic writings they invoke, the supposed Aryan invaders mention the names of no religious sites outside of India; they only glorify existing religious sites like the Ganges River, Varanasi, and so on.

Max Müller’s thesis, according to which the birth of the Vedic culture dates back to 1500 BCE, thus collapses. According to many intellectuals in India, the date would instead be between twelve thousand and eight thousand years before the Greco-Roman world and the era of Christianity. As a result, is it not plausible to affirm that the ideological justification of the British invasion of the Indian continent, as well as the cultural North-South tensions that would later follow in India, are without doubt the fruit of these false interpretations? Moreover, we can only deplore the tamasic (inertial) passivity of the Brahmin scholars who adhere, in overwhelming silence or guilty complicity, to these mistaken ideas and thus endorse hasty and irresponsible conclusions drawn from a disastrous theory.

We should also say a few words about the term Hinduism, which is linked to a Vedic civilization several millennia old that ran through a complex kaleidoscope of historical, cultural, and spiritual expressions. Although Hinduism is effectively a religion in the conventional sense of the term—that is to say with texts, rituals, and a moral code—it nevertheless distinguishes itself by its immanence, fluidity, resilience, and rare faculty of absorbing all religious dogmas (is there not a work entitled Allah Upaniṣad?). At the risk of sometimes being accused of an extreme tolerance in its timeless aspiration to universality, it is sanātana dharma, the eternal charioteer of the Bhagavad Gītā, the imperishable theme of Hindu thought.

Hinduism is then characterized by a conceptual epistemology, which, paradoxically as it may seem to the Western mind, embraces at the same time the dual and the nondual, along with other seemingly contradictory aspects: monotheistic in proclaiming the One-and-All doctrine; polytheistic when venerating 300 million deities; pantheistic when identifying Brahman with the universe; and, indeed, atheistic when the jīvanmukta, or “liberated alive,” witnesses an ultimate transcending experience of mokṣa, the merger between ātman and paramātman, the indescribable Absolute sometimes referred to as That.

Hinduism’s attraction for free-thinking, non-Hindu born people is often explained by the absence of dogma and its extreme tolerance, not just a conventional tolerance but an actual respect for all faiths. At the socioreligious level Hinduism proposes a deeper and broader understanding of traditional religious teachings, which at the individual level is reflected by pragmatic approaches that include the inborn dynamism and dormant faculties of the human being. In the daily perception of such an all-embracing vision lies the real source for brotherhood, mutual respect, and natural impulses to help the needy. In daily life’s dilemma of opposed opinions, it successfully brings forth solutions in a holistic paradigm that applies the unwritten principle of complementarity.

Given the complexity of Hinduism, the oldest of all religions, what is surprising to researchers concerned about objectivity, as well as to historians, anthropologists, and theologians, is Hinduism’s unequalled continuity of a sociocultural dynamic, an uninterrupted current with a multitude of ever-changing facets. Rather than propose a servile submission to clerical authority, which not only has no actual possibility of verifying mystical experience but may even find it embarrassing or threatening to its temporal power, the Hindu spiritual quest has no other aspiration than to discover our true identity and to attain liberation from attachment to the illusion of our human condition. Embarking on a spiritual path that does not ignore the misery of the world in which we live, the spiritual seeker begins a quest of becoming acquainted with the experience of yogis and rishis—those exceptional beings who in all times have known how to successfully tackle the possibility of union and supreme bliss with the Divine, which is the ultimate goal of human destiny.

The Yogic Path

In this period of the widespread rediscovery of Yoga, and of Haṭha Yoga in particular, it seems desirable to present briefly and in contemporary terms the tenets and objectives of the yogic path, which offers a vast source of knowledge that constantly has new applications in today’s changing world.

Traditional texts of India present Yoga as the ultimate human attainment. They also explain the exact way of reaching the state of a yogi, the attainment of a primordial consciousness that prepares the way for union with God. Here it is important to keep in mind that the notion of God conveyed by Indian sacred writings differs from that of the Judeo-Christian world. In fact, the term God does not exist in the sacred writings of India, although a multitude of names are given for multiple aspects of God. To avoid misunderstanding, however, we can consider the word God in the Hindu sense as an approximation of what is generally understood in the contemporary Western world.

This same tradition attributes the origin of Yoga to the god Śiva. Originally called Mahā Yoga, it gave rise to a hundred paths of Yoga. The elaboration given by the Upaniṣads concerning the eightfold path of Yoga (Aṣṭānga Yoga) permitted the emergence of new methods and techniques, which are differentiated into two fundamental aspects: the acquisition of powers and the spiritual realization of the individual. In his research, Sri Goswami identified a large number of Yoga variations, some distinct and some similar: twenty-four in the Upaniṣads, forty-three in the Tantras, four in the Yogavasiṣṭa, two in the Rāmāyana, thirty-one in the Mahābhārata, and two hundred and twelve in the Purāṇas.

Of these, only four have survived to this day: Mantra Yoga, Hat. ha Yoga, Laya Yoga (or Kuṇḍalinī Yoga), and Raja Yoga. The last of these, commonly named the “Royal Way,” is related to other paths such as the Yoga of Knowledge (Jñāna Yoga), the Yoga of Devotion to the Divine (Bhakti Yoga), Yoga of Action (Karma Yoga), and many more. Śiva is credited with the following remark on the complementary role of the two principal paths of Yoga: “Without the practice of Raja Yoga, Haṭha Yoga remains incomplete. Without Haṭha Yoga, the practice of Raja Yoga is impossible.”

The way of Haṭha Yoga is both a traditional path of pragmatic spiritual research and a nearly inexhaustible source of human knowledge—a “science of man.” As such, the all-embracing discipline of Haṭha Yoga is a most adequate and versatile “Middle Way” lifestyle, where anyone may faithfully comply with life’s obligations and pleasures while still participating in the spiritual quest of Yoga sādhana (practice).

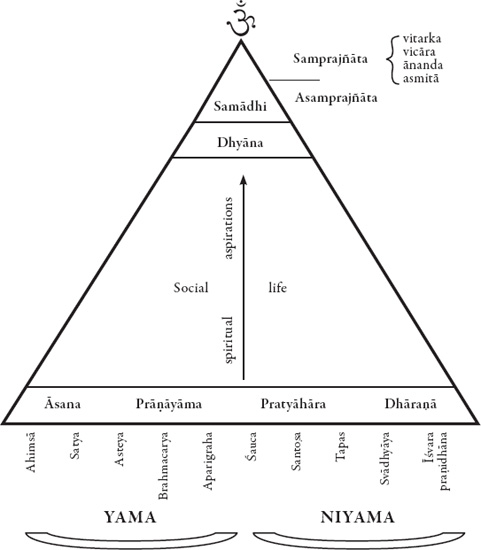

Fig. 1.2. In the Middle Way sādhana, spiritual aspirations help a person to weather the ups and downs of social life, guided by the ethical rules of yama and niyama, which are the essence of all sincere spiritual search.

Inspired by the holistic scheme of life set forth in the Bhagavad Gītā’s triptych of knowledge, action, and love, and following Tantra’s rational philosophy, the Middle Way lifestyle aims at bringing together opposites and, ultimately, transcendentally merging into a sublime state of existence-nonexistence. This ontological proposal challenges the Shakespearian dilemma “To be or not to be.” It affirms the sublime option of: “To be and not to be”!

Haṭha Yoga not only allows a person to find inner peace and to reshape and master the body; it also shapes the senses and the mind into an instrument capable of discovering states of consciousness located beyond the sensory world. It can also provide the means to attain a spiritual peak that is nothing less than the realization of an immanent and transcendent truth, a supreme union, a goal that is characteristic of all forms of living spirituality. In the Hindu tradition, Yoga—with its elements, metaphysics, purifications, and palette of methods—constitutes the bridge that links the human to the Divine.

In the Northern hemisphere, it is above all the āsanas or postures of Haṭha Yoga that retain our attention, most often in the harmless form of physical training, relaxation, sport, or as a therapeutic method, with the limited goal of achieving physical well-being or regaining psychological equilibrium. In truth, though the traditional goal of the psychophysical exercises includes the aims of any physical activity (suppleness, strength, speed, and endurance), Haṭha Yoga offers other advantages such as durable peace of mind, the sense of harmony resulting from awareness of the body, mastery of the breath, and enhancement of mental concentration, which is the essential foundation for mastery of the mind.

It is important to remember that āsanas are only one of eight parts of Haṭha Yoga. Though it is true that this discipline attaches great importance to the body, which is the keystone of our mental and spiritual life, nevertheless this is only one step in the eightfold path considered as sacred. These eight disciplines, which we will consider later in more detail, are:

- Yama—five ethical rules: ahimsā, satya, asteya, brahmacarya, aparigraha

- Niyama—five additional rules: śauca, santoṣa, tapas, svādhyāya, īśvarapraṇidhāna

- Āsana—psychophysical exercises

- Prāṇāyāma—mastery of prāṇa (breath as life force)

- Pratyāhāra—mental process of withdrawing from sensory objects

- Dhāraṇā—first step of mental concentration

- Dhyāna—second step of mental concentration

- Samādhi—apogee of mental concentration

With its eight disciplines, Haṭha Yoga thus constitutes a form of the very ancient Aṣṭānga Yoga, which deals with human beings in all their aspects, manifest and latent, gross and subtle—or, in other words, in all the aspects of our physical, vital, and mental life, including our behavior, will, affective life, and spirituality. Haṭha Yoga also presents unique purification techniques that permit the attainment of an optimal state of purity, toning of the vital force, and improvement of the faculty of perception.

The aim of Yoga, which represents the ultimate exploration in terra incognita, is to invite people in all eras and from all faiths on an introspective adventure that is nothing less than an ontological transmutation, the fusion of humans into beings of excellence—the living ideal, deva deha—referred to in India’s sacred writings.