2

Science and Spirituality

Mysticism is above all an experience that cannot be learned from books. A profound understanding of any mystical tradition can only be obtained when one decides to become actively involved in it.

FRITJOF CAPRA, THE TAO OF PHYSICS

For anyone who sees the Truth as a rich, unexplored country, the choice of pathway to attain it seems secondary. This is without doubt the explanation for the bifurcation during the Renaissance of a path that was common to the East and the West. While the East followed a centripetal way to enlightenment via the elimination of the sensory world through introspection, the West, with its technological discoveries enriched by the theories of the Age of Enlightenment, opted for a centrifugal expansionism designed to lead it to the same Truth, an approach that was in reality one of defiant deviance from past traditions, a kind of materialistic agnosticism.

No one could regret this separation, any more than one could lament a similar division that occurred at the dawn of Western history when we threw in our lot with Aristotle, the father of analytical knowledge and the realism of things, rather than with the other great sage of the time, Heraclitus of Ephesus, for whom the becoming of every being is made of nonbeing. This is the same Heraclitus, presented in Sri Aurobindo’s monograph, and in Osho’s book The Hidden Harmony, as a great mystic, who seemed to recognize the inextricable unity of the eternal and the transitory—“everything flows; nothing remains [still]”—that which is forever yet seems to exist only in this strife and change, which is a continuous dying.

The vocational “Whys” of science started probably with the basic cosmological question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” Granted that things do exist, the corollary question of “How?” inevitably emerges. Assuming an isomorphic confluence between the immensely vast cosmos and the animal kingdom at large, and more particularly human beings, we may next question if there is a possible correlation between today’s prevailing theory of a constantly expanding universe and human evolution. At a more concrete level, we may also wish to plunge into the lesser-known aspects of sleep, a phenomenon shared by all living beings, and which in human life obliterates as much as one-third of our life span. Could this “unproductive” time, which corresponds to a state of nonexistence to the outer world, have a deeper cause and meaning than simply the recovery of biological and mental energies lost during the daytime?

Science, which functions today as a new order of planetary evangelist, most often subjected to utilitarian aspirations, has for a long time brandished the banner of “progress” in opposition to religious obscurantism. At the same time, it proposes an objective explanation of the reality of the world, subject nevertheless to increasingly burdensome investments and a profusion of tools for which the bar in innovation and performance never ceases to be raised. The illusory promise of science experienced a reversal due to the arrival of quantum theory with its lack of deterministic causality, which raises an insurmountable obstacle to objectivist techno-utopians.

We can obviously admit that, in spite of their differences, both the traditional approach and contemporary research ultimately intend to uncover the truth, the former in a union of the human and the Divine, the latter in the technical knowledge of manifestation. This simple postulate could be considered as a “positive synthesis” (along the lines of Hegel’s proposal to reconcile thesis and antithesis into a synthesis).

Two Paths of Evolution

We must nevertheless remember the fundamental distinctions that separate these two paths. The doctrine of Yoga rests on an understanding of evolution that is the opposite of Darwin’s theory. It considers itself holistic and aims at the future of the human, whose nature is hidden and divine. Physical science, on the other hand, as Max Planck said, progresses one funeral at a time. Its purpose is nothing more than a never ending litany of research going in all directions. It generally adheres to Darwinian theory by setting as its intention an experimental and speculative orientation, which is, by necessity, utilitarian.

At the level of methodology, we should especially note that the first of these paths is of an involuting nature, like a spiral movement going toward its center or origin. It refuses or minimizes the impact of materiality and does not depend on any instrumentation other than that of a mind dedicated to introspection, with a duty to avoid the subtle traps of mental projection in its final objective of attaining a state of genuine enlightenment. The ancient science of Yoga does not need any support (scientific or speculative) to explain, confirm, and justify the transcendence of its spirituality.

The second path is still largely linked to an evolutionary foundation, with its exclusive dependence on the intellect, reasoning, and myriad technologies. Its prevailing environment is determined by fierce competition and the attitude of world conqueror that comes from its Western heritage. Globalization opens the doors of the numerous riches of our technological civilization to all the inhabitants of the planet, without regard to social, racial, or other distinctions. It offers thousands of products and services that touch every area of modern life. And, like a child discovering his surroundings, the modern-day Ulysses knows the constant temptation to yield to the Sirens in an ocean of technical marvels whose polymorphous song never ceases.

However, the “truth” of our life constantly challenges logic, reason, and the numerous psychoanalytical methods in fashion in the past or present. The human tragedy resides as much in the fate of our ineluctable physical death as in the feeble means of personal investigation at our disposal, limited as they are to a four-dimensional relativistic continuum and a short life span. We are handicapped by our mental conditioning, modestly equipped with five senses of perception, and limited by an unreliable intuition. While apparatus and instruments for exploring the secrets of matter and the universe push back the limits indefinitely, they are often deployed at high cost and given top priority, despite the major challenges that we face with a suffering biosphere and the enduring social misery that surrounds us. Once we try to understand the true nature of the physical world that shelters us and the mind that we inhabit (and which dominates us), we discover that this approach leaves us at best dissatisfied and at worst powerless.

Although Western physics does not have the same objectives as the esoteric aspect of Yoga, there is no opposition between the two. There are even certain points of convergence and a common language—up to the point, however, of the mystical experience, which is rarely expressed in the ordinary or rational terms of the physical sciences. In these times of globalization, it even appears that the sciences are becoming mystical and researchers of mystical experience becoming more scientific.

In an interview with Renée Weber (titled “Physicist and Mystic—Is a Dialogue Between Them Possible?”), David Bohm, one of the most eminent theoretical physicists of our time, explained that “the positive meaning of mysticism is that the very foundation of our experience is a mystery—an assertion accepted by Einstein himself. He [Einstein] said mystery is the most beautiful thing. In my opinion, however, the term mystic should be applied only to whoever has a direct experience of the mystery that transcends the possibility of what can be described. For the rest of us it remains to be discovered what that means.” Elsewhere he emphasized “the coherence that exists between the physicist and the mystic, the common view of an implicit order and an ocean of energy, which evolves into the creation of space, time, and matter.”

In any event, scientific experimentation is insufficient to know anything other than the parts of the whole. On the other hand, the spiritual mystical experience tends toward a whole, integral understanding of everything. The first is founded on dialectical thought and analysis based on temporal patterns. The second, which claims to be holistic and whose modus operandi is apperception, is interested in an implicit dimension based on nontemporal universal principles.

The Possibility of Fusion

Given the current state of understanding, the fusion of these two fundamentally disparate methods seems hard to achieve. In a universe where we are the hostages of relativity, one could note the fact that, in spite of the current wave of globalization and the forms of rapid communication that accompany it, the level of knowledge on our planet still remains very mixed. Human advances, whether materialistic or spiritual, are never general and homogenous. Progress often varies widely, not only at the individual level, but also in terms of societies or civilizations. Levels of awareness concerning the realities of the world and life values differ in a significant manner. So it is in this pluralistic world of biodiversity, dominated by a materialistic search for happiness, that at the same instant a man lands on the moon, other men in Australia and the Amazon still live in the Stone Age, in total ignorance of the buzz of the technologically oriented world surrounding them. Therefore, is it unreasonable to imagine certain evolved humans on the verge of having an experience that is diametrically opposed to that of the surrounding world, and yet not ignoring it? Sri Aurobindo is said to have claimed that the yogi is a being whose consciousness is situated several thousand years ahead of contemporary humanity.

History teaches that Alexander the Great was the inventor of the term Hindu, which is the origin of the name India today. During one of his expeditions this young disciple of Aristotle discovered the “gymnosophists,” naked ascetics, Hindu ancestors of the elite yogic ascetics today known as naga nagas or naga babas. Since this period of antiquity, Yoga has always been considered the chosen ground of the siddhis, these extraordinary realizations that defy numerous physical and psychological laws and that always surprise us despite rational research into the question. How can we explain yogic phenomenology at a time of modern technological prowess and the communication that accompanies it?

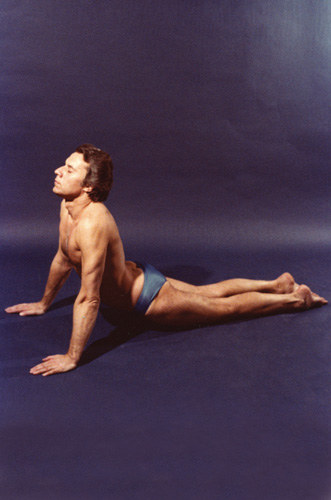

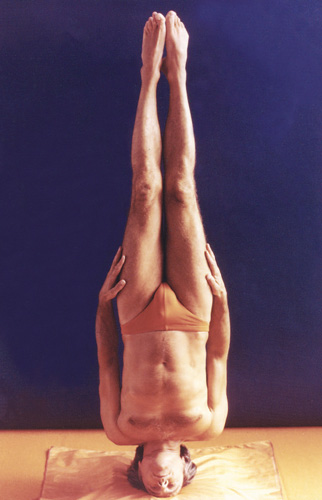

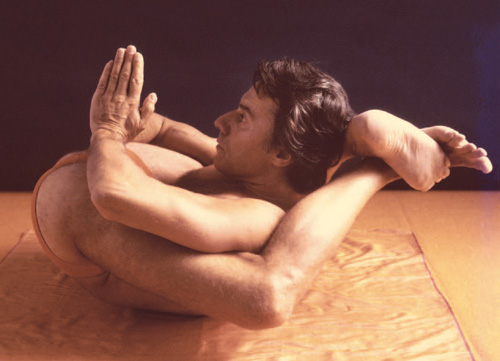

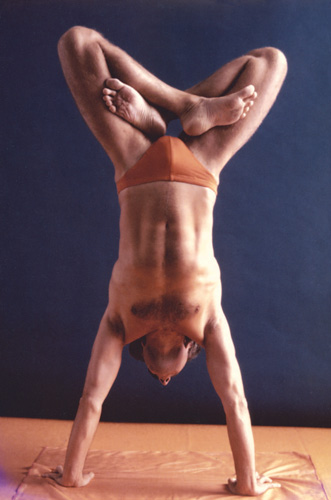

The fundamental purpose of the āsanas is to establish a motionless and comfortable attitude for mental concentration. With grace, control, and purity, the following pictures highlight typical āsanas in standing, prone, inverted, and sitting postures.

Plate 1. Garuḍāsana, Eagle Posture

Plate 2. Pṛiṣṭhāsana, Back Posture

Plate 3. Halāsana, Plow Posture

Plate 4. Baddha Ardha Matsyendrāsana, Ankle-Hold Modified Spinal-Twist Posture

Plate 5. Bhujangāsana, Cobra Posture

Plate 6. Śirāsana, Head-Stand Posture

Plate 7. Ardha Candrāsana, Half-Moon Posture

Plate 8. Baddha Padmāsana, Toe-Hold Lotus Posture

Plate 9. Ekapādāsana, Single-Foot Posture

Plate 10. Dhanurāsana, Bow Posture

Plate 11. Matsyāsana, Fish Posture

Plate 12. Bāhu-pādāsana, (or Dvipādāsana), Arm-Leg Posture

Plate 13. Dvipāda Śirāsana, Double Foot-Head Posture

Plate 14. Hastapadma Vṛiksāsana, Arm-Stand Lotus Posture

In India the yogi(ni) starts the day with a morning prayer and dedicates all forthcoming thoughts and actions to the Divine. The yogi(ni) cultivates a most cherished deva deha ideal by offering all efforts, mental and physical, on the altar of his or her s ādhana. Traditional Haṭha Yoga training commences with a silent confirmation of the morning prayer. The gentle spiritual warrior bows head thankfully to the beloved guru whose know-how, heritage, and presence, living or posthumous, are a continuous source of inspiration.

Plate 15. Bhadrāsana, Happy Posture

Plate 16. Pādaprasāraṇāsana, Sideward Leg-Stretch Posture

Plate 17. Praṇatāsana, Forward Body-Bend Posture

Plate 18. Nataśirāsana, Head-Bend Posture

Plate 19. Maithuna, the sacred act, which allows an all-absorbing union with the beloved one, the devatā.

A concern for objectivity invites suggestion rather than prognostication based on scattered observations and some experienced Indians’ confidentially entrusted secrets. It seems, however, that these issues should be approached with other considerations in mind:

- The incompatible nature of diametrically opposed research programs gives rise to a lack of agreement between the self-proclaimed scientific objectivity of the Western researcher and the transcendence of the tangible world that is proclaimed by the yogi.

- The absence of reference points and criteria of methodological evaluation.

- The empirical limitations of a medico-scientific methodology whose aim is essentially to observe abnormal or pathological behaviors as opposed to the “supranormality” of the yogi.

- The small population of candidates possessing siddhis does not constitute a scientifically valid test sample.

- The yogi’s obvious lack of interest in being submitted to tests that are not designed to help him progress in his sādhana or, in his view, to improve human health.

In addition, yogis are sometimes aware of the experimental criteria used in scientific research, which is often split by competition or is the victim of trends and pressures. Another important barrier, this time to do with cultural history, is the regrettable and notorious arrogance of certain scientists who are infatuated with their academic merits, the fact that they live in a rich country, and, in the worst cases, the belief that they belong to a superior race. Nevertheless, the extraordinary feats of the siddhis surprise us with the mastery and psychic force that is involved.

Why should we thus be surprised at the difficulty of resolving a relationship that, instead of allowing an enriching complementarity, revives the question of the dialogue between the two historically antagonistic, epistemological styles of West and East, tangible and intangible, materialism and spirituality. Rather than lingering vainly on the “miraculous” character of unexplained siddhis, the honest researcher will undoubtedly prefer to be astonished at the age-old capacity for survival of an essentially oral tradition in an impermanent world, a tradition without any institutional structure, which has been able to surmount the vicissitudes of earthly temporal, political, and religious power.

In fact, the present-day dualism between modern scientific or religious thought, on the one hand, and the Hindu tradition, on the other, illustrates the axiom according to which two parallel lines can never intersect. Undeniably, all attempts to bring harmony between cultures or religions are highly laudable, as is mutual tolerance, social justice, or the vision of people enjoying peaceful coexistence. Any effort at rapprochement therefore deserves encouragement so as to develop real solidarity and provide a link allowing the elimination of North-South barriers and filling the ancient chasm that for several centuries has separated the East from the West.