9

Ṣaṭ Karman—Purifications

In any belief, Gnostic or religious, purity is often a central and inseparable topic. Unrelated to the hypocrisy of conformism, it is a real vade mecum for any sincerely religious person, in the broadest sense of the term. It is in fact the virtue par excellence, which particularly makes it possible to realize in any spiritual search the truth stated by Saint Paul according to whom “all is pure for he who is pure.”

Internal Purifications

From time immemorial, yogic literature has affirmed the importance of internal purifications (śodhana) as an essential condition for health, strength, development, and longevity. Inherent in the traditional practice of Haṭha Yoga, it is an established fact that these exercises assist greatly in energizing the whole organism.

A person on the path of Yoga is extremely conscious of the influence of tamas, the inertia that surrounds and inhabits us, which is both ignorance and impurity, whereas the yogi is naturally oriented toward lucidity, power, and mastery, toward an ideal of transcendence. The guru—by definition the dispeller of ignorance—teaches the aspirant how to recognize the many obstacles on the spiritual way, as well as the means to surmount them.

The yogi (or the yogini) can accept purifications from the outset, well knowing the importance of this jewel—purity—which, once fully established, will allow them to achieve the ideal, the emergence of a body similar to that of the gods (deva deha). Just as is implied by the Greek term καθαρòs, which assimilates cleanliness and purity, for the practitioner of Yoga, cleanliness is inseparable from the state of purity that is aspired to and cherished. The purifying act provides structure to life, will on occasions become a ritual, and will inspire the yogi’s quest for purity. The regular and prolonged practice of these purifications often has the spontaneous effect of awakening another need, that of making spiritual offerings. In the language of the poet: “Like the translucent morning dew, the purified soul reflects the light of the Creator.”

Regrettably, the potential wealth of purifications in Yoga is somewhat ignored in our world, a world dedicated to curing diseases, wellbeing, and communication. However, no other school of thought can enrich the conception of hygiene as can Haṭha Yoga, which is a nurturing ground for cleanliness and purity. None of these purifications is mentioned in the Upanis. ads; they are found, however, in the Tantric literature dealing with Haṭha Yoga. Originating in the Tantric text Aghamarṣana, four methods of internal purification have evolved over time: the fivefold method of Bhairavi, the sixfold and eightfold methods of Śiva (aṣṭa karman), and the sixfold method of Gheranda.

These purifications deal on the one hand with the deep internal impurities of the organism, which require the application of Bhūta Śuddhi*11 and prāṇāyāma; they also concern the cleanliness of the tissues and organs of elimination, respectively.

To practice these various methods of internal cleansing, yogic students need first to follow the guru’s directions and indispensable supervision. However, to truly master these techniques, they must also mobilize their own faculties, their determination and will, and apply them to the control of the mind and muscles. A minimum of external means, such as the simple tongue scraper, will be enough, and air and water will achieve, for instance, the objective of nasopharyngeal cleaning.

Many criteria nourish the yogic ideal of purity. Yogis and yoginis do not conceive of their spiritual life only in terms of overall well-being, though this is an honorable ambition in itself. They know that beyond this they must have self-mastery in all the other phases of life. Yogis and yoginis are in fact comparable to warriors who have to fight on multiple fronts.

Included among their many objectives, with a concern for self-control underlying all, are enduring vitality, reduction of food wastes in the organism, body symmetry, and beauty and grace; in addition, they nurture the ambition of a clean and fragrant body, and effectiveness in action and thought. They seek energy and strength, endurance and serenity, and also the feeling of emotional fulfillment.

Of the four principal methods of internal purification, we will consider that of the yogi Gheranda, the most complete version. As its name indicates, ṣaṭ karman includes six acts:

- Dhautī: cleansing, using air and water, of the digestive tract, stomach, oral cavity, and ears

- Vasti: intestinal cleansing with air and water, which includes in particular Vāri Sāra and its easier variant Śaṇkprakṣalana

- Neti (Nasal Cleansing): cleans the nasal cavities and upper section of the throat using water and cotton yarn

- Naulī or Laulikī (Straight Muscle Exercise): fast gyratory movements of the rectus abdominis

- Trātaka (Gazing): exercise involving visually focusing on an object to the point of shedding tears

- Kapālabhātī: various nasopharyngeal techniques; in accordance with the method of Śivaism, the exercise of Kapālabhātī consists, in the practical teaching of Sri S. S. Goswami, of vigorous diaphragmatic hyperventilation

Neti is an easy form of cleaning renowned for preventing colds and stimulating the nervous system of the eye. Yogis usually rely on no mechanical aid, neti pot or the like, when practicing this exercise, which consists of sucking up one glass of lukewarm, salty water through the nostrils and immediately throwing it out through the mouth. In the next phase, cold water is retained in the mouth and immediately rejected through the nostrils.

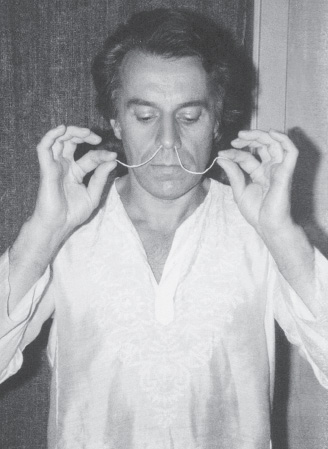

Sūtra Neti (Nasal Thread-Cleansing) consists of introducing a thoroughly boiled cotton thread into one nostril and expelling it via the mouth, then repeating with the other nostril. In the next and final phase, the thread is passed from one nostril into the other, as shown in the figure below, first in one direction, then the other.

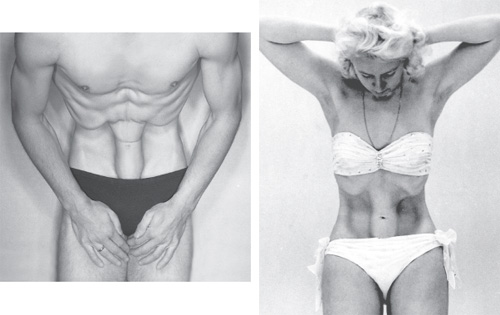

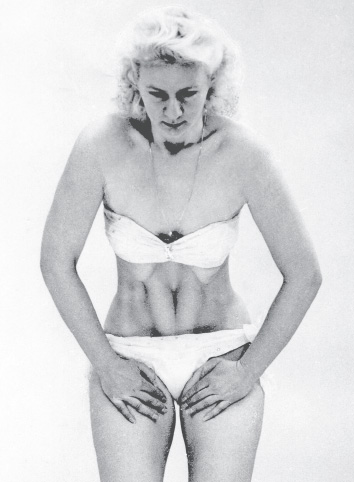

The multiform control of the rectus abdominis and its two adjacent semilunar lines, which is practiced in Naulī or Laulikī (Straight Muscle Exercise) is a typical yogic discovery. Besides developing the mental power to control—mostly by way of visualization, given that the exercise requires no significant muscular effort—the isolation of the central abdominal muscle illustrates clearly the pragmatic concerns to be found in the philosophy of Haṭha Yoga. The original yogic purpose of Naulī is to provide a natural means for auto-lavage (with no mechanical aid), which is possible when the anal muscles are fully relaxed.

Fig. 9.2. Naulī or Laulikī (Straight Muscle Exercise), control of the rectus abdominis

Only after having regularly practiced the six purifications will the yogi be able to begin the practice of prāṇāyāma (described in the next chapter), which is designed to eradicate deep internal impurities. Briefly let us note the method of Nāḍī Suddhi, an important component of the higher stages of the practice of prāṇāyāma. Nāḍī Śuddhi consists of removing any obstacle in the subtle intermediate sphere between the body and mind (nāḍī cakra), with the correct operation of the kinetic forces (vāyu) of prāṇa—in particular two principal forces, one solar, idā, the other lunar, pingalā, as well as the stabilizing force, suṣumnā, which balances them in perfect harmony.

Fig. 9.3. Separate isolation of the abdominal recti

Fig. 9.4. Advanced abdominal control unveiling the lineae semilunares

Advanced Exercises of Control

The advanced exercises of control involve the following procedures:

Vamana Dhautī (Gastric Auto-Lavage): In this process of self-cleansing of the stomach, the pupil drinks water and then vomits it, naturally, without external assistance. This method allows the washing of the stomach and reinforces the muscles involved.

Jala Vasti (Colonic Auto-Lavage): In this process of self-cleansing of the large intestine, the pupil draws up water through the rectum without mechanical assistance in order to clean the colon.

Śuṣka Vasti (Colonic Auto-Air Bath): This is atmospheric self- cleansing, in which the student draws in air through the rectum without mechanical assistance. The procedure is also used in prāṇāyāma.

Vāri Sāra (Alimentary Canal Auto-Lavage): In this process of self-cleansing of the digestive tract, the student drinks water, makes it pass from the stomach to the small intestine, then through the large intestine, finally expelling it via the anus, thus discharging all the fecal contents with it. This method is particularly effective for cleansing, without external assistance, the entire digestive tract.

Śankprakṣalana (Auto-Lavage of the Alimentary Canal): As effective but easier to perform than Vāri Sāra, this variation of self-cleansing of the digestive tract is carried out by drinking water in alternation with four movements.

Vāta Sāra (Alimentary Canal Auto-Air Bath): In this atmospheric self-cleansing of the digestive tract, the pupil swallows air, makes it pass from the stomach to the small intestine, then to the large intestine, finally ejecting it via the anus without mechanical assistance. This procedure is mainly used in advanced prāṇāyāma.

Vajrolī Mudrā: This is the most difficult of control achievements in Haṭha Yoga (see chapters 7 and 8 for details relating to this practice).