10

Prāṇāyāma—Respiratory Control

Haṭha Yoga teaches us that, in addition to the maintenance of a posture (āsana) in perfect immobility, the other condition required to reach deep mental concentration is the control of breathing (prāṇāyāma).

Prāṇa

The study of the fourth part of Haṭha Yoga supposes a high level of interest, as much for the practitioner as for the reader who is curious about the nature of prāṇa or the practice of prāṇāyāma. The term prāṇa signifies an idea with no equivalent in the Western world. It refers to the original principle of an energetic power inherent in any cosmic manifestation—a holistic, immanent energy that creates life itself, matter, and the world of the mind. In the following account, prāṇa will be presented only as this vital principle that underlies human life, a kinetic principle that the yogi uses in an important stage of spiritual research. To facilitate comprehension of the term, it can be simply translated as “vital force.”

Certain authors, probably inspired by the New Age movement, have wanted to make connections between mysticism (to which Yoga is often related) and research on the part of the scientific community, in particular in physics. However, the thesis of a primordial principle of universal energy does not feature among the concerns of the scientific community, whose spheres of interest are at the level of what is tangible, measurable, quantifiable, rational, and utilitarian. Though it is relatively easy to measure the pranic force expressed at the respiratory level, along with physiological and neurological modifications, it is more difficult to apprehend the nature of the operation of this pervasive primordial power, prāṇa. It is no less difficult to describe in rational terms the higher state of consciousnesses reached by yogis in samyama, which results specifically from the control of this same prāṇa.

The scientific validity of the Hindu conception of prāṇa cannot be found in any research results from the physical sciences nor in explanations coming from science in general, whose truths fluctuate according to whatever doctrine is in fashion. Obviously, scientific theories are subject to the passage of time, contrary to their object of study, which generally remains unchanged. In the Hindu conception, the physical sphere is at the lowest level of an extremely complex scale. Evolution here is the result of a timeless projection of the Supreme Consciousness, which itself generates a causality that, in turn, gives rise to an omnipresent subtle vital sphere, prāṇa. In a person, prāṇa vāyu is the bridge reaching toward the mind, which is nothing less than the dominant part of our being. prāṇa takes form and substance in a materiality where the individual, like a timeless Diogenes, uses the weak lantern of intellect and intuition to seek a Truth that is forever out of reach.

prāṇa is the global power that becomes altered when in contact with puruṇa, the basic principle of consciousness and prakṛiti (φ ση or nature), the potential of the cosmos and all the phenomena, including the mind. The developments and multiple manifestations of

prāṇa give access to an intermediate world, the vital world (nāḍī cakra), which is the constantly active sphere connecting the physical and mental realms, or, in conventional language, the body and soul.

ση or nature), the potential of the cosmos and all the phenomena, including the mind. The developments and multiple manifestations of

prāṇa give access to an intermediate world, the vital world (nāḍī cakra), which is the constantly active sphere connecting the physical and mental realms, or, in conventional language, the body and soul.

While prāṇa infuses life into all organic matter, prāṇāyāma allows the return to the latent state of prāṇa. In a pranic state, which is by nature supramental, the body is inanimate but enlightened by a massive interior consciousness (ghana prajña). From the yogic point of view, this state contradicts the scientific epistemological assumption according to which the mind is ultimately only a product of complex cerebral activities.

Nāḍīs and Vāyus

The sacred writings of the Vedas and of Tantric literature mention the sphere of nāḍīs, the nāḍī cakra. Derived from the Sanskrit word nāda, this term indicates “that which radiates,” “the kinetic,” or “that which has to do with movement.” Whether physical or subtle (in which case the term yogannāḍī is used), the Tantras teach that the nāḍīs are innumerable. In Yoga, this aspect allows the reconnection of the subtle world to the sensory world.

The subtle body of a person is composed of three principal nāḍīs. The first, idā, appears in lunar form (candra) and the second, pingalā, symbolizes the sun (sūrya). These two subtle currents assume the passage of the vital current, which passes through the nostrils from atmospheric air. Usually inactive, the third, suṣumnā, plays an important role in the passage of Kuṇḍalinī (the Grand Spiritual Potential of Consciousness) through the different cakras (energy centers). Inseparable from the nāḍīs are the vāyus (also called prāṇa vāyus), the kinetic manifestation of the pranic force. Of the ten vāyus, five assume an essential role in the expression of prāṇa’s state of perpetual motion: prāṇa, apāna, samāna, udāna, and vyāna. To summarize Sri S. S. Goswami’s technical interpretation of these subtle elements, the nāḍīs are the pranic expression of radiating lines, inseparable from the movements (vāyus) of prāṇa.

Strictly from the point of view of Haṭha Yoga, breathing is much more than the expression of our vitality or the movement of the organs, which are our lungs, heart, and all the muscles involved in the vital processes. For the yogi, breathing is the physiological expression of a vital kinetic current (prāṇa vāyu), an aerobic manifestation closely related to the mental life, which primarily expresses an orientation that is characteristic of awareness of the outside, together with a spontaneous inward movement.

Practice of the Discipline

While prāṇa is effectively mentioned in the Vedic literature, the word prāṇāyāma, on the other hand, does not appear there. Patañjali introduced the Brāhmaṇic term into the discipline of Haṭha Yoga. According to his Yoga Sūtras, the practice of prāṇāyāma allows the elimination of that which obstructs the light of the vital body (II.52) and prepares the adept for mental concentration (II.53). Practitioners of prāṇāyāma have long observed the interaction of the mind and breathing and been aware of the influence of this natural phenomenon on the flow of the mind. In this way, they have shown its positive effects on the immune system, physical development, and the strength of the whole organism.

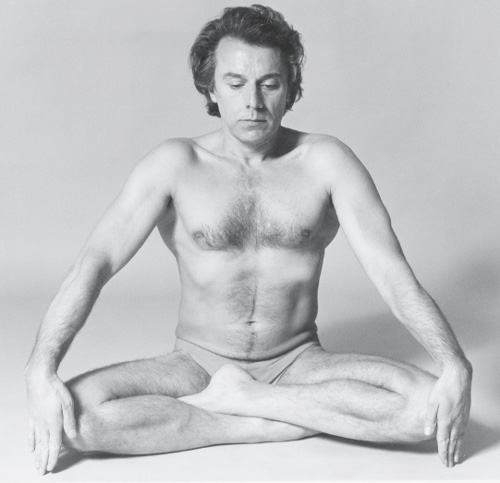

The discipline of prāṇāyāma is divided into two principal categories: respiratory control (or mastery of the breath) and concentration. In Haṭha Yoga, prāṇāyāma is done in association with dynamic āsanas and cāraṇā. The practice of voluntary breath control is usually done in crossed-leg sitting posture. To be efficient, the practice should be undertaken with an empty stomach and a quiet, well-controlled mind. The surroundings should be silent and clean. If the practice is just for the purpose of wellness, it should be done outdoors.

The exercises of voluntary breathing are broken down into three phases: hyperventilation, hypoventilation, and retention or suspension of the breath (or apnea). Voluntary hyperventilation is divided into two forms: it can be diaphragmatic (Kapālabhātī) or thoracic (Bhastrikā). Practiced regularly in the teaching of the Goswami Yoga Institute, these respiratory exercises in particular have permitted the reconsideration of maximal hyperventilation previously expressed in handbooks on the physiology of the human lung. Until quite recently it was thought that voluntary hyperventilation could not exceed 100 breaths per minute. However, the pupils of the Goswami Institute have reached voluntary frequencies of hyperventilation much higher than this limit. The hyperventilation of prāṇāyāma allows one to go from 60 to 120 breaths per minute, finally attaining a standard of 240 breaths. Certain established students of Sri Goswami exhibited periods of hyperventilation exceeding 300 breaths per minute! Another teaching, drawn from the practice of Kapālabhātī and Bhastrikā, is the fact that regular and prolonged exercise makes it possible to avoid the risk of acidosis, even when yogic hyperventilation is maintained without interruption during an hour or more.*12

Fig. 10.1. Prāṇāyāma generally starts with a prolonged period of either abdominal (Kapālabhātī) or thoracic (Bhastrikā) hyperventilation, soon followed by long-slow breathing exercises, with or without breath suspension. Advanced breath control leads to automatic apnea and modified consciousness. In exceptional cases, it may induce body levitation.

The individual’s natural phases of breathing are methodically modulated by the prolongation, reduction, or cessation of inhalation or exhalation. The terms for these three components of the respiratory exercises—pūraka (controlled inhalation), recaka (controlled exhalation), and kumbhaka (controlled retention or suspension)—appear in the Upaniṣads, Tantras, and Purāṇas, as well as in modern yogic terminology.

Of these three phases of respiratory control, the retention of the breath is regarded as most important because it particularly promotes the faculty of concentration. However, when a man or woman suffers from psychosomatic imbalance, the mind is functioning on a more subtle level than that of the body. It is then impossible to prolong the retention of the breath in a truly beneficial way for the practice of mental concentration. To try and retain the breath by a physical effort at this point scarcely makes sense, except for the development of willpower.

The control of the breath is done in stages. Only the accomplished practitioner in the discipline of prāṇāyāma will be able to progress toward perfection, while at the same time not neglecting the body. It is possible to affect the level of mental tranquility and physical immobility by determining the frequency and depth of breathing. The maintenance of a motionless and stable body for a long period makes it possible to considerably decrease the frequency as well as the amplitude of breathing. Gradually, this exercise becomes easy for the practitioner insofar as the mind becomes increasingly calm and concentration deeper. At a certain level of development, the practitioner’s breathing will become barely perceptible: breathing of the hamsa type, which precedes the total and spontaneous suspension of the breath (kevala kumbhaka). It is also one of the yogi’s aims to awaken the Kuṇḍalinī using prāṇāyāma.

From the above, it emerges that the state that best suits mental concentration is in direct opposition to any state that favors movement. In addition, let us underline that beyond the goals and specific results of prāṇāyāma, the practice of this discipline produces effects of well-being that are far from negligible. They seem to us worthy of mention.

First of all, the regular practice of prāṇāyāma helps the practitioner to reinforce and gain greater mastery of all the physical elements involved: muscles, lungs, heart, arteries, and nervous system. Energy is increased and ventilation improved.

Moreover, it permits awareness of the benefits arising from complete breathing, such as a better control of the senses and increased tone of the organs—in particular, peristalsis, those wave-like alternate contraction and relaxation movements in the alimentary canal that progressively push forward its contents.

Combined with other exercises like āsanas, purifications, and a suitable diet, the regular practice of prāṇāyāma promotes good health and physical performance.

Another advantage of a regular practice of prāṇāyāma is to make it possible for the individual to experience privileged moments, sublime impulses, elevation of the soul, strokes of genius, or waves of spiritual immersion. However, to be complete, the practice of higher prāṇāyāma supposes sexual control, or brahmacarya, lest the practitioner’s health is put at risk.

In short, the discipline of prāṇāyāma makes the yogi virtuous—in the etymological sense of the Latin term virtus, a valorous person who is aware of his or her strength.

The historical evolution of this technique saw the development of many versions of the ancient discipline of prāṇāyāma. On a higher level, the advanced yogi, subjected to a strict milk diet, will practice the control of prāṇa over periods ranging from nine to twelve hours per day. It is at the end of the final phase of Sahita Prāṇāyāma, characterized by the spontaneous cessation of breathing (kevala kumbhaka), that the rare antigravitational phenomenon of levitation occurs.

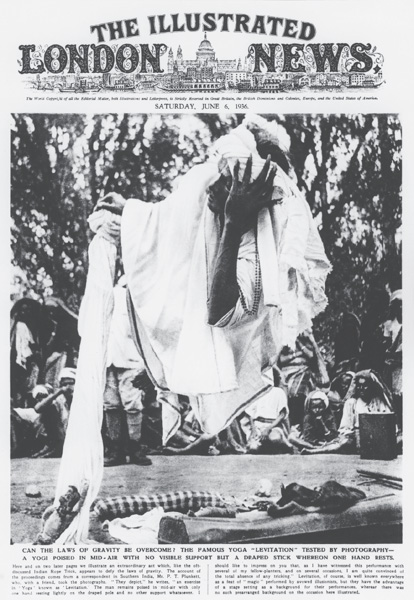

When it published the picture shown in fig. 10.2 The Illustrated London News reported:

The levitation lasted for about 10 minutes including 5 minutes for the yogi to come down from the top position to the ground. On one shot at the initial stage, the yogi’s face appears to be quite normal. However, during the raising of the body clear signs of fatigue appear, the turban falls down, the hand on the stick appears more contracted and the countenance shows signs of inner tension culminating in an expression of exhaustion when reaching the ground. By passing a stick above, underneath and around the yogi’s body, the British observer of this feat of superhuman powers checked that the performance was actually no fake, and ensured that there was no other support than the stick on which the yogi’s hand was resting.

Nāḍī Śuddhi

The purification of the body is closely related to Nāḍī Śuddhi, an important subdiscipline of Haṭha Yoga. With this method, the body is completely purified and the slowest of its vibrations is modified, so that they are able to mix with the subtlest mental vibrations. From the point of view of the mind, it becomes calmer, more focused, and joyful, with subtler vibrations and elevated thoughts. Purified, the body no longer has a cumbersome influence on the mind. Through Nāḍī Śuddhi the body is cleaned, revitalized, and rebalanced. It becomes healthier and lighter, and it releases a pleasant fragrance.

Nāḍī Śuddhi includes Samanu (which, in prāṇāyāma, is referred to as Nāḍī Śuddhi prāṇāyāma) and Nirmanu or acts of body purification, commonly called ṣaṭ karman (six acts). The method known as Nāḍī Śuddhi Prān. āyāma consists of a process of internal muscular contraction intended to allow prolongation of the apnea. This contraction is caused by Jālandhara Bandha (Chin Lock), Uḍḍīyāna Bandha (Abdominal Retraction), and Mūla Bandha (Anal Lock). The method insists on these three simultaneous contractions being performed maximally. To reinforce the first contraction, two special exercises are envisaged: Meru Cālana (Throat Exercise) and Mani Cālana (Trunk and Throat Exercise). It should be also noted that the pressure exerted on the abdominal cavity during Uḍḍīyāna and Mūla Bandha will not give the required effect if the intestine is not perfectly clean. This is the very raison d’être of the different purifying exercises prescribed by yogis, detailed in the previous chapter, “Ṣaṭ Karman—Purifications.”

The advanced technique of Khecarī Mudrā makes it possible to obtain an internal pressure capable of facilitating the retention of breath. Rare are the practitioners who will use this difficult exercise, which requires intense training under the supervision of a qualified teacher. The method, which supposes many preliminary manipulations, consists of an introversion of the tongue that, folded up on itself, must penetrate toward the back of the oral cavity until it covers the glottis. The point of the folded tongue blocks the respiratory tracts and creates a degree of internal pressure. Jālandhara Bandha and Mūla Bandha are parts of the practice of Khecarī. Practiced in an inverted posture, this method is then called Viparītakaraṇī Mudrā.

Svara Yoga

Svara Yoga, a little known variation of prāṇāyāma, is an ancient, special discipline based primarily on the principles of prānāyāmic control of the prāṇa and nāḍīs, the kinetic lines of the vital force. The pragmatism of Svara Yoga is expressed in the control over the relation that exists between breath and psyche. It has been adopted by certain yogis for whom life is not measured in terms of days and years, but by the rhythm of their own breathing. The intensity of the passage of air through our nostrils varies during normal breathing. The air goes through our nostrils in an alternating process, according to an infradian biological cycle (a period longer than twenty-four hours) that differs appreciably from the circadian one, which is to say it is considerably less than a day. In India, nasal respiratory alternation is an age-old recognized physiological phenomenon.

The practitioner of Svara Yoga excels in the knowledge of the complex phenomenon of prāṇa and of the nāḍīs. Thanks to the study, observations, and experiments of yogic predecessors who have investigated the respiratory cycle, practitioners can in turn discover the subtle changes that occur in their organism, in particular the correlation that exists between breathing and the mind. They will also learn, with the assistance of appropriate techniques, how to modify the alternation of their breathing at will and at their own pace.

When the breath is more pronounced on the right side, it is the influence of pingalā, a “solar” energetic principle, which is represented symbolically by the god-awareness Śiva. More marked breathing on the left side is “lunar,” which is a tendency of the idā nāḍī, represented by the power of Śakti. The first predominance denotes dynamism and extraversion, while the second expresses its opposite, introspection and quietude.

This empirical knowledge symbolically reveals the characteristic inherent dualism*13 of the human condition. By subtly observing their breath, yogis can determine their choice of action in the immediate future and the perfect moment for each one of their actions, such as meals, rest, travel, in short all the activities of life, sacred or social.

It is at the heart of this practice, beyond the contingencies of a life of constraints, that the yogi will endeavor to equalize the pranic idā and pingalā currents into a perfect balance, in the third main nāḍī— suṣumnā. It is precisely this union of binary energies, which corresponds to the fusion of the forces ha and ṭha, that is peculiar to the discipline of Haṭha Yoga. The retraction of the mind from the object of the senses, pratyāhāra, which precedes profound mental concentration, occurs at the end of prāṇāyāma.