Introduction ix

1 Value 1

2 Corporate finance 49

3 Accounting 97

4 Managing value 117

5 The nature of financial markets 153

6 Equity markets in action 175

7 Debt markets 217

8 Portfolio investment 259

9 Risk management 289

10 Derivatives 331

11 Financial institutions 361

12 Regulation and governance 395

13 Finance and government 419

Glossary 439

Subject index 451

Name index 461

Organization index 464

The Financial Times Mastering Series has been the product of a unique collaboration between the FT and some of the world’s leading international business schools. This is the third book to emerge from that partnership and like its predecessors Mastering Management and Mastering Enterprise (also FT Pitman Publishing) we believe it combines essential theory with both relevant and recent practice.

The book - a revised version of articles published in weekly instalments in the European editions of the Financial Times newspaper during the summer of 1997 - brings together more than 60 articles from contributing faculties at the Chicago Graduate School of Business, London Business School and the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. This is a writing team which is virtually unbeatable in the field of finance and the result is a valuable compendium suitable for students and practitioners alike.

The book is structured into 13 modules: Value; Corporate finance; Accounting; Managing value; The nature of financial markets; Equity markets in action; Debt markets; Portfolio investment; Risk management; Derivatives; Financial institutions; Regulation and governance; and Finance and government.

Brief introductions to each module explain the significance of the different topics and the summaries at the end of each article are designed to help readers quickly identify subjects of special

interest. Lists of further reading ideas will be helpful for those who want to delve deeper.

Mastering Finance is not a beginner’s guide - many other books serve that purpose - and it therefore assumes a basic knowledge of such concepts as cash flow, working capital and dividend yield. The finance module of Mastering Management may be the best starting point for those in need of a basic grounding.

As with the other FT Mastering books there have been many people who made this project possible and without whom the challenge of bringing together such a diverse and distinguished group of contributors could not have been met. Inevitably, however, the burden fell most heavily on the academic and administrative co-ordinators at each school, namely Emeritus Professor Harold Rose (LBS), Professor Richard Leftwich and Allan Friedman (Chicago) and Professor Michael Gibbon and Michael Baltes (Wharton). For their tireless work and support we are extremely grateful.

Finally, if you have enjoyed this book you will be glad to know that there are more Mastering books on the way: the next two topics in the FT Mastering Series will be Mastering Global Business and Mastering Marketing.

Tim Dickson and George Bickerstaffe November 1997

’

Contributors

Jeremy J. Siegel is Professor of Finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. In addition, he is Academic Director of the US Securities Industry Institute and a member of the advisory board for the Asian Securities Industry Association.

Massoud Mussavian is Assistant Professor of Finance at London Business School. His research interests include continuous time finance, investment and fund management compensation.

Robert Z. Aliber is Professor of International Economics and Finance at the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business. He is director of the School’s Center for International Finance.

Donald B. Keim is Professor of Finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Elroy Dimson is Professor of Finance at London Business School. With Paul Marsh he is editor of LBS’s Risk Measurement Service.

Gabriel Hawawini is the Henry Grunfeld Professor of Investment Banking at INSEAD and the author of several books and research papers on various aspects of the financial services industry.

Howard Kaufold is an adjunct Professor of Finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and Director of the Wharton Executive MBA Program.

Luigi Zingales is Associate Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business. His research interests include capital structure and corporate control.

Isik Inselbag is an adjunct Professor of Finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and former Vice Dean and Director of the Wharton Graduate Division.

1 • Value

Contents

Risk and return: start with the building blocks 5

Jeremy Siegel, The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania A look at the relevant historical data for assessing future performance of stocks and bonds.

Capital budgeting: will the project pay? 12 Robert Aliber, University of Chicago Graduate School of Business

Valuing projects in foreign markets and discussion of the capital budgeting algorithm.

Capital budgeting: a beta way to do it 17 Elroy Dimson, London Business School A look at one popular task for assessing risk and return: the Capital Asset Pricing Model.

Valuation approaches to the LBO 24 Isik Inselbag and Howard Kaufold, The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania A look at the methods used to determine the value of a leveraged buy-out (LBO).

An APT alternative to assessing risk 31 Massoud Mussavian, London Business School A look at another way of assessing risk - the arbitrage pricing theory.

Beta, size and price/book: three risk measures or one? 36 Gabriel Hawawini, INSEAD

Donald Keim, The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

Discussion of many different patterns in stock returns - company size, ratio of bank-to-market value and prior return performance.

Why it’s worth being in control 43 Luigi Zingales, University of Chicago Graduate School of Business

The private benefits of being a controlling shareholder.

Introduction

Valuation lies at the heart of all stock market and business investment. This module introduces the concept of risk and return, examines different methods of capital budgeting (including the famous Capital Asset Pricing Model), offers advice on valuation to anyone contemplating a leveraged buy-out, and considers the benefits of being a controlling shareholder.

by Jeremy J. Siegel

O nce risk and return are specified for a given asset or asset class, modern financial theory can identify the best portfolio allocations subject to the risk tolerance of the investor. Yet expected returns are not physical constants, like the speed of light, waiting to be discovered in the natural world. They must be deduced from historical data, tempered with an appreciation of how current economic, social and political factors may modify the parameters derived from the past.

There is certainly no lack of data in the field of finance. The breadth and scope of quantitative information available is unrivaled in the field of social science. Nevertheless, there is still widespread disagreement among professionals about the best estimates of the risk and return on the two largest classes of financial assets: stocks and bonds.

The plethora of data does not necessarily guarantee precision in estimating expected return because one can never be certain the underlying factors that generate asset prices will remain unchanged. As Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson is fond of saying: we have but one sample of history.

Historical estimates

Let us begin with the US and the UK shortly after the First World War. The virtue of this period is that it covers the major stock market cycle: the spectacular rise in stock prices in the late 1920s and the devastating decline which followed, as well as the Second World War and the great post-war expansion. However, using this period as a benchmark for estimating future returns has its drawbacks. In contrast to the 1930s, the greatest threat to economies today is from inflation, not deflation.

The reasons for the shift to an inflation-prone rather than deflation-threatened economy are well understood. The gold-based monetary standard, which had ruled in the industrialized world for more than two centuries, was abandoned in the 1930s following the Great Depression. Governments shifted to a paper-based standard, which is now universal in both developed and developing countries.

This shift dramatically changed the dynamics of the price level, leading to a decided bias towards inflation. In fact, in both the US and the UK, the whole of the accumulated rise in the prices of goods and services that has taken place in the past two centuries has occurred since the Second World War. From 1800 through 1945 the overall level of prices, although subject to substantial short-run volatility, was basically flat. The change in the monetary standard from gold to paper had its greatest effect on the returns to fixed income assets. It is clear in retrospect that the buyers of bonds in the 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s did not recognize the consequences of the change. How else can one explain why investors voluntarily purchased long-term bonds with three per cent and four per cent coupons despite the fact that government policy was geared to avoid deflation? Data from the post-war years will most certainly exhibit depressed returns on long bonds.

But what effect does the shift in the monetary standard have for the return on equities? In theory, stocks are claims on real assets: capital and land, which derive their value from the sale of real goods and services. Theory suggests that, at least in the long run, stock returns should not be influenced by fluctuations in the monetary standard. Yet in the short run equities have proved extremely poor hedges against inflation, as the 1970s dramatically demonstrated. Whether long-term equity returns are influenced by inflation can only be answered by comparing the returns of the past 50 years with those which came earlier.

Building on the work of Alfred Cowles and William Schwert, I derived the before and after-inflation returns on stocks and bonds in the US going back to the beginning of the 19th century. Figure 1 displays the growth in the total real returns from 1802 through 1996 (including capital gains, interest and dividends) on stocks, bonds, bills, gold and the value of the US dollar.

This two-century history is divided into three sub-periods. The first, from 1802 to 1871, represents the early stage of US economic development. During the second period, from 1871 to 1925, the US was transformed into one of the great industrial powers of the world. The third sub-period, from 1926 to the present, marks the mature phase of financial markets and has become the most popular benchmark for analyzing historical returns.

The growth of the purchasing power of a diversified equity portfolio not only dominates all other assets but is remarkable for the stability of its long-term after-inflation returns. Despite extraordinary changes in the economic, social and political environment over the past two centuries, US stocks have yielded between 6.5-7 per cent per year adjusted for inflation in all major sub-periods.

Fig.1 US stocks and bonds - a long view

till®

Total real return index, semi-log scale

$ 1 , 000,000

Stocks

$100,000

$ 10,000

$1,000

$100

$10

$1

$0.1

Dollar

1800

1900

80 90

Table captionReal returns (%)

1802- | 1802- | |

1996 | 1871 | |

Stocks | 6.9 | 7.0 |

Bonds | 3.4 | 4.8 |

Bills | 2.9 | 5.1 |

Gold | 0.1 | 0.2 |

Dollar | -1.3 | -0.1 |

Gold

Bonds

Bills

1871- | 1926- |

1925 | 1996 |

6.6 | 6.9 |

3.7 | 1.9 |

3.2 | 0.6 |

-0.8 | 0.6 |

-0.6 | -3.0 |

Real dollar stock return indices, semi-log scale 100

10

Germany •'

US Germany UK Japan

6.9% 7.1% 6.3% 4.8%

. Japan

0.1

1925 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95

The consistency of the real return on equities is striking given the shift from a predominantly agricultural economy of the early 19th century to an industrialized economy and finally to a service and information-oriented, post-industrial economy as we head towards the next millennium. The long-term stability of the real return on equity also persisted whether the monetary system was based on gold or paper. Some economists have cast doubt on the use of US and even UK data to predict the future. They note that these countries have emerged victorious in all major wars and survived all the significant crises. They claim it is a grave mistake to take these countries as typical of equities worldwide.

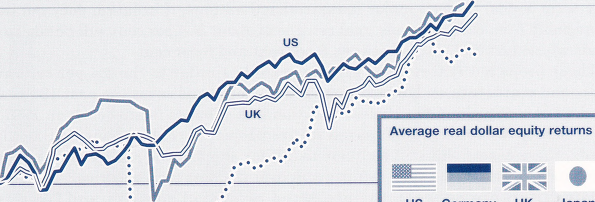

Yet my examination of equity returns in foreign countries confirms, rather than casts doubt on the superior performance of equities. Figure 2 shows the real dollar returns on stocks in the US, the UK, Japan and Germany from 1926 to the present. Special attention is given to computing the returns on equities throughout the Second World War in order to maintain a continuous series.

The devastating defeat of the Axis powers did cause German and Japanese stocks to fall dramatically. But their recovery has been equally spectacular. The compound annual real dollar returns on stocks in the UK, Germany and the US fell within one percentage point of each other. Although real dollar Japanese equity returns lagged at 4.8 per cent a year, they easily exceeded the returns on fixed income assets in any country during this period. The ability of stocks in the developed nations to recover from wars, hyperinflations and depressions is remarkable and demonstrates that the superior long-term returns on equity are a worldwide phenomenon.

In contrast to the remarkable stability of real stock returns, real returns on fixed- income assets have declined markedly. In the first, and even second, sub-periods the returns on bonds and bills, although less than equities, were significantly positive. But since 1926, and especially since the Second World War, fixed income assets have returned little after inflation.

Whatever the reasons for the decline in the return on fixed income assets over the past century, it is almost certain that the real returns on bonds will be higher in the future than they have been in the past 70 years. As a result of the inflation shock of the 1970s, bondholders have incorporated a significant inflation premium in the coupon on long-term bonds. In most major industrialized nations, if inflation does not increase appreciably from current levels, real returns of about 3—4 per cent will be realized from bonds whose nominal rate is between 6 per cent and 8 per cent.

These projected real returns are remarkably similar to the 3.4 per cent average compound real return on US long-term government bonds over the past 194 years and the 3.4 per cent yield of the 10-year inflation-linked bonds floated early in 1997 by the US treasury. Despite the increased future projected real returns on fixed income assets, these assets will still be likely to fall far short of the real returns on equities, which have averaged between 6—7 per cent over the past two centuries.

The difference between the projected return on equities and fixed income investments is called the equity premium. Few question the fact that the return on stocks is likely to dominate that on bonds over the long run. The question is whether the risks inherent in stocks are sufficient to explain the three to four percentage point difference in their projected returns.

The risks and valuation Explaining the equity premium

The difference between stock and bonds returns has traditionally been explained by the greater risk inherent in equity investments. This risk has been measured in several ways.

In the standard version of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), the risk premium on an asset depends not on the standard deviation of its own return but on the correlation of its return with the ‘market portfolio,’ which comprises stocks, bonds, real estate and perhaps even human capital.

More recent formulations of CAPM replaced the market portfolio, which is always difficult to measure, with the variable that most directly affects an investor’s welfare, the level of consumption’. In this model, an investor’s taste for taking risks in the market are critically linked to whether poor stock returns are correlated with other bad economic outcomes, such as economic recessions. But this approach (called the ‘consumption CAPM’) yielded bothersome results. Empirical tests revealed that the correlation of stock market returns with aggregate economic activity was very low. Therefore investors should not be very averse to taking risks in stocks, since a plunging stock market does not usually mean other forms of economic wealth are also sinking.

In order to explain the excess return of stocks over bonds in these models, one would have to postulate an extremely high level of risk aversion, a level which many regarded as an unrealistic description of individual behavior towards risk. But the difficulty of explaining the magnitude of the equity premium is not limited to the capital asset pricing model. The usual measure of risk that forms the basis of modern portfolio analysis is the standard deviation of one-year returns. Yet one can ask whether this measure is appropriate for an investor’s portfolio whose holding period extends much longer than one year.

In the past, researchers have said the holding period does not matter. It can be proved mathematically that if returns follow random walks, that is, future returns are

Fig.3 How risk reduces if you hold 01

Standard deviation of average annual real returns, 1802-1996

20%

Source: Jeremy J. Siegel

Holding Period (years)

in no way dependent on past returns, then the period over which risk and return are measured is irrelevant. Specifically, both total risk and total return increase linearly in the time period, so the relative risks between assets remain unchanged and the length of the period chosen to measure risk is of no consequence.

But if asset returns do not follow a random walk, then the period chosen to measure risk matters substantially. The examination of longer-term return data show important deviations from random walk behavior. Figure 3 plots the standard deviation of average annual real returns over one, two, five, 10, 20 and 30 year periods for stocks, bonds and bills. Risk, defined as the standard deviation of average annual returns, declines almost twice as fast as the holding period increases for stocks compared with that predicted by the random walk theory (the Theoretical risk’). There is clear evidence of mean reversion of real stock returns.

In sharp contrast to stocks, the standard deviation of the average annual real returns on fixed income assets declines more slowly than theory would predict as the holding period increases. This is called mean aversion, which describes the behavior of a variable that tends to wander from its mean value, rather than be drawn to it, as is the case for equities. Fixed income assets display mean aversion because their real return is critically influenced by inflation - and inflation cumulates over time.

The cumulative effects of inflation can be readily seen in Figure 4, which displays the total real return in stocks and fixed income assets of the US and the UK and fixed income assets in Germany, and Japan. It is not surprising that the worst bond returns come during periods of the most rapid inflation: the 1970s for the US and UK; the postwar period for Japan; and the German hyperinflation of the early 1920s.

Finance theory is thus presented with a conundrum. Stocks are riskier than bonds in the short-run but are actually less risky in the long-run. The optimal allocation of one’s portfolio cannot be divorced from the holding period of the investor. Given the choice between stocks and bonds, the evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of the former for the long-term investor.

Fig.4 Stocks vs bonds; the effects of i

WHi!

—■

International total real return indices, semi-log scale 10,000

US Stocks

Valuation yardsticks

Many yardsticks have been used to evaluate whether stock prices are overvalued or undervalued. These include price/earnings ratios, dividend yields, book-to-market ratios, and the total value of equity relative to some aggregate, such as gross domestic product or total replacement cost of the capital.

But since the returns on equity have been much larger than can be explained by economic models, the past is likely to be a poor indicator of the ‘right' value for stocks. In fact, the superior returns on stocks are strong evidence for the chronic undervaluation of equity prices relative to their fundamentals. The valuation factor that most closely matches the 6.5-7.0 per cent long-run real return on equity is the average earnings yield on stocks. The earnings yield is the ratio of earnings to the price of the stock or the reciprocal of the P-E ratio.

In the period from 1871 to 1997 the median earnings yield on stocks in the US market has been 7.3 per cent, just 0.4 per cent above real stock returns. The reasons why the earnings yield approximates the real, and not nominal, return to shareholders is that stock returns are based on the productivity of real assets whose value should, in the long run, change with the overall price level.

Some researchers have considered the dividend yield the most important indicator of stock value. But focusing on dividends ignores the other ways that companies can create value for the shareholder with earnings that are not paid out as dividends - retained earnings.

Retained earnings can be used to buy back shares, to retire debt or to reinvest for growth. These actions will increase future per share earnings. If the return which the organization receives from its retained earnings matches that which can be achieved by the individual investor, the dividend payout will not matter.

In equilibrium, the market value of assets should converge to the cost of producing these assets, otherwise there would be incentives to invest in capital and sell stock, if the market were higher, or buy stock and sell capital if the market were lower. This

Risk and return: start with the building blocks

ratio, called ‘Tobin’s Q,’ is named after the Nobel prize-winning economist James Tobin, who popularized the concept.

The problem with this measure is that there are many reasons for a large gap between the market value of capital, which depends on the earning power of the company, and the cost of replacing its physical capital. The value of a business goes far beyond the bricks and mortar used to build the plant and equipment. Such difficult-to- measure factors as intellectual property, managerial skill and the ability to configure the production process to satisfy consumer demands can overwhelm book value, even when adjusted for changing replacement costs.