T he Weiss Center for International Financial Research of the Wharton School undertook a survey of derivatives usage and practice by non-financial corporations in the US in November 1994. In late 1995, with the support of CIBC Wood Gundy, a more detailed survey was conducted, with a broader range of questions about valuation and risk measurement and with more specific questions about the use of derivatives. This article reports some of the findings of the second survey.

For the survey, derivatives are defined narrowly as forwards, futures, options and swaps plus broader contracts that contained one or more of these instruments in their structure. The primary objectives of this survey, as with the original 1994 survey, were to sample derivatives activity from a broad cross-section of US firms to better understand current practice as well as to develop a database on risk-management practices suitable for academic research.

The survey was sent to a sampling of more than 2,000 US businesses. A total of 350 companies responded: 176 from the manufacturing sector; 77 from the primary products sector, which includes agriculture, mining, energy and utilities; and 97 from the service sector.

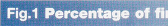

The first question asked whether companies use derivatives. Of the respondents, 142 (41 per cent) said they used derivatives. Figure 1 presents the responses broken down by company size and industry sector. Fifty nine per cent of large companies (market value greater than $250m) use derivatives. The percentage drops to 48 per cent for medium-sized businesses (between $50m and $250m market value) and to only 13 per cent for small organizations (less than $50m).

By industry, derivatives use is greatest among primary product producers, which is not surprising given that futures exchanges were originally established to help such companies manage their commodity risks. Not quite so many manufacturing companies use derivatives. The use of derivatives is smallest in the service sector. We found that notwithstanding several widely publicized financial debacles related to the improper use of derivatives, our sample results suggested that the number of businesses using derivatives increased in 1995 over 1994. The increase, however, was very small.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Percentage

The survey asked companies to indicate how they used particular types of derivatives instruments to manage exposure across four broad classes of financial price risk: foreign currency, interest rate, commodity and equity.

For each source of risk, we asked if they managed their exposure, and if so, to rank their usage of seven types of derivative instruments: forwards, futures, swaps, over- the-counter (OTC) options, exchange-traded options, structured derivatives (combinations of forwards, swaps and options) and hybrid debt (straight debt with embedded derivative instruments) in terms of importance to their company for managing that exposure.

Seventy six per cent of all derivatives users in our survey manage foreign exchange risk using foreign currency derivatives. Among the foreign currency derivatives the companies use, the forward contract is the most popular choice. More than 75 per cent of businesses rank the forward contract as one of their top three choices among foreign currency derivative instruments with more than 50 per cent ranking it as their first choice. OTC options are also a popular foreign currency derivative instrument, with about 50 per cent of the organizations choosing this as one of their top choices. Among the remaining instruments, swaps and futures are the most popular.

Among derivatives users in the survey, 73 per cent indicate they manage interest rate risk. Not surprisingly, the overwhelmingly popular choice among instruments in this area is the swap; 78 per cent of companies list swaps as their first choice among interest rate derivative instruments, with 95 per cent ranking it as one of their three top choices. Structured derivatives, OTC options and futures are the next most popular.

Commodity price risk is managed using derivatives by just 37 per cent of the derivatives users in our survey. Among instruments in this risk class, futures contracts

Hi I

fffff

By size and sector

Large

(<$250m)

Medium

($50m~$250m)

Small

(<$50m)

Primary

products

Manufacturing

Services

HttHfl

WSmKk

■H

msBi

§111111

To manage the cash flows of the firm To manage accounting earnings of the firm To manage the market value of the firm To manage the balance sheet accounts of the firms

49 per cent 42 per cent 8 per cent 1 per cent

are the most popular derivative; 42 per cent of all commodity derivatives users rank futures as their first choice, with an additional 23 per cent ranking them as a second or third choice. Swaps and forwards come in close behind futures in popularity, with more than 50 per cent of commodity derivatives users putting

these instruments among their top three choices. Both OTC options and exchange- traded options are listed as the first-choice instrument by eight per cent of users, although OTC options are far more popular as second or third choices.

Finally, equity risk is the risk class least likely to be managed with derivatives: just 12 per cent of all derivatives users in the sample indicate usage of equity derivatives. Among the instruments used in this class, OTC options are the most popular. They are the first choice of nearly 50 per cent of users.

Since the most common use of derivative instruments is for risk management, we wanted to identify what risk-management objectives companies were trying to achieve. We asked those that use derivatives for hedging to rank the importance of four different goals of their hedging strategies: managing volatility in accounting earnings; managing volatility in cash flows; managing balance sheet accounts or ratios; and managing the market value of the company.

The responses for the ‘most important’ are summarized in Table 1. Managing cash flows is the top choice, with 49 per cent of respondents indicating that this is the most important objective of their hedging strategy.

Managing the fluctuations in accounting earnings is a close second with 42 per cent of businesses indicating this is the ‘most important’ objective of their hedging strategy. While in many cases the impact of hedging on reported earnings and cash flows may be similar, the popularity of the former objective may suggest that some companies focus hedging strategy more on stabilizing the reported numbers presented to investors than stabilizing the actual internal cash flows.

A distant third among the objectives is managing the total market value of the company, which is the ‘most important’ objective of just eight per cent of the respondents. Since firm value is theoretically equal to the present value of expected future cash flows, the difference between the importance of this objective and the cash flow objective may be more a matter of the time frame of hedging than its intent. Finally, only one per cent of the companies indicated that they hedge to manage balance sheet ratios.

The use of derivatives in today’s market involves many issues. Respondents were asked to indicate their degree of concern about a series of issues regarding the use of derivatives. These include: credit risk, uncertainty about hedge accounting treatment, tax and legal issues, disclosure requirements, transaction costs, liquidity risk, lack of knowledge about derivatives within the organization, difficulty quantifying the business's underlying exposure, perceptions about derivatives use by outsiders, pricing and valuing derivatives, monitoring and evaluating hedge results and evaluating risks

of proposed derivative transactions. For each issue, businesses were asked to indicate a high, moderate, or low level of concern or indicate that the issue was not a concern.

Credit risk is the issue that most seriously concerns derivatives users. Thirty-three per cent express a high degree of concern, with an additional 35 per cent indicating a moderate degree of concern about credit risk. Whether this concern is due to systemic risk (wide-spread market collapse due to an initial set of defaults) or non-delivery on individual contracts is not clear. However, the issue of timely and complete payment of derivative transactions is of significant concern among derivatives users.

Perhaps in light of the large losses that occurred in well-known derivatives disasters in 1994, companies expressed considerable concern about their ability to evaluate the risk involved in proposed derivatives transactions. Thirty-one per cent of responding companies indicated a high degree of concern and 36 per cent a moderate degree.

The next most important issue among derivatives users is uncertainty about the accounting treatment for hedges. This is not surprising given the lack of well-specified rules and the importance of such rules to reported results of derivative use. Thirty per cent of organizations expressed a high degree of concern over this issue, with another 30 per cent indicating a moderate degree of concern. In addition to accounting issues, tax and legal issues also generated significant concern.

Finally, the fifth and sixth issues most concerning derivatives users were transaction costs and the liquidity risk of using derivatives. Transaction costs (dealer fees) associated with derivatives generated a high degree of concern for 20 per cent of responding companies while risks concerning liquidity in the derivative markets caused a high degree of concern for 19 per cent of the companies.

Given the popularity of currency derivatives, the survey asked detailed questions about the use of currency derivatives. Businesses were asked to indicate how often they transacted in the derivatives market for six commonly cited rationales for foreign currency risk management: contractual commitments, anticipated transactions of one year or less, anticipated transactions beyond one year, competitive economic exposure, foreign repatriations and translation of foreign accounting statements.

The most frequently cited motivations for transacting in the foreign currency derivatives markets were for hedging contractual commitments (91 per cent hedge frequently or sometimes) and anticipated transactions expected within the year (91 per cent hedge frequently or sometimes).

Anticipated transactions beyond one year were frequently hedged by only 11 per cent of the companies but sometimes hedged by 43 per cent, suggesting that a majority of companies at least sometimes hedge over a longer horizon. Economic and translation exposures were cited by a minority of companies as a reason for using foreign currency derivatives.

Foreign currency hedging is also used frequently to protect foreign repatriations (dividends, royalties/fees, internal interest payments and so on). Thirty four per cent of businesses frequently hedge these flows while another 38 per cent do so sometimes.

Given that not all companies using currency derivatives have foreign operations, this suggests that an even larger proportion of the set of multinational businesses use currency derivatives at least sometimes to hedge the dollar value of foreign repatriations.

Options are widely thought to be better suited than forwards and futures for hedging anticipated transactions, particularly those with longer maturities, as well as competitive/economic exposure.

Consistent with this, more than half of the firms hedging longer term anticipated transactions used options.

Market view on foreign currency derivatives

One area of risk management that has been hard to measure is the degree to which companies alter their strategy based on their view of the direction or level of foreign exchange rates. To gauge the impact of market views on companies’ derivatives activity, the survey asked them to indicate the frequency with which their market view caused them to alter the timing or size of hedges or to actively take a position in the market using derivatives. The responses are presented in Table 2.

Only about 11-12 per cent of organizations reported ‘frequently’ altering the size or timing of hedges based on a market view on the exchange rate. A relatively large number would ‘sometimes’ incorporate their market views into their foreign currency hedging decision, with 61 per cent of firms sometimes altering the timing of their hedges and 48 per cent sometimes altering the size.

Without entering the debate about what constitutes a hedge and what constitutes speculation, it is apparent that a large percentage of companies sometimes take into account their view of future market movements before choosing a strategy. What may be more surprising is the large percentage that ‘actively take positions’ based on a market view of the exchange rate. While only six per cent of firms ‘frequently’ take positions, another 33 per cent do so at least ‘sometimes’.

The survey also asked detailed questions about interest rate derivative usage. A total of 83 per cent of the organizations using interest rate derivatives used these to swap floating rate for fixed rate debt. Nearly 70 per cent of the companies reported doing the opposite. Fifty eight per cent said they used derivatives to fix the spread on new debt issues.

These three motivations are typical of companies that use swaps to tailor their financing needs. Another motivation for using swaps is locking-in borrowing rates (spread) in advance of a debit issue based on a business’s view of the market. About 60 per cent indicated this motivation as being at least sometimes important.

The majority indicated that they undertake interest rate derivative transactions occasionally. This is consistent with these transactions being carried out primarily when businesses undertake financing activities.

We also asked an analogous

A market view on interest

rates causes the company to... Frequently Sometimes

alter the timing of a hedge 8 per cent 64 per cent

alter the size of a hedge 4 per cent 53 per cent

actively take a position 3 per cent 36 per cent

b sags ! | ||

A market view on the exchange rates causes the company to... | Frequently | Sometimes |

alter the timing of a hedge | 11 per cent | 61 per cent |

alter the size of a hedge | 12 per cent | 48 per cent |

actively take a position | 6 per cent | 33 per cent |

question about the impact of a market view of interest rates on the use of interest rate derivatives. According to Table 3, market views seem to have the same effect on the use of interest rates derivatives as those reported for foreign currency derivatives. The impact of taking a market view on interest rates causes a majority of companies to alter the size or timing of hedges and nearly 40 per cent of them to take a position at least sometimes.

Companies obtain derivatives from counterparties ranging from commercial and investment banks to futures and options exchanges. The survey asked companies to rank derivative counterparties based on whether they are a ‘primary’ source, a ‘secondary’ source or not used at all. Commercial banks were rated as a primary source 89 per cent of the time with investment banks second at 44 per cent. Insurance companies were the most common secondary source, mentioned by 30 per cent of the companies. Exchanges were least important to end users; fewer than 10 per cent of businesses listed them as either a primary or secondary source.

To investigate policies with respect to counterparty risk, the survey asked what was the lowest- rated counterparty with which the organizations would enter a derivatives transaction? As shown in Figure 2, for derivatives with maturities equal to 12 months or less 22 per cent of the companies insisted on a rating of AA or above for the counterparty and 73 per cent on A or above.

Policies were even stricter for derivatives with maturities greater than 12 months: 40 per cent of companies insisted on a rating of AA or above.

It is evident that a rating of A or below significantly handicaps a bank in offering derivatives, especially those with longer maturities. Despite this high level of concern about counterparty risk, only one of the 142 companies using derivatives reports ever having experienced a default by a counterparty.

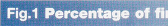

The survey asked two questions about internal procedures regarding derivatives: whether the organization had a documented policy covering the use of derivatives (76 per cent reported having such a policy) and how frequently derivatives activity was reported to the board of directors. Figure 3 shows that 51 per cent of companies had no pre-set schedule while 29 per cent reported to the board either monthly or quarterly.

Derivative transactions

Percentage

AAA AA A BBB <BBB No set

policy

Derivatives as a way of reducing risk

By cross-checking the answers to these two questions, we found that 23 companies, or 16 per cent, indicated having neither a documented policy nor regular reporting of derivative activity to the board.

We were also interested in the organizations’ philosophy for managing derivatives positions. The survey asked whether they viewed their derivatives positions in terms of transactions linked to specific corporate exposures or as a portfolio of derivatives to be managed separately or jointly with the company’s exposure. Just 18 per cent of the firms viewed their derivatives as a portfolio linked to an aggregate corporate exposure while another 15 per cent regarded them as a stand-alone portfolio for at least some purposes.

We also asked organizations that did not use derivatives to provide information on why they chose not to do so. We asked non-users to rank the three primary factors from a list of eight possible factors (including an ‘other’ category).

The most important reason, not surprisingly, is because their exposures did not warrant using derivatives. Nearly 45 per cent of all non-derivatives users ranked this as the most important reason for not using derivatives with an additional 21 per cent citing this as the second or third most important reason.

Another 13 per cent listed the fact that exposures could be managed by other means as a primary reason for not using derivatives while another 21 per cent listed this as the second or third most important reason. Presumably this means the companies could manage their exposure through operating hedges (for example, producing in export markets) or by contractual arrangements which shift or share risk with other parties (for example, pricing in dollars). Other companies, however, refrained from using derivatives even though they were exposed to financial price risk.

The second most popular reason for not using derivatives was a simple cost-benefit explanation - the costs of using derivatives exceeded the benefit. This was cited as one of the top three reasons by 47 per cent of non-users with 12 per cent citing this as the primary reason.

Another interesting finding from this question was that many non-users appeared to refrain from using derivatives simply because of a lack of knowledge. This reason was the second most frequently chosen ‘most important’ factor for not using derivatives, offered by 17 per cent of non-users. This is not just a concern of small companies. While 22 per cent of small companies ranked this as the most important factor, it was regarded as most important by almost as many large-firm non-users at 17 per cent.

Finally, non-users also expressed significant concerns about the perceptions of derivatives. Thirteen per cent ranked concerns about the perceptions of derivative use by investors, regulators and the public as the most important factor in their decision

Fig.3 Derivative a

Frequency of reporting to the board of directors

As needed

Annually No set policy

not to use them. In addition, over one-quarter of the other companies put this as one of their top three concerns.

Derivatives use among non-financial companies appears to be a fact of modern financial life. Despite the derivatives ‘train wrecks’ of 1994, the evidence suggests the percentage of companies using derivatives has not fallen off from 1994 levels. Currently less than half of all non-financial organizations use derivatives, although this is tilted heavily towards larger companies in commodity and manufacturing sectors.

Derivatives are powerful financial tools that can either help or harm. Despite concerns to the contrary, the evidence suggests that the primary reason for using derivatives is to manage (reduce) risk rather than add it. Some companies appear to have a flexible policy on derivative use that allows them to incorporate views on the markets into their risk-management decision. Most businesses, however, said they had documented corporate policies for derivative use as well as established reporting and measurement procedures to prevent abuses and avoid financial disasters in case of large market movements.

Will derivative use increase? Some of the companies not using derivatives may begin to use them as knowledge of these instruments increases and public perception of derivatives improves. In addition, because price volatility appears to be here to stay, companies are likely to make increasing use of derivatives as a tool to manage this risk.

The 1995 survey was sponsored by CIBC Wood Gundy and carried out under the auspices of the Weiss Center for International Financial Research at the Wharton School. The authors would like to thank Charles Smithson for his guidance and support.

The use of derivatives among non-financial companies appears to be a fact of modern financial life, according to the findings of a survey of US businesses conducted in 1995 and discussed in this article by Gordon Bodnar, Richard Marston and Gregory Hayt. Well-publicized debacles in 1994 do not appear to have discouraged respondents.

Despite fears to the contrary the evidence seems to be that the primary use of derivatives (defined here as forwards, futures, options and swaps plus broader contracts that contained one or more of these) is to reduce risk rather than add to it. Most businesses said they had documented corporate policies for derivative use as well as established reporting and measurement procedures. Use of derivatives may increase because of price volatility and as companies’ knowledge of them and public perceptions improve.

O f all the large losses involving the use of derivatives - Barings, Orange County, Showa Oil, Procter and Gamble - few have attracted as much interest as the Metallgesellschaft (MG) case. The problems at MG first surfaced publicly with a report on December 6 1993 in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung alleging that the company was experiencing liquidity problems due to speculation in US oil futures. By the end of the month, the MG board decided to get rid of its chairman and some senior executives; to liquidate $4bn worth of oil supply contracts with customers and in the process to crystallize losses amounting to some $1.3bn.

MG is a large diversified metals, mining and industrial conglomerate. In 1993 it had a turnover of DM26bn ($15bn). Its US subsidiary, MG Refining & Marketing (MGRM), built up a substantial business during the 1980s and early 1990s supplying oil and oil- related products such as diesel, gasoline and heating oil to some 500 large customers including retail gasoline suppliers, manufacturing companies and government departments.

In November 1991, MGRM recruited a new president. Arthur Benson brought with him a 50-person team. Benson had worked for MG’s US operations m the 1980s, marketing oil product contracts until being made redundant in 1988. He had moved to Louis Dreyfus Energy where, in the summer of 1990, a seemingly disastrous position in jet fuel was turned into a rumored $500m profit by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

During the 1980s, worries about the security of oil supplies gradually receded as the price of crude oil dropped from $35 to $ 12/barrel. Then in 1990, with the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, prices doubled from US$18 to US$36 per barrel within days (see Figure 1).

Many oil consumers found they were in a vicious squeeze — supplies disappeared, prices soared and in many cases they were unable to pass on the increased costs in full to their customers.

The Gulf War gave oil distributors and consumers a reminder of the volatility of oil prices and of

Fig.1 Crude oil

Price ($/bbl) 40

m

1986 87

88 89

90 91

Date

92

93 94

the pain caused by a sharp rise in prices. Benson spotted an opening for his salesmen. MGRM would supply agreed monthly quantities of oil products on fixed-price long-term contracts (between five and 10 years). By covering a fraction (typically no more than 20 per cent of their demand) in this way customers could protect themselves in a simple and effective fashion from a sudden spike in the oil price. They could not insulate themselves permanently from a rise in oil prices but they could buy time until they could pass it on to their customers.

MGRM also offered customers the option of liquidating the contracts early if the futures price rose above the fixed supply price. In such a case customers could require MGRM to pay them one half of the difference between the two prices on the remaining volume to be delivered under the contract. This opened up the attractive prospect of being able to turn another oil price spike into a huge cash windfall. At the same time customers could be reassured that a long-term fall in oil prices would not threaten their viability. Since the obligation to buy oil from MGRM at fixed prices would only cover some 20 per cent of their requirements, they would be able to exploit any fall in oil prices on the remaining 80 per cent.

MGRM could not buy the oil and store it to deliver to customers later; financing and storage costs would make the transaction quite uneconomic. Nor could MGRM simply hope that it would be able to buy the oil cheaply when the time came to deliver; oil prices could easily rise by 50 per cent, leading to huge losses. It would have to hedge itself in the financial markets. The obvious instruments to use were the oil futures contracts traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange (Nymex).

By December 1993, MGRM had signed contracts with customers that committed it to delivering some 160m barrels of gasoline and heating oil over a 10-year period (a total value of around $4bn). One third of this (55m barrels) was hedged using Nymex contracts. The rest (110m barrels) was hedged on the over-the-counter (OTC) market through oil swaps. These swaps resembled the Nymex contracts.

Spot oil prices fell from $21.6o per barrel on September 30 1992 to US$13.91 per barrel on December 17 1993. As a direct result, MGRM had to pay out more than $1.2bn on its hedge. The financial problems caused by margin calls were exacerbated in December 1993 by Nymex s decisions to impose ‘supermargin’ (more than twice the normal margin levels) and to revoke MGRM’s ‘hedger exemption’, thus obliging it to put up more cash as security and to reduce substantially its open positions. This was the source of the rumors reported by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. A special meeting of the MG supervisory board was convened on December 17 to consider the preliminary results of investigations by Deutsche Bank and Dresdner Bank (which were large shareholders as well as lenders) into the group’s liquidity. They did not accept the strategy pursued by MGRM.

MG s chairman, Hans Schimmelbusch, was removed after being accused of not keeping the board properly informed of the problems in the US operation. His finance director was also fired, while two other directors were forced into retirement and a further two demoted. Between December 20 and 31, MGRM liquidated most of its futures and swaps positions. It liquidated its forward physical delivery contracts, waiving the amounts potentially receivable under its customer contracts.

MG chairman Hans

Schimmelbusch: ousted following the oil futures debate

The losses at MGRM prompted a fierce debate about whether the strategy was fundamentally flawed or whether it was a good strategy that was prematurely and unnecessarily aborted. To assess the strategy, it is necessary to understand the risks faced by MGRM even after hedging the oil price risk:

• The contracts extended five or 10 years; futures contracts do go out to 36 months but the longer-dated contracts are too illiquid to be of much use. Most of MGRM’s trading was in the near months. This made MGRM vulnerable to variations in the relative price of short- and longer- term contracts.

• The strategy required MGRM to do a lot of trading. At its peak, MGRM’s oil purchase requirements equaled about 20 per cent of the total open interest in the Nymex crude oil futures contract. MGRM was heavily dependent on the continuing depth and liquidity of the market to enable it to roll its positions at reasonable cost.

• The oil products it was contracted to deliver were not identical to the products traded on the exchange. The company was at risk from variations in the prices of different oil products.

• Losses and gains on the futures markets appear as cash immediately; losses and gains on delivery contracts appear at the time of delivery. MGRM was vulnerable to fluctuations in funding costs.

• If oil prices fell (as they did) MGRM would be vulnerable to customers defaulting on their purchase commitments. In the face of all these risks (and with the benefit of hindsight about the size of losses) it is tempting to assert that the strategy was always a gamble. That is not fair.

The strategic concept was quite defensible. There was clearly a demand among customers for long-term fixed-price oil contracts. There was apparently little competition and consumers were not well placed to provide the service themselves. So there was potentially a profitable opportunity to be exploited by someone who could manage the risks effectively.

The question to be asked is not whether the transaction was risky but whether the expected profits were large enough to compensate for the risks and whether the strategy was implemented in a sensible way.

The single most important source of risk (and of profit) for MGRM was the mismatch between the long-term maturity of its liabilities and the short-term maturity of its hedge. To understand the nature of this, consider the following simplified example: MGRM contracts to sell one barrel of oil in five years time. It hedges by buying one barrel of oil six months forward. In six months time, it closes out the position in what is now a maturing contract and buys a new six-month contract. Assume zero interest rates and ignore financing issues - we will come back to these later.

The accountant who keeps the profit and loss account needs to put a value on MGRM’s liability to supply the barrel of oil. He uses the price of the futures contract that MGRM is using for hedging as a proxy for the five-year price. This is not the cleverest or most prudent accounting system. But we are only concerned with the total profit, and that will not be affected by the rule used for valuing the supply contract.

Suppose that MGRM signs the contract at $22/barrel when the six-month futures contract is $20/barrel. The accountant records an immediate profit of $2/barrel. After six months, the price on the contract, which is now near maturity, has gone to, say, $25/barrel. MGRM will have made $5 profit on the rise in the price of the futures. But the accountant will say that this is exactly offset by an increase of $5 in the cost of meeting its commitment to supply. So the hedge appears to be perfect.

But now MGRM has to liquidate its futures position and buy one of the new six- month contracts. Suppose that the six-month contract is trading at $24/barrel - $1 less than the spot. As MGRM switches contracts, the accountant will reduce the valuation on MGRM’s liability to supply from $25 to $24 - so creating a profit of $ 1/barrel. A revaluation will occur every time the hedge is rolled forward. By the end of five years, the total profit made by MGRM will therefore be the sum of two components: the difference between the contract price and the spot price; and the difference between the spot price and the six-month futures price each time the contract is rolled over.

MGRM s profits depend on whether the market is in ‘backwardation’ over the life of the supply contracts. Backwardation is when the price for longterm delivery falls below the price for immediate delivery.

Over the period 1986 to 1992 the degree of backwardation averaged some $0.14/barrel/month (see Figure 2). Had MGRM written a contract to supply oil in five years time at a price equal to the current spot price and had it hedged by rolling short-maturity futures contracts, it would have generated a profit of $8.40/barrel.

Fig.2 Backwarda

Price differential ($/bbl) 1 month future - 2 month future 1.00

1986 87

88

89 90

Datp

91

92 93

94

This may exaggerate the potential gain since it includes the Gulf War when backwardation was enormous. If that period is ignored, the average level of backwardation is halved. But even profits of $4 per barrel are substantial.

Backwardation has been quite persistent but its causes are not well understood and it might not persist at historic levels. The very fact that customers were prepared to buy oil long-term at or above the spot price when the term structure of futures prices is downward sloping suggests a degree of disequilibrium that would attract other traders to follow MGRM. This could well lead to a decline in backwardation.

MGRM’s strategy meant that it had to be in the market on a permanent basis, rolling out of its position in maturing contracts into slightly longer-dated contracts. Such a strategy was likely to affect the prices it faced given the large amounts with which it was operating and this too would tend to reduce profitability. Historical evidence gives grounds for believing in continuing backwardation and hence in the profitability of writing long-term contracts at or above current prices. But there was never any certainty that MGRM’s strategy would be profitable.

There were substantial risks in a strategy of hedging long commitments using short- dated futures. My calculations suggest that on the most favorable assumptions, the risk was likely to be around $3/barrel. That is to say, if MGRM hedged as closely as possible, hedging changes in the slope of the term structure as well as in its level, it could easily end up making $3 more or less per barrel than expected. Thus, even if the future broadly resembles the past, it is likely that the strategy will fail to make money. The fact that the best hedge is not very good affects the financing of the position. If the hedge is demonstrably a good one, there is likely to be little problem in getting a bank or other institution to finance it. They are lending against an asset whose value is known to exceed the debt. But if the hedge is risky, a bank will not finance it because it would bear the loss if things turn out badly without sharing the profits if they go well. The strategy needs to be financed with equity.

MG itself needed to set aside enough capital to absorb potential losses; otherwise it faces the risk of having to liquidate its position prematurely. It requires that the strategy be understood throughout the company and by its investors, and this understanding appears to have been lacking.

MGRM seems to have bought one barrel of futures for every barrel of oil to be sold. This would lead to overhedging for two important reasons.

First, a $1 increase in the spot price of oil is unlikely to imply a $1 increase in the price of delivery in five years. Many factors might affect the short-term supply/demand balance that have little significance for long-term prices. Over 1993, the spot and near- term futures moved down far more sharply than longer-term futures (see Figure 3). The losses on the hedge were far larger than the expected profits on the supply contracts.

The second reason is that a $1 fall in the oil price at all maturities costs the company $1 today on the futures market; the corresponding $1 gain in the supply contract only occurs when the oil is supplied.

The overhedging means that MGRM was net long oil; as the oil price fell it was actually losing money. If the minimum risk hedge was 0.5 to 1 rather than 1 to 1, then

10 • Derivatives

roughly half the loss that MGRM incurred was due to the fact that, intentionally or not, it had a huge exposure to the oil market when the oil price was falling very sharply.

The most difficult question to resolve is how much of the loss can be attributed to the decision to unwind the contracts at the end of 1993. Customers were committed to buying large volumes of oil from MGRM at what was by then a huge premium to the spot price.

These contracts seem to have been terminated without MGRM extracting any value from them. Yet in theory they were valuable to MGRM - worth many hundreds of millions of dollars.

Realizing this value required a continued hedging program, with the associated financing; it would not have been riskless - there was always a fear of customer defaults. Yet it is hard to believe that the best solution was to tear them up.

MGRM’s role was similar to that of a financial intermediary. It recognized that clients were prepared to pay a premium for a service above its fair market value. It designed a product to meet that need and a hedging strategy that passed most of the risks to the market. It kept some risks that it managed in house.

The problems appear to have been of two kinds. First, MGRM took on, intentionally or not, a huge amount of oil price risk that it need not have done. It is not clear that it had any particular expertise in guessing the level of the oil price. Second, MGRM did not ensure it had enough capital to hold to its strategy as the market moved away from it. It was trying to exploit a deviation between the price at which customers were prepared to buy oil and its estimate of the equilibrium price.

Large and persistent deviations can only be exploited with some risk. If deviations exist, they can get worse. An institution seeking to exploit them needs to have the financial strength to see the transaction through to the end; a forced exit is almost bound to be costly. In MGRM’s case that meant having the commitment and understanding of both its parent and its bankers. The parent needed to understand and accept the risks it was taking and the bankers needed to be convinced they were lending no more than could be confidently recovered from customers. Clearly this was lacking.

Few derivatives disasters have inspired as much interest as the case of Metallgesellschaft - the metals, mining and industrial conglomerate which lost $1.3bn in 1993. In this article Anthony Neuberger explains the background to the story and draws some important lessons.

He argues that given clear customer demand for long-term fixed-price oil contracts the strategic concept was perfectly defensible - the question is not, therefore, whether

Fig.3 MGRM's p

S3

Table captionNYMEX crude oil futures prices (Price $/bbl)

24 | ||

22 | — 01 Sep 92 = 01 Dec 93 | |

,■ ' • 1 """ . 1 ■ 1 Y — 11 ■' " "i |

18

Maturity (months)

Metallgesellschaft: a hedge too far

the transaction was risky but whether the expected profits were large enough to compensate for the risks and whether the strategy was sensibly implemented.

The problems, he believes, were of two kinds: intentionally or not the US subsidiary took on a huge amount of oil price risk which it need not have done; second, in trying to exploit a deviation between the price at which customers were prepared to buy oil and its estimate of the equilibrium price, the company did not ensure that it had enough capital to hold to the strategy as the market moved against it.

Canter, M.S. and Edwards, F.R., (1995), ‘The collapse of Metallgesellschaft: unbridgeable risks, poor hedging strategy or just bad luck?’, Journal of Futures Markets, May, 15(3).

Culp, C.L. and Miller, M.M., (1994), ‘Hedging a flow of commodities with futures: lessons from Metallgesellschaft’, Derivatives Quarterly, Fall, 1, 7-15.

Culp, C.L. and Miller, M.M., (1995), ‘Metallgesellschaft and the economics of synthetic storage’, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Winter, 7(4).

<*