The bakery wakes in spring, peaks in summer, winds down in fall, and sleeps in winter. The deepest part of the coldest month is suited for reflection. A time when the experiments of last year are evaluated, celebrated, and laid to rest. The silence draws out a nostalgia. I have come to this place several times, as many iterations of myself. Personalities layered like a stack cake. Although I traveled the country baking professionally through my twenties, baking has evolved into my own personal practice. The rituals and rhythms of flour, water, and fire allow me to process a changing world. This little strip of land has watched me become a woman.

What I refer to as the bakery is two buildings, one my home, and the other, a one-room kitchen with an outdoor Alan Scott oven and tiny upstairs apartment. The space was transformed by Jen Lapidus into a bakery in the late nineties under the name Natural Bridge; my role here is to steward a timeless mission once printed on Jen’s bread bags: TRUTH, LOVE, AND GOOD BREAD. At some point it will be passed to the next wayward baker. I am but a housekeeper sandwiched between a historical reenactment and the future in which economic systems have collapsed and we are returned to our own two hands. I make the most of my time. And occasionally watch it slip through my fingers.

When I first passed through the door, Jen was already absent. Dave Bauer, hailing from Wisconsin, had reclaimed the space under the name Farm & Sparrow and was making what was rumored to be the world’s best bread; I sought him out. Borrowing a car, I drove the thirty minutes from Asheville to Madison County: the jewel of the Blue Ridge. I got lost, of course. Finding a row of men sitting in front of a bar that was also a general store that was also a tea shop, I inquired for directions. They called the bakery by various names—it was indeed familiar. One had done the electrical. Another remembered building the oven. The most I gathered was keep going.

Drive through the junkyard past the rafting company. Take a left between the fire station and the hairdresser. At the end of the tobacco field, take a right. Go past the abandoned gas station. If you reach the river, you’ve gone too far. Watch out for the dogs that chase cars and the rooster in the road. Take a left at the teal mailbox.

People weren’t lying. The bread was good. Some of the best I’d ever tasted. Naturally leavened. Starters made with 100 percent whole-grain flour. Wet, loose dough. Hand shaped. Long fermentations. Blazing hot oven. It was my first glimpse of how breads and ovens evolved together: a whole working ecosystem of flavor. I left the next day to take a baking job on the West Coast, carrying a loaf of seeded bread onto the plane and consuming it feverishly.

I came back. This time to work at Farm & Sparrow creating pastries and granola and bagging the holy grail of bread. I eventually followed Dave when he relocated, and the little one-room shop went dormant. In the passing of time, I struck out on my own, learning how to farm and selling bread and tarts at the local market, illegally baking out of a barn in an oven that stood on wobbly cinder blocks. By then Jen had started running her mill, Carolina Ground. When I met her there to pick up flour, she suggested I consider leasing the space, and we came out to the vacant bakery to discuss its future. It needed to be cleaned and resurrected, but it had potential. I scrubbed it on my hands and knees. Washing away my own traces.

The last time I arrived was an internal entrance in the spring of 2015. I was baking pies, and my longtime lover walked out. For good. I went to the door, opened it, straightened my apron, and busied myself with the painstakingly slow process of healing.

There is an undeniable magic here. It must pour from the watering can dangling amidst weathered branches. Or maybe it emanates from the fallen barn behind the roses. Dusty pieces of wands and toys lace the yard. When the cement floor around the oven was poured, Jen and her daughter pushed in tiny mirrors and gemstones. Visitors bend over to try to pick them up. This place is like that: a shiny penny in rough bramble, hard to extract.

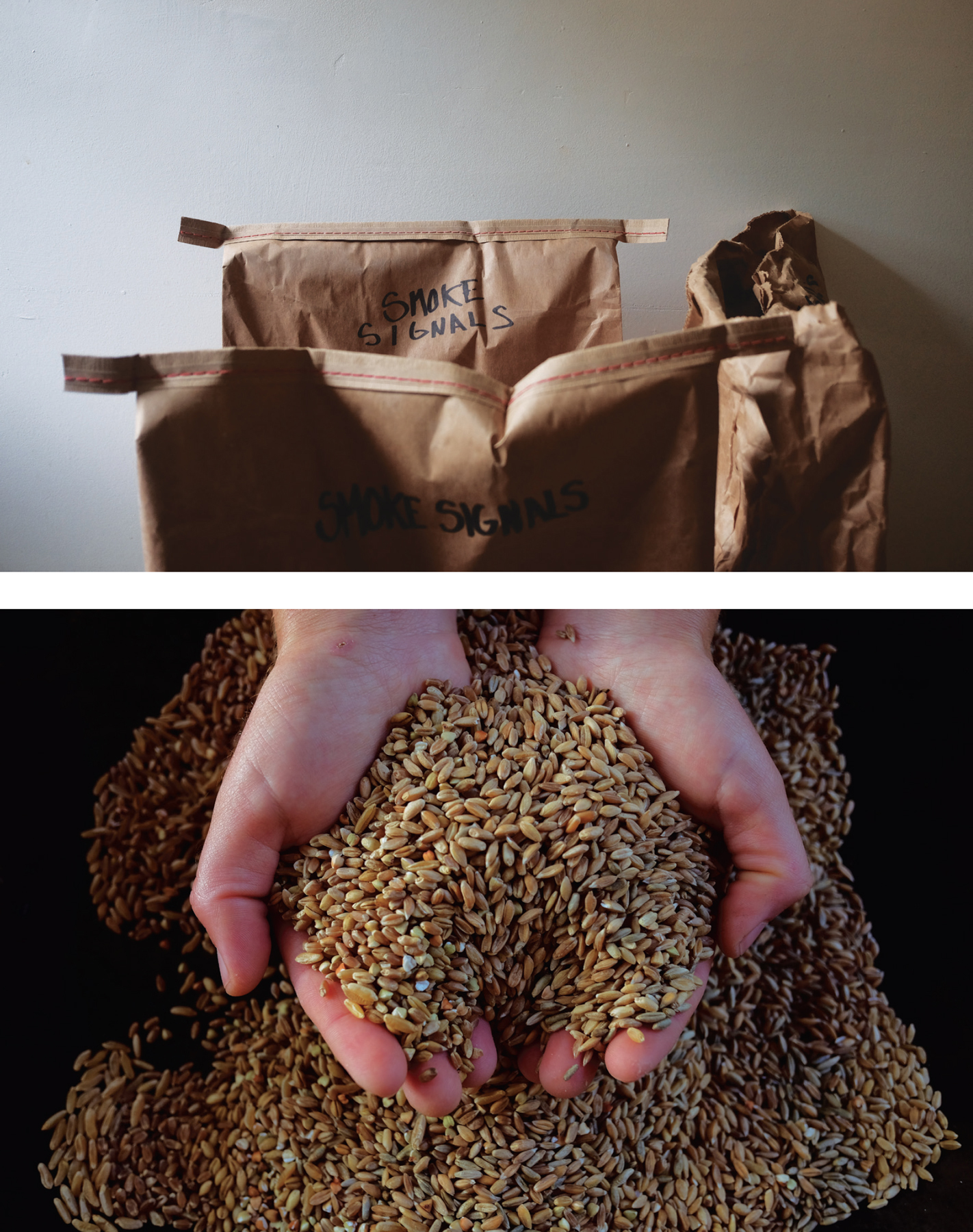

Above the workspace, the guest rooms smell like summer camp. I go there in the cold to lie down and inhale. It calms me. I watch my breath curl in the frigid air. The smell is my friend. The way the light falls is my friend. The milk truck. The bags of grain. The rocking chair. The polyester quilt. The woodpile. The dying pond. The picnic tables. These are my companions.

Everyone who has lived here left an imprint. Scratches on the door: tattoos of a dog asking to be let out. Lines on the wall: a child marking height. Stray piles of bricks: a mason taking lunch. Bleached-out floor: the shadow of where a mill once stood. My addition is a wooden triangle at the end of the drive, along with four deep grooves in the living room floor under my writer’s chair.

Nothing has taught me how to bake more than simply living here. Positioned in the center of a swirling wheel, I mark my hours by chopping wood, feeding cultures, and making fires. Although I am alone here, I am not the only living thing. The starters bubble and gurgle with temperamental yeast, and the flames crack and boom against the fire brick. Each loaf pulled from the hearth is a record of sunlight, stone, and sentiment.

When the temperatures drop, my main responsibility is to keep the pipes warm. The landscape here is jarring. Tight passages mean portions of the road never see the sun. I think twice about leaving. The pantry becomes important. Pickles. Coffee. Flour. Sugar. Nuts. Popcorn. Spices. Vinegars. Oils. A few bottles of wine. Bags of onions. A sack of garlic. A basket of squash. And, of course, jars of grain.

Wheat is no more wheat than an apple is an apple. Every variety has a particular texture, flavor, and aroma. Variations expand based on growing practices, milling styles, and preferences in preparation. Get to know the nuances of each variety. It will change everything about how you bake. Like making a friend, what was once ill-defined and unknown becomes unique and special.

Modern wheats fall into roughly three categories:

Hard or soft.

Hard grains are higher in protein and suitable for bread making due to their ability to trap gas and hold it over a long period of time. Soft grains are lower in protein and best for pastry or dough where a weaker gluten structure allows gases to pass through. The bran of hard wheat is brittle, and when stone milled, cracks into the flour, making it difficult to remove entirely and creating a radiant golden-brown flower. The bran of soft wheat is tender, coming off in large swaths between the millstones. Larger portions of bran lead to easier extraction culminating in a light, creamy-toned flour.

Red or white.

Red wheats have a deep rosy hue and tannins in the bran building a robust, peppery, and occasionally bitter taste in whole wheat goods. White wheats have a fawn or straw-colored bran, achieving a sweeter, milder flavor even with 100 percent of the bran present. Red wheats are higher in protein—perfect for naturally fermented, chewy, hearth breads—while white wheats, lower in protein, shine in crispy crackers, toothy noodles, and lush pan loaves.

Winter or spring.

In regions with mild winter temperatures, wheats are planted in the fall before Thanksgiving and harvested at the onset of summer. In bitterly cold climates, spring wheats are planted after the last frost and processed in the fall. In general, spring wheats have higher levels of protein and a more elastic quality.

As a basic grass, wheat is designed to nourish itself, protect itself, and reproduce. The germ, endosperm, and bran each play a role in this unfolding mission. In seed form, wheat has been a vital storage crop to many cultures, crossing oceans and continents in pockets and jars. However, once crushed into flour, it should be used as fresh as possible to honor the flavor and aroma.

The smallest portion of the berry, the germ, is packed with fats and fragrant oils. The embryonic heart, it is from here the taproot sprouts and growth begins. The endosperm makes up the majority of the overall berry, a starchy and protein heavy storehouse providing long-term nutrition as the grass grows. Residing in the endosperm are two important proteins: gliadin and glutenin. When hydrated, these proteins lock together in a web-like structure called gluten. Gliadin is responsible for the extensibility in a dough, while glutenin imparts elasticity. The bran, the visible outer coating of the berry, is a shield against the wilds.

TYPES OF GRAINS AND CEREAL CROPS

Einkorn, emmer, and spelt.

These wheats compose the trinity of grains that fall under the umbrella farro. Known to be aromatic and oily, as well as nutrient rich, these sister grains store amazing flavor, yet structurally the gluten is fragile and viscous.

Einkorn is the oldest cultivated wheat and the parent to many varieties. Found in the tombs of ancient Egypt, einkorn is a taut, flat, fawn-colored grain. Milled, einkorn flour is incredibly creamy and supple. Fragrant and fluid, einkorn flour is sticky when hydrated and quick to ferment.

Emmer is the second oldest cultivated wheat. A medium-size ruby-beige grain with flavors running from a vanilla bean sweetness to a mouthful of starchy potato. Although firm, it’s tender enough to sink your tooth into. Milled, emmer flour is slightly coarse and smells pleasantly like a barn. Emmer is commonly used in pasta.

Spelt is the largest of the farros. Chew it raw for a milky, honey taste. Whole-grain spelt doughs ferment well and have a taffy-like quality. Hildegard von Bingen, a twelfth-century German nun, claimed that eating whole spelt would not leave the body emotionally drained due to its intense nutritional qualities.

Kamut.

Also known as Khorasan wheat, kamut is large and golden, with a buttery bite. Milled, kamut has a gritty texture and looks like sunshine ground into a bowl. At once crispy and chewy, it is incredibly high in protein and works well in both pastry and bread, imparting a toasted corn sweetness.

Buckwheat.

The seed of a tall, slender plant related to rhubarb and sorrel, buckwheat contains no gluten. High levels of starch and oil make an incredibly silky flour that can stand alone in pancakes and crepes. Intensely nutty, buckwheat often finds a good home in pastry.

Barley.

This straw-colored, round berry has an earthy, mineral flavor. Eaten worldwide in soups, porridges, and teas, barley has a spongy texture and absorbs liquids well. Unlike other grains where the fiber is mostly present in the bran, the fiber in barley is pervasive through the entire grain. Roasted, it is extremely sweet.

Rye.

This blue-green grain grows favorably in cool climates. Not technically a wheat, rye possesses a vegetable gum that mimics gluten and is responsible for the slick nature of unbaked rye bread. Dense rye breads can taste grassy and dank and have a cakelike crumb. Fluffy and almost purple, rye flour can be used in sweet and savory goods.

Corn.

While fresh corn is considered a vegetable, the dried seed is classified as a grain. Corn is high in vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Known for its intense color, the red, largekerneled Bloody Butcher is a bakery favorite, while standard popcorn is a staple in my kitchen cupboard.