(1959–)

HE IS A BIG MAN, AND HE SAYS “BAM” A LOT. For most people, that’s enough to instantly conjure an image of the outsize chef that sent a shock of the South through mainstream American cuisine in the nineties, a man no less Southern for being born in Fall River, Massachusetts, some thousand miles north of the Mason-Dixon. Emeril Lagasse is indelibly linked to his adoptive home of New Orleans, where he took over the legendary Commander’s Palace at twenty-six, reshaping the revered but stodgy New Orleans culinary scene. His seems to be a simple, if maximalist, philosophy: that food could be made more exciting with the unrestrained application of spices, hot sauce, and catchphrases, as well as a liberal sampling of global cuisine. His particular brand of New Orleans cooking, dialed to eleven, rolled through the country by way of his TV show, and he happened to become the archetype of the modern celebrity chef in the process. “Kick it up a notch” became a culture-wide tagline for a reason: Emeril asked, and taught his audience to ask, how whatever dish they had in their kitchen could be elevated to some next level. And once it was there, hey, why not kick it up another notch?

LAKE FLATO IS A SAN ANTONIO ARCHITECTURAL firm lauded for its designs that blend groundbreaking sustainability and place-specific, down-to-earth modernism. Lake Flato buildings often incorporate skillfully welded structural steel—a material as indigenous as lumber in oil-field-rich Texas; some Lake Flato buildings incorporate salvaged drill-stem pipe—and always prioritize outdoor living. The firm’s first commission, a weekend retreat in South Texas, was “more porch than house,” according to Ted Flato, who cofounded the firm with David Lake in 1984. Fresh out of the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture, the pair worked for the legendary Texas architect O’Neil Ford, a self-professed “pre-modernist.” Like their mentor, Flato and Lake put great stock in the wisdom of their antecedents—reliance on local materials and craftsmen, and the ways older shelters overcame the Southwest’s blistering summer sun, winter winds, and long dry spells. You could call Lake Flato “pre-green,” since the firm’s sustainable leanings predate the green-building revolution. Since then, the firm has evolved to incorporate the most advanced technology to model and measure buildings’ impact on the environment. But the original instinct—responding to place with simple, beautiful, meaningful designs—still drives the work. Rather than beat back sun and wind with energy-intensive mechanical systems, Lake Flato designs often harness and leverage those natural forces using breezeways, covered outdoor kitchens, courtyards, and porches.

The firm is known for its Porch House concept, which involves site-designing a compound of modular rooms linked by breezeways and other connective tissue. Lake Flato even managed to apply its philosophy to San Antonio’s ATT Center, home court of the NBA’s Spurs. The architects designed tall porches, loggias, and deep overhangs to soften the coliseum’s exterior. Corner stairs wrapped in perforated metal, like sunscreened silos, pull in air for better circulation. An exterior plaza invites visitors outside for beer and tacos. The metal sombrilla shading the plaza—a classic Lake Flato detail—was inspired by something Lake saw while driving past a hot, dusty cattle yard: a makeshift shade strung up with cables and cast-off sheets of roofing tin.

HARPER LEE PUT LANE CAKE ON THE CULINARY map in 1960, when To Kill a Mockingbird’s heroine, Scout Finch, describes her neighbor’s booze-soaked confection as “loaded with shinny.” But actually this decadent cake, layered with bourbon, butter, and raisin filling and topped with fluffy egg-white icing, dates back to the late nineteenth century. Originally a West Georgia treat, having first appeared in Clayton native Emma Rylander Lane’s self-published 1898 cookbook, Some Good Things to Eat, the Lane cake’s popularity eventually spread into Alabama and its surrounds. More than a century later, it remains a staple of church socials and other community gatherings. No need to serve it with an after-dinner drink—this spirited dessert stands firmly on its own.

A PIG STORES FAT ALONG ITS LOINS, IN ITS shoulders, and in a thick casing along its back. There is ruffle fat by the intestines and caul fat near the stomach. But the finest porcine blubber is soft, pure white leaf fat from around the kidneys. Once rendered, it becomes the king of lard. With its high smoke point, leaf lard makes an excellent frying fat, yet its greatest value is to pastry makers. Generations of Southern bakers became masters of piecrust and biscuits thanks to its mild flavor and creamy room-temperature texture. For decades, lard served as the primary cooking fat in the South, cheaper and more readily available than butter or nut oil. But amid misguided health concerns, many bakers switched their allegiance to hydrogenated vegetable oil, aka shortening, in the mid-twentieth century. It wasn’t until dietitians and health experts let out a collective “oops” in the 1990s amid studies showing the health risks of trans fats that home cooks began returning to animal fats like lard and butter. You can find jars of leaf lard in gourmet shops; alas, it has become an expensive alternative.

(1926–2016)

WRITERS, I HEAR, GET TO BE FAMOUS IN a quiet kind of way. I have yet to see one depicted on a T-shirt. Their posters appear mostly in libraries, bookstores, and orderly literary festivals, printed with good grammar and dignified fonts. People will applaud them, with polite enthusiasm, and might even line up to see them, for a signature or a handshake, but rarely do they push, hoot, or jostle, even for the most famous of them. Nelle Harper Lee was too private, much of her life, even for such as that, and this was part of her great mystery.

I knew a young writer who wanted to meet her. To him, as with so many of us who call ourselves writers, she stood at the zenith of what we wanted to be, for she had written a book that mattered, that had, even in some small way, changed the world. The young writer just wanted to step onto her porch in Monroeville, and, in a perfect world, see the lady herself open the door and say . . . well, anything, “Hello,” or “May I help you?” or even “Get off my damn porch.” I cannot recall exactly what happened, but I believe he did seek her out, and she was polite to him, as I recall.

Me, I was too proud. I waited till I was almost an old man myself, to go see her. And when I did, I spoke just a few moments about nothing at all and then left too soon, because I was too polite. I left with questions unasked and the great mysteries unsolved. I doubt if she would have told me any of them anyway, if I had been of a pushy mind. But she was kind, and complimentary, and told an Auburn joke, and though it was already clear that macular degeneration and a profound deafness had begun to imprison her, her legendary wit was still there, and that was a fine gift on a spring afternoon, in a small, hot room in a quiet retirement home in Monroeville, Alabama.

It is widely known that people who knew her called her Nelle.

I think I never called her anything but ma’am, and mumbled that. And then, not long after, in February of 2016, she was gone.

But this, in remembering your idols, may not be the worst it could be.

Published in 1960, To Kill a Mockingbird was a kind of gospel, north and south, appealing, through the beauty of story, for us to be better than we were, to live up to our finer natures, and not our baser ones, to rise inside our own consciences and not wallow in the mob. I have written that it was not a cure. The meanness depicted in its story endures and, in the modern day, still often triumphs. Yet the hope in it lingers on, and on.

One of the few who did know her, who shared his thoughts with her in writing, was the respected professor, historian, and author Wayne Flynt, who, with his wife, Dartie, corresponded with her across decades, beginning in 1993. In that fine meantime, they wrote of the world as they saw it, of catfish, Mobile eye doctors, Hebrews 13:8, hateful infirmity, C. S. Lewis, Zora Neale Hurston, whether or not Baptists will tell a lie, and if someone told Truman Capote that Kennedy had been shot, he would have claimed to have been driving the car. She asked, in writing, if he would preach her funeral.

He did know her.

“Two things I talked to her about,” Dr. Flynt said, “I could never tell while she was alive.”

One would seem easy, yet has been debated by scholars for decades: What was Mockingbird’s theme?

To her, it was simple. It was not just about race, though that will always be the part we most cut ourselves upon, but about all kinds of justice, and fairness, and a sorting out of what it means to get into someone’s skin and walk around in it. You never gain any understanding, in a pluralistic society, until you do. She expected smart people, like Flynt, to know this.

In a time “when we needed it as an insight to race, she told it to us in a way that seared our conscience,” said Flynt, who is also an ordained Baptist minister.

The other one, of why she did not more quickly follow with another book, is still not perfectly clear, even after years of friendship. He believes it is not one answer but many, including the fact that she was never sure she could write a book of such quality.

“Then she looked at me with those sparkling, inquisitive eyes,” he said, and told him, more or less, she didn’t have to. Then, only at the end of her life, came the sequel, written not after Mockingbird, but before.

Flynt put his and his wife’s correspondence with Harper Lee into a lovely book called Mockingbird Songs, to, finally, “let her voice become part of the conversation,” he said.

The best thing about that long friendship was its depth, and that was also its pain. It broke his heart as her deafness and blindness closed in, and confusion followed, to the point she could not always recognize the people she knew that she should know. It is the price you pay, for the joy of it.

Most of us have only what Harper Lee gave us, which was 376 pages, in paperback.

My niece, Meredith, read the book for the first time recently. When I asked what she would remember, she said “the knothole,” where Boo Radley left the treasures for the children to find, before it was filled in with cement, to try to kill a friendship that could not be so easily killed.

Everyone has something that stays inside them, from this book. I hear that when Tennyson died, they rang the bells in London all day, longer. Every time I hear a bell, I think of Tennyson.

Every time I hear a mockingbird, I wish I had stayed longer in that hot little room.

(1916–2006)

AMONG PEOPLE WHO MET THE CHEF AND author Edna Lewis or who knew her, there’s a constant refrain: how regal she was. Very like a queen. Tall, erect, strikingly beautiful, with a beatific smile and a great mane of steel-gray hair, often swathed in a shawl of West African pattern, she did fit that description. And, like her British royal counterpart, soft-spoken, a very decorous, calm, and courteous queen. Imposing but never imperious. This natural nobility sprang from two sources: a pedigree of rich American roots, and an imaginative and skillful culinary mastery.

She was born in 1916, in a small part of Virginia founded and occupied by former slaves and their descendants, appropriately known as Freetown. Freetown gave her the gifts of a lifetime. As her classic 1976 book, The Taste of Country Cooking, makes abundantly clear, it gave her a heritage not just of food, but also of traditions and community. The people of Freetown ate sustainably, locally, and farm to table long before those became marketing buzzwords. In direct, supple, and elegant prose, Lewis took the reader to the groaning board of the African American picnic. The Taste of Country Cooking is recognizably Southern, but even more, recognizably American, which is the generous lesson Lewis gave us. That book was published well before the renaissance of Southern cooking in the 1980s, when it came to the forefront on the world stage as a legitimate fine cuisine—before chefs such as Larry Forgione in New York, Stephan Pyles in Dallas, Jeremiah Tower in San Francisco, Mark Miller in Santa Fe, Paul Prudhomme in New Orleans, Jasper White in Boston, and Bill Neal in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, received international recognition and won major awards. Lewis’s book also seemed to rhyme with what the Berkeley, California, chef Alice Waters had been doing and saying about using fresh, local, organic foods—ushering in a new American whole-foods diet.

Edna Lewis, it would seem, was destined from early on to become a legend, in culinary circles at least. Having left home at sixteen, she wound up in New York by way of Washington, D.C. In the late 1940s, at Café Nicholson on East Fifty-Eighth Street, she was cooking for Southern expatriates (the likes of Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, and William Faulkner) and for other bigwigs—Marlon Brando, Richard Avedon, Gloria Vanderbilt, Eleanor Roosevelt, Greta Garbo, Salvador Dalí. She was known for simple yet dynamically delicious fare: perfectly roasted chicken, seafood prepared with wine, cheese and chocolate soufflés; always mindful of what vegetables were in season, of freshness, and above all of flavor. It would take decades, though, for Lewis to receive the broader recognition befitting her accomplishments. After Café Nicholson closed, she would go on to cook at Gage & Tollner in Brooklyn, the Fearrington House Restaurant outside Chapel Hill, and Middleton Place in Charleston, South Carolina.

Her legacy goes beyond her books, which include (in addition to The Taste of Country Cooking) The Edna Lewis Cookbook (1972), In Pursuit of Flavor (1988), and The Gift of Southern Cooking, which she cowrote in 2003 with the lauded chef Scott Peacock before her death in 2006. Now we have the Edna Lewis Foundation, a nonprofit (in the words of its founder, the chef Joe Randall) “dedicated to honoring, preserving, and nurturing African Americans’ culinary heritage and culture.” And a generation of chefs, cooks, and food writers—some of whom are only now coming to recognize her regency, their debt to her, and her great good gifts.

(1935–)

TAKE A GANDER AT THE ICONIC 1956 PHOTOGRAPH taken at Memphis’s Sun Studios of the “Million Dollar Quartet”—Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis—and it’s hard to square that Lewis is the last surviving member. Already known as a hell-raiser both on the piano and in his personal life, Lewis shot to early rock-and-roll superstardom with the indelible hits “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” and “Great Balls of Fire” before scandal erupted over his marriage to a thirteen-year-old cousin. Years playing in the beer-joint wilderness followed, punctuated by the deaths of two later wives under mysterious circumstances, his conspicuously dropping an f-bomb at the Grand Ole Opry, and an infamous arrest for ramming his Lincoln Continental into the gates at Graceland. Induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986 helped return Lewis to the firmament, followed by a 1989 biopic in which he was portrayed to the hilt by Dennis Quaid. These days, the octogenarian formerly known as the Killer likes to watch old Gunsmoke episodes at his ranch near Memphis, but when he takes the stage at a Mississippi casino or a hip London club, it doesn’t take long for that old fire to light up his eyes—and the ivories.

(1940–)

HE WOULD LATER SAY IT WAS THE MOST frightened he’d been in his life. Which was saying something. As twenty-five-year-old John Lewis led six hundred people across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in March 1965 to walk from Selma, Alabama, to the capital, Montgomery, to protest barriers to black voter registration, he had already endured round after round of violence in his quest to defy injustice. Inspired by the Montgomery bus boycotts and their engineer, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., he was hit while sitting in at segregated Nashville lunch counters as a college student, punched in the face in Rock Hill, South Carolina, and knocked unconscious with a Coca-Cola crate in Montgomery as one of the first thirteen Freedom Riders testing the Supreme Court ruling that barred segregation of interstate transportation hubs. As one of the organizers of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, he refused to strike back every time he was threatened, or beaten, which was often; still, he was arrested some forty times in the sixties alone. But on that Bloody Sunday in Selma, when his skull was fractured by the business end of a billy club as a line of 150 Alabama state troopers brutally advanced on the peaceful marchers, horrifying a nation, his courage helped lead to, days later, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s taking landmark voting rights legislation to Congress—the Voting Rights Act was signed into law that August.

Heroes are often defined by one act. One bout of bravery, whether on the battlefield or at a burning car on the highway. But John Lewis never stopped to rest on his laurels. Instead, this son of Alabama sharecroppers dedicated his life to securing human rights and civil liberties, driven by his moral convictions and his desire for what he calls “the beloved community”—a society free from the burdens of race. In 1986, more than twenty years after he helped MLK organize the March on Washington, at which he gave a keynote speech at age twenty-three, he brought the movement back to the nation’s capital when he was elected to the House of Representatives representing an Atlanta district. There, he has served for three decades, fighting for the likes of health care for the uninsured, LGBT rights, and a museum to honor the contributions of black Americans. That dream was finally realized in the fall of 2016, when the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opened on the Mall. President Barack Obama added the highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, to Lewis’s cavalcade of honors and awards over the years, a list that now includes a National Book Award, for the third in his coauthored best-selling trilogy of graphic novels called March, which depict the civil rights movement through Lewis’s eyes. Not bad for a man who was once denied a library card as a boy in Troy, Alabama. See Edmund Pettus Bridge.

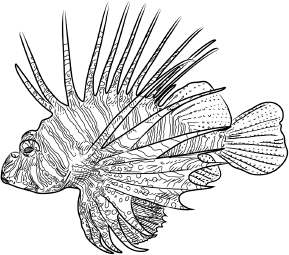

ORNERY FISH WITH VENOMOUS SPINES, LIONFISH don’t play well with others. The invasive swimmers—natives of the South Pacific and Indian Oceans and popular aquarium specimens—are spreading like the plague: first spotted off the coast of Florida in 1985, they’re now established as far up the Atlantic coast as North Carolina, and throughout the Caribbean. Scientists say they’re feasting so ravenously on native fish including grouper and snapper that they’re becoming obese. Now, humans are biting back. Fishermen gather for lionfish derbies in Florida and elsewhere, and coastal chefs have begun putting them on the menu in an effort to dent the population. Given that the fish must be speared one at a time, they don’t come cheap or easy, and the outlook for eradicating them from the reefs they’ve colonized is pessimistic at best. On the upside, their light, buttery meat is positively luxurious.

OFFICIALLY THE SOUTHERN LIVE OAK, Quercus virginiana, the beloved and iconic coastal hardwood spreads its blessings from Virginia to East Texas. It’s a shade provider, an air-conditioner, and a source of provender for wildlife—woodpeckers, fish crows, sundry ducks, turkeys, squirrels, bears, coons, deer—and in the olden time, people (their crushed acorns make tolerable mush and passable flat-bread, once you get the bitter leeched out).

A live oak can take a lightning bolt, droop and wither a few days, then come back as good as new. Wildfire can burn the heart right out, roaring up into the trunk, throwing smoke and sparks like a steam engine at full throttle . . . and the tree will still live another century.

Colonial shipbuilders loved live oaks, hewing the gentle swoop of the limbs into ribs, and making the crotches into brackets and the trunk into hull planking. Live oaks from Georgia’s St. Simons Island built the USS Constitution, laid down in 1797 and named by George Washington. Sailors called her Old Ironsides after British cannonballs bounced off her live oak in 1812. She’s still afloat.

Cut a live oak at your peril. The trees are often protected, and the law might make you replace it “inch for inch.” A sixty-inch live oak equals eight saplings at about two grand each. Plus freight. Plus labor.

YOU’VE PROBABLY HEARD THE OLD CHESTNUT about American Indians using every part of the bison, from hide to horns. Below the Mason-Dixon, the hog is our tatanka. You name it, we’ve eaten it: ears, snout, feet, tail, and, yes, liver. In and around Shelby, North Carolina, the pork-liver-and-cornmeal loaf known as livermush in fact remains a staple. Fans keep the product on supermarket shelves in both Carolinas, even as a new generation far removed from the family farm and menus that make the most of the hog finds it hard to swallow. Most people eat livermush on a plate with grits and eggs, or on biscuits with mustard or jelly, but it isn’t just for breakfast. At Mush, Music & Mutts, an annual livermush festival in Shelby, you’ll find everything from livermush pizza to livermush fried rice. One thing all livermush lovers can agree on, though: it should be sliced thin and fried hard, in plenty of butter. Because despite the name, “mush” isn’t the goal.

(1915–2002)

THE SOUTH’S INDIGENOUS SOUNDS—BLUES, gospel, jazz, bluegrass, zydeco—are such an integral soundtrack of the region that we’ve sometimes taken them for granted. God bless Alan Lomax for knowing better. Starting out at the age of seventeen with his father, John, the native Texan spent much of the 1930s and 1940s documenting the various strains of American folk music for the Library of Congress. He was exhaustive to the point of obsession, happily hauling a bulky three-hundred-pound recording machine deep into Appalachian hollers and Delta cotton fields if tipped off that there was an authentic voice to be found there. His so-called field recordings captured prison work songs and sacred choirs, banjo pickers and slide-guitar innovators, and, incredibly, he was the first to record the seminal figures Lead Belly, Muddy Waters, and Woody Guthrie. The interviews Lomax also conducted showed the artistry of his subjects and his deep respect for them. To help folk music find an audience (as Lomax put it, give “a voice to the voiceless”), he became a radio host and record producer, but continued his forays afield into the 1990s. Today, the Association for Cultural Equity has digitized more than seventeen thousand audio files from his collection. Ethnomusicologists (as they are now called) will study those recordings forever—though Lomax would most likely tell his acolytes to get out and spend some time on the back roads, too.

AS STATE NICKNAMES GO, THE LONE STAR State beats the hell out of Land of Enchantment and America’s Dairyland. (Sorry, New Mexico and Wisconsin, you had your chance to do better.) It helps that the nickname’s origin predates the state of Texas itself, even if the meaning is a bit fuzzy. What historians do know is that when early Texans fought to gain independence from Mexico (you remember the Alamo, right?), they devised flags bearing a single large star. To some that star may have represented Texas’s brief status as an independent republic; to others it may have expressed a desire to join the United States. Texas did just that in 1845, and in 1889 adopted an official flag that prominently featured a lone star. Today it represents the still stubbornly independent spirit of Texans, but it is ubiquitous, emblazoned on everything from license plates to steakhouses. You can even ask about the state nickname in just about any bar in Texas and be handed a cold beer. Which probably doesn’t work in Oregon—the Beaver State.

ONCE THE DOMINANT TREE OF SOUTHERN coastal plains, longleaf covered ninety-three million acres from Virginia to Texas, forests that were dependent on brush fire for their regeneration (longleaf seeds will not germinate unless cracked by fire). It takes a century to grow a longleaf sawlog, but it’s worth the wait. The wood of Pinus palustris is fine grained and beautiful, unbelievably strong, rot resistant, and termite proof. In 1538, the de Soto expedition walked for days through cathedral groves.

Today the trees are mostly gone. The forests were stripped after the Civil War and longleaf timber went around the world, shoring up European mines and framing Buckingham Palace. An entire ecosystem went with it—panthers, bears, ivory-billed woodpeckers. A scant million acres of longleaf remain, the rest replaced by yellow pine planted and harvested like corn. It takes only twenty-five years to make a crop of yellow pine, fated to become toothpick timber, chipboard, and paper. But groups such as the Longleaf Alliance are pushing to bring the original trees back—five acres, ten, a hundred at a time. Meanwhile, there is a booming business in recycling longleaf timbers from factories, warehouses, and mills into flooring, wainscoting, and countertops. Run your hands across a thirty-inch board and count the rings: right back to de Soto.

THEY LEFT THE ROOM UNTOUCHED, JUST the way it looked on that terrible day. The rumpled bedspread. The old rotary phone. The scattered coffee cups in their saucers. The mod sixties furniture, set against a wall of knotty prefab paneling. The black-and-white TV, rabbit ears tuned to the staticky world. You stand behind the Plexiglas divider, and see the room more or less the way Martin Luther King Jr. left it when he cinched his tie and headed out the door—and into martyrdom.

The tableau is simple, even mundane, and yet it grabs you: personal effects transform into relics; period pieces become stand-ins for the souls who last occupied the space. A freeze-frame of the precise moment an era ended.

At a little before six o’clock in the evening, on April 4, 1968, the civil rights leader emerged onto the balcony and stood in front of the now-iconic turquoise door, Room 306. Did he realize how vulnerable he was up there? Did he have a premonition of his own death? “I may not get there with you,” he’d said the night before. But “we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

From a motel corridor, you gaze at the brick rooming house where James Earl Ray brandished a .30-06 rifle from the window of a grungy bathroom. You look down at the balcony floor, where King fell with a ragged wound to his neck and jaw. You try to imagine what really happened at that moment, and what larger plots may have been churning in the margins of history.

The Lorraine Motel—home of the National Civil Rights Museum, which has recently undergone a $27.5 million renovation—is something every Southerner, every American, every human, needs to see. Any place erected on the site of an assassination is liable to skew toward the macabre, but somehow the Lorraine doesn’t. Set among warehouses and railroad depots in downtown Memphis’s South Main Historic Arts District, the Lorraine is a pilgrimage shrine—holy ground with an ineffable power.

For a long time, through the seventies and eighties, many of the town fathers lobbied to tear down what was then a ratty, vice-ridden haven for addicts and prostitutes—an embarrassment, they said, and an eyesore. But for a handful of forward-thinking people, the Lorraine would have succumbed to the wrecking ball. Dedicated in 1991, the museum has become one of the city’s greatest attractions, with more than 265,000 yearly visitors. “This is everybody’s museum,” the NCRM’s president, Terri Lee Freeman, has said. “What it should do, frankly, is light a fire under us.”

And it does. People come here from around the world to contemplate the power of nonviolent protest. Others come to enact rituals, exorcise demons, and expiate sins. There’s a reason the Lorraine has been visited by the likes of the Dalai Lama and Nelson Mandela and Bono. The museum—and especially Room 306, the heart and soul of the enterprise—has a haunting potency that must be experienced to be understood.

Just below the balcony, beside a finny vintage Cadillac permanently parked in the lot, a stone marker proclaims: “Behold, here cometh the dreamer . . . let us slay him . . . we shall see what will become of his dreams.” And yet it’s here, at the very spot where he fell, that his dreams feel most emphatically alive.

SACRED GROUND IN SOUTH CAROLINA AND Georgia, the Lowcountry hugs the coast, stretching from the Sea Islands to the Sandhills (the eastern edge of South Carolina’s Midlands). Roaring surf, pungent dead-end creeks, bright brimming inlets, and lazy rivers. Blue crabs, mullet, redfish, sea trout, and shrimp. Oaks, plantations, palmettos, pine, porpoises, and 7,500 square miles of some of the loveliest country on earth. Charleston, the Holy City, is its undisputed capital.

Beauty was nearly the Lowcountry’s undoing, as several hundred thousand folks have relocated here, making it the fastest-growing region in the country many years running. But thanks to public/private initiatives, half this coast will remain forever wild.

THE LUNCH COUNTER, ONCE COMMON IN DEPARTMENT stores across the region, was not a Southern innovation. Like the space itself, the foods typically served there, from club sandwiches to hamburgers and fries and apple pies, were more broadly American than specifically Southern. Lunch counters became sacred Southern spaces on February 1, 1960, when four black college students at North Carolina A&T—Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond—took seats at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro and ordered coffee and pie that never came.

Blacks had previously protested segregated service in Southern restaurants. Perseverance distinguished this effort. When they were rejected, the students didn’t leave their counter-stool perches. They literally sat in, determined to wait out the white waitresses who refused them coffee and subvert the Jim Crow laws that dictated second-class treatment of black citizens.

Woolworth’s closed early on that winter day. Twenty more students joined the next day. By the end of the week, the crowd of activists neared three hundred. Word of the sit-ins spread, and demonstrations began in Winston-Salem, Wilmington, and south of the border in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Within two months, students in more than fifty cities had staged sit-ins.

There was power in their protest. Reflecting on the moment, McCain, who died in 2014, said, “Fifteen seconds after I sat on that stool, I had the most wonderful feeling. I had a feeling of liberation, restored manhood; I had a natural high. And I truly felt almost invincible.”

There was also power in the lunch counter. Sharing a meal signaled social equality in the Jim Crow South. Like sex, eating was perceived as a deeply intimate act. And no eating space was more intimate than the lunch counter, where diners stooped to take their seats and eat with neighbors and strangers alike.

Instead of integrating during the four-year-plus struggle that began in the winter of 1960, some lunch counters closed. Others removed their stools. Writing in the Carolina Israelite newspaper, Harry Golden unpacked the absurdity of the moment. “It is only when the Negro ‘sets’ that the fur begins to fly,” he wrote, proposing a tongue-in-cheek solution. The Vertical Negro Plan called for refashioning segregated sit-down lunch counters into integrated stand-up restaurants.

Golden was being playful. But the stakes were high. And so was the drama. In Jackson, Mississippi, a 1963 Woolworth’s sit-in escalated into one of the most violent of the era. When an integrated group led by college students attempted to gain service, a mob of white counterprotesters threw salt in their eyes, dumped mustard on their heads, and dragged one protester to the floor, where they kicked him repeatedly.

When President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law on July 2, he outlawed segregation in restaurants and other places of public accommodation. The law restored dignity to black patrons of white restaurants and set the stage for a modern restaurant industry that now thrives in the South.

After a long absence, Southerners have returned to communal dining. Large unbroken tables—introduced as class equalizers during the French Revolution, copied by American hotels in the nineteenth century, and interpreted as lunch counters in the twentieth—are regaining popularity. At the Beatty Street Grocery, a Jackson, Mississippi, café that abuts a scrap-metal yard, white construction workers in brogans and black government bureaucrats in cap-toes gather today at high-top counters to eat fried bologna sandwiches on toasted white bread. Fifty years after the South desegregated its restaurants, shared meals like these showcase the rapid pace of change in the region and the promise of the welcome table ideal.

(1932–)

SHE WAS BORN A COAL MINER’S DAUGHTER IN Butcher Hollow, Kentucky, became a young wife and mother who turned her life with a philandering husband into country gold, and is now revered as the Queen of Country Music. Brash hits such as “Fist City,” “The Pill,” and “Rated X” were girl-power anthems in the 1960s and ’70s, ones that conservative country radio programmers wouldn’t touch. “I was just singing about what was going on,” Lynn once said. “They weren’t used to hearing a woman talk like that. Well, they found out with me!” In later years, her fearless attitude attracted the likes of the rocker Jack White, who produced her 2004 Grammy-winning comeback album, Van Lear Rose, and her plainspoken, straight-shooting songs have inspired a legion of present-day female country music stars, from Miranda Lambert to Kacey Musgraves.

PIONEERS OF A DRIVING, POWERFUL, THREE-GUITAR Southern rock sound, the band was dismissed by early critics as boozy, sloppy, and self-indulgent. With thirty-five million records sold and indestructible hits—“Sweet Home Alabama,” “Free Bird,” and “Gimme Three Steps,” perpetually in heavy rotation on classic rock radio—Lynyrd Skynyrd (named for a Gainesville, Florida, high-school phys-ed teacher who hated long hair) is having the last laugh. The band was discovered by the musician and producer Al Kooper in an Atlanta nightclub in 1972. Within a year, a debut album, (Pronounced ‘Lěh-’nérd ’Skin-’nérd), had gone gold and the band was opening for the Who on a national tour. Between 1973 and 1977, they released five highly successful albums. Three days after the release of Street Survivors in 1977—with the album’s cover presciently featuring the band members surrounded by flames—a chartered plane carrying band and crew crashed near Gillsburg, Mississippi, killing singer and main lyricist Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines, and backup singer Cassie Gaines. Most of the survivors were seriously injured, and no band recorded under the name Lynyrd Skynyrd for ten years. The original band has remained controversial, some branding them racist rednecks, others defending them as misunderstood. “Sweet Home Alabama,” for example, contains a famous swipe at Neil Young, although in fact the band and Young were friends and admirers of one another’s work. In the cover shot of Street Survivors, you can just make out that Van Zant sports a Neil Young Tonight’s the Night T-shirt beneath his jacket.