SOUTHERN HOSPITALITY OWES A LOT TO ICEBOX desserts. Frozen concoctions of gelatin, condensed milk, and whipped cream sometimes shot through with fruits and nuts, they don’t need a hot oven. That’s a blessing on steam-bath summer nights. And there’s no struggling with burned crusts or underbaked fillings, as cooks raised on pies and puddings discovered after the midcentury advent of the refrigerator. Like ice cream, icebox lemon pies and strawberry-and-cream delights exit the freezer ready to be divvied up and enjoyed. What’s more, they tend to be multicolored, multilayered showstoppers worthy of a dinner party finale.

A FOREIGN-SOUNDING TERM THAT OFTEN REFERS to a peculiarly sugarless beverage that is unfamiliar, unpalatable, and possibly incomprehensible to many native-born Southerners. See Sweet tea.

THE DARK BLUE DYE EXTRACTED FROM INDIGO grown in the Carolina colony was once one of the most sought after commodities in the world, second only to rice as South Carolina’s foremost plantation cash crop in the years before the Revolutionary War. Historians have compared its profitability to the silver mines of Mexico or Peru during the same span. But selling indigo was the easy part; cultivating it was another matter altogether, relying heavily on slaves’ labor and skillful knowledge to produce the prized dye. A few notable eighteenth-century planters, including a teenage Eliza Lucas Pinckney, achieved success and fortune, contributing to an annual export that reached more than a million pounds by 1775. The industry declined rapidly following the Revolution, giving way to cotton by the 1800s. In recent years, however, a few devoted small-scale producers have begun experimenting with the dye, which for all its dark history produces an undeniably beautiful color.

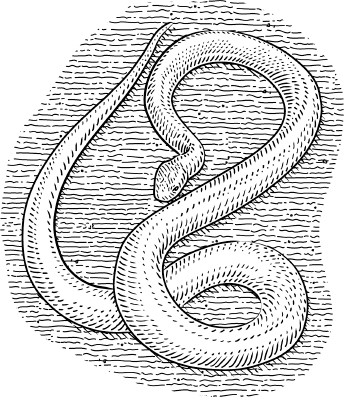

FIRST OF ALL, THIS DARKLY GRACEFUL REPTILE is actually a glossy black or metallic purple, making the indigo snake one of nine million American things that are named in a way that is abjectly misleading (see: pineapple). But aside from that, it has earned a reputation as being mythically, almost spiritually alluring. Indigo snakes are nonvenomous and generally friendly, though you’d be forgiven for not immediately wanting to cozy up to an iridescent eight-foot-long metallic purple predator. In addition to their docility, they’re defined by unhingeable jaws (which dislodge to make it easier to gulp down frogs, rodents, and other snakes), intelligence (which is noted by fans and collectors), and status as the country’s longest native snake species. But mostly, it’s the look: dark and radiant, a glowing black with crimson-orange touches on its face. That look is also partly why they’re vanishing. Indigos are on the brink of extinction, displaced by development, reduced by hunters who damage their habitats in search of rattlesnakes, and depleted by the pet trade. The species was granted federal protection in 1978, and remains listed as federally threatened in its usual home states of Georgia and Florida.

I NSECTS THAT EXIST FOR REASONS OTHER than to suck the blood of people have a multitude of uses. The main daily quandaries of any Southern rural childhood are twofold: Where are the snakes one has to kill today, and where are some june bugs, so that they can be captured, have strings tied around their legs, and then “flown” on the leash? Those insects that can be bent to one’s will are the mainstay of constructive biological experimentation for the Southern child in the wild—for instance, catching a cricket, which can then be used to motivate a fish to take a hook in a creek. Tying strings around a june bug’s legs—without ripping them out—was the more difficult trick.

The nuanced, experienced june-bug torturer—such as my brothers and me—quickly noted that success was often built on the thinness and flexibility of the string. This would be the early-school theory of fishing lines of different weights for different fish, because the play is not to inhibit their flight by weighing the tiny beings down with a heavy line. Thus if one sacrifices a few to the learning curve, one gains a kind of fly-tying expertise, and june bugs, in particular, will survive for hours to become one’s very own Beelzebub, the little green devil’s helper buzzing around on its leash from the hole in your T-shirt. It was an early badass move, walking through the day having a june bug fly around your head, the eight-year-old’s equivalent of having a live-action miniature green motorcycle on your shoulder.

JACK-MULATER—ALSO KNOWN AS WILL-O’-THE-WISP, fox fire, and jack-o’-lantern, of which the term is most likely a Gullah variation—is one name for the ghost light of Southern swamps and hills. Theories and haunting legends abound. A Confederate soldier looking for his lost head on Land’s End Road (in Beaufort County, South Carolina)? Cherokee maidens seeking out dead warriors by torchlight up and down the east side of Brown Mountain (along the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina)? Many have seen it, but few can explain.

Scientists tried, but the closest they got was to give ghost lights a name: ignis fatuus, Medieval Latin for “foolish fire.” The Italian physicist Alessandro Volta, the Englishman Joseph Priestley, and the Frenchman Pierre Bertholon de Saint-Lazare, great minds of the late 1700s, pegged it as methane gas from decaying vegetation ignited by static electricity. Modern science suggests most ignis fatuus results from the oxidation of phosphine (PH3), diphosphane (P2H3), and methane (PH4), which can cause photonic emissions. Got that?

Something else to consider: Chemistry fails to account for the ghost light’s apparent intelligent behavior. It rarely appears to large groups, mostly to lone travelers. When approached, it retreats, often leading the unwary to peril. If the traveler retreats, the light is sure to follow.

Maybe sometimes it’s just easier to believe in ghosts.

(1911–1972)

DESPITE BEING BORN INTO A NEW ORLEANS household so poor that her longshoreman father had to moonlight as a barber, Mahalia Jackson held on to hope. “Blues are the songs of despair,” she explained when asked why she didn’t chase money in the secular sphere. “Gospel songs are the songs of hope. When you sing gospel, you have the feeling there is a cure for what’s wrong.” In 1927, at age sixteen, Jackson moved to Chicago, where she cleaned hotel rooms, washed clothes, and sang with the choir at the Greater Salem Baptist Church. By the mid-1930s, she was touring with Thomas A. Dorsey, who introduced jazz rhythms and the autobiographical language of the blues to gospel music. His “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” became Jackson’s signature song, although she sold more copies of “Move On Up a Little Higher.” Jackson’s faith in better days ahead remained so sturdy that she took notice when a Southern preacher sermonized about his utopian vision. A few weeks later, seated behind him on the dais at the March on Washington, Jackson urged, “Tell them about the dream, Martin!” Martin Luther King Jr., departing from his prepared remarks, did just that. More than six thousand people attended Jackson’s funeral in 1972 in her adopted home of Chicago. Her friend Harry Belafonte called her “the single most powerful black woman in the United States.”

JAMBALAYA IS THE PAELLA OR PILAU OF bayou country. Cajun and Creole recipes follow the same steps: First, sauté the holy trinity of bell peppers, onions, and celery with the meat—chicken, smoked sausage, and shrimp are popular choices. Then add rice and stock and simmer until done. Creole cooks might add a few urban flourishes along the way, such as chopped vegetables and tomato. Cajun cooks might add wild game. Whatever recipe you follow, this is a rice-and-seafood dish fit for beginners—made in one pot, and easier to master than a roux-based étouffée or gumbo.

THE BEST DEFINITION OF JAZZ IS SAID TO HAVE come from none other than Louis Armstrong, the New Orleans trumpeter who arguably served as a definition of the thing in himself. “If you gotta ask,” he supposedly said, “you’ll never know.” Most say it grew out of the singing, dancing, and drumming at Sunday slave gatherings in New Orleans’ Congo Square, where African rhythms began to form the backbone of a new style that drew on traditions from all over the world. But one reason jazz is hard to define is its utter disregard for convention: Jazz likes to bend notes out of shape; it uses offbeat, syncopated rhythms to keep you on your toes; it prefers a loose structure full of improvisation over anything too regimented. Jazz absorbs influence, from Africa, from the Caribbean, from the Mississippi Delta; from chamber, classical, and marching music; from everything else. It uses a lot of brass and woodwinds but also might not. Jazz might be the big bands of the 1920s, the hypercool virtuosos of the sixties, or those soft tones leaking out of elevator speakers. It has been called the only true American art form, the baseball of music. It’s a distinction to which jazz, by nature, would most likely pay little heed.

TO BE OFFICIAL: IT’S THE NEW ORLEANS Jazz & Heritage Festival Presented by Shell, which nobody ever calls it except the local papers, and one suspects they only do so under some pecuniary duress involving threat of withheld advertising. Everyone else just calls it Jazz Fest, as they have since it was first staged in 1970.

The festival was initially conceived by the New Orleans Hotel Motel Association to boost tourism. The association sagely hired George Wein, the producer of the Newport Jazz Festival, which started in 1954, to organize it. Wein, in turn, recruited help from the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University, which lent him a staffer, Allison Miner, and a student intern, Quint Davis. Both assisted in producing the event the first year; both joined the staff to oversee the festival’s tremendous growth thereafter. Miner worked for the festival until her death in 1995; Davis is the current producer and director.

The first festival took place at Louis Armstrong Park at the edge of the French Quarter and featured a gospel tent and four stages. Performers the first year included Mahalia Jackson, Fats Domino, the Preservation Hall Band, Duke Ellington, Clifton Chenier, and Al Hirt. Admission was three dollars. Approximately 350 people attended.

Word spread about the quality of music, and the festival quickly outgrew the park, moving after two years to Fair Grounds Race Course, about three miles from downtown, where it remains today. The event now takes place over seven days at the end of April and the beginning of May. It unfolds across a dozen stages of varying size, plus several more intimate stages where musicians are interviewed and cooks demonstrate recipes. Nearly a half million people now attend over the course of the week, with ticket prices running about seventy-five dollars for a full day.

Jazz Fest features headliners whose connection to jazz is not immediately evident: Paul Simon, Drake, Elton John, Willie Nelson, Bruce Springsteen, Kenny Chesney. Longtime fest veterans shrug this off, noting that the one Springsteen attracts thousands of attendees who effectively subsidize the dozens of local trad-jazz performances staged with less fanfare at the smaller venues. Anyway, the festival was started to celebrate jazz’s birthplace, but it has always encompassed all forms of music—rock, pop, blues, gospel, and country.

The “heritage” part of the festival takes several guises. Artisans from Louisiana and beyond vend their creations at booths, and craftsmen display forgotten skills such as ironmongery and violin making. The grounds often erupt in music and dancing as Mardi Gras Indians and “second-line” bands parade through. Food is also a significant draw—dozens of vendors hawk local specialties, including many perennial favorites available chiefly at Jazz Fest, among them the Cochon de Lait po’boy, Crawfish Monica, and Mango Freeze (a tasty sorbet).

Critics sometimes gripe that Jazz Fest has settled into a slightly slouchy middle-age rhythm, which is not surprising for an event well into its fifth decade. While it still attracts attendees of all ages, gray-haired folks dressed in floppy straw hats and bright aloha Jazz Fest shirts visually dominate (new official patterns are released annually). Fest veterans often wear their old shirts as badges of honor, like tattered rock tour T-shirts, although Jazz Fest shirts look more laundered and one guesses that plastic storage tubs may be involved. As such, Jazz Fest has evolved into something of a secret society of baby boomers who still appreciate a good tune.

OVER THE LAST THREE HUNDRED YEARS, THE art of celebrating the end of a life by staging a catharsis of music and dance has been honed to perfection in New Orleans. Sundays were days off under the eighteenth-century Code Noir, the French-colonial body of law governing slavery, so that Congo Square, the plaza within today’s Louis Armstrong Park in Tremé, could host fabulous West African orchestras and dance-offs. The brass band entered the African American musical lexicon with military marches in the 1800s. By 1900, what outsiders called a “jazz funeral” had taken on the soaring narrative architecture we know today. The slow march out to the grave site musically states the passing, after which the body is, in New Orleans parlance, “cut loose,” or severed from the embrace of the community at burial. Exuberantly, with flourish and flair, the band and procession then work back to a boisterous wake, followed as ever by the “second line,” who promenade with their own drummer. Taken as a dramatic progression from a state of grief to the state of joy—a wholesale reversal of tragedy—the jazz funeral mimics the soul’s imagined arc from the body to the heavens. In doing that, it has become one of this world’s most eloquent, defiant essays on Death’s own march, addressed to the celestial powers and to those left behind.

(1893–1929)

A PILLAR OF COUNTRY BLUES, WITH A LEGACY OF both influence and a string of hits in the 1920s, Blind Lemon Jefferson was born on a cotton farm outside of Couchman, Texas. Known as the “father of Texas blues,” Jefferson was blind from birth and one of seven children, and though exact dates are hazy, around 1912 he began playing guitar at area picnics and gatherings, taking cues from local players but also absorbing the flamenco-influenced sounds of Mexican workers. His eerie, lonesome-sounding voice, ribald (for the time) lyrics, and intricate guitar work on songs like “That Black Snake Moan” and “Matchbox Blues” brought him success from Dallas to Chicago and directly impacted the works of fellow bluesmen including Lead Belly and Lightnin’ Hopkins. He cut more than a hundred original songs during his run, one that was tragically cut short when he was found dead on a Chicago street in 1929.

(1743–1826)

FOR MANY, THOMAS JEFFERSON EMBODIED the ideals of the Southern gentleman. A Renaissance man brimming with curiosity and passion, he was an agrarian innovator, garden tinkerer, naturalist, philosopher, inventor, public servant, architect, writer, and able musician, equally as fond of wine and warm company as intellectual pursuits. Jefferson, more than any other founding father, shaped the future trajectory of the United States. He authored the U.S. Declaration of Independence and served his young democracy in many roles, including Virginia governor, U.S. vice president, foreign ambassador, and president for two terms. In 1803, he led the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France, a masterstroke that gave the United States control of the Mississippi River.

A Southerner, Jefferson was a fierce advocate for his region following independence, when distinctions between North and South came into sharper focus. He opposed Federalism, fearing the agrarian South would lose influence. Still, he could be self-deprecating and hard on his kind. In a 1785 letter to the Marquis de Chastellux, Jefferson wrote that “in the north” people were cool, sober, laborious, and chicaning, while “in the south” they were fiery, voluptuary, indolent, unsteady, generous, and candid.

Jefferson was far from perfect. Though he was a visionary leader and artful politician who fiercely defended individual rights and intellectual freedom, he kept upwards of two hundred enslaved blacks as property. They boosted his bottom line while working without compensation, tending his fields, laboring in his nailery, and keeping house. He kept one, Sally Hemings, as a concubine and fathered six of her children. In his writings, Jefferson condemned slavery as “this great political and moral evil,” yet throughout his life he freed only seven males, all members of the Hemings family.

For all his brilliance and worldly refinement, Jefferson was not a fancy man. He felt that the president should dress and act in a way that reflected the simplicity and informality of the country. Leave the pomp and circumstance to European royalty. Dinner guests arriving at the White House were often shocked by his disheveled appearance and threadbare slippers. He seated dinner guests, regardless of social status, on a first come, first served basis. On one notorious occasion, the wives of British and Spanish diplomats had to scramble for the best seats.

Two centuries later, Jefferson’s practicality and humility come off as refreshingly authentic. He was down-to-earth. Offered a third chance at the presidency, he declined, writing to a friend: “Never did a prisoner, released from his chains, feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power. Nature intended me for the tranquil pursuits of science, by rendering them my supreme delight.”

At sixty-five, Jefferson returned to Monticello, his beloved Virginia mountaintop estate, but his ambition never diminished. Among other things, in his later years he founded and designed the University of Virginia, which accepted capable students, both wealthy and poor.

The university opened in 1825. Jefferson died in 1826. He left directives for his burial at Monticello, stipulating a simple monument made of coarse stone. It was to read:

Here was buried Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of

American Independence

Of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom

And Father of

the University of Virginia

And “not a word more . . .,” Jefferson instructed, “because by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered.”

A SONG, A CHARACTER, AN EPITHET, A SYSTEM of oppression—that’s the evolution of Jim Crow. Named after a racist tune and archetype created by a white minstrel performer named Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice in 1830s New York, the term became synonymous with a series of laws and customs that disenfranchised, terrorized, oppressed, and segregated African Americans from white populations, largely in the South, for almost a century.

After the Civil War, Reconstruction—the federal military occupation of the Southern states that had seceded from the Union—forced Southerners to grant voting rights to black men per the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, and entities such as the Freedmen’s Bureau, which sought to help former slaves make the transition to freedom, fueled white resentment. After the troops withdrew in 1877, Jim Crow rules reared their heads. An 1890 Louisiana law separating blacks and whites on railroad cars provided the first test. When the U.S. Supreme Court upheld that discrimination in the landmark 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson, its decision cemented the acceptance of “separate but equal.”

From there, Jim Crow seeped into every aspect of daily life. In various cities and states across the South, the list of things blacks and whites could not do together ranged from rules imposed and enforced by law—marrying; attending school; serving in the military; riding a bus; being buried in the same area of a cemetery; living in the same neighborhoods; and even playing checkers—to unwritten codes of “etiquette” meant to underscore white supremacy (a black man, for instance, couldn’t offer his hand first to shake with a white man). Breaches of those customs were often met with intimidation and violence such as lynching, or the threat thereof, by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. In the meantime, black voting rights took a substantial hit, thanks to expensive poll taxes and laws that excluded, for example, those who couldn’t read. In 1954, the Supreme Court finally overturned Plessy with its decision on Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, ruling that the “equal” part of “separate but equal” was rare and that segregated schools were inherently detrimental to minority students.

Over the years, influential civil rights activists emerged from efforts to fight Jim Crow, including Ida B. Wells, a Mississippi native who condemned lynching through her newspaper column; Rosa Parks, whose refusal to give up her bus seat to a white person sparked the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott; and Martin Luther King Jr., whose nonviolent protests sparked the beginning of the end of Jim Crow, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both of which greased the wheels of desegregation first set in motion ten years earlier.

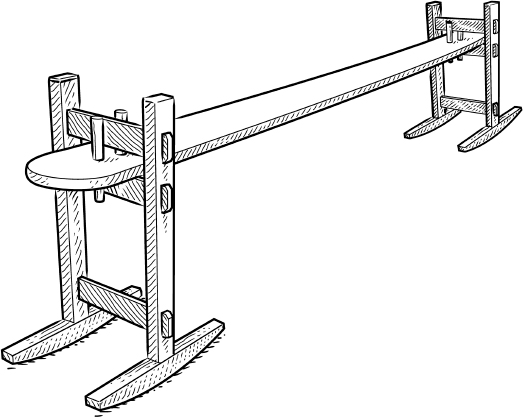

A HISTORICALLY INSPIRED PIECE OF OUTDOOR furniture—part garden bench, part rocker, part swing—the joggling board has long been a fixture on porches and piazzas in Charleston, South Carolina. Simply made, it’s a long, pliable pine plank, traditionally thirteen inches wide, supported by rocking legs on either end. The effect: a bench that bounces and sways—but doesn’t break—when you sit.

Popular local lore contends that the first joggling board appeared in 1804 at Acton Plantation, the home of Cleland Kinloch, in Sumter County near Columbia. When Kinloch’s wife passed away, his sister Mary Benjamin Kinloch Huger arrived to help care for the household. At the time, she suffered from debilitating rheumatism that prevented her from exercising, and so after relatives in Scotland, as the story goes, sent plans for a bench on which she could gently bounce, the plantation carpenter got to work. Before long, the narrow bouncing boards were gracing porches across the Lowcountry. One hundred fifty years later, they were nowhere to be found. If not for Tommy Thornhill, a Charlestonian who began building them in his basement in 1959 after a fruitless search of antique and furniture stores, they might have vanished altogether. Thornhill, who founded the Old Charleston Joggling Board Co. in 1970, not only helped revive them, he also gave them their now-signature color: the not-quite-black historic hue known as Charleston green.

(1911–1938)

AT THE INTERSECTION OF ROUTES 49 AND 61 IN Clarksdale, Mississippi—probably the world’s most famous crossroads—the legendary bluesman Robert Johnson is reputed to have sold his soul to the devil in exchange for mastery of the guitar. Myths and stories about Johnson abound, mostly because he left little behind but two (definitive) photographic portraits and twenty-nine recorded songs. In the 1997 film Can’t You Hear the Wind Howl?, Johnson’s friend and fellow musician Johnny Shines took issue with the most famous legend. “He never told me that lie,” Shines said. “If he would’ve, I would’ve called him a liar right to his face. You have no control over your soul.” Another Mississippi-born bluesman, Son House, claimed that Johnson actually annoyed audiences with his poor guitar playing in his early days. Johnson fled “to Arkansas or someplace,” returning six months later a changed player. What remains today is the singularity of both his guitar playing and his almost terrifyingly haunting voice. Both of them have influenced generations of musicians. Eric Clapton calls his singing “the most powerful cry that I think you can find in the human voice.” When Brian Jones played Keith Richards a Robert Johnson record, Richards’s first question was “Who is the other guy playing with him?” There was no other guy playing.

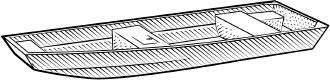

WHAT THE HUMBLE JON BOAT LACKS IN LUXURY, it makes up for in utility, a floating testament to the adage that less can indeed be more. Typically made of aluminum, with a flat-bottomed hull, square nose, one or more bench seats, and a slight updrift at the bow, a jon boat is lightweight, maneuverable, and ideally suited to shallow waters, where it can get to places bigger, fancier boats often can’t. And while you’ll find these nearly indestructible workhorses from coast to coast, they’re a mainstay of hunters and fishermen across the South.

The origin of the name is a matter of some debate, though a popular theory traces it to a variation of “jack boat,” a flat-bottomed craft popular in the Ozarks in the early twentieth century. However, it may also relate to its longtime reputation as an everyman boat—a boat for every John. Regardless, the jon boat has survived the test of time, favored by those who don’t require a boat to look sexy as long as it gets the job done. Which accounts for an oft-repeated bit of Southern wisdom: if you really want to figure out where the fish are biting, follow the guy in the jon boat.

(1931–2013)

FRANK SINATRA ONCE SAID THAT GEORGE Jones was the second-best vocalist he’d ever heard, and there is perhaps no more adored male country singer. With an unbelievable delivery that soared and rumbled with equal aplomb, Jones’s voice was spectacular, milking every syllable for sonic gold on hits like “White Lightning” and his 1980 smash “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” which topped the country charts for eighteen weeks. He was just as adept at singing harmony, sharing the microphone with stars such as Waylon Jennings, Buck Owens, and Merle Haggard, along with recording nine albums’ worth of collaborations with his onetime wife Tammy Wynette. Jones—given the nickname “Possum” by two radio programmers because of the shape of his nose and facial features—was also infamous for his struggles with alcohol, including the oft-told legend of him driving his riding lawn mower to the liquor store after his second wife, Shirley Corley, took away the keys to all of their cars.

SOUTHERNERS COOK WITH A CORNUCOPIA OF salt pork products: bacon, hocks, fatback, and jowl. Cut from the cheek, jowl is a cured and smoked product that’s kin to continental guanciale. Fried like bacon or diced as seasoning for pintos and field peas and other vegetables, it’s a versatile ingredient in the traditional pantry. Meatier than bacon, it contributes more flavor and has a richer texture, making it a popular partner for first-of-the-year greens and peas.

IF YOU’VE EVER BEEN FORTUNATE ENOUGH TO experience one of Alabama’s Mobile Bay jubilees, you’ll understand exactly why Spanish explorers christened the body of water Bahía del Espíritu Santo. The rare natural phenomenon, when marine life swarms ashore for the taking, has a mystical, almost religious quality. On warm summer nights when conditions align, the shallow bay—its average depth is only ten feet—can experience a dramatic drop in oxygen levels. Coinciding with a predawn rising tide and gentle easterly wind, hypoxic water wells up and moves west, herding all sorts of marine life before it. Rendered nearly catatonic, shrimp, anchovies, rays, and flounder crowd along the shoreline; blue crabs cluster up the sides of dock pilings; and gasping eels poke their heads out of the water. They’re all searching for oxygen, and once word of their arrival spreads, locals descend with gigs, nets, and buckets in hand. Filling a freezer with an entire summer’s worth of seafood in mere minutes is certainly cause for celebration, thus the name, which dates to a 1912 report in Mobile’s Daily Register, though records of jubilees go back to the 1600s, when settlers first colonized the area. Sometimes a jubilee may be highly localized in a 100-yard-long stretch of the eastern shore; in rare years, one might extend fifteen miles from Daphne down to Mullet Point. It may occur a dozen times from June to September, or only once. But as quickly as it happens, the jubilee ends, departing with the tide—and leaving a few lucky folks who heeded the call with laundry baskets full of the bay’s bounty.

JUKE JOINTS AROSE AS THE AFRICAN American nightclubs of the rural South, and they’re where the blues was born. Lightnin’ Hopkins, Robert Johnson, and B. B. King all cut their teeth in juke joints with names like back-roads poetry: Marion’s Place, House of Joy, Simmons Fish Camp, Po’ Monkey’s.

In 1928, Justus P. Seeburg, a builder of player pianos, combined a loudspeaker with a coin-operated phonograph that played eight selections. Within a dozen years, three-quarters of all records produced in the United States wound up in such “automated music vending devices,” and every juke joint had to have one. That’s how we got jukeboxes.

JULEPS ARE A CLASS OF LAVISHLY ICED ADULT beverages associated with the Old South of verandas and the New South of the Kentucky Derby.

The julep’s heritage is long and widely traveled. The word comes from the Persian word for rosewater, gulab, which the French called julep and which migrated as such into English. It evolved in America to describe a morning medicinal drink, made of spirit (often brandy) infused with botanicals (often mint) to keep away diseases borne on fogs and miasmas.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, ice inundated the South, shipped to icehouses aboard a growing fleet of insulated ships filled with pond ice cut during Northern winters. Soon ice made a lasting and fortuitous acquaintance with the julep. The first such drinks were often called “hailstorms” after the crushed, hailstone-like ice that adorned the inside and (often) outside of julep cups.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, the julep was the most popular drink in America. Then it fell from fashion, most likely owing to the labor involved. While juleps are experiencing a revival in some of the South’s better bars, today they are chiefly associated with the annual running of the horses at Churchill Downs. Some claim that more juleps are served in that place on that day than in the rest of the year in the rest of the South combined.

SCHOOLCHILDREN LEARN THAT ABRAHAM Lincoln “freed the slaves” in 1862 by signing the Emancipation Proclamation, which stipulated that all enslaved people in rebelling Confederate states would gain their freedom on January 1, 1863. But war combatants don’t take kindly to their enemies’ decrees, so the measure worked only where Union troops were on hand to enforce it. Fearing that situation, huge numbers of slaveholders marched their slaves deep into Texas, where slavery persisted even after Robert E. Lee surrendered. Then, on June 19, 1865, Union general Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston with an occupying army and announced, “All slaves are free.” The following year, African Americans marked the occasion with the first Juneteenth, singing songs and playing games. Celebrations, often featuring barbecue, baseball, and red soda, grew in size and magnitude until Jim Crow laws systematically deprived black Texans of anything that resembled freedom. But those who moved north carried the anniversary with them. In the late 1960s, it emerged as a national holiday, superseding smaller observances in places that freedom reached sooner. As the Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates has written, “By choosing to celebrate the last place in the South that freedom touched, we remember the shining promise of emancipation, along with the bloody path America took by delaying it.”

FOUR COUNTRIES AND 291 CHAPTERS. A who’s who roster of illustrious alumni—including Ann Bedsole, the first woman to serve in the Alabama State Senate, former First Ladies Barbara Bush and Laura Bush, and Eudora Welty—and a tradition of civic leadership dating back to 1901. The all-female Junior League, officially called the Association of Junior Leagues International, originated in New York City, to address issues of poverty and affordable housing. Soon its scope broadened, both geographically and philosophically, and Junior League members began creating community cookbooks (first popularized in the 1800s) to fund their various projects. The Dallas chapter claims the oldest version, published around 1920, followed by a collection from Augusta, Georgia, around 1940. From there, it’s impossible to count the number of spiral-bound cookbooks produced by Junior League members. Popular Southern titles include Stop and Smell the Rosemary: Recipes and Traditions to Remember (Houston), Southern Sideboards (Jackson, Mississippi), and With Our Compliments (Charlottesville, Virginia). But the undisputed sales leader is Charleston Receipts. First printed in 1950, it is the League’s longest-running and most-purchased title, having netted $1 million and counting for local charities.