TED ZUBER didn’t see the Chinese sniper homing in on his position. The RCR private was situated in a bunker that had once been a UN observation post called Ronson. It overlooked no-man’s-land in an area known as the Hook, so named because it jutted hook-like into the Sami-ch’on valley. This forward outpost had been so badly shelled during the months UN troops had used it, it had caved in and been abandoned by regular riflemen. The damage meant that Zuber’s field of view was limited to a few hundred yards. He had a blind spot on his left.

Zuber’s partner, Pte. Al Craig, sat a few hundred yards to Zuber’s left and a little lower, covering Zuber’s blind spot. He too was dug in. He had spotted the Chinese sniper creeping toward Zuber’s position, but couldn’t get a clear shot at him.

Craig and Zuber had been paired in sniper training when their Royal Canadian Regiment moved off Hill 355 in early November, 1952. Their instructor, Sgt. MacPherson, was a veteran sniper from the Canadian campaign to liberate Holland in 1944–45. He had trained them with sniper scopes on Lee-Enfield, single-shot, boltaction rifles. Their RCR colonel had told them they would be useless to the battalion unless they could “put six out of ten rounds into a two-cent book of matches at 500 yards.” Zuber and Craig had each hit the mark with at least eight shots. They had gone on to learn camouflaging, sight optics and stalking.

Now Pte. Zuber was being stalked and didn’t know it.

The two RCR marksmen had rigged a temporary field phone linking their two positions. Finally, Craig wondered what was taking Zuber so long to react. He rang his partner. “Ted, you see the sonofabitch?”

“Where?” answered a startled Zuber.

“Why are you letting him move up on you like that?”

“What’re you talking about?” Zuber said. He had seen another Chinese soldier jumping up and down in a trench farther away, but Zuber figured that soldier had probably been ordered to draw fire in order to expose the Canadian position to Chinese sniper fire. Still, Zuber was oblivious to the sniper in his blind spot. “I can’t see him at all,” he admitted to Craig.

“Let me tell you exactly where he is,” Craig said.

As trainees, Zuber and Craig had not only taken the course together, but also MacPherson, their instructor, had told them “to eat, sleep and shit together . . . so you’ll find out how each of you thinks, so you know what not to expect from each other.” So, although he couldn’t see a thing in front of his spot on Ronson, Zuber trusted Craig’s word without even thinking.

“I think he’s taking up a firing position . . . about 125 yards to your front. A bit to the left. Not quite 11 o’clock.”

Zuber trained his Lyman-Alaskan sight toward the spot.

“I’m going to shoot the guy in the trench.”

They both knew that the Chinese soldier leaping up and down in the distant trench would only be momentarily visible, so Craig wasn’t likely to hit him. Zuber realized what Craig was up to and prepared himself.

“Ready?” Craig said.

“Go!”

Craig fired at the man in the distant trench. The Chinese sniper lifted his head to see where the unexpected shot had come from, and in that instant Zuber found the sniper in his sights and killed him with one shot. It was one of five kills Pte. Zuber would make as a sniper during three months on the Hook position.

Far from being a pathological killer, Pte. Ted Zuber was merely a soldier who had adapted to soldiering in what would turn out to be another year of attrition along the front lines. Had he not joined up to go to Korea, Zuber might have followed up his apprenticeship in Kingston, Ontario, with a career in commercial photography. Or he might have gone home to Montreal to pursue his hobby as a sketch artist. As it was, he applied his photographic knowledge to gunsights and scopes, and his artistic ability to sketching field drawings of terrain and Chinese army positions for the intelligence section of his regiment. He was riding shotgun for the battalion, and the job seemed to reflect his aptitudes and personality.

“The army made us polish the insole of our boots . . . press our boot laces . . . polish the backside of our brass . . . starch all of our uniforms,” Zuber said. “And while I was comfortable with the need for military discipline . . . I didn’t want any part of it. I somehow grasped that the sniper section was the only place in the infantry where I could work as an individual.”

No one soldier working alone was going to win this war. Ted Zuber knew that. By now, most knew that this war was not winnable. Nor did it seem negotiable. Since July 1951, representatives of opposing military commanders had been meeting off and on to reach an armistice. While the leading figures involved never suggested they would abandon the talks in favour of military escalation, neither did they seem ready to surrender any part of the battlefield to the other side. The pattern was clear to troops of all armies in Korea. Defensive front lines would remain unchanged. They would be dug deeper. The war was deadlocked.

Mao Tse-tung had ordered his officers to engage the Americans “in positional warfare, where bloody fights were waged with little exchange of land.” There would be no victory, just endless skirmishes between groups of soldiers in trenches and out in no-man’s-land, “where lessons for war from 1917 were more applicable than those from 1944.”

By the time UN Command had consolidated its forward position along the imaginary Jamestown Line in the fall of 1951, the commanders of the Commonwealth Division sent patrols into no-man’s-land every night. Unlike the South Korean ROK Army patrols, whose general philosophy was to advance, find the enemy and fight it out, each Canadian patrol had a different strength and a different mandate.

A fighting patrol, usually platoon-size (about thirty men), would attack an outpost, capture (or “snatch”) a prisoner or create a diversion to keep opposing troops off balance. An ambush patrol of fifteen to thirty men would set a trap in an area through which Chinese patrols were sure to operate. A recce patrol included an officer or sergeant and three or four riflemen, and their task was to retrieve information on routes, enemy defences or its movement patterns; they were sometimes the bait for a larger ambush patrol. An escort patrol worked with engineers or pioneers while they carried out their tasks, and a standing patrol worked out in front of a company position to give early warning of any Chinese activity in the region.

In this static war, information was power. On the surface, at least, patrolling was designed to get information by whatever means— spying on Chinese soldiers, capturing them and, if need be, engaging them. Most platoon commanders realized patrolling was also designed to keep up their soldiers’ fighting pitch during the lulls in ground warfare. No one who was responsible for the safe return of soldiers from a night patrol dared let his men fall into a false sense of security or, as PPCLI platoon commander Bob Peacock noted, “No patrol is ever routine, unless you want it to be your last.”

Peacock’s No. 6 Platoon set out one night in the fall of 1952 to establish a forward patrol base on Bunker Hill, a small hill some 400 yards in front and to the right of Hill 355. The only protection that Bunker Hill offered were the remnants of fire positions and shallow trenches. The platoon was assisted by a Forward Observation Officer, stretcher-bearers and the battle adjutant, Maj. R. F. Bruce, acting as patrol master that night. The patrol went like clockwork. Peacock’s group arrived at Bunker Hill a little after nightfall. Canadian fighting patrols passed through en route to their appointed rounds, and things fell silent for about an hour.

“Suddenly, heavy fighting broke out close by in front of an American forward position,” Peacock wrote. “The Chinese had launched a silent attack without any artillery support, probing the gap between the Americans and ourselves . . . [Then] we were raked by heavy machine-gun fire which our American neighbours had brought into action . . . Luckily we were fairly well protected in our shallow slit trenches. Maj. Bruce narrowly missed being a casualty as he was in the open taking care of personal matters when the machine-gun fire hit our position. He said later the experience had given him a different view of routine patrolling.”

John Tomlinson was rushed to Korea as a reinforcement for the 1st Battalion RCR in the summer of 1951. As a nineteen-year-old private, Tomlinson felt he had plenty of attributes for the job. He had joined the regular army in 1950, taken paratroop training and become a signaller in a demonstration platoon that was used to train officers. In fact, at Camp Borden’s School of Infantry, he became part of a movie cast shooting a warfare training film, “I think it was called ‘Infantry Platoon in the Attack.’

“There were three or four cameras and a director on a vehicle beside us,” Tomlinson said. “We start off walking down a road . . . come under fire and go to ground. The lead section comes up into firing position and engages the enemy. Then the section commander discovers it’s a machine-gun nest, so word goes back . . . The platoon commander gives his orders . . . So we’d do a right flanking attack, engage the enemy in a fire fight. The two rifle sections would sweep through and capture the position . . .

“Except in war it doesn’t work like that. There’s a bit more confusion. It isn’t daylight. And when the platoon commander stands up, he gets a bullet between the eyes. And there’s no guarantee when you’ve finished, the forty men you started out with will still be there at the end.”

Few of his patrols at the front in Korea went according to the script either. During a company patrol across the Sami-ch’on valley toward Hill 166, Pte. Tomlinson was part of the platoon headquarters, fifty yards behind a fighting patrol. As it climbed the forward slope of the Chinese-held hill, the leading patrol became plainly visible, even in the dead of night. In the resulting exchange of fire, the vanguard sustained numerous casualties and the entire company had to make a hasty withdrawal. Tomlinson hasn’t forgotten the emotional and physical exhaustion of that night:

“I never wet my pants in fear, but there was a lot of adrenaline flowing . . . Out in the middle of that valley, no-man’s-land doesn’t belong to anybody. And when you suddenly come under fire, I don’t care if you’re in a parking lot in downtown Toronto with no lights and somebody’s firing at you . . . it’s a feeling of high excitement.”

Patrolling, or the prospect of patrolling, brought out the best and worst among infantrymen when their turn came. Not unlike nervous military aircrew, who traditionally urinated on the tail wheel before taking off on a combat mission, anxious troops could experience everything from sweaty palms to hives to vomiting before a patrol. Sometimes the personal upheaval was psychological, such as the day John Tomlinson and “C” Company of the RCR were rotated back into the front lines in March 1952. Tomlinson was paired with a bunker mate who had never patrolled before. He suddenly found the recruit polishing a .303 bullet.

“What’re you doing?” Tomlinson asked innocently.

The man kept rubbing.

“Why are you polishing a rifle bullet?”

“I’m going to shoot myself . . .”

Tomlinson thought the soldier was kidding.

“Promise you won’t tell?” the man said.

“Sure,” Tomlinson laughed, “if you give me your beer ration.” And he sat down and began undoing his bootlaces.

Moments later, the recruit loaded his rifle and fired. The breach of the rifle was right beside Tomlinson’s ear and he jumped back in astonishment. The frightened man had blown a hole in his foot.

Because most patrols were mounted at night, fear of the dark was common. Jim “Scotty” Martin, an RCR platoon commander with the 1st Battalion, had a corporal whose childhood fear of darkness lingered into his tour of duty in Korea. It was a detail that Martin picked up along the way and jotted down in a notebook he kept on the men in his platoon. Martin also noted that Cpl. Vic Dingle “was a bit dogmatic . . . had pretty strong opinions . . . that the troops called him ‘Crow’ because of his dark complexion,” and most important, “that he was a good section commander.” On May 23, 1952, he proved it.

Lt. Martin led a fighting patrol with five additional pioneers that night. The objective was to establish a firm base on the far side of the Sami-ch’on valley that would allow the pioneers to set booby traps around several Chinese mortar positions on Hill 156. Before he could establish the firm base, Martin’s patrol ran into a Chinese patrol. In an instant, it seemed, the night lit up with machine-gun fire, rifle fire and grenade explosions.

“We go to ground,” Martin said. “It’s obvious I can’t set up a firm base, so we draw off the hill. But as the fire opens up, we’re all diving for cover and I get hit in the leg.”

Because of the adrenaline pumping through him, at first Martin didn’t realize how serious the wound was. He had enough of his wits about him that he avoided shooting his pistol in the dark, and instead heaved fragmentation and phosphorus grenades in the vicinity of the Chinese patrol. What was left of Martin’s patrol gathered at the base of the hill. One soldier was dead. Three others were wounded. The pioneer platoon had already begun to retreat. The patrol got word to pull back, and then Martin realized “a third of my calf muscle is sticking out the side of my leg” and he could barely walk.

That’s when Vic Dingle, Martin’s senior corporal, rose to the occasion. He suddenly sensed that his platoon commander was relying on him. At that moment—fear of the dark or not—survival of the platoon depended on him. Dingle quickly organized the retreat. Each section was to act as a firm base for the other as it withdrew. It took the rest of the night, but with Martin hanging off his shoulder, Dingle got the remainder of the patrol home to its company position. At dawn, as Martin was loaded onto an evacuation helicopter bound for a MASH unit, he learned that the pioneers who had been with him on the patrol took a short cut and walked right into a minefield; five more were wounded. It was a patrol “that just didn’t click.” However, an alert and apparently fearless Cpl. Dingle probably saved it from being a disaster.

If patrolling itself was stressful, patrolling on a winter’s night added to the discomfort. By this time in the war, most infantrymen had thrown away the Department of National Defence handbook on Korea with its claim that winters in South Korea were “a chilly version of British Columbia’s.” In the middle of Korea, just above the 38th parallel, the cold could be Arctic and the wind-blown snow could verge on white-out. Moreover, army-issue parkas were not an asset because the swishing noise of nylon rubbing on nylon was nearly as loud as a man’s voice in an open field.

Cpl. Jack Noble won’t forget his turn on patrol one January night. Normally a machine-gunner with No. 11 Platoon of the RCR’s “D” Company, Noble went out this night to back up a fighting patrol sent out to bring back a Chinese prisoner. As the leading section of the patrol reached the Chinese side of the valley, an RCR soldier stepped on a Chinese mine. The snatch attempt was immediately called off.

Through much of the rest of the night, the RCR fighting patrol tried to draw the fire of a pursuing Chinese patrol, while Noble and a couple of medics brought back the wounded. They made litters with their rifles and carried the men in slings. The temperature dropped so quickly that night, Noble’s feet went numb with the cold. He took off his boots and walked in his sock feet so that at least the friction of his feet rubbing on the frozen ground might revive the feeling in his feet. The medical group got back safely, but the soldier had lost a foot to the Chinese mine. Cpl. Noble had nearly lost both feet to the cold.

The troubles hadn’t ended for that night’s mission. When the members of the fighting patrol finally reached the gap in the UN minefield to re-enter the RCR company position, they were stopped in the darkness.

“Halt,” shouted one of two Canadian sentries on duty at the gap.

The fighting patrol halted as ordered. Now an irreversible sequence of events had begun, and its successful outcome depended on everyone following procedure to the letter.

“Advance one and be recognized,” continued the sentry.

That was the signal for a person in the dark to take one more step forward and announce the first half of a double-barrelled password, such as “Blue Bonnet” or “Betty Grable” or “Nuts and Bolts.” The patrol leader advanced a step, but there he hesitated. He had forgotten the night’s password.

By rights, the sentries could now open fire. They would not be held responsible. It wouldn’t be the first time a Chinese patrol had tried to penetrate the UN front line this way. Some, they said, could even speak perfect English. The safeties came off the sentries’ weapons. They also hesitated.

In the nick of time, someone else in the RCR patrol blurted out the right first password.

The sentries cursed loudly, more to relieve the tension than to condemn the patrol. Then there was nervous laughter all round and a retreat to the bunkers for a toddy of rum.

When the Korean War began, a soldier’s most trusted tool in the field was his firearm, whether a Lee-Enfield rifle, a Bren gun or, if he traded liquor for it, an American .30-calibre carbine. However, by the time negotiators began talking peace and the United Nations armies reached the vicinity of the 38th parallel, the soldier’s most trusted tool was his shovel; instead of surviving on the hills at the front line, a soldier was expected to survive in them.

When the battlefield was constantly shifting, soldiers dug slit trenches for command posts, ammunition pits and latrines. Most trenches were temporary. When the fighting reached a stalemate at the Jamestown Line, they dug trenches and pits and latrines all over again. But they also dug holes to live in. These cubbyholes were either adjacent to the fighting positions or on the reverse side of the hill being defended. They were permanent. Indeed, the progress of the war (and the peace) was soon reflected in the depth and permanence of the soldier’s living quarters in the front lines.

Bunkers began life as slit trenches. Open to the great outdoors, these three-to-five-foot deep trenches allowed in rain or searing sunshine during the summer, or snow and freezing cold during the winter. Excavation of a trench ended when the excavator hit rock. That’s when sandbags, piled on top of one another, gave a trench the desired overall depth and protection. However, the real spur to renovate a trench resulted from another natural phenomenon.

“Open slits made irresistible traps for every wandering snake or field mouse and insects that leaped, wriggled or crawled,” L/Cpl. John Dalrymple wrote. “In the evening, after evicting the more obvious of intruders, [a soldier] would settle down to vainly search for dreams on a rustling palate of rice straw, assorted spiders, homeless beetles, five-inch praying mantises and displaced but industrious ants. One night of this would make an ardent convert for the Home Improvement League.”

A roof was the earliest addition to the evolving bunker. Tree limbs or scavenged timbers provided the rafters and a groundsheet pegged at the corners offered a temporary water-resistant ceiling. The flotsam and jetsam of war—ration crates and ammunition boxes—became furnishings. Sometimes a sleeping ledge could be cut into the side of the trench with rice straw for warmth. In winter, an old tea kettle loaded with glowing charcoal made a small furnace that threw a bit of heat without any tell-tale smoke or glow to reveal the position.

When a visit on the hillside turned into a long-term stay, the roofed-in slit trench could be ripped apart and expanded into a full-sized bunker or “hootchie.” Occupants would dig back deep into the hillside and roof their bunker with heavy logs. Above that, soldiers wove together a cushion of branches, twigs and straw mats, topped by a rubber groundsheet, loosely packed earth and greenery to camouflage the location. Inside, three or four bunker mates built an earthen ledge for dry sleeping, a couple of openings for standing guard, a cupboard carved into one wall for ammunition and rations and a fireplace at one end with a concealed chimney made of bazooka bomb cartons.

“We used to make our own beds with machine-gun belts,” Bud Doucette said. Of his 127 days in action with the RCR in Korea, L/Cpl. Doucette spent most of them defending one hill or another as a machine-gunner. To make daytime sleeping hours more comfortable, “We’d weave the used machine-gun belts together, hang them up and sleep on them,” much like a hammock.

“We were a long way from civilization,” Charlie LeBlanc recalled. A Cape Breton farmer, Cpl. LeBlanc arrived in Korea as a section leader in Able Company of the R22eR. While manning Hill 355, LeBlanc and his bunker mate Ken Snowden converted wooden ammunition boxes to tongue-and-groove flooring in their bunker. That impressed his colonel, but not the sign he’d posted over his bunker. “It said ‘Charlie’s Shortime Inn.’ He told me to take it down.”

Aside from the aforementioned insects, the only living creatures that enjoyed life in bunkers were the rats. Despite the use of rat poison, rat traps and general hygiene in the trenches and bunkers, rats thrived. They chewed everything from leather picture frames to gun belts. They crept into sleeping blankets. They dug themselves into every nook. Not only were they unsanitary, they bore something lethal—haemorrhagic fever, or Songo fever. The disease originated in mites living on the rats; when the mites bit a soldier on the neck or wrists, his blood would begin clotting, which clogged his liver, causing him to die of his own body poisons.

“There was no cure for it,”medic Cosmo Kapitaniuk said. As far as he knew, the Japanese had encountered it during their Amur River campaign against the Russians in the 1930s. It was generally understood that eight men in ten died when infected by the disease. “Whenever a guy showed symptoms, they evacuated him immediately by helicopter . . . There was this secret American lab south of the 8055th MASH unit . . . It was off limits even to us.”

“I thought I had leprosy or something,” said Don Flieger, a Service Corps corporal who worked at Kimpo Airfield near Seoul. For amusement (and safety) at night, Flieger and his buddies would sit on the edge of the runway, spot rats with flashlights and shoot them with their 9-mm pistols. In February 1952 he developed a rash that turned into blisters. When he arrived at the special American MASH unit, “I had a temperature of 104 . . . The blisters had broken and started to bleed. I was terrified.” If it weren’t for the eight complete blood transfusions Flieger underwent over the next two months en route home, he probably wouldn’t have lived.

In response to the threat of insect bites and diseases, the brigade began equipping its front-line soldiers “with paludrine pills, antilouse powder, anti-flying insect aerosol bombs and anti-mite oil—the latter messy for it must be smeared on pants cuffs, shirttails and neck bands.”

The “Chino bunkers,” as some front-line infantrymen referred to them, had two other nemeses. Monsoon rains, which sometimes lasted for weeks, placed additional weight on bunker roofs and caused them to collapse, trapping their occupants. PPCLI platoon commander Bob Peacock pointed out that “in August 1952, we lost eleven of fourteen bunkers in a single day . . . A minimum of ten inches of rain fell in a twelve-hour period . . . The roof of our platoon HQ bunker suddenly dropped on the four of us, burying us in sandbags, logs, mud and other debris. We were fortunate to get out alive with nothing more than cuts, bruises and the loss of some personal equipment and clothing.”

The bunker’s other mortal enemy was the Chinese army’s guns. A combination of their Russian-designed SU76 high-velocity assault guns, their 152-mm howitzers, their 122-mm artillery and their mortars could deliver relentless fire across no-man’s-land at any time. Because the United Nations’ air forces controlled the airspace over the front, the Chinese dug their battery positions deep into hillsides or tunnels so that they could fire with maximum protection. A Chinese artillery and mortar barrage signalled several things. First, it generally meant a new gun unit had arrived at the front and was “registering” or homing in on a UN target. Second, it often forewarned of an imminent ground attack. In either case, if the Chinese artillery and mortars chose a “time-on-target” barrage, in which shells from various positions all landed on the target at the same time, the explosions often made short work of the UN’s bunkers and command posts, no matter how well constructed and fortified they might be.

Where fifty Chinese shells in a day were notable in the autumn of 1951, the average had reached 2,500 in the Canadian area a year later. In fact, the Chinese inflicted their heaviest bombardments between mid-1952 and mid-1953, consequently, “the heaviest casualties of the war were incurred in the last year of the conflict.” The proportion of killed to wounded—normally one-to-ten—in this period was one-to-two.

Correspondents interviewed front-line troops about life under fire. Some visited their bunkers between barrages. They all tried to put phrases such as “shelling,” “under artillery fire” and “bombardment” into perspective. “The soldier sits in his dugout or his slit trench and is shelled. What happens?” asked Canadian Press correspondent Bill Boss. “The whistle-whine of the approaching missile sends an involuntary sharp tug of destruction on his heart . . . Lying in that hole, or caught out in the open on patrol . . . with messengers of death and injury raking to and fro about him, now close, now far, now sprinkling him with dirt, now spinning jagged bits of shrapnel whirring through the air, he counts his chances. Life, so real right now, could finish in a flash.”

On September 1, 1952, “C” Company of the RCR sustained four casualties due to artillery fire. The following day, “A” Company lost nine men as a result of a salvo of mortars that also knocked out a Lord Strathcona’s tank, injuring its crew of four. Three days later, Lt. Cyril Harriott, who had struggled for months to obtain a posting to Korea, reported to Able Company; within minutes of his arrival in the front lines, Harriott was killed when an incoming shell exploded at his position.

“The first night I was on the hills in a bunker I was shit scared,” Ed Ryan said. After joining the military in 1951, Ryan found himself at Currie Barracks in Calgary, where the Princess Patricias discovered his talents as a hockey player. He figured he’d sit out the war on a players’ bench at the Calgary Corral, but as the need for front-line replacements increased, Pte. Ryan ended up on a draft to Korea to reinforce Baker Company of the PPCLI.

“I always figured I should come back with a V.C.,” Ryan mused. “But then one night it was raining and mortars were coming in . . . [Normally, they] would have hit the ground and the shrapnel would have just cut us to pieces. But the mortars just embedded into the soft soil and everything was blowing up around us. I started calling for my mother: ‘I want to come home!’ I was so scared.”

Dave Baty was a PPCLI reinforcement too. On a day late in May 1952, as his Able Company moved forward from a reserve position toward the front lines, “the Chinese must have spotted us. And their shelling was quite accurate . . . It was their 122-mm artillery.

“The first thing they hit was a fuel dump,” Baty said. “When they saw they’d hit something—all the flames and that—they really poured it on . . . I got hit trying to find cover . . . Shrapnel got me on the back and legs and arms. But I don’t think I’d be here if the shells weren’t hitting rice paddies. If they’d landed on the road, I’d be a dead man.”

There were amusing near misses too. When “B” Company of the RCR rotated onto Hill 159, No. 6 Platoon built an outhouse, complete with sandbag fortifications, right in the middle of the platoon area near the hilltop. On this particular day, during a break in the action, Pte. Art Browne made his way to the outhouse. His friend, Cpl. Russ Cormier, watched in horror as a Chinese self-propelled shell crashed into the outhouse and exploded deep in the outhouse pit. In the seconds before the shell hit, Browne had stood up and pulled up his boxers. When the smoke and dust cleared, Cormier saw Browne standing uninjured but with his pants down around his ankles. He was shouting: “Missed me! Missed me, the buggers!”

Even tank crews of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse felt vulnerable to the Chinese guns. During the Second World War, Phil Daniel was with the 1st Hussars armoured regiment, and in Europe “if you were fired at three times, you would move . . . In Korea, we used to get fifty shells every day at noon . . . but up in those hills you couldn’t move. Where could you go? You were dug in. You were trapped. You sat and took it.”

Just after 9 o’clock on August 20, 1952, Sgt. Daniel’s tank was hit by a Chinese shell. All five crewmen were in the tank at the time. With the explosion, “everything turned red,” Daniel said. “I was knocked out by the shrapnel. The driver [Tpr. L. G.] Neufield was killed. But we were in such an awkward spot, we had to wait until noon before they could get ambulances in to us.”

When the Petit brothers—Claude and Norris—got to Wainwright’s advanced training area with the PPCLI in the spring of 1952, they experienced forced marches, bivouacking in the wilderness and war games. In the middle of one exercise, soldiers in small circling aircraft “dropped bags of salt on us from the plane” to simulate mortars and shells falling on troops in battle. Neither of the Metis brothers from Duck Lake, Saskatchewan, seemed fazed by salt bags falling from the sky. But the real thing was different.

One afternoon, shortly after “C” Company of the Princess Patricias moved into a counterattack position behind the Hook in November 1952, Pte. Claude Petit was manning one end of a stretcher full of supplies for members of his No. 8 Platoon. Re-supplying up and down the reverse slopes went on during daylight hours. So did Chinese shelling.

“All of a sudden the shit hit the fan,” Petit said. “Mortars were coming in and they kept coming up the hill toward us.”

The other man holding the stretcher was hit between the shoulder blades in his back. He passed out on the spot. Petit and a nearby medic grabbed the man and pulled him into a bunker, where they bandaged him and administered morphine.

“What the hell?” said Petit suddenly. He was looking down at his bloodied hands.

“You’re hit someplace,” the medic said. And he cut open Petit’s coat to reveal wounds on his shoulders. What the medic also found under the private’s coat was a recently arrived experimental bulletproof vest. It, instead of Petit’s stomach, had been cut to pieces by flying shrapnel.

“They weighed about sixty pounds,” Petit said. “But I never took that bastard off again, while I was up there.”

One of Claude Petit’s fellow Patricias, Butch MacFarlane, considers himself even more fortunate. One midday, MacFarlane, a Bren gunner with “B” Company, sat with several other members of his No. 5 Platoon near platoon headquarters behind the Hook. They had paused among the stacks of barbed wire and piles of iron stakes (used to string wire in front of no-man’s-land) to eat their C-Rations.

“All of a sudden there was this awful whack, just like somebody smacked an anvil with a maul hammer,” MacFarlane said. “We all scattered. Then, when nothing happened, like a near-sighted bear, we all came back looking to see what had happened . . . Sticking out from among all these iron pegs was the tail fin of a Chinese mortar. They didn’t pull the pin out. It didn’t explode . . . The shrapnel from the iron pegs alone would have ripped the hell out of all of us.”

As the static war in Korea evolved, so did tactics. Joe York, a corporal in the RCR assault pioneer platoon, remembers taking a course using huge searchlights, several kilometres behind the lines, to bounce beams of light off the clouds at targets on the Chinese side of the valley. The resulting “artificial moonlight,” while helping UN gunners pinpoint Chinese positions, also unexpectedly revealed UN night patrols. One platoon commander described the explosion of light in no-man’s-land like suddenly “being centre stage at Radio City Music Hall in New York.”

In the earliest days of the war, most Canadian soldiers considered their British tin-hat helmets clumsy and useless. Instead, they used toques and balaclavas. In Korean trench warfare, new bulletproof vests, like the one that saved Claude Petit’s life, and a strong, snug-fitting helmet were becoming regular infantry apparel. In fact, during Operation Trojan, Commonwealth troops were given American helmets as part of a deception to give Chinese spotters the impression that US units had moved onto Hill 355. In addition, UN troops were told to wear shirt sleeves down and buttoned. Signallers were to use American radio procedures, and troops were to use mostly American weapons. UN Command hoped the deception would tempt the Chinese into probing the new lines, thus increasing the potential for snatching Chinese troops as prisoners. The strategy worked until Canadian gunners fired their Vickers medium machine guns. The sound was easily recognized by the Chinese; the next morning Chinese loudspeakers across the valley were heard “welcoming Canadians” to the front.

Earl Simovitch and his combat engineers group discovered another aspect of the static war, “when they brought in a prisoner [who] told us they were digging a tunnel under our lines.” Pte. Simovitch had grown up in Winnipeg before the war, but moved to Minneapolis to become an architect. As a foreign student working in the US, he became eligible for the draft. He dutifully reported and wound up in Korea in 1952 as a camouflage and demolition specialist with the 65th Engineer Combat Battalion. The Americans were on hills adjacent to the Commonwealth Division in an area they called the Iron Triangle.

“We found out the Chinese had dug a tunnel maybe a couple of thousand yards [under no-man’s-land],” Simovitch said. “The Turks were near that section and they could hear the digging but didn’t know what the hell it was.

“They found an air vent on a shaft that may have gone down hundreds of feet. It was concealed by whatever shrubbery was left . . . I got together composition C and napalm in a large canister, but when I got to the front lines I started puking. I had been in a confined space preparing these demolitions. My head was pounding . . .

“The patrol went up, dropped the explosives down the vent. There was a thirty second delay. Then I heard this massive rumble. It seemed the whole top of the hill lifted,” effectively collapsing whatever tunnels lay underground. Simovitch received a Bronze Star (rare for a Canadian in the US military) for his service in Korea, but the memory of the destruction and life lost in those sorts of actions stayed with him.

By the autumn of 1952, the monsoon rains that had flooded many UN Command bunkers and washed away the brigade’s Teal Bridge across the Imjin, had ceased. Rebuilding was going on. Reinforcements were filtering into front-line positions, although most Canadian infantry platoons were operating understrength. Increased Chinese shelling suggested that an offensive was brewing. Consequently, the officers at various company command posts began sending out more fighting patrols, ambush patrols, recce patrols and snatch patrols, to bring back prisoners with information. It was common knowledge that “the prize for a Chinese prisoner was a week’s R & R in Tokyo.”

Four RCR troops went out on a lay-up patrol or snatch in early September. Signaller George Mannion, wireless operator Don Moodie, Cpl. Karl Fowler and patrol leader Lt. Russ Gardner crossed no-man’s-land to the Chinese-held Hill 227. They spent nearly sixty hours behind Chinese lines reconnoitring a kitchen area where about twenty soldiers were camped.

“It was the scariest thing of my life,” said Pte. Mannion, who packed around the fifty-pound radio set during the mission. “For two days and three nights we hid in the grass watching these Chinese . . . Some guys are gung-ho. I’m not. I was glad the lieutenant didn’t decide to grab a guy then . . . All I could think of was ‘Christ, I hope we’ve got the right password when we get back.’”

A few nights later, Gardner and Fowler led a larger snatch patrol back to the same area. They found a Chinese telephone wire near the kitchen and broke it. It wasn’t long before a Chinese soldier came looking for the break in the line, whereupon the RCR patrol seized him and brought him back alive. According to fellow patrolmen, “It was the oldest trick in the book,” but as important, it netted Gardner the Military Cross and Fowler the Military Medal. Moreover, information gleaned from the prisoner confirmed a build-up of Chinese troops and munitions and a move in the direction of Hill 355.

Two other encounters early that fall flagged a significant Chinese build-up in front of the Canadians’ defensive positions. On September 27, Lt. Dan Loomis led a fighting patrol to Hill 227 to seek out Chinese positions and strength. The patrol suddenly found itself pinched between a machine gun on the hill and an ambush patrol in the rear. In the firefight that took place, seven of the patrol’s twenty-three soldiers were wounded, including Loomis, who took shrapnel from a Chinese grenade. He still managed to extricate his patrol by leading it “single file through an old minefield that had been laid during Operation Commando” the year before.

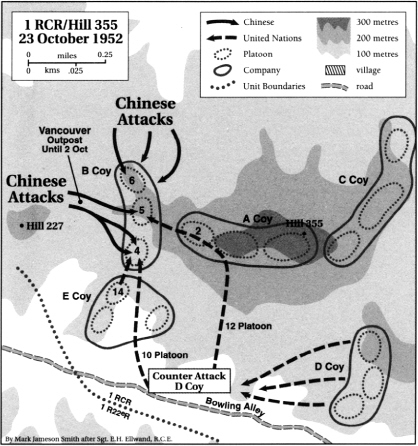

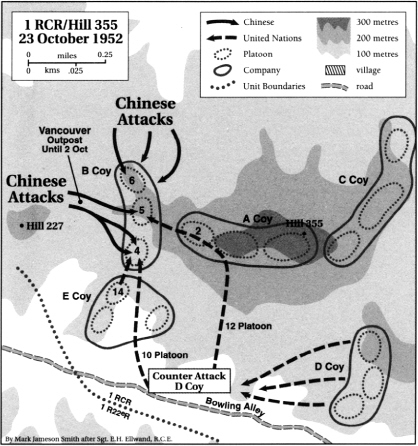

The second engagement on October 1 followed reports that a forward outpost—named Vancouver—had been overrun by Chinese forces. Lt. Andy King led a relief party to the outpost, where he found two men dead and the rest buried in the rubble of the command post. King organized the evacuation of the position while directing fire on an unexpectedly large Chinese force, which mysteriously vanished as quickly as it had appeared.

The anticipated assault against Hill 355 was about to materialize.

The summer and fall of 1952 had been eventful for Capt. Bob Mahar. He had come to Korea from the RCR’s base at Petawawa with the 1st Battalion. He’d gone onto Hill 355 with the regiment in August. By October he had moved from second-in-command to Charlie Company commander. After months of army rations, a food package had arrived from his wife. Mahar had always had access to eggs and flour, but not the final ingredient for his favourite dessert, lemon meringue pie. In his wife’s package was a box of powdered lemon pie filling.

“I was back at ‘B’ Echelon in the officers mess,” Mahar said. It was the afternoon of October 23, and he’d begun “to make lemon pies for me and anyone else who wanted them. And just as I got to take them out of the oven, the shit hit the fan up front.”

Chinese guns had been pounding the Canadian positions intermittently all month. Then, in late October, the frequency and focus of Chinese shelling changed dramatically. In one day, spotters counted about 1,600 shells hitting RCR positions, primarily on the saddle ridge between Hill 355 to the east and Hill 227 to the west. This small plateau, soon to be occupied by “B” Company of the RCR, was the same spot the Vandoos had defended so doggedly in November 1951.

“For four days they just laid the boots to us with every gun they had,” Capt. Herb Cloutier recalled. Back from his assignment earlier in the year with “B” Company (the so-called “Koje Commandos”), the RCR captain had recently organized “E” Company, an additional unit of riflemen. It occupied the draw immediately to the south of “B” Company as the bombardment continued. “I never saw anything like it. Hill 355 I think was [reduced to] 350 by the time they got finished shelling.”

When Platoon Nos. 4, 5 and 6, of Baker Company, went onto the saddle position, after dark on October 22, L/Cpl. George Griffiths remembered “a lot of the trenches and bunkers were caved in . . . The first night I was beside a machine-gun with a rifle. We were just shooting into the dark.”

Some of their fire found its mark. When the sun rose the next morning, Griffiths and his platoon mates spotted the bodies of several Chinese soldiers who were cut down trying to lay Bangalore torpedoes in the Canadian defensive wire. In the few bunkers that remained habitable, the thirty-four men of the three forward platoons tried to find cover underground and “lived that day on soda biscuits and jam.” The heavy shelling didn’t let up. That afternoon, the command post for No. 6 Platoon caved in under the pressure and the platoon commander, Lt. Russ Gardner, took shelter with Sgt. G. E. P. Enright of No. 5 Platoon, whose commander, Lt. John Clark, acted as runner between the platoon areas and the company headquarters. No. 5 Platoon rifleman, Cpl. Les Butt, left his two-man bunker when a shell explosion outside the bunker flipped him from his back to his stomach. He joined seven others from No. 6 Platoon in a more substantial shelter, where Cpl. R. R. McNulty, a Second World War veteran, kept up morale by telling jokes and making the men laugh. Instinctively, however, everyone knew an attack would come soon.

“That evening, I took a standing patrol down a little trail toward [former outpost called] Victoria,” Scotty Martin said. It was just a probe in front of the “E” Company position into no-man’s-land, “when the Chinese time-on-target barrage began. Fire was coming down on all three forward companies to the extent that the hills just disappeared. We ran back as fast as we could.”

Just after 6:30, with daylight gone and their guns registered on “B” Company’s position, the Chinese gunners opened up for ten full minutes, followed by fire left and right of the saddle area for another forty-five minutes.

From the neighbouring “E” Company position, platoon commander Dan Loomis was counting the orange flashes as Chinese shells and mortar bombs exploded. He stopped at 700, because “before it was over, visibility was less than an arm’s length due to the heavy pall of black fumes which also caused everyone’s eyes to water.” The Chinese had chosen to cut off “B” Company from the rest of the regiment.

At No. 5 Platoon position, rifleman George Griffiths was counting Chinese soldiers—not orange flashes. “My war was only on the two feet of ground I was standing on, and they were coming in [at a ratio of] ten to one.”

“I heard all this noise . . . Bugles blowing and yelling and screaming,” Jim McKinny said. As a lance bombardier with the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, he was stationed up Hill 355 at a forward observation post. To get a better look from his trench, he took out a set of donkey ears, a kind of periscope he used behind the protection of a parapet to register locations and angles for the artillery command post behind the lines. “I realized that the Chinese were overrunning the position.”

None of the RCR commanders understood how so large a Chinese assault force could appear so quickly on their doorstep. Despite all efforts to stop the onslaught—machine-gun fire, Bren-gun fire and grenade-throwing—the No. 5 Platoon position was losing ground quickly. In his immediate area, Lt. Gardner ordered a retreat up the hill toward the No. 2 Platoon position of “A” Company, but en route the group was hit by a mortar barrage. Gardner only survived by playing dead until the vanguard of Chinese troops had passed over him. Meanwhile, Lt. Clark and his group fought until their ammunition was expended; then he and his surviving group made their way toward “A” Company too.

When medic Cosmo Kapitaniuk reached the Advanced Dressing Station behind the RCR’s position, the wounded were already coming in, and he spent the night—some five trips in an ambulance— transporting RCR wounded to the American 8055th MASH unit. “Chest wounds, abdomen wounds, leg wounds . . . It’s a wonder some of those guys were still alive.”

Twice that evening, Capt. Cloutier tried to lead a signaller and several troops from “C” Company to reconnoitre the whereabouts of “B” Company survivors and to determine Chinese gains, “but there was so much dirt flying,” Cloutier said, “we were driven back to our bunkers.” About the same time, the No. 4 Platoon commander and “B” Company commander, Maj. E. L. Cohen, arrived at battalion headquarters behind the lines to report that their positions had been overrun. Any Canadians left in the “B” Company area had either been killed or taken prisoner.

The Canadian response wasn’t long in coming.

At the RCHA forward observation post, L/Bdr. Jim McKinny was both listening to wireless exchanges from the battlefield below and reporting troop movements. He heard the RCR commanding officer call for “D. T. fire” and took the grid reference where the fire should be aimed.

“That’s on top of you, sir,” McKinny radioed.

“Yes,” he answered. “And make it damn fast.”

McKinny’s relayed grid reference to bring fire down on Baker Company’s position had double significance for the young volunteer from Saskatchewan. He knew his cousin, L/Cpl. Gerald McKinney, an RCAMC medic, was in action with the 1st Battalion of the RCR. What L/Bdr. McKinny didn’t know was that in removing injured infantrymen from the battlefield, his cousin had been captured that night and spent the rest of the war in a Chinese POW camp in North Korea. L/Cpl. Griffiths, from No. 5 Platoon, also captured that night, was well on his way across no-man’s-land by the time the Canadian 25-pounder artillery pieces began firing into the saddle position below Hill 355.

“From 6 o’clock that night [October 23] until 6 the next morning we were firing,” Bob Bunting said. A bombardier at No. 2 Gun with “A” Battery, Bunting can recall few more hectic times in his artillery career. “All night, it was angle of sight, elevation and charge directions from the OP to the command post to the battery positions . . . The whole regiment joined in . . . The barrels of our guns were so bloody hot, the paint was just burning off them.”

“It sounded like bees buzzing over our heads,” said Herb Cloutier of the RCHA’s continuous firing. In fact, the Canadian shelling was so precise that it halted the Chinese advance and prevented any resupplying of the front-line Chinese storm troopers. At the height of the RCHA barrage, a South Korean monitoring the Chinese wireless communications heard a Chinese commander claim, “I am boxed in by artillery fire. I can’t get reinforcements forward.”

The temporary stalling of the Chinese offensive gave Canadian troops valuable time to regroup. A counterattack was organized from the “D” Company position to the rear of Hill 355. Capt. Bob Mahar received instructions for “C” Company’s role in the counterattack when a pioneer officer delivered a package containing a lemon meringue pie he’d left baking at the officers’ mess the afternoon before; his orders to relieve “D” Company were written on the bottom of the pie plate. Meanwhile, recce patrols led by Maj. Cohen and Lt. Clark into the “B” Company position from the east, and Capt. Cloutier from the south, helped retake the “B” Company area. By 3:30 in the morning of October 24, Hill 355 was back in Canadian hands. It was during this counterattack that some Canadian troops discovered what they had been up against that night.

“I jumped into one trench,” Cloutier recalled, “and there was a Chinaman with explosives strapped to his back. But before I could fire, his own people blew him up . . . One of them was wearing goggles . . . anti-gas goggles. That frightened us, because we suddenly realized they might be [attacking] with gas . . .

“And all night long, out in the dark, you could hear them dragging away the bodies of their dead . . . Next morning, we found all kinds of bandages and blood and bodies,” out in the former outpost positions. The Chinese had used the heavy bombardments not only to destroy Canadian defensive locations, but also to secretly move hundreds of troops forward into bunkers in the middle of no-man’s-land. That’s why the attack on “B” Company was so rapid and overwhelming. That’s why the casualties, sustained mostly by Baker Company, were so high—18 killed, 35 wounded and 14 taken prisoner. Spotters in helicopters the morning after the battle counted in excess of 600 Chinese bodies in the valley. UN Command estimated that about a hundred RCR troops had defended the base of Hill 355 against two Chinese battalions, or about 1,500 men.

For defence of Kowang-san, Military Crosses were awarded to Capt. Cloutier and Lt. Clark, while Sgt. Enright was awarded a Military Medal. The greatest praise was reserved for the Canadian artillerymen. Capt. D. S. Caldwell, the Forward Observation Officer with the RCHA, was also awarded a Military Cross. Soon after the battle, the RCR commander Lt.-Col. Peter Bingham presented the RCHA commander, Lt.-Col. Teddy Leslie, with the VRI (Victoria Regina Imperitrix) cipher, the RCR regimental crest, for display on their gun shields. There’s some disagreement whether the presentation was a jab for bringing RCHA shells down on Canadian positions, or as a badge of honour for the defence of Kowang-san.

“No question,” Herb Cloutier concluded. “Artillery saved our bacon. That’s all there is to it.”

On November 1, 1952, the Royal Canadian Regiment turned over Hill 355 to the 1st Royal Australian Regiment with the following notification:

“This is to certify that Kowang-san has been handed over slightly the worse for wear but otherwise defensible.”

The same day that Canadians turned back the Chinese at Kowangsan, Republican presidential candidate Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke to a partisan crowd of 5,000 during a whistle-stop in Detroit. He criticized the Truman administration for making the American public “wait and wait and wait” for peace. He promised, “I will go to Korea,” and in so doing bring about an end to the war. Two weeks later he trounced his Democratic opponent, Adlai Stevenson, 442 electoral votes to 89. By December 2, 1952, the president-elect arrived in Korea and listened to his generals’ aggressive plan to win the war militarily. Instead, Eisenhower would continue the Truman policy of seeking a negotiated solution.

In fact, the peace negotiations were still bogged down on voluntary repatriation of POWs and had regressed into “an institutionalized propaganda forum.” All the while, the symbolic searchlight illuminated the skies over Panmunjom as it had for a full year. Soldiers such as RCR platoon commander Bert Pinnington, himself wounded in a shelling on Hill 355 and petrified that the next one would kill him, watched “the searchlight all the time, beaming straight up in the air . . . Guys being killed week after week, month after month . . . And these donkeys are discussing peace.” It made Pinnington wonder, “Why are we here? What are we fighting for? I thought I’d be charging up hills and doing really dramatic things. But instead I was sitting in a hole . . . waiting.”

Pinnington had been one of 1,197 Canadian casualties in Korea to that point.

In the early-evening hours of New Year’s Day, 1953, RCR sniper Ted Zuber had come in from a successful daytime mission. He had taken out a Chinese sniper in the area in front of the Hook. Most in his battalion felt it was tit for tat, since the night before, Cpl. John Gill, an RCR section leader bringing in his patrol back through a UN defensive line, had been killed by a Chinese sniper. Pte. Zuber settled down in the tunnels beneath the Hook position to sleep.

Also in the tunnel that night were a combat engineer named Connors and two South Koreans who had been assigned to work with him. At that moment, the threesome were resting. Connors had lit a candle and begun reading a paperback, The Perfumed Garden. Meanwhile, a fourth man, a signaller named Doug Rainer, had been given permission to take a cigarette break in the tunnel. He sat next to the sleeping Zuber.

About twenty new recruits were also in the area as part of a reinforcement draft from Canada. The replacements had just begun preparing their weapons for the night’s postings. One of the new men was told to prime a box of a dozen grenades in the tunnel. Around midnight, one of the grenades he had primed slipped from his hands. The grenade had a four-second fuse. Instead of shouting an alarm or tossing the grenade farther down the tunnel, the recruit panicked and ran out of the tunnel.

The explosion decapitated one of the Korean workers and severely wounded the other in the chest. The engineer had his leg broken in two places. The signaller had part of his foot blown off, and Pte. Zuber took shrapnel up and down his legs and in the buttocks. Oddly enough, when Pte. Zuber gained semi-consciousness, he was able to see in the tunnel. The body of one of the Koreans had sheltered Con-nors’s reading candle and it was still burning, providing a bit of light in the smoke-filled tunnel.

The Regimental Aid Post was already busy when the wounded arrived from the tunnel. The medical officer was working over sawhorses. Pte. Zuber, on a stretcher, was placed on the bunker floor next to the wounded South Korean labourer. A medical corporal approached, saw that Zuber’s pants were bloodied and asked, “What is it?”

“I think I’m okay,” Zuber said, and he pointed to the Korean. “What about him?”

“Oh, Christ,” said the medic, realizing how serious the Korean’s chest wound was. He immediately knelt down to investigate.

“Hey!” shouted the medical officer to the corporal. “Our own first!”

There was no argument. The corporal got up from the Korean, moved to Zuber and said, “Forgive me.”

Zuber was conscious enough to be horrified. Horrified for the dying South Korean. And horrified for the dilemma facing the young corporal. The two Canadians listened to the wheezing sound next to them; it slowed and then ended as the Korean labourer stopped breathing.

There was little time to grieve because, for Zuber, “emotion was a luxury we learned to give up in the front lines.” Later, at a Norwegian MASH unit, Zuber remembers a doctor smirking as he probed the wounds in Zuber’s buttocks. They took eighteen pieces of shrapnel from the bones in his legs and the flesh of his backside.

Three weeks later, sniper Ted Zuber was back in the line. The RCR war diary reports he “unleashed poetic justice today when he killed two Chinese [snipers],” one of whom was carrying the identification tags of Cpl. Gill, the RCR soldier killed on New Year’s morning. In the killing zone, the best a soldier could hope for was to even the score.