1951

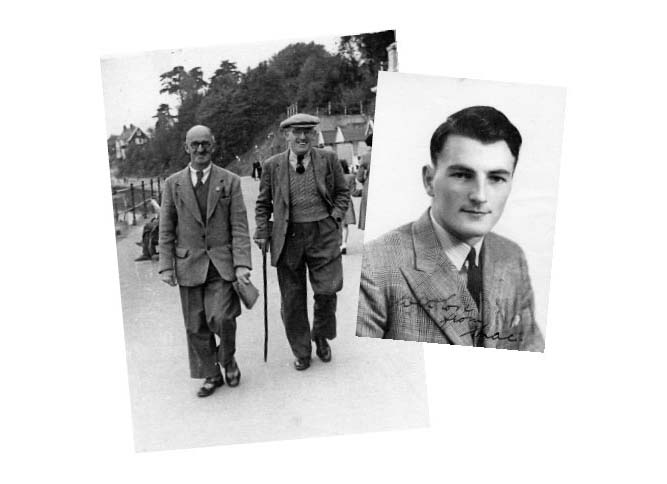

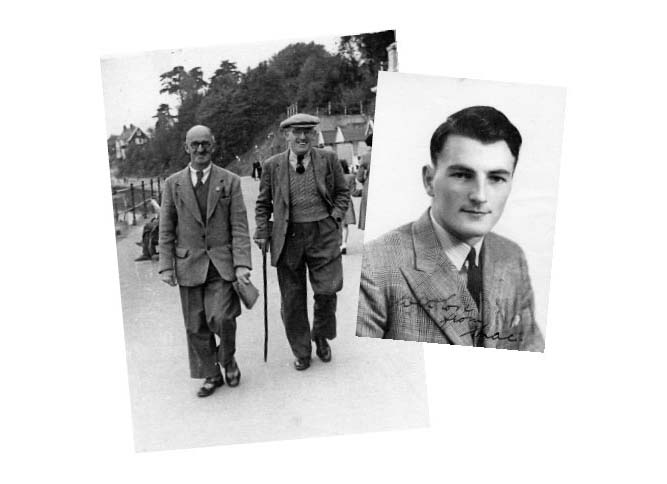

Uncles Mould, Marine Parade, Lyme Regis;

Frank 'Mac' Woodsford

Uncles Mould, Marine Parade, Lyme Regis;

Frank 'Mac' Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

How strange, sometimes, comparisons work. The February copy of Holiday arrived this morning, many thanks, just as I was leaving for the office, so I took it with me to look at on the bus. While I was working, I gave it to the cashier to look at (she's hardly anything to do this week, as the premises are closed except for hot baths, and the poor cashier on duty just sits and thinks and wishes for something to occupy her) and, as they passed her desk, most of the staff stopped and had a good horse-laugh at the Holiday Diet page.

I was intending to send you back one of the meals illustrated – either the breakfast of two pork chops and orange, apple and banana slices, or the dinner of two roast potatoes and roast beef, with a sarcastic question, 'Is this one meal or two weeks meat ration?' (which, over here, either meal would be!). But, suddenly, in came a customer as I passed across the hall and he looked at it, the cashier obligingly holding the book round for him to see it better, and he turned to me and said, 'Well, it looks very nice, but you don't do too badly here in England – you do get meat now and then.' I said, 'Yes, we do, but what I object to is that we got more meat "then" than we do "now".' He shook his head at such stubborn greed and said, 'Well, when I was a prisoner in Russia, I didn't have any bread for seven months. Bread, mind you.' 'You mean you didn't even have cake instead of bread, like Marie Antoinette? Well, I can understand that, but surely you're not going to say it was healthy for you?'

So, you see, a diet that seems inadequate to English housewives (and their husbands) seems wonderful to an ex-Russian prisoner of war from (I imagine) Czechoslovakia. And both would seem inadequate to an American. It's mostly a matter of point of view. You moan (just a little bit, not much!) because you only have toast and coffee and an egg and Quaker Oats for your breakfast. I have never had an egg and coffee and Quaker Oats for mine. Partly because I loathe and detest that boiled woollen underwear which is called Porridge, and partly because I have always had orange juice, toast, and cornflakes with milk since I was about ten years old . . .

I was amused to see in the newspapers that this week the London butchers are going into mourning for meat! Their shops are being draped with black, and they are having black-edged cards printed for distribution to their customers with their ration of meat, the cards reading, 'We regret to announce the all-but passing away of Meat from this Country', or words to that effect. According to the papers, people are getting really angry about this dilly-dallying with the Argentine. After all, we are charging them two or three times pre-war prices for the coal and machinery they buy from us, so why all this hypocritical screaming because they are charging us the same increase on their meat? And people are saying they'd rather pay the extra few pence a pound for meat, than pay eight or nine times the price for rabbits or ham or tinned Spam-stuff. It's all this dam' Gov. planning. To keep down the official cost of living, they refuse import licences for firms to bring dried fruit into the country. Then they grant licences to Eire and Holland to import what is called 'Dried mincemeat', which is ordinary dried fruit stuck in bottles and covered with a slight sprinkling of sugar. Ordinary dried fruit costs (when we are allowed to buy it) about 2s. a pound. This so called 'mincemeat' costs about five times that – and what makes us so mad is that it is the fruit sent over for us, and bought by the Government in bulk, and then sold by the Government in bulk (to Eire and Holland etc.) and then sold back to us at enormously inflated prices. You see, dried fruit could be classed as an ordinary item of diet, to count in any cost of living index. But nobody can say 'mincemeat' is an essential, so we don't count that. It's like saying, 'we'll take all the shoes off the market, and then nobody'll have to pay money for shoes and then they'll all save that much money and it will cut down the cost of living.' Then they'd put, say, Chinese wooden clogs on the market at umpteen dollars a pair, and we'd have to buy them when our ordinary shoes gave out, and we'd then get told off for such extravagance – fancy buying Chinese wooden clogs! What an idea, indeed! Bah! and likewise Pah!

. . . And now for home, and four days at home next week, with a type-writer and a big fire – the coal-man having called when we were down to burning twigs and yesterday's ashes!

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

PS Remember March 22nd's the date.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Looking over my old wartime hospital visiting reports the other day, I came across a report in which I had said, '. . . . . . I met this patient out in the street last week, when I was hungry and tired and rushed, what with going without my midday meal to do shopping for the patients, and running, or jog-trotting, nearly two miles in order to deliver their requirements to the hospital. Mark Garven was surprised, therefore, instead of getting a beaming hospital-visitor sort of smile, to get the full blast of my tiredness and exasperation with Canadians who wanted impossible things and weren't even grateful when I got 'em. He listened to me in silence, and when I stopped for breath said meekly, 'Well, you know you only do it because you like doing it – you wouldn't do it at all, otherwise.' And he was right. Whatever the trouble, I do my visiting because the joy it gives me is worth more than all the worry and disappointment and work.

Well, then, I write to you because I like writing to you, and because I like hearing from you and taking part, third hand, in your life in Bellport. If I didn't like doing it – or if I were doing it only out of gratitude for Rosalind's kindnesses, my letters would long ago have dried up or become stilted, dull 'bread-and-butter' affairs. So there is one chore less you can give yourself – that final paragraph in your letters thanking me for mine! Don't, for Heaven's sake, feel grateful for these Saturday Specials; our indebtedness is well balanced in that respect, so our thanks can cancel each other's out, see?

. . . It is raining again, and I'm all dolled up in my best suit and my silliest hat, as my brother and I are invited out to lunch today. Serves me right for not wearing a heavy coat – I came out in my suit and my fur titfer and I refuse to carry an umbrella since they don't match my suit. Expect next week's epistle to be even less coherent than yesterday's, as I shall by then probably be delirious with triple pneumonia.

In the meantime of course, I remain strong and healthy and

Very sincerely yours,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Yes, I know it's only Friday, but the way I feel today, tomorrow the family will be ordering wreaths, and I should hate to break the sequence of letters by not sending you one every Saturday until the last possible Saturday.

In other words, I am suffering; and oh, Mr B., I don't often suffer, but when I do, I make the most of it! Either I have

tonsillitis,

neuralgia down the r.hand side of my face,

fibrositis down the left of my head and neck,

abscesses in both ears,

insomnia,

and a hangover without benefit of spree

or I have a nice case of something or other not yet diagnosed. My boss is due back today, and I dragged myself down about ten o'clock hoping he'd catch the early train and be back so that I could go home immediately after lunch. Alas, it is only twenty minutes to five o'clock now and there's no sign of him so I don't know quite what to do – for to do another 14-hour day is quite out of the question. I do think four 14-hour days in a row is enough. I get home about 10.45, have supper in bed; toss and turn and count money, check tickets, deal with complaining customers, count some more money, check some more millions of tickets, add up and subtract, and generally have a very busy night until about three o'clock in the morning when I sleep. Breakfast is at quarter to seven, and after that is over and I am washed and dressed (not, I will admit, quite in my right mind this week) I go off to work and repeat the whole thing again.

Do you think I could be overworked, Mr B.? I certainly intend to hint so, when and if my boss turns up. Trouble with that man is that when the summer ends and we sink back exhausted he's full of plans for extra staff here there and everywhere to help us in the summer. When the spring comes along, he's forgotten last year and cheesepares as merrily as ever.

I finished South Wind one day over the weekend, I think. As I don't (yet) know Capri I can't compare the picture Norman Douglas paints of the island with the reality, but I should imagine it was a brilliant portrait if you take out the volcanic soil stuff and the smelly fountains. The characters were brilliantly drawn; and the arguments were brilliantly thought out, and I loathed the whole lot of 'em.

. . . This is a depressing and depressed letter, and I'm going to stop it this instant. Don't feel too sorry for me when you get it, for I shall probably be jumping the moon again by then. I hope you are well and busy with the yachts and the sunshine and the gay breeze.

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Work, work, nothing but work. And last week I was miserable because there was nothing to do but read with one eye (the other being buried in pillows and hot-water bottles) or feel miserable. So this week I have been miserable at work, for a change – one of the deepest down depres-sions, in which only two things prevented me throwing myself off the end of the pier. One, I can swim. And two, I think four pence is too much to pay to go on our trumpery pier, still in bits where they blew it up to stop the Germans using it in 1941.

My doctor allowed me to go back to work on Monday, at my earnest request, but forbade long hours or hard work for a bit. Today, therefore, is the first time this week I am doing evening duty, so my absence last week did somehow or other frighten my dear boss, since he is being so careful of my health this week! Needless to say, he didn't say it was nice to see me back. Nor, in fact, did he say anything except blow me up for writing what he thought was too friendly a note to thank the cashiers for the flowers they sent me. Apparently he can have a bit of slap and tick-le with them when the mood takes him, but I must always stand aloof, Olympian and Awful (in the original sense of that word) and, in short, give a good impersonation of a mid-Victorian Overlord. I was so mad I nearly burst into tears and went straight home to my doctor to ask him to take back his permission!!

Instead, I went to my own office and had a small weep. Just as I was blowing the old nose (my head being wrapped in a white wool scarf to keep out possible draughts) a woman I know walked in to ask if she might have a Turkish Bath and send her ticket in by post, as she had left her book of tickets at home. She looked a bit oddly at me, so I murmured something about an abscess . . . . . . hurting . . . . . . . bit run down . . . . . . and so on, and, to turn the subject, remarked on how very nautical she looked. 'Oh, my dear, yes,' she replied. 'I was all ready to go out on the yacht, when I stepped on the scales – and my dear, the most awful thing – I'd put on two pounds!! So I said to myself, "It's no good – I must give up the yacht today. I must get rid of that weight."' So, at great self-sacrifice, there she was to get that weight taken off by hot air and other people's efforts. Apparently she has taken up the canasta craze, and my dear, we sit and play on each other's terraces, in the sun, from about three o'clock until seven every day. My dear, it is simply lovely – you've no idea – and then you go home and are all ready for your dinner. But you see, all her friends supply tea and little fancy cakes to eat, and this dear lady isn't used to taking anything to eat with her afternoon tea (I suspect the effort of having to order them from the cake-shop would be too much for her frail strength) hence the extra two pounds.

. . . What a horrible mess the Socialists are making of this Persia affair! People of all kinds here are feeling disgusted. I daresay it's right in a way to say we have no rights in another's country; and that we exploit them for a profit; that they are entitled to nationalise their own resources. But are we right in letting them when so obviously they are doing it for the benefit of a few (or possibly for the benefit of a country they dislike as heartily as we do) and not for the many? As far as I can make out, the only people who will do well out of the Persian oil are a) the Sheiks etc., on whose land oil was found, and who get royalties, b) the Government and their friends, and c) the Persians who happen to work for the Oil Company and get housed, fed, and given hospital treatment as part of the company's universal methods. One paper, quoting a Persian employee of Anglo-Iranian the other day, said that he remarked he wouldn't believe in nationalisation of oil until his wages were two weeks overdue.

And today, when we have sent a cruiser to the spot, and Morrison has at last said the refinery would shortly have to close because of lack of storage space, the Persians seem to be getting a bit of sense. But why wait until now? It may well be too late.

On the other hand, the news from Korea seems to be a little brighter. I wonder if the Russians have other trouble-making elsewhere in mind, and wish to clear Korea off their plate before stirring up mud somewhere else. I also cannot help wondering what General MacArthur would think if the war in Korea comes to an end without the bombing of Manchuria etc. I hope he will be big enough to be glad not to have any more bloodshed.

Rereading up to here, I think possibly I should have added

d) the Oil Company

to my list of people who get benefit from the Persian oil-wells! I have an uncle who is an executive in the Anglo-Iranian, with fingers in a lot of other oil pies, and I gather from things he says that the oil companies (though he considers they are sitting birds for whoever likes to hold them up for a bit more in royalties) don't have to raid the petty-cash box for odd pennies.

Oh – news. I'm afraid General Jackson has been demoted, and renamed. In the local newspaper this week was an article about the cat at the Winter Gardens, who was being called upon to take part in an opera which was being presented there this week. The cat had to sit on a brick wall at the back of the stage, for how long I do not know. Well, on Wednesday I got a message from the Pavilion to say that I needn't expect Jackson over to see me this week, because he was far too busy. The Winter Gardens cat got stage-fright, so they sent Willie (Irving) Jackson and he was such a success in the part he was given two dinners each night he performed, with the Pavilion Supervisor waiting in the wings to escort him to No. 2 dinner. He turned up on Thursday morning (Thursday night being the concert night, his presence would not be wanted) and told me all about it, and how very simple it was to act on the stage when, like him, you had been brought up in the theatrical atmosphere of a large theatre!

And now I must do some work.

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

To show you the old ego is back to normal, here is an anecdote culled from the latest autobiography. Written by the head of Cassells, the publishers, the book is crammed full of memories of Victorian figures in literature, and extremely good reading.

The author writes of a friend, a doctor, who, when he was a student, used to ride to hospital on a horse-drawn bus, and paid the driver a shilling a week for the privilege of riding up in front with him. One day, as they were jogging down Holborn, the driver suddenly thrust the reins at this student and told him to carry on. The driver took a bit of string out of his pocket, and as the westbound bus came up to them, dangled it in front of the other driver's face. The second driver there-upon burst into a scream of abuse and obscenity.

The westbound bus passed, and the eastbound driver put his length of string back into his pocket, and took back the reins. Of course, the medical student couldn't bear it, so he asked why the string had such an effect on the other man.

'Ah,' retorted the driver, ''e ain't got no sense of 'umour. They 'anged 'is old man at Newgate this mornin'.'

Having got that horrific tale off my chest (I thought it would appeal to you, since the protagonists are all well and truly dead and therefore do not call, quite so much, for our sympathy!) thank you for your letter which came this morning, and for the snapshot of Victoria Regina of Bellport and her betrothed, the Rev. Eros. As to both looking as though they'd swallowed the canary, I can't say, but they did look a bit pleased, as though to say, 'Ah – got him!' or her, as the case may be. Betty Dall doesn't, in appearance, at all resemble the 'average' American girl; she has far too adult a set of features – so many Americans have snub noses all their lives, which are all right in extreme youth but a bit out of place as one grows older. I speak from experience. I can't pass comment on the Rev. Godfrey because I just can't see his face for his grin!

. . . My brother went to Wimbledon last Saturday. He is a very unimpressed young man, my brother, but he came back raving – not about Beverley Baker's legs; not about Miss Chaffee's chic outfit; not even about the tennis – but about Queen Mary!! Her complexion; her hair; the colours she wore; the beauty of her turnout (even if it is a bit out of date!); the exquisite care with which she timed her entrances and exits, so as not to interfere with the players in the least. She is a remarkable lady, held partly in awe, partly in affection by the English people. Rather more in affection now, as she gets older.

You'll have to hurry with your boat if you want to get in with the first swing of yachting. Or is the bottom-scraping, caulking and painting already done, and only the rigging to be put right? When we lived at Westcliff – a very pleasant residential suburb of the seaside town of Southend, right where the Thames joins the North Sea – the seafront (about six miles in length) was always edged during the winter with beached yachts. Around Easter, the smell of paint and tar and oil was terrific, and we all used loyally to pretend it was attar of roses and oh, ever so good for us.

. . . My brother (I am reminded above) put a pair of tennis shorts across the back of a chair about three weeks ago, and asked loudly if somebody would mend them – the edges were torn and ravelled [sic] and had already been adjusted once, to hide the first lot of torn edge. Mother and I eventually went into Committee and decided they were beyond help, and Mac would just have to belie his name and buy a new pair. We conveyed this decision to him. Sunday afternoon I heard him ask plaintively where was the key to my sewing-machine. I said sweetly, 'In the tray of my needlework box', and produced it for him. Next I heard him asking how you worked the machine, so I went in, looked at it, and said, 'Well, first of all you take off the lid and then you lift the machine off the floor onto the table and you find it much easier that way.' I gave him cotton, just to be co-operative, and he settled down quite happily to lift up the machine, look at it, put it back, put the lid on backwards and mend the shorts by hand!!! Since then he has told Mother twice, and me three times, how nice his shorts look. I can imagine they must be as short as those minute things little French boys wear! All because he won't spend about two dollars on a pair of ex-Naval shorts – he only wants them to wear when his others are being washed. And, do you know, Mr B., it isn't until you go back to his great-grandmother that you come to the Scots blood in my brother! Shows how strong the wretched stuff is, doesn't it? Like Scots whisky and their accent. I bought him a new blanket (badly needed) for his bed, and a pair of hand-knitted socks this week. I think he thought the package was, at least, a winter overcoat!! Yes, you're quite right, we do! Spoil him, I mean. I have promised to make him a shirt some time, when I get through with making Mother two jumper-dresses, two short jackets, altering three blouses for her, and making a skirt myself. Shall we say, 1955 for Mac's shirt?

Oh dear, I meant this to be such a superlative letter, to make up for the last two (which have been poor indeed) but it is being written during my third evening spell of duty this week – in patches, between running upstairs to see how the show is progressing, pushing the usherettes along with their preparations for the interval; finding lost people their seats, helping the cashiers cash up, taking peculiar telephone calls nobody else is free to handle . . . I must admit that by now (9.25 p.m.) I am more than ready for home, supper and bed. This year I staged a one-man revolt, and told my boss outright I refused to do evening work unless I could take at least two hours for lunch, so that I could get home and eat in peace and leisure. So I catch the bus about half past twelve, and get back to work on the 2.15 or 2.30 bus (2.30 if I know my boss is going to be late!). And it makes all the difference in the world.

Have a good sail today, and don't tear your spinnaker!

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

PS I have opened this letter to put on two postscripts. One, to tell you that I have a visit today from General Willie Irving Jackson, Esquire, and a message from the Pavilion Supervisor that since his stage triumphs he has become very vain, and when it is sunny, goes out and sits in a pose on a large rock in the Pavilion Rockery where he waits for holidaymakers to admire and photograph him! Secondly, it has only just occurred to me that, instead of being virtuous in writing you on that Friday I felt so ill, I was really being extremely selfish in spreading any germs I might have had – how awful if I really had had polio! I might have infected everybody through the postal services to you and the rest of Bellport. My humble apologies. I am glad I didn't.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . On Sunday my fond momma departed for a week's stay with friends, and left Jemima Muggins to look after No. —, brother, and two cats. Yesterday, for example (all the days have been about the same, some a bit worse but none any better) I woke at 4.30 a.m. in order to make certain I was awake at 6.30 to get breakfast. That's the awkward way my sub-conscious has of seeing that I keep my reputation for punctuality. Well, I got up at 6.30, produced breakfast for the cats and for ourselves by five to seven. Lay back in bed and ate my toast and drank my tea, and then up again for good about 7.25 a.m. to wash the dishes, clean up the kitchen (lick and promise) rush around dining room with a duster moving dust from here to there, put up cake in bag for brother's lunch; out at 8.20 to catch the bus to work. Left office at 5 p.m., ran all the way to the square to catch the bus, arrived home at 5.32 p.m., cooked new potatoes and green peas and laid the table, dished up dinner at 5.55 p.m. (special request, as Mac was due to play tennis at six and really wanted his meal about eight only he couldn't get me to co-operate). After dinner, wash dishes, feed cats, scald milk (no ice-box) wash milk saucepans, cool milk; wash milk bottles; replenish dining-room flowers, turn down beds, catch bus to get back to the square by 7.05 p.m. for the Symphony Concert.

I was so exhausted and hot by the time the half-time interval came along I just wilted and went home, where I lay panting for three minutes flat, and then set to work putting the breakfast things ready to hand, and doing some more flowers and tidying. Fell into bed about 11 p.m. and woke up again at four ack emma.

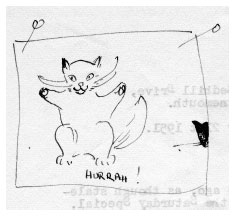

And that, Mr Bigelow, is why there just isn't any meat, or other substance, to this letter. There just isn't any to me any more. Today I left a little picture pinned to the front door, looking rather like this, for nobody could be more pleased to see Mother back than her two horrors. Freckles in particular has been firmly turned out of the flat at 8.20 a.m. every morning, and not allowed back until late evening – oh, way past his dinner time and way past his boiling point in temper. The half-cat on the right is Uncle Sam, afraid to come right out in the open . . .

Oh dear, my poor boss! He keeps saying, 'Thank you' this morning – a thing he doesn't normally do once in a blue moon. It's all because I'm cross with him, and he knows I am right to be so – we had a rip-roaring row yesterday. One of the male staff accused one of the women of lying over some trivial matter, and Mr B. and the man came into my office and we all set to. It occurred to me to ask a) why the woman should have lied, since there was no logical reason for a lie (the man had asked when a particular bath was filled with hot water, and didn't believe the woman when she had said 'nine o'clock') or b) why she should be condemned as a liar by both this man and my boss without so much as a hearing.

I, stuck mid-way between staff and boss, get ground into very small pieces at very frequent intervals! It must be quite the same thing as being a bit of coffee bean . . . . . . you get ground up small, and then you still get into hot water.

This is a very poor letter, and the only thing I can do is to see that it doesn't go on being poor any longer.

I'll try to do better next week . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . On the way back to Bournemouth on Monday I had coffee on the train, and a tall man came along and said, 'May I?' as he sat opposite me. Now there isn't much opportunity for an accent in the words 'May I?' so I couldn't tell from whence he came. Two other glum people came and sat at the other seats, and we all sat there glum and silent as English people so often do in a train. The waiter came up and asked, 'Tea or coffee?' We all mumbled, 'Coffee.' I longed to say to the man opposite me (who looked so interesting) 'Excuse me, but I see from the cleanness of your shirt you are an American – would you care to have the recipe for British Railway's coffee? You never know – the Metropolitan Museum of Art might like it. For art it surely must be, it cannot be made this way by accident – not every day, every week, every month of every year.' But I was so shy I didn't say anything and we all finished our mouthwash in the same glum silence we started. The fluid was hot and faintly brown in colour, but other relationship to coffee it had none.

When we had all finished, the waiter came round and demanded a king's ransom, and the man opposite me asked 'What time does this train get to Southampton?' in a broad American accent! So I was right, though very unkind to my fellow English for judging a man to be an American merely because his white shirt was so pristine. It is a fact, though – your shirts always seem so clean and new and freshly laundered. Perhaps ours are so expensive our menfolk have to wear them when they get shabby, or keep them on one day longer than they should (our laundries are another thing we don't boast about). I noticed in Canada the brilliant whiteness of shirts, though at that time I thought I was being unfair to Englishmen, who were severely rationed with theirs. Perhaps they still are, financially, when you compare them with Americans visiting this country. After all, you wouldn't wear your oldest clothes if you wanted to impress foreigners, would you?

Did you hear of the three little French cats, called Un, Deux and Trois? They went skating in the winter, but unfortunately the ice cracked, and Un Deux Trois Quatre Cinq!

Awful isn't it? I'll leave before you hurl that book at me,

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Thank you for your letter of October 10th, which came this week, and which delighted me with your tales of young Master Toddy and his ways. And writing of Toddy brings me to the Subject For Today – 'The Tragedy of The Bellport Riders'.

Now I can take any hint weighing over half a ton, and it was not through obtuseness that I did not react to yours and send you a second illustration of this famous ride. No, my reason was that I had had a brainwave, I thought. Why, said I to myself, do another silly water colour? Why not perpetuate the thing in clay?

So when term finished at the art school I begged a piece of clay and took it home with me. This I rolled and kneaded into a flat slab, on which I painstakingly built up bit by bit, in relief, a horse being ridden by Messrs T. Akin and P. Bigelow. I scratched (literally) in a back-ground of trees and children.

This was so much fun I asked myself once again whether it was good enough, and conscience (and inclination) said No. So I went across the town and bought 7lbs of modelling clay powder. It was horribly difficult turning this powder into usable clay, with no equipment whatsoever, but eventually I managed. And with the clay I modelled the whole thing in a group of figures measuring about 7 inches high by 8 inches long. This was very charming and I was so excited about it as I proceeded that I did it rather quickly, with the result that when the clay dried off, a couple of legs fell off here and there.

But did this daunt me? No! Indeed, No, Sir! I started all over again, this time taking extreme care. Finding, with this third attempt, that there was a space on the horse's back (behind you) measuring about 1½ x 1 inches, I modelled Missie and stood her behind you, barking wildly at something or other. For why should she be left alone and moping at home, while you two were having all the fun?

This third statue was, I flattered myself, delightful. I treated it as though it were an atomic bomb likely to go off if touched. How I got it to the pottery class, goodness only knows, but get it there I did, unharmed; and it sat on the bench and charmed all the other students and the two teachers as well. My head by now was reaching astronomical dimensions.

Everybody coddled that little group. It was given a tin biscuit-box to itself, where it rested in a bed of straw. It was labelled (the box) all over with DO NOT TOUCH notices, and placed high out of reach on a shelf. I used to stand on a chair each time I went to classes, and gently lift the box. Last Wednesday the box felt light and empty, so I hugged myself in anticipation.

And on Monday of this week, as I walked along the corridor, I suddenly saw on a chest further along, a little pile of 'biscuited' pottery . . . . . . the Bellport Riders. In ten separate pieces. In ten pieces, Mr Bigelow (and even so, two other bits were missing when I fitted them together, jigsaw like). I walked into the pottery room too miser-able to say anything, and as soon as I was seated Peter (our new teacher) came up and started asking about the way I made the group, in an endeavour to find out the cause of its explosion in the great heat of the kiln. We decided in the end it was probably my fault – that I had, some-how or other, got an air bubble in the clay of the horse's body, and, in exploding, the body had taken with it all the other parts of the group which had been broken.

I said at length, 'Ah well, it can't be helped, but thank you for all the trouble you have taken. Now I shall just have to be content with the relief-tile.' 'Oh, but that one blew up too,' said Peter. 'There were only two failures in the whole kilnful, and they were both yours.' 'Oh no, there weren't only two,' I said miserably, 'for I've just looked in the cupboard and my biscuit barrel has had its handle broken off.' Only three failures, and all of them mine. Why?

So I took my ten little pieces home, and I stuck them carefully together with glue, and I made a false left leg for you and a false left leg for Dogsbody (the horse) and a new tail for Missie. And then I painted it all with ordinary watercolours – a white horse dappled with grey. A red, red blanket. Toddy in red trousers (short ones) and a white shirt with red band around his neck and arms. You in grey-green trousers and a shirt striped in green and white, with a gay yellow kerchief, around your neck, dotted with black. Your 14-gallon Stetson (a 10-gallon was too small!) was in grey-green to match your trousers, and Missie, whose colouring I did not know, is white with black and brown patches. The horse has two feathers (red) between his ears, and a very naughty look in his eyes. The whole thing was then varnished with colourless nail-varnish, and reposes in state on the sideboard in my living room, with a large antique brass tray at its back.

It is the most charming thing I have ever done, and it was going to be such a pleasant gift for you. And now it is all in pieces. It's all very well for my family to say that misfortune, if well taken, is good for character. But my character, as you know, is too near perfection for it to need any improvement, by misfortune or any other means. Besides, most of the pleasant things that happen to me seem to happen without any deserts on my part; this makes it all the harder to bear hard luck when I feel I do deserve good – as though I need never bother or take trouble, because it will all come to naught, whereas if I just sit back, the only fortunes that come to me will be good ones, undeserved and unexpected. This, I realise, is a very lazy and bad philosophy to get around the place, and I don't really expect to adopt it. But it is disappointing, especially when I have gone to such pains (and believe me, for such as me, pains is the word) to keep it a secret from you.

However, when I got home last night from the cinema, I peeped in the living room to look at the group, and I suddenly said, 'I will not be beaten by a bit of clay. I will do it again. I will get it right!' and suddenly, as I thought all those intense thoughts, there popped into my head a method of getting the body of the horse without any possibility of it containing air bubbles. So next week I shall jut out my chin and confront the pottery teachers with my determination to try, try again. It will, of course, take many weeks, for the clay is so thick in diameter for the horse that it takes many many weeks for the stuff to dry sufficiently for it to be baked . . . I should imagine, with luck, I might do it by next Easter! It shall be my New Year Resolution. This setback is all the more annoying since my delight with my first attempt (prior to baking and blowing-up) led me to plan all sorts of other little figures – a caricature of my brother playing tennis; a sailor and his girl sitting on a bank under a tall tree – the tree trunk to be the column of the table-lamp, the shade to be the tree's greenery – a burlesque, in clay, of my fat cat asleep on his back. And so on. Full of ideas but inadequate to carry them out. You've no idea how exasperating it is, Mr Bigelow, to be fairly bright in the head but not capable of carrying through the ideas that arrive . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances (Brokenhearted) Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . I had a letter from my Canadian doctor, Keith Russell, last week to tell me he was in hospital having one lung out. That poor man can't do anything without annoying me! Even when he writes for sympathy he annoys me because that's all he's writing for. Says he somehow feels he's never to hear from my sweet self (that's me in case you wondered) unless he gets down to it and writes to me again. He had seen a play in New York and wrote 'yours truly witnessed the same in New York' . . . . . . Talk about English as it is tortured . . . . . . Oh dear, maybe I'm too particular, too fussy for this imperfect world, but I'd rather stay single and fussy.

The other day my brother was out of the Town Hall on Council business when, presumably, eleven o'clock came around and he'd finished what he had to do. So instead of going straight back to the Town Hall and having a cup of coffee when he got there, he went to one of the big stores in town for his elevenses. In the restaurant he noticed a girl he knew, who was sitting near a pillar, with a body just visible to the main part of the room. Mac walked over and said hallo, and found to his horror, when he got around the pillar, that she was accompanied by seven female friends! They were delighted!! Mac joined them for coffee, and three of them decided to have another cup with him. When the waitress brought the bill she handed it to my brother automatically (she must have thought he kept a harem, or was a stage producer) and he was horrified to find it was for 17 cups of coffee! Apparently the girls had been there some time. The girls said but oh Mac wasn't to pay for them all, it was ridiculous. Mac quite agreed, privately, but made a pooh-pooh fuss just for the record I imagine, and the eventual upshot was that all the gals pushed their contributions into a pile on the tablecloth and refused to take it back. So Mac gathered it up and paid the bill and left a tip and had sixpence left over for himself! He was as pleased with himself as though he'd just made a thousand pounds on the Stock Exchange . . .

Oh – pottery. I have compromised. I will not go back to Ballantine's decoration muddle class, but I have allowed myself to be persuaded to stay in Miss Gilham's throwing class. That means that I shall have to leave my pots at the college to be biscuited, but Miss Gilham has promised to get them glazed for me elsewhere . . . When Mr Ballantine came up to me on Monday he said, 'I am sorry about those two side dishes, Miss Woodsford' (those were the two intended for you, which were ruined by being put in too hot a kiln) and I said it really didn't matter because I had no intention of continuing with pottery in such frustrating circumstances. 'Isn't there anything you can suggest we do to make you feel happier?' I ask you – could I have said, 'Yes, get yourself a new character'? So I just waved my hand around the filthy studio and left it at that . . .

Somebody on the radio said the other day the reason Americans make their tea with little bags and hot water is because they never keep the same wife long enough to get a kettle boiled! And with that calumny I will leave you for now!

Sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

A special treat for you, this letter was to be. All in my own handwriting. But on trying out this new paper (I have thousands of aunts, whose minds run comfortably in the twin grooves of notepaper and hand-kerchiefs) I am not sure whether it is paper or blotting paper, so the letter must be typed to be legible.

Well, I don't know about you, but I'm very glad Christmas is over. I think Christmas should be a time for children, and having none of my own and none handy for borrowing in times of emergency, there was just Mother and I at home, and occasionally my brother to mope and gloom (he's always miserable in between parties and nobody knows what he's like at them because he sees to it that none of his family go to them) so we just moped too. And overate a bit, of course, though the Ministry of Food do what they can to discourage such a thing. Buying all our food as they do, we eat what they buy, and if we don't like it, then we're just too fussy for this world. So our 'roasting' fowl was definitely a boiling fowl; our potatoes were earthy; our Christmas pudding was nearly minus fruit (Ministry of Food forgot to import any!) and our nuts looked and tasted as though they'd been left over from the year before last. However, there is peace on earth and for that I am grateful. And for many other things – the rudest health possible, a clean airy town, a wonderful mother, a job, and a sense of humour. And, of course, you to tilt at from time to time . . .

On Boxing Day Mother and I walked along the promenade on the sea-edge, and oh dear, people just dripped with diamonds and minks and new fur-backed gloves and new silk scarves and yellow pullovers and bright socks. I dripped a new wool scarf and a new handkerchief! . . .

Did you listen to the King's speech? I thought it one of the best Christmas talks he has given, and there was almost no hesitation at all, and none of those awful moments when the whole nation was holding its breath wishing him the next word, and quickly . . .

I went, for the first time for months and months, to the cinema last night. A British film, rather light and flimsy, it was nonetheless good holiday fun. 'Coming next week' was a trailer of an American film apeing (the right word, but probably the wrong spelling) King Kong, and the audience just rocked. With laughter, which I don't think was intend-ed. I roared too, particularly when the trailer came to the bit where the enormous ape wrecked a Hollywood nightclub (breaking the lions' backs across a convenient window frame as one might snap firewood) and pulled down the orchestra on their platform, knocked out the ceiling, the walls, and, it appeared, 90% of the people there at the time. In the midst of all this carnage and earthquake destruction, walks the Heroine (yes, she's the type to deserve a capital H). She trots up to the great beast, and stamps her foot at him in annoyance, plainly saying, 'Oh! Joe Young, you bad thing, you!' I hadn't expected understatement from Hollywood . . . . . .

If this is to catch the mail, I must stop now. I remember now I wanted this letter to be more controversial than the last. And now that I've written the letter, it isn't very, though no doubt you will find plenty of bones to pick over.

So till next time, with more controversy,

Sincerely,

Frances Woodsford