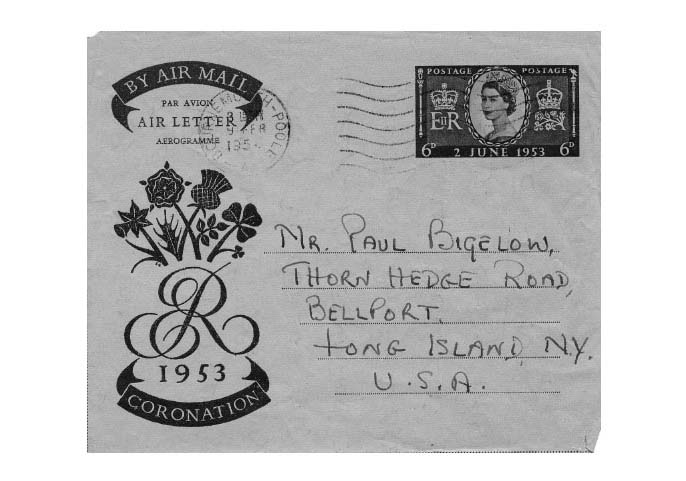

1953

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Mr Bigelow, I don't know if I occasionally give you the impression I am a very clever young woman. Just in case that is so, allow me to disillusion you this week: I am absolutely, utterly, entirely, completely, and wholeheartedly a washout as an upholsterer!

Mother gave my brother and me gift tokens for Christmas, which are exchangeable at certain stores for purchases to the value of the token. My brother didn't really want to have to spend his at a big store (he doesn't, as a rule, use women's clothes and knick-knacks! and the stores have only the smallest of men's departments) so I paid him cash for his voucher, and used both that one and my own and some more cash to buy remnants of green rep material with which to recover the sofa, Chesterfield or settee (whichever you prefer), and our large armchair. Also involved were millions of tacks, upholsterer's large-headed nails, webbing cord and what have you. I should have included iodine, bandages, nail oil (for growing new nails) and a spare hammer. As it was, on two evenings my brother just sat and watched me struggling because, as he pointed out, there weren't two hammers in the house so only one person could bang away at a time.

The sofa and chair are now recovered, I have not yet followed suit and am covered with torn flesh, broken nails, and dirt all over me, and the springs tied down to within an inch of themselves.

Mac 'helped' for a while by pulling out nails and dropping them into the mess on the spread-out newspapers on which I was kneeling, then he suddenly remembered an engagement – and brought out for me to see the actual invitation card, so he must have thought I'd view the engagement with a bit of jaundice – and departed in a hurry. After that, I was on my own, usually upside down in order to get the hammer to the nail. Next day, the dear man remarked icily that he thought I had not pulled the webbing nearly tight enough. So I made the sort of remark you can imagine, and he stayed at home an hour or so that evening, the better to instruct me in the art of webbing-pulling. I held down two of the coiled springs; he held down the third one, picked up the hammer in his right hand, and glared at me as I said brightly, 'Yes, dear, that's how Mother and I did it last evening. Now all you have to do is to pick up the nail in your teeth, place it where you want it to go, and give yourself a smart tap on the back of the head with the hammer. Or else grow a third hand in a hurry.'

Eventually he decided the webbing was quite tight enough, and went out. Eventually, too, I got the darn job done (more or less) and this included covering the easy chair. Mac suggested that instead of taking the bottom stuff off and working from under the piece of furniture, I should take the top off and work down. Unfortunately I was halfway through before I realised that this entailed cutting a line right through the present covering, in order to reach the stuffing. And then the stuff-ing had to be taken out and piled in dirty little mountains on newspaper all over the room. When the springs were disentangled, tied, and set firmly where they belonged, I put back most of the stuffing, and then the food parcels you sent me for Christmas came in useful again, for I had kept the boxes and the wood shavings, and these latter went in to implement the stuffing already in place. The seat now looks rather like that shapely Japanese mountain, but a few nights of Mother's weight plomped firmly in the centre will soon put that right.

And now the carpet looks unbearably worn and ragged! And, to be frank, I quite miss the untidy, homely appearance of our furniture, covered as it has been these last few years with a motley collection of travelling rugs, bits of old curtains, and the cats. Now Mother smacks the animals if they climb up, and it takes all the comfort out of home-life. Though, to be sure, it does give the human beings more chance at sitting on the sofa and chair than normal . . . . . .

I read your last letter, at first sight, as '. . . . . . I have a bird free lunch.' I too have a lunch table (non-stop) for sparrows at the office, and I have a poor little sparrow now feeding there with an injured foot. He holds his little leg close up against his body and hops on one foot and uses his wing as a sort of crutch. Trouble is the other birds in their greed are apt to push into old Hoppity, who overbalances and falls off the sill. Then he is too sorry for himself to fight his way back, so he gets a good feed only when the others are elsewhere, and that is rarely. If I could only catch him, I could take this bird to the Sick Animals' Dispensary (branches all over the country) where they could, perhaps, splint it and look after the little thing until the bone sets. Perhaps, though, if the bird keeps this bad foot off the ground long enough, the bone will set naturally and the foot will be of use again later. I watch for him every day (he gets out of bed late) but have no way of telling which bird he is except for the foot, so I won't know whether or not the foot has healed, once he starts using it again. Ah well, I suppose it's only one sparrow and there are plenty more. But I don't like seeing even a sparrow in pain and discomfort . . .

Now I must go; my boss has lost some book or other and claims I must have borrowed it. As I never knew he had it, it is unlikely, especially as I have never borrowed any sort of book from him in my life; but I shall have no peace until I find it.

So au revoir until next Saturday, and I hope you have recovered from your cocktail parties of Christmas and your gay New Year's Eve ditto.

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Graduate, School of Upholstery-Botchery, Inc.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . If this letter is more inaccurate than usual, it is so because I am typing it in the cashier's office as the duty cashier is ill and the other one went home before this one felt unwell. On Tuesday I went to my boss and said in the sweetest tone I could manage, 'Where would you like Mrs Mollison to work today, Mr Bond?' and when he glared and asked what I was talking about, I said innocently, 'Oh, she's the only person who's turned up today.' That'll teach him to shout at me for trying to arrange for a spare body about the place just in case yet another one went off sick. It's this wretched flu epidemic, which is really hitting us hard. I do hope you're not being fashionable. The World Influenza Centre or something is getting very upset because, though they say they usually can plot an epidemic, they don't know whether this one started on the Continent and spread to England or vice versa. As the patients feel just as badly one way as they do t'other, and as any plot they like to make only shows the facts after the events, I don't feel that it matters a great deal.

Did I tell you last week I was reluctantly going on a picnic on Sunday? Well, I was and I did and it was lovely. We went, as we so often do, over the Purbeck Hills in Dorset. It was misty when we started, on the 10.40 bus from the centre of Bournemouth, but the sun came out in odd moments when it wasn't doing anything else, and the mist wrapped the horizon around in a pretty little fuzz and comfortably hid the scars of war as the bus went across the moors. To reach the village at the foot of the Purbecks – Studland – the bus runs through Bournemouth and Parkstone and Canford Cliffs, all very la-di-da districts, then dives down to the flat Sandbank that is so called, crosses the mouth of the Poole Harbour by the bus ferry, and goes on for about three miles over wild and deserted moorland, with the long line of hills edging it to the south, and the arms of the harbour to the north. This moor is slightly undulating, and has a vivid blue piece of water called 'Little Sea' set in its brown and purple scrub on the left of the road – with the sea beyond the blue lake, and the white cliffs of the Purbecks in the distance. Hill after hill rises in the mist in pale grey, like so many scenes on a stage. And then we reach Studland and have to get out and walk on our own flat feet.

There was a cold little breeze from the north-east which chased itself around our back hair in most unfriendly fashion, but the climb to the top of the cliffs, and then up the long slope of the hill to the highest point, warmed us up quite satisfactorily. Gave us a good appetite for our lunch. I had brought a flask of hot soup, sandwiches and an apple and tomatoes. The soup was delicious, and so much better for a winter picnic than tea or coffee. We ate sitting in the sun under a broken-down bit of wall we discovered. It didn't keep off the wind (if it had, we would have been sitting in shadow) but it shut out 50% of the view, which was unkind. Immediately after eating, we went on, meaning to find a path which ran along the south slope of the hill, as we knew from experience that to go down into the Corfe valley meant drowning in mud in the only pathway open, and walking along the very ridge of the hill was chilly. We slid down the hill a few yards, and found ourselves in the warmest, cosiest, sunniest and most sheltered position you could wish for. So we spread our raincoats on the grass and went to sleep in the sun for nearly two hours! How's that for England in January?

Somebody I know, who is coming to England in March for his first visit to this country, asked me what sort of weather he could expect. I replied, 'Everything.' But even I didn't really anticipate getting freckled on a hillside in January, between two days when the frost was heavy and white and the fog came down in a blanket night and morning. Incidentally, I have never known so much fog as we have had in Bournemouth this year. Normally we get a damp sort of seamist, which drives in from the beach and disappears in the morning. But this month we have had really thick fogs (twice the bus services have been stopped for some hours, it has been so bad) and they smell like wet washing hanging about a house . . .

My brother has been very worried recently over a big decision he has had to take. He has discussed it with me, and with one or two friends, and we feel we have had to fail him just when he needed us, as none of us felt we could advise him one way or the other – it was a decision for himself alone. Most of us have felt rather strongly on one side of the question, that it is better to work where you are happy than to tie yourself to a better-paid job that you don't like. I know from bitter experience how miserable it is working with one man with nobody at work with whom to associate other than the boss! However, my brother has taken his decision – for more money – and, although I have been able to do nothing, his other friends have pulled strings to see to it that he is given a month in which to try out the new job before committing himself to it irrevocably. So they at least have been able to help when it was needed. After working about fifteen years (except for the war) in one department, in very happy conditions, it's an awful jolt having to leave in one day, which is all the time the Town Clerk has given Mac to clear up his outstanding work and move over to the other office. We are very proud of him – there were 150 applicants for the job, but the Committee decided not to consider any as they wanted my brother. Now it remains to be seen whether or not he can get along with his new boss, who is notoriously difficult when she's not being downright impossible. That is all very hush-hush and secret, so don't say a word to nobody, no how.

Now it is high time my missing cashier felt better. I must go and investigate.

Bye for now.

More next Saturday,

Fran

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Poor little Holland; it was only last week, I believe, that she said thank you very much but we don't want any more dollar-aid, America. And so few hours later, she is devastated and drowned. Our own floods are bad enough, goodness knows – I know Canvey Island as well as I know Bournemouth, and can imagine how awful a flood would be, for the whole island is like a flat saucer, with the rim only a few feet above the surrounding sea and a causeway usable at low-tide the only way off to the mainland. But Holland! One sixth of her land flooded, and such a little land, at that.

It was on Thursday last week that we celebrated the flight of that Canberra 'plane which took 22 hours to go from England to Australia. On Friday it was announced we were building two more passenger- carrying jet 'planes capable of transporting 150 passengers, 550 miles an hour. And on Saturday Nature decided we were getting cocky, I suppose, and sent a ferryboat, on a 25-mile trip from Scotland to Ireland, to the bottom, then went on around the coasts and brought devastation all down the East Coast, before hurling her waters point-blank into Holland. We are such little people, when it comes to a hand-to-hand fight with nature, aren't we? In spite of Assam Dams, and Tennessee River Valley schemes and Golden Gate Bridges, and Atom Bombs . . .

I've not heard even a whisper of a rumour from Rosalind about the possibility of coming over to England and/or Europe this year. Is the matter shelved or cancelled, do you know, or is she waiting for exact dates before telling me? Or, it occurs to me as I write, are the Akins going only to Europe and missing out England altogether and Rosalind doesn't like to say so for fear of hurting my feelings? You might tip me off if you know. You see, if they are coming to England, and Rosalind will have time to spare to stay with us (with or without Mr Akin) and their visit will coincide with our water show at the Baths, I must start working on the Boss quite early to advise him of the situation so that he will know what's coming! . . . He's awfully difficult about time off at the best of times, but early in the summer it's nearly impossible, for then we are trying to get settled with new staff and there are always the most ghastly muddles for me to sort out. He can be spared, but has no intention of sparing me at that point; so if he's got to have his mind changed I shall need time to work the miracle.

Last week I sent you a sarcastic cutting from the newspaper about the 'bonus' of margarine and sugar in honour of the Coronation. The next day a letter appeared in the paper which said:

To the Editor, Daily Telegraph.

Dear Sir, I am appalled by the sarcasm and ingratitude shown by people over the announced bonus of four ounces of margarine to celebrate the crowning of our gracious Queen. Surely, anybody, even of the meanest intelligence, can see that the quarter-of-a-pound of margarine has been given to us so that we can baste the ox.

I am, Sir, yours etc.,

Whereupon the subject has been dropped, it being really shooting sitting birds to take pot shots at the Min. of Food over this point. I will give them credit for one thing – they have taken sweets off ration this week, high time too, instead of waiting (as I suspect the Socialists would have done) to release them for the Coronation, with a big splash. And now that I can eat chocolate until I feel sick, I feel too sick (dentist) even to start. What a world!

Yours in a deep depression,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Hurrah! I got two fillings done for the price of one bilious-attack. Not being able to bear standing around the house doing nothing but think for one moment longer, I accidentally caught an earlier bus than usual, and arrived in the Town Square at 8.30 a.m., with half an hour to waste and a five-minute walk to waste it in.

So I walked through the Pleasure Gardens, and never were so many shrubs so thoroughly examined as they were on Monday morning. In spite of this, and despite talking to every cat I met on its morning parade, I still arrived at the dentist's at six minutes to nine. His nurse was still struggling into her white coat, but at least the waiting room was warm and there were magazines to look at. But no, Mr Samson has returned to live in the lovely flat over his offices, and hearing I was already there, he popped down on the instant and got to work, so that by 9.15 when the next patient was due, two teeth had been drilled, filled and declared saved for the time being. After that, it shouldn't be so bad . . .

Last night I attended, in an icy hall in an icy evening, my first lecture on Civil Defence, and now I have no worry at all about the future. The day war breaks out I shall just simply die of fright. All my little problems will be solved, just like that. Actually, the lecturer made everything seem quite simple. Nobody asked any questions except, of course, me. I said, 'You have described how to deal with an ordinary fire-bomb on an upstairs floor; you smother it with a wet sack and spray water on the edges of the sack – not directly onto the bomb. Well, how do you stop it burning its way through the floorboards into the room beneath?' The lecturer said, 'You don't.' Easy as all that. Of course, we gathered that that was just a little ordinary fire-bomb without any explosive gadgets, and not a phosphorous one or an oil bomb nor an atomic bomb (nobody mentioned hydrogen) . . .

Yesterday I went to buy some more turpentine for my painting, and as I came away one of the attendants in the shop rushed up and said, 'How's it going?' He's rather sweet – every time I go in he comes up to ask what progress I am making, and when this time I told him I had finished 'six masterpieces' I'm sure he was as pleased as me! Then I went to the post office to send Rosalind a cable for her birthday, and found to my dismay that the old cheap night-letter-rate no longer applies, and the cable was a very expensive mode of communication. I wouldn't have sent it at all but for the dock strike in New York which might have delayed the present I had sent, so I wanted at least something to arrive for the day . . .

Hope you remain well and happy.

Sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Today – it's Friday today – a letter came from Rosalind which at last disclosed her plans for a trip to Europe this year. She just couldn't have chosen better dates, so far as I'm concerned, for she arrives at Southampton on a Saturday, which I intend taking off in order to meet her and escort her to London. And she leaves on a Friday, and if the ship sails after midday I shall be able to rush up to Southampton (taking Friday as a half day because I would be working all Saturday that week) and wave a damp pocket handkerchief from the dock. She says she is coming to Bournemouth 'for a night and a day', so already I am trying to organise a month's sightseeing and entertainment into one day and one night. You hustling Yanks!

Just like the English – to say 'No, it can't be done'. I decided to escort Rosalind up to London on the boat train, and telephoned a local travel agent to ask how I got a ticket. They were highly amused, and horrified, in about equal parts, that anybody should even consider such a thing permissible. So I stuck out my lower lip and got to work, determined to go on that boat train if I had to ride the rails on it. Eventually, I got on to some department or other at Southampton Railway, and they said of course I could go, just buy a ticket in the Dock Shed. Oh, they said as an afterthought – I'd have to get a permit to go into the docks in the first place, did I know? I said yes I did know but that the last time I had met somebody I'd got into the docks on the strength of a beaming smile only. 'Oh yes, that helps; but bring a Pass as well,' said the man the other end. So now I am all set, and there is only a little matter of several weeks to get through before the Great Day . . .

Well, my brother has at last made up his mind. He will take the new job offered him. The glint of money was too much for him, poor soul . . . He is now Deputy Children's Officer, which is quite a step up from being a Committee Clerk, putting him second-in-command of a Department as it does. Of course, come to think of it, I suppose I'm second-in-command of the Baths Department, but nobody thinks anything of that, as it isn't official and it's only in the salary line that it shows up. And, being female, I have to be so very, very careful not to tread on the corns of sundry Engineers, Foremen and suchlike temperamental creatures . . .

I am deep in another biography, this one of Whistler. At this distance, and safely out of reach of his acid tongue, I find Whistler's rudenesses most amusing. Especially did I laugh at the account of his being asked by a very rich man to go around his picture gallery and give his opinion on the collection. Whistler accordingly was taken around the gallery, and at each picture he said, 'Amazing!' all the way round. At the end, he added to his terseness by saying, 'Amazing – and not even an excuse for it, either!'

I'm very sorry, but I can't write any more this morning. For some reason or other I feel most depressed, and my thoughts keep flying to troubles and worries and miseries. Perhaps it is a combination of staff troubles . . . and the misery of Civil Defence lectures, during which the students laugh now and then but merely as a form of nervous release. And the weather is enough to depress the Empire State Building – you may have had a fine, mild winter, and I believe Scotland has, too. But what you've left over in the way of horror has been heaped upon England with a vengeance, ever since the bathing belles got frostbite at the end of last August.

Pah! I shall go out and buy a bunch of daffodils on my way home, just to pretend spring is here and make us all feel better . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Two extracts from my collection of Mother Woodsford Whimsies this week; first, I asked her how her new teeth were getting along, and Mother answered, 'Oh, they're just fine, I wear them all the time except for eating.' Second, when I heard dimly this morning the radio announcement of Stalin's successor, and sleepily thought the name began with a B (I was thinking Beria, head of the police) and called out, 'Who was that Mother?' 'Oh, Vishinksky, dear, I expect,' said Mother cheerfully. Presumably that was the only Russian name she could remember offhand, but I must say it doesn't sound very much like Malenkov, even to Mother's ears.

I don't know about you, Mr Bigelow, but I felt a sudden feeling of gladness when the first radio announcement of Stalin's stroke was heard, followed a little later by a smaller feeling of self-revulsion that I should feel glad about anybody else's misfortune, even somebody as evil as Stalin. There's no need for me to be horrible merely because he was. I wonder what will happen if there is another world, and it is one in which we are cognisant of our life on this one, and recognise our faults and mistakes? Won't Stalin be taken aback? I wish we could always keep the faith we have so strongly as children. Mother likes telling of the time I was reprimanded for kicking my way delightedly through piles of autumn leaves (slightly wet and probably muddy) and said cheerfully, 'It's a good job the Lord Jesus isn't here today. He would think it a mucky place.'

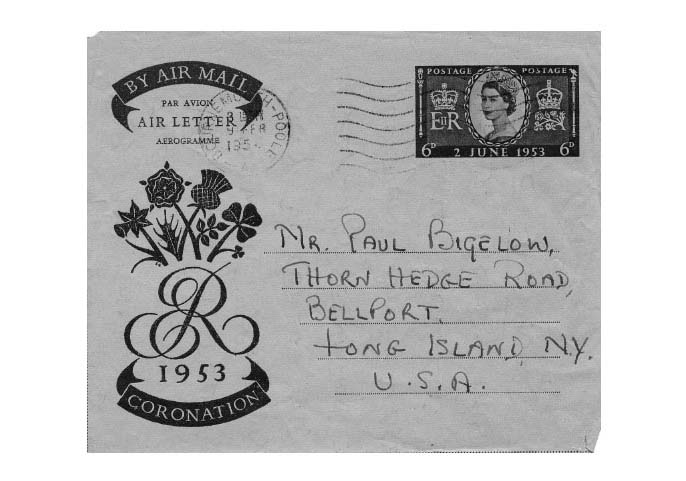

The latest copy of Holiday arrived this morning, just as I was getting out of bed. So I only had time to turn to Toni Robins's page on 'Lingerie for Travelling' and gape at the slips and nightwear. There was one – no doubt you turned over the page hurriedly, so you won't remember it and I shall therefore insist on describing it – very fitting underslip, with an enormous frill around the bottom of embroidered nylon, which looked good enough to wear outside the dress. Either that, or one should become a Wicked Woman in order to give other people the benefit of looking at such pretty things. So I sighed and put the book down, moved the cat sufficiently to crawl out of bed, and the day had start-ed. As I put on my slip I stepped over and looked at it in the mirror, and I looked something like this:

I will admit it was a gift some two Christmases ago and I thought the other day I really ought to wear it a bit before it falls to pieces with old age and lack of use. Besides, this way I am giving my nylon slips (very plain, but very serviceable) a much-needed rest. If ever you see a blue banana, you can give a small gasp and walk up to it and say, 'Why, Miss Woodsford, I wouldn't have recognised you!'

. . . Civil Defence lectures progress from bad to worse. Last week we were given a horrific booklet on Atomic Warfare, and this week, before I'd got over that, we had 'Chemical Warfare', and next week I am warned we get 'Bacteriological Warfare'. Perhaps they will finish up with the Technique of Mass-Grave Digging. Life promises to be most complicated; last night we were told what to do in a gas attack. The main things are, put on the victim's gas mask (or your own), get out of the contaminated area pronto, strip off all clothes, hose-pipe down, put on fresh clothes and Bob's your Uncle. Can you see us all going around with a fresh set of clothes in a gas-proof bag, a wet pocket-handkerchief (for dabbing gas off odd people found around and about) a hose-pipe and stirrup pump for hosing-down, and a bucket of water in which to push victims' heads so that their eyes get washed out. Oh yes – we should also have a feather for tickling their throats to make them sick if they've inhaled or swallowed any, and our instructor said they'd tried that on him and it didn't work so he recommended salt and water or castor-oil instead. That means a packet of salt and a bottle of castor-oil to add to the rest of our equipment. I still think my idea of dying on the day war is declared is by far the best way out. I don't mean to be flippant, but these things are so unbelievably ghastly that they really cannot be considered seriously.

Looking at the programme Rosalind appears to have mapped out for her all-too-few days in England, I can quite understand why Mr Akin feels no need for culture (being Harvard). Rosalind will be here in Bournemouth one evening and the main part of the next day. She wants a) what she calls 'a bath' and I suspect means a bathe in the sea, b) to buy an antique sideboard, c) to see some famous gardens, d) to have lunch in an English pub. I am saving up to buy a stop-watch. Am also panicking slightly at the notion I might not pass my driving test in time to take her around. Daresay all will be well, though.

Hope all is well with you, too,

Yours sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

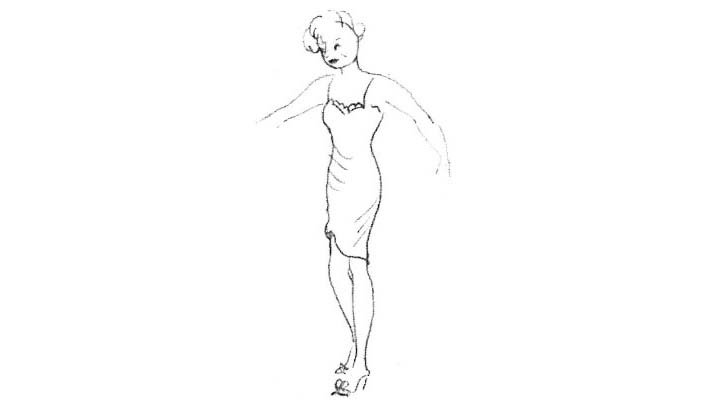

If ever you get a warm fire burning in Casa Bigelow – one that is not authorised, I mean – just let me know and I'll come over right away with my little stirrup pump, and my even littler hatchet, and put it out for you. Me, thoroughly experienced putter-out-of-fires. Since Civil Defence class last Saturday.

Eleven years ago, or thereabouts, I reluctantly bought myself a pair of slacks for fire-watching and air-raids in general. I dislike women in trousers, and myself especially, but they have their uses in such troublesome times. Since 1945, however, mine have reposed with moth balls in the rag-box. Two weeks ago I fished them out, cleaned and pressed them, and to my joy discovered they still fit! I think they must fit a little more closely than when they were new, for I know my weight is up 15 pounds or more over wartime years; but they fitted well enough.

So I clad myself in them on Saturday and rushed headlong after luncheon, full of good food and peppermint, to the place where the local Corporation people burn our refuse, and where a shed is placed at the disposal of the Civil Defence crowd for training such as me. I was the only one (apart from two men) to arrive wearing trousers, but we all finished up wearing navy blue boiler suits (men for the use of ) so I was practically the only comfortable woman present. Especially as I have such large feet they almost fitted the rubber gumboots we were also made to wear. Two of the women have tiny little feet, and in spite of stuffing the toes of the gumboots with their gloves, they could only proceed by shuffling along. When it was their turn to be No. 4 in the team (the water fetcher) we had to hold up the fire until they had shuffled the fifty yards or more to the water faucet and back.

Being silly-like, and nobody else showing any signs of volunteering, I went first. There was a small tin shed, with a corridor at the back and a door opening from this into the main room. This latter was fitted up with a furnishing scheme I don't think Park Avenue would approve of. There was a large armchair, sort of greeny black in colour and circa 1900 in years; there was a sofa of completely indeterminate shade and no pedigree whatsoever; there was a little table, and there was a pile of wood shavings. In one corner was a small incendiary bomb which the instructors lit, as they did also the piles of wood shavings. When they thought it was nice and warm and smoky one of them yelled 'Fire!' and this was my cue. I dashed (at least two yards) to the door in the corridor. Opened this a trifle, reeled a bit, recollected myself and shouted 'Water on'. Remembered I was English, and hastily added 'please'.

This is the opening scene. If you would like time out now for a drink or a smoke, please do so. The three-piece orchestra will play (probably 'In a Monastery Garden') during the interval. If your appetite is now sufficiently wetted, we will return to the scene of the conflagration.

In Scene 1, Act 1, we left the gallant team (No. 1 to put out the fire, No. 2 to pump the water, No. 3 to keep dashing up to No. 1 to ask if she is alright and get her thoroughly annoyed at so much interruption, and No. 4 to be water-boy and slop gallons over No. 2's feet. Hence, possibly, the gumboots) battling with the fire.

After poking the end of the rubber hose through a crack in the door, which I had opened a trifle and propped open by one foot, the incendiary went off. We knew it was going off, having been warned that the Germans, finding we treated their little toys with disdain, soon started fitting small explosive charges to the bombs, which put paid to the fire fighters if they were too close. Just the same, the harmless 'bang' which was put in our bombs, still made quite enough noise for me. It was my second cue; this time I flung open the door and myself onto the floor inside, narrowly escaping a gory death by falling on my little hatchet. This I was carrying in my breast pocket, as the boiler suit was made for a man and the ordinary pocket opening didn't coincide with my own slacks' pockets by at least six inches. As the boiler suit had no belt, the breast pocket was the only place to put it, and very uncomfortable it is, too, I can tell you, dashing about horizontally with a hatchet missing one's nose by millimetres.

Once on the floor, I was kept busy playing the hose on a) the bomb, b) the pile of shavings, c) the sofa, and d) the chair. The bomb got most; we only shot a few vicious squirts at the furniture, which wasn't difficult to put out; though the chair did start up again after I had finished, which was a Black Mark to me. The bomb spurted and glared and fizzed and generally behaved like a firework. I had time to appreciate its icy blue flame, and to think how beautifully it turned to vermilion on the edges. Once I even managed to score a bullseye with my little shoot of water, getting right around the bomb and down its throat. It spluttered most indignantly. Presumably that's not playing fair. Of course, I don't suppose I really did it much harm – you can't stop an incendiary once it's burning, you can only hope to stop it lighting the surroundings, which of course we all did quite satisfactorily.

Finally, the bomb having exhausted itself, and my demands on the water supply having exhausted the pump-operator, we declared it a day. 'Water on' as a small flame spurted up, putting its tongue out at me. Then, 'Water off again, please!' and I trotted out, slightly dirty and smoked like a haddock, to say 'Knock off and make up' in approved style, and give way to the next victim.

It was all surprising fun, once the first few seconds of natural flummox were over and one discovered that the bomb didn't come at you, or throw flames all over the place. We all got thoroughly wet (leaky pumps, of course, and sloppy carrying of over-full buckets) and we all feel now confident of coping with anything this side of Hades. Of course, if another large liner goes up in flames, I don't think I'll volunteer to be the first to go and put it out, but any time you have, as I said at the beginning, a nice cosy woman-sized fire, send me a letter. Better send it airmail, in case the fire gets too big in the interim.

I am enclosing a few sketches from life which possibly you could sell for millions of dollars to some foreign power interested in knowing exactly the sort of people they would be up against, in the event of you-know-what.

Probably my sketches would be the cause of lasting peace, if properly shown around and about. I give them to you with that in mind.

Last night, Friday that is, I went through the Gas Chamber. That in itself was nothing – just a small bare room with tiled floor and walls, crowded with seven people and one instructor all looking like things from Mars. But the after-effects were most unpleasant, for we came out with the gas impregnated on our thick coats, and as we sat in the lecture room afterwards we were all, instructor and all, weeping like servant girls at a sob-stuff film. Only, we had more cause!

While I came to the conclusion last week that tin helmets were most becoming, having caught a glimpse of myself in a mirror as I filled buckets of water in a room, I didn't need a mirror yesterday to tell me that gas masks are not the thing to buy in the spring when one needs a morale tonic. The instructor said to me, 'Have you had your mask fitted?' and I answered bitterly, 'Yes, don't I look like it?' knowing full well that my freshly washed hair was not lying flat or smoothly fitting like the novelist's cap.

Ah well, that really is all for now. More next week. Best wishes, and I hope you are well and happy,

Yours sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

In the days of the Tudors, women wore (so I am told) iron stays with which to restrain their figures. Today, April 4th 1953 as ever it was, I am using metaphysical mental iron stays with which to restrain my remarks, and I hope and believe you will appreciate and applaud the care with which I tell you the following tale.

Last Sunday, about five minutes before luncheon was to be ready, I was called to the telephone in a neighbour's house, to find my brother on the other end. 'I'm at the Queen's Park Garage' he said (I'd never heard of it) 'and there's a 1934 Ford 8 car here I'm thinking of buying. What do you think?' I asked if he had Dez with him (Dez is a depart-mental manager at one of the big motor firms in the town). No. I asked if he had Vic Hill with him. (Vic Hill is a skilled amateur motor mechanic and driver.) No. I asked if he had anybody with him. No, but he'd looked under the bonnet and the motor was a reconditioned one and had only done 100 miles. The tyres were fair. The bodywork poor. Somebody was coming back in ten minutes to make a decision. What did I think? Not much, I said, so he went off rather disconsolately saying he'd do nothing about it. And half an hour late for lunch he turned up, having bought the motor car!!!

It was delivered on Tuesday, and now reposes in a garage along with half a dozen other cars, for all the neighbourhood to see our shame. Mother and I have inspected it, and I have named it (privately, Mac doesn't know for the sake of his self-respect) Hesperus.* Hesperus is black. More or less. Under the black, where the old paintwork has not been properly rubbed down, it is a sort of petrol-blue colour. And under that again, is a grey undercoat, patched here and there with a bright shade of rust. Mac says gaily that the speedometer cable seems to be broken (did the garage proprietor recognise the pigeon by its bright green colour when it wandered in that Sunday, I wonder?) and that nothing but the anometer works on the dashboard, and that the trafficators don't work. He hasn't tried the windscreen wiper, but would you place a small bet?

* Editor's note: a name inspired by Longfellow's poem, 'The Wreck of the Hesperus'.

. . . We all went to the theatre last night (the first time Mother and I had had an opportunity to look at Hesperus) and Mac was the last of the party to arrive. He whispered to the friend sitting next to him, 'Are they annoyed? What do they think of it? Are they disappointed?' so apparently, in spite of a sphinx-like face on the matter, he is a trifle worried. To pacify possible sisterly remarks, he came out with two paper bags containing loose covers for the two front seats, saying blandly he was paying for them. That leaves us with two maroon-covered seats, and a navy blue back bench and a strong hint that Sister might like to provide maroon loose covers for the rear, I suppose. As the rear seat covers, I see from the catalogue, cost exactly the same as two front seat covers, Mac's generosity in paying for the latter wanes a trifle, don't you think so?

There is, I suppose, just a possibility that when we clean the thing up, and have the dashboard instruments put right and the windscreen renewed (broken) and buy three new tyres and new mats for the floor and paint for the paintwork and polish for the rest, the car may look presentable. I sincerely hope so, because it is already taking all my spare money and leaving me with about £15, £10 of which is earmarked to pay for Mother's teeth work. Money doesn't worry me, and I don't really mind if the car falls to pieces tomorrow, but if it does I know Mac will feel terrible about it, and it would be depressing to have to start saving for a car all over again.

I have warned Rosalind that we have bought a 1934 Ford 8, but at that time I hadn't seen Hesperus. Could you break it gently to her when she visits you next month? Tell her to pack, say, a suit of dungarees with her Minks when she comes over, so as to be more in keeping with Hesperus.

Later. Well, I think I know the worst now, having spent Good Friday afternoon cleaning Hesperus. You cannot lock the car. You cannot open the nearside front window as the winder is broken off. For the same reason, you cannot altogether shut the off-side rear window. The back seat is held to the frame of the car by one very rusty hook; I suppose the passenger in the rear holds it in place normally, but any passenger who sits on those springs more than a hundred yards has my admiration and my sympathy. The front off-side headlamp doesn't work . . . The rear light is suspended by a single wire, waiting for the first bump in the road. Mac says there is an electrical short as the battery is discharging all the time. This, presumably, means re-wiring the junk heap or always starting up with the starter handle and hard work . . .

Apart from that, I find I have no friends near enough to ask them to come out with me when I practise, and as in England a learner driver is not permitted on the roads without a licensed driver alongside, the problem is becoming acute as to how to learn to drive before Rosalind arrives. I have quite given up all idea of ever getting any money for the junk heap when we save up enough to buy something a little better, but the state of the thing in itself is very depressing. And I know that friends of his must have told my brother a few facts of life, for he goes around in a mist of misery and seems to have no interest in the car whatsoever, all of a sudden. Ah well, never mind, never mind . . .

There was a great deal I wanted to put in this letter, but matters are crowding in on me which require immediate attention. I'm not working this afternoon (at least, I think not) so hope to go out and buy a bright yellow hat, to cheer myself up in contrast to yesterday's mournful cleaning of Hesperus.

I hope you are having a pleasant Easter. I was getting quite worried about you, it was so long since your last letter; but the very day I wrote Rosalind and said I hoped you weren't ill, a letter arrived, proving you were full of zest, knocking women down in grocery stores (by frightening them, touching them with the finger of scorn or something!) writing long letters, reading many books, and generally being a very busy man.

Happy Easter (bit late, but never mind, never mind).

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

From many years past, the parcel postman and I have been on very friendly terms. Whenever I see him up the road I call out – 'When're you coming to see me again?' This morning he called next door as I was finishing my morning face, and I sang out of the open window 'Come along down-a-my-house!' in a cheerful way, and he answered 'Just a moment!' And lo, he did come along-a-my house (or whatever are the words of the song) and delivered a parcel from you to Mother. On being opened, it looked as if the parcel which arrived the day before Good Friday was the entrée, and this package contained dessert, the sweet, or 'afters', depending on the class of household. We were particularly delighted with the cake, which we know (you sent one at Xmas, remember?) is mouth-wateringly filled with fruit; but M. and I were also very, very pleased with the tinned and dried fruit and the shortening, which seems so much fatter than that we normally see over here.

But honestly, Mr Bigelow, please don't do it again. I know Rosalind, when she arrives, is going to be very surprised to see how healthy we all are, and how well fed. And I would hate her to feel – and so would you, I know – that we had been taking your food parcels under false pretences. After all, we can buy nearly everything we want now: we are rationed only by money; and luxury goods are just as expensive to you as to us, so why should you continue to pay high prices for things we don't or can't buy for their cost? Please, I do want to feel a little bit independent and not all on the receiving end all the time. Will you help me? At the same time graciously accepting (!) our most sincere thanks for both entrée and afters! How about dropping in one day for a coffee?

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . The day of the test dawned. I know that quotation usually runs 'the day of the test dawned clear and bright', but my day jolly well didn't. It was raining bucketsful at seven o'clock, and deteriorated rapidly, so that by lunchtime it was blowing three parts of a gale and the rain was horizontal. There was not a vestige of a hope of its clearing by 2.15 (zero hour) and I set off with my instructor for a last trial test at 1.30 with what little courage I had oozing rapidly out of the soles of my shoes. I did the trial run almost without fault, but that was no help to the Examiner, a dour and silent man, probably put that way by all the impossible drivers he has had to sit beside and suffer with all these years. The test run proper was never taken, I should imagine, by two more miserable creatures than the Examiner and myself. He because he was that type (my instructor said, 'You've got Poppa to examine you, but don't take any notice of his pig-like face, he's really quite a nice chap underneath') and I because of the butterflies having an orgy in me and because I got soaking wet through the open window. And the window was open so that I could make manual signs whenever told so to do. Actually, the instructor at one time said only to use the automatic traffic signals; then he said only hand signs, and lastly he said use what I like. I did all the way through, anyway, having been taught to use very definite hand signs backed up, at the last minute, by the trafficators to leave both my hands free to use on the steering wheel. My starts from scratch (and, going over the route this morning, I counted at least twelve in the half-hour test) were more like a jet aeroplane take-off than a smooth-running car. I twice stalled the motor, due to the fact that the gale was making such a din I couldn't hear the engine and know when I needed more gas. I touched the kerbstone in reversing. And, of course, with my years of cycling still strong in my mind, I wove my usual way along the roads, rushing back to the gutter as soon as I passed any standing or moving vehicles . . . However, I believe my work in traffic was good; at least I never had to brake suddenly because I had got myself into a traffic jam I didn't see approaching. The gale kept a lot (chiefly cyclists and pedestrians) off the road, so my good traffic work was more the result of luck than any cleverness on my part. We returned to whence we came, still with two completely miserable creatures in the car.

And there, while I sat in misery and wetness the Examiner cross-questioned me on the Highway Code, which I know backwards, and I believe I got full marks for that. At least, try though I might to answer quietly and slowly, my answers just rushed out because I knew them all so well. It was rather disconcerting to have an Examiner, who obviously knows all the answers himself, saying in a mildly interested tone, 'I see' to all my answers. On asking my instructor later, he said all the Examiners do the same – they are taught never to say 'Right', or 'No, that's not the answer' because that might lead to arguments, and they Never Argue With The Driving Applicant.

Eventually, after weighing me up and my answers and all my faults, the Examiner said he was giving me the benefit of the doubt, and I PASSED! For my own part, I would have failed myself thoroughly and absolutely, so awful was the co-ordination between clutch and accelerator on the test run. However, when he pointed out that there was considerable doubt, I did murmur something about being ashamed of my roughness, which was worse than I had ever put up before, and perhaps, as I hadn't offered any excuses before hearing the verdict, the Examiner felt that his judgement was not misplaced. Provided now that I never let my driving licence lapse, nor hit too many pedestrians in any one year, I can now drive for the rest of my natural life.

And, of course, another good thing is that I can now fasten all my waist-belts two notches farther back than a couple of months ago . . .

Yours very sincerely, and licensed car driver,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

As they say, the Devil looks after his own. And on Saturday morning, when I had finished my letter to you and gone home, what should I find but a cash refund of three shillings awaiting me from the Transport Dept (I had returned an unused bus season ticket some weeks before, and had almost given up expecting them to do anything but frame it) which successfully swelled my purse to finance my travel and eating until Wednesday, when my Savings Book came back and I was able to withdraw a pound or two from the Savings Bank. One nice thing about living down on my low financial level; the least little uplift and you begin to feel like shaking hands with the Whitneys and the Du Ponts and the Rockefellers on equal terms.

On Saturday afternoon my brother said would I accompany him (as a fully fledged test-passed car driver) to the War Memorial Homes (of which he is honorary secretary) where he was attending the opening of a hall. So we climbed into Hesperus, we climbed out again and wound her up, and off we set. And oh, Mr Bigelow, I now know why Mac failed his test!! He is a two-wheeler where corners are concerned, and when Mother said one day this week he had worn out the sole of one of his shoes and Mac said, 'Oh, I expect it's the clutch or the brake pedal,' I was able to call out, 'It's the accelerator and well you know it, m'boy!' We tore along at the top speed Hesperus can produce, and when we arrived at the driveway to the Homes, it was to find two cars containing Aldermen just turning in. So we politely waited. And when Mac got into bottom gear to move off in turn, he kangaroo-hopped, and hopped, and hopped. At the sixth hop we were bang slap in the middle of the entrance, and there was a nice little queue of cars behind us in the main road, waiting to get out of the way of the Saturday afternoon traffic. Mac thereupon opened his door, hopped out with his little black briefcase, and said gaily to me, 'Well, you can have the car for an hour. Call for me at 3.30 will you?' and went off. Nice boy, my brother.

I pottered around back streets and country lanes until the hour was up – I left the 'L' plates on to encourage other traffic to be kind to me – when I got back to the War Memorial group of houses. The drive was by now chocked up with bigwigs' cars, and not liking to do a kangaroo hop myself in the strain of the moment, I reversed Hesperus into a side turning off the main road, up a little incline, and in a good position to see over the hedge and across the grounds to the doors of the hall. After a while the bigwigs started coming out, and eventually I saw the Mayor and the Mayoress and the Mace Bearer and the Borough Architect and Mac, all in a little clump. Mac stood at the top of the steps, looked haughtily to the right down the line of cars; looked haughtily down the left row; raised his left arm, bent at the elbow, and looked very hard indeed at his watch. My goodness, here it was half past three and his chauffeur hadn't obeyed his orders. Tut! Tut! This required looking into. All this as plain as dumb show from my seat. I waved vigorously, and at long last His Majesty noticed me, gave a curt nod of the head, turned on his heel and strode manfully back into the hall. And kept me waiting half an hour!! He said there were reporters who wished to ask him some questions.

If, in your long and no doubt ill-spent life, you have come across a fool-proof recipe for taking people down a peg, Mr Bigelow, you might like to pass it on to one who is in bad need of the secret sometimes . . .

Yours very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

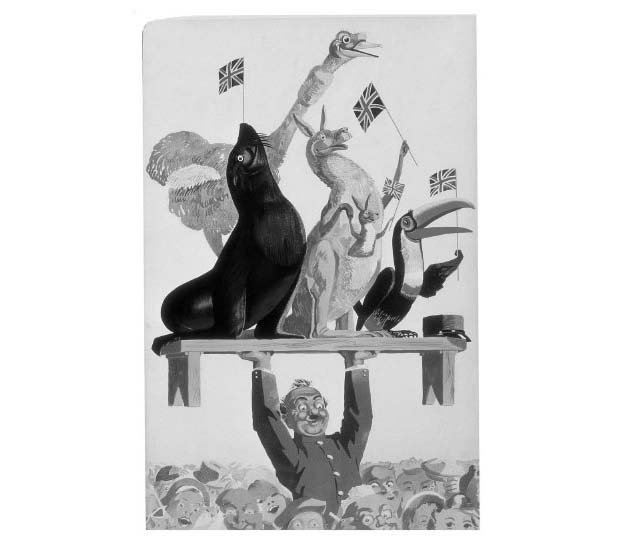

. . . This week has suddenly appeared on the hoardings the wittiest poster I have seen for years. I must tell you that Guinness – the brewers of a sort of beer – run two series of posters. One depicts great feats of strength – a road worker in a hole in the road lifting a steam-roller off the hole in order to reach his free hand out for his glass of beer – and the caption is always 'Guinness Gives You Strength'. The other series shows a chubby little zoo keeper and an animal (an ostrich, lion, toucan etc. the toucan caption was 'If a Guinness is Good For You, Just Think what Toucan Do') and the animal is, or has, swallowed his beer. The caption here is 'My Goodness! My Guinness!' Well, this poster I was describing has nothing on it whatsoever to show what product it is advertising. At the bottom of the poster is a mass of cheerful faces in a crowd. Standing slightly above the crowd is the little zoo keeper, who is holding a bench on his uplifted hands. On the bench are all the animals which appeared in their series of advertisements, and they are all waving little Union Jacks. Everybody, animals and humans, are looking in the same direction. Coming as it has done, the week before the Coronation, I think it the most delectable mixture of the series and the occasion that could possibly be thought of.

We are all decorated and bedecked for Tuesday: the town gardeners have been rushing around taking the dead tulips and wallflowers out of the beds, and yesterday night we bloomed in the dark, for this morning everywhere you look you see great masses of hydrangeas – brilliant pink, bright blue, and white. Or, alternating with them, purple and mauve lupins and pink geraniums. There are baskets of flowers hanging from the lampposts, urns of them along the edges of the pavements; and, of course, the public gardens and the traffic roundabouts are planted and brilliant with them. I bought a little flag to put on Hesperus, but it clicked off in the wind the first time we went out with it, and although we turned the car at the first available side road and went back to look for it, all we found was a group of innocent little children playing on the grass. No flag. Even the most sedate and grand houses, which normally are so sedate and grand and respectable they give an impression of slate-putty colour throughout, have, as it were, undone their stays and burst out of their respectability by putting little blue plaques in windows, reading 'God Save the Queen'. Any stray Americans who may, accidentally on purpose, be in England this week will be very hard put to it indeed to reconcile the goings-on with their previous ideas of the phlegmatic British . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

(reproduced by kind permission of Guinness & Co)

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Tuesday, Monday, and Wednesday this week have between them broken all records ever kept in England for coldness in the month of June. Trust Dame Nature to put her spoke in at such a time. Anyway, I suppose it was a good thing in one way – people didn't pass out with the heat. Instead, they went to hospital suffering from exposure! I read in the papers that about three hundred went, mostly people who had been sitting and lying on cold, wet stone pavements for upwards of forty or fifty hours. Apart from that, there were 'a few' punctures or scratches from bayonets, caused when the marching columns turned sharp corners. I couldn't help wondering whether the punctures or scratched Guard of Honour let out a squeal, or whether they remained stoically 'At Attention' while being punctured. And, on top of that, one man had his foot crushed by a horse and one other man had a leg broken in the crush of the people. Not bad, for so busy and crowded a day. I was alright; I sat in a room about twenty-five feet long by fifteen feet wide, with eleven other people, watching a four inch television screen and nobody got crushed though we all got headaches.

On Monday Mother and I are going to a cinema to see the coloured film of the event, for I believe colour will make all the difference in the world to the scenes. It was difficult, watching the ceremony on a T.V. screen, to realise that it was actually taking place; it seemed more like a film going on slightly shaky but unreal, as a film usually is to me. The Queen's gown did, indeed, look unreal – like soft light shimmering on water, and it made one realise how much is missed in a static photograph of the flashing and scintillation of the embroidery Royalty have on their gowns. I was sure the Queen, poor dear, was over-come when her husband paid homage, for I caught a glimpse, as he backed down the steps, of something white which she was holding to the corner of her eye, and hurriedly put down and tucked in her waistband.

Towards the climax of the Communion, I began to feel most embarrassed, as though I were eavesdropping, or looking through a key-hole. This was due to the fact that all the people at my friends' house were getting hungry, and had started eating their lunches, so the solemn ceremony was accompanied around me by a sort of running commentary of 'Pass the Mustard', or 'Like some more coffee, Connie?' So I was quite glad that the B.B.C. did not televise the height of the service, but showed us, instead, a hanging tapestry in silence for a few minutes, until the service had reached a less intimate point once more.

Of course, Sir Winston Churchill took a plum for himself; he was suitably solemn and emotionally overwhelmed, I thought, in the Abbey, and like a schoolboy on half-holiday in the procession afterwards. As we watched the procession going through Hyde Park, along came nine black coaches, each containing Prime Ministers of parts of the Empire and Commonwealth, and then we heard extra loud cheers and laughter and knew that the tenth contained Sir Winnie. It didn't contain him altogether, for he was hanging half out of the window, his plumed hat tossed aside, making the V-sign for all he was worth and having the time of his young life. London also took the Queen of Tonga, all six foot three of her, to their hearts, and she took us to hers. She refused to have the carriage roof up, in spite of the rain, and went the five miles beaming and waving an arm big enough for Samson of Carnero, and wiping her wet face with an outsize in handkerchiefs.

All in all, it was a memorable day. I did find television non-stop from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m., when I had to leave to come to work, far too long, and I never did find the marching of batches of troops, batch after batch, all that enthralling. But on the whole, it was a magnificent spectacle and we all had a whale of a time.

This is being written on Friday afternoon: I am incarcerated in the Cashier's office. No. 1 Cashier didn't turn up at nine this morning, and No. 2 didn't come in at ten either. In one instance we had a message that her husband was ill (interesting, but not much help to me) in the other we have had grim silence all day. I could spit! To crown it all, my boss couldn't get his figures right in working out the amount of the cheque for the water show producer, and came to me in the cash desk to sort it out. When I gave it back to him I said mildly, 'You and seaside landladies! Try it without adding in the date.' 'What date?' 'You've taken the "y" of Coronation Day as a seven and included it.' He was so mad, and I don't blame him. And now I must stop and get some more work done.

Hope you are well and happy,

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Rosalind's travelling companion wrote me last month, asking me to look for some things she wants to buy (to save time, she says). Their 28 hours in Bournemouth now include; a bathe in the sea; buy an antique sideboard; visit some famous gardens; have luncheon in an old English inn; buy a china animal; buy a 'Scotch golf cap' (whatever that is) and buy a navy cashmere jumper. If we can get a look at Salisbury Cathedral, Corfe Castle, Buckler's Hard and Winchester, all well and good.

Please don't expect anything lucid in today's letter; my mind is chock-a-block with the sizes and shapes of Sheraton sideboards or alternative pieces of furniture; with the whereabouts of that rarity in England, a real cashmere sweater (as opposed to the things we send abroad to people who don't know real cashmere when they see it) or china dogs and horses; and a veritable turmoil of restaurant addresses and possibilities in cases of rain, fog, snow or other seasonable weather changes.

. . . A letter arrived yesterday for Rosalind from, I assume, Mr Akin. There is a pencilled note on the back 'mailed such and such a time'. Does Mr Akin not trust the postal authorities and want Rosalind to com-pare the postmark with his own information to make sure the letter didn't go sculling around the post office for days before they got down to franking it? It will make a pleasant welcome for Rosalind, though (unless maybe she took the front door key with her and the letter is a plaintive plea to return it in a hurry!!!) and I am looking forward to waving it at her from the docks.

I am glad you saw and enjoyed the television of the Coronation. Do try to see the coloured film as well, if it comes anywhere near Bellport, for it is wonderful. It is not very long – about an hour or just over – and it is a joy from one end to the other. My one complaint is that I don't like Sir Laurence Olivier, and therefore felt irritated at his stagey shouting of the commentary, particularly right at the beginning where the royal coach is coming out of the Palace, and he says, in a rising crescendo, '. . . . . . comes to a rising noise of cheers,' whereas the only cheers you can hear then are very feeble and by no means rising. But the colours are so lovely; the people in Hyde Park look like massed pink hydrangeas against soft and misty trees . . . And that unbelievable cloth-of-gold coat which the Queen wears, and the square robe over it for the homage, make the richness of the Bishops and Archbishops look really dowdy, if you can imagine anything doing that.

Seeing the film, I found I was wrong in thinking the Queen wiped her eye as her husband made his homage. The camera in television was behind the Duke, and it did look like a furtive wipe. The cinema camera, however, was on the Queen's right-hand and you distinctly saw the hand push the crown back into position after the clumsy clot of a husband had knocked it skew-whiff!

. . . All for now; I must get my office work finished quickly as I want to get out to lunch early and book my seat on the coach* and collect some shoes from the menders and buy a bright lipstick to rival my yellow jacket.

* Editor's note: Frances was travelling to meet Rosalind at Southampton.

Expect a jubilant letter next week.

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

No rose without a thorn, sang the Victorians. The thorn these last two days has been in the form of a 1934 Ford 8 saloon otherwise known as Hesperus. The rose has been your daughter Rosalind, the loveliest and most delightful heroine Shakespeare wrote of, and so graceful in spirit. And now she has gone on to France and Italy and Mac and I are feeling low and drab. We had so little time to get acquainted and the weather was AWFUL. GHASTLY. DESPERATELY DISMAL. DREARY. WET. VERY WET. COLD. VERY COLD. A colleague, knowing of my plans to pass through as pretty a stretch of country basking in the sun as I could manage (to impress the visitors, of course) said this morning: 'Bit difficult to explain away, wasn't it?' And indeed it was.

Thursday, now, was a very fine day with a brisk breeze and warm sun. We (Hesperus and I that is) picked Rosalind and Mrs Beall up at their hotel and took them home to meet Mother and have a cup of tea. There Mac joined us and we motored through Lyndhurst (where the original Alice in Wonderland lived) and the New Forest to Beaulieu and, we hoped, Buckler's Hard for dinner at the Master Shipbuilder's Hotel. The road from Lyndhurst to Beaulieu reminded Rosalind of the easternmost point of Long Island; rolling land covered in gorse and heather and grass. In Beaulieu we had a puncture and had to prevail upon a farmer (who had been working with only a five-minute break for tea since seven that morning, bless him) who helped him change the wheel. A passing motorist kindly stopped and lent us his brace and bit which fitted. Then they found that the spare wheel valve was leaking, and the Good Samaritan motorist took that one off his own spare and gave it to Mac.

Arriving at Buckler's Hard we found that, being over an hour late, Mine Host had given us up and sold our dinners to four hungry yachts-men who had sailed up Beaulieu river with sea-size appetites. On our saying we didn't in the least mind a cold dinner, he stepped back and allowed us to pass into a very old and charming dining room. The waiter brought, in turn, deep bowls of soup with cream crackers and fresh bread; cold veal and tongue, new potatoes, tiny little carrots steeped in butter, fresh broad beans, crisp lettuce and home-made mayonnaise. To follow we had bottled apricots, ice cream and whipped cream, which he named Manhattan Melba in honour of our guests' accents. After that we retreated to a sort of ante-room to the lounge, where we had coffee and watched the evening descend on the river and reeds at the foot of the garden. It was quite enchanting, and I must say I thought it wasn't bad for a scratch meal!

Yesterday I awoke to find the whole world whipped in flying rain. I called for the ladies at their hotel (and a fine waste of a room looking over the sea it was, too, with weather like that) and when they had finished writing mountains of postcards we went shopping. Rosalind we let loose in an antique shop where she had no end of fun until it was time to rush home for luncheon.

Rosalind herself will no doubt describe the pleasures of Wilton House where the tour was so intimate we felt we had met the Earl and Countess of Pembroke themselves . . . . . . ('Don't fall over the dogs' bowl!' said our guide.) All rooms were filled with family photographs and sweet with the scent of climbing roses. Then we tore back to Salisbury where, alas, we couldn't go in the Cathedral because a service was in progress and there wasn't, anyway, time. Dinner followed in a 1500 inn in Romsey and so, still, in rain, to Southampton where we drove in and out of various docks until we found the right one, and Rosalind and Mrs Beall were hustled hurriedly through Customs, Passport Inspection and all too quickly onto the boat for France.

Mac and I returned, dismally, to home and bed, and today to dreary normality again.

And on that depressing note I will leave you.

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

At last, at last, my brother has passed his driving test. When told the good news, he asked the Examiner if it was 'all right' to drive the car away, and of course, the man said 'No', because the little chit they give you is not a driving certificate, but merely a note authorising the Licensing Department at the Town Hall to issue a driving licence (on payment of the appropriate fee). Mac said he waited until the Examiner had tootled off, and then, to the great interest of a passing policeman, he removed his 'L' plates and drove off to the Town Hall. He there obtained his licence and drove back to his office in the most legal and law-abiding manner, as though he has been keeping within the law all these months!

On Monday morning Mac said to me, 'If you'll go and get the car out, I'll take you down to the office.' . . . As I got into Hesperus's driving seat I touched the steering wheel, and the horn started blowing again non-stop. Mac, frowning like thunder, strolled over and said coldly (it was his bad day, obviously), 'I don't see how you can do it; the car never does that with me!' I pointed out that there was a first time for everything.

But, in truth, it wasn't the first time. It was the third, and all three times had been when I was, alas, driving the thing.

On Sunday I took Mother out for a run, and as I was turning the car on top of a hill the klaxon started blowing. As I hadn't touched it my conscience, pricking slightly, told me that there must be some part of its mechanism at the rear of the car, and I had bumped it in bumping into the grass verge as I reversed. When I went forward again, the horn stopped. We got to within a mile from home quite happily, and were bowling along the main road when the darn thing started again – right bang outside a garage. I swung the car into the garage yard; thought a moment of my financial state (it was the day before payday) and the nine pence which was all I had, and swung her out again. So we sailed along the main road going full blast, with people bellowing at us, staring at us, shouting at us, blowing their horns at us, and laughing at us. Mother was hysterical with laughter, and I was hard put to it to continue driving when we came across a very old man sitting on a bench waiting, I thought, for a bus. As we rounded the corner there he was, leaning forward onto his knees, one hand cupped around his ear. Ah, I said to myself, you'll hear us, alright, Sir, even if you don't hear the bus when it comes. His face was a study as we passed him on our strident way.

On driving into the garage, still klaxing, I discovered – quite accidentally – that when I turned the steering rod to the left, the noise stopped. So I had left it turned that way on the Sunday evening, and on the Monday it was merely the touch of my coat which brought the wrath down on my ears again. Mac very kindly tinkered with it until he got a wire off, so we have run for two days without a horn. Never a dull moment, eh?

. . . Now I must off and away for my lunch. Tomorrow I am taking some friends out in Hesperus for an all-day picnic. If you don't hear from me next week you'll know that something worse than the horn went wrong this time . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

On Monday I was bitten by a dog for the first time in my life, and I don't mind if it is also the last time. A nasty, snappy little Peke with which I was only being sympathetic as it obviously was upset at the rain and the wind. And the wretch bit me. Three fingers of my left hand it got, too. Wait until later in this letter to see if I get rabies, as I am beginning the letter on Tuesday evening, and by Saturday it's bound to show. If you can't wait until the end of the letter, you may peep at the postscript . . .

My heart tells me it is I who am obliged to you, since you

appreciate so kindly the letters I am sending you. And don't you

realise that I find some consolation in writing to you? I assure you

I find much, and I have at least as much pleasure in talking to

you as you have in reading what I say.

I quoted that from the book I am currently reading, with the alteration of only one word: it seemed to me to be most apt for our correspondence; you for ever being appreciative, and me for ever trying to say the debt is mutual. Can you guess who wrote the quoted paragraph? None other than Mme de Sévigné, that Princess of letter writers. And aren't they magic – they almost make me wish to speak and read French, that I might enjoy them in the original.

My mother and her grocer get into mutual difficulties with their respective handwriting; usually, I am called upon by one side or the other, to give a judgement. This week there was some muddle about Mother's order book – she had been given somebody else's by mistake, and couldn't find her own. It was eventually found, and to prove her point that she had never taken it to the grocer, Mother (who couldn't find her spectacles either) asked me to read the last items entered.

Surprisingly, they were fairly clearly written. I read,

'Zulu, Flu, All Set.'

'Yes,' said Mother triumphantly. 'And I haven't had any of them yet!'

As Zulu is the name given to the small black poodle next door, Mac and I are being very careful to investigate all our meat dishes this week. The items, when correctly interpreted (and we went to the grocer to find out, in the end) were: Izal (a disinfectant), Flour, and a box of Liquorice All Sorts. How dismally disappointing is the truth at times!

. . . On Sunday last week I sawed, clawed, tore, broke, or cut about nine inches off the top of our garden hedge, and some six or seven inches off the side of it. This entailed standing on the kitchen stool, which in turn usually means falling face first into the hedge from time to time when the stool hits a soft piece of earth and sinks to one side under my weight. The hedge, now cut down, is still about six feet high and it is very, very hard on the arms and hands to cut the far side of a six foot hedge, standing on a small and inadequate stool. I may say that due to the presence of sundry hen-houses on the far side the top of the hedge has to be cut from our own garden. I didn't count the scratches, but somebody who saw me on Monday thought I had scarlet fever . . . And I thought I was dying, for I hadn't the strength left in my hands to wring out my face flannel on Monday morning! However, I am able to grasp things again by now, which is just as well because Wednesday is payday and wouldn't it be ghastly if I went to the bank and was physically incapable of grasping all that nice new money? . . .

Now if I write any more, the letter will be too heavy for its single stamp, so I won't burden you further until next Saturday.

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

PS Indeed, Sir, and what do you mean – 'Don't miss a mail!' I would have you know, Sir, that I have a secret store of letters in case I fall down and break both arms and can't write for a couple of Saturdays. Fie on you for your lack of faith Mr B.

PPS Was it not fortunate that the dog had many years and no teeth!!

Dear Mr Bigelow,

What I want to know is, who decided I was to be the Belle of the Ball? Not by public acclaim, I am sure; nor was it by private demand that I was awarded the role. No. I am beginning to believe I Have Enemies At Work. And when you have read to the end of this sad story, I think you will agree with me; and, perhaps, you may be able to put your finger on the culprit.

The Ball was officially known as 'Exercise Flash', and was a thing got up by the local Civil Defence crowd in order to make use of a Mobile Column of air-raid defence workers. This Mobile Column is the Home Office's favourite baby at present, and wanders around the countryside demonstrating how efficiently air-raid casualties and troubles can be coped with. The idea is that a certain town (Bournemouth, this week) has been badly bombed and the existing Civil Defence groups in that town cannot adequately cope, so they call on the nearest Mobile Column for help. So everybody works in with everybody else; police, fire-brigade, medical people, air-raid wardens, and the folk who look after what are technically known as 'Enquiring Public' and who feed the homeless and so on. Helped by the Column.

Of course, to make the thing realistic they use smoke bombs and thunderflashes and Very lights and so on. And, to add the final touch, they have 'casualties' for everybody to practise on. I was asked to be a casualty.

That last, simple little sentence, innocuous if ever there was one, was the cause of all the trouble. True, when the person on the telephone asked me he did remark – sort of as an aside, or afterthought – that everybody taking part was insured. That should have told me. That should have stopped me. And if that didn't do as it should, then I should have stopped, backed out, and retired to my safe little home when he added, 'Wear your oldest clothes, tie your head in a bag, and come pre-pared to be dropped.'

Dropped? When that sank in my little mind I decided, optimistically, that it meant I might be dropped by some ham-fisted Home Guard who was holding one handle of the stretcher. Was I worried? No. Well, not much, anyway.

My first appointment was in the Make-Up Room. Here we were togged out in large navy blue dungarees – mine went over a pair of slacks, and a jacket which I was wearing over a warm woollen jumper. You see, I expected to be told to go and lie in a corner out of doors, and it is November and cold and damp, so I had prepared accordingly. Not, it turned out, accurately. We were identified, and given labels to tie on ourselves. I was representing Miss Ponsonby, Matron in charge of the Madeira Road Nursing Home (the police station represented the Nursing Home, and a more depressing and unhygienic nursing home I have never seen) and was said, on the card, to be 21. I have a feeling that the Unknown Enemy put that down as a sop, to soothe me when I Discovered All. The doctor in the First Aid Post, reading my label, remarked that I was very young to be a Matron, but of course he was not to know how brilliantly clever I am.

Anyway, I was Miss Ponsonby and I was suffering from a right arm having been blown off at the elbow, and deep shock.

I was given a small – too small – tweed jacket to put on top of my over-alls and jacket and jumper. The right arm of this jacket had been torn off halfway and was stuffed, with a bit of white and some red sticking out at the end. When, wearing this, I went to the Make-up Table, the officer in charge there seized my false arm and just literally poured something out of a bottle all over it. I dripped 'blood' for nearly half an hour, and can only hope it didn't stain anybody's good clothes. My face was creamed powdered white, and large black rings were put around my eyes (shades of Joan Crawford!) and black was smeared on the lobes of my ears, and replaced my cheerful red lipstick. This was a shock, and a sight of myself in a mirror practically made the make-up unnecessary. The 'best' casualty was a woman who, apart from 'badly gashed forehead, bruised and cut face' was said to have a compound fracture of the arm. To get this, a piece of bone was stuck onto her skin with invisible tape . . . When she came over to the little huddle of 'casualties' who had been made up there were, I must confess, many shudders. Somebody asking what the bone was made of, I carelessly said, 'Oh, I expect it's a bit left over from the last war,' and we nearly had a couple of real casualties on the spot.

Eventually there was a loud 'bang' as somebody let off a thunder-flash, and that was the signal to get us in our positions. I was taken into the police station and into a warren of passages. We twice came up against a barred corridor and felt almost felonious. Eventually we reached a staircase, and went up and up and along and up again and into a large room containing about thirty chairs, some small tables, a piano (flat) and a desk on a dais under the police badge. My guide left me here with instructions to wait until I heard something happening, when I was to switch off the light, barricade the door, and put myself in a suitable position for somebody who had had her arm blown off.

When he had gone, I went around and looked about me, and found that the door was labelled 'blocked by debris, not to be used', and nearly all the windows were marked 'stuck fast by blast, not available'. One window, slightly open, looked onto a small well; and another window, also open, looked out onto the drill-yard where there was a small grandstand for onlookers, reporters, visiting bigwigs and so on. This, I decided glumly, must be the only possible means of exit.

So I chose a spot on the floor which might be less hard than the rest – but wasn't – and I flung myself gently down. After half an hour or eternity, I couldn't tell you which, my left hip went to sleep in great agony. So I got up and prowled about and put my head out of the window to see what was happening. Now Mr Bigelow, a joke's a joke, but what sort of sense of humour can a person have who, immediately on seeing my poor forlorn head, lets off a thunderflash and smoke bomb immediately underneath?

I went back in with such a jerk I nearly gave myself concussion on the window frame. Back, then, to the floor. My third arm – well, half-arm – kept getting in the way, as the jacket was so small the blown-off stump was somewhere near my right back shoulder blade. From time to time the roof of the room was illuminated by blood-red flares, and in their light I could see the smoke curling in and around. Besides, I could smell it; taste it; practically spit it out, it was so thick.