1954

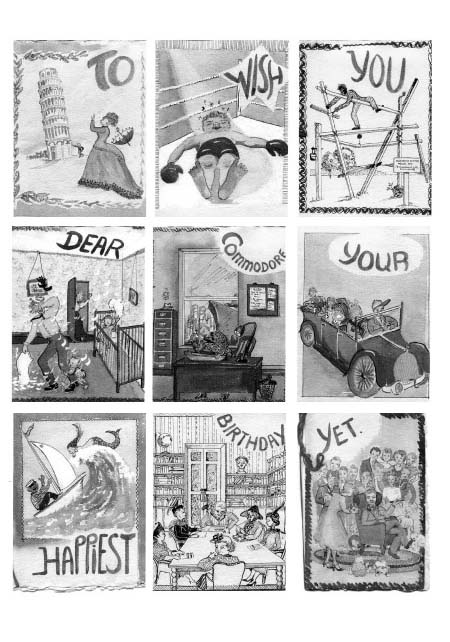

June 12th (p. 177), 'To wish you dear Commodore,

your happiest birthday yet.'

June 12th (p. 177), 'To wish you dear Commodore,

your happiest birthday yet.'

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Alas, here we are once more on our annual pilgrimage to the dentist, losing weight by the pound and sleep by the night. Usually, my 'twice yearly visit' is so dragged out that I turn up each time just as the mimosa tree outside the surgery window is puffed up with yellow flowers. This year, instead of waiting until about May before I plucked up courage, the keen North wind coming suddenly into an open mouth sent me helter-skelter for a telephone and an appointment.

So I arrived at Mr Samson's on Thursday in my usual state of shivers and shakes, and was furious to see a large bowl of mimosa on a marble column in an embrasure in the surgery. I said, indignantly, 'Oh! And I was sure I was early in my visit this year!' and Mr Samson looked so smug I confess I thought he'd had the blossom picked and put there to come fully out in the indoor warmth, just to make me feel the usual cowardly worm I do feel. I felt that way more than ever when the examination was over, and I found that the drilling in one large back tooth was but a preliminary. Now I have to go and see the junior partner on Monday morning ('and be sure and tell him you're to have an injection,' which bodes ill) and have some more drilling on the tooth. Then, on the following Thursday I see Mr S. once more and he'll decide whether or not he can avoid taking out this bad tooth. Three visits for one tooth! I shudder – especially at the idea of, perhaps, finding it hopeless on Monday and taking it out forthwith, for my first-aid exam is Monday evening and an aching jaw is no help at all as an aidemémoire . . .

We read in the papers that you have been having appalling weather lately: I hope you have stayed snug and warm indoors, and not decided to see just how warm the Mercury can remain in below-zero weather. We had a pelting hailstorm, with thunder and lightning and all the stage effects thrown in, two days ago, but since then it has been warm and muggy, though a bit ghusty. I sat and considered that last bit of spelling for some time before I noticed what was wrong with it. Don't you agree with me that a 'ghust' sounds much more windy than a plain 'gust'. After all, the aspirate sounds like a blow: let's reform spelling, shall us? . . .

Last Sunday morning the police telephoned my brother, and the upshot of it was that he had to collect two children from their home, and find them a foster-parent. As it is always awkward moving children and driving the car at the same time, he asked me if I would accompany him. The sudden necessity for moving the children had arisen because on the Saturday night their mother had eloped with the man next door. This left the deserted father with three children to look after (the baby was collected Saturday night, as it was too young for the father to cope with) and the deserted mother next door also with a family – she had four. A total of nine lives upset, and in many instances, changed and made unhappy, because of the selfishness of two adults. Ah well, I am not in a position to judge, and I must say when I met the deserted father I thought him an awful weed . . .

Now I must get this posted. I hope your cold is now quite a memory, and that your recent bad weather has not affected you except by keeping you snugly indoors with the dogs and the cat and The Tin-Opener, Television, and Telephone to keep you in touch with the outside world.

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

The Event of the Week, apart from two trips to the dentist at which he drilled merrily through to my left eardrum on Monday, and my Adam's Apple on Thursday, has been, of course, the First Aid Examination. Listen, and you shall hear about it.

The first-aid lectures – and the examination – are held in a large old house in Bournemouth, sparsely furnished with stretchers, broken-down wooden chairs which fold up unexpectedly, a telephone switchboard and piles of red and grey blankets and grey bandages. These last were once pure snowy white, but have been subjected to long use and misuse by generations of students.

We were herded into what passes normally for the 'staff room'. Here was a small wooden table, a tin trunk, and about six leather-covered seats removed from old motor cars. Not even an out of date copy of Punch to make us feel we were at home, in the dentist's waiting room. Make all except me feel at home, that is, for as you know, the dentist's waiting room is never, never homelike to me. Anyway, we nearly all arrived, as per instructions, at seven o'clock, burping our hastily eaten dinners and biting our fingernails. At twenty past seven an untidy, lumpy figure was seen going down the hall – this was the examining doctor, at the sight of whom sundry groans went up from girls who had met him before. He is apparently one of the school doctors who examine all the children in our free schools (your public schools).

Four men – chosen to be the 'patients' for following students – went to our lecture room. The next four, of which I was one, waited. And waited. And waited. By half past eight our shattered nerves were lying all over the place – you never saw such a sight – and it was almost a relief to get our call. Not, I may say, for very long.

The doctor was, at a guess, Austrian. Rather flabby fleshed, with sparse pale hair turning grey, and thick fat hands to match his thick fat lips, I thought him most unprepossessing. He sorted us out alphabetically, and as I am a 'W', I knew I'd be the last to be examined. But there we were: doctor, table, four students in a row, and behind us lying about on mats and rugs and things, the four male 'patients'. In one corner a St John's Ambulance Brigade lady – our practical instructor – sat rolling up triangular bandages and smiling to herself. No doubt to keep up her spirits.

The first question, mouthed in an effort to make the accent (and the question) completely clear, was, 'Vot are de zigns and zymptoms of a fragture of de loombar region of de zpine?' The first student hadn't the remotest idea. Helped, prodded, hinted and cajoled by the doctor, she decided that the patient would be in great pain and unable to move his head! More than this she could not say. When the doctor, trying hard, said 'Vot abart his legz?' she merely said 'they'd be painful', which was not really meeting the poor man halfway, was it? She had three other questions she answered just about as well. Not altogether giving up hope, the examiner then told her to go and do a 'collar and tie', and a bandage for a broken upper arm. She did the first, and part of the second, but unfortunately she did them both on the same patient. 'Ah well!' said the doctor philosophically, 'I suppose it was my fault – I didn't tell you to use two patients.' So she slunk out of the room, I imagine, though we were so terrified by then we none of us could have turned our heads if Christian Dior himself had been waving free frocks at us from behind our chairs.

Patiently the doctor started on No. 2. Her first question was 'You (you must imagine the accent, I can't keep it up) are going along a road and you come across a man lying in the road, unconscious, and bleeding from the left ear. What do you suspect has happened?' The girl said brightly, 'Oh, I'd suspect he'd had a blow.' A passing carthorse, no doubt – a specially trained carthorse that could kick sideways. Passing rather rapidly – well, after about five minutes hard prodding and equally hard resistance – to the next question, the doctor asked what she would do if she found a man with a broken leg lying unconscious in a room full of gas. She would give artificial respiration. Obviously very pleased with herself.

By this time it had penetrated even through my thick skull that the doctor was a man who wanted first things first. The first thing he want-ed in that question was – 'Get the patient out of the gassy room.' I took heart and resolved to get my answers in their right order. After all, the doctor went out of his way to make us give correct answers: he was extremely kind in that way. Student No. 3 fared no better – she was beginning to get the end of the doctor's tether, and no wonder. He asked her what she would do if she came across somebody, perhaps in a war, who had had their arm blown off at the elbow. Shades of me and the Civil Defence exercise, I thought, and wished I'd had that question, knowing its answer from hard experience. Quite correctly she told him about a rubber bandage. 'And then what?' She racked her brains – you could distinctly hear them racking and said, 'Oh, I'd feel the pulse.' The doctor counted up to a few dozens or so, and I wondered whether he'd say 'Where would the pulse be, in the next building?' but he didn't, he merely sighed and said sadly, 'You would be wrong, young lady. For your future information, there should be no pulse beyond a tourniquet if you put it on correctly.' No. 3 passed out of my ken to do a bandage. That left me, shivering.

'What is shock?' was my first question, and a horrid one to answer, too. I described the zigns und zymptomz, and chattered merrily about 'primary' and 'secondary' shock, 'surgical shock' and so on. (Afterwards I looked it up and found that surgical and secondary are the same thing.) Gently prodded, I found myself bringing out a bit about the causes of shock, and suddenly the doctor and I were merrily engaged in arguing about whether or not it was possible to get into a state of shock when you didn't know what hit you. He gave me a little lecture, and I was (I hope) suitably grateful.

'You find an unconscious person in the road. What do you do?' Well, the book-answer says to start at the head and look for causes of insensibility, and then work your way down the body, both sides. So I started on the head, and five minutes later we were still on that bloomin' head, looking for causes. We had done five different types of fractures on the skull (I knew them, so if you think I didn't let the doctor know I knew them, then you too need your head examined, Mr Bigelow) and eyes and haemorrhage and blood in the skin tissues. In a hurry, I mentioned possible asphyxiation (which should have been first, to be sure, and there I was doing what I had despised the others for doing) and the doctor said sternly, 'You've done First Aid before! Where?' I murmured something about doing a little in my job . . . Now this, Mr B., was a major error in tactics on my part. From there onwards, when-ever I hesitated for a second, he snapped 'Come, come, now – the Matron of the Baths must know!' until I wished I'd said I was a washer-up or a time-watcher or something; anything but what I was . . .

And so thankfully I crept out. I shall pass, I'm quite sure of that, if only out of sheer relief on the doctor's part. I would dearly love to know if all the class gave as stupid a performance as my three fellow sufferers, but really don't think such a thing would be possible. Of the three, two were very young girls who had missed three lectures, which was an excuse for them. And the first was a middle-aged woman who knew everything, at the time of the lectures. Just goes to show – I must remember to emphasise my ignorance in future!

I rushed home intending to have a large brandy to steady what were left of my shattered nerves, and to tell my family, no doubt all agog to hear, what had transpired. The family were playing Scrabble, as to Mother and Mac, and upside down on the sofa asleep, as to Freckleface.

Nobody was a bit interested in my needs for brandy or for an audience. I almost went straight back to the office and wrote you on the spot. Only sheer laziness, and the knowledge that, if I did, I would be left high and dry today with nothing to write about, stopped me. However, now, if you feel yourself going unconscious at any time, just drop me a postcard. I rather hope to be fully qualified to discover the cause . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . My boss is away ill, and so are three of my staff, so perhaps it's just as well the weather is bad, otherwise goodness knows what I should be doing. When Mrs Bond telephoned me to say her husband was ill, I remarked crisply, 'If you don't mind my saying so, Mrs Bond, Sir is an idiot!' When asked why, I told her the silly creature spent 40 minutes out-side the Baths in the snowstorm cleaning his car. When he came in he was, of course, soaking wet (especially his shoes, for as you probably know, the English don't wear rubbers for some unknown reason) and when I attempted to whisk him down with a towel, he exploded. So I left him to go wetly back to his job, and eventually home, where he deservedly caught a bad chill and is now sitting up in bed with his usual little basin, which he fills as regularly as his wife gives him anything to drink – even water, at such times, makes the poor man sick. Men!

Talking of men, I'll tell you about my brother this week, too. Now MacPherson is, let us face it, somewhat spoiled. He had to be indulged in every whim, when he was ill with rheumatic fever as a child, and we've never been able to break him of the habit since. Anyway, one of his habits which infuriates his punctual sister is his inability to be ready on time. Also, his own fury if anybody happens to keep him waiting so much as ten seconds. He isn't the one to do the waiting; on the contrary, everything, and everybody, waits for him. Well, on Thursday the roads were ice, and we sagely decided not to practise skating with the help of Hesperus, and both went out to go by bus to work. I was busy filling the coal scuttles and sweeping the paths, and was a bit pushed for time, so Mother said crossly to my brother to go out to the bus stop and see that it waited for me. I tore out; no bus, no brother either. He had walked the other way to buy some cigarettes. He turned up, and walked beyond the bus stop and down to our garage. Up came the bus, and in we all piled. I dawdled as much as I could, until the bus conductor asked if I was, after all, intending to catch that bus or the next one. On the platform, I caught a glimpse of Mac's face as we went past the end of the driveway to the garage . . . . . . a wonderful mixture of astonishment and fury! The bus wouldn't wait!!! Did the bus know for whom it was supposed to wait? Of course, he was born lucky; he ran to the next bus stop. Normally the bus would have left that point long before the fastest runner would have reached it, but this morning there were so many people there waiting to get on, that Mac arrived before the end of the queue had climbed aboard. Again, any ordinary person running on those icy pavements would have broken at least their spine and seven ribs; but not Mac who, as I said before, was born lucky . . .

I also had a very charming letter this week from Mrs Dall. It was so kind of her to write, wasn't it. Full of praise for somebody she called 'Commodore'. Who on earth could she mean? . . .

This morning, the sun is shining forcefully through my window and baking me as I sit at my typewriting desk. The snow – or rather, the ice – outside is still very conspicuous, but at least some of it melted in the sunshine yesterday. Freckleface was much happier this morning, for the snow on the coal-heap has melted and he was able to scratch on it instead of in the snow. When I left, he was lying upside down on my bed, with his forepaws up in the air and his rear end covered by a blanket, his flank supported by a hot-water bottle, and his little pink mouth slightly open. Ditto, one eye – that being all he feels is necessary. I called Mother and said, 'You can see where Frecks has been digging today, can't you?' He was, apparently, wearing black elbow-length gloves . . .

Thanks for your letters, as always.

Frances W.

Sir,

How dare you! Your letter was read to me yesterday in which you expressed surprise that I didn't like going out in the snow.

My reason for not going out when it is cold and snowy is – I have a gorgeous tail, and if anything happened to it how could I tell the family of slaves who wait upon my every whim, when they displease me? Such logical self-preservation appears beyond a certain 'Angel Face'. How she dares to call herself so, I do not comprehend. Nobody has such an angelic face as your irate correspondent.

Freckleface

Plushbottom

Beau Bully

Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Well, to go from bad to worse. Cars. And brothers. And car-salesmen. And car-salesmen and brothers, in conjunction. I told you letters back, didn't I, that we were negotiating for another car when Hesperus incontinently let us down by collapsing? Well, the other car was a very nice-looking little Standard and the deal was originally only stopped when I, being brought along so that this time I couldn't blame my brother if we bought another pup, said innocently that I personally wouldn't dream of buying a car without so much as hearing the engine run. This pulled everybody up somewhat – it turned out later, we were told, that the car was out of petrol . . .

Isn't this situation – or series of situations – in Egypt comical? It would be, were it not tragic for so many, and serious for so many other nations. Monday everybody is denouncing Neguib* and saying how kind they were not to have him killed. Tuesday he is back, and Wednesday they are all photographed holding hands and smiling like tame gigolos into each other's eyes. Probably the hand-holding is to prevent each other using back-stabbers, but the smiles puzzle me. Unless, perhaps, they are so used to seeing crocodiles in the Nile the politicians automatically adopt the same facial expression . . . . . .

* Editor's note: Mohammed Neguib, Egyptian leader, had deposed King Farouk in 1952, but was himself forced to resign in February 1954 when Colonel Abdel Nassar replaced him.

What with us in Egypt, and you in Puerto Rico, we are having trouble, aren't we? Isn't it horrible to realise one is so unpopular, especially when one tries so hard to do what is best for the other bloke. Couldn't someone in your country suggest that Senator McCarthy (Macarthy, Mcarthy?) is looking the wrong way and should turn his eyes away from the Army for a bit, and down to the Caribbean . . .

A miracle happened on Monday, Mr Bigelow. I was sitting reading the paper by the fire after dinner, and my brother, who was later home than me was eating his dinner, when suddenly he said, 'Norah.' I said 'Um?' and my astounded ears heard his voice saying, 'I realise it was entirely my fault, and I do appreciate your not throwing it in my face that I bought the Ford . . . . . . !!!!!' The upshot was, that he intends paying the difference between what (we hope) we get for the Ford and what another car costs, if I in turn will pay for the car tax and the insurance. As this would save me anything up to £12 or £15, you can imagine I was far from displeased! I am, however, woman-like, intrigued to discover where Mac has suddenly acquired all this money, because he was flat broke directly after Christmas and all through January, and his job certainly doesn't pay him all that much cash. However, no doubt if I sit tight and ask no questions, I shall hear in due course . . .

Advertisement in last night's local newspaper: '1933 Singer 8 for sale. Runs like its namesake. Brakes squeak more than prodded politicians. Clutch fierce as a Sergeant-Major. Better downhill than up. Got £39 to spare? Phone Wareham 54.'

And that's all for now. Be with you again next Saturday.

Very sincerely,

Frances

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Short of arsenic, what can be done with my brother?

You remember my interim report on Hesperus? Well, that was sent on Wednesday morning. That evening Mac and I dolled ourselves up in overalls and old gloves and things and went to work again. We finished the first coat of cellulose, and had time to do the second coat on the bonnet (the first having been put on there a day or two earlier). About eight o'clock, not being able to see any more, we came home and scrubbed most of the skin and some of the cellulose off ourselves. Mac said he was going out – and did, by way of the back door which leads to the shed in which he keeps his bicycle.

Next morning it was wet, so I rose early and dressed in a hurry and tore over to put some wax polish on the finished bonnet of the car, so that it would not suffer in the rain. To find that the paint was spotted all over with wet drops and that, as fast as I wiped the paintwork with a dry cloth, so the paint came off along with the water. My brother had only taken it straight out – in the rain – the night before, within half an hour of the paint being put on! Now he is sulking in an injured innocence fashion because, when he asked when I was going to help finish the painting I replied that I wasn't. Sometimes I wonder why God made men; given a tiny bit of common sense I'm sure He could have so arranged matters as to make them redundant.

Oh – I collected my Civil Defence Ambulance Section uniform last night. Look absolutely smashing in it. Only thing is, I can't move. The blouse-top fits around me, and so do the trousers, but they meet only with the greatest difficulty, and at the slightest movement on my part there appears a wide strip of me around the middle. The only thing I can think of to do about it is to wear a bright cummerbund, which should cheer up the Civil Defence Unit considerably. The material is a very dark grey thick heavy stuff, and so scratchy I was advised to wear stockings under the trousers and can see myself being their first genuine casualty – a bad case of the itch!

I have been on a sort of semi-diet this week: instead of having a scrambled egg – one – for my midday meal, I am having fruit. Keeping off sugar and sweets and cakes and biscuits, but enjoying a hearty meal in the evening, as usual. The result is that my measurements seem much the same, but my weight has gone down 6lbs since the beginning of the month, when I started by cutting out sugar. Now isn't that just too bad? What's the good of losing weight if you don't lose size as well – one might as well be H. G. Wells's character, who lost weight and ended up crawling around under the ceiling, he was so light, and still looking like a bloated slug, he was so fat. So far as I can see, the only result of this careful eating is that I feel d-mn hungry!

. . . How very disappointing for you and Rosalind to drive all that way to look at the late Theodore Roosevelt's old home, and then find it closed! I know the feeling . . . . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . We, Mac and I, discussed the advertisement for Hesperus this week. Mac wanted to know whether I thought '£75 or near offer', or '£70' would be better. I said as we would be delighted with £65 I thought the latter was more likely to attract buyers. It was agreed that '£70' would appear. So Mac puts in an advertisement saying '£80. Nobody has nibbled!! . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . One afternoon over Easter weekend, when I wasn't working, Mac and I walked to Wimborne with a friend. How the friend manages it I have never discovered; she cycles to work each day, and her work is sedentary, but at weekends she thinks nothing at all of a 15-mile walk in an afternoon. Now Mac and I think nothing at all of a 15-mile walk in an afternoon, but we aren't thinking on quite the same lines. Wimborne is about eight miles from home. We had walked one mile, in single file (all there was room for) along the pavement, with a bumper-to-bumper stream of cars running alongside, when I revolted and refused to do so any more. So there we waited for a bus which took us another mile or so along the route, to a point at which we could leave the road and do the rest of the walk through green fields and pastures new – to Mac, anyway – and under lovely budding chestnuts and alongside large black and white cows. Also, alongside a river for part of the way. Very pleasant, with the sun strong and the wind blowing half a gale in our faces.

'Never mind the wind,' said the friend, 'it'll be at our backs on the way home.' I looked back at Mac's face, and what I saw made me giggle. Dorothy asked why I was laughing but if she were as stupid as all that I wouldn't be bothered to tell her!

In the end we reached Wimborne, and found there was fifty minutes or more to go before the first bus back. We sat for a while on a bench in the village square, only I was sitting next to one of the oldest inhabitants and he was making a valiant effort to win the world's spitting contest, so I soon gave up the unequal struggle between my tiredness and my nausea, and went and stood at the bus stop, first on one leg and then on t'other. Dorothy, apart from being cross at losing half her walk, was also annoyed because both Mac and I complained our backs were broken in the lumbar region! According to her, a little eight-mile stroll would put all that right.

And now, of course, you are waiting to hear about The Pippin. This friend asked, while we were walking, whether I had thought of a name for the new car, and on my saying yes, I had, Mac put on a long face and said pompously, 'It was all very well naming Hesperus, and I realise that it was a suitable name, but there is no need to give a nickname to a car which is not a wreck.' I said meekly that I thought of calling it 'The Pippin', and the little face lighted up like a Christmas tree candle!

Anyway, as I expected, he came motoring round to my office yesterday – yes, we only finally got the thing on Friday, and even now it has to go back for two lines to be painted on the body – at midday, unable to wait until five to show me the car. I went out to see it, Mac's face being all screwed up with anxiety until he noticed how pleased I was with the Austin. It really is a very nice little car indeed, and looks as though it's just come, not off the assembly line, but off the workbench where it has been made by hand. When I tell you that the clock goes, you will realise it must have been very carefully looked after in its life. As we walked around it admiring and exclaiming Mac suddenly exclaimed a bit louder than usual, and ran back to the other side of the car. He then clapped one hand to his forehead and said a few rude words. Apparently he had taken somebody out before he came to me, and while they were bowling along there was a loud noise, which obviously couldn't have been the car after its long and arduous going-over by the car dealers. But it was! And we are now minus one chromium-plated wheel hub . . . . . . typical of our motoring experience, what?

Now to finish off: I hope this reaches you before Thursday, so that you won't think I've gone down the drain. Never think that – if I were flat on my back with double pneumonia and three broken arms, I'd drop you a postcard with the pen held between my toes, whenever Saturday came round . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances

Dear Mr Bigelow,

When patience runs out, manners are a very thin veneer indeed. Or so I have found this week, under somewhat trying circumstances, and goodness knows how soon (it's Wednesday now) it will be that the veneer will crack.

For on Tuesday, as I ushered a traveller out of my office, from around the corner came another figure – it was Dr Russell from Canada, who announced that he had arrived and was come to live permanently in England. Well, so long as he lives well away from Bournemouth, I don't mind where he lives for, as I hinted above, I long ago ran out of patience with him.

In the meantime, he has been hanging around either at the office or at home, and behaving in his usual manner, with, as I said, a resultant strain on my politeness. After all, if within a space of four hours you were to say eight times to me, 'Were you surprised to see me?' – and that remark was usually pushed bang in the middle of a sentence somebody else was saying, wouldn't you rather expect the person of whom the question was asked to start giving you variations of answers, just to make a change? After a silence lasting five years, Dr Russell cannot realistically expect me to take up exactly where I left off (and I'm sure he would not like it, for I remember being very angry with him last time he was over here) but, just the same, the minute he manoeuvres me alone, he starts looking soulful and saying 'Nori, what's wrong? What's the matter?' Well, Mr Bigelow, my private opinions and my soul are my own, and I will not discuss them at the whim or the insistence of any questioner in the world, if I don't feel so inclined . . .

Anyway, finally we had a sort of a row, which I thought did little good at the time, but apparently it was borne in on that man that his presence was not as overwhelmingly welcome as he imagined it would be, and on Friday he rang up and said he thought it a good idea to push off to London. I said I thought it was a good idea, too, and goodbye and there we were. He also telephoned Mother and asked what was wrong with me. Mother, flying to the defence of her chick, said there was nothing wrong with me. So Russ said well, what had he done? And Mother, being quite his equal, retorted it was less what he had done and more what he had not done, and wasn't it time he realised one had to work to earn people's friendships, or to deserve them.

He is now out of my hair, off my conscience – except that I don't like to think of him going off all hurt and huffy – and once more I am breathing normally and looking normal, too! On Wednesday, knowing I was faced with a tête-à-tête all evening I was so sick with apprehension that the staff started asking what was wrong. It's no good trying to continue a broken friendship with somebody who affects one so heavily, and I don't believe anybody has the right to inflict his emotionalism on other people to the extent that Dr Russell tries it. He wears out every-body around him, and then sails on to wear out somebody else. Well, he can sail as far on as he wishes . . .

Now I must get back to work: my boss is away this weekend so naturally everything has gone wrong, and I've even had the police in and out of my hair these last two days over an unpleasant event I reported which would have to happen when the boss is away. Eight years I've been here, but it waits for his absence! Just like events.

So au revoir until next Saturday.

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

How very unlike yourself you sounded in the letter I had yesterday: I hurry to send you an 'extra' to tell you to cheer up. All sorts of things are worth doing, so you get that negative idea out of your noodle. It's well worth sitting in an easy chair with a cat on your knee; it's well worth watching birds; it's well worth eating a good meal; it's well worth watching the seasons change. It's well worth writing to me. It is well worth looking forward to Rosalind's visits, and then looking back at them until it is time for forward-looking again.

Really, Mr B. I am surprised at you! Kindly refrain from such pessimistic perambulations in future.

Anyway, on its way to you, and due to arrive in a few days after this letter, is a funny book I thought you would like to read. Called Doctor in the House it has recently been made into a very amusing film, though that isn't as funny (in my view) as the book. Perhaps, if it arrives before Rosalind, you can chuckle over it together.

I was trying, as tactfully as I know, to suggest to my apprentice-boy that he should take lessons in English, the other day. Or, failing evening classes, he should read and read and read – good books – in order that his written English might become improved by precept. Reading will do it, but it is a long way round. Anyway, he affirmed that he did read, 'Honest, Miss Woodsford, I get a book out of the library every week, and I read everything that Kipling writes.' I was delighted to hear it, and asked which book he liked best – Soldiers Three, or Plain Tales from the Hills, or perhaps Stalky & Co. By this time it became obvious from the blank face a foot or so above mine, that Peter didn't have the slightest inkling what I was talking about. So I stopped my catalogue, and said, 'You did say Kipling, didn't you?' 'Yes, Kipling – you know, the man who does the butterfly stroke.' Education, where is your aim? In the meantime I get little notes from Peter, 'Mr Brown wonts for towle. Can he hav them?'

You didn't mention in your letter exactly when Rosalind was likely to visit you . . . I may write Rosalind myself tomorrow or Friday if there is time but anyway I hope you both enjoy yourselves terrifically, and don't you start worrying because you 'can't do much for her'. I'm quite, quite sure Rosalind is absolutely content to stay Chez Bigelow when she visits you, and am certain she doesn't always want to go dashing around here and there, having parties in all directions, and fetes and fireworks and so on. A nice cuppa tea and me feet up, is some people's idea of Heaven, and I'm positive that at times it is equally Rosalind's ideal, and one you can easily supply. Cheer up. And stay cheered. Them's orders, Sir.

Frances W.

PS Thanks for the sketch of Angel Face. I would know her anywhere!

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . What a lot of fuss everybody has made over Roger Bannister! Personally, I had never heard of the mile-in-four-minutes before he did it in less . . .

Sir Bertrand telephoned me last night: I was just about to go out, so didn't hang on talking long and got him off the line when the three-pips (to indicate three minutes) came along. He giggled a good bit, but apart from telling me his new address, and where he had been staying and what doing ('Have you got over your dismay, Nori?' was every other sentence but I ignored that and merely answered the alternate ones) he wasn't too much of a nuisance. I had an idea he rang when he did to get invited down for the weekend, but I didn't bite, having things to do. As he has been staying in an hotel, and is moving to another soon, I imagine he hasn't got invited to stay or live with any of his London friends. Poor Sir Bertrand! Shouldn't be such a bore, should he? . . .

In the paper this week, reported from Australia: The Queen and the Duke watched a log-chopping contest, and afterwards the Queen said to the winner, 'You must be so fit!' 'My oath,' replied the burly Aussie, 'I could lift a bl—dy ton!' 'Here,' protested the Duke, 'tone it down a bit.' 'Well,' said the Australian, 'I could lift a bl—dy half-ton, then.'

And that's all for now. I hope you have had Rosalind to visit you, and enjoyed every minute (as I know you would) and are now counting days to the next visit.

Very sincerely,

Frances

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . On Thursday this week, as it was a more or less fine evening, the Civil Defence class was held out of doors. More or less out of doors. The two instructors put the casualties in a specially built 'bombed house' in a field, and then the three competing teams had in turn to rescue and attend to them. The house has two downstairs rooms, one of which has the ceiling down, and half a staircase with newel post and other posts in the most awkward positions, as we found to our cost. There is no roof or upper storey, and the sky appears in unexpected quarters. It was a very heavy evening, with millions of flies and gnats about, and we made 'phewing' noises at the smell of pigs nearby until somebody remarked that it wasn't pigs, but that the town's Sewage Disposal Farm was just across the hedge. After that, we all dashed into the long grass and picked clover to hold under our noses, in spite of the remark a Town Hall man made that there is less sickness in the Farm staff than at the Town Hall.

Now after Thursday, Mr Bigelow, I am of the firm opinion that dragging 'unconscious' bodies about on stretchers, over and under and around bomb-damaged houses, is no job for women. Next Thursday I shall either be a victim myself, or sit on a chair and look on, for I am quite certain my muscles will not, by next Thursday, have grown back onto the bones from which they were wrenched last Thursday.

I don't know which team won, but we didn't do very well from all I could see – I was Ambulance Attendant, which meant I was sent with the driver to fetch the ambulance, run it up to the nearest point to the house; prepare the stretchers with blankets, bring them into the building, load the patients on, take them out, put them in the ambulance, and drive them off to the 'hospital' ten yards down the lane. When I got into the room with the first stretcher, my team were milling around the first patient who was sitting with a complicated fracture of the ribs. I con-soled myself later, when I saw Team B tip her off the stretcher into the road (accidentally) and Team C with the fracture on the left side and the bandages on the right side.

On Wednesday, I had a refresher lesson on the ambulance, driving up and down side roads at enormous speeds (for me) and reversing into gravel pits by use of rearview mirrors only.

At that, I was extremely bad, but hope to be better next week. I was surprised to find how easy a large and powerful vehicle is to drive: it could be turned in a normally wide road in three goes, quite easily – a lot more easily than the Austin which is only half the size of an ambulance. By now, my motoring experience consists of:

1 ancient Ford 8 hp. wreck

1 fairly ancient Singer 9 hp. car

1 fairly new Hillman Minx, 10 hp.

1 oldish Austin 10

1 32 hp. Buick ambulance

1 32 hp. Packard"

Next lesson, a double-decker bus, yes?

At work, we are in the throes of rehearsals for the summer show, due to open on Friday next. The consumption of indigestion tablets is reaching wholesale figures. I am getting new frowns of worry, trying to decide whether to ask the Mayoress to have a drink before I ask the Mayor, as she is the lady: or whether the Mayor comes first, as the Head Man in the town for the year. My boss stays well behind the scenes, seeing that the chorus girls are on time and so on, and leaves the gracious hostess work to me, all dolled up in black satin, new shoes, and a harassed look. I shall no doubt moan about this next week . . .

I will say 'au revoir' until next Saturday, and I hope you had a lovely visit from Rosalind, who was looking forward to it as much as you, and as equally sorry it had to be so short.

Very sincerely,

Frances

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Friday, worked until 10 p.m., rushed home and did my week's washing, so that today, Saturday, I can set off for my summer holiday with a clear conscience. As the 'holiday' consists of three and a half days during which I have to do all the car-driving and Dorothy, who is going with me, is likely to refuse to do anything to help (such as paying the bills and seeing to tips, reading the maps and so on) I can imagine my return Tuesday night will see me rather tired . . . Today, Saturday, the skies are lead and about ten feet overhead, letting out gallons of water in a solid sheet. Just the weather for motoring or walking. Just my luck.

And talking of my luck, I'm beginning to feel confirmed in my belief that I have a jinx. You remember in my last letter I said I was bewildered, bothered, and very, very depressed, and if you were right and Rosalind wrong, I would be even more so. This morning, on top of the weather, was a letter from Rosalind, in which she quite calmly confirmed the newspaper cutting Mrs Dall sent me last week, wherein you were reported as saying proudly that you were '91, just getting going'. Now I wouldn't mind if you were 101, personally, but for one thing. In two letters I had from Rosalind in 1948 (December) and 1949 (Jan.) she mentioned her father (84) whom she was about to visit, or had just returned from visiting. After I had written to you for some time I looked up these early letters, to confirm whether it really was possible that any-body as spry in his writing could really be 84 or 85, or whatever it was by then. I made a note in my diary, and each year since have brought it forward so that I would know, well in advance, when you were due to be 90. According to Rosalind's early information, this great day was to be in 1954, in September. Since early January I have been preparing for the event. Since early January I have been taking trips to the Reference Library, and spending my lunch hours in my office with scratch pad, drawing paper, pen ink paint and brushes. All those elaborate questions I asked you were only to one end – to discover the difference in cost of a letter being sent locally, and being sent to England, so that I could send Mrs Dall enough money to pay her for the stamps she was to use. For she, poor dear, was to be dragged in, as the 'surprise' was to be in nine parts, and each part was to be posted separately, so that the first came ten days before your birthday, and the final one on the day itself. That was why I wanted to know if you had a mail delivery on a Sunday, remember? I even spent an hour or so looking up an impossible word in a rhyming dictionary, knowing your fondness for long and unusual terms . . . . . . you try to find easy rhymes for Ninety.

And now it turns out you are 91. Or, anyway, will be on your next birthday. I might just as well send you theatre tickets for a show which closed last week, as to send you my 'surprise' now. But in order not to waste entirely the time and trouble, I have done the whole wretched lot up in a bundle, and posted it off to you today, and will you please just imagine you are celebrating your ninetieth birthday last September and I'm just a day or two late, due to circumstances over which I have no control. If Mrs Dall hadn't been kind and sent me that newspaper cutting I might never have known I was too late. As usual, my good intentions go wildly astray. Do you think I should decide just to be selfish and let everybody else go hang, so that perhaps, by my usual contrary luck, I might hit the bullseye by accident? A thing I have, of late, never, never managed to do by design. Do you mind letting me know in plenty of time – say at least ten months beforehand – when you intend being a hundred? I am determined to be on time one year or another, but 91 is such an in-between age, it fails to inspire me one little bit. Oh, damn my bad luck!

On which heartfelt note I will leave you and go dashing out in the downpour (matching my mood) to post this. I hope to sound a little more cheerful by next Saturday, even if tired.

Very sincerely and down-in-the-dumps,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Oh dear, I am sorry about the Adventures of A. Marsh. The Telegraph critic referred to it as a full-blooded masterpiece, but I didn't have any idea it was bl—dy as well! Writers these days seem to think that as so much has already been written, there is only left for them those subjects hither to be discussed only in medical books. Anyway, I am awfully sorry to have inflicted this one on you. I hope it hasn't irredeemably damaged your gay innocence!

And oh dear, again, that Sir Bertrand is here once more. Fortunately, this time he only came down for the day, so as I refused to take time off work (not having known he was coming) I had him only from 5 p.m. until his train left at eight. Now he has progressed to the stage where he remarks lugubriously that he has 'had time to have a look at himself, and doesn't like what he sees' but perks up to say there is 'always Seconal'. Or whatever the thing is called – a sleeping drug people are apt to commit suicide with, I believe. I told the silly thing to stop crying in his beer; if, as he said, he was of so little importance, then he was too unimportant to ruin good beer. I think Dr Russell should have been born Dr Russelsky, with his Russian love of misery and emotion, don't you?

Admittedly I do feel sorry for the poor man, for he's been in England only about a month, and already his bad lung is giving him trouble, so he has to go back to America. He is aiming at California, which is the sensible thing for him to do and the thing I've been advocating ever since 1946 . . .

What with Sir Bertrand threatening suicide on Wednesday; a woman customer considering herself 'insulted' because the bath-attendant put her in a bathroom on the right-hand side of the corridor instead of the left-hand side which she preferred; and a man complaining bitterly that he didn't like the way a male attendant looked at him – and my boss shouting abuse at me because I hadn't told either customer I thought they were cranks, well, not in so many words! – and Mother ringing up in the middle of all this to complain that the expensive Hoover I had bought her the day before wouldn't work, I am back in my old slough of despond with a vengeance. So I was rather silent with my miseries in the car this morning, and Mac was as funny as Danny Kaye, trying to get the normal chatter out of me. And Mother at lunchtime was going around with her 'sorry I spoke' attitude. How we do affect one another with our moods! I can quite understand why Russ rushes to me when he can, for a good blowing up, or advice or sympathy, for my own family do just the same. Never mind what calamity overcomes them – they'll just 'ring Norah and tell her; she'll do something about it!' Oh yes – on top of all those horrors I described at such heart-rending length in this paragraph, I finished up my Awful Yesterday having a lady pass out with (query) heart trouble during the water show, and I had to get an ambulance for her. Afterwards, I had to rinse out the towels and blankets I had wrapped her in, because by the time I had run downstairs, across the hall, up the other side, into the café, around the counter, to the sink, and run back all that way with a basin for the patient to be sick in – it was too late! I didn't dare let them stay overnight, for the boss might have found out, and as his idea of First Aid is to get the victim out of the building and his jurisdiction as quickly as possible, he would have been furious at having our towels and blankets used for such a purpose.

With such sharply divergent outlooks, it is odd that Mr Bond and I have managed to work alongside each other for so many years, isn't it? . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . My favourite police inspector came in this morning with a reasonable excuse for his visit and a bit of grit in his eye! I think he went out a very disappointed man. No little-womanly gesture with a bit of lace-trimmed hankie was forthcoming. No lace. Instead, I handed him an eye bath and a towel to weep into, neither of which can reasonably be said to come under the heading 'the woman's touch'. I never indulge in little-womanly gestures unless I am quite sure they'll come off, and as I know grit is extremely difficult to get out of an eye, the poor man was forced to roll his around on his own. My own eyes, today, feel as though the lids were literally lined with emery paper, due to a series of bad nights. Why don't people sleep? One of life's major mysteries; along with my favourite, Why Do Acorns Grow into Oak Trees and not Poplars, and the one about who started the common cold . . .

On Sunday afternoon last weekend I took Mother to Durdle Door in Dorset. This is an enormous block of rock jutting out from the main edge of the coast, in the last bit of which is a natural arch of rock – the Door – famous in this part of the world for its beauty. Of course, this being our first visit we must needs find the beaches strewn with hundreds of people from a nearby camp – as if I didn't have enough people at work! There were four or five perfect curved beaches, and as we sat halfway down the cliffs we could look down at their waters and watch the changing colours as the sun came and went. When it was out, the water was purple and deep emerald and peacock blue; when the sun went behind a cloud, then the water was blue-grey and brown. The cliffs here are white, grey, or sometimes streaked with vivid red, and we could see them stretching their heads towards the south for miles in both directions. To the west, we could see Portland Bill – the dark prison on its heights looking quite pleasant in the sun – and three aircraft carriers at anchor in Weymouth Harbour. To the east, the sun shone on the Needles at the western end of the Isle of Wight. I suppose this would mean a stretch of view extending some fifty miles with us in the middle. It was an unusually clear day (portending more rain, of course) and we don't usually get so long a view, but we enjoyed it while we did.

As a contrast to this noisy scene of people enjoying themselves, we stopped the car for tea on the topmost point of the Heath which is used by the Army for training tank crews. And if you don't know what tanks do to countryside, don't try to find out for it's too depressing. Miles and miles of black and brown earth, with here and there a stunted, scarred little tree or a bit of heather. Talk about blasted heaths! It is part of that heath made famous by Hardy under the name 'Egdon Heath', and it explains amply and without words why his books are so depressing. They merely reflect their surroundings. Parts of Dorset are extremely lovely – the hills towards Devon, and the northern part of the county where it nears Wiltshire or Somerset; but that small area which Hardy wrote about is almost without exception an indifferent countryside. Many people have written of this facet of its character: it is a country age-old – long, long before the Romans or even the Druids, and it is filled to overflowing with burial grounds and ancient earthworks and so on. The earth has been lived on so long it has become quite indifferent to what human beings care to do to it; it just goes on and they don't. It gives me the shivers.

This appalling summer is making us break all records for attendances in every department at work. A side-result of this is that people keep walking in and out of my office smoking big cigars, and as today (Saturday) I have a smashing headache, they are not being very well received. Neither have I the self-control left, what with headaches and sick feelings from too many aspirins and more nausea from cigar smoke, to polish a nice final paragraph for you. Will you please rest content, this week, with my felicitations,

Frances Woodsford

Dear Mr Bigelow,

It was just as well the police held their annual swimming gala here this week because they always give me a large drink during the course of it and this week I needed it, having just returned from mailing your birthday card at the post office. Talk about profiteering! Why, for another seven or eightpence I could have bought you the Brooklyn Bridge for a present, and on that there would have been no extortionate postage, as it is already there, in place, ready for you to cross next time you go into New York to do some town-painting. Anyway, flummoxes notwithstanding, I hope the card arrived on the right day, and hope the birthday went off very well indeed, with Rosalind's presence in spirit adding to the occasion . . .

It was just as well, to repeat my opening sentence, that the police were holding their gala here this week, when they gave me that large drink, because it was such a very large one I felt relieved, as I motored home directly afterwards, that most of the cops in the town weren't out looking for weaving motorists. And all I asked for was an orange-and-soda, as I was thirsty! They pooh-poohed the idea, and insisted I should have gin with it. Now, I hate gin, so I refused indignantly, and we com-promised on 'a drop of whisky'. I suppose a drop can mean many things, from a single globule of water to being hanged by the neck, but this drop of whisky was about halfway between the two. Fortunately, the full effect did not hit me until I climbed out of the car in the garage, but it took most of the night before I could get to sleep for flashing lights in front of my shut eyes. Liver? No, no, of course not – what a nasty mind you have, Commodore. It was over-tiredness, and over-excitement that did it. If only I had seven pairs of hands and three sets of brains, I could work the front-of-house part of the police gala with ease. One pair of hands could be counting out money for the stewards to use as change; the second could be making a note of where I'd borrowed the money from; the third could be opening drawers looking for last-minute requirements such as chalk, string, paper and pins. Pair No. 4 could be counting out programmes, chocolates, cigarettes, ice creams and matches, for the usherettes to take around, while No. 5 could be making unhurried notes of the value of all these issued. No. 6 could be using the telephone to ring up various expected parties who hadn't arrived, but whose seats were being held in the teeth of great competition from the general public. And No. 7 could be articulating graciously to the Important Guests who will always arrive when I am tying up somebody who has just fallen downstairs, coping with a man complaining that he can't get his favourite brand of cigarettes, sudden requests for 'change for a £5 note, please' and trying to stop my stocking from laddering where I caught it on the door as I rushed through just now. I think three brains could properly co-ordinate and control seven sets of hands, and if Mr Bond had only complied with my request, the Police Gala-before-the-last-one, and given me roller skates for Christmas instead of bath towels, then the seven sets of hands could get to their various jobs so much quicker than my flat feet take them . . .

Very sincerely yours,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Something very nice happened to me yesterday. A letter came by hand for my boss; he opened and read it, then handed it to me to read the last paragraph. I will quote it:

I am enclosing a cheque for two guineas made payable to you and I would be obliged if you will share it among your staff after one guinea has been given to Miss Woodsford with our special thanks for the help she gave us. I know for a fact that paints are expensive and that she will find it useful.

Now, wasn't that kind? I felt a bit conscience-stricken, and it took some persuading on the part of Mr Bond to get me to take the money, because I had scolded the man who sent it, when he told me he was going to send that amount for the staff. I told him – it was my favourite police inspector of course, he's the only one running a gala here who ever bothers to say thank you –- that he always overpaid the staff. That we were always glad to help the police, partly because they ran their gala so efficiently, and partly because they always took the trouble to say ta ever so, and we all appreciated that no end. And the only result of my lecture is, as you will see, that I get half the swag myself! I didn't scold him with that end in view at all, so perhaps as I am enjoying the fruits it is only right and proper that my conscience should prick as I eat. Anyway, having the money (a guinea is a very polite £1. You pay a tradesman in pounds, a gentleman in guineas. Don't ask me why) I went out straight away and spent it on oil-paints and a lovely big palette before my conscience could think of another excuse (shoe repairs) for pricking . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

For somebody who didn't 'know the date' you have done remarkably well, I must say. Today, the postman arrived with two boxes of chocolate liqueurs! And today we are having a specially good dinner, which will follow up with chocolate liqueurs all round (my choice will be the Grand Marnier) and a sip of Drambuie to make us all feel very content with the goodness of life . . .

Phyllis Murray and I came back from holiday a day earlier than arranged. On Phyl's part, she had run out of money. On mine, I didn't like to suggest staying longer and paying for us both, as she is most independent (I'd got away with twice filling the petrol tank) and the car wasn't going very well . . . By a mistaken interest in a place charmingly called 'Wellcome' we went down a 1 in 4 incline on our last day, and I was wondering who was going to push us up, but we managed it. We had a very fine day for the run home, and to my horror I discovered when I reached Bournemouth that I had driven 170 miles practically non-stop. Anyway, it was a good thing to do, for now I know that the maximum day (140-odd) planned for Rosalind's tour next June will be easy. Mother was desperately worried all day, for we were motoring over Dartmoor and a very dangerous criminal escaped from the Prison on the Moor and was at large all day. We came blissfully over, ignorant as anything, not having seen a newspaper for three days, and we couldn't imagine why the police stopped us in Honiton and looked in the car . . .

Now back at work, and it's still pouring with rain but at least we can change wet clothes. Coming home from Devonshire, I wore my brother's ancient coat normally used to cover the car bonnet on cold nights, and Phyllis wore all the jumpers and skirts she had plus my plastic raincoat. Never mind, it was a pleasant change and we came home revived mentally and spiritually if not physically.

Once again, thank you very much indeed for the lovely liqueurs, and for being so exceedingly clever over the date. Did you cheat and ask Rosalind, by any chance?

Very sincerely,

Frances W.