1956

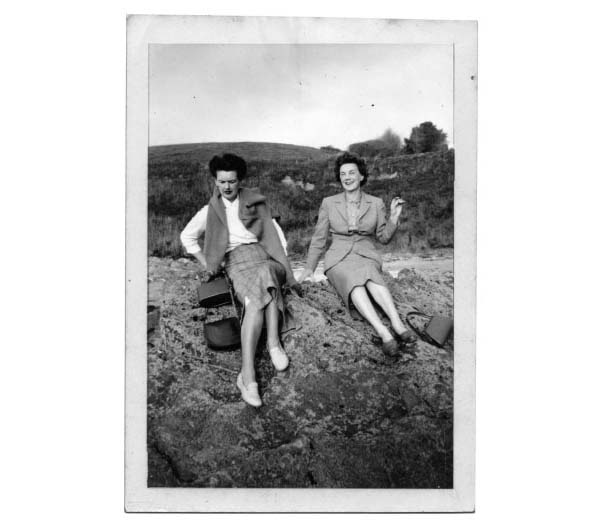

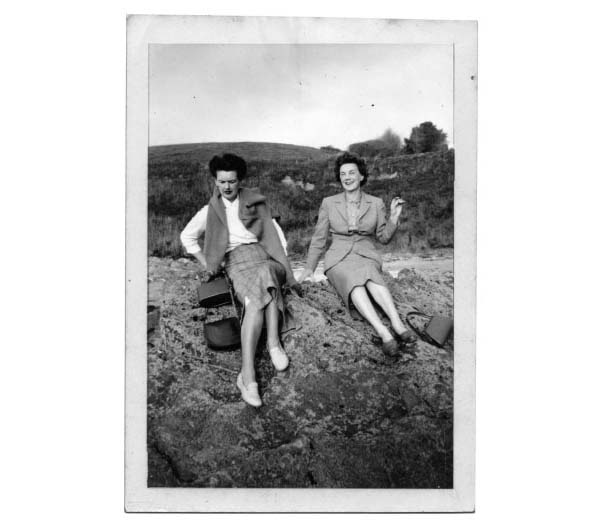

'Mrs Phyllis Murray and yrs truly in Cornwall.'

'Mrs Phyllis Murray and yrs truly in Cornwall.'

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Solvent again! At least for a week. I got home on February 1st and said gaily to Mother, 'Only four weeks until payday, dear!' Mother, somewhat disbelieving, made a remark about it being payday that very day (which it was) so I told her that when I had paid my debts and bought flowers for a friend who was ill, and china ducks for another who is dying (to console her for the loss of her own pet ducks, taken by a fox) and paid the garage and my insurance and so on, out of a salary cheque of £45 I had exactly £3.15s.0d left!!! However, Mac gave me £1 towards the cost of the garage, so I feel reasonably solvent again, and able to face life without worrying whether I shall have to walk home in the absence of the bus fare . . . . . . What a life. However, I still haven't touched my savings, which is the main thing, and next month I shall have so much spare money I hope to put another £10 in the Bank . . .

Yours very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . I was moaning last week about the cold weather. Somebody must have heard me, because by Saturday night the temperature had risen from 20o to 49o F, and Sunday was a really lovely day. We took Mother out for a drive in the afternoon, with Mac doing the driving, and for once I was not nervous in my seat at his side. The reason was that our brakes are binding so badly we are terrified of using the brakes at all, so Mac drives with the aid of the gears and cuts down his speed for corners and so on by taking his foot off the accelerator well in advance, and, then, if that hasn't brought our rate down enough, he will change down a gear. Very comfortable motoring indeed, it makes, and I am all for the brakes to go on binding indefinitely. The cold weather, alas, had another effect on the car – it put paid, finis, phutt, to the battery. My Resolution Not To Draw Money out of The Bank lasted until February 6th, but it was a nice resolution while it did last . . .

Last night, in my opinion, every single member of the Civil Defence who turned up for their lecture deserved the gold badge which the Government is giving those of us who complete 100% of the training programme. 80% entitles you to a silver badge, which is the highest most of us can hope for. But last night should have counted for the whole thing, for it was bitterly cold, with a violent, knife-like wind and, when we eventually reached the lecture room (ten minutes walk from any bus stop) we found we were having instruction in map-reading and had to sit at map-equipped tables spread around the room, and not, as we had hoped, in a tight little bunch around the only radiator in the place. However, the map-reading was interesting and maybe I learned some-thing of use, although most of the 'tips' we were given seemed to me gravely suspicious. For instance, we were being told how to find North: Compass, which we were unlikely to have. Churches, built East and West. OK. If we could find a church. Trees likely to grow close together on the S. or W. of hills. Fiddlesticks. Moss growing on the West (instructor) or South (instructor, five minutes later) or North (my own belief of many years). Not helpful. I said, 'Isn't there a way of telling North by using a watch-face?' Yes, there was, said the instructor, but he'd only discussed it at the Government School for Instructors, with the other pupils there, and they hadn't been able to work it, because they understood you pointed the hour hand at the sun and the North was where the minute hand was. Nonsense and fiddle-de-dee, said the class. North is halfway between the two hands when the hour hand is pointing to the sun. Well, I've just tried it and in fifteen minutes North has moved from one side of my office to the other. There is a way of doing it with a watch, but I still don't believe I know it. Do you? Of course when the sun is out it does give you a rough idea of the general direction of North and South, providing you know the approximate time of day – whether it is morning or late afternoon, for instance, and presumably most of us know that. We were also told to use telegraph poles, which always bear the cross-pieces on the side facing towards London. But what if the road isn't going towards London, but at right-angles to such a road? They certainly don't add the cross-pieces sideways just to help lost souls find their way to the North Pole. As for finding it by the North Star, that, to me, is like Mrs Beeton's recipe for Jugged Hare – 'First, catch your Hare.' However, I learned enough of map-reading to be able to complain bitterly that two of the map references given us on the blackboard in a test we took at the end, weren't on our maps at all. Neither were they. We were given seven references, which indicated places in which the road was blocked by bomb debris. Then we had to plot our route, using only first- or second-class roads, from Bournemouth Square to a rendezvous by Blandford Railway Station and give the mileage involved. All I have to do now is to remember what I learned . . . . . .

. . . I was reading this week in the paper that two gentlemen in America were suing a railroad company for half a million dollars because a train they were travelling on arrived at the race-track too late for them to place their bets on a horse which, in the event, won and would have won them $200 had their money been on. I have an idea that in England you can't sue anybody for more than you have lost by their negligence; perhaps these two American punters are the original discoverers of a new gold-mine. You might let me know if they succeed, and next time the car is (as now) out of action and the bus is late I shall sue the Corporation for, oh, say £30,000 – a nice round sum – for loss of prestige and morale.

You may keep your term 'gas' for the stuff cars run on. I prefer our 'petrol'. After all, gas is a term embracing many forms of gas, from the very air we breathe to deadly poisons and anaesthetics. To call it gas is too general. To call it petrol does at least distinguish which gas it is. I must say I am trying to be impartial, for there are many of your terms which I think preferable to ours; but gas isn't one of them. Nor is elevator. On suspenders v. braces I am biased slightly in your favour. On drapes v. curtains I prefer curtains, because they aren't invariably draped. Slip v. petticoat leaves me undecided. I prefer petticoat from the sound, although it isn't a coat, petit or otherwise. And it shouldn't be a slip, though it sometimes does. I definitely prefer car to automobile, which is a nasty made-up sort of word; but on the other hand I am all in favour of movie instead of pictures. Incidentally, I saw Gene Kelly in It's Always Fair Weather this week, and, as with all his films, thought it utterly delightful; witty, kindly, colourful, beautifully danced, and in extremely good taste . . .

What a long letter – and the second this week, too! Must be the cold weather keeping me energetic. Goodbye for now while I go and feed my sparrows dotted on the windowsill, thinking, poor things, that the flakes of snow are breadcrumbs.

Yours most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Do you realise – bet you didn't – that March 22nd sees the seventh anniversary of my first letter to you? There is a note in my 1949 diary against that date, 'wrote Roady's Father.' At that time, you see, you weren't an individual in your own right – you existed only in relationship to your daughter; but you have grown quite a bit since then.

Certainly I must say you have grown quite a bit more sensible. Your reply to my original letter started, without salutation or preamble, and date-less, address-less:

It was interesting to learn that you enjoyed eating a squirrel cooked in a bag in Central Park and also watching some old hen making off with another paper bag to stuff in an egg in her nest, at or near New Orleans. Nature is wonderful!

No wonder I wondered what made the American people so! Especially as you went on to say all Englishmen in novels were so intensely repulsive, and finished your letter by putting my name (wrongly spelled) and 'R— Drive, England, so help me'. I cannot tell you whether your opinion of England and the English has undergone a change since that date, or whether I have merely worn down your rude comments by throwing other rude ones back in exchange. However, you seem to be able to understand my letters, and do not get quite so mixed up as you appeared to have done over my account of the Central Park squirrel dragging a paper bag up a tree and into its nest.

Last Sunday, as we were clearing luncheon, I said to Mother, 'Would you like a ride this afternoon, dear, or do you prefer to have a rest?' You will notice that there are two clear questions there. One would imagine that such a question called for a reply choosing one or other of the alternatives. But anyone imagining that would not know my Mum. She answered, 'No thank you dear, I know you want to get out and dig the vegetable bed over.' A veritable mind reader, that dear lady is. In reverse. The last thing in the world I wanted to do was to dig the vegetable bed over. And of course, you can guess what I did. Yes – my back still aches . . .

Until next Saturday, then, thank you for your letters, all of 'em, and keep well and happy.

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

PS Have I said thank you yet for Reader's Digest? I got full marks in both the word exercises. Genius, of course.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . We had a lecture at Civil Defence this week on rescue from crashed aircraft. I thought it a waste of time, as the likelihood of any particular person being on the spot when a 'plane crashes is so remote as to be almost non-existent. However, you never know when odd knowledge might come in handy. Of course, I upset the lecturer no end by my questions – particularly as, having worked on aircraft during the war I knew more about them technically than he did – and he got quite put out. But, after all, when a man tells you the only practical way to break into a crashed civilian aircraft is over the windows, somebody with a mind like mine (like Kipling's Elephant Child, that is) is bound to ask how you are expected to get up as high as the windows. 'Well, you'd just have to use your common sense' he said to that one. And then, when I remarked that it was all very well showing us a poster of a crashed Army 'plane on which the starboard engines were on fire and the escape panels were all on the port side, but how did you get the crew out if the port side engines were on fire because there were no escape panels on the starboard side? He looked with loathing at me (poor man, who can blame him!) and was heard to mutter something about 'common sense' again. I take it he meant your common sense would tell you it was hope-less so you might just as well leave the wreck and go to the movies. Never mind: I now know how to break into a crashed aircraft provided it comes down close enough to the earth for me to get onto the wings, and providing the fire (if any) is on the starboard side of the machine, and providing I get to the scene of the crash in time . . .

Bought my brother a pale green nylon and pure silk shirt for his birth-day, on Monday, at an astronomical figure and an even greater figure on the sale-ticket. I bought it at a reduced price because it was the last of the consignment and they were wanting to sell it before putting the new lot out – at even greater, astronomical prices. I do feel sorry for men: you have such dull gifts on your birthdays and so on. The only time I gave my brother anything exciting, it was an after-shave lotion and brought him out in a rash. True, he did give me something exciting once – a hand shower set for attachment to the bath taps, which he used fourteen times that particular weekend, but as a general rule he gets very dull bits of clothing. And please, I ask you, don't write back and suggest either emer-ald cufflinks or gold wristwatches because he has neither and is most unlikely ever to own them.

On Thursday evening, on my way to Civil Defence class, I dropped in at a friend's flat to deliver our family gifts to her for her own birthday. Now Dorothy lives alone in a flat, and when she is not there she tucks the front door key under a ledge at the bottom of the door. So I felt there, and got it out and opened the door. And there, on the door-mat, was a tiny bottle of milk. On the first stair (Dorothy lives in the upper flat) was a small pile of letters. On the second, a small parcel. One above that, a cardboard box containing (at a guess) groceries. One up another wrapped gift. Above that, the second delivery of mail. I put my lamp-shade on the sixth stair and Mother's on the seventh, with Mac's card on the eighth. This took us nearly halfway up the staircase, and I felt quite sorry for Dorothy when she came home after working for 14 hours, having to collect and carry all this stuff upstairs. It seemed to me, also, that the hiding place for the key wasn't terribly secret . . .

Now I must go and help in the café: I am on my own today, and the place is absolutely swarming with small children. I know washing-up isn't quite the thing for a Baths Matron and Secretary to do, but it is out of sight of the public and I don't see why I shouldn't help a very good staff when they are being run off their feet and I am not. After all, I have never laid any claims to dignity, much though I would like to be able to do so.

So, until next Saturday, au revoir, and I do hope your weather is better and won't be such a foul nuisance again for a very long time.

Yours most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

What a sad indictment on modern manners! A day or two ago I had notification from Barker & Dobson that a parcel of candy (your gift) had been dispatched to me, and adding coyly that they thought the sender would be pleased to be advised that the chocolates had arrived! As though I would need a hint to write and thank you! A tactful reminder not to forgo the pleasure of saying thank you, and of telling you what a very well-chosen parcel it is!! Which reminds me:

First child: We've got a radio set and television and a washing machine and a car. You don't seem to have anything here, do you?

Second child: Oh, we've got manners.

So now Easter is here and we shall be able to guzzle ourselves, and be large-handed to any friends who may visit us: And B & Dobson's hint or no, we all thank you most sincerely, and wish you to have as happy an Easter as you well deserve. I do hope all that snow has gone and you are no longer confined to the house by mountainous drifts; and that both you and the birds got through the bad patch satisfactorily.

Thank you again, very much indeed,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . It is only Thursday today, and I am stuck in my office waiting, as usual, for my brother to arrive and take me home. On Tuesday this week he hadn't arrived 40 minutes after I left the office, so I went home by bus in a terrific temper. And he sulked because I was angry. Said (to Mother. I wouldn't speak to him) that he became very busy a few minutes before he should have left the office, and forgot all about telephoning – or asking one of his staff to do so – me not to wait. He is always fairly sorry to keep me waiting, but always sulks if I am annoyed by it. I nearly gave him my share of the car, then and there! As my boss says, I could come to work and go home by taxi and it would still be cheaper than sharing a car with my brother! Ah well. C'est la guerre or something.

Friday, I shan't have to go to work. I know I should go to church, but as a day off is so rare a thing I am going to motor Mother down to Lyme Regis instead. Her brother living there has been rather ill lately, and I know Mother has been longing to go and see him. So we shall take her, and have a picnic lunch on the way if the weather holds – at present it is fine but not sunny. I have bought a bottle of white wine to go with a tin of chicken Rosalind sent in a parcel at Christmas. (Mother dreamed the other night how nice it would be if we could have a picnic with tinned chicken if we had a tinned chicken and we had a picnic – and in the morning she got a chair and climbed on it and looked on top of her wardrobe – where, surprisingly, she keeps such things – and there, in solitary state, was a large tin. Of chicken! So we are all set.)

And, of course, we have the chocolates and the creamy mints, and so on, from your Easter Egg. And I have bought Mother a pale green cardigan and Mac green nylon socks, so all together our outing should be perfectly Easter-ish.

I am afraid this will have to be a short letter: I can hear Mac honking away out the front – his polite way of informing me he is here, and although he has no real objection to keeping me waiting, of course it is lese-majesty to do the same thing to him. So I must away in a hurry.

Yours very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

This, being the first full week of our summer water show, is always one of the busiest and most headachy in the year for me. This year, opening night came and all my staff arrived – except TWO. These did not have the common decency to telephone and say they'd changed their minds about coming to work for us, and thereby left us in a complete flap five minutes before the audience came in, as we hadn't enough usherettes to show them in, nor doormen enough to take their tickets.

Since then I have written to five more, not one of whom has bothered to answer – even to say 'No', and have arranged for two girls who were friends of those already working for us – and they, bless 'em, did have the manners to telephone and say 1) that the parents wouldn't let them work in such a place as the Baths, and 2) they didn't want to work Saturdays. Ah well . . .

But to more cheerful matters. Let us start with Mother. She went down the garden on Thursday, a very warm and humid day, and got bitten by a midget. According to her. It's another one of the book of Mrs Woodsford Malapropisms, and, I think, a very good one.

It was raining a little on Thursday, so instead of giving my genius to outdoor painting class that evening, I gave my services to the good of my country, and turned up at the Civil Defence class. We were on a small exercise at the 'bombed' house, where I was given a label reading 'Fractured femur' and told to drape myself over some rubble and be a casualty. Fortunately I was also given a blanket as well as a label, as the grass was both long and wet, and the rubble was dirty and uncomfortable, being composed of bits of old iron, bricks, loose odds and ends of wood – in fact, just the sort of thing you would get around a bombed building. I lay there on my little blanket for ten or fifteen minutes, until the rescue party discovered me, and listened to a cuckoo in the next field echoing my thoughts exactly.

. . . I must, of a surety, be my mother's daughter. Last evening, I was working late and, on reaching home, had my supper in bed. I was a bit worried about something that had gone wrong, and was thinking of possible causes when I noticed I had taken the stopper out of the vacuum flask and poured my coffee – over my salad. As I told you of Mother's meeting with the midget in the garden (it drew blood, she said) it is only fair that I should tell you about this episode as well.

And now it is Saturday morning, and there is so much to be done I can't spend any more time writing to you – I got to work at 8.30 so, in any case, only having from 10 p.m. to 8.30 a.m. to go home, feed, and sleep, I am in no real condition to write bright letters anyway. So au revoir until next Saturday.

Yours very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

You are letting your side down, Sir! Do you realise that the Bellport Grapevine (your nom-de-plume) did not let me know that Rosalind was flying to France to take a coach trip next month? I found out from Mrs Beall in London, who said Rosalind was dreading having to write and tell me she was coming to Europe without visiting England. Poor Rosalind! Does she see me as a sort of ogre-spinster, all frowns and recriminations, I wonder. I seem to remember friends being chary of giving me bad news before; it gives me deeply to think. Either they believe me to be so tender-hearted I shall be quite broken up; or they are scared stiff of my reactions. Of course I would naturally prefer the former explanation, but there is sufficient element of doubt about it, for, as I said, serious heart-searching on my part. I wrote to Rosalind within a couple of hours of hearing, giving her my complete permission to visit Europe any time she chose, and graciously forgiving her for this lapse on her part. My only reaction is a somewhat plaintive wish that I could take the tour as well; but as that is impossible from all angles, I just hope the four ladies will have a wonderful holiday. Coming from an ogre, that's pretty generous wishing, don't you agree?

I listened to Mr Truman last night on the radio, speaking at the Pilgrim Dinner given in his honour. He was an easy speaker. He told a tale of Lord Halifax – a previous speaker – who was showing a party of American ladies over the British Embassy in Washington during his Ambassadorship there. On the walls of the staircase are hung, as no doubt you know, portraits of the English monarchs. One of the ladies stopped before one, and exclaimed, 'Oh, what a handsome man – and what a kind face! Who was he?' Lord Halifax paused before the portrait of George III to collect his thoughts, and then said, 'He was one of the founders of your Country, Madam.'

. . . Now for London. I came back late Sunday night. Later than I had expected, but that's railways for you these days – they run to please themselves. In fact, the 7.30 p.m., which I was catching, wasn't even shown on the Departure Board. The first thing, the thing of paramount importance in England – the weather, was foul. However, we 'did' Westminster Abbey, which I hadn't seen before. I did go inside one day, many years ago, but whether I picked the wrong door, or what I did, I don't remember but it looked so like an old junk shop I came straight out. This time I was stronger of will, and went around like a good little tourist . . .

We went also to the Tate Gallery where I wanted Mrs Beall and Miss Henry to see the luminous Turners, and the French Impressionists. Alas, it turned out that they much preferred Watts's Hope sitting on top of the World, which they had seen on umpteen Christmas cards and calendars! Then Mrs Beall and I went to Windsor to go over the Castle, only to find a) it was Sunday and the State Apartments aren't open, and b) St George's Chapel was also closed as there was a service going on, and it was to be shut, anyway, until Tuesday, when the ceremony of installing a new Knight of the Order of the Garter took place. So we were blown from the ramparts by the wind (I noticed in the paper, the Queen was dealt with in the same way at the Tuesday ceremony, nearly being blown overboard in her heavy cloak, and almost losing her plumed hat, to the great amusement of her two children, watching nearby) and had lunch in a very old hotel in the town . . .

And then, of course, we went three times to the theatre. We saw The Boyfriend which is a delicate take-off of the 1920s and quite enchanting. Mrs Beall wasn't impressed. She is a very unimaginative person, and kept saying, 'I'm sure we weren't as silly in the 1920s, quite sure.' I don't suppose they were – the whole thing was a delicate exaggeration of the manner in which musical comedies were presented on the stage then. The girls wore knickers with elastic just above the knees; their swimming suits had legs almost to the knees, and brightly coloured bands around the hips. They wore bandeaux around their eyebrows, and they were so sweet and so utterly refined it was difficult for them to get the words out of their plum-like mouths. We also saw Edith Evans and Peggy Ashcroft in The Chalk Garden, which was exquisitely acted and we all loved it. . . Finally – only we saw it first, which was a mistake: it should have been the final item on our programme – we saw Alec Guinness in Hotel Paradiso. This is a French farce, some 80 years ago and still, like some people, going very strong indeed. It was a joy, a wonder, a jaw-acher, from beginning to end – and the timing, Mr Bigelow, must have been done with a stop-watch timing the stop-watch. The scene was a gloriously run-down hotel interior, absolutely perfect of its kind. And every time I think of it, I laugh – especially the bit where Alec Guinness (M. Boniface) has explained his presence in the hotel to a neighbour, who is staying overnight, by saying his wife always said to him 'Any time you are passing the Hotel Paradiso, do run in and give my regards to Madame Cot' (she was the friend's wife, with whom Boniface was hoping to spend the night). Next time he was confronted by his awkward neighbour, Alec Guinness was hugging an old-fashioned stone hot-water bottle (he was feeling ill from the effects of too much wine) and the best he could do on the spur of the moment was to say his wife told him they did a very good line in hot-water bottles at the Hotel Paradiso, and any time he happened to be passing, to be sure and pop in and get her one. Probably that doesn't sound very funny; it needs the genius of Alec Guinness to brighten it, and I can still see him and you probably never have.

Now it's half past five and I must get going with the evening work. It's quite nice to be peacefully back at work: I must say trying to keep two very different characters (and different from one's own) happy over four days in bad weather, is quite a strain. And so, au revoir until next Saturday.

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . We went to Horsham last weekend and passed a side-lane with the post saying STEEP, and, under that, SLEET. I asked Mother whether she would prefer to live in Steep or Sleet, and (being Mother and therefore practical before all else) she said it would depend on what they looked like. I gave up. Next we came to a turning leading to WOOLBEDING. Take the slightest pinch of poetic licence over that, and what a delightful place to have for your home address. And then on Sunday, when the Observer came, there was an article all ready for me to cut out and send to you, based, as this letter had intended to be, on place-names. Every single one of these names is the name of town or village: the author has merely put them in a list, removed their capital letters, and played with the idea that there are so many words in a dictionary. We loved his idea of the meaning of Bovey Tracey (Bovey is pronounced Buvvy) – but most of them are good and some are excellent, so I will leave you to enjoy them for yourself. What can you do with Long Island name-places? Or place-names? Quiogue – a form of rheumatism accompanied by shaking; the palsy. Mastic Beach – putty used in sticking wooden houses together. Rampasture – an aggressive attitude, a posture. Speonk – a rude noise. I am sure you can find many if you delve into the old original names, and avoid the made-up ones like Holtsville and Port Jefferson. I see Hauppauge, and Nesconset, Ronkonkoma and Sweyze (Hay Fever) and there is Aquebogue (the normal number of strokes taken at the water hole on the golf links?) and Peconic Bay. You could get up a sort of parlour game with this for the long winter evenings . . .

Yours most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Before I go any farther, let me breathe a deep sigh of relief that the last show of the 1956 Aquashow has been on the calendar. If this place were a proper theatre, there would be arrangements made for adequate working conditions and hours; but as it is, a swimming pool by day and a theatre by night and the staff working the lot, I find 19 weeks non-stop is too long. In a few weeks, when the galas are over as well, I shall be able to relax and perhaps dye a few million white hairs and regain my lost youth, ha ha.

This has been a week, to be sure. The town has been full of Baths Superintendents, Managers, Deputies, and their Chairmen and Vice-Chairmen. My boss has been flitting from office to Conference Hall and back again; and then, quite suddenly, and without any warning what-soever, the whole lot descended upon us on Thursday afternoon, in the middle of a downpour of rain and a right hearty gale. They had decided, apparently, to come and spend the afternoon going around the Baths.

By half-past the last visitor had gone, and by 5.45 p.m. we had washed up everything we could find, cleaned ourselves, counted programmes and money, and organised everything ready for the evening performances of the water show. We were, I may add, noticeably shorter, being worn down to the knees . . .

One of my less brilliant cashiers came to my office while I was at lunch the other day and said, 'Oh, Miss Woodsford, where are they to put the goat?' I said 'Goat, Mrs Allen? What goat?' 'Oh – the goat the Pavilion have sent over for the Baths to stable for them.' I swallowed hard, and then after counting ten remarked fairly mildly that if the goat was too much for the Pavilion to stable I hardly thought the Baths Department was likely to accommodate it for them, and why didn't she tell the goat (and attendant) to try the little hut on the other side of the road where, in previous years, they stabled the donkeys the children rode on the beach. My cashier thought this was a wonderful idea, and was overcome at my brilliance in thinking of it. Adding to my own great knowledge her own wish to be helpful, she told the goat (and goatherd) to go to the shipping office and ask there, where no doubt they would tell them where to go. I am quite sure the shipping office manager, confronted by a goat, would do so. The goat is appearing in Teahouse of the August Moon at the Pavilion, and it is not (I repeat, NOT) being stabled in the Baths, which remain reasonably hygienic.

We have been dashing around at weekends with my brother, retrieving runaway or just lost little boys on his list of children. Sunday before last it was Adrian; last Sunday, Malcolm. Adrian is a maladjusted child, age about ten or eleven, and he goes to a school for such children miles and miles into the heart of Dorset. He was in the Children's Home in Bournemouth for the school holidays. On Sunday, then, he got up about six o'clock, packed his pathetic belongings in his one suitcase, and set off, stealing a bicycle as he went and pushing the suitcase along, balanced on the saddle. This he found a bit tiring, so he hid the case under a bush and went on, pushing his bicycle, until apparently he noticed another bike he liked better, when he did a swap. When he was eventually found, he was pushing yet another bicycle – it was about the sixth he'd had – and following along behind the Salvation Army Band.

We had to hurry with this one because he had, about three hours previously, been given travel pills which were expected to wear off any moment now. So we kept a wary eye on his colour and general disposition on behalf of the upholstery. When we arrived at the school, it was a really ancient place – it was in Domesday, we were told – practically falling to pieces, and smelling of moth balls, must and mildew in equal parts. After sitting in the car for an hour or so, waiting, Mother and I were invited in for a cup of tea or, at least, a warm by the fire. The little boy played host and did it very well indeed, all his apparent shyness and awkwardness in the car disappearing as he discovered he was not, it seemed, in dire disgrace for his behaviour. He had 'laid the table' – he had brought in a large tray with a big brown teapot on it, four glasses (yes) four white plates, two or three enormous knives, a plate with some pieces of bread, pieces of cake, and lumps of 'I-hope-it-is-butter' on the edge.

The lay sister who was then in charge – the school is normally run by an Anglican Order of St Francis, the monks wearing the usual long brown habit and sandals on their feet – told us a bit about these maladjusted children, the trouble being, in her view, that none of them get enough loving when they are very small. She believed that babies need to be loved for a very long time before they are capable of loving on their own – they can react to affection and love quite early on, but remove that affection and they are lost, as it takes years and years for the habit of out-giving to be formed in them. And these poor little boys all lack that individual love of parents in their lives. She said they had a farm attached to the school, and when they reached the age of 14 all the boys gave good help on the farm. 'You see,' she said, 'it's so much easier to have a relationship with an animal than it is with a human being, so they tend to take the easy way out of their difficulties in getting adjusted to living with other people.'

One thing I disagreed with her over: I did think the child was losing something if he was not told off or punished, or at least lectured, on the naughtiness of stealing bicycles and wandering off without telling people, and giving so much trouble to everybody. If the children are not treated as normal children, how can they get a normal outlook on what is right and what is wrong? . . .

Now to get this off to the post, if I can reach the pillar-box through the gale now blowing. One walks in a horizontal position in order to keep even remotely upright, the wind is so howling-strong.

Yours very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Yes, thank you, I not only did read the Dorothy Parker poem about various reasons for not committing suicide – I still have it, in the book of her work you sent me for Christmas some years ago. It seems a very poor collection of reasons, in a negative way, but I daresay if it works, it's sufficient. I did myself have a distant cousin who walked into a river with the intent of killing herself, and when the water reached her armpits she was suddenly struck by the awful thought that she'd probably catch pneumonia, doing things like that. So she walked out again . . .

On Sunday last it was a lovely day, clear, sunny, and with small white puffs of cumulous clouds dotted high in the sky. I suggested a picnic, which the family thought an excellent notion, so we had lunch early and set off about two o'clock. Our objective, Bulbarrow. Barrow is the name for an Ancient Burial Ground, and I don't know where the Bull comes in because, as you know, that is something I never indulge in. Anyway, Bulbarrow is a sort of horseshoe shaped hill, and on the outer side – as it were – you look down a long narrow valley, with forests on each slope, to one of the Stately Homes of England (ex, now a boys' school). A dozen paces or so brings you across the spur to the inner side of the horseshoe, and there you look outwards over the Blackmore Vale, a wide and fertile valley in Dorset and Somerset which is a famous dairy area . . .

Well, we reached Bulbarrow and found the best spot for parking the car, where you get both views at once (if equipped with eyes both sides of your head, of course) was occupied by about a dozen cars. We were cross, but not too put out, and turned along one arm of the crescent, to park by the side of the road. Unfortunately, as we progressed, we found the place was stiff with cars and motorcycles, perambulators, caravans, religious placards, and thousands and thousands of people, drat 'em. We had arrived right bang in the middle of the last big motorcycle 'scramble' races which take place up and down the side of the hill. When we eventually found room enough to put the car off the road, and had our picnic on the high bank on the opposite side, we were some two miles from the very top of the hill, but still within easy listening of the loudspeakers and eternal buzz-buzz of the cycle engines, as they fell down the hill or pushed themselves up. We had sandwiches and tea, very crumbly cream cake (Mother said it was a nice cake for an alfresco meal, because you could just drop the crumbs anywhere and it didn't matter) and more tea to the accompaniment of appeals for doctors, people who'd lost children, and children who'd lost their parents.

. . . Yes, you may well have read about some Russian woman lifting some small hats in a London shop. It is still simmering; a regular storm in a samovar. Apparently this woman – she was one of the Russian athletes visiting England officially a few weeks ago – went shopping in a big, cheap London store and collected half a dozen out-of-date, and cheap hats. Nobody knows whether she just didn't know how you went about paying for hats in England. Nobody, apparently, knew what language she was speaking for a long time, which cannot have helped anybody. The store has a strict rule about charging pilferers, and they took the same line with her. Once they had discovered who she was, I think they might have given her the benefit of the doubt, but they didn't, and that was that. The charge was made; the Russians exploded. The rest of the team went off home in a huff, and everybody said rude things about the British Government for not stepping in and quashing the whole thing. Now the whole point of the Brit. Gov.'s answer is this: in England, the Government has no say whatsoever about the judiciary. By this time the big store had got a bit scared of all the hullabaloo, and it was suggested (by whom I do not know) that the Public Prosecutor should take the case over, which has been done.

And now, the silly woman – who, we all realise, has only to appear in Court and, through an interpreter, tell the Court what she was up to, to have them say 'Well, we're sorry there has been a misunderstanding, and goodbye' – she is still being held incommunicado in the Russian Embassy; she won't come out for fear of being arrested, and until she does come out, she can't get home to Russia . . . It's all too silly for words and the amount of hot air that has been circulated should keep us warm for the rest of the winter.

Last week I entered in the Football Pools competitions, and one of my three lines got 20 points, only one point less than was necessary to win a prize. I told Mac this, and he was extremely interested and suggested I should use some system or other, by which you calculate the mathematical chances of the teams drawing their matches. I said coolly, 'How else do you think I did them?' Mac was terribly impressed, so you won't tell him, will you, that my mathematical calculations netted 14 and 17 points respectively, and the 20-point solution was based on my initials, plus my age, plus my lucky number? This week I am almost certain to win astronomical sums, as I have done the solutions with a pin. If I win, oh say £70,000 I might even send you a cable to tell you. If not, you'll just have to wait until next Saturday to hear my excuse . . .

Only two weeks to go, now, before my holiday . . .

Yours very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

It is a fine, chilly, sunny week, this week, and people are still swimming hardily in the sea. Others are sitting about on deckchairs on the beach and Promenade, and every wooden bench in the Gardens is filled with people. My boss is on holiday, no doubt revelling in the fine weather and putting off his return as long as possible. As it remains fine the longer, so the odds lengthen against its continuing that way for my holiday, so my heart is going down and down into my boots. But it may be kind yet; we shall see.

The joke of this week is the appearance of Miss Marilyn Monroe with her husband Henry Miller at the first night of his play View from The Bridge in London. Miss Monroe gave it out that she intended wearing something simple, in order not to steal the limelight from her new husband . . . So last evening she dressed in something simple for this opening performance, and today the newspapers are full of photographs of Miss Monroe's dress, which in turn is full to over-flowing of Miss Monroe . . .

I have read Under Milk Wood, and one or two other books by Dylan Thomas, and I must say I agree with the critics that he is a wonder of the century. Do you think, when he began to get well known and, in a tiny way, lionised, he found his emotions got a bit dragged out – or worn out, perhaps – and getting a good strong drink in him made him feel more sensitively – or made him think he was feeling more sensitively. And that was the beginning. Next day there was the horrid hangover, and a drink put that right. And more people trying to dig a little memento out of his personality, so that he had to drink a bit more in order to avoid feeing he was being torn, little by little, to bits. It seems an expensive, and terribly unpleasant way to commit suicide. Towards the end of his life, Dylan Thomas used to complain of the awful feeling of dread he had always, and of a tight band of iron around his head. I often get that, too . . . . . . do you think I'm going to break out into matchless poetry any moment now? I am sure it doesn't come of drink, in my case, unless you count six bottles (each containing three wine-glassfuls) of ghastly wine Mr Markson gave me a month ago, and which Mac and I have shared with the sink . . .

All for now, I hope you are well, too,

Yours very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Your letter of December 13th was waiting for me at home yesterday when I reached there, together with a small pile of Christmas cards. On my brother's dinner-mat was one single, solitary envelope! He was so mad!! Gets furious because I have so many more cards and gifts at Christmas, and gets even more furious when we try to get him to acknowledge those he does get. He seems to imagine friendships, at a distance anyway, grow naturally, like little apples, without any help on his part. Perhaps his memory is to be so strongly in his friends' minds that no letter-writing is needed to remind them he is still about the world . . .

No, no! You mustn't look or feel like Sir Anthony Eden, with your new walking stick. You look and feel like Sir Winston Churchill, instead. Much more satisfactory. I believe the right thing to do with a stick these days (for of course fashions change) is to put one hand over the other on the handle, and holding the stick centrally in front of one, to lean some-what on it and look down over it at whatever small boy one wishes to impress, with lowering look and beetling brows . . .

As a sort of holiday-task I have started on another of those patchwork pictures, of which you have a sample at Casa Bigelow. This one is for Rosalind (if I get it finished). Not realising how ambitious I was, I drew a sketch of the street at Clovelly, the little Devonshire village we all stayed in one night in 1955. Then there is Rosalind, Mrs Olsen, and me (pushing Mrs O.) climbing up the street in the morning, watched by an amused donkey looking over a wall. Well, that sounds alright, but there are thousands of tiny bits of material to be cut out and fitted together, and until I started, I never realised quite how many! Would you tell me, when you write, if you are expecting Rosalind to come and visit you say around her birthday date. If she is, when it is finished I will send the picture to you and ask you to give it to her when she comes. That way you'll both get to see it. Otherwise, if I send it straight to Alton you might never have the opportunity to say how clever I am, and I should hate that. Don't forget, then, to let me know when you next expect her . . .

Tonight when I get home there will be the lovely vision of nothing to do. No chores, that is. All my parcels are packed and ready for delivery by hand, or have been posted. All my household jobs have been finished (for the decorating of the living room I shall leave until January) and my hair is washed, as well. So I can sit by the fire and get on with my embroidery, which, now that I am started, is fascinating me. I sewed it so often to my skirt last night I finished by kneeling on the floor, with the embroidery spread out on the carpet, tacking the tiny bits of mosaic materials on. I have even gone so far as to have two shades of grey for the cobblestones; one in the sunshine, and the darker shade in the shadow from the houses!

. . . Even if you don't go to your son's home for Christmas, I hope you have a very comfortable, warm, cosy one in Bellport, with half the town popping in from time to time to wish you joy and smother you with mufflers, cigars, bottles of hooch (or whatever you drink: might even be methelated spirits, for all I know) and their neighbourly affection. Anyway, have a wonderful Christmas, and a very happy, healthy, New Year full of interesting happenings and good books and pleasant sights and deep sleep.

And thank you for all your entertaining letters this year; and your many kindnesses.

Yours most gratefully,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Christmas is over, and we are (more or less) back to normal, although I am still having belated cards arrive, and those we have had and pinned up are still giving us heart attacks. You see, one year we hung them over strings, and they looked like so much wet washing hanging about we loathed it. And for years we pinned them to an old screen only that has now collapsed with old age so another place had to be found for them this year, and some bright person told me to stick the first card with Scotch tape to the picture-rail, and then stick each succeeding card to the one above it, until you were able to fasten the lowest one to the skirting board. This we have done, and they look very gay, if a bit untidy, all along one wall. About once every seven and a half minutes the weight of one or another is too much for the top bit of Scotch tape, and the whole thing slips off the varnished wood and collapses with extraordinary loud noises, considering that it is only a dozen or so cards falling down. Usually, at least one card depicts the flight into Egypt, and features a donkey. But this year, because I am frantic for details about donkeys for my Clovelly 'picture', there is not one in sight!

. . . Everybody in America this year sent me something edible! On Christmas morning the last parcel arrived, and Mother, who was looking at the label, said, 'It's for you, dear, from a Jane Henry, and it says "Cake Mixes" but I expect it's more than that.' But it wasn't – it was two packets of cake mixtures, to our huge amusement and delight. Amusement because I just couldn't imagine sending such a thing to any-body, and delight because one of the mixtures was of an Angel cake with the equivalent of 13 egg whites in it, and although I have for long wished to make an Angel cake I've never a) had 13 eggs to spare, or b) known what to do with 13 yolks if I had a). So now I shall know what an Angel cake tastes like, when we finish our Christmas cake, and our ordinary cake, and the rich fruit cake that was part of Rosalind's parcels. About the middle of February I will report more fully.

And now we come to the New Year once again. I know this year I am making only one resolution, NEVER AGAIN TO EMBROIDER A DONKEY! But always at this time I say thank you to you, I know, for all your kindnesses and all your letters, and for all the fun it is, knowing you. You put a postscript to your latest letter, saying something about it being a mistake to grow old; but so long as your spirit is young, what on earth does it matter? And, believe me, reading your first letter (which was more than a little eccentric, as I remember, and puzzled me a lot) and reading your latest one, one would be justified in reversing the two dates, and putting April 8th 1949, on the one I am answering today. After all, if you do have a bit of difficulty getting out of a bath – it is something I understand is regularly experienced by all young mothers-to-be, and by people like me, with the rheumatics. And it gives your agile brain something concrete to work on, to overcome the inertia in your muscles. And if you feel too tired to go out yachting, or pushing the town around, or shooting poor inoffensive ducks – you have all that much more time to spend reading about the world, or writing to me. And believe me, I regard writing to me as far more important than all the yachting in Cowes, Newport or Bellport Bay, and all the ducks in Bombay.

So please don't worry about age: I am going greyer every day, and every day I care less to see more white hairs. And the wrinkles in my face – they are of character, and who would wish to spend a lifetime looking exactly the same? No: if your mind is bright, agile, alert, interested, nothing else matters really. So thank you very much indeed for remaining as young as in 1949 – for the outcome of your mind is all that I see of you, you know – and I hope you will, one day, let me into the secret of your mind's eternal youth, for it is a recipe I should just love to add to my collection.

So on to 1957, and the hell with the calendar, say both of us.

Yours most affectionately,

Frances W.