1957

February 6th (p. 241), 'When you had written me about all the various sick females of your acquaintance, and gone on to say you didn't feel so good yourself, I thought you were cadging for sympathy.'

February 6th (p. 241), 'When you had written me about all the various sick females of your acquaintance, and gone on to say you didn't feel so good yourself, I thought you were cadging for sympathy.'

Dear Mr Bigelow,

The other morning, as I was inching my way between the kitchen table and the dresser, opening the door to the backstairs with my foot, holding in one hand a coal hod and a large spoon, in the other a jug of water, and a colander full of bread for the birds topped by a piece of news-paper holding the seed and crumbled-up cheese – oh yes, and with a tin of rat-poison clutched under one arm – as I was, I said, inching my way along, I remarked to Mother, 'I don't see why I shouldn't brush the back steps as I go down in the mornings, Mother.' Mother turned and looked at me and said, in absolute gravity, 'Oh don't you bother about that, dear – I'll do that, later.'

. . . Everybody feels sorry for Sir Anthony Eden, even me. I dislike him as a man quite considerably, and although I think he did the right thing in Egypt, I think he was weak once he had been strong, and instead of going right along the canal between the Egyptians and the Israelites and saying, 'Now we're here, and we are staying here until U.N.O. does something positive to stop this scrapping', he just stopped when asked to do so, and then retreated when asked to do that, too. Leaving, as Mr Eisenhower and Mr Dulles remark, 'a vacuum'. We got out of the Persian oil fields because America insisted, for the sake of peace – and then, after a time, the vacuum there became too rusty and too dangerous. So what happened? The American oil companies went in and filled the vacuum. Now they are going (not the oil companies particularly, but the U.S.A.) to fill the vacuum created because, by their indignation, Eden gave orders for us to get out of the Middle East. Which vacuum, created by the U.S.A. indirectly, do they intend to fill next? We do so wish to know. But this is merely being catty, and getting away from my subject, which was the retirement of Sir A. I feel sorry for him for, having waited and worked so very long for the position of Prime Minister, he has now to retire in the middle of such a sorry mess, and it is obvious that the U.S. Government – not the U.S. people – will not have anything to do with Eden, and it would therefore merely be a waste of his health, and possibly our future, if he stayed any longer in his job to try and straighten things out. It is an exceedingly sad ending to a long and selfless career, and in spite of my personal dislike, I feel he deserves better luck. And, of course, his going will leave quite a little vacuum again! Heaven help us if we have a General Election and Labour gets back, for you – and I do mean you, the U.S.A. will get Bevan as British P.M. then, and then we'd be in a mess, both of us. Aren't politics the absolute nadir!

Mac and I have got in an awful mess over changing our car. We went around the town, and as I believe I told you last week, narrowed the field down to two Austin A30s. One was 1955, £445 and £85 allowed for ours, and the other was 1956, £515 and £100 for ours. Well, eventually one day this week we decided on the newest car, for although it strained all our resources to the last penny, the car had done only 2,700 miles and we felt that by the time we had finished paying off our indebtedness, the car would be worth more. So Mac and I went up and signed the agreement to buy the car for £515, and paid a deposit. Then Mac signed an agreement to sell the garage our car for £100. And we went home, where Mac consulted our car's registration book – and to our horror discovered it was a year older than we had thought! I had visions of being held to the contract to buy the £515 car, with the other one just cancelled. And as buying it with £100 allowed for our car meant we had to borrow £300 from friends, we just could not possibly raise another pound. Fortunately, the garage salesman told us they would not hold us to the contract if they could not, eventually, 'do a deal' with us. After several days of waiting with churning insides and bated breaths, the garage managed to find a buyer for our car, and the deal is 'on' again. All that now remains is for Mac and me to find the cash! We are, as I said, borrowing right left and centre but hope to have paid everybody back by two years and four months, providing nobody wants anything in the way of extras, holidays, birthdays, medicine, teeth out, or suchlike extravagances for that period. My brother says he is going to stop smoking. If, and it is in capital letters, IF he does, this will save him £6 a month right off, and as I am once more to pay all the car insurance, tax and garage (Mac's share of which is normally £2 a month) that gives him £8 a month to use to pay off our indebtedness. He is aiming at paying £10, so he should not find it too hard a task. IF he stops smoking. But, of course, Muggins here is so horrified at the extent of our loans that she at once said she would pay £4 a month towards reducing them, plus the insurance, garage and so on; and as I have no smoking or other extravagances that I know of, to cut out, I am going to be £6 a month worse off from the word go. At least, for six months: after that I shall pay £4 a month altogether. It should not really be quite as awful as it feels right now, for there should be no repair bills for me to find. Mother is lucky to have the carpet and the oil radiator and new net curtains for her bedroom! The rest will just have to wait.

Now I must get back to work: it is a very cold day, but there is a lovely strong sun out and the sea is almost Mediterranean in its blueness. I hope it is as fine over on Long Island, and that the sunshine is streaming in your living-room windows and fading the colours in your hooked rugs, perhaps! No, I don't wish that: I hope it is merely brightening up any dull corners there may be.

So au revoir until next week, when I hope to write you as the part owner of the Beetle.

Yours, insolvently sincere,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

When Rosalind's letter came this morning I was mildly surprised to read her first sentence, 'Well, here I am, as you will see, at Bellport'. But not more than mildly surprised, as I thought she had 'got to go' to New York when Mr Akin was there on steel matters, and had popped down to spend a few hours with you.

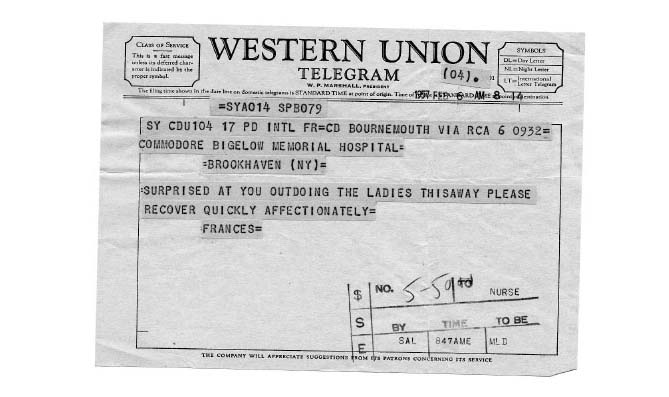

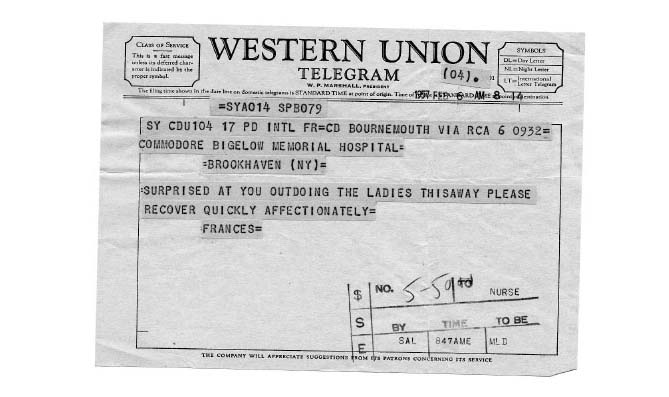

But the second sentence . . . . . . 'if you miss a letter from father for a week or two the reason is that he is in Brookhaven Memorial Hospital having had his appendix removed last Tues. night!' . . . . . . that shook me like the San Francisco earthquake. When you had written me about all the various sick females of your acquaintance, and gone on to say you didn't feel so good yourself, I thought you were just cadging for sympathy. Not that you had any deep-laid plot for doing even better than the ladies. And to leave matters so late before you called your doctor! I am not only surprised at you; I am ashamed of you, Sir.

Especially after all the good examples I have set you – moaning to high Heaven whenever I get lumbago or a cold or a thorn in my finger. What did you think it was, when you started having a pain in your tummy? Had you allowed The Can-Opener, perhaps, to dispense with that instrument, and eaten your meals still in their container, which had disagreed with your digestion? Or have you decided on taking up another career, say as a sword swallower, starting with tin-tacks and practising your way to better things. Or did you just decide, as many people do when they retire from business, to dispense with all unnecessary accoutrements, the appendix being one of them?

Rosalind tells me you had a local anaesthetic and that it hurt horribly. I wasn't sure whether she meant the anaesthetic, or the subsequent operation. I do remember Mac had his appendix out under a spinal anaesthetic, and said it was very nasty; and that he was furious because he had been told it was done to avoid post-operative sickness – and he was sick anyway!

Rosalind tells me you are up each day for a little while, following the newest form of therapy. I don't know how long they will keep you in hospital, and knowing your feeling for hospitals, and knowing, from Rosalind, that you are up and about, I cannot imagine you staying there very long unless they padlock you to the foot of your bed – and even then I am sure you would go into cahoots with the gentleman in the next bed and get a file smuggled in, or something. So I am sending this letter post-haste to the hospital, but I will send the next one to the usual address in the fond certainty that you will be there. I have just thought: was all this to-do a put-up job to avoid having to unpack all that ghastly sticky paper off my Clovelly picture? I am suspicious. Also, glad you are doing so well – keep it up, please, and oblige.

Frances W.

PS Your cane should be most useful for a time, now.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Well, I do hope you and Rosalind had a happy St Valentine's Day, at home in Bellport, and that the sun shone on you both and made you feel comfortable and at ease and invigorated.

I was listening to a broadcast from America one evening this week, and the speaker mentioned the tug-strike, which might have a very harsh effect on Manhattan's heating arrangements, as all your fuel for central heating had to come across one or other of the rivers, and once the tugs were not working, the position might become uncomfortable . . . You see, once I have convinced myself that you are safely home, and well on the road to recovery, then I can find something else to worry about. I must like lines on my face, that is the only possible explanation.

Well, Mac has passed all his examinations. He had an unofficial letter early this week, from the Tutor and Adviser in Social Studies at London University, who has been watching over him these last two years, to say she hoped he wasn't having any sleepless nights worrying about the result, because he didn't need to. The results aren't officially announced until early in March, but believe me, the letter we waved from member to member in our household, to the accompaniment of sighs of relief, cries of 'yippee', and deep felt 'Goods!' I don't think Mac could have borne it, had he failed – as you may remember he was horribly afraid he had done. Now he says he hopes to goodness he's taken the very last examination in his life.

. . . This morning I bumped into Mac unexpectedly in the hall. It was something of a surprise. He had just risen from his bed and was wearing dull blue pyjama trousers and a long, knitted, navy and white striped sort of sweat shirt with short sleeves. It was a garment he removed from somewhere or other before leaving Germany on being released from the prisoner-of-war camp. According to Mac, it was part of the uniform of a Dutch sailor. Wherever it came from, and however he got it, it has shown determination to outlive the entire Woodsford family. At first, it was worn on holiday. Then, in the garden for bonfire operations (practically the only thing Mac does) and now it is sleeping apparel. He looked like something out of the chorus of, say, Fanny, and in case you don't know, that is a musical play about sailors in Marseilles, fishermen, spivs, and so on. I'm not sure which category Mac would come in; perhaps a hybrid fish-sailor, say.

And so, leaving you in my mind elegantly dressed by your elegantly furnished fireplace, in your elegantly equipped room, with, I trust, your health restored to its normal, elegant ruddiness, I will depart until next Saturday. I do hope, said she coming back with an afterthought, you were so well on February 14th you gave Rosalind the happiest possible birthday for years.

Yours sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Very many thanks for the cheerfulness in your letter this morning (it is dated April 4th). I had wondered how you were going to retain further hold of 'Clovelly' after this visit from Rosalind and Mr Akin, and now I know! If you run out of ideas, in the early summer when they motor over, no doubt you will be able to claim that they might have a smash on the road and it would be better to leave the picture until they walk home . . . . . . !

. . . I told you last week, did I not, that I had been to see the film of Anastasia – yes, I am sure I did, and went on at great length about that fascinating creature, Yul Brynner. Well, in one scene in it he was making Ingrid Bergman walk about with a book balanced on her head, because the Grand Duchesses of Russia were noted for their deportment. I have always found it quite easy to balance a book on my head, but the other day I remembered this scene, and promptly stuck one on top my top-knot. And there I was, standing thinking in the window of my office (it was after hours, in case you wondered) when I suddenly realised a very surprised looking man was standing on the other side of the window, looking in. Rude creature. I took my book off to him, and he moved off hurriedly.

. . . Last night I visited some friends, and while there, they had their television set on to see the Queen attend the dinner in her honour, at the Louvre. It was rather sweet. The French Government had written to England giving a list of the best paintings in the Louvre, and asking which the Queen would like to see. She had chosen a dozen. They then built a smallish room in one of the Louvre courtyards, next to the gallery in which the dinner was to be held, and lined it with pale blue curtains, on which they hung these paintings for the Queen to see while she waited for dinner. There were enormous bowls of pink apple blossom about the place, and lovely furniture from Fountainebleau. And, being French, they added to those paintings the Queen wanted to see, a couple by Degas showing horses! The Queen, seen through the camera, seemed delighted about this. She went round the others quite sombrely, accompanied by the Minister responsible for Art in France, and coming to the end, the President, M. Coty, came up to her and, suddenly, the Queen was lit up – lively and loquacious and full of spirits. She bent toward M. Coty, who bent her way, too, and whispered something to him, then they both roared with laughter. From the camera position we could see the Queen making very Gallic gestures with her white-gloved hands and arms – including a sort of dog-paddle with her hands and arms in front of her, as though she were describing how a dog used his paws in begging – or perhaps one of the racehorses she had seen that morning, and how he pawed the ground . . .

Mother, last night, looking at my arrangement of red tulips and dark green rosemary in a shallow turquoise bowl in the living room, 'Those carnations look just like roses, dear.' . . .

I daresay this letter will reach you before Easter, so here is my good wish that it will be a very happy one for you, and now that Lent is nearly over, your haircloth shirt will leave you in unirritated peace once more.

Most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . On Sunday Mac asked us to go for a drive, and once we were out with him it appeared he was due to take his girlfriend out too. I have more than a suspicion he is trying to disentangle himself, because she was most annoyed at seeing Mother and me in the back . . . we had to pretend an aunt was due at our house for tea, so that he had an excuse for not inviting Mary home as well! Later on in the week he said to me as he went out one evening, 'If you-know-who telephones, tell her we're going away tomorrow and won't be back until late on Saturday evening, will you?' Yes, everything points towards disentanglement. Mac's trouble is a) he will fall for a pretty face, and b) most of the girls he knows are ghastly little snobs to start with, and a) so blinds him to b) that by the time he notices it, the girl quite likes going about with him. Eligible males are as rare as purple diamonds, in Bournemouth.

Anyway, that was Sunday. On Monday we took Mother to her old honeymoon haunts in North Somerset. It was 49 years since she was there, and the dear soul kept saying, 'Oh – that's new!' as we passed cottages or shops or bus shelters. Quite likely she was right. We had a picnic lunch on top of a very high hill with glorious views, as I believe I told you before, but I don't think I mentioned the fact that we were surrounded by little skylarks nesting and darting about and singing their little heads off. Nor did I tell you that as we sat at our meal a young man came down from the peak of the hill, and swung by us on his way down the rest of the 1,700 feet into Porlock. Nothing unusual in a young man, with rucksack on back and stick in hand, walking up and down Exmoor, I daresay. But this young man had a wooden leg . . .

Friday. Friday we took Mother to Lyme Regis, and it was fine all the way, fine there, Mac played golf with a cousin and a cousin-by-marriage and somebody else, and Mother and I sat and made polite conversation indoors. Saturday it was work again. Sunday afternoon I took Mother to Blagdon Heath for a picnic and to paint, but the sun went in, and the view was so immense from the top of the hill I didn't even attempt to paint it, but went scrambling down the hillside in my stockinged feet (shoes are too slippery on steep grass) and picked stinking purple iris and golden cowslips and read Lord Chesterfield's letters to his son. And so home, to wash my hair and tease the cat and so to bed.

Monday followed all too quickly and I now no longer feel I have had any holiday at all. I really must make up my mind to have one at the end of the summer, and not act as chauffeuse to all and sundry most of the time.

To finish. Mac is, as perhaps you know, honorary secretary of the Bournemouth War Memorial Homes (instead of a Memorial the money was spent building special houses for disabled ex-service men).* He gave this voluntary work up while he was swotting for his exam, but this week took it up again. Reporting the Minutes to the Committee, he took the chance to say how sorry he was to learn of the death, in January, of an elderly member of the Committee. Another elderly member said, 'Ah, dear me! So that's the reason I haven't seen him at Committee meetings lately.' The Mayor, in the Chair, said dryly that it was an excellent reason . . . . . .

* Editor's note: Years later, in 1991, Frank MacPherson Woodsford received an M.B.E. for his voluntary work for the Bournemouth War Memorial Homes. Frances went with him and his wife to Buckingham Palace.

Thank you very much for your letter, which broke the long drought of letters to No. —. I was so glad to hear your penicillin troubles were leaving you, and the sooner the better.

So, au revoir until next week, and I hope you keep very well until next time I can make you that wish.

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . If ever – perhaps I should put ever in capitals – If EVER I go to Heaven, Mr Bigelow, it will be mainly because I was known to have taken my mother for a car drive at least twice a week without once hitting her! I took her, and a widowed neighbour, out last evening. Mother, to my left, kept up her usual running commentary on the names on the signposts – not the places we were aiming at, but those down the roads we weren't travelling; and lots of oohs and ahs and looks! all along the route. All aimed at me, for of course when I am present no conversation can possibly be carried on unless I am the centrepiece. That is obvious. And in the back of the car Mrs Nixon, doing exactly the same sort of thing – only she doesn't call out wrong names from signposts, thank goodness. She merely talked at me non-stop, and on subjects completely different from those Mother was currently engaged in. At one point I was in such a tizzy I near as dammit stopped the car and said, 'Now let's have a cosy little chat, shall we? And then, when we've got it all out of our systems we will proceed, leaving the driver just enough peace to avoid killing the lot of us!!' But I didn't, and for that, as I said, I expect my reward hereafter. Here, they just drive me insane. My mother you probably find quite unbelievable: I know, most of my friends do, but when they meet up with her they find she is exactly as I have described . . .

Mac goes on holiday tomorrow. It is raining and dull and cold today. We are praying it will be better tomorrow, for this is his first holiday for many years. The removal of petrol rationing has come just in the nick of time.

My boss is away today, thank goodness. He is not well, and his temper terrible, and yesterday we had an overnight flood and half the building was under water in the morning, and Mr B. practically exploded! Thank Heaven I was at the dentist's and therefore missed the first full blast. Thank goodness, too, I had made such a fuss about the water cisterns in the toilets for women that the engineer had put them all in order only the day before – for the flood was caused by a ball-cock breaking off in the men's toilet on the first floor and, this building being so beeeautifully designed by a London architect who doesn't have to run it, that all our toilet overflows go, not out through a drain or even down the toilet itself, but straight onto the toilet floor. Thence, under the doors and down the stairs, across the hall, into the cash office, my boss's office, my office, down through the tiled floor and more stairs and into the basement storeroom, where they just about ruined all the tickets for our water show and three dozen brand-new bath towels which were on the top racks in the store. Oh yes, and all the nice new posters we had done specially to last us through the summer and next winter. This is the second flood due to faulty building design we've had – the other was at Christmas when I ruined my best shoes wading through for help. Yesterday I paddled about in my next-best shoes and you can guess the result!

Ah well. More next Saturday if I haven't drowned in the meantime. I hope you are well, and enjoying all these visits from your grandchildren and great-grandchildren. You should never let a great-grandchild get within reaching distance of a bottle of ketchup: it's a lethal weapon, didn't you know?

V. sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Thursday evening, and I daresay my brother will be very late, this being his boss's first day back after a holiday. So she will trot into his office at 5.14 p.m. (they shut at 5.15) and sigh heavily and start telling him what a terrible time she had all through her holiday, and I shall be fuming up and down the pavement outside here for nearly an hour, I daresay. So, to rest my shattered nerves a bit, I am instead, getting on with something much more useful than pavement-pounding ever could be – writing to you. I am also yawning my head off with the stupidest nerves, as this evening I am to see my doctor and have every intention of talking him out of this silly visit to the hospital next Tuesday, re appendix, which I am positive I do not have. How, my problem is, to tell the doctor he's wrong, without offending him?

. . . Since my last letter, History has Been Made. I met a young (about 25) Spanish student, a graduate in Political Economics who is studying English with a view to entering the Diplomatic Corps, and after chatting a while – mostly, this consisted of a well-chosen question from me followed by a fluid outpouring of words from him, at which I nodded sagely and hoped for the best – after chatting for a while we shook hands, and whilst mine was still in his, it was raised to his lips and kissed! My hand, Mr Bigelow! Large, square, rough, scratched, and useful. But certainly not the kissable type; nor yet the inspiration of poets or song-writers. No, definitely utilitarian. I trust that in future you will be more flowery in your letters, to suit such a romantic lady as me. None of this 'Hi – you!' business in future, please . . .

Now I must get this away. I hope you continue to keep well and avoid taking any more rides in the Dalls' new open tourer – unless you hide under the floor mat at the rear, that is.

Yrs most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

First of all, to get it out of the way – I went to the hospital on Tuesday, spent all of three minutes with the specialist, and he patted me on the shoulder and told me to run away. Or words to that effect. So all is well. Apparently I have what the man described as a 'resistant tummy'. Daresay I am fossilising a bit ahead of time. Now I am taking all sorts of horrid tablets I have bought myself, to get rid of the throat trouble. I am still losing a little weight, not much, but a little, and that is a worry and until I have resolved my own mind, the loss will probably continue.

The trouble is: what job to do, and where to do it? There is this local job I have been offered. Then there is utter misery at work just now. My brother is most unhappy under his boss, and this morning in the car I tackled him, telling him I had heard rumours that he intended staying only another two years and then moving elsewhere – was this true? He said it was. Where would he move to? He shrugged, taking both hands off the steering wheel to gesture Gallically as he did so. Abroad, perhaps. So that's that. In two years' time I shall be left here, with a misery of a job, and Mother, and a cheap flat. Eventually, if he goes abroad, I dare-say Mac will marry, and Mother will fade out of the picture one day, and that will leave me with a cheap flat and a misery of a job in a town which is clean, healthy, in pleasant country, but one which I personally dislike very much to work in.

So, today I am racking my brains as to the best for the future. It frightens and dismays me more and more. But if I am to do anything at all about it, it must be soon, while I am still young enough to be able to adapt myself to some other kind of work. Today I am toying with the idea of telephoning my uncle about that tentative job in London about which I heard second-hand rumours last autumn. London beckons me, as you know, a great deal, and I should love to work for somebody I respected for a change. In two years, perhaps the housing position would be a little easier and, if Mac did go abroad, I could get a flat near London and Mother could join me there. But these next two years would be very difficult, with living so much, much more expensive away from home, and home expenses to meet as well, and the car to pay for on top of the rest. But it could be done, and my problem is, should it be done? I, too, would like to go abroad – there was an advertisement for secretaries to the Government of Tanganyika in yesterday's Telegraph, but they are only for three-year contracts, and that might leave me high and dry at the end, if I didn't like it, or it me. And then, too, I have to think of Mother: she obviously cannot be left alone. If Mac goes away, she must either go with him, or come to me. Or I must stay here against the day when she will be too frail to look after herself. So I lose weight, and do you wonder!

Never mind: let's off to pleasanter subjects – but thank you, just the same, for your offer of a second-hand, slightly split, appendix in case I might have any use for same! Is yours pickled in alcohol or did you intend sending just the old ruin all that way by itself ?

. . . We have been reading of your great heat in the papers recently, and I was just about to write to Rosalind and sympathise with her, for if it was 87o here, and 97o in New York, it would be even higher in St Louis – and then I saw a headline in the newspaper about the torrential rains and floods they had suffered in St Louis, so that was that. Do you sit at the bottom of your garden and dangle your feet in the water? Or is a) the sea too far below the level of the garden, or b) your leg too short? I don't, you will notice, put 'or c) are you too dignified?'

I want you to read the little letter I cut out from a paper first, before you read this paragraph. Ready?

Daily Telegraph Press Cutting

Bees can show gratitude.

Some years ago I was bathing off the Belgian coast when I came across a bee swimming in the sea. It was quite obvious it could never reach the shore 200 yards away, so I put my arm under it and it clambered on. I then walked out on to the shore and waited while my arm and the bee dried out in the sun. A dozen people stood round me watching the bee drying itself and straightening out its wings on my arm. After about 10 minutes it flew 200 yards or so away, then suddenly turned and came straight back to me with all the other people still standing round.

To everybody's astonishment it circled very closely round my head three times, then flew away.

V.W.H. Venour, Junior Army and Navy Club, Whitehall, S.W.1.

I asked you to read it because I can't now find the other letter, which appeared a day or two later. This one said, in effect,

I read the other day of a grateful bee, and to show that bees aren't the only insects to show gratitude I am telling you of an experience of mine, with ants. I found an ant one day labouring under the weight of an enormous seed. I picked the seed from the ant's back, and following the insect to its hole in the ground, returned the seed to it, whereupon it grasped it and hurried down to the nest. Imagine my surprise when, a second or two later, a long line of ants ran out of the nest, and forming up on the grass, spelled out 'Thanks, pal'.

And as I cannot think of a better line on which to leave you this week, I will do so now and stroll over in the sunshine to post it.

Yours v. sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . We had an official form from our landlord this morning, notifying us that our rent is to be increased by about 50%, under the new law just passed. Mother and I discussed it, and then, as we had agreed, Mother 'phoned the landlord and said we'd had this form and thought it was extremely fair and we were very relieved, as we'd felt awfully guilty for years at the low rent we were paying, and restricted to paying by law. There was quite a pause at the other end, and then the landlord said, 'Mrs Woodsford! You've no idea what those words mean to me!' Poor man, I think we must have been the only tenants he has who had not either telephoned abuse, or immediately consulted a lawyer, or rushed over to shout at him in person. Far be it from me to wish that we were paying a rent as high in proportion to our joint earnings now, as we did before the war, but we haven't been paying anything like an economic proportion, and although we haven't, of course, asked the landlord for any repairs or decorations, our hearts have smote – smitten? – us quite a bit. Now we feel better, and so, apparently, does the landlord . . .

Yours v. sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

A midweek letter to console you a little for Rosalind's so short a visit, leaving you high dry and, no doubt, handsome, behind. + Never mind: no doubt you are getting busy for 'Race Week' and all its concomitant social occasions and busynesses. I hope you have better weather for it than is currently plaguing us, for today it is wet, wet, wet and at work we are swamped, swamped, swamped. Damp babies, damp mums, dads with everything about them damp except their language. And, of course, insufficient staff.

There is a cream-coloured flag out in the Bay, flying alongside the buoy that marks the end of the town sewer! I suppose this means Poole is having a Yachting Week, or perhaps Christchurch. Or, who knows, Bournemouth might. Bournemouth suffers from having a wide beach, perfectly safe for swimming, being all sand for its nine-mile curve, but having no anchorage whatsoever for boats or ships, which have to up

+ Second reading suggested the removal of this one word!

anchor and run for safety if any wind at all blows, for they are either blown onto the beach, or out to sea . . . Poole has an enormous land-locked harbour, second only to Rio in size, but very shallow. I haven't been around it myself, only looked at it often from the viewpoint on nearby hills, but it is an extremely beautiful harbour. Mac was there only last Saturday, taking his 'family' on their annual outing in Bolson's boats. 'Jake' Bolson is the son of a man who started off with a dinghy, and died owning a fleet of ex-Naval craft; a boatyard; a couple of shipbuilding factories, and several other worthwhile properties. But they still put all their pleasure cruisers at the disposal of the crippled children, the orphans and Mac's lot, once every year, and a high old time is had by all.

Last Saturday when he got home Mac said he was one short at the final count, but that one might have slipped behind his back while he was talking to somebody who had come up and tapped him (Mac) on the shoulder. Or, horrid thought, the missing one might still be in the lavatory! We thereupon started telephoning all Bolson's numerous telephone numbers in the book, to ask whoever answered if they had found a small boy locked in somewhere. They hadn't, luckily. Mac asked one child how many free bottles of pop he had drunk, and when it turned out to be six, Mac said he was glad the Bay was so choppy they stayed inside the harbour, and merely cruised around the islands there. He also said one child was showing off a Scout knife, and the ship rolled, and the child did likewise, and narrowly missed gouging out the next child's eye. What fun we do have in our jobs, don't we?

. . . Thank you for your nice letters, too. I look for the postman every morning, you may be sure.

Yours most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . My brother has a new girlfriend – probably she's 'one over the eight' – and she lives in a very elegant part of the town, in a house just on the corner of a road we pass in the mornings, on our way to work. So Mac has an arrangement with her: she stands at a window, possibly elegant in a peignoir or other sort of frills – and waves to him, and Mac waves back. But, of course, his sister musn't know about this, so he just puts his hand out the window on his side of the car, and turns it up, and waggles his fingers over the car roof and she sees this as she stands at her upstairs window on the far side of the street from Mac!!!! I met her last weekend: she was quite pleasant, although with a rather better opinion of herself than I thought quite mete to display at first sight. She is nearer Mac's age, which is a change, and I think it quite possible that her awful situation at the moment is playing on his sympathy – she has a hole in her heart, discovered only last year, and the doctors are trying to build her up in strength to enable her to come to America next year to have a very dangerous operation: otherwise she will be a complete invalid in a few years. So apart from being reasonably pretty, and extremely well dressed (very rich father, which helps!) she has this tragic sword of Damesthenes or whoever he was, to make her even more romantic.

I trust you have made your peace with the Dalls by now, which reminds me: I have asked so many favours of Mrs Dall I would very much like to send her a little gift, to thank her for all her help in a more practical way than just by letter. Do you know of any hobbies she has? Or does she collect anything? Don't say 'Yes, Dresden China', please, I just couldn't bear it. Something fairly simple to find. I should be most grateful for your help in this direction.

Mother is – she says – going to win a competition in which the prize is £1,000 and a weekend flying trip to New York: just fly there Friday, and fly home Monday night. If she wins it – and she has been going to for 35 years, now, without quite managing to do it in the present tense – if she wins it, she will give me the trip to New York, so please have that spare room ready, as I should disdain being taken on a sightseeing trip to Radio City on the Saturday, and to Niagara on the Sunday. Waste of time: I'd go and have a look at the Long Island Railroad. Much more interesting, I am sure.

Yours v. sincerely,

Frances W.

Bournemouth September 14th 1957

Dear Mr Bigelow,

The sea within the lee of the pier is putty-coloured, and the top surface is corrugated into small wrinkles on rather large, oily waves. But beyond the pier end, it is deep green and dark blue, in lines, with white horses tossing their proud mains + like mad. In other words, the wind is blowing and the clouds are rushing, and the fall is upon us before we have had summer – for we only had a lovely warm long spring. Summer just went down the drain.

To celebrate the end of a horrid summer, I have had my hair waved again. I went to the hairdressers, and as the man stood behind me, scissors poised, I said, 'You know, I have always wanted to have my hair up, in a bun.' He at once gave a vicious snip at my head, taking a handful of hair away with his cutters, and said firmly, 'Now you can't have one.' So, being thwarted once more (I would love to look fragile and ever so feminine with a big bun) I said airily very well, he could do what he liked with my hair, and I would not grumble. And now I am mutton dressed up like shorn lamb, and only the fact that I can't sing, even flat, stops me being the twin of Mary Martin in South Pacific.

+ well, it's water, isn't it?

Anyway, I wore a lovely new dress (from the usual place!) next day, and knocked the office staff cold. I was emptying something in the big rubbish box behind one of the hall counters in the morning, and the hall man was there doing something with a mop and bucket. He leaned over, and put on the electric light, and said confidingly, 'I hope you don't mind me saying so, Miss, but I do like the hair-cut.' I must say I like it myself, especially at night when it needs no setting, and in the morning, when all I have to do is to run a comb through it (plus a little of those feminine touches which are said to have such a whale of a difference on anything) and, at a pinch, I could manage by running my fingers through it. At this stage, in the blissful honeymoon as it were, I do not think about how quickly it will grow out and need waving again! Or, if I do, I quickly thrust the thought from me under the carpet like a bill . . .

You know, Mr Bigelow, I am beginning to wonder whether Mother's general daftness isn't hereditary, in which case I shiver for myself. My mother's unmarried sister has, at long, long last, been able to find a tiny two-roomed flat for herself, and has moved in, to the accompaniment of dozens of letters to all the dozens of members of the Mould family. We were invited to motor over for a flat-warming, and correspondence has been flying to and fro about the possible date. My aunt gave us a list of weekend engagements she had, the last of which is on the weekend of the 21st–22nd September, so we wrote back and said we'd go over on Sunday September 29th. In the meantime we had a postcard from some cousins who live on the way, saying how pleased they were to hear we were going over on Sunday the 15th and would we call in and see them either going or coming. We wrote them and said it was the 29th. Auntie Ethel wrote and said how surprised she was we weren't coming on the 22nd! And now she writes to say it is just as well we aren't, as the previous engagement she said she had, seemed still to be 'on', so she was looking forward to seeing us on the 27th. (That's a Friday) and by the same post, Cousin Arthur writes to say sorry he won't be home when we call as he is going to Cheltenham on September 38th for a week. I cannot help but feel that the Mould Clan use some special kind of calendar, not related in any way to the Gregorian. The sort of calendar, indeed, that I myself use when calculating when to visit my dentist for my six-monthly attendances. However, we have now fixed the date and have plenty of time to prepare . . .

Yours most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

It is now Thursday, midday Thursday, and I am breathing normally again – you know, in-out, in-out and so on. Up to now, I have been going iiiiiiiiiiiinnnnnnnnn-o't with a terrific gust, owing to a little amount of trepidation or blue funk over having to take the Committee meeting this morning, in the absence of my boss. But now all is over; the boys have scattered, nobody bit me, and I even managed to drink a cup of coffee with the others, without taking a chip out of the cup with my chattering teeth. Coffee, I may tell you, is served to the Committee before they get down to business. By the time the meeting was over, I was so cocky I asked if anybody would care to see the newly-decorated Turkish Bath – and the whole lot came. So I described the proceedings to them in my best manner, and they were suitably impressed! I got so self-confident I even invited one Councillor, afterwards, to see the plant, which he had said he wanted to see. Unfortunately for me, all set to give my little lecture on Water Filtration In One Easy Lesson, we bumped into the engineer in the first room we went into, and he took over. However, if he did spoil my limelight at least he saved me from getting into a mess, for the Councillor concerned is a B.A. and Doctor of Philosophy and kept asking awkward questions about chemistry, on which subject, as you know, my knowledge is absolutely nil or even more so.

So now I feel relaxed and definitely reduced in tension so that I can waggle my head (if I feel like it) without the top coming off. And I can concentrate for a while on writing to you . . .

Very sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . This time, quite casually, in the garden on Sunday, he said to me, 'Oh, by the way – I would appreciate it if you wouldn't talk about Audrey to Mother too much. You know I'm very fond of her; I should really like to marry her but I don't suppose anything will come of it. Her father is a sort of Mr Barrett, and won't allow a man in the house – he wants everything to go on exactly as it is.' So saying, he strolled back to the flat leaving me outwardly serene, and inwardly aghast, so that I have worried and worried ever since . . . Father is very wealthy, and judging by the look of Audrey my brother couldn't keep her in hairdresser's bills, let alone make-up or clothes. Or, Heaven help him, doctors' bills.

I have a shrewd suspicion that my brother is incurably romantic, and this early-Victorian father, coupled with the heart business and the glamorous blue eyeshadow, emphasising the invalidism, has played on his sympathies and feelings to such an extent that he sees himself as a knight errant rescuing fair maiden from wicked uncle (or Frightful Father).

My problem is this: Mac keeps talking about jobs in Rhodesia and Nyasaland and so on, presumably with the idea of marrying the gal and carrying her off on his snow-white steed. Do I help by going off to London and getting a job there and, Heaven help me, persuading Mother to come up with me if I can find anywhere within my pocket, to live? And so leave Mac on his own, with the incentive to launch out for himself. Or do I just sit pat, and await events? If I do, and nothing comes of this marriage business, I suppose I just sit pat again until I am too old to do any launching out for myself. I cannot, try how I may, visualise my brother getting up early and cleaning the grates and pre-paring the breakfast because his wife is an invalid. It just isn't within the realms of possibilities. Nor can I see Audrey, who is quite a pleasant sort of person, getting down to life on Mac's salary . . . but maybe I'm not being kind nor sympathetic enough. I am all mixed up.

It would obviously be impossible to live with my brother after he married (if ) and certainly I would not keep a job and run a home for him if I had also to look after his semi-invalid wife. But the trouble is, that in our family we have always looked after each other, especially so where Mac is concerned. Another point which worries me is that if I do go away, from what she said last time the subject was broached, Mother wouldn't come with me, but would stay on in the flat by herself. This inevitably leads to the question, what would I do if she was taken ill? Oh dear, oh dear: no sooner do I pull myself out of one slough of despond than another looms before my feet. Don't think I am grumbling about all this, Mr Bigelow, for I am not: it's too important for a grouch, it really does worry me; and I know it's important because Mac is treating me as though I had to be consulted on every point and my wishes considered all the time, something which is quite abnormal for that young man . . .

Most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

What, in spite of the date, a birthday gift did I get from Bellport today!! Never have the seven floors of Beales* been so disrupted, I am sure, as they were today in my lunch hour, when I tottered around, practically drunk with delight, and chose my presents from you. Everybody was most kind and helpful, and chased me all over the building as I did one thing wrong after another, all due to the fact that, as I pointed out, I had never had a birthday gift like this one before, and must be allowed, and expected to mess their organisation up a trifle. So they beamed, and said of course and how wonderful for me: in fact, they seemed to enjoy it almost as much as I did. This is a list of the enormous variety of presents you gave me, and how you knew exactly what I wanted, I shall hardly ever know:

* Editor's note: Mr Bigelow had sent a gift of credit to be spent at Bournemouth's department store.

First, I had decided, as I told you, on a wristwatch. Then today I decided against it, as it seemed to be more fun to spread the gift over different ideas, and not keep to one thing. And it would have had to be one thing, for while I quite liked the very cheap watches, I should not like to waste your money; and those a step above the very cheap ones I disliked intensely; and the step above that would have taken all the cheque, and that, as I said, I didn't wish to do. So first of all I went to the linen department, and hummed and ha'ed over the blankets, green and yellow, thick and honeycombed, with and without satin bound edges. In the end I fell for an extremely thick and fluffy pale green blanket, with satin edge and a big bow to show it was a present. That was No. 1. Then I picked out a feather quilt in Paisley pattern in green with peach. Then I tottered downstairs to the jewellery counter, where you gave me a lovely shiny black, round powder-compact, with a tiny circle of marcasite flowers in the middle. No. 3, that was. Next I chose a marcasite ring: I liked most of all an oval black stone with a surround of marcasite, but it only fitted my little finger and I don't like wearing rings on that one. So I picked out, instead, one all marcasite on silver, with an intricate effect of slender strands woven in and out and over and under each other. They tried to get me to buy what they said was a cocktail ring (why, I don't know: it was an eternity ring masquerading under an alias) but it was so big it would have done very nicely for a knuckle-duster, and I don't move in that sort of circle.

Next I moved over to the cosmetics counter where I frivolously bought a bottle of pale cream-coloured mud – you put this on to hide the fact that your skin is naturally putty-coloured mud – and some lip stuff and powder, and a little black and white case to hold all this neatly in my handbag.

After this, weakening slightly, I went to Gloves and chose a pair of black kid lined with wool, for the winter. And finally, after adding up all the others and doing mental sums in a sort of daze, being bumped into by the other shoppers, I went back to the blanket department and added a large flannelette blanket. This is for Mother, and I'm sure you don't mind, but I wanted her to share in my good fortune, and my brother was already accounted for as he will have my discarded quilt and a travelling rug which your green blanket replaces . . .

Yours most sincerely and overwhelmed,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . Quite casually, as we were going home on Thursday (applications have to be made in December or forever hold thy peace) I asked my brother if he'd applied for regrading (one way to get an increase in salary). He said no, because he wasn't at the top-rate of his present grade yet. Had I? This, because I had said I would do so, back in the summer when I was working around the clock. No, of course I hadn't, and the letter had to go before the Committee the very next morning. So I dashed something off that evening, and put it on my boss's desk. He was much taken aback, and very dismal about my prospects, but cheered up a bit when I said I would neither resign, nor sulk, if I was turned down as I fully expected to be, as I never could put my heart and soul into such a letter in the middle of winter, when I wasn't earning my salary anyhow. And, in the event, the Committee were apparently all in favour of it, and of me, and all sorts of nice things were said about yrs trly (which I am not supposed to know about, but heard in a roundabout way through friends at court) and I shall either get a £30 rise next spring, with another £20 the following year, all of which would count as salary and for pension calculations in the event of my living that long; or if the Establishment Committee – a real tough body of men – turn it down, I am to put in for over-time pay, which I know would come to more that £50 a year anyway. So either way, I shall be much better off next year. This is certainly being my year, isn't it?

First of all, I had that enormous birthday present. Then I had my aunt's fur cape, which has this week come back from the furriers made up as a stole, and looks a million dollars and quite unlike me. I just drip silver-fox like Peggy Hopkins Joyce only without so many husbands. One of these days, the occasion to wear the fur will come along, and then a few pairs of eyes will be knocked out of focus, believe me. I am not at the moment sure about hay fever, never having worn silver fox before, and getting a bit mixed up with hair in mouth, hair on tongue, twisted around back teeth, tangled with my eyelashes, and inhaled into my nostrils. However, with a bit of practice I shall grow a longer neck and that will take me out of the danger zone.

Then on top of all this, the Committee business. All I need to finish off the year, is to win a Football Pool and become, overnight, rich enough to wear the fox fur every single day, just for popping down the road for cat-fish.

And the police sent me three canvas-boards to paint on, as I still insisted on 'being stubborn and silly' (their words, not mine) about not taking money for what help I give them on the occasion of their annual swimming gala.

I can't for the moment think of anything else anybody has given me, not even a high-sign or the glad eye or the go-by, but if I do before the end of this letter, I will add it to the list. Quite a formidable list of nice things, I am sure you will agree . . .

Yours most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

. . . We had our first carol-singers this week. A reasonable government, some few years ago, passed a regulation forbidding the singing of carols before the first week in December. Up to that time, the trend was, go around collecting for Guy Fawkes' night, and immediately that is over, swing into your carol-singing. Anyway, I was at home after dinner, and the radio was on and Mother was banging away in the kitchen and the cat was snoring, when suddenly there came this singing from outside the front door. Loud and clear it was. It is quite difficult for carol-singers to make themselves heard in our upstairs flat, especially when our radio is going, but this lot could be heard halfway to Dorchester.

I got some money, and after a verse or two, trotted downstairs and opened the front door to give it to the singers – and there, with his little mouth almost in our letter box (the better for the sound to carry) was a small urchin of no more than nine years. Singing away at the top of his voice, with his little red gloveless hands in his pockets! Usually, we get so many little groups, that we make a rule to give twopence each, but I had gone down with sixpence, expecting at least three small boys. And here was one single little singer, with all that power! I gave him the sixpence, and congratulated him and said he'd do well because even without a brass band to help him, one could clearly hear his concert. He wiped his little nose with the back of his hand, tucked his sixpence in a spare pocket, put his hands back, and rushed off to try the next house. Mother was annoyed: apparently when she was young the carollers gave you some more singing when you had paid them; nowadays, what with automation and time and motion study, the minute they are paid, they're off. Could it be that most carollers have little faith in the voices they throw at one?

Thank you for your letter (Dec. 3rd) from which you sounded more cheerful, and more spry, than for months past. I was very glad to read it, but I took your remarks, about Devonshire cream making you sick, with a grain of salt which you may imagine quite spoiled the taste. However, I hardened my heart and refrained from rushing another order to Devon for cream for Christmas for you, as you will no doubt go to a dozen or so (nothing much) cocktail and other parties, and if you don't, at least I must look out for your figure, sire.

There's been a spate of writing in the newspapers this week, on the theme 'Don't be nasty to the Americans'. Nobody I know has been particularly nasty that I know of, so I can only imagine the snide remarks about the rocket were made by newspaper people being clever with words, for the sake of cleverness and without any consideration for the effect of their wit. We most of us feel that America did give too much optimistic publicity to her efforts beforehand, but that is no more than you feel yourselves; and the nasty shock to the nation as a whole is much too important to be sniggered at. So take no notice of the news-papers: they just love stirring up ill-feelings, as you know. There has, on the other hand, been a certain amount of – I won't say anger, because it wasn't heated, but dismay is perhaps better – dismay at the news, quite unexpectedly wangled out of the Prime Minister, that American 'planes are flying over England in practice, with atomic bombs in their racks. That is an uncomfortable feeling, for coming right now, the assurance that nothing can go wrong doesn't altogether have the reassurance it might have had, had nothing gone wrong in Florida.

And now, this week, I will indeed wish you a very happy Christmas, and a very happy New Year with no repetition of last year's hospital todo and kerfuffle. From the newspapers I fear your prophecy as to snow has been more than fulfilled, but just the same I hope it didn't handicap your visit from Rosalind, nor stop you going out and about whenever you fancied.

Very Happy Christmas, dear Mr Bigelow,

Most sincerely,

Frances W.