1961

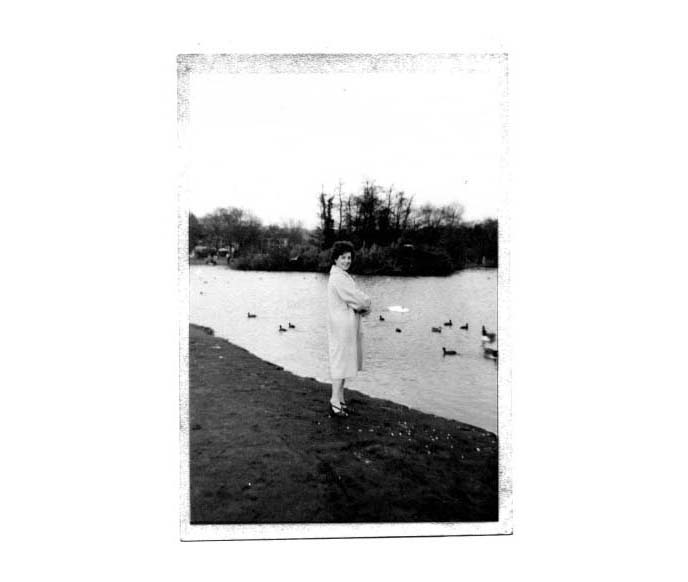

'Lady Bountiful in Poole Park. I always use Yummo Face Cream: that's how I manage to look 17 when actually I am 18 1/2.'

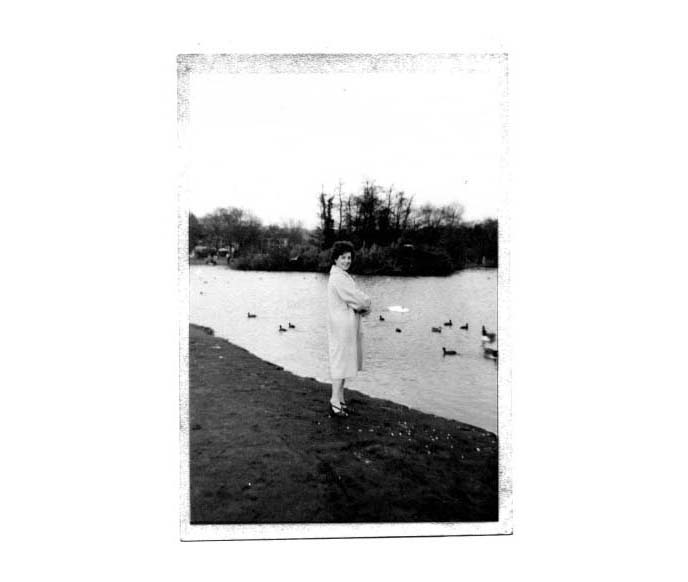

'Lady Bountiful in Poole Park. I always use Yummo Face Cream: that's how I manage to look 17 when actually I am 18 1/2.'

Dear Mr Bigelow,

At first sight I thought my newly decorated bedroom was going to be a major disaster, like illegitimate twins, but in the end it turned out not too badly. Not a success by any means and I still can't imagine why I chose pink, a colour I detest, for my walls. Ah well. At least, I did in the end bring about a marriage between the walls and the ceiling . . . . . . When the walls and ceiling were done, the grey paint on the picture rail suddenly turned from being grey to being turquoise and looked absolutely unmentionable. I washed several gallons of pink off myself and dashed down into town to change the second tin of dark pink for mushroom. Painted the picture rail mushroom, and the door pink with mushroom frame. The skirting board, too. And that was as far as I had got in last week's letter. I left the window frame until Saturday afternoon. My windows suffer badly from condensation, but before starting to paint them I wiped them down with a dry rag, to remove the last of the damp spots; took down the old curtains and the net ones, which I washed. Painted everything mushroom. Looked quite nice. Waited three hours, and then put up the net curtains and made and put up the new green ones. Result – it looked like something in a shop window, and on going to bed that night in my bright pink fluffy nightgown I felt like something in a shop window, too – say a French pastry . . .

And then Came the Dawn, as alas, it always does. I looked around me, and thought sleepily, 'Now why can I see those black damp spots down the centre of the window?' and, when I climbed out of bed, I noticed that not only could I see the old damp spots, but the paint was almost grey, and not mushroom as it had been when I went to bed. On looking with horror, more closely, I found that my nice matt mushroom paint had run all down the metal parts of the window; formed little puddles of mushroom paint on the sills, whence it had been greedily sucked up by the net curtains. Oh, comme j'étais fou! [sic] That means I was up you in French. Mad, mad, mad. I tore down to work, where the painters are at work in the hall using the selfsame paint, and complained bitterly at them. The senior one laughed, the creature, and said now I knew better than to use a waterpaint on metal work, and, worse still, to use it while the metal was frosty. I am now waiting for the spring, when a) we shan't always get frost, and b) we might not always get condensation either. Whether we shall avoid both at the same time is another matter, but in the meanwhile I have one strip of grey paint and the others are mushroom and the curtains are permanently fringed with brown. Why do these things happen to me, Mr Bigelow? Do you think it is an evil spirit, a sort of personal gremlin or jinx perhaps? I feel myself the object of a malicious vendetta, and if only I knew who was behind it all I'd give 'im something to vend about.

Do you ever get noises in the head, Mr Bigelow? If you do, you have my heartiest sympathy because I do, too, and a darn nuisance they are. I remember one night early last summer jumping out of bed about midnight and hanging out of the window to shout to Edwin Ridout and tell him to stop revving his wretched motorbike all night outside my home. Only to find everything was quiet, and it was me all the time. This eventually passed, but it came back before Christmas and has been with me, on and off, for about six weeks now. It's a thorough nuisance at night, when it wakes me up and also prevents me getting to sleep for a long time. I have tried warm olive oil in the ear; knocking myself on the side of the head, shaking it, turning over, blowing down my nose whilst pinching it at the nostrils. Oh, everything but going to see a quack. At times it even goes on so loudly that during the day it gets between me and my work (not that it requires anything very thick to do that) and at home in the evening it is sometimes necessary to turn the radio on to drown my other row. It wouldn't be so bad if the noise wasn't so darn monotonous . . .

Mac took me to the social and dance that this particular Evening Institute held last Friday, and as we came away rather before the end I muttered 'Dit, l'oiseau noir' which is my French for 'Quoth the Raven'. Trouble was, not enough people knew each other, and there were not enough masters-of-ceremony to make people get to know each other. And, of course, the refreshments being cups of tea didn't help the social atmosphere. And Mac was cross, because it was his night out with the lads and he'd given it up to escort me, bless him, and this was what he got – a couple of dances with his sister, and a cup of tea and a bun! He also got in a mix with two very small girls, ages being about seven and eight respectively, whom he drew as partners in a sort of Scottish dance where each man has two ladies as partners. To see Mac going under the arch made by his arm and that of his partner, first on one side and then on the other, was very amusing, and quite the highlight of the evening . . .

It is a glorious sunny day today, and so far, the Jonahs who predicted a cold harsh winter have been eating their words. Looking to my right, on my windowsill is a pot with a blue hyacinth in it, and a pot with red cyclamen, and then a dirty windowpane and then sunshine everywhere, reflecting back from the water and drying the pavements which got soaked, along with me, last night.

And now to say au revoir until next Saturday. I do hope you are obeying my behest, and enjoying life a little bit more. Summer is not far off, as I know from the urgent preparations now going on for our next water show, curse it. In the meantime, stay snug and warm in what I have else-where described as your sea-edge home.

Yours most sincerely,

Frances W.

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Last evening, as I walked across a short section of public gardens, I looked around me, as I wanted some dead twigs on which to rest my artificial flowers, and thus, provide support which would enable me to extend the range of the flowers. I had asked my boss for a bundle of pea sticks, but he complained that as there were no peas in the ground as yet, there would be no pea sticks in the shops, Q.E.D. So, as I said, I kept my eyes open. I was debating whether or not to pick a few then and there and carry them back to my office in the dark, when suddenly a voice said, 'Hallo!' and I looked up about a foot and a half, and there was Tony Hutley, a policeman.

I said, 'Oh, Tony! How you did startle me – what are you doing, prowling around in mufti, it's not fair!' and Tony roared with laughter because I had jumped half a mile.

Just goes to show how careful one should be, when contemplating an illegal step, to have a solicitor handy in case you get caught! As it was, I went over again this morning with my eyelashes curled and asked the head gardener if I might have some twigs, a bundle of pea sticks, and if it was too much trouble for him I could ask one of my men to come over and pick them for me and get arrested for doing so. The head gardener chuckled and said 'Yes, that's about what usually happens. I'll have them sent across for you. Will this morning, a little later on, do?' So I thanked him profusely and went back and started sorting out my flowers. Two hours later, I had been away from my office for a few minutes, and when I opened the door to come back again, the floor was covered with enormous branches of flowering and berried shrubs! Pea sticks, I ask you! What I wanted was a lot of leafless twiggery, because it had to stand in big baskets fastened to the wall about ten foot above the floor. Certainly there is no water available. So now we have enormous bowls of greenery everywhere, and Mr Bond says we look like a dam' Palm Court. (That's what every second- rate little boarding house or hotel calls the place their clients sit in, usually entertained by a two-piece orchestra and the clatter of washing-up coming through the door from the kitchen premises.) So now I shall have to go foraging in the New Forest for my own pea sticks at the weekend, and Mr B. will just have to put up with us looking either like an institution or a Palm Court. His criticism that without the flowers on the walls we looked like the former, I took as a great compliment from him. It is only with such difficulty I can wring compliments out of my boss, so I hasten to report them when I do succeed in getting one.

Tony Hutley – we used to know him as a little boy, and he is an absolute darling of a young man – asked if we still had the Austin, and of course I said no, we had changed it. Tony looked a little odd, and said, 'Yes, I thought I saw your brother the other day driving a Jaguar.' I hastened to tell him that we weren't that mad, the Jaguar being Mrs Fagan's property. 'Well,' said Tony, 'I must say your brother looked the part.' Mac was very pleased when I recounted this, and made a mental note to continue wearing his white silk stock with the Royal Marine crest embroidered on it!

. . . Mother, bless her Jonah-like disposition, is saying each day as I get home and there are no letters for me from anybody, 'I expect Mr Bigelow's ill, dear,' which is nice of her. I prefer to believe you are just miserable and disinclined to write. Besides, you and I know – and Mother doesn't – that I told you not to write. And, as I told you at the time, I mean that. So don't you; just you stay snug and warm indoors until the better weather comes. Wish I could join you – today it is raining in buckets, and blowing a half-hurricane, with the result that the rain is being forced in all the windward windows and we are mopping up every hour on the hour, and the draughts are just whizzing around our necks.

All the moans and groans for this week . . .

Yours most sincerely,

Frances

Dear Mr Bigelow,

Although naturally I am intensely sorry that you are ill, in another way I can bring myself quite easily to envy you. All you have to do (it's enough, goodness knows!) is to lie quietly there and do what you are told, and hold fast to my promise that you'll feel much better in the spring – and that's all. You have your every want attended to when the nurses feel like doing it, and all your friends are flocking to see you, and none of them think 'Oh, he's got nothing to do all day, let him come and see me'; your room probably resembles Westminster Hall when the monthly exhibition of the Royal Horticultural Society is 'on', and that funny smell is probably the mixed outcome of daffodils, roses, violets, hyacinths, and nasty medicine.

All this attitude of mine is a part of my lifelong envy of very small babies lording it in perambulators. Or, as you so comically say, 'baby carriages'. Not entirely lifelong, for no doubt I disliked it intensely when I was stuck in one myself. But looking back at those innocent days, what a great pity it is that we cannot appreciate how coddled and 'babied' we are, when we are; for all too soon we have to start and fend for ourselves, even if it is only warding off the blows of our larger siblings, to prepare us for the battle of Wall Street, or fighting the kitchen stove or what-ever forms the major cause of warfare in our adult life . . .

Tonight (it's midday Thursday at the moment) is the crucial night, when I shall know whether or not Mr Peet has corrected the French in my essay on you. If he hasn't, I have arranged a sheet anchor. Last night after the Wednesday class I helped Mrs Noble on with her coat, and she protested, so I said blandly that I wished to ask a favour of her and was just softening her up. So she said what favour? and I told her about the uncorrected essay, and please, if Mr Peet hadn't done it tonight, could I bring it around to her house over the weekend and get her help because it just had to be sent off by Tuesday, and even then, would cost a mint of money in airmail postage because it had been held up so long. She was delighted, bless her. Asked if I could come either after 10.30 a.m., on Saturday, when she would have been out and done the shopping and done her washing at the launderette and be home again cooking the Sunday dinner 'which we always have on Saturday'. Or, as she goes to the Reference Library to check up on details of lessons for the following week, on Saturday afternoon, I could come at six o'clock in the evening, and although she couldn't ask me to have tea, she could ask me to have a drink. All this when I was the one asking the favour! Poor dear – she is a widow with two now-almost-grown-up children whom she keeps by teaching languages. It's pretty hard going to earn a living and run a home at the same time, and do the shopping and the washing, let along undertake to correct 2,000 French word essays that get suddenly thrust at one!

My brother is in the doghouse again. If you went through that box of letters from me, no doubt you could tell me how many times he's been there during the past twelve years, but I can save you a lot of bother by saying it is x to the nth degree and no strange abode for him. This time he's there because the arrangement was I had the car last weekend. Well, I went around to his home at six o'clock Saturday and he wanted it, so he had it and promised to drop it off chez-moi at nine in the morning, on his way to the golf. At 10.30 a.m. on Sunday morning Audrey 'phoned and said he'd gone to golf but not bothered to stop in, as he had used his car all the way. He would come in at one o'clock on his way home and I could have it then. At 1.30 he telephoned to say he'd played golf and now he was playing snooker and would I please telephone Audrey and say he'd be home at 2.40, after leaving the car with me at 2.30 if I wanted it. I said yes, I did want it. Well, Mr B. at 4.10 p.m. I caught a bus . . . . . . Of course, I could not then do all the visits I had intended doing between nine o'clock in the morning and six at night. So into the doghouse it is for Master Frank MacPherson, and as a result I am getting the evening use of the car this week whenever I want it and sometimes when I don't, and I am to be taken next Wednesday to see Frankie Vaughan at the theatre. I cannot bear Frankie Vaughan, but who am I to say no when invited out by a penitent brother?

Oh joy! Last night I had the car to go to French class, while Mac stayed at home with Mother after having had dinner with us. I am always late home from this class, which goes on until 9.30 p.m. anyway (the other stops dead on nine) and last night I ran three other students home, and waited while some baby-sitters got ready, and then took them on my way home. So it was ten before I reached R— Drive, and Mac had been pacing up and down the sitting room, coated and ready, for half an hour, and Mother was almost in hysterics, he had been so infuriating! He didn't dare say anything to me, after the Sunday business, so I felt very pleased this morning when Mother complained at her suffering through my tardiness, and feel I have had my revenge a little bit. It made me wonder what he would be like, had he to wait from 9 a.m. until 4.30 p.m. for the car one Sunday.

Well, Mr Peet turned up complete with corrected essay on one Commodore B. last night. Whether he just didn't have anything to say, or whether the shock of reading it rendered him speechless, I don't know; but he just marched up to my desk, gave me a meaningful look (but what meaning I could not interpret) and plumped the manuscript in front of me. So by Monday it will be typed out, put into the hard covers along with the others and some illustrations, and posted to Rosalind for a birthday present. And, of course, knowing my sort of luck, she will have flown east to see you and not be there on the date. Never mind, it will be something for her when she gets back again after seeing you on your feet again.

Today there is a little wind and the sun is blazing down. As a result of a storm yesterday, the sea is still a bit 'swelly' and the great rollers are coming in as though drawn with a ruler – there is a strong line of shadow down the trough all the way from the end of the pier to Bolson's Jetty, a couple of hundred yards to the east; then, after this great clean-cut shadow has rolled shorewards a little, the breeze gently takes the tip and breaks it into a lacy foam, and then the whole thing gives up and comes crashing down in blue-white surf. I could watch it all morning. And I hope that you are able to watch your own bit of ocean, or bay, from your window and smell the salt air as your waves come rolling in.

Oh, thank you Mr Bigelow for Reader's Digest. It came one day this week, and I was very pleased because at first, not being able to decipher the date stamp, I thought you must be better already to have posted it on the 16th January. But then I got out a magnifying glass, and found it was the 16th December, and it had just taken a very long time to come. Never mind, I am hoping for good news from Rosalind in a few days now.

In the meantime, I shan't tire you, nor whoever is having to read this to you (if somebody does have to) but will get it under way quickly, and write to you another, shorter letter on Monday to wish you well again. And you know that if wishes were magic potions, you'd be out of doors right now tinkering with the bird table or feeder, or just shooing away some marauding squirrels. But I do hope you are better. Please do be.

Yours most sincerely,

Frances

Dear, dear Mr Bigelow,

Today it is so warm somebody (and I could hazard a guess who it was, too) has turned off the central heating, at least in my office. And I don't need it, either; that's how warm it is.

No doubt it is warm in your room in Bellport, but possibly from central heating and not from sun, although I most sincerely hope that even if the snow is still thick on the ground, the sun is shining on it and making life a bit better looking for you all; especially for you. I am sure it looks better to you, with Rosalind round to protect you from the nurses and doctors, and I am certain that between the two of you, you will get them hang-tied, outslung and snaffled very smartly. If those expressions aren't quite correct, blame my upbringing – I was brought up on fairy stories and not on Westerns so I don't know the jargon.

At French class last night somebody read out a little essay on the art of writing letters, which gave rise to a fairly heated discussion on that art, mainly between the teacher and me. In English, naturally; I cannot yet be heated in French, and anyway, as I know from hard experience, when I speak in French only the teacher understands me and to have a private discussion in front of the whole class would have been rude. So we battled in English, and oh Mr Bigelow I felt very much in need of your support, that I did, because it would appear that I break every rule for letter-writing that has yet been invented. Or that Mr Peet feels should be obeyed. And naturally, being me and modest, I could not say that I write interesting and amusing letters, and I wanted somebody to come along and say it for me, to squash the creature for suggesting that my methods were all wrong. I think we were really arguing about the opposite sides of the same coin, but I claimed that it was the spirit that counted and not the elegance of style, or handwriting, nor the excellence of paper nor the highfalutin moral tone; it was the character and feelings of the writer which had to be put across, so that the person writing the letter came in through the letter box with his letter. And the teacher kept on that it was an insult to use a ballpoint with which to write a letter, and silly little man-made rules of that ilk. I daresay it's the nature of the beast – no schoolteacher can avoid having his eye so closely glued to the bark of the tree, looking for boll- weevils, that he cannot possibly see the copse, let alone the wood or the forest.

Anyway, we finished up probably not at all impressed by each other's argument, but it gave me to think, and it gave me a long paragraph for this letter, and encouraged the stubborn side of my character to try even harder to ensure that my personality came to you with this letter. Last time I sent you a letter I asked you to imagine it was a bunch of flowers, with sweet perfume to sooth your distress and bring you thoughts of spring. This time will you please try even harder, and imagine I am visiting you. And, being modest again, I am darn good at visiting the sick, I can assure you, so would you please oblige me by feeling much better when this is finished and I have gone away again?

When I come in through the door, that being my usual means of egress, I am not sure whether you will be surprised or not; whether you have imagined me as being tall or short. And being sort of in-between (five foot five) I daresay the clothes I am wearing at the time will largely influence you, for we all look different at times, and some-times I imagine myself short and stubby, and sometimes (not often, alas) tall and willowy. I think I shall be tall and willowy on your behalf, so here I am, wafting in through the door and giving you a No. 1 beam, and a nasty jolt as I sit down bang on your feet.

So there we are; you propped up on your pillows in your four-poster, looking very patriarchal and ducal (if that does not offend your republican sensibilities) and me, all over willowy-like and having a hard time of it, too, what with sciatica and that lot stiffening up the spine. You know what I look like; dark and a bit hollow-cheeked, and I know what you look like; especially now as I spent hours recently drawing your face this way and that, over and over again, as illustrations for the book of essays. So we need no introductions, and get right down to talking.

Which is going to be difficult, because apparently people find it hard to understand what I am saying. Perhaps just for the occasion I can put on an act, and become as Dame Edith Evans, audible globally, like Christmas bells. You don't mind if it's not really 'me'? Just that once. Normally I talk very, very fast, and my words get jumbled up as they come out; sometimes I change my mind about what I am going to say, with the words all in my mouth on the point of coming off my tongue, and then the resulting mix-up is really awesome and people think I'm speaking Swahili. I hope they do; I should hate them to think that was the way I speak our beautiful English. But today I am talking very slowly and graciously and every word is coming off like a pearl; at least until we get going in our talk, and then I shall forget and the pace will become hotter and hotter until you cry for mercy. So then we shall stop and have a cup of coffee, or one of your punches, perhaps – only four bottles of whisky in it for me, please; I have a weak head.

And after that pause for refreshments you will get out your snapshots to show me; the ones of your wonderful dog, and those of all his successors; those of Rosalind as a little girl sans front teeth but with such an engaging grin, as all children seem to have at that particular age. I am quite sure you will do this – show me your snapshots – because it is inevitable when I visit somebody who is ill. Even when, as did once happen, I have something wrong with an eye and arrive with a black patch over it and the other watering like an English summer, in sympathy, I never have got out of seeing the invalid's snapshots. They are so often of the 'this is one of me, only the sun got in the camera lens' type, but I shall expect better of yours, so if you move the camera about when taking photographs, you'd better tuck those results hurriedly under your pillow, so as not to disillusion me about your skill.

Then, having gone through those, I shall get up and prowl rudely about your room, looking at your pictures and antiques and the view out of the windows. Shall probably pause by the windows to report to you on what is going on outside, so perhaps you will send word out before I arrive to have the bay full of scootering sailors careering around so that I can find something to describe to you other than the gyrations of your birds just outside the glass.

And then, of course, your nurse or your housekeeper or even Rosalind (though I would have thought better of her) will come in and say I am not to tire you out and it's time for you to take your pills, or have a nap or something equally tedious, and they will sweep me out along with the tray of dirty cups or glasses and let you rest again and gather strength so that when my next visit comes along, through the letter box with a faint 'plop' on the mat, you will be waiting to open and read it for yourself out of sheer curiosity as to what on earth I shall manage to think about for my next Saturday Special.

And in the hope that you will now rest and do as I pray, I bid you a fond au revoir, dear Commodore, with all my wishes for your contentment.

Yours most sincerely,

Frances