St. James’s and Pall Mall

If you frequent gentlemen’s clubs in Canada, you might raise a few eyebrows. Not in London. Gentlemen’s clubs here are about table talks not table dances. They are grand sanctuaries from a bygone era full of leather-bound books and armchairs where well-heeled Victorians first invented the idea of social networking. For over 300 years, the historic neighbourhood of St. James’s has been home to many of these clubs and their colourful club characters — some gentlemen, some not — including a few with links to Canada.

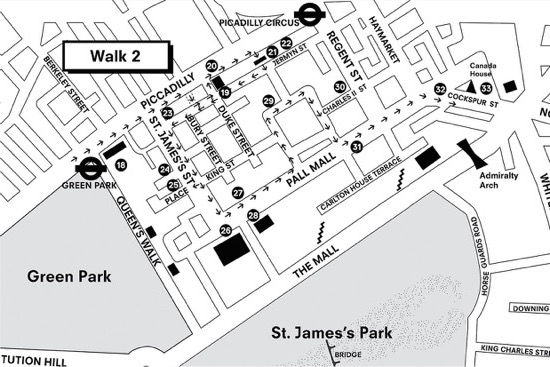

This walk starts at Green Park Tube station and ends at Trafalgar Square. The walking distance is about 1.2 miles (1.9 kilometres).

A Short History of the Area

St. James’s is a fashionable commercial quarter bordered by Piccadilly to the north, Haymarket Street to the east, and royal parks both south and west. Like the adjacent royal park, this area takes its name from St. James’s Palace, built for King Henry VIII (1491–1547; reigned from 1509) and official court of the monarchy since 1698.

Once royals settled in the area, ambitious courtiers soon followed. One of the first was Henry Jermyn (1604–1684), Earl of St. Albans, who saw promise in the vacant fields north of the palace. Jermyn was always looking for ways to advance himself, socially or financially. Like today, urban development was the way to accomplish both.

The centre of Jermyn’s new housing development was St. James’s Square, an elegant enclave designed for well-to-do courtiers keen to live near the palace. The gamble paid off handsomely for Jermyn and it wasn’t long before his square was the most desirable address in London and he a wealthy man.

In the 1700s, palace courtiers gave way to other members of society equally interested in advancement. These were wealthy landowners, military men, merchants, and politicians. This was the notorious age of gin, gossip, and gambling and the stakes were often very high: women lost their reputations from whispers and men their fortunes at cards.

Coffee was another vice of this immoral age. Its importation into Britain around this time started a craze that has never been kicked. Coffee stimulated creativity, commerce, and even dissent.[1] In time coffee houses evolved into private clubs. But many suspected the Ethiopian bean led to crime as well as revolution. Brazen highwaymen robbed coaches in Pall Mall and thieves snatched wigs and pickpocketed churchgoers in their pews. The area’s decline was so great that one aristocrat called it an “abyss of fog, sulphur, fever, cold and all the excretions on this side of the Styx.”[2]

Today, that fog has lifted and respectable St. James’s is home to fashionable retailers, auction houses, private capital firms, and others seeking the cachet of a smart London address. Private gentlemen’s clubs still dominate the area, though many have come and gone with time and taste. The Macaroni Club was one of these. It was formed in 1764 by foppish young men who had visited Italy, wore their hair long, and ate only pasta. But fashions and fads never last long, and neither did the Macaroni.[3]

The Walk

Leaving Green Park Tube station, let’s make our way east along the south side of Piccadilly past the gates to Green Park and the multitude of hawkers who gather here daily to sell double-decker bus tours. If you only have a few hours to see London, these popular tours are a great way to get your bearings; just don’t expect the guides to identify any sites of Canadian interest.

This America’s sweetheart business must stop. She’s my sweetheart. — Douglas Fairbanks to reporters, 1920[4]

The imposing Ritz Hotel is immediately on our right. A faded tribute to France’s belle époque, the hotel was built in 1905 by the Swiss hotelier César Ritz (1850–1918) using the latest construction techniques. Perhaps a greater innovation was Ritz’s insistence that all his rooms be equipped with private bathrooms — undoubtedly a big draw for the über-rich tired of passing each other in the hallways on their way to their baths.

One of many famous guests at the Ritz was Canadian-born Mary Pickford (1892–1979), a silent-film star, who honeymooned here in 1920. Pickford was the first actor to rise to global stardom because of movies. In fact, many say she created the age of celebrity that endures to this day.

The Ritz Hotel: The World’s First Movie Star

Gladys Louise Smith was living proof that that practice makes perfect. Hailing from a working-class Irish family in Toronto, she began her career at age seven performing in vaudeville for Canadian soldiers. From then on, she was constantly on the stage: first with a touring company in Buffalo and then in New York City where she adopted the name “Mary Pickford” and went on to star in the pioneering films of D.W. Griffith (1875–1948). By the time she was twenty-two, she had some twelve million fans worldwide who saw her films every day.[5]

In 1920, Pickford divorced her first husband and secretly married the American film idol Douglas Fairbanks (1883–1939). It was a match made in heaven, or at least Hollywood’s version of it. With her golden curls and feisty determination, Pickford was dubbed “America’s sweetheart” and Fairbanks the “All-American boy.” Word of the marriage of these two Hollywood royals made headlines around the world. But it wasn’t until the newlyweds arrived in London that they realized just how famous they were. The New York Times called their honeymoon “the most conspicuous in the history of the marriage institution.”[6]

In 1920 thousands of fans blocked Piccadilly to see the famous newlyweds Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks at the Ritz Hotel.

At the Ritz Hotel where the couple stayed, the scene was pandemonium. “Outside our window we saw them, thousands and thousands of them, waiting day and night on the streets below, for a glimpse of us,” recalled Pickford later. Her British fans snarled traffic so badly on Piccadilly that even King George V (1865–1936; reigned from 1910) got stranded in his limousine.[7]

Pickford’s fame was truly global. That’s because silent films were cheap to produce, easy to distribute, and understandable in any language. But if filmgoers made her a huge star almost overnight, they unmade her just as quickly too. In a few years her stardom faded, replaced by more sexually charged screen idols. In the 1930s, Pickford retired from show business, divorced Fairbanks, and withdrew into seclusion. For the most part, the world’s first global movie star lived the rest of her life in obscurity.

At the corner of St. James’s Street, cross over and continue northeast along Piccadilly for about 100 metres (328 feet). Descend into fashionable Jermyn Street through the ornate Piccadilly Arcade.

Jermyn Street is London’s best-known shopping area for high-end clothing, second only in reputation to Savile Row’s suit-makers. At the foot of Piccadilly Arcade, a statue of the Regency dandy George “Beau” Brummell (1778–1840) greets us. The inscription reads: “To be truly elegant one should not be noticed.” Brummell was a London bon vivant who spent so much on clothes and gambling that he died badly in debt. It’s a warning to the wise that nothing comes cheap on Jermyn Street.

Trivia: Mary Pickford lived at 211 University Avenue, Toronto. The site is now the city’s Hospital for Sick Children. A plaque unveiled in 1973 honours the former home of the world’s first movie star.

Another bon vivant of Jermyn Street, though not as well-known, was General John “Jack” Hill (ca.1680–1735). He was a fun-loving army officer who was well connected at court. When he took part in a disastrous bid to capture Quebec forty-eight years before the more famous Major-General James Wolfe (1727–59), those connections came in very handy.

Jermyn Street: General Hill’s Misadventure

In 1711, Europe’s two squabbling sisters — Britain and France — were once again at war. This was the War of the Spanish Succession or Queen Anne’s War as it is sometimes called. Urged on by American colonists, the British government decided to strike against France by capturing its fortress stronghold at Quebec. But the expedition would be perilous and costly, and needed the blessing of none other than Queen Anne (1665–1714; reigned from 1702) herself. To win her over, the government proposed Hill to command the army.

Like many military men of the period, Hill owed his success more to his connections than his capacities. One of his early patrons was the influential Sarah Churchill (1660–1744), 1st Duchess of Marlborough. When her influence faded at court, Hill plucked another ace from his fashionable sleeve: his own sister Abigail. She became the queen’s intimate confidant. Under Abigail’s persuasion, Anne agreed to the dangerous plan. Along with Hill would go the scarcely more talented Admiral Sir Hovenden Walker (ca.1656–1728) in charge of the navy. The two set off to Canada with high hopes and 5,000 of Britain’s best fighting men — but the attack was an unmitigated failure.

Strong winds, dense fog, and a weak knowledge of the St. Lawrence River made havoc of the expedition. Eight ships foundered on a rocky shoal called Egg Island 500 kilometres (310 miles) from Quebec City and some 900 men drowned. Hill and Walker abandoned their mission and beat a hasty retreat home to face a cool reception. “Was it expected that I should have commanded wind and weather?” Walker demanded.[8] He fought accusations of cowardice but not so much the well-connected Hill. Promoted to major-general, he continued his drinking and good living in Jermyn Street until it was too much for him, and died a worn-out bachelor here in 1735.

Continuing east on the north side of Jermyn Street to Duke Street, we come to the landmark retail store Fortnum & Mason (181 Piccadilly).

Fortnum & Mason should not be kicked around as a public football. As long as I live, these shares will never leave my hands. — Garfield Weston, May 1951

Renowned for its window displays and enticing jams, jellies, and teas, this venerable old store dates to around 1707 when William Fortnum, a footman to Queen Anne, began selling groceries to St. James’s rich. Fortnum got his start by melting down the discarded ends of palace candles and making new ones with his sidekick Hugh Mason. The Art Nouveau light sconces on Piccadilly may look like something out of Walt Disney’s Beauty and the Beast but no doubt pay tribute to Fortnum’s entrepreneurial spirit as lamplighter to the queen. Turn left and walk up Duke Street to Piccadilly. If you go in by the side entrance, you’ll avoid the crowds but miss more of the wonderful display windows on Piccadilly.

Despite its Englishness inside and out, Fortnum & Mason is the crown jewel of a British food empire with Canadian roots. In 1951, the financially troubled store was purchased by the Canadian billionaire W. Garfield Weston (1898–1978). Weston was a canny businessman who had created a huge multinational food and retail company from his father’s small bakery business in Toronto. He owed his success to adopting modern bread-making techniques and knowing what his customers liked. When a journalist once marvelled how his machinery blew excess icing off the biscuits, Weston replied: “Oh no, it’s blowing the profit on.” His father, George, was even cannier. “People will eat horse shit if it has enough icing on it,” he once remarked.[9]

It was the billionaire Weston who installed the four-ton clock above the main entrance of the store. On the hour, the store’s namesakes, Messrs. Fortnum and Mason, appear from behind bronze doors and bow to each other in a hokey but charming glockenspiel. If you arrive at the right moment, cross Piccadilly to see the show.

In 1971, a meeting took place here between the billionaire Garfield and his son Galen (b. 1940) that changed Canadian eating habits forever. It also solidified a food-and-fashion dynasty in Canada that endures to this day.

Fortnum & Mason: The Royals of Retail

Like the fall of the Roman Empire, the cracks of Garfield Weston’s food empire started in the provinces. In the late 1960s, Weston-owned Loblaw grocery stores in Canada were losing truckloads of money. For the aging bread man, the barbarians were at the gate. In 1971 he called his son Galen into his office at Fortnum & Mason to decide the fate of the Canadian enterprise. He gave his son a year to turn Loblaw around or close it down.

Galen wasn’t exactly the ideal grocer’s son. A tall, handsome, and outgoing socialite with a penchant for polo, his only connection to the Canadian food chain was stocking shelves there during his summer holidays. But he had learned a few tricks at his father’s knee and took over as CEO, moving to Canada with his Irish model wife, Hilary Frayne (b. 1942). It would certainly prove a safer place than Ireland: the Provisional Irish Republican Army had once tried to kidnap Galen to ransom him for cash.

Weston decided to take the Canadian food chain upmarket and hired an old university roommate Dave Nichol (b. 1940), as the company’s president. Like Banting and Best, it was a fruitful collaboration. They revamped stores, adopted a new red-and-orange logo, and introduced fancy products under the President’s Choice label. If Garfield the father brought sliced bread to Britain, observers say Galen the son brought balsamic vinegar to Canada.

Today, Canada’s royal family of retail owns Loblaw, Real Canadian Superstores, Holt Renfrew, and T&T, the largest Asian grocery chain in the country. And the dynasty seems to be going strong with the fourth generation. Galen Jr. (b. 1972) is Loblaw’s current president, as well as geeky TV spokesperson.

After stocking up at Fortnum’s, continue along Piccadilly past Hatchard’s, London’s oldest booksellers (187 Piccadilly). Set back from the street a little farther on is St. James’s Piccadilly church.

St. James’s Piccadilly, dating to 1676, is the oldest building in the area. It was financed by Henry Jermyn himself and designed by the architect Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723). Some say its modest scale allowed churchgoers to hear not only the sermons in the pulpit but the gossip in the pews.[10] Although badly damaged during the Second World War, the church was restored with its original woodwork by master carver Grinling Gibbons (1648–1721).

Trivia: In 2004, Galen Weston Jr. and his sister, Alannah, opened a club of their own in Toronto: the Spoke Club targeted trendy, creative types.

Adjoining the parish is a peaceful former churchyard whose gravestones have been lost to time and the need for patio stones — like the ones you’re probably standing on. Nowadays, a social worker in a green trailer offers drop-in counselling to London’s homeless. A few of these find refuge inside, so be prepared.

Inside St. James’s Piccadilly four large windows on both sides make it surprisingly bright. Under the second window along the Piccadilly side is a memorial to Loyalist Guy Johns(t)on (ca.1740–88) of Guy Park, New York. He was a bombastic Irishman who was forced to abandon his home and flee to Canada during the American Revolution. For this and much more, he vowed revenge against the United States.

Johnson Memorial: A Loyalist’s Curse

In 1755, Guy Johnson arrived in pre-Revolutionary Boston without a shilling in his pocket but a good family connection to bank on: his relative, the prosperous and well-known Sir William Johnson (1715–74), superintendant of the Mohawk Indians in upper New York province. Before Bostonians could say “Bill’s your uncle,” the spendthrift Johnson was so badly in debt that Sir William had to rescue him with a chequebook. It didn’t seem to bother the older Johnson: Guy married one of Sir William’s daughters in 1763 and became his trusted aide, even taking over Sir William’s Indian duties after his death.

Johnson’s gift for words and Irish bravado made him genuinely popular with the Mohawks, who named him Uraghquadirha or “Rays of the Sun Enlightening the Earth.”[11] As the American Revolution gathered steam, Johnson worked hard to keep the Mohawks loyal to Britain but was forced to flee to Montreal with his family when fighting broke out near his Mohawk Valley home in 1775. Further tragedy struck nearly within sight of Canada when Johnson’s exhausted wife died at Oswego, New York.

Distraught, Johnson vowed revenge against the American patriots who had caused him so much grief. With the help of the Iroquois leader Joseph Brant (ca.1743–1807), he was put in charge of Canada’s Indians and eventually made good his curse by leading devastating raids on the American frontier from Fort Niagara. In 1783, he returned to London to seek restitution for lost property in New York but died here uncompensated and unvalued, “broken in health, spirit and estate.”[12]

By the third window along the same side is a memorial to Sir Colin Campbell (1776–1847), a one-time lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia. A Scot from a military family, Campbell served under the Duke of Wellington and admired his commander so much he named his son after him. Although Campbell was offered the governorship of Tobago as a reward for military service, he passed up the tropical paradise for “the beautiful and interesting” Nova Scotia. His term from 1834–40 in the feisty colony, however, would prove anything but idyllic.

Campbell Memorial: Against the Tide in Nova Scotia

When Sir Colin Campbell landed in Nova Scotia as the province’s new governor in July 1834, he knew how to win over a crowd: hosting picnics and parties and bravely visiting areas hit by cholera. But it didn’t take long before the conservative Scot started to ruffle a few feathers, especially with the province’s elected assemblymen who wanted a greater say in how Nova Scotia was governed. Unfortunately for a man like Campbell, the assembly’s grievances were beyond his comprehension. He didn’t know it yet but he was battling a tide as strong as the Bay of Fundy’s. It was called democracy, or the reform movement.

One of Campbell’s political rivals was the fiery Joseph Howe (1804–73), a newspaperman and leading Reform politician who later opposed Confederation. Howe and his supporters disliked Campbell so much they lobbied London for his dismissal. Mind you, not every Nova Scotian shared their view. Perhaps fearing the end to his picnics and parties, many Nova Scotians petitioned for Campbell to stay.

The matter came to a head when Canada’s governor general, Sir Charles Poulett Thomson (1799–1841), arrived in Halifax to settle the stalemate. Thomson, a Reformer himself from the British Whig party, took the side of Howe and the assembly against Campbell. “The time has gone by when these North American provinces can be governed in the old system,” he said.[13] Sir Colin was sent packing to Sri Lanka and returned to London in 1847, old and feeble-minded.[14]

Just beyond the fourth window is another plaque. It is a memorial to a physician named Sir Richard Croft. If it weren’t for Croft, Queen Victoria might not have been Canada’s first queen. Croft was a royal obstetrician to Princess Charlotte, the only child of King George IV (1762–1830; regent from 1811–1820; reigned from 1820). When Charlotte gave birth in 1817, Croft botched his bedside care so badly that both mother and child died. Without an heir, the crown passed to the king’s niece, the young princess Victoria.

Exit the church on Jermyn Street and partake in some retail therapy or head back along Jermyn Street in the direction from which we came: St. James’s Street.

I dined alone at the St. James’s Club among diplomats and old prints — rather dreary. — Canadian diplomat Charles Ritchie, 1942[15]

We now find ourselves on St. James’s Street in the heart of London’s clubland. This elegant but busy street and its sibling Pall Mall are the principal addresses of many of London’s best-known gentlemen’s clubs. At one time there were more than 200 such establishments in London. Today fewer than a quarter of them survive.

The area’s oldest and most preeminent is White’s Club (37–38 St. James’s Street), just up a little toward Piccadilly. Its origins go back to White’s Chocolate House, founded in 1693, though the present clubhouse dates from about 1787.

If you look behind the iron railing of White’s, you will see an odd set of steps that don’t lead anywhere. That’s because the club’s door was moved right in 1811, perhaps in keeping with the club’s politics.[16] The central bay window was an ideal spot where Brummell, our dandy of Jermyn Street, could play cards and keep his eye on the fashions of unsuspecting passersby.

Trivia: In 1949, Governor General Harold Alexander signed the bill that finalized the union between Newfoundland and Canada.

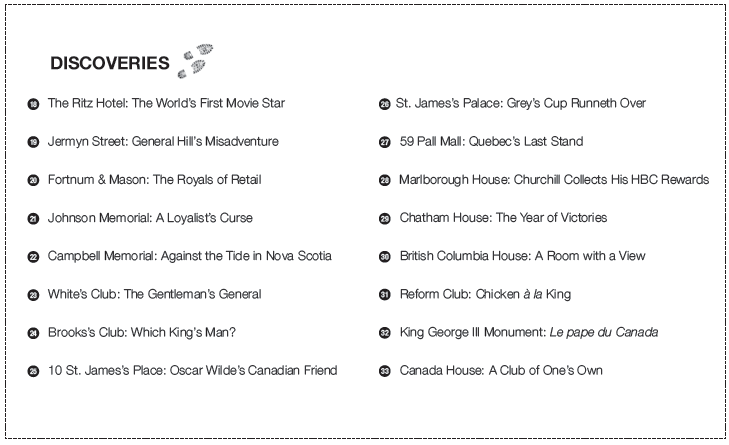

Among the portraits on the walls of White’s is one of distinguished club member Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander (1891–1969), 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis. It’s by the English portrait painter Sir Oswald Birley. Alexander was a decorated war hero and the last of a vanishing breed: the gentleman soldier. He was also Canada’s last British governor general from 1946–52.

White’s Club: The Gentleman’s General

Harold Alexander was a handsome, fastidious soldier whose shoes and manners bore equal polish. Born into an Anglo-Irish aristocratic family, he always dreamed of being a painter. But like many of his generation, those dreams were upended when he enlisted in the First World War. By 1937, he had climbed in the ranks to become the youngest general in the British Army, known to everyone simply as “Alex.”

Even in the face of adversity, Alex was always a gentleman. Confronted by the German blitzkrieg (lightening war) in the Second World War, he was ordered to evacuate his army from France. Although British prime minister Winston Churchill (1874–1965) had given him permission to surrender, he defended the evacuation at Dunkirk to the last man. “Is anyone there?” he called out along the beaches in English and French before getting into a boat and leaving himself.[17] Although he later won battles in North Africa, the Middle East, and Italy — often at the head of Canadian troops — some say he might have been a greater commander if he had not been so nice a man, and so deeply a gentleman.[18]

When peace came, Canada asked if Alex would be the country’s next governor general. He had expected another job in the army but Churchill told him Canada was a much more important post.[19]

As governor general, Alexander proved as popular with Canadian civilians as he had been with his troops. But he also found the time at last to pursue his long-delayed passion to paint. He studied art, befriended Canadian artists, and took along his easel just about everywhere he went around Canada. Such was his fondness for the country that he added Baron Rideau of Ottawa to his title when he was granted an earldom in 1952.

Not every club member could claim to be as much a gentleman as Alexander. Drinkers and gamblers were legion at White’s. Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), the satirist and author of Gulliver’s Travels, was certainly no fan. He shook his fist every time he walked by the place and called it “the common rendezvous of infamous sharpers [swindlers] and noble cullies [pals].”[20]

The statue of Earl Alexander of Tunis, Canada’s last British governor general, in the Wellington Barracks on the west side of St. James’s Park. It was erected in 1985.

Unhappy shareholders of Hollinger International might do the same. That’s because Conrad Black (b. 1944), Baron Black of Crossharbour, was a member here. He joined with the help of Peter Carington (b. 1919), 6th Baron Carrington, a former Conservative foreign secretary. Black offered Carington a lucrative directorship on the board of the Daily Telegraph and like magic Black was tucking into his sherry trifle at the members’ table. “He is a very generous man,” Carington said sheepishly of his new patron and fellow club member.[21]

Let’s leave White’s now and walk farther down St. James’s Street.

The 1960s office tower in the plaza behind Boodles club (28 St. James’s Street), is the headquarters of the weekly news magazine The Economist. It was created in the turbulent 1800s to advocate for free trade and put an end to the imperial trading system that gave preference to imports from colonies like Canada.

Despite its serious name, the magazine has a whimsical streak. In 2003, The Economist put a moose sporting sunglasses on its cover and called Canada cool for its economic success and boldness in social matters like the legalization of gay marriage and possible decriminalization of marijuana. This was under Prime Minister Jean Chrétien (b. 1934). A year and a half later, the magazine changed its tune and called Chrétien’s successor, Paul Martin Jr. (b. 1938), “Mr. Dithers.” The name persisted even if Mr. Dithers didn’t.

Across the street opposite is another gentlemen’s club: Brooks’s (60 St. James’s Street). It was founded in 1764 for members of the more liberal Whig Party. A wit once compared it to a duke’s country house — with the duke lying dead upstairs.[22]

Whigs sympathized with the patriots in the American Revolution and the lead plant containers outside the door recall the date 1776. One of the club’s prized possessions is said to be a book that lists the wagers of early members. One entry for £50 was placed in 1777 by club member General John Burgoyne (1722–92) or “Gentleman Johnny” to his friends. Burgoyne wagered he would defeat the Americans by attacking with an army from Montreal and be back at the club in time for Christmas. Alas, the boastful Burgoyne wasn’t cut out for backwoods warfare. His Canadian attack failed and he lost his army as well as his shirt.[23]

Trivia: Vincent Massey gave his collection of modern British art to the National Gallery of Canada. Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King was unimpressed. “You cannot possibly like those dreadful pictures Vincent and Alice buy,” he said.[24]

Canada’s Vincent Massey (1887–1967) was a member here. Massey succeeded Alexander as governor general of Canada and was the first Canadian to hold the vice-regal post. But not everyone noticed the difference. Massey was such an imperialist some people didn’t think he was quite Canadian enough.

Brooks’s Club: Which King’s Man?

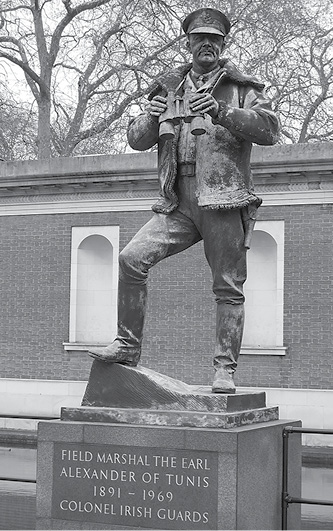

Vincent Massey was a small, cultivated lawyer from an Ontario family made rich from selling farm tractors across the British Empire. After helping secure a Liberal victory in 1935, he was appointed as Canada’s high commissioner in London by a grateful Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King (1874–1950). King would soon regret his decision.

For Massey, the London job was a dream come true. Educated at Oxford University, he adored everything British: their manners, tastes, and traditions. He knew every duke by name, one diplomat observed, and was friendly with all the royals — dubbed a real king’s man. For some, his British reverence and clubbable, upper-class manner was just a little un-Canadian. One governor general thought him a bit “too Balliol” (after his Oxford college) while the Canadian journalist Charles Lynch joked he made English toffs (aristocrats) feel inferior.[25]

It may have been the reason King kept his old Liberal friend on a short leash in London. King was as much an anglophobe as Massey was an anglophile. King knew Brits, he once warned his high commissioner, and they needed to be watched.[26] Inevitably, the high costs of living in London also strained their transatlantic relationship. King refused to buy an official residence for Massey in London or even to bombproof Canada House on Trafalgar Square during the Second World War. As a result Massey had to live in rented digs and authorized the embassy’s improvements himself.[27]

Their relationship was never more tested than when King visited London in 1946. Inside Canada House, the prime minister found photographs of the king and queen prominently on display but his own hidden behind a door. He never forgave Massey for the sleight.[28]

Opposite King Street is St. James’s Place on our right. Number 10 was once a small hotel. Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) lived here in 1893–94 at the height of his success. Much of his An Ideal Husband was penned here.

A flamboyant fin-de-siècle writer and advocate of the decorative arts, Wilde was celebrated and loathed in equal measure. He lived a self-fulfilling prophecy to be famous and, if not famous, notorious. In reality, he was both.

Canadian prime minister W.L. Mackenzie King is greeted in London by his anglophile high commissioner, Vincent Massey.

Wilde chose this tucked-away hotel in St. James’s Place to elude the prying eyes of society while he wrote, sipped German white wine (hock) and soda, and conducted his discreet — and at the time criminal — relations with other men. Without any luck. In 1895, he was arrested at the Cadogan Hotel (75 Sloane Street) in London’s Knightsbridge area and put on trial. An eyewitness testified Wilde often entertained young men of “quite inferior station” here in St. James’s Place. This testimony helped seal Wilde’s fate and send him to prison to do hard labour.[29]

Trivia: In 1887, Oscar Wilde is said to have sat for a portrait by the Canadian painter Frances Richards. “What a tragic thing it is,” Wilde mused. “This portrait will never grow older but I shall.” His novella soon followed, called The Picture of Dorian Gray.[30]

As our walks don’t take us into Knightsbridge, we’ll use this spot to recall Wilde’s relationship with Canada’s Robert Baldwin Ross (1869–1918), a lover and lifelong friend of Wilde’s who was with the writer at the time of his arrest. John Betjeman (1906–84), a British poet laureate, later imagined the moment in his poem “The Arrest of Oscar Wilde at the Cadogan Hotel”:

More hock Robbie — where is the seltzer?

Dear boy, pull again at the bell!

They are all little better than cretins,

Though this is the Cadogan Hotel.

10 St. James’s Place: Oscar Wilde’s Canadian Friend

Robert Baldwin Ross was the youngest son of John Ross (1818–71), a well-respected attorney general in Upper Canada, and Elizabeth Baldwin, daughter of the Canadian Reformer Robert Baldwin (1804–58). When the elder Ross died after an illness in Toronto, the family moved to London. Despite spending only a few years in Canada, the youngest Ross never lost his Canadian heritage or his accent.[31]

Short with boyish features, “little Robbie” was not particularly handsome but there was something about his mischievous face that endeared him to Wilde. How they met is not known for certain but it may have been through a Canadian painter and neighbour in Chelsea named Frances Richards (1852–1934). In any case, when Ross was a student at Cambridge University, the two were possibly lovers.

Ross’s unashamed homosexuality and aesthetic lifestyle (like Wilde, he wore his hair long) made him unpopular at the university, where he was bullied and dumped in a college fountain. As a writer later in Edinburgh and London, he remained a devoted friend to Wilde. When others deserted the playwright at his trial, Ross stood by him, even dangerously doffing his hat to the humiliated playwright in public.

On the day of Wilde’s arrest, Ross urged the distraught playwright to flee to France for safety. Wilde didn’t heed his advice. “The train is gone, it’s too late,” he said in defeat. After Wilde’s imprisonment and death, Ross managed Wilde’s estate and erected a headstone at the writer’s grave in a Paris cemetery. In due course, he even joined Wilde there.[32]

At the foot of our street is St. James’s Palace. Dwarfed by grander buildings, its Tudor scale can be a bit underwhelming. While it is still the official seat of the monarchy (known as “the Court of St. James’s”), in practice all sovereigns since Queen Victoria (1819–1901; reigned from 1837) have lived in the more impressive digs around the corner. Little of the original Tudor palace survives except for the entrance, some reception rooms, and the Chapel Royal within. Today, it is mostly used for offices and charitable functions.

Controversy dogged Robbie Ross all his life. He once joked that his own epitaph should be: “Here lies one whose name was writ in hot water.”[33]

Many royals are associated with St. James’s Palace. Queen Mary (1516–58; reigned from 1553), who was elder half-sister to Queen Elizabeth I and better known to us as “Bloody Mary,” died here in 1558 and King Charles I (1600–49; reigned from 1625) spent his last few hours in the chapel praying before walking to his execution in nearby Whitehall. Other monarchs were born here including King Charles II (1630–85; reigned from 1660), his brother King James II (1633–1701; reigned 1685–88) as well as Queen Anne.

Across from Friary Court on Marlborough Road is the Queen’s Chapel, built in 1623 by the architect Inigo Jones (1573–1652). It is used as a Chapel Royal or special church of the monarch. Two such Chapel Royals are found in Ontario: the Queen’s Chapel of the Mohawks in Brantford and Christ Church, Chapel Royal of the Mohawks in Deseronto. They honour the special links between the sovereign and the Mohawk people who remained loyal to Britain during the American Revolution.

St. James’s Palace was also the birthplace of Sir Albert Grey (1851–1917), 4th Earl Grey, governor general of Canada from 1904 to 1911. Grey was raised at the palace and came from a prominent political family (his grandfather was the prime minister who inspired the name of tea made with Bergamot). He wasn’t a royal, just the son of parents who worked for them.

If Canadians recall Grey at all, it is for the trophy in Canadian football that bears his name. While his cup fostered Canadian nationalism in sport, however, it had the unintended effect of dividing Canada from the empire Grey loved.

St. James’s Palace: Grey’s Cup Runneth Over

Albert Grey was a crusader who believed almost religiously in the British Empire. While others gave their lives for the cause, he gave his hair: in India he suffered severe sun stroke and was left bald for the rest of his life.[34] As Canada’s governor general, he was a fervent promoter of imperial schemes — many of them crazy — which often put him at odds with just about everyone including prime ministers Sir Wilfrid Laurier (1841–1919) and Sir Robert Borden (1854–1937).

“I doubt Albert’s level-headedness,” the outgoing governor general confided to his wife on learning of Grey’s appointment, “and an enormous amount of harm may be done here by any impetuous action and want of judgment.” History would prove these words prophetic in an odd way. It centred on a $48 trophy.

In 1823, William Ellis invented a game in Rugby, England, by picking up a soccer ball and running down the field with it. (His tombstone says he had a fine disregard for the rules.) “Rugby” quickly spread with immigration to Australia and New Zealand and along with cricket became the main sport of the British Empire. Canada embraced the game too and introduced it to the United States in 1874. Not long afterward the Americans changed the rules again, eliminating the scrum for a ball passed to a quarterback, and football was born.

In 1909, when Grey donated his cup for amateur rugby football in Canada, the game was a bit of an odd hybrid: neither rugby nor modern Canadian football. But Grey’s cup accelerated the game’s unique evolution. As more and more amateur clubs across Canada vied for his trophy, it spurred the creation of a common rulebook. Before long rules on forward passes, snap backs, interference, and even how many Americans could play on a team created a new game that drove a sporting wedge between the empire with its fondness for Ellis’s rugby and Canada with a national game of its own.[35]

Now let’s leave one game for another as we look down one of London’s most fabled streets: Pall Mall. The name comes from a medieval Italian game palla a maglio (ball to mallet), which King Charles II loved to play here in an alley bordered by elms.

Walking through St. James’s Park I encountered that gypsy woman whom I have seen telling people’s fortunes. I decided to try mine. She took my hand, looked at it, and instantly said: “They will never make a gentleman of you.” —Canadian diplomat Charles Ritchie, April 1969[36]

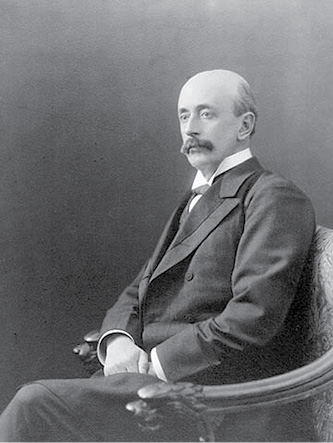

Lord Grey, governor general of Canada from 1904 to 1911. His trophy for football divided Canada from the British Empire — in sport at least.

Opposite us on Pall Mall is the Parisian-style office of the Quebec Government (59 Pall Mall). At one time many provinces had buildings in London to promote trade but now only Quebec House remains.

In 1981, an angry Quebec Government made a last-ditch effort to stop the patriation of Canada’s constitution from Britain. If old soldiers never die, then the ghost of René Lévesque (1922–87) may still haunt this place.

59 Pall Mall: Quebec’s Last Stand

When René Lévesque failed to win special recognition for his province during constitutional negotiations in the early 1980s, Quebec’s chain-smoking premier set his sights on London. His front gunner in the British dogfight was his government’s agent-general in London Gilles Loiselle (b. 1929). He was told to do everything in his power to stall the vote in Britain’s parliament that would allow the constitution to be sent home to Canada.

The battle brought lobbyists from all sides of the issue to London to stuff hungry parliamentarians with food and propaganda.[37] Loiselle was a tough man to beat. A former journalist with Radio-Canada and federal cabinet minister, he knew his pinots from his clarets and spoke equally well the queen’s English and the French of Molière. He was the kind of Péquiste, someone said, who liked to taunt Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (1919–2000) with being an English snob, but was no stranger to pretentiousness himself.[38]

Loiselle knew the best way to a politician’s heart was through his stomach. He also knew that the real power in Britain’s parliament rested with its backbench MPs. With one of the best chefs in town, a wine cellar, and a hefty hospitality budget, Loiselle wined and dined some 250 parliamentarians to explain Quebec’s grudges with Trudeau and his government. “I have never seen the booze flow with such abandon,” a columnist observed in the Sunday Times.

As pleasurable and intoxicating as it must have been, Loiselle’s “lobbying à la carte” ultimately failed. Much to Lévesque’s horror, Britain passed the Canada Act with little objection in early 1982, severing Canada’s last legal ties to Britain and paving the way for the creation of the country’s new constitution, which didn’t include Quebec.

Embittered and betrayed, Lévesque famously muttered: “Trudeau m’a fourré” (Trudeau fucked me). He was to die from heart failure a few years later.[39]

Before we leave Quebec House, note the marks on the façade on either side of the blue fleur-de-lys. At one time, two poles jutted out over the sidewalk for the flags of Canada and Quebec. In 1995, the Quebec Government quietly removed the Canadian flag in a public assertion of its independence abroad.

Tucked out of sight across the street is Marlborough House. Having discovered some of its occupants on Walk 1, we’ll now say a word or two about the owners for whom the house was originally built: John and Sarah Churchill, 1st Duke and Duchess of Marlborough.

Lévesque’s agent-general in London is losing no time in popularizing his provincial government. On Saturday night, he had all the chauffeurs in for a drink. —Canadian High Commissioner Paul Martin Sr., November 1977[40]

Britain’s original power couple, the Marlboroughs were distant ancestors of Winston Churchill and leapt to fame and influence during the reign of Queen Anne. Marlborough’s victory over the French at the Battle of Blenheim (1704) in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) made him a national hero and very, very rich.

Pluck up the courage and poke your head through the gateway. Sir Christopher Wren designed the original redbrick house especially for the duchess. She disliked the ornamentation of Blenheim Palace, her other home near Oxford, and wanted something “small, plain and convenient” in the heart of London. Despite their tremendous wealth, the Marlboroughs were fanatically frugal; after landing his troops in Holland, the duke loaded up his navy ships with bricks to take advantage of the free transportation home. When it came to his job as a governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, he similarly profited from his military connections.

Trivia: Lord Palmerston, Britain’s foreign minister, once said the role of the Hudson’s Bay Company was to strip Canadian quadrupeds of their furs and keep Canadian bipeds off their liquor.

Marlborough House: Churchill Collects His HBC Rewards

Granted a royal charter in 1670, the Hudson’s Bay Company is one of the oldest incorporated merchandising companies in the world. But in the first fifteen years of operation, it failed to make a penny for its owners.

In 1685, before he became Duke of Marlborough, John Churchill agreed to become the third governor of the HBC. At thirty-five, he was handsome and courteous, a rising military star, and very well connected in Parliament and at court. It was for these reasons that the company sought him out for the governorship. The company’s second governor and Churchill’s immediate predecessor had been utterly incompetent: a neglectful and ineffective man who even refused to sign everyday business papers. He would prove an even less successful king.[41]

Churchill, to the contrary, was a man of action. Using his control over Britain’s military, he directed the navy to help protect supply ships from French raiders sailing in and out of the trading posts in Hudson Bay. He also ensured the company’s monopoly to trade furs was formalized with an Act of Parliament. As a result of these and other efforts, the HBC finally became profitable under Churchill’s watch and paid generous dividends — the company’s first.

Such was the company’s gratitude that it named the Churchill River after him in what later became Manitoba.[42]

Walk along Pall Mall to St. James’s Square. Across from the entrance to this square once stood the Conservative Carlton Club.[43] In October 1922, Andrew Bonar Law (1858–1923), a New Brunswicker by birth, was returned as leader of the Conservative Party by backbench MPs here. Shortly afterward, his party won a general election — making him the only British prime minister born outside the United Kingdom. Tory backbenchers to this day are known as the 1922 Committee in reference to these historic events it is said.

Now let’s head north into St. James’s Square. At one time the most fashionable quarter in London, nowadays it’s hard to imagine it as a refined residential square.

Working our way around to the top, we pass the East India Club and private London Library to come to 10 St. James Square. This was the home at various times of three British leaders: William Pitt (1708–78), 1st Earl of Chatham, Edward Smith-Stanley (1799–1869), 14th Earl of Derby, and William Gladstone (1809–98). For now, we’ll just consider the first of these.

Chatham House: The Year of Victories

William Pitt ranks as one of Britain’s greatest leaders. At the height of the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), he became secretary of state and leased 10 St. James’s Square. From there he directed a series of bold military manoeuvres in North America that would change the continent forever.

Pitt was a political outsider known as the Great Commoner. Energetic, brilliant, and a champion of trade, he was also highly unstable: at times so melancholic he couldn’t bear to see anyone. He was also relatively poor and is said to have kept his rooms so cold that the visiting prime minister, the Duke of Newcastle, once had to climb into a bed just to stay warm.

Pitt’s plan to win the war called for a series of surprise attacks on French fortresses overseas at Louisbourg, Quebec, and elsewhere to reduce the power of France. One by one, these strongholds fell and 1759 became known the Annus Mirabilis (“Year of Victories” in Latin). When Fort Duquesne on the Ohio River was taken, British soldiers honoured their leader by renaming it Pittsburgh.

The other part of Pitt’s winning strategy was to put his trust in bold, young military men like Major-General James Wolfe. Wolfe is said to have dined with Pitt here on the eve of his departure for Quebec. After dinner Wolfe stood up, flourished his sword, and struck the table with it in a show of bravado. Pitt may have wondered about Wolfe’s sanity but no doubt saw the fearless qualities he was looking for in a military leader. He may also have recognized Wolfe was dying of tuberculosis and had nothing to lose from the venture. “Good God,” Pitt said afterward, “that I should have entrusted the fate of our country to such hands.”[44]

Today, Britain’s Royal Institute of International Affairs occupies the building, now known as Chatham House, after the earldom bestowed on Pitt. The term “Chatham House Rule” was coined here in 1927 and simply means discussions are “not for attribution.” While the term is often pluralized, Chatham House’s web site reminds us that there is — and has only ever been — one rule.

Continue around the square. To our right at the top of Duke of York Street is the parish church of St. James’s Piccadilly we visited earlier. The bronze equestrian statue in the central square portrays King William III (1650–1702; reigned from 1689). It depicts the moment before the horse stumbled on a molehill, ultimately causing the king’s death. During the Second World War, the Canadian diplomat Charles Ritchie (1906–95) brought a girlfriend here. Their canoodling was interrupted by a passerby who warned them of an unexploded bomb in the park.[45]

Circling around the square, we come to Charles II Street. Just beyond at the corner of Regent Street is British Columbia House (1 Regent Street), once home to the province’s agent-general in London.

Trivia: Colonel Reuben Wells Leonard (1860–1930) was a wealthy Ontario businessman, who gave money to purchase 10 St. James’s Square and named it in honour of his hero William Pitt, Earl of Chatham.

Prince Arthur (1850–1942), Duke of Connaught, laid the cornerstone of the building. He was the seventh of Queen Victoria’s nine children and Canada’s most royal governor general when he served in the post from 1911 to 1916. A career military man, he had defended Canada against Fenian raiders in 1870 and, into his nineties, was ready to take up arms again to fight the Nazis in the Second World War. Connaught also laid the foundation stone of Canada’s new parliament buildings in 1916.

British Columbia House: A Room with a View

British Columbia House was the brainchild of John Herbert Turner (1833–1923), a provincial politician known for extravagance when it came to spending the public purse. As finance minister, he never balanced a budget and ran up the province’s debt sevenfold by the time he left office. His opponents called his style of fiscal management “Turnerism” — like socialism or communism. When he sued once for libel, he lost.

If profligacy wasn’t bad enough, Turner frequently used his position and influence to feather his own nest. This got him into hot water so many times his government sent him to London as the province’s representative in 1901 to escape further controversy. But it was hard for the old dog to learn new tricks and he was soon bent on spending again, this time constructing a permanent symbol of his much beloved British Columbia in London.

Turner bought an old hotel on Regent Street and had it redeveloped by one of London’s pre-eminent architects of the day, Sir Reginald Blomfield. Not only was the result a fine building with the flourishes of a hunting lodge in the Rockies, it also came with a penthouse apartment with an equally fine view over London’s parks. Unfortunately, Turner’s luck finally ran out just as he was about to move into his new digs. In 1915, another agent-general was named by the province and Turner never had the chance to enjoy the beautiful apartment — or the view.

Continuing back in St. James’s Square, a plaque at number 31 tells us that this was the site of Norfolk House, once home to the Duke of Norfolk and later site of the First Allied Force Headquarters from 1942–44. Operation Overlord, the code name for the invasion of Europe in the Second World War, was planned here.

In movies like Saving Private Ryan, you would be forgiven for thinking D-Day was a purely American enterprise. But Canadians shared in every aspect of the operation and were assigned Juno Beach, one of the toughest of the five assault beaches in Normandy. Despite strong German defences and resistance, Canadians penetrated farther inland than any other Allied division during the first day. The enormous cost of over a thousand Canadian lives was half of what Allied planners had expected.

Less august battles also unfolded here. In 1937, Canada and other Commonwealth countries met at Norfolk House to plan the coronation of King George VI. An issue arose over what to wear to the event. Canadian officials in Ottawa balked at the idea of donning stockings and knee breeches — official court dress — though, not surprisingly, the anglophile Vincent Massey, Canada’s high commissioner, didn’t. “I wish to goodness some of my fellow countrymen wouldn’t have an almost religious antipathy to knee-breeches,” he said.[46] But sensing a wind of change, the British backed down. “We don’t want to break up the empire for the sake of a pair of trousers,” one said.[47]

Let’s leave St. James’s Square now and return to Pall Mall. Directly across from us are two Italianate masterpieces of architecture: the Travellers Club, built in 1832, and the Reform Club, built in 1841 (102 and 104 Pall Mall). Sir Charles Barry (1795–1860), Britain’s leading architect, designed both of them. Classical, confident, and elevated above street level, the pair exude the ideals of democracy and respectability but with a hint of superiority. When the old Tory rulers of Toronto set out to build Osgoode Hall for their law society, they modelled it in the manner of these clubs. “It expressed the cult of pretensions of the English upper class,” an architectural historian has written. “It was a trend in English society and the builders of Osgoode Hall were trying to emulate it.”[49]

I lunched on gammon at the Travellers club and afterwards read a pornographic book in the library. It is the most beautiful room in London. We used not to have any sex in the club library but now it is everywhere, like petrol fumes in the air. —Canadian diplomat Charles Ritchie, January 1969[48]

In popular culture, the Reform Club is best known as the place where Phileas Fogg took his wager to circumnavigate the globe in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days. Our interest, however, lies not so much with fiction as foundation. That’s because the club was founded in 1836 by a group of political reformers who wanted democratic changes in Britain and places like Canada. Long before there was a Preston Manning (b. 1942) or his Alberta Reform Party, these early reform ideas took root in Canada and led to its independence.

Beginning reform is beginning revolution. — Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

In the late 1600s, England had a parliament but not really a democracy. Members were either landowning aristocrats or later simply bought their seats in voterless ridings called pocket or rotten boroughs. But revolutions in the United States and France, as well as simmering discontent in Britain, fuelled a desire to broaden the definition of who could vote. In 1832, a parliamentary group of Whigs and Radicals united to pass the Great Reform Act — the first step toward democracy in Britain.

Similar ideas spread to Canada where a growing number of merchants were disenchanted with the rule of British governors and their Tory friends. Rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada in 1837–38 led by William Lyon Mackenzie (1795–1861) and Louis-Joseph Papineau (1786–1871) respectively signalled the need for change. As we learned on Walk 1, Britain sent one of its leading Reformers to find a solution: John “Radical Jack” Lambton (1792–1840), 1st Earl of Durham. He was a founding member of the Reform Club and advocate for greater self-government in Canada. A portrait of his handsome figure still watches over members dozing in the afternoon sunshine in the upstairs gallery.

Durham isn’t the only early club member with ties to Canada. Beside his portrait in the upper gallery is one of Sir Charles Poulett Thomson. Thomson was a Whig and fiscal reformer who succeeded Durham as governor general of Canada. His mission was to unite Upper and Lower Canada as part of his predecessor’s plan.

Reform Club: Chicken à la King

Charles Edward Poulett Thomson wasn’t an aristocrat but he ached to be one. The son of a timber merchant, he admired the upper classes and went out of his way to behave like a proper gentleman. His father’s ego may have been partially to blame. In 1820, John Thomson added Poulett to the family name, lending it a double-barrelled air of aristocracy. “He is very good humoured, pleasing and intelligent,” said a contemporary of the younger Thomson, but he is “the greatest coxcomb I ever saw, and the vainest dog.”[50]

Like many young men unable to succeed elsewhere, Thomson ran for Parliament. Mocked cruelly in the House of Commons as an effeminate bore, he had a talent for numbers and surprised everyone by becoming the de facto head of Britain’s Board of Trade. In 1839, he was asked to be governor general of Canada to implement Durham’s recommendation to unite Upper and Lower Canada. Thomson accepted on one condition: he be ennobled as an aristocrat if he succeeded.

Marrying Upper and Lower Canada was easier said than done, however. Frustrated with colonial bickering at every turn, Thomson soon regretted the deal he had struck back in London. He wrote in despair: “I would not stay here if they made me Duke of Canada.” Quebeckers never took to him — they called him le poulet (the chicken) — and Torontonians were not much fonder. They only agreed to unite with Lower Canada when Thomson offered to pay off their debts. To their wounded civic pride, however, he chose Kingston, Ontario, as the new capital of the united Province of Canada, claiming Toronto was “too far and out of the way.”

With his mission accomplished, Thomson at last sought out his coveted reward. But when he suggested the title “Lord St. Lawrence,” his superiors balked, believing it a bit too grand. Favouring something farther and more out of the way, they made him Lord Sydenham and Toronto instead.[51]

At the foot of Regent Street, we reach an open space known as Waterloo Place. On our left is the Guards Crimea Memorial by John Henry Foley and Arthur George Walker. It commemorates the more than two thousand British soldiers who died fighting Russia in the Crimean War (1853–56). On the south side of the monument is a bronze statue of Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), “the lady with the lamp.” Nightingale enlisted thirty-eight women to provide care to the sick and wounded in the Crimean War and broke a longstanding taboo against women on the front lines.

Jean [Chrétien] and I lunched at the Reform Club…. Jean was thrilled. He is full of the political life and aspires, as he should, to go to the top. — Paul Martin Sr., December 1976[52]

Whether in the flesh or in bronze, it seems she had a knack for providing comfort. Early in the Second World War, Vincent Massey and his wife, Alice, were crossing Waterloo Place when they heard the whistle of a German bomb and dove for cover. When they stood up and brushed themselves off, they found themselves at the foot of Nightingale’s statue. Massey wrote it was a comforting symbol he always remembered.[53]

Although no Canadian military units fought in the Crimean War, a number of Canadians enlisted individually. Lieutenant Alexander Dunn (1833–68) was one of these and became the first Canadian to win the Victoria Cross, the highest military award in the British Empire. He received it during the doomed charge of the Light Brigade in 1854. A monument erected in St. Paul’s Cemetery in Halifax in 1860 to commemorate two other Canadians in the Crimean War is said to be one of the oldest war memorials in the country.

Maritime names: In 1784, New Brunswick was named after King George III, who was also Duke of Brunswick. Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, was named after his homely wife, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744–1818).

Let’s cross now to the south side of Pall Mall at Waterloo Place. Continuing on, we come to Haymarket, with the New Zealand High Commission’s midcentury skyscraper on the corner.

Where Pall Mall divides right and left into Pall Mall East and Cockspur Street stands an equestrian statue, by Matthew Coates Wyatt, of the hatless King George III (1738–1820; reigned 1760–1811), America’s last British king and, practically speaking, Canada’s first. Cross over here at the traffic light.

George III came to the throne in a blaze of glory after the final conquest of Canada in 1760. The exit of his elderly grandfather George II blazed in a different way. He died from a stroke brought on by his exertions on the toilet.

As the king who lost the American colonies, history has been unkind to George III. What is often overlooked is that he was a hardworking and dutiful king who was forced to increase taxes on American colonists to pay for the war against the French in Canada. He is also remembered for his madness — later diagnosed as porphyria, a disorder of the nervous system — which landed him in a straightjacket in 1811 and his ne’er-do-well son on the throne as regent. Poor George III spent his last years out of his mind: deaf, blind, and bearded, playing the harpsichord and talking of men and women long since dead.[54]

An equestrian statue of King George III stands on Pall Mall East. Perhaps the first and finest likeness of the mad king (above), however, was found down a Montreal well.

Although Roman Catholics had limited rights in Britain, George III was a realist when it came to Canada. By signing the Quebec Act of 1774, he recognized the authority of the Catholic Church in Quebec, as well as the use of French civil law. In doing so, he helped lay the foundation for the Canada we have today. While the Quebec Act won the loyalty of French Canadians, it infuriated the Americans. They called it one of the crown’s “intolerable Acts” provoking their revolution.

King George III Monument: Le pape du Canada

In Montreal’s McCord Museum is a fine marble bust of King George III dated 1765 — carved by the noted British sculptor Joseph Wilton (1722–1803) and believed to be the first likeness of the new king. How it got there is one of the city’s most remarkable tales.

In 1765, after a fire devastated part of Montreal, a wealthy British merchant and philanthropist named Jonas Hanway (1712–86) led a fundraising drive in London to help rebuild the city. He sent over two fire pumps to help the stricken city, as well as a gift slightly less useful in terms of putting out fires. In fact, it may have helped start one: a fine marble bust of King George III.

The bust was displayed on a pedestal in Montreal’s Place des Armes. In 1775, only two years after it was unveiled, it was defaced with tar and adorned with a bishop’s mitre and rosary made of potatoes. Written on the rosary’s cross was: Voilà le pape du Canada et le Sot Anglois (Here is the pope of Canada and the English sot).

The vandalism outraged Montrealers and accusations of who was responsible flew from every quarter: French Canadians blamed English-speakers, Protestants blamed Catholics, and even some Jews were fingered. But the vandals were never caught. Then, in 1776, after the bust was cleaned up and returned to its public place, it disappeared for good after marauding American Revolutionaries attacked the city. For fifty years the whereabouts of George’s head was a mystery, until 1834 when workers found it in an old well in the square where the American soldiers had presumably tossed it — still remarkably well preserved in its own facial mud pack.[55]

Salada tea man Peter Larkin greets Queen Mary and King George V at the opening of Canada House in Trafalgar Square in 1927. The king is said to have admired Larkin’s office more than his own.

Keep now to the right and follow Cockspur Street for a few more metres until we reach the heavily colonnaded steps of Canada House. It was designed by the neoclassical British architect Sir Robert Smirke (1780–1867), who also designed the British Museum. This is Canada’s most prominent piece of foreign real estate, popular with both Canadian backpackers and — more often than not — protesters against the oil sands and annual seal hunts. It is a fitting place to end our walk through London’s clubland as it was once a club itself. That it now belongs to Canada owes much to a self-made man people called the Tea King of America or “Lord Salada.”

Canada House: A Club of One’s Own

Peter Larkin (1855–1930) was a tall and dapper millionaire who rose from humble origins to head the largest tea empire in North America. He owed the success not only to his special blend of Sri Lankan and Indian tea but to the discovery that foil packaging kept it fresh longer. In 1890, he created the Salada Tea Company and made a fortune promoting his drink through the new medium of mass marketing.

In 1921, Larkin arrived in London as Canada’s fifth high commissioner. He carried with him an important mandate from Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King: find a home suitable to represent Canada in the city.

Larkin’s long search at first centred on Trafalgar Square, known informally then as “Little Canada” with many Canadian banks and railway and insurance offices located there. He immediately set his sights on the prominent but financially ailing Union Club. Its membership had once included the School for Scandal playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751–1816), the wealthy businessman Cecil Rhodes (1853–1902) and the author Charles Dickens (1812–1870), though Dickens died the day he was elected a member. But in a city known for high-priced lawyers, the club made a fatal mistake that may have precipitated its decline: it barred lawyers from joining. And no one likes to buy an expensive club lunch more than an expensive club lawyer.

While the Union Club bickered over the sale, Larkin did consider other buildings. British Columbia House was a good choice but the province’s man wouldn’t give up his apartment and view. Another deal fell through when Nova Scotia’s agent-general wanted a hefty finder’s fee. “I am quite sick of this endeavour to obtain a home for ourselves in London,” Larkin wrote in frustration to his prime minister.

When the Union Club finally agreed to sell Larkin faced his last hurdle: what to call the impressive building. Although “Canada House” was the most obvious name, Mackenzie King didn’t think the term “house” quite grand enough. In deference to his wishes, only the name Canada was engraved above the door. When King George V opened the building in 1925, he is said to have told Larkin that his office was the finest in London, better than his own.[56]

We now find ourselves in Trafalgar Square, where our walk ends.