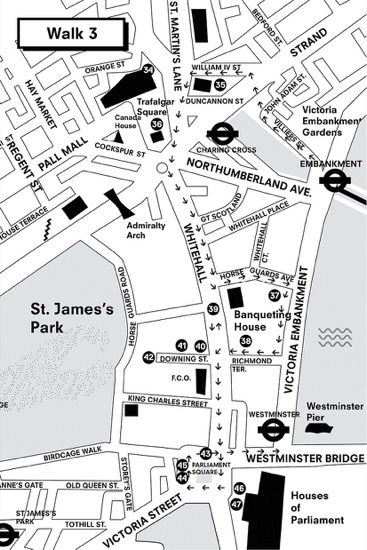

Walk 3:

Trafalgar Square and Whitehall

There’s something theatrical about this part of London even if it isn’t known for West End shows. Trafalgar Square appears like an outdoor opera set from behind the curtain of Admiralty Arch, while in Whitehall grandees cast in bronze seem poised to launch into plummy soliloquies like actors in the wings. Parliament, too, is known for its occasional dramas. Make no mistake about it; this area is London’s theatre of state.

This walk begins at Embankment Tube Station and ends at Parliament Square (nearest Tube stop: Westminster.) Walking distance is about 1.2 miles (2 kilometres).

A Short History of the Area

In medieval London, the village of Charing Cross lay just outside the Tudor palace of Whitehall, a ramshackle maze of buildings and courtyards dating from 1514 and sandwiched between the River Thames and St. James’s Park. The origin of the name Charing is a matter of dispute. It may take its name from either French (chère reine for dear queen), a reference to Queen Eleanor (1241–1290), wife of King Edward I (1239–1307; reigned from 1272), whose funeral cortege rested here for the night, or more likely from Anglo-Saxon (cerr) meaning a turn or bend in the river. In either case, the village lay on an important ancient road that ran from the city of London through Whitehall Palace to Westminster Abbey.

From its earliest days, Charing Cross has been associated with demonstrations and dissent. In Tudor times, this is where dangerous rebellions gathered and, during the English civil war and its aftermath, where beheadings took place. It’s ironic today that Trafalgar Square continues to be a site of protest for anyone with a modern axe to grind, so to speak. In the 1800s, demonstrators included anti-machine Luddites and suffragettes; in the century that followed they were Welsh miners, Irish nationalists and just about everyone else.

Whitehall Palace, on the other hand, was a place where swords and dissent were forbidden. It was originally occupied by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (ca.1475–1530), an influential mover and shaker in the Tudor world who lived lavishly for a man of the cloth: his “fayre house,” made of white stone, stretched over 22 acres (nine hectares) from Northumberland Street to Downing Street. When Wolsey fell from favour for failing to convince the Pope to grant a divorce to King Henry VIII (1491–1547; reigned from 1509) in 1529, the king confiscated Whitehall and the rest of Wolsey’s property. Perhaps to impress his subsequent five royal wives, Henry made numerous home improvements to Whitehall, including the addition of tennis courts, galleries, a bowling alley, and a cockpit. When he finally stopped building, the palace was said to contain 2,000 rooms. In one of these an exhausted Henry Tudor died in 1547.

Trafalgar Square is a much more recent addition to the area. Once a royal stable yard, it was cleared for a public square in 1830 by John Nash (1752–1835), the architect behind Regent Street and St. James’s Park. Nash didn’t live long enough to see it completed, however, and the lion’s share of the work fell to his successor, the architect Sir Charles Barry (1795–1860). Barry battled city officials to lower the elevation of the square to make the National Gallery appear larger and more grand. He battled against the blight of Nelson’s column too, but lost.[1]

The Walk

Exit Embankment Underground Station on the side of Villiers Street. To our right hidden from view is Victoria Embankment Gardens, a lovely if often crowded place to relax near the river when the weather cooperates. The Victoria Embankment runs 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometres) from Blackfriars Bridge to Westminster Bridge. It was designed from reclaimed land in the 1860s by Sir Joseph Bazalgette (1819–91) to accommodate one of London’s first major sewers. The York Watergate found in the park was constructed in 1626 and was once a private entranceway on the edge of the old riverbank. A weathered crest on it is that of the local Villiers family.

A great sleepiness lies on Vancouver as compared with an American town; men don’t fly up and down the street telling lies, and the spittoons in the delightfully comfortable hotel are unused…. — Rudyard Kipling, 1899

George Villiers (1592–1628), 1st Duke of Buckingham, was a court favourite associated with two successive monarchs: King James I (1566–1625, reigned from 1603) and his son King Charles I (1600–49, reigned from 1625). King James famously bragged “Christ had his John, and I have my George.”[2] Villiers lived in a house that once stood here. The narrow lane that runs alongside the subterranean Gordon’s Wine Bar is Watergate Walk, once a waterfront promenade.

Walk up Villiers Street, a busy commercial area lined with food shops for city commuters. In 1889–91, Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936), the Nobel Prize-winning poet and author of The Jungle Book and other stories, lived at number 43 (at the time number 19), above what was then Harris the Sausage King. Although Kipling married an American, he preferred Canada to the U.S. He visited Vancouver three times but failed miserably at the local pastime: real estate speculation.

Trivia: In 1922, Rudyard Kipling devised the initiation for professional engineers in Canada, known as the “Kipling Ritual.” During the ceremony, new graduates are presented with an iron ring to symbolize humility and pride in their profession.

At the top of Villiers Street we come to the Strand, which runs from Trafalgar Square to the west and to Fleet Street in the historic City of London to the east. The Strand is the Old English name for shore. On our left, in the forecourt of the railway station, is the ornate cross that gives the area its name.

Cross over the Strand by Charing Cross at Duncannon Street. Ascend the pedestrian walkway past a ghoulish monument to Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) and turn left on William IV Street at the Post Office. At the next corner is a 1920 marble memorial by Sir George Frampton to the British nurse Edith Cavell (1865–1915), who was shot during the First World War for helping British and Allied soldiers escape German-occupied Belgium. The execution of the patriotic Cavell (rhymes with gravel) enraged the Allies. Many newborn girls were named Edith as a mark of respect (among them the French singer Edith Piaf). In Canada we did one better and named a mountain after her (Mount Edith Cavell in Jasper National Park).

Just beyond Cavell’s monument is the National Portrait Gallery. It opened in 1896 and displays the faces of Britain’s most accomplished men and women. Originally, only the portraits of those who had been dead ten years or more were displayed, but in the permissive 1960s this and many other rules were relaxed. Today, you’ll find more current celebrity faces here than on a magazine rack at Chapter’s. For this reason some unkind locals have dubbed it “Madame Tussaud’s for the middle classes.”

Trivia: Sir Christopher Ondaatje was born in Kandy, Sri Lanka, and emigrated to Canada when he was twenty-two. He took to winters like Maurice Richard to ice and won gold for Canada at the 1964 Innsbruck Winter Olympics in the team bobsled event. He went on to make his fortune in finance.

The gallery houses some 160,000 portraits, though thankfully for those with limited time only a portion are on view. Many of the figures portrayed played a part in Canada’s history. It’s a shame visitors have to come halfway around the world to see them here rather than in our own national portrait gallery. With luck, someday this may change.

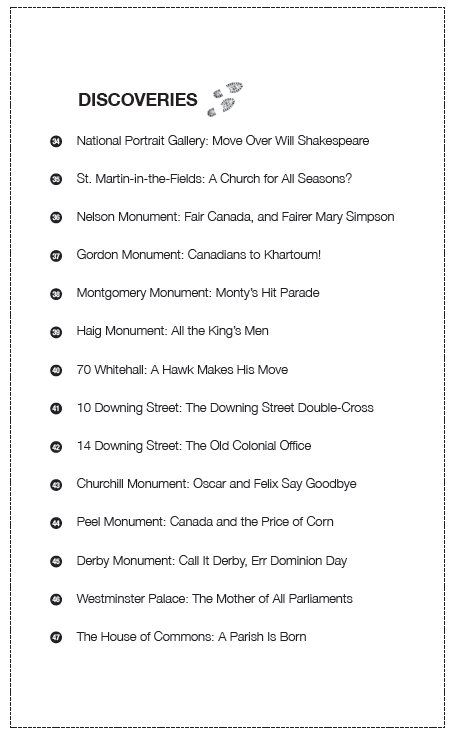

Will the real Bard please stand up? The Sanders portrait of William Shakespeare is the Canadian contender in the great “battle of wills” to find a likeness of the famous playwright.

Just beyond the gallery’s revolving front doors is the Ondaatje Wing. It’s named not after the Canadian novelist Michael Ondaatje (b. 1943) but his older brother and gallery benefactor, the financial tycoon Sir Christopher Ondaatje (b. 1933).

Now every country arguably has its own Mona Lisa or defining painting. In Britain, the equivalent is found here in the National Portrait Gallery. In 1856, Francis Egerton (1800–57), 1st Earl of Ellesmere, donated his famous portrait of the playwright William Shakespeare (ca.1564–1616). It’s known as the Chandos portrait or simply as “NPG1.” For years, this pirate-like figure with a gold earring was believed to be the truest painted likeness of the Bard. But in 2002 a rival from Canada appeared on the scene to rattle Britain’s Shakespeare establishment. It challenged mainstream opinion about who Shakespeare was — or, perhaps more accurately, the notion that we will ever really know.

National Portrait Gallery: Move Over Will Shakespeare

Nobody knows if Shakespeare ever sat for a portrait, but as a successful and wealthy poet and playwright in Elizabethan England, it is possible, nay probable, that he did. Of the likenesses that exist, only a line drawing published in his complete works and a plump funeral bust in Stratford-upon-Avon are thought to be the most credible as they were likely supervised by people who knew him. The trouble is both are cartoonish and lack depth. Lovers of Shakespeare crave more.

Thus the search for a portrait of Shakespeare began. Over the years, a number of contenders have emerged from flea markets and family estates. Of these, six portraits are thought to be the most worthy as they can be traced back more or less to the poet’s lifetime. None, however, is categorically the real McCoy.

The world of Shakespeare went topsy-turvy in 2002 when Lloyd Sullivan, a retired engineer and part-time bus driver from Ottawa, Ontario, went public with an old family heirloom: a painting dated 1603 known as the Sanders portrait of Shakespeare. Sullivan says this likeness was painted by his ancestor John Sanders. The painting came to Canada from Britain in 1919. Unlike the other portraits, his doesn’t depict a balding, accomplished gentleman but rather a young, rakish man with reddish-brown hair and a wry, knowing smile.

While detractors say the image is much too young to be the Bard in 1603, when he was thirty-nine and middle aged for the times, the painting has caused a lot of fuss. First, it has a long family history and can be traced to Shakespeare’s lifetime. Uniquely among the main contenders, it also comes with a label. This is of similar age to the portrait and uses the spelling “Shakspere,” which the Bard himself used. It is also dated 1603, a fact confirmed by tests. Researchers have also linked Sullivan’s family to the Bard’s, suggesting a plausible reason for the Sullivans to possess such a portrait in the first place.

But perhaps the oddest argument in favour of the Canadian contender is the sitter’s left ear. If the line engraving of Shakespeare found in his published works is the accepted lifetime likeness, then Shakespeare had attached earlobes. Sullivan’s Canadian portrait shows this. The Mona Lisa of the NPG doesn’t.[3]

Leave the National Portrait Gallery and follow the crowds down St. Martin’s Place to Trafalgar Square.

To our left on the southeast side of the square is the colonnaded church St. Martin-in-the-Fields, designed by the Scottish architect James Gibbs (1682–1754). Gibbs trained to be a priest in Rome but switched to more earthly pursuits after he fell in love with baroque architecture. In 1709, he came to London to practise his trade and was mentored by the extraordinary architect Christopher Wren (1632–1723).

Shakespeare was a savage who had some imagination. He has written many happy lines; but his plays can only please in London and in Canada. — French philosopher François-Marie Voltaire, 1765

Trivia: Established in 1570, London’s Whitechapel Bell Foundry is Britain’s oldest manufacturing company. It cast the Great Bell of Montreal’s Notre-Dame Basilica and the eight bells of Quebec City’s Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral.

Look at St. Martin’s and you’ll see an ornate, wedding-cake steeple set on top of a Roman temple. Gibbs was as famous for his steeples as he was for where he put them. Before Gibbs, steeples were usually attached to churches at the side or front. But St. Martin-in-the-Fields is interesting for another reason: it’s the most copied church in Canada and the United States.

In 1728, Gibbs published his design for St. Martin-in-the-Fields and other churches in a celebrated work called A Book of Architecture. It was a sort of emblem of respectability with British settlers in North America. But these migrants didn’t just display the book on their coffee tables for visitors to admire. They built what was in it.

One of these settlers was likely Governor Edward Cornwallis (ca.1712–76), the founder of Halifax, Nova Scotia, who came to Canada in 1749.[4] Certainly, St. Paul’s Church in Halifax, which dates from 1750 and is the oldest surviving Anglican church in Canada, was heavily influenced by Gibbs’s book. So too were the Charlotte County Court House in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, and many other buildings in Canada. But the most striking copy of St. Martin-in-the Fields can be found in the heart of French Canada. If visitors to Quebec City think the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity seems oddly out of place, it was designed to be.

Imitation, they say, is the best form of flattery: St. Martin-in-the Fields by the architect James Gibbs is the most widely copied church in North America.

St. Martin-in-the-Fields: A Church for All Seasons?

After the fall of New France, Canada’s new British rulers wanted their citizens to embrace Protestantism. But the more pressing need to keep French Canadians loyal during the American Revolution delayed their religious zeal. With the war lost, in 1793 they forged ahead with their plans and created an Anglican diocese for Upper and Lower Canada based in Quebec City.

The man chosen to head the new diocese was a proud and uncompromising Norfolk vicar named Jacob Mountain (1749–1825). In 1793, he was consecrated bishop at Lambeth Palace in London and sent to Quebec. When he discovered to his horror that his new congregation worshipped in a Roman Catholic church amid “crucifixes, images and pictures of saints,” he set about quickly building his own.[5]

Mountain determined that nothing about his new Anglican cathedral — workmen, materials, nor design — would be French. So he built the most English church he could lay his fingers on: Gibbs’s St. Martin-in-the-Fields.[6] But it was French Canadians who enjoyed the last laugh. St. Martin’s may have been a symbol of Quebec’s new rulers, but it was poorly designed for Quebec’s winters. Maybe if Mountain had followed the building codes of the Ancien Régime and kept the pitch of his new roof to a steep angle, he might have saved his cathedral some trouble. No sooner was his cathedral finished when he had to redo the roof to keep it from collapsing from the weight of snow. It was a lesson French Canadian builders — but evidently not London architects — knew only too well.

When Mountain died in 1825, he was buried under the chancel of his beloved cathedral. His epitaph said he was the “Founder of the Church of England in the Canada,” but in many ways Wren’s epitaph in St. Paul’s Cathedral would have been equally fitting: “If you seek his memorial, look around you.”

Now let’s head into Trafalgar Square, the vast tribute to Britain’s sea power, keeping to the left side. At one time you would have dodged traffic to do this but in 2003 a large pedestrian terrace was created in front of the National Gallery as part of a redevelopment of the square.

Trivia: Begun in 1800, the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Quebec City was the first Anglican cathedral to be built outside of Britain.[7]

During an earlier redevelopment in 1939, Barry’s original red-granite fountains, admired by Londoners for a hundred years, were removed and re-gifted to Canada. They now splutter 1,400 miles (2,200 kilometres) apart: one in Regina and the other in Ottawa.

Nelson’s column dedicated to Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758–1805), 1st Viscount Nelson, who died at the Battle of Trafalgar, towers in front of us.

Trivia: Montreal merchants erected a monument to Viscount Admiral Horatio Nelson in 1809, thirty-four years before Londoners did. It stands somewhat incongruously in Place Jacques Cartier.

Although a naval genius, Nelson was rash, cruel, and famously short-tempered. He was also very hot-blooded. “Pray do not let your fascinating Neapolitan dames approach too near him for he is made of flesh and blood and cannot resist their temptation,” a naval official once warned the wife of the British ambassador in Naples to no avail.[8] It was a pattern of destructive behaviour that may have first manifested itself in Canada.

Nelson Monument: Fair Canada, and Fairer Mary Simpson

In April 1782, Nelson was ordered to escort a convoy of ships to resupply the British garrison at Quebec City. He didn’t want to go. Small, thin, and often unwell, the young Nelson worried the cold North Atlantic climate would do him more harm than good. He was right. When his fleet arrived in Newfoundland, the cold, thick fog penetrated to his very bones with a numbing chill. Compounded by scurvy, his health deteriorated.[9]

Quebec City, however, offered a welcome respite from damp St. John’s. On his arrival inland, Nelson wrote to his father: “Health, that greatest of blessings, is what I never truly enjoyed until I saw Fair Canada. The change it has wrought I am convinced is truly wonderful.”

Nelson’s change of heart wasn’t just due to a change in the weather. At a garrison ball, Nelson set sights on young Mary Simpson, the daughter of the provost-marshal of Quebec. Simpson was a striking girl, attractive and well-educated and about two years Nelson’s junior. It wasn’t long before this flesh-and-blood man was ready to abandon the Royal Navy for the woman he loved. “I find it utterly impossible to leave this place without waiting on her whose society has so much added to its charms and laying myself and my fortunes at her feet,” he reputedly said.[10]

It’s folly but fun to imagine what might have happened if Nelson, who ultimately vanquished Napoleon at sea in 1805, had followed his heart and settled in Canada. Would we now be standing in Trafalgar Square or Place de l’Empereur? Alas, no wedding bells chimed for Nelson and his Quebec City belle. While ascending the steep streets from Lower Town to propose to her, Nelson was persuaded against his folly by a friend. He gave up his pursuit and sailed with his ship before the ice set in on the river. He never saw his first love, Mary Simpson, again.[11]

Before we leave Trafalgar Square, let’s fast forward to the twentieth century. As a young correspondent for Radio-Canada, the future premier of Quebec, René Lévesque (1922–87), stood here to report on the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953. Before the state coach passed on its way to Westminster Abbey, Lévesque filled five hours of radio time for French listeners back home. “What followed was one of the great performances in the history of radio,” he recalled. “Never had so much work been done for so little.”[12]

Now let’s make our way down the left side of Whitehall.

At the Banqueting House follow Horse Guards Avenue down to the River Thames, past the modern Ministry of Defence building completed in 1951. After a short walk we arrive back at the Victoria Embankment. Excavated in the grass behind the ministry are the Whitehall Palace steps that once led down to the river. It is believed that Cardinal Thomas Wolsey went down steps like these when he abandoned his home for King Henry VIII in 1529. So too did the executioner of King Charles I in 1649 with his axe.[13]

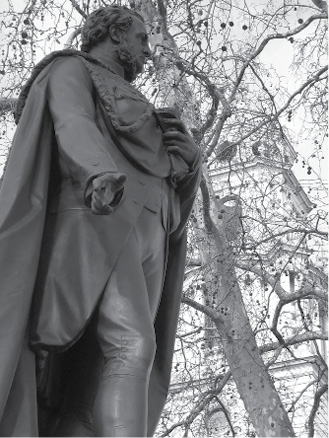

Near the Whitehall steps is a bronze statue by the sculptor Sir William Thornycroft of Major-General Charles Gordon (1833–85). This nineteenth-century British hero holds a bible under one arm and rests his foot on a cannon. Gordon was a half-mad Christian soldier with icy blue eyes and wildly eccentric beliefs. His statue originally stood in Trafalgar Square but now languishes here largely forgotten, but not by us.

Trivia: Field Marshal Sir Garnet Wolseley was the inspiration behind Gilbert and Sullivan’s “model of a modern major general.” A statue of Sir Garnet stands across Whitehall in Horse Guards Parade.

In early 1884, Gordon was sent to evacuate Egyptian forces loyal to Britain in Sudan. He was supposed to accomplish this mission peacefully but things didn’t go according to plan. When he and his forces became trapped by rebels in Khartoum, he took up arms to defend the city rather than abandon it. British voters called out for his rescue and the government reluctantly agreed.

Now what you might ask has Canada got to do with a wayward crusader in faraway Africa? Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald (1815–91) wondered that too. When Britain called for soldiers across the British Empire to rescue Gordon, Canada’s “Old Tomorrow” declined to get involved. But that didn’t stop some citizens from going.

To rescue Gordon, the British Government appointed Field Marshal Sir Garnet Wolseley (1833–1913), at the time the most famous soldier in Britain and widely believed to be the only man up to the task. That’s because some fifteen years earlier, Wolseley had led a dramatic 620-mile (1,000-kilometre) expedition up the Red River in Manitoba to put down Louis Riel’s rebellion at Fort Garry (now Winnipeg).

Wolseley believed the fastest route to Gordon was by another river, the Nile — and the only people who could get him there were the hearty voyageurs he had relied on so ably in Canada. The fact the two rivers were very different didn’t concern him. “Water is water,” he said blithely. The Gordon Relief Expedition to Africa in 1884–85 would become the first overseas expedition undertaken by Canadians.

Gordon Monument: Canadians to Khartoum!

The hardy Canadian voyageurs who had paddled Wolseley up the Red River in 1870 were, by 1884, a vanishing breed. The railroad had put many out of work and those who had kept paddling Canadian rivers were getting a bit long in the tooth. “The Red River men naturally are rather past their prime,” responded an official in Ottawa to Wolseley’s request for his old crew. Instead, the official advertised for lumbermen who worked on the Ottawa, Gatineau, and Saguenay rivers: “Good boatmen to accompany English Expedition up the Nile, to steer boats through the rapids and do all necessary portaging,” it said.[14]

For the boatmen, the opportunity of a six-month contract and foreign adventure to Africa was too good to pass up. Within a month, some 400 volunteers were on their way to Egypt, including one as old as sixty-four. They hailed from Ottawa, Winnipeg, Trois Rivières, Sherbrooke, and the Kahnawake territory on the St. Lawrence River. At the helm was thirty-seven-year-old Frederick Denison (1846–96), a wealthy Toronto lawyer, politician, and veteran of the Red River Campaign. “What with Canadian men, Canadian officers, Canadian clothing, and the best Canadian tobacco, Gordon is safe,” proclaimed the Hamilton Times.[15]

But for all his confidence, Wolseley had badly misjudged the situation. For starters, the cataracts on the Nile came in quick succession and the current was so strong the men rowed for hours without advancing. Nor were Denison’s men the cheery voyageurs who had paddled to Fort Garry singing songs. They were a rough and argumentative lot and it wasn’t long before many got fed up and went home, leaving only a handful to haul the boats the rest of the way. This little group struggled for three months longer until the terrible news reached them: upriver Khartoum had fallen and Gordon was dead.

A year after it had begun, what remained of the Gordon rescue expedition returned home. Denison and his men were feted as heroes and Wolseley, like many military embarrassments, was promoted. Inside, however, he knew his status as Britain’s modern major-general was not only tarnished but over.

Walk through the gardens and return to Whitehall via Richmond Terrace.

In the middle of Whitehall is the memorial to the Women of the Second World War (2005), which echoes the Cenotaph a bit farther down the street. However, unlike the Cenotaph, this memorial isn’t decorated with flags but with the uniforms and working clothes worn by women.

The Dominion of Canada supplied us with a most useful body of boatmen. Their skill in the management of boats in difficult and dangerous waters was of the utmost use to us in our long ascent of the Nile. — Major-General Sir Garnet Wolseley[16]

On our immediate left in front of the Ministry of Defence is Raleigh Green, where a statue of Sir Walter Raleigh (ca.1552–1618) can be found. A number of other statues here continue our military theme.

Trivia: Sir Walter Raleigh, the famous pirate and privateer under Queen Elizabeth I, raided St. John’s, Newfoundland, in 1618, on his way to the West Indies. He plundered food, ammunition, and men for his ships.[17]

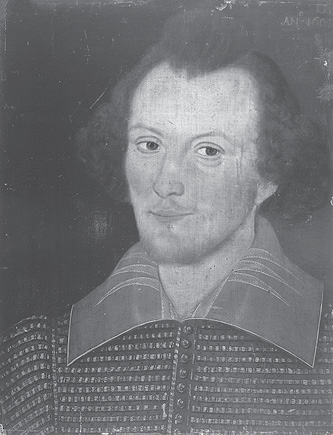

Our interest is a 1980 bronze statue of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery (1887–1976), 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, wearing his characteristic military beret. The statue is by the Croatia-born artist Oscar Nemon (1906–85) whose statue of Winston Churchill stands near Toronto’s City Hall.

British General Bernard Montgomery, or “Monty” to his troops. He was so austere he could have been a monk.

As an outstanding but difficult military leader, Montgomery was the man every soldier loved to hate. In the Second World War, he led Canadian troops in Italy, Sicily, and France. His admiration for Canadian soldiers, however, was matched only by his contempt for their commanders.

Montgomery Monument: Monty’s Hit Parade

General Bernard Montgomery, or “Monty” as he was popularly known, was so austere he could have been a monk. But he was also vain, nasty, and an outright liar — attributes which ruled out a career in the church, in theory at least. Instead, he joined the army and rose right to the top. When he took charge of South-Eastern Command during the Second World War, he put Canadian soldiers on a strict physical regime — and their commanders too. He gave the boot to those who didn’t live up to his expectations.

“I hope to be sending Price back to you,” Montgomery wrote slyly to Ottawa about one Canadian commander and former dairy farmer who didn’t make the grade. “He will be of great value in Canada where his knowledge of the milk industry will help on the national war effort.”[18]

Monty was particularly disenchanted with Canada’s General Andrew McNaughton (1887–1966). He believed the assertive McNaughton lacked the necessary mettle and experience in the field and is thought to have colluded with his colleague Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke (1883–1963), 1st Viscount Alanbrooke (whose statue stands nearby) to have Ottawa recall the Canadian. Instead, a badgered McNaughton retired in 1943.

But Montgomery got more than he bargained for next. McNaughton was replaced by General Harry Crerar (1888–1965), a Canadian who had more battle experience than McNaughton — and more pluck. Crerar may have been “no ball of fire” in Monty’s eyes but he knew at least what he was up against. An officer had warned him Monty was “an efficient little shit.”[19]

Predictably, it wasn’t long before that efficiency hit the fan. When Crerar declined a meeting with Montgomery in order to attend a memorial service at Dieppe, Montgomery flew into a rage. He called Crerar’s absence insubordination. But the Canuck wouldn’t be bullied. “There was a powerful Canadian reason why I should have been present at Dieppe that day,” Crerar said with the full backing of the Canadian Government. “In fact, there were 800 reasons — the Canadian dead buried at Dieppe Cemetery.”[20]

I fear he thinks he is a great soldier and he was determined to show it from the moment he took over command at 1200hrs on July 23. He made his first mistake at 1205 hrs; and his second after lunch. — British General Bernard Montgomery on Canadian General Harry Crerar[21]

Walk a few steps back up Whitehall toward the Banqueting House. Near to it is a controversial equestrian statue by Alfred Hardiman of an equally controversial equestrian general. This is the hatless Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (1861–1928), 1st Earl Haig, commander-in-chief of British and Empire troops in the First World War. His command included some 620,000 Canadian soldiers, about one in ten of whom never returned from the war. If Haig died a military hero, it wasn’t long before his detractors accused him of incompetence causing the loss of untold lives in France.

General Douglas Haig, supreme commander of British and Canadian troops in the First World War. One in ten Canadian soldiers never came home.

Trivia: During the Battle of Beaumont Hamel in 1916, the 1st Newfoundland Battalion suffered 700 casualties among 850 men. Observers said they were “mown down in heaps.”

Haig Monument: All the King’s Men

Douglas Haig was a twentieth-century general schooled in nineteenth-century warfare. As a young cavalry officer, he had fought in Sudan and South Africa and unfailingly believed that men and horses could beat machine guns. To many, this belief epitomized his failure to grasp the realities of modern warfare.

For Canadians, Haig was both hero and villain. While he sometimes supported the able Sir Arthur Currie (1875–1933), the leader of the Canadian forces, the two men were often at odds over how Canadians should be deployed. This was particularly true over the third Battle of Ypres, also known as Passchendaele.

In July 1917, Haig launched a third offensive against the enemy near the Flemish town of Ypres. The aim was to break the well-defended German line and then use cavalry to rush for the Belgium coast. The battle forever cast Haig as a commander who was stubborn, aloof, and insensitive to human loss.

The Ypres battlefield was a low stretch of ground reclaimed from the sea by dykes. After heavy rain and bombardments, the terrain became nothing but mud. For weeks British, Australian, and New Zealand troops fought the enemy with limited gains. In a final and frenzied effort to achieve victory, Haig ordered the Canadians to finish the job.

Currie didn’t agree. He warned Haig it would cost three-quarters of his men, but the supreme commander wouldn’t listen. “We ought to have only one thought now in our minds, namely to attack,” he said.

After horrific fighting, the Canadians miraculously broke through. Yet some 16,000 men died in the attempt and countless more were wounded. Overall, Haig’s victory claimed nearly 250,000 casualties on the British side. Obstinate as always, he never visited the carnage, though one of his senior army officers did. He wept as his boots sank deep into the muck. “My God,” he said. “Did we really send men to fight in this?”[22]

Trivia: In 1924, Field Marshal Earl Haig, commander-in-chief of British and Empire forces, unveiled the National War Memorial to Newfoundland’s war dead in St. John’s.

Turn and retrace your steps down Whitehall to Richmond Terrace. Down the street is the Cenotaph. The simple stone monument (cenotaph means empty grave in Greek) was erected in 1920 to commemorate those who died in the First World War. It is decorated with flags of the three services as well as the merchant marine. Sir Fabian Ware (1869–1949), founder of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, once calculated that if the dead of Britain and the Empire in the First World War were to march four abreast down Whitehall, they would take three and a half days to pass this monument. Over 60,000 of those dead marchers were Canadians.

Trivia: John McCrae (1872–1918), a Canadian army doctor, influenced the poppy’s adoption as a symbol of war remembrance with his poem “In Flanders Fields.”

Across the street at 70 Whitehall is the Cabinet Office, which coordinates government policy. It stands on the site of an old amphitheatre used in Tudor times for fighting cocks. The buildings constructed here afterward were familiarly known as the Cockpit. In March 1711, this was the scene of an assassination attempt with a surprising outcome for Canada.

70 Whitehall: A Hawk Makes His Move

Robert Harley (1661–1724), 1st Earl of Oxford, and Henry St. John (1678–1751), 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, were Tory politicians with big egos and cunning to match. Outwardly friends, in reality they were crocodiles and deep political rivals. During the War of the Spanish Succession with France (1702–13), Harley and St. John (pronounced sin-gin) occupied the most important posts in Queen Anne’s government: chief minister and war secretary, respectively. Together they faced mounting pressure to end the war with France but just how to do that set them at odds: Harley was a moderate and St. John a war hawk.

One day in 1711 Harley arrested a French émigré and well-known intriguer named Antoine de Guiscard in St. James’s Park. Guiscard had been a spy for the English but intercepted letters incriminated him as a double agent now working for the French. Harley had him brought to the Cockpit in Whitehall for questioning. St. John was there too.

As the interrogation ended, Guiscard lunged with a penknife at Harley, wounding him in the chest. Harley might have been more seriously hurt had he not worn several protective layers of clothing to stay warm. Still he bled profusely and sent word bravely to his sister not to keep dinner waiting for him.[23]

With Harley temporarily out of commission, St. John made his move. He swiftly set in motion a daring plan to end the war with France by launching an assault on Quebec with 5,000 of England’s best troops. The intent was to capture the French fortress and use it to sue for peace. For the daring mission St. John chose Sir Hovenden Walker and Colonel John Hill, elevating the latter to rank of general. But as we discovered on Walk 1, St. John’s plan proved a disaster: the ships foundered in the St. Lawrence and 900 men drowned. When Harley recovered, the queen granted him an earldom for his bravery — but St. John was left empty-handed.[24]

Trivia: Sir Robert Walpole (1676–1745) was Britain’s longest-serving prime minister. He served twenty years and 314 days. Canada’s Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King (1874–1950) broke Walpole’s record — serving twenty-one years in office — and remains the longest-serving PM in the Commonwealth.

Immediately next is Downing Street. In 1735, King George II (1683–1760; reigned from 1727) granted the house at number 10 to Sir Robert Walpole (1676–1745), who was effectively prime minister. It has been home to British prime ministers ever since.

When Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013) came to power in 1979 on a wave of industrial unrest in Britain, she hardly could have predicted that a former colony like Canada would stall her plans to reform the country. But the patriation of Canada’s constitution in 1980–82 threatened to do just that. How Canada’s pirouetting prime minister duped the “Iron Lady” is our next discovery in London.

10 Downing Street: The Downing Street Double-Cross

On June 25, 1980, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau arrived at 10 Downing Street to have lunch with Prime Minister Thatcher. Their politics and backgrounds couldn’t have been more different: she was a steely conservative grocer’s daughter focused on East-West tensions and he was a flamboyant social democrat focused on the North-South divide.

On the luncheon menu that day were Trudeau’s plans to amend Canada’s constitution — known as the British North America Act of 1867 — and bring it home from Britain. Trudeau needed Thatcher’s support because only the British Government could amend an Act of the British Parliament. Although Thatcher expressed concern that this might slow down her own Tory agenda she agreed, convinced by Trudeau it would be a simple matter. He left Downing Street beaming; she would later claim being tricked.

As the constitutional wrangling between Ottawa and the provinces dragged on in 1980–81, it became clear that passing Canada’s new constitution in Britain would be anything but straightforward. For one thing, many British MPs, encouraged by the lobbying of Quebec and others, threatened to take up valuable parliamentary time and stall Thatcher’s own legislative program. Nor had Trudeau mentioned between the courses that he might act unilaterally without the consent of the provinces. When British MPs expressed concerns about this, Trudeau told them to just hold their noses and pass his bill.

But what really upset the Iron Lady was Canada’s revolutionary Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Trudeau had not mentioned this to Thatcher, perhaps knowing it might spell trouble for her government, which opposed anything remotely French. The thought of Trudeau’s double-cross made her fume. “Do you have any idea what your prime minister told me?” she told an unnerved Albertan official. “He wanted my assurance it would go through quickly but he never mentioned a bill of rights!” She asked two of Trudeau’s ministers who were visiting the same thing: How could she support a charter of rights when British Tories were fundamentally against one?[25]

In the end, Trudeau’s constitution did get passed and Maggie carried on with her handbagging of British unions. On a rainy April 17, 1982, Queen Elizabeth II signed Canada’s new constitution and, as queen of Canada, acquired legal protection she lacked in Britain: Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Not one man in a thousand cares whether the Canadians prosper or fail to prosper. They care that Canada should not go the States, because — though they don’t love the Canadians, they do hate the Americans. — Phineas Finn by Anthony Trollope

If you peer through the security gates to the end of Downing Street you will see a wall, beyond which is St. James’s Park. Long ago, a rundown and obscure row house stood here that was, from Canada’s perspective, perhaps more important than the celebrated “Number 10.” It was 14 Downing Street — the old Colonial Office — where a clutch of Dickensian scribes administered Canada and the rest of the British Empire until the building was torn down in 1876. No place was more maligned by those demanding self-government in Canada than this damp and dreary little office that once ruled from the heart of Whitehall.

14 Downing Street: The Old Colonial Office

A Canadian visitor to London in the early 1800s would have been surprised to discover that they and the rest of the people in the British Empire were ruled mostly out of a shabby little building at the end of a cul-de-sac. The old Colonial Office was the main link between Canada and Britain. “Only in England,” an amazed official wrote, “could an important government department be housed in nothing more than a decent lodging house.”[26]

If its outward appearance left much to be desired, so did its interior. The building was a cramped, unkempt space that was so damp stoves had to burn year-round just to keep the heaps of papers dry. On the upper floors, dozens of well-meaning but indifferent bachelor scribes waited for dispatches to arrive from far-flung colonies. They would then set about registering, copying, annotating, and — in the fullness of time — maybe even answering them.

Yet the daily, unhurried routines of these faceless civil servants ran a quarter of the world’s population. They appointed governors and bishops, approved local laws and managed commerce and shipping. Colonial Reformers in Canada railed against this centralized control by Britain and demanded more autonomy. Workhouses for the poor were better administered, they claimed. After the rebellions in Canada in 1837–38, change did come about slowly, first in Canada, then in the rest of the British Empire.

Even after Confederation in 1867, the Colonial Office still exerted influence over Canada but it was increasingly more distant and out of touch. This was certainly the case when the Liberal politician Edward Blake (1833–1912) paid a courtesy call. Blake was a bitter political rival of Sir John A. Macdonald’s who had forced the prime minister’s resignation three years earlier over influence peddling. Sitting in the waiting room at the Colonial Office, Blake was met by a badly briefed official who greeted him cheerily with: “Well, I hope our friend Sir John Macdonald is getting along all right!”[27]

Continuing down Whitehall, the next building on our right is the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (or “FCO”), an Italianate palace built in 1861–68 to house the country’s diplomatic service. It was designed by the architect Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811–78). He would have preferred to build something in the Gothic style but in this part of town, even architecture is political. Gothicism was associated with the Tories and they were swept from power just before the FCO was built. So Scott revised his plans along more classical lines for the new kids in town.

The next building on our right between King Charles Street and Parliament Square is H.M. Treasury. At the back are the Cabinet War Rooms, built in 1936 to provide secure offices in the event of war. This warren of small, windowless rooms beneath thick concrete is much the same as when Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill (1874–1965), his War Cabinet and others used these rooms during the Second World War. It’s a fascinating place to visit with an excellent display on Churchill himself. It’s well worth a few hours to explore now or at the end of our walk.

Trivia: Sir George Gilbert Scott designed the Anglican Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in St. John’s, Newfoundland, in his much preferred Gothic style.[28]

At the end of Whitehall, we come to the Houses of Parliament. Cross over Westminster Bridge Road and into Parliament Square. The first memorial we come to depicts the incomparable Churchill himself. The son of an English aristocrat and American heiress, Churchill was a soldier, war correspondent, writer, and member of Parliament before becoming prime minister in the dark days of 1940. The 1973 bronze statue by Ivor Roberts-Jones depicts the wartime leader in a long military coat walking toward Westminster Bridge. His stern look of determination both inspired and embodied Britain’s bulldog spirit in the face of German Nazism.

Trivia: After visiting the prairies in 1929, Winston Churchill told his wife: “I am greatly attracted to this country” and contemplated leaving “the dreary field [of Britain] for pastures new.”[29]

Although Canadians universally admired Churchill, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King (1874–1950) was much less enthusiastic. In terms of character, upbringing, and political style, the two leaders were such complete opposites that they could have been nicknamed Oscar and Felix, or the Second World War’s Odd Couple.

Churchill Monument: Oscar and Felix Say Goodbye

On his last visit to London in 1948, an ailing Mackenzie King took to his bed at the Dorchester Hotel in Mayfair. A steady stream of dignitaries came to see him there, including the king, the prime ministers of Britain and India, and two London clairvoyants.

Churchill was the last to arrive, smoking a large cigar as usual. “I assume Mr. King will not object if I smoke while we are together?” he asked a Canadian diplomat at the hotel room door. Churchill had known King for nearly fifty years and likely knew his intolerance to such vices. The request terrified the diplomat. “I am afraid, Mr. Churchill, that Mr. King’s doctors have said smoke might have an injurious effect on his heart condition,” he lied. Churchill scowled his famous scowl. “Watch it,” he said placing his cigar in an ashtray, and went in to see King for the last time.[30]

British prime minister Winston Churchill’s statue in front of Parliament. He and Canadian prime minister W.L. Mackenzie King were such an odd pair they could have been cast in a Neil Simon play.

Although the same age, the two old warriors were oceans apart in character: Churchill was a gregarious titan who dreamed big, took risks, and drank famously —starting with a half a bottle of champagne every day. By contrast, the only spirits King tolerated were summoned at séances. He was a superstitious and cautious incrementalist who didn’t do anything by halves that he could do by quarters.

Indeed, their differences were probably at the root of King’s first suspicions about the British politician. “It is a serious business having matters in the hand of a man like Churchill,” he said early in their acquaintance. On the night Churchill became prime minister, King confided to his trusty diary: “I think Winston Churchill is one of [the] most dangerous men I have ever known.”[31]

Churchill never recorded his own views about King, but likely thought him timid and cowardly, especially after Canada signed up to a mutual defence pact with the United States during Britain’s bleakest hour in the Second World War. But if politics makes strange bedfellows, war makes even odder friends. Near the end of his life, King ultimately confided to his diary: “I felt that perhaps in more respects than one, he was the greatest man of our times.”[32]

Now let’s move to the leafy western edge of Parliament Square. Most of the notable statesmen here belong to the nineteenth century but a few hail from more recent times, including two from South Africa: its leader in the Second World War, Jan Smuts (1870–1950), and its first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela (1918–2013). Canada granted Mandela honorary citizenship in 2001 for his moral leadership and role in bringing about a peaceful end to apartheid in South Africa after serving twenty-seven years in prison.

In a sense this leafy part of London could be called Confederation Corner. That’s because in nearby Victoria Street Sir John A. Macdonald (1815–91) and other Fathers of Confederation met to finalize the British North America Act in 1866. And several of the statesmen portrayed here in Parliament Square played varying roles in Canada’s long road to Confederation.

Trivia: Canada’s Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King often complained Winston Churchill kept him in the dark. On June 6, 1944, an RCMP officer woke King to tell him the invasion of Normandy had begun. The officer had learned about it on the radio.[33]

Let’s start with a statesman who wasn’t even British: President Abraham Lincoln (1809–65) just across the street. Lincoln’s statue is by the noted American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and is a copy of one found in Chicago.

Honest Abe may seem the odd man out among this pantheon of Commonwealth parliamentarians. For Canadians, however, he reminds us of a big reason behind Canada’s Confederation in 1867: the threat of U.S. invasion. At one-million strong, Lincoln’s Union Army emerged from the U.S. Civil War in 1865 as the largest military force in the world. Many believed it might march north right into Canada.

The fear wasn’t unjustified. England relied on the South’s cotton plantations to feed its industrial cotton mills and many of its merchants backed the South. Some in Canada did too. Although Lincoln had no interest in Canada, his secretary of state William Seward did. He believed annexing Canada would be a “double victory” for the Union. His views were even popularized to the tune of “Yankee Doodle”:

Secession first he would put down

Wholly and forever

And afterwards from Britain’s crown

He Canada would sever.[34]

It was a threat Canadians remembered only too well from the War of 1812. Many but not all believed Confederation offered the best chance for survival. “I much doubt whether Confederation will save us from Annexation,” one Father of Confederation confessed. “Even [Sir John A.] Macdonald is rapidly feeling as I do.”[35]

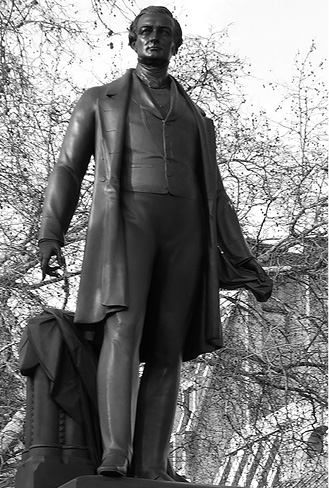

The figure of British prime minister Robert Peel, who abolished the Corn Laws favouring trade with the colonies. He hastened Canada’s economic independence from Britain.

Now let’s look at some of the other political grandees here. At one end is Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850), twice British prime minister in the early 1800s. An old-school Tory, he was nicknamed “Orange Peel” for his anti-Catholic views.

Peel did more to change the economic nature of Canada’s colonial relationship with Britain than any other leader. When he abolished the empire’s preferential trading system, it forced the Canadian colonies to compete against others on a level playing field and in turn helped fan the flames for self-government. It all started with corn.

Peel Monument: Canada and the Price of Corn

What British legislators called “corn” was, in fact, grain: barley, rye, and wheat. As a largely farming society in the 1700s, Britain had dozens of laws to protect grain supplies for citizens and prices for farmers. These were known as “Corn Laws” and gave price advantages to local grain and colonial imports. Yet at various times, the laws proved disastrous. In 1815, for example, consumers rioted in the streets of London over prices and smashed the windows of leading politicians.

By the mid-1800s, there was so much broken glass around London that politicians finally got the message. Britain was becoming industrialized and free trade was the new mantra. Factory owners reasoned competition made bread cheaper and fed more workers. But another impetus was the worst harvest on record and the Irish potato famine. In 1846, Peel repealed the Corn Laws and opened British markets to cheap foreign grains from every country.

For Canada, the repeal of the Corn Laws came as a shock. That’s because Upper Canada and the Maritimes had benefited from the lower duties on their wheat and timber sold to Britain and had invested heavily in canals to transport it there. The repeal of the Corn Laws meant Canada had to compete against the United States and just about everyone else if it wanted to sell its staples in Britain. The result was an economic depression in Canada. When the economy eventually improved, the colonists saw more reason to manage their own affairs.

Colonies do not cease to be colonies because they are independent. — Benjamin Disraeli, 1863

Next along the row are monuments to Benjamin Disraeli (1804–81), 1st Earl Beaconsfield and Edward Smith-Stanley (1799–1869), 14th Earl of Derby. In 1866–67, the two Conservatives led a precarious minority government that came to power when the Whigs were unexpectedly defeated. Derby was prime minister and Disraeli finance minister. They forged ahead with a plan by the Whigs to unite the Canadian provinces mainly to avoid paying to defend them.

Of the two men, Disraeli was the more colourful and flamboyant. He was a political showman who shocked Victorian society by wearing ruffled shirts, velvet trousers, and flashy waistcoats. He was known as a “Big Englander” for his love of empire, but like all politicians could be contradictory at times. He told Lord Derby: “It can never be our pretence or our policy to defend the Canadian frontier against the U.S. … What is the use of these colonial dead weights which we do not govern?”[36]

Lord Derby settled on the name Dominion of Canada. “It is so like Derby,” said his colleague Disraeli. “He lives in a region of perpetual funk.”

Disraeli’s 1883 statue is by the Italian-born sculptor Mario Raggi and depicts the pale leader in his flashy Garter robes and his trademark ringlet hair.

The Earl of Derby, on the other hand, was a dull, Lancashire aristocrat who became Britain’s longest-serving leader of the Conservative Party — twenty-two years — and three times prime minister. He made the reluctant Disraeli Chancellor of the Exchequer or finance minister despite his lack of numerical acumen. “Relax. They give you the figures,” he reassured Disraeli.

The dull Derby influenced Canada in two ways. First, he was the father of Sir Frederick Arthur Stanley (1841–1908), 16th Earl of Derby, who became governor general of Canada and donated a famous trophy to its national game. Second, he gave his blessing to the original if odd name of the new country.

Derby Monument: Call It Derby, Err Dominion Day

After putting the final touches on the British North America Act, the only decision that remained for the Canadian delegates to the London Conference in 1866 was what to call their new country.

The name Canada was pretty much a no brainer, especially compared to the alternatives being proposed like Borealia and Albionoria. The harder part was to get across the idea that Canada would a big player in the world, self-governing but not entirely independent from Britain. Sir John A. Macdonald and some of the other delegates had proposed calling it the “Kingdom of Canada” but this idea ran into problems down the street at the Colonial Office. Officials there said the term was pretentious and premature for such a young nation. Besides, they added, it would “open a monarchical blister on the side of the Americans” who didn’t want a European monarchy on their border.[37] They instructed Macdonald and his gang to go back to the proverbial drawing board.

It was Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley (1818–96), a devout and teetotal member of Parliament from New Brunswick, who suggested the term “Dominion.” He is said to have encountered it while reading his bible: “He shall have dominion also from sea to sea and from the river unto the ends of the earth …” (Psalm 72:8).[38] It was vague, slightly religious, and potentially as unpopular as Tilley’s one-time bid to ban liquor in his province. But the Canadians could agree on nothing better and so settled on the name Dominion of Canada.

“I see no harm in the concession to them of the term ‘Dominion,’” a British official conceded magnanimously, although others thought the term odd — Queen Victoria among them. But Macdonald claimed later that Derby had insisted upon it. “I was not aware of the circumstances but it is so like Derby,” Disraeli later told Macdonald, “a very good fellow, but who lives in a region of perpetual funk.”[39]

At the end of the row is Henry Temple (1784–1865), 3rd Viscount Palmerston. He was an early fitness buff who liked to flex his muscles in more ways than one. As Britain’s secretary of war for twenty years and foreign minister just as long, he was known for strong-arm tactics in defending the British Empire. While not everyone liked his brinkmanship, he did help ensure Canada’s survival during the U.S. Civil War. His statue by Thomas Woolner was erected in 1876.

Trivia: In 1842, Charles Dickens attended the state opening of the Assembly in Halifax. The Governor read the Speech from the Throne, the military band played “God Save the Queen,” and the politicians shouted yeas and nays in the debates. “It was like looking at Westminster from the wrong end of a telescope,” he said.[40]

Parliament Square offers a good vantage point to view the British Houses of Parliament, also known as the Palace of Westminster. So it is here where we will consider the last two discoveries on this walk.

As its name implies, the building began life as a royal residence. The first palace to occupy this site was built in the time of Edward the Confessor (ca.1003–66), a spiritual king closely linked to the foundation of Westminster Abbey. It was a royal residence until King Henry VIII moved his court to the Palace of Whitehall in 1530. Shortly afterward an early form of parliament began to convene here. Like many Commonwealth countries, Canada adopted the “Westminster model” of government. Understanding how this model developed helps explain some of our own odd parliamentary traditions.

Westminster Palace: The Mother of All Parliaments

Chapels like great halls were common features of medieval palaces. Following the dissolution of the monasteries and the eviction of monks by King Henry VIII, his son Edward VI (1537–53; reigned from 1547) turned the empty St. Stephen’s Chapel in the Palace of Westminster into a makeshift council chamber. Although parliaments had existed as early as the 1200s, they never really had a permanent home until 1547.

The chapel was the ideal place for such meetings. Members sat in the choir stalls opposite each other, close enough to hear but far enough apart not to brawl. Just to make sure, an impartial Speaker sat at the altar to impose order. In time, the stalls on the Speaker’s right were occupied by the Government; those on the left the Opposition.

When they were not debating in the chapel, medieval parliamentarians gathered behind the old choir screen where much of Parliament’s real work occurred. This became known as the lobby. After St. Stephen’s chapel was destroyed by fire, a purpose-built debating chamber was completed in 1857 along the same model. Today St. Stephen’s Entrance Hall occupies the old site where Parliament met for centuries.

Maces date back to when heavy clubs were the only way to enforce obedience and eventually became the symbol of royal authority in Parliament. Before every session, a gold mace is placed in front of the Speaker with its crown (or hitting end) facing the government. Even today, no government business can be conducted without it. During the War of 1812, American invaders stole Upper Canada’s first mace, which had to be hastily replaced before the legislature could reconvene. The original mace was only returned in 1934.

Another parliamentary tradition was created in 1642, when King Charles I entered Parliament and demanded the capture of five treasonous MPs. The Speaker refused to cooperate, saying only Parliament could command him to speak. This established the Speaker not only as Parliament’s referee but its official spokesperson, a role that was sometimes hazardous to the occupant’s health. No fewer than nine Speakers met violent deaths in their role, which is why newly elected Speakers in Canada pretend feebly to resist the job despite good pay and lavish perks, including a lakeside estate in Gatineau Park, Quebec.

Like so many historical buildings in London, the Palace of Westminster was badly damaged during the Second World War. It was rebuilt in 1945–50 but not before Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King had Canadian diplomats ship back some of the rubble to build the gothic ruins on his Ottawa estate.[41]

Trivia: The passage in 1982 of the amended British North America Act (now styled the Canadian Constitution) severed Canada’s last tie to Britain’s parliament.

To finish our walk through Whitehall, let’s briefly consider Canada’s single most important piece of legislation to pass Britain’s parliament: the British North America Act of 1867. Although it was a landmark bill to create the first self-governing colony in the British Empire, nobody seemed to notice much.

The House of Commons: A Parish Is Born

On March 8, 1867, a young John A. Macdonald and a handful of Fathers-to-be of Confederation waited expectantly in the visitors’ gallery of the British House of Commons. Below on the floor, the British North America Act reached its third and final reading. Three years of Macdonald’s life had been spent labouring over the terms of Canadian union and now the moment approached. But the birth was unusual. Not because the newborn country wasn’t strong and healthy, but that it came into this world without so much as a whelp.

The passage of Canada’s defining piece of legislation had been lowkey from the start. It was introduced into Parliament by the Colonial Secretary, Henry Herbert (1831–90), 4th Earl of Carnarvon, who was suffering such a bad head cold no one could hear what he had to say. After passing the House of Lords, the bill was given to an unreliable junior minister to navigate through the Commons where it attracted equally little attention. Indeed at one reading, three-quarters of MPs were absent doing other things.

To Macdonald and the other Canadians it was clear British MPs were indifferent to the creation of their new country. It was as if the BNA Act was a private members bill, Macdonald complained, “uniting two or three English parishes.”[42] The moody Alexander Galt (1817–93), another Father of Confederation, expressed even graver concerns. “I am more than ever disappointed at the tone of feeling here as to the colonies,” he told his wife. “I cannot shut my eyes to the fact that they want to get rid of us.”[43]

Turn now and head back to Westminster Bridge Road where our walk ends at the Westminster Tube Station.