VINI & THE ITALIAN BITTERS

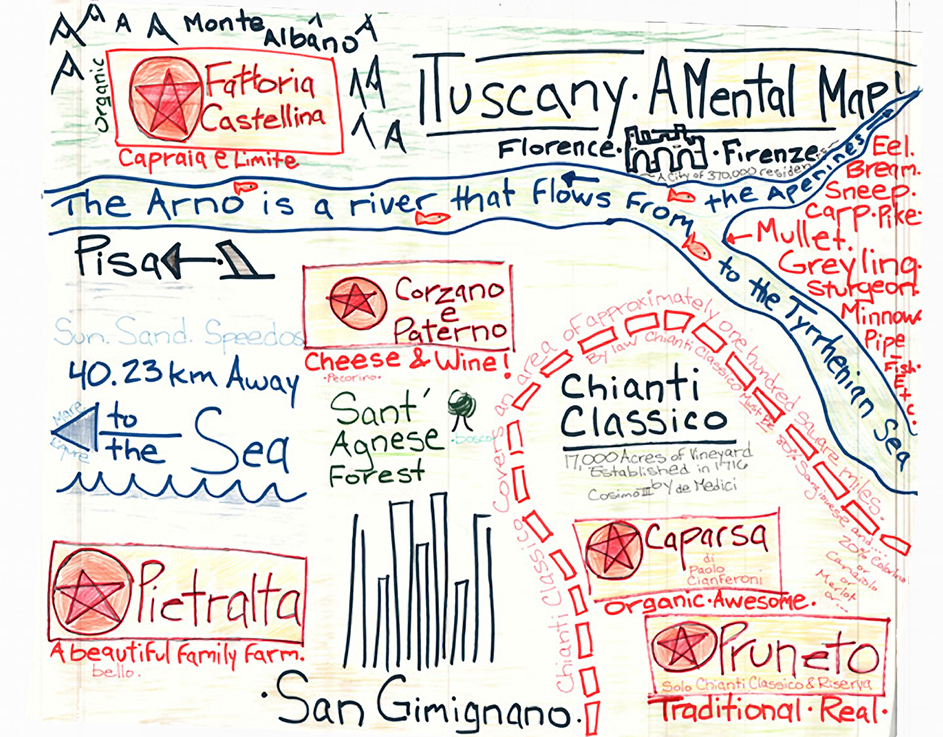

A map drawn by the author to keep his 5-year-old daughter occupied on a long summer day.

My life as a Sangiovese peddler began with a cocktail napkin I found crumpled in the pocket of my jeans, at the end of a trip to Tuscany. On it, in my best tipsy handwriting, I’d written, “Cheap organic Chianti for pizza!” There may have been multiple exclamation points. I’m pretty sure there was lots of underlining in heavy ink. I considered this a truly great idea. It became the credo for what was to become Piedmont Wine Imports.

I don’t think you can learn about a wine—or a person—and their land and food and culture from across an ocean. The wine makers I meet and the conversations we have in fields, on farms, and at tables are my education. Late in the summer of 2011, Ben Davies (my friend and now one of my Piedmont partners) and I went to Europe in search of Sangioveses. For several weeks in Tuscany, we rented a ramshackle 18th-century palazzo near Rufina, minimally maintained by a Florentine academic and his aristocratic partner. The crumbling structure and scattered outbuildings covered a hilltop surrounded by olive trees, but there was no olive oil for us to use on the property! There was wine, though. We did our best to drain the owners’ stockpile of Sangiovese in retribution for the lack of oil.

One cool morning, Ben and I headed out for a run up a rutted dirt road through the vine-covered hills, gasping past churches and Lamborghini tractors, our penance for a exuberantly bacchanalian evening. We must have looked ridiculous to the clusters of American WWOOFers—volunteers in the global WWOOF organic-farm program—and their Albanian overseers deep in legitimate toil during the waning days of harvest. As a stalling tactic while we were catching our breath during a nasty ascent, Ben said, “Tell me, why aren’t we importing this wonderful wine we are drinking every night?” I had no answer besides the fact that I had never imported anything before—but why didn’t we?

That night we heated the kitchen’s ancient bread oven to volcanic temperatures using piles of ripped-up, gnarled old grape vines as fuel. Over wood-fired porcini and Margherita pizzas, Ben convinced me to abandon twelve successful years in the retail wine business, and our little importing company was born. We washed down the terror and excitement of new ideas with bottles of biodynamic Sangiovese from Rufina, a wine that tasted ageless and inextricably part of the land. Sangiovese is the least respected great red wine grape in Italy, probably the world. It is Italy’s most widely planted red grape and is the raw material for many of the country’s greatest wines, including Brunello di Montalcino, Chianti Classico Riserva, and Vino Nobile di Montepulciano. Meticulously farmed Sangiovese resonates. Across central Italy, its ancestral home, it grows with memory-making character. But it is also among the cheapest of wines, sold in bulk to large industrial bottlers. These wines are never allowed to develop. They end up muted—imposters, zombies. Their lifelessness is unsettling, speaking of sick agriculture and mechanized abuse.

The divided identity of Sangiovese is compelling. The grape is not academic or rarified: This is wine for everyone, and has been for centuries. It is a fundamental component of Italian gastronomy. In Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna, it is the base of food traditions, a dominant flavor that has influenced the development of regional cooking—pretty but not frail, with suggestions of red cherry and thorns, herb, bramble, and meat. This multinote aromatic profile and appropriate levels of acidity make Sangiovese comfortable in the company of a wide range of foods. When diligently farmed, decently made, and priced affordably, these are wines for daily drinking with pizzas, pastas, and panini, simply prepared foods that normal people actually eat.

The wine community can veer toward rare and cloistered bottles. I think this is a mistake, because the curiosities they fetishize most people can’t find and don’t drink. I care about wine that matters to people who like good food and wine but have other things going on in their lives and can’t spend vital hours tracking down oddities. In much of Italy, that essential daily wine is Sangiovese, as much a mealtime staple as cheese or pasta. Back home in North Carolina, I always have at minimum a case of solid, basic Chianti in my pantry, between the bottles of olive oil and bags of cannellini beans, ready for my next pizza. For Italians, wine is inextricably connected to food, and it shouldn’t be hard to speak that culinary language using our own larders—American, with a Tuscan accent. A map drawn by the author to keep his 5-year-old daughter occupied on a long summer day.

Jay Murrie founded Piedmont Wine Imports in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. He has travelled the world in search of good wines and here he focuses on a favorite, Sangiovese. He is one of the smartest wine guys we know.

We asked Jay Murrie, Piedment Wine Imports, to tell us a little about the Sangiovese grape and some of his favorite wines. He chose a few from his own collection and some from fellow importers. Here are his thoughts and tasting notes.

CAPARSA, “CAPARSINO”, CHIANTI CLASSICO RISERVA DOCG, RADA IN CHIANTI, TUSCANY, 2008, PIEDMONT WINE IMPORTS

95% Sangiovese. Caparsino is in a league of its own. This certified organic, one-man estate makes compelling wine from old vines in the heart of Chianti Classico, with very little manipulation or modern technology. The richness and acidity of Caparsino are fundamental elements necessary for the wine to age. It’s the best Sangiovese in my cellar. It is a perfect balance of wild aromatics, above average ripeness and archetypal Chianti tannin/acid structure. It’s very close to a perfect wine, and I fail to understand how anyone could not like it. Also certified organic by CCCB. Paolo Cianferoni says he makes this wine in a style “to drink a lot of.” He also suggests serving it with meat and potatoes, and a little olive oil. Where did I put that bistecca alla fiorentina?

FATTORIA CASTELLINA, CHIANTI MONTALBANO DOCG, CAPRIA E LIMITE,

TUSCANY, 2010, PIEDMONT WINE IMPORTS

100% Sangiovese. Fattoria Castellina Chianti Montalbano is certified biodynamic. It is from higher vineyards (250 meters above sea level), closer to the Mediterranean. If Rosso di Caparsa is a wilder take on Chianti Classico, this is Chianti looking at the New World. I love how open and accessible the wine is. Intense, forward, dark berry aromas, some wild herby notes, this is the wine I take to friends who love American Zinfandels and need to be gently led back to Old World wine. The high-toned high-acid thing (that I love) common in Chianti is absent from this red, making it more suited to Korean barbecue than any other Chianti I’ve tried.

FATTORIA CORZANO E PATERNO, “TERRE DO CORZANO” DOCG, SAN PANCRAZIO, CHIANTI, TUSCANY, 2009, PIEDMONT WINE IMPORTS

90% Sangiovese, 10% Canaiolo. Certified organic. This wine has real density of flavor, I feel like I have to unpack layers of earth, smoke, sage/rosemary and then, after some significant aeration, the classic Sangiovese red fruit starts to take over. The wine is so good the next day. I need to remember to age a few bottles for 5 years. They served tagliatelle when we drank Terre di Corzano at the winery in January, and it was a perfect pairing.

FATORRIA CERRETO LIBRI, CHIANTI RUFINA DOCG, PONTASSIEVE, TUSCANY, 2005, LOUIS/DRESSNER

90% Sangiovese, 10% Canaiolo. Is this just a sentimental favorite? We were staying at Cerreto Libri and jogging through their vineyards when Ben Davies convinced me to start a wine-importing business. When we returned to North Carolina, I bought a case of Cerreto Libri. The wine has so much personality! I think this is the kind of wine most people gravitate toward as the years pass. It is not flashy, slick, or squeaky clean, but it’s alive. I like spending time with it. It tastes fully formed, and when I let myself drink what I really want (as opposed to following some wine tangent I may be on), I end up with a bottle of it in my hand.

MONTEVERTINE, “PIAN DEL CIAMPOLO”, ROSSO DI TOSCANO, IGT, RADDA IN CHIANTI, TUSCANY, 2010, NEAL ROSENTHAL

90% Sangiovese, 5% Canaiolo, 5% Colorino. My love for Sangiovese started with Montevertine. In my grad school days Megan (then girlfriend, now wife) and I would scrape together cash to buy a couple bottles of each vintage of the estate’s top wine, “Le Pergole Torte”. It totally redefined Sangiovese for me. For a span of years it was my favorite wine. Eventually, happily, I discovered Pian del Ciampolo, a “little” wine from Montevertine that sits more comfortably on the table at a pizzeria. Pian del Ciampolo is made like an estate’s top wine: harvested by hand, moved in the cellar by gravity (not using pumps) and aged for up to 18 months in big Slovenian barrels before being sold. It is pretty serious: meaty, with plenty of earthy dark fruit to dig into, but you can dig in now, while Le Pergole Torte sits and gathers dust.

MONTESECONDO, ROSSO, SAN CASIANO, TUSCANY, 2010, LOUIS/DRESSNER

95% Sangiovese, 5% Canaiolo. Silvio Messana is universally loved by his Tuscan peers. Every estate owner I visit speaks of him as a kind, articulate leader, a man pointing us toward a better way to make Sangiovese. I can’t believe how fresh it tastes. No leather, just berries—a light, really charming wine.

These days, all sorts of nontraditional Chianti grapes—including Merlot, Cabernet, and other non-indigenous types—as well as barrique treatments, are allowed for DOCG Chianti Classico. Today a wine made just using Sangiovese and Canaiolo grapes grown in Chianti Classico soils and vinified in the method of older Chianti traditions (tank or large Slovenian oak barrels) is deemed “atypical” and is being denied the right to use the Chianti or Chianti Classico name. This is the state of the bureaucracy’s influence on the denominazioni in Italy. The idea of the DOCG’s identity is being reshaped into a new market-based ideal of its “typicity” that has no bearing on the region’s traditions.