Chapter 3

Signs of Something Wrong

After those extraordinary three months in Africa I came back keener than ever to finish university and start a career where I could help people and make a difference. I graduated from La Trobe University with a Bachelor of Occupational Therapy (OT). As an OT my role was to get people who had an injury back to engaging in everyday activities. My first job was as a locum at Caulfield General Medical Centre (CGMC), the same place I was to end up as a patient a few years later.

Em graduates with a Bachelor of Occupational Therapy, La Trobe University 2003.

Right from the start I loved my job. Through university I’d worked in a pharmacy and counted the hours and the dollars. As an OT, I was doing something I was passionate about, so being paid seemed like a bonus.

After Caulfield I began working at the Royal Melbourne Hospital where as a new graduate I was rotated through different areas. I worked in rheumatology, back care, pain management, hand therapy and neurology. In back care the caseload was fairly routine work, mainly WorkCover patients. But in neurology the work was much more varied and interesting. I worked with people in their own homes, for example, helping someone with multiple sclerosis relearn how to shower or a hairdresser who had had a stroke relearn how to cut hair. The gains were obvious and rewarding and I enjoyed the holistic nature of the work, being with people in their own environments. I quickly grew to love this area of OT.

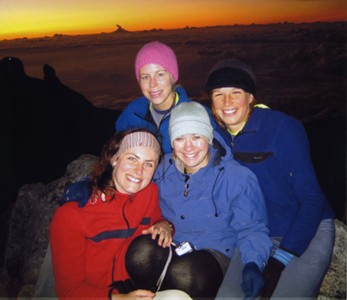

By February 2005, though, I was ready for a holiday. I hadn’t had one since Africa 18 months earlier, and I felt I needed reviving before giving the new job my best shot. I’d just broken up with my long-term boyfriend and was ready for some quality girl time. With three of my closest friends, Al, Fi and Kiri, I set off to spend two weeks in Sabah, Borneo. It was an active holiday; we climbed mountains, snorkelled off the islands, saw the orang-utans and explored the local markets, enjoying the Malay culture and amazing food.

Reaching the peak of Mt Kinabalu, Malaysia at sunrise (Fi, Kiri, Em and Al). This climb in April 2005 precipitated Em’s AVM bleed.

It was in Malaysia that I began to notice some strange changes in my body. Because we were in the tropics we had to take anti-malarials and I had chosen doxycycline, which has a side effect of light sensitivity and nausea. As well as those symptoms I began to experience back pain and found I was a bit clumsy, but I put it down to the the drug and perhaps just being too relaxed on holiday.

The big thing we all wanted to do on this trip was to climb Mt Kinabalu. It was over 4000 metres high but in the Lonely Planet guide they said the climb was easy and that “Grandmas could do it,” so I wasn’t worried. I was fit and I had packed knee tape as a precaution because my knees had suffered in the past as a result of netball. We ascended the mountain in silence, like a human snake. I was ahead the whole way, followed by my friends and rounding us up was our porter Ami. All you could hear were our increasing gasps for air. Step by step. It seemed endless. We were told that as the altitude increased, the foliage would change, but I didn’t expect bodily changes as well.

The plan was to reach the top of the mountain for sunrise. It was pitch dark. We’d walk ten metres and need to stop to catch our breath. Grandmas couldn’t do this! I was struggling and we weren’t anywhere near the top. I had an excruciating, piercing headache and my left side was painfully freezing. I didn’t say anything, partly because I felt paralysed with the pain, but also because I assumed everyone else was feeling the same.

The exhilaration of reaching the top and looking down at the clouds justified the tiredness and pain. Sharing that moment with friends had made the struggle worthwhile. Then of course the exhilaration turned to dread. The saying, “What comes up, must come down,” was true. The human snake reversed, and we set about crab-stepping down the mountain. The novice climbers we passed asked, “How was it?” and we replied, “Fine.” On the way up we’d asked the same question and got the same white lie reply. There was no point in telling them how hard it was. They had to experience it to truly understand.

After the big climb we had three days of sleeping, snorkelling, diving and eating to get over the ordeal, but my body didn’t feel right. I was ultra-sensitive to light, my skin blistering easily, so I decided to go off the doxycycline early. The risk of malaria seemed preferable to these horrible side effects. I was also clumsier than usual but I put that down to being an after effect of the climb. The plane trip home was agony. My neck and back were excruciatingly painful. Unable to sit, I lay on the airport floor and spent the entire flight walking up and down the aisles, while the other girls slept.

The day after my return I started work. In spite of the strange symptoms I’d returned with, I was otherwise brown, rested, refuelled and ready to put lots of energy into my role as a neurological therapist. I didn’t realise that it was my own brain that was about to become the centre of attention.