Why Me? Understanding the Causes of Sexual Addiction

The first question anyone diagnosed with sexual addiction typically asks is pretty much the same: “How did I get this way?” and who could blame them? Ultimately, why a person is sexually addicted is less initially important than “how can I stop,” which is the best place to begin therapy/treatment. Nevertheless, it is helpful to address the topic here, but only after noting the following: knowing why you are a sex addict will not cure or even control your sexual addiction, but it does often provide meaningful shame reduction, and even self-compassion.

Insight vs. Action in the Addiction Healing Process

Nature Versus Nurture

Mark and Thomas, two men now in their mid-twenties, both discovered online porn when they were twelve-year-old best buddies. Both boys were from stable middle-class families in the same neighborhood. Both made good grades, played sports, and were starting to get interested in girls. One day after school Mark’s older brother told them how they could access an online porn site.

Curious and excited by what they might find, the two boys decided to look at porn for a short while before doing their homework.

In the days, months, and years that followed, Mark has occasionally viewed porn for sexual stimulation, but in no way, shape, or form would anyone say he is compulsive or obsessive with his use of pornography. Mostly he just logs on once in a while and quickly masturbates. And when he is dating someone he likes, he doesn’t look at porn at all, preferring to stay focused on the actual woman in his life.

Thomas, on the other hand, after his first exposure to porn at age twelve, went home that very night and turned on the desktop computer in his room—a hand-me-down from his father’s workplace—and cruised different porn sites for over an hour before going to bed. For him, this quickly became a regular pattern. By the time he was fourteen, he was looking at and masturbating to porn at least ten to twelve hours per week, sometimes more. His grades dropped, he isolated, he quit playing sports, and he lost interest in the girls at his school. In short, Thomas got addicted to pornography, and he experienced many of the usual consequences. Today, as an adult, his porn use is completely out of control and ruining his life. He can’t keep a job, he hasn’t dated since high school, he is having issues with erectile dysfunction, and he hates himself.

So why was Mark able to experiment with porn and move forward into a healthy life, when Thomas was addicted from almost the first image?

The simple truth is that some people are inherently vulnerable to addiction, and some people aren’t. Consider alcohol. Nearly everyone tries alcohol at some point in his or her life, but only a small percentage of those folks become alcoholic. The same is true with other potentially addictive drugs and behaviors: many partake, but few become addicted. So why can some people try it and walk away when others cannot? Surely there must be some obvious, easily spotted difference between healthy people and potential addicts? Some telltale sign that’s hard to miss? Right? Wrong.

Consider the example above. Mark and Thomas were so alike they were practically twins. They lived in the same neighborhood, they took the same classes, they earned the same grades, they played the same sports, and they hung out with the same kids. Heck, they even had the same haircut. From outward appearances, there was no way to know that one boy was predisposed to addiction while the other was not.

That said, there is a considerable amount of research into the causes of addiction, with scientists identifying two main categories of risk: nature and nurture.

Nature: Genetics and the Risk for Addiction

Dozens of studies have shown a link between genetic factors and susceptibility to addiction. Most of these studies focus on alcoholism, but it is not unreasonable to extend the findings to other addictions. For starters, various genetic mutations can either directly increase or decrease the risk for addiction, usually by altering the ways in which a particular substance (like alcohol) is experienced and processed in the body and brain.

In one study, scientists found that people who naturally have less reactivity to alcohol (as measured by body sway) are more likely to become alcoholic.1 In other words, people who are genetically less susceptible to the negative side effects of alcohol can consume more longer (get higher) without falling down, getting sick, or passing out, and they are, as a result, more likely to drink alcoholically. Another study links a specific genetic variation affecting D2 dopamine receptors, which are part of the rewards center in the brain, to addiction. This genetic mutation, which essentially magnifies the pleasurable effects of addictive substances and behaviors, increases the risk not just for alcoholism, but for all other types of addiction.2

Genetic variations can also reduce the risk for addiction. For instance, it has long been known that people of East Asian ancestry are much less likely than other groups to become alcoholic. And scientists now know why. In short, they’ve identified a genetic mutation (prevalent in East Asian cultures) that causes a deficiency of the aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme, which is critical to the metabolism of alcohol.3 When alcohol is consumed by people with this genetic mutation, classic hangover symptoms (headache, dehydration, nerve and tissue sensitivity, rapid heartbeat, nausea, and the like) occur almost immediately. In other words, alcohol makes these folks physically ill instead of getting them high. Needless to say, alcoholism is incredibly rare among people with this genetic makeup.

Genetic factors can also contribute to addiction indirectly.4 For instance, genetics are a factor in numerous psychiatric disorders: depression, anxiety, attention deficits, panic disorders, bipolar disorder, social phobia, etc. Not surprisingly, many people living with these disorders choose to self-medicate with alcohol, drugs, and/or intensely pleasurable behaviors. Over time this may become compulsive. In such cases, what is genetically inherited is not a unique response to a potentially addictive substance or behavior, but the propensity for vulnerability to addiction. For instance, people diagnosed with bipolar disorder are much more likely than others to also have a substance use disorder,5 but this increased risk for addiction has nothing whatsoever to do with the ways in which addictive substances and behaviors are experienced in the body. Instead, it’s connected to the person’s desire and/or “need” to escape and dissociate from the shame and emotional pain of an underlying, genetically driven psychiatric disorder.

Other examples of the indirect effect of genetics on addiction are seen when we examine certain heritable personality traits such as impulsivity, risk taking, novelty seeking, and abnormal stress reactivity, all of which significantly increase the risk for addiction.6 In short, the genetic predisposition toward rapid, unplanned actions and/or reactivity without regard to potential negative consequences is closely associated with addiction. Here, it is an inherited tendency toward certain character traits that cause dangerous behaviors, one of which may be the abuse of potentially addictive substances and/or behaviors that leads (indirectly) to addiction. Again, the effects are not related to the physical experience of the addictive substance or behavior; rather, the effects are part of a broad spectrum of psychological and emotional predispositions that incidentally increase the risk for addiction.

7 Wolff, G. L., Kodell, R. L., Moore, S. R., & Cooney, C. A. (1998). Maternal epigenetics and methyl supplements affect agouti gene expression in Avy/a mice. The FASEB Journal, 12(11), 949–957, and, Cooney, C. A., Dave, A. A., & Wolff, G. L. (2002). Maternal methyl supplements in mice affect epigenetic variation and DNA methylation of offspring. The Journal of nutrition, 132(8), 2393S–2400S, among other studies.

Nurture: Environment and the Risk for Addiction

Research tells us that we can’t blame addiction entirely on genetic susceptibility; environmental factors also play a significant role. But how big a role is this, and how can we measure it? One way that scientists have separated nature from nurture in addiction causation studies is by studying the incidence of addiction among adopted children and twins (especially identical twins who were separated at birth and raised by different sets of parents). In this way, the relative influence of genetic risk factors versus environmental risk factors can be measured.

Adoption studies typically ask: what happens to the children of alcoholics if they’re adopted into a family where neither parent abuses alcohol? Researchers have consistently found that people with biological, (not adoptive) parents who were alcoholics are much more likely to develop alcoholism.8 So score a point for genetics. Of course, being more likely to develop alcoholism doesn’t mean that alcoholism is an absolute certainty. In fact, lots of people in these studies were not alcoholic. Plus, plenty of biological children of non-alcoholics do become alcoholic. So now we can score a few points for environmental influences.

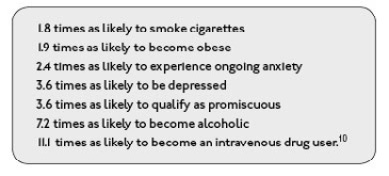

Comparable studies have been conducted for cocaine, nicotine, and opiates with remarkably similar results,9 leading scientists to conclude that somewhere between 40 and 70 percent of the risk for addiction is genetic, and somewhere between 60 and 30 percent is environmental. If we wanted to use the center point of those estimates, we could say that the risk for addiction is 55 percent genetic and 45 percent environmental. In addition to this relatively even distribution of blame, it appears that nature can easily be usurped by nurture (again potentially epigenetics). For instance, abused and/or neglected children have an incredibly high risk for addiction (and other adult-life psychological issues) regardless of genetic influences. Furthermore, the more times a child is traumatized, the greater the likelihood of adverse reactions, such as addiction, later in life. One study found that survivors of chronic childhood trauma (four or more significant trauma experiences prior to age eighteen) are:

10 Anda, R., Felitti, V., Bremner, J., Walker, J., Whitfield, C., Perry, B., . . . Giles, W. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3):174–186.

Another relatively common environmental risk factor is early exposure to an addictive substance or behavior. Numerous studies have found that the lower the age of first use, the higher the likelihood of addiction.11 This is true with all forms of addiction, including sexual addiction. Whether sex was vilified or glorified, a large percentage of sex addicts were exposed to it at an unusually early age.12 One recent survey of adult sex addicts found that 41 percent were using pornography before the age of twelve.13 Keep in mind the fact that when today’s adult sex addicts were twelve or younger, Internet porn was not nearly as accessible as it is today, so kids had to look hard for it, or, more likely, they had to be inadvertently or intentionally exposed to it—a potentially traumatic experience either way. (Nowadays the average age of first exposure to pornography is eleven.14 Yikes! More about teens and sexual addiction in our online bonus book resource section, which can be downloaded at hcibooks.com.)

Sometimes the age of first use (drugs or behaviors) and familial instability (including a family history of mental illness and/or addiction) are directly related, as addictive substances and/or activities are readily available within the home. In such cases, the other environmental risk factors (abuse, neglect, inconsistent parenting, etc.) may be the overarching factor in the development of addiction.

Trauma and Addiction

There is an undeniable link between childhood trauma and numerous adult-life symptoms and disorders, including addiction.

My esteemed colleague, Dr. Christine Courtois, provides a brief definition of trauma in her new book, It’s Not You, It’s What Happened to You, writing, “Trauma is any event or experience (including witnessing) that is physically and/or psychologically overwhelming to the exposed individual.”15 Dr. Courtois also notes that trauma is highly subjective. In other words, incidents that might be highly traumatizing to one person may be humdrum for another.16 For instance, a fender-bender might be much more traumatic for a new mother with her baby in the car than say for a professional race car driver.

There are many types of trauma as can be seen below:

Impersonal trauma: acts of God such as natural disasters, being in the wrong place at the wrong time, etc.

Interpersonal trauma: intentional acts by other people, such as abuse, neglect, inappropriate enmeshment, assault, robbery, etc.

Identity trauma: based on the victim’s inherent characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.

Community trauma: based on the victim’s membership in a particular community, such as a family, tribe, religion, etc.17

Sadly, for many people the experience of trauma is chronic, that is—repeated and layered over time. This is often referred to as complex trauma. Complex trauma is especially problematic when it occurs within early family life, which is an interpersonal trauma subtype known as attachment trauma. Complex (chronic) attachment trauma is highly postively correlated with addictions of all types, but shows up with high frequency particularly among sex and love addicts.

Denise, a twenty-five-year-old market analyst, grew up the only daughter of two alcoholics. Her father sexually abused her from a very young age, and her mother abused her verbally, emotionally, and sometimes physically. The abuse was always worse when they drank. Now, as an adult, Denise is struggling to hold on to a job, to maintain her friendships, and to control her sexual behavior. She says that every evening after work she logs on to half a dozen or so hookup apps and chats with men seeking sex. More often than not, she has sex with two or three different men by the end of a given night. As soon as one man leaves her apartment, she’s online looking for the next one. Most nights she is awake and acting out sexually until three or four in the morning, leaving her both tired and unproductive the next day at work, which is an issue that may soon get her fired. Deeply ashamed of her behavior, she nevertheless continues to engage in it, stating that it’s the only thing that makes her feel important and alive. At this point, she’s at a loss to explain her actions. She has no way of knowing or understanding that her compulsive adult sexual responses to any and all forms of emotional discomfort are in fact learned coping mechanisms that are relatively normal (or at least expected) given the degree and nature of the complex attachment trauma she experienced in childhood. Without this understanding, she simply sees herself as dirty, unworthy of love, and hopelessly broken.

Sadly, without some form of therapy or intervention, individuals like Denise often don’t make the connection between their childhood trauma and their adult-life sexual problems. Due to this lack of understanding and association, many of these folks think of themselves as “broken” or simply as “bad people,” using their adult-life sexual acting out as proof of how unlovable they really are. They simply don’t understand that their upbringing was lacking and left them without a positive sense of self or needed life skills, and that their problematic sexual behaviors are an adaptive response to what they experienced.

The simple truth is addicts of all types typically report multiple instances and forms of early-life neglect, abuse, shame, and family dysfunction.18 In one survey asking sex addicts about their childhoods, 97 percent reported emotional abuse, 83 percent reported sexual abuse, and 71 percent reported physical abuse.19 In another survey, 38 percent reported emotional abuse, 17 percent reported sexual abuse, and 16 percent reported physical abuse.20 Obviously, that’s a wide variance between studies. Numerous factors may account for the variation in findings, and most likely the real numbers lie somewhere in the middle. Either way, it is clear that an abnormally large percentage of sex addicts were traumatized in childhood.

Put simply, addicts nearly universally report early-life complex attachment trauma: neglect, abuse, inconsistent parenting, and/or other forms of family dysfunction.21 Basically, their developmental and dependency needs are not met in childhood they walk around their world feeling like they have a “hole in their soul,” as one addict put it. So we see that addicts are most often people who’ve been emotionally wounded, usually early and repeatedly, in ways that leave them feeling unworthy of love, affection, connection, and happiness. They end up with a distorted, deeply shame-based sense of self, where every negative or problematic experience serves as a reminder that they, themselves are defective and unlovable. And when that’s the message bouncing around in a person’s head, it’s understandable that he or she might consistently and repeatedly choose to self-medicate and/or self-soothe with drugs, alcohol, and/or a pleasurable behaviors, in time becoming emotionally and psychologically dependent on these temporary (feel good) external fixes.

Sexual Abuse, Sexual Shame,

and Sexual Addiction

Without doubt, childhood sexual abuse, whether a single incident or chronic, leaves its victims with feelings of both confusion and shame. This is true whether the abuse is overt, meaning “hands-on,” or covert, as occurs when a parent “emotionally partners” with a child (see the next section for further information).22 Exacerbating matters is the fact that childhood sexual abuse is often coupled with other forms of early-life trauma, such as emotional, psychological, and/or physical neglect and abuse,23 creating layers of traumatic experience and various forms of shame—though sexual shame is nearly always the most powerful.

Oftentimes sexually shamed children begin to self-medicate their emotional discomfort relatively early in life, usually during adolescence but sometimes even before. After all, body image issues, shame about being looked at and/or touched inappropriately, and feeling “icky” about too much trust and affection can all begin very early in childhood. It is is typical to see these emotionally challenged children seeking solace (by early adolescence), via drug and alcohol abuse. That said, many children also learn (or are taught) that they can self-soothe with sexual behaviors (including sexual fantasy and masturbation), usually by eroticizing and reenacting some aspect of their sexual trauma. In fact, self-soothing through eroticized reenactment of trauma is relatively common.24

Unfortunately, though distracting in the moment, these self-soothing sexual behaviors tend to exacerbate preexisting shame and emotional discomfort, thus creating an even greater need for escape and dissociation. As such, many deeply sexually shamed “sexual trauma survivors” find themselves mired in an addictive cycle of self-hatred and sexual shame, ameliorated by sexual fantasy and activity, followed by still more self-hatred and sexual shame. In short, their escapist addictive sexual fantasies and behaviors automatically and inherently trigger the need for more of the same. This, as you may recall from Chapter 1, is the basis of the sex-addiction cycle.

Understanding Covert Incest

Covert incest, also known as emotional incest is the indirect, sexualized and/or romanticized emotional use/abuse of a child by a parent, stepparent, or any other long-term caregiver.25 In contrast to overt sexual abuse, which involves hands-on sexual contact, covert abuse involves less direct forms of sexuality—sexuality that is emotionally implied or suggested rather than overtly acted out. In this way, a child is used for parental emotional fulfillment, forced to support the adult by serving as a trusted confidante and/or an “emotional spouse.” Though there may be little to no direct sexual activity, these overly enmeshed relationships have a sexualized undertone, with the parent expressing overly graphic verbal interest in the child’s physical development and sexual characteristics and/or betraying the child’s boundaries through voyeurism, exhibitionism, sexualized conversations, and inappropriate sharing of intimate stories and/or images.

Covert incest often occurs when parents have distanced themselves from one another both physically and emotionally, and one or the other parent begins to place their adult emotional needs on their child, using the child as a kind of surrogate partner. Some parents may tie their own self-esteem to the academic, sports or other success by the child. Either way, the child’s developmental needs tend to be ignored, and emotional growth (especially in the area of healthy sexual and romantic attachment) can be profoundly stunted. Often, the perpetrating adult is usually completely unaware of the emotional damage he or she is creating by using their child as an emotional object, rather than turning to other adults for support. And typically for many trauma survivors without concrete, identifiable trauma stories (involving: hitting, rape, profound neglect, violence etc.), this kind of emotional damage can be hard to identify. Clients in treatment will say things like, “Once Dad left, I got all of Mom’s attention, she was with me constantly and told me everything.” They often feel like they got a pretty good deal, but in reality being responsible for a parent’s emotional needs at such a young age can be very damaging to a child and bodes poorly for their future relationships and sexuality.

Dashiell, a thirty-three-year-old CPA raised in an upper-middle class household, says that for many years, before his much younger sister was born, his mom would pull him out of school some days, simply because she wanted his company. She just dragged him along while she shopped, and then they’d have lunch, with Dash listening to his mom talk about her life with his dad and how she felt about that relationship. Sometimes she would take Dash to the movies with her—not kid movies, but grown-up stuff. He says that his dad was always either working or drinking, and his mom didn’t have many women friends, so he was her fill-in. “In a way, it wasn’t so bad. I liked skipping school and eating out and getting to see movies that other kids didn’t, but at the same time I always felt a bit weird with her. She always seemed to sit a little too close to me, and she commented on my body all the time, especially when I was a teenager. And sometimes she’d walk into the bathroom when I was in the shower to put away towels or some stupid thing that could easily have waited until I was done and dressed. Lots of stuff like that. I had no privacy. Even if I was in my room with the door locked she would be right outside, listening and asking me through the closed door what I was doing, was I okay, did I need her for anything. All I really wanted was for her to leave me alone. Sometimes she would undress in front of me asking me to help “choose her outfit” while walking around half naked. What I find confusing even now, is that she never actually touched me sexually. Still, by the time I was fifteen or sixteen, just being in the same room with her made my skin crawl.” Now in his early thirties, Dash is struggling with sexual addiction, compulsively hooking up with women via apps like Tinder and Ashley Madison, at all hours of the day and night. His relationship with his mother, feeling out of control, set the template for future sexual intimacy as having to take place where he does feel a sense of control (emotional safety)—with prostitutes or casual affairs.

The mixed feelings Dash has about adult intimacy are not uncommon in covert incest survivors. On the one hand, his special relationship with his mother was a cherished privilege; on the other hand, something about it felt icky and wrong. Most covert incest survivors initially resist the notion that they have been sexually abused because they were never actually touched in a sexual way by the perpetrator. However, these relationships are indeed sexualized. Essentially, a child in these circumstances is sexualized and treated as an adult partner, and therefore he or she is deprived of healthy attachment bonds, stable emotional growth, and many other basics of childhood development. In lieu of healthy development, the child is taught that his or her value is based not on who he or she is as a person, but on how much he or she can please, amuse, and/or bond with the caretaker. As a result, covert incest survivors typically respond in the same ways as survivors of overt (hands-on) sexual abuse, with many of the following adult-life symptoms and consequences:

√ Characterlogical and personality (ego) problems

√ Addiction and/or compulsivity

√ Difficulty developing and maintaining long-term intimacy

√ Narcissism and angry emotional reactivity

√ Shame and feelings of inadequacy

√ Dissociation

√ Difficulties with self-care (emotional and/or physical)

√ Love/hate relationships, especially with spouses and family

√ Inappropriate bonding or overly distancing with their own child (intergenerational abuse)

√ Adult intimacy disorders

As pervasive and damaging as covert incest is, it frequently goes unrecognized even in treatment therapy settings. As my colleague Debra Kaplan puts it, “The obvious signs are obscured from plain view. It is like the air in the room—it’s here, but you can’t see it.”26 This confusion affects survivors and therapists alike. In general, the thinking seems to be that if there’s no actual physical sexual contact, then no harm has been done. It is only when we dig beneath the surface that we see the connections between covertly incestuous behaviors and adult intimacy and addiction issues, including sexual addiction.

Sexual Addiction: The Perfect Storm

Sex addicts, like all other addicts, are subject to a combination of genetic and environmental risk factors. For instance, a combination of genetic predisposition, abusive, alcoholic, or mentally ill parents, childhood trauma, and early exposure occurs relatively often, creating a witch’s brew of ongoing life problems: not just addiction, but numerous other social, emotional, and psychological issues. Given this, it is clear that any discussion about the possible causes of sexual addiction is not so much an argument of nature versus nurture as an examination of how the two factors come together to influence individual behavior and response. In short, addictive disorders of all types, sexual addiction included, are driven by genetics and environmental factors. When early-life sexual trauma (overt or covert) is part of the mix, the odds of sexual addiction versus another addiction are greatly increased.