6. Reminders of Moses’ Lowly Origins (6:9–7:5)

9Moses reported this to the Israelites, but they did not listen to him because of their discouragement and cruel bondage.

10Then the LORD said to Moses, 11“Go, tell Pharaoh king of Egypt to let the Israelites go out of his country.”

12But Moses said to the LORD, “If the Israelites will not listen to me, why would Pharaoh listen to me, since I speak with faltering lips?”

13Now the LORD spoke to Moses and Aaron about the Israelites and Pharaoh king of Egypt, and he commanded them to bring the Israelites out of Egypt.

14These were the heads of their families:

The sons of Reuben the firstborn son of Israel were Hanoch and Pallu, Hezron and Carmi. These were the clans of Reuben.

15The sons of Simeon were Jemuel, Jamin, Ohad, Jakin, Zohar and Shaul the son of a Canaanite woman. These were the clans of Simeon.

16These were the names of the sons of Levi according to their records: Gershon, Kohath and Merari. Levi lived 137 years.

17The sons of Gershon, by clans, were Libni and Shimei.

18The sons of Kohath were Amram, Izhar, Hebron and Uzziel. Kohath lived 133 years.

19The sons of Merari were Mahli and Mushi.

These were the clans of Levi according to their records.

20Amram married his father’s sister Jochebed, who bore him Aaron and Moses. Amram lived 137 years.

21The sons of Izhar were Korah, Nepheg and Zicri.

22The sons of Uzziel were Mishael, Elzaphan and Sithri.

23Aaron married Elisheba, daughter of Amminadab and sister of Nahshon, and she bore him Nadab and Abihu, Eleazar and Ithamar.

24The sons of Korah were Assir, Elkanah and Abiasaph. These were the Korahite clans.

25Eleazar son of Aaron married one of the daughters of Putiel, and she bore him Phinehas.

These were the heads of the Levite families, clan by clan.

26It was this same Aaron and Moses to whom the LORD said, “Bring the Israelites out of Egypt by their divisions.” 27They were the ones who spoke to Pharaoh king of Egypt about bringing the Israelites out of Egypt. It was the same Moses and Aaron.

28Now when the LORD spoke to Moses in Egypt, 29he said to him, “I am the LORD. Tell Pharaoh king of Egypt everything I tell you.”

30But Moses said to the LORD, “Since I speak with faltering lips, why would Pharaoh listen to me?”

7:1Then the LORD said to Moses, “See, I have made you like God to Pharaoh, and your brother Aaron will be your prophet. 2You are to say everything I command you, and your brother Aaron is to tell Pharaoh to let the Israelites go out of his country. 3But I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, and though I multiply my miraculous signs and wonders in Egypt, 4he will not listen to you. Then I will lay my hand on Egypt and with mighty acts of judgment I will bring out my divisions, my people the Israelites. 5And the Egyptians will know that I am the LORD when I stretch out my hand against Egypt and bring the Israelites out of it.”

9–12 In spite of the grandeur of what “I am the LORD” means for Israel in the current situation, the people do not listen “for shortness of breath” (miqqōṣer rûaḥ). The NIV weakly translates “their discouragement” (v.9); but it is the inward pressure caused by deep anguish that prevents proper breathing—like children sobbing and gasping for their breath.

This makes such an impact on Moses that he has another attack of self-distrust and despondency. How can he persuade Pharaoh when he has failed so miserably to impress his own countrymen, who presumably have a naturally deep interest in what he has to say, given their circumstances (vv.11–12a)? Anyway, his lips are “faltering” (v.12b; NIV mg., “uncircumcised”) for the job they have been given to do (cf. the “uncircumcised” ears of Jer 6:10; “uncircumcised” heart of Jer 9:26). Thus Moses has returned to his fourth objection as stated in 4:10. He is not worried about his ability to speak fluent Hebrew after such a long time away from Eygpt, nor is he claiming to have a speech impediment. He is only skeptical of his ability to be persuasive in influencing Pharaoh by means of his oratorical skills.

13–30 Many regard this section as an “interruption” of the narrative. But the narrative itself is at a turning point. The stage has been set in 1:1–6:12, and now the main action begins. However, before that action begins, it is important that the author once again remind his readers just who Aaron and Moses are, “to whom the LORD” has spoken (v.26). In fact, the whole genealogy of vv.14–25 is surrounded and framed by the near verbatim repetition of vv.10–13 in vv.26–30 and v.14a in v.25b. This genealogical list concentrates on the two men and how they happen to be at this precise and momentous juncture in the history of humankind and nations.

Everything in the list suggests that God’s choosing of Moses has nothing to do with natural advantage or ability. The list stops after naming only three of Jacob’s sons—Reuben, Simeon, and Levi—for its object has been reached. Moses and Aaron spring not from the “firstborn,” Reuben, but from Levi, Jacob’s third son—and not even then from Levi’s oldest son but from Kohath, his second son (vv.16–19). And Moses himself is not the oldest son of his father, for Aaron is older. Moses’ calling and election by God are gifts of grace not based on rights and privileges of birth.

Nor is Moses’ pedigree all that noble from a moral standpoint, for the mere mention of each of these three names is enough to remind contemporaries of an “informing theology” that rattles ethical skeletons in his past—Reuben committed incest with his father’s concubine (Ge 35:22), while Simeon and Levi were guilty of unwarranted outrage against Shechem (34:25–31). So wicked were the three older sons of Jacob that they each inherited a curse: Reuben lost his birthright as “firstborn” (Ge 49:3–4), and Simeon and Levi were denied an inheritance with the tribes and were scattered among them instead (49:5–8).

But this is not done in any fatalistic way; for while Reuben’s and Simeon’s descendants do morally follow in their fathers’ footsteps, Levi’s descendants, with devotion to God, turn what was a curse into a blessing and use their dispersion throughout the tribes as an avenue of blessing to all through the priesthood and service at the sanctuary of God.

This honor did not prevent Levi’s descendant Korah (vv.21–24) from destroying himself by his own rebellion (Nu 16); yet his descendants were not thereby forever adversely determined for evil, for they later rose to a place of high position in leading Israel in songs of praise in the temple and in composing Psalms 42–49, 84–85, and 87. So the making of “this same Moses and Aaron” and the uses they are put to after they were made are totally the work of God. There is nothing left for them to claim or boast about in their pedigree. Nevertheless, the record also makes plain that there is a congruity between the experiences and all the endowments that have accrued to Moses during these eighty years of life; thus election works in the natural realm as well as the spiritual.

The text repeats the words of vv.10–13 in vv.26–30 as though to say, “Look who is talking back to God! A man of few credentials except those given him in the providence and grace of God!” But never mind that, v.28 seems to affirm; it is now a whole new game. The style of the Hebrew grammar (see Notes) declares, “I am the LORD.” The hour has come, and the name of Yahweh will be all the equipment Moses needs.

7:1–5 The theme here is similar to the point made in 3:18–22. While Yahweh has made Moses as “God” to Aaron and Aaron in turn as his “prophet” to the people, Moses has also been “ordained, appointed” (nātan) as “God” to Pharaoh in that he will speak and act with authority and power from above as God’s representative. Aaron will be Moses’ “prophet” addressing Pharaoh (v.1; cf. 4:15–16). Moses, then, will be the source of the divine oracles from above, and Aaron is to be God’s mouthpiece. Few texts give us a better view of just what it means to be a prophet for God.

But again this team is warned that Pharaoh’s heart will be “hardened” (qāšâ [GK 7996], v.3; see on 4:21), even though God will graciously provide him with supporting evidence by way of signs and wonders. The announcement from God will be the occasion but not the cause of Pharaoh’s actions. Nevertheless, after God has judged Egypt with his “mighty acts of judgment” (v.4; see Notes on 6:6), Israel will come out by its “divisions” (see Notes on 6:26).

Not only will Israel know what is meant by the name Yahweh, but so will the Egyptians. It will be as Jeremiah 16:21 described what it was to know “the LORD”: “Then they will know that my name is the LORD.” In addition to understanding the significance of the tetragrammaton (yhwh), these miracles will also be an invitation for the Egyptians to personally believe in this Lord. Thus the invitation is pressed repeatedly in 7:5; 8:10, 22; 9:14, 16, 29; 14:4, 18—and some apparently do believe, for “a mixed multitude” (12:38, KJV) leaves Egypt with Israel.

NOTES

13 Whether this verse is a summary of chs. 3–5 (Rawlinson, 1:155) or an anticipation of Aaron’s active involvement in 7:1–5 is debatable, but it seems best to understand it as a renewal of the orders received at the burning bush just as a new start begins in 7:1.

14 ![]() (rā ʾšê bēt-ʾabōtām, “heads of their families”) is literally “heads of their father’s houses” (cf. Ge 12:1; 20:13; Ex 1:1; Nu 1:4). The word “house” came to mean “household” and thus “family.” The list for Reuben’s sons is identical to Genesis 46:9 and 1 Chronicles 5:3.

(rā ʾšê bēt-ʾabōtām, “heads of their families”) is literally “heads of their father’s houses” (cf. Ge 12:1; 20:13; Ex 1:1; Nu 1:4). The word “house” came to mean “household” and thus “family.” The list for Reuben’s sons is identical to Genesis 46:9 and 1 Chronicles 5:3.

15 The list for the sons of Simeon is the same as Genesis 46:10, but it differs from Numbers 26:12 and 1 Chronicles 4:24. In the later two lists Jemuel is Nemuel, Zohar is Zerah, and Ohad is missing, perhaps because he subsequently died or because of some other unknown reason. In 1 Chronicles 4:24 Jakin appears as Jarib.

20 The “Amram” mentioned here is probably not the “man of the house of Levi” in 2:1, except in a removed sense (see comment on 2:1). The verb ![]() (wattēled, “and she bore”) can be used of an ancestor removed by several generations as “bearing” great-grandchildren, even as Jacob’s two wives also “bore” the children their handmaids gave to Jacob (Ge 46:18, Ge 46:25).

(wattēled, “and she bore”) can be used of an ancestor removed by several generations as “bearing” great-grandchildren, even as Jacob’s two wives also “bore” the children their handmaids gave to Jacob (Ge 46:18, Ge 46:25).

26; 7:4 The term ![]() (ṣebā ʾôt, “divisions” or “armies”) has not previously been used of the people of Israel. Later this term with the name of Yahweh will become one of the most frequent names for God: “LORD of hosts” (NIV, “LORD Almighty”), e.g., as David was reassured as he went to meet Goliath in 1 Samuel 17:45.

(ṣebā ʾôt, “divisions” or “armies”) has not previously been used of the people of Israel. Later this term with the name of Yahweh will become one of the most frequent names for God: “LORD of hosts” (NIV, “LORD Almighty”), e.g., as David was reassured as he went to meet Goliath in 1 Samuel 17:45.

28 ![]() (wayehî beyôm dibber, “Now when the Lord spoke”) is literally, “And it came to pass in the day of [Yahweh’s] speaking [to Moses].” The unusual Hebrew grammatical form has the noun “day” in the construct with the verb “he spoke” (cf. Ge 2:3; Hos 1:2 et al.). This construction highlights the fact that a new day has dawned.

(wayehî beyôm dibber, “Now when the Lord spoke”) is literally, “And it came to pass in the day of [Yahweh’s] speaking [to Moses].” The unusual Hebrew grammatical form has the noun “day” in the construct with the verb “he spoke” (cf. Ge 2:3; Hos 1:2 et al.). This construction highlights the fact that a new day has dawned.

D. Judgment and Salvation through the Plagues (7:6–11:10)

OVERVIEW

The plague account exhibits a clear and unified structure. Its unitary character has long been noticed, especially by Isaac Abravanel (1437–1508), Rabbi Samuel ben Meir (d. 1158), and Bahya ben Asher in his thirteenth-century commentary (see Ziony Zevit, “The Priestly Redaction and Interpretation of the Plague Narrative in Exodus,” JQR 66 [1976]: 194, nn. 6–7).

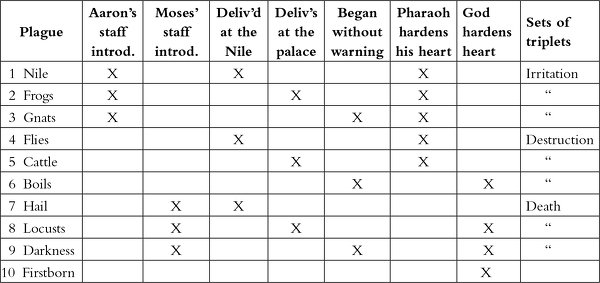

The first nine plagues are arranged in three groups of three plagues each. The first plague in each group (viz., nos. 1, 4, 7) is introduced by a warning delivered to Pharaoh early in the morning as he goes out to the Nile (7:15; 8:20; 9:13 [though this last one does not specify the Nile]). The second plague in each group (nos. 2, 5, 8) is also introduced by a warning, but it is delivered to Pharaoh at his palace (8:1; 9:1; 10:1). The last plague in each group (nos. 3, 6, 9) begins without any warning (8:16; 9:8; 10:21).

When these same nine plagues are considered sequentially, however, they may be viewed in another arrangement of three sets of triplets in an ascending order of severity: the first three (nos. 1, 2, 3) introduce irritations, the second set (nos. 4, 5, 6) destructions, and the final set (nos. 7, 8, 9) death. Again, each plague in the first set is brought on with the use of Aaron’s staff (7:19; 8:5, 16); the first two plagues in the second set (nos. 4, 5) are the work of the Lord directly, while the last one (no. 6) is the result of Moses’ word (8:24; 9:3, 6 and 10); and the last set of three (nos. 7, 8, 9) are all brought on by Moses with his outstretched hand and staff (9:22–23; 10:12–13, 21–22).

Other attempts to find the structure and meaning of the plagues are less convincing. Cassuto, 92–93, suggests that all ten plagues be broken down sequentially into sets of two according to the nature of the things affected: the Nile (nos. 1, 2); then two similar plagues (lice and flies; nos. 3, 4); animals and humans are next affected (nos. 5, 6); then crops are damaged (nos. 7, 8); then darkness of days and darkness of death (nos. 9, 10). There is insufficient evidence from the text to justify this arrangement, and the logic is missing in some (nos. 3, 4) or is forced in others (nos. 9, 10).

Dennis McCarthy (“Moses’ Dealings With Pharaoh,” CBQ 27 [1965]: 341–43) finds a concentric scheme that begins with the miracle of the staff turned into a snake numbered first and that continues through the nine plagues by dividing the miracle and nine plagues into two groups of five, so that the second set of five is matched with the first set in such a way that episode one is paired off with episode ten, two with nine, and so forth. But this chiastic arrangement is highly selective and artificial. Admittedly, it is dependent on certain key phrases and on the observation of the alternation of long and short units, but it neglects to account for some of these same key phrases in other units and includes the snake-staff miracle as number one. Most damaging is its failure to account for the real purpose and aim of these plagues.

Only the triplet grouping brings out the aim of the plagues and their sequence as recorded here. The initial plague in each triplet (nos. 1, 4, 7) has a purpose clause in which God sets forth for Moses his rationale and aim in bringing the hardships in that set:

- The first set (7:17): “By this you [Pharaoh] will know that I am the LORD” (repeated in 8:10 and in effect in 8:19), meaning that Pharaoh will come to know just who Yahweh is and what the dynamic presence of his name signifies.

- The second set (8:22): “That you will know that I, the LORD, am in this land,” meaning God’s overseeing providence and guidance of the world.

- The third set (9:14): “So you may know that there is no one like me in all the earth,” meaning that the scope and force of God’s power (cf. 9:16, 29–30; 10:1) are beyond anything known to humankind in all the earth (see Labuschagne, 74–75, 92–94). In fact, this overall purpose for the plagues is already announced in 7:4–5.

This display of “power” and “signs” pointing to God’s person are also part of the psalmist’s appeal to these plagues in Psalms 78:42–51 and 105:28–38.

1. Presenting the Signs of Divine Authority (7:6–13)

6Moses and Aaron did just as the LORD commanded them. 7Moses was eighty years old and Aaron eighty-three when they spoke to Pharaoh.

8The LORD said to Moses and Aaron, 9“When Pharaoh says to you, ‘Perform a miracle,’ then say to Aaron, ‘Take your staff and throw it down before Pharaoh,’ and it will become a snake.”

10So Moses and Aaron went to Pharaoh and did just as the LORD commanded. Aaron threw his staff down in front of Pharaoh and his officials, and it became a snake. 11Pharaoh then summoned wise men and sorcerers, and the Egyptian magicians also did the same things by their secret arts: 12Each one threw down his staff and it became a snake. But Aaron’s staff swallowed up their staffs. 13Yet Pharaoh’s heart became hard and he would not listen to them, just as the LORD had said.

COMMENTARY

6–9 After eighty years of preparation Moses begins his life’s work (v.6): “Moses and Aaron did just what the LORD commanded them.” It is only fair for Moses to record his faithfulness to God’s command just as he frankly records his failures to obey God’s commands. He and Aaron must reappear before Pharaoh, who in turn will ask them to perform a miracle, presumably to assure him that they are messengers of Israel’s God (vv.7–9). Undoubtedly his tone is supercilious and he expects there will be no miracle, for he must have judged Moses and Aaron to be nothing but opportunists and insurrectionists. Pharaoh’s literal words are: “Give a miracle for yourselves” (v 9), as though it were more important that it be done for the sake of Moses and Aaron than for Pharaoh.

Significantly, Scripture judges Pharaoh’s demand for validation of such claims as reasonable even if given with the wrong attitude. The Lord informs Moses to use the first of the three signs he used to convince Israel that he is indeed an accredited messenger of God (v.9; see 4:2–9, 30–31). However, in this instance Aaron’s staff (it is the same as Moses’ staff or the staff of God; cf. 4:17; 7:15, 17, 19–20) when cast down becomes a tannîn (“great serpent, dragon, crocodile”; see Notes; in 4:3–4 it became a nāhāš, “snake.”) The connection of tannîn with the symbol of Egypt is clear from Psalm 74:13 and Ezekiel 29:3.

10–13 Moses and Aaron do exactly as God instructs them—only to learn that Pharaoh’s wise men, sorcerers, and magicians (see Notes) are able to imitate the same feat by their magical arts (vv.10–11; see Notes). The use of magic in Egypt is well documented in the Westcar Papyrus, in which magicians are credited with changing wax crocodiles into real ones only to be turned back to wax again after seizing their tails. Montet (92–94, fig. 17) also refers to several Egyptian scarabs that depict a snake charmer holding a serpent made stiff as a staff up in the air before some observing deities (cf. ANET, 326, with a spell on a “spotted” knife [representing a snake?] that “goes forth against its like” and devours it).

The relationship between Aaron’s miracle and the magical act of the magicians (whom Paul calls Jannes and Jambres in 2Ti 3:8) is hard to define. Possibly by illusion and deceptive appearances they are able to cast spells over what appear to be their staffs but which are actually serpents rendered immobile (catalepsy) by pressure on the nape of their necks and by the use of magical spells. Or perhaps it is done via demonic power. (For a fuller treatment of this difficult subject, see Keil and Delitzsch, 1:475–77.) However, as evidence of God’s greater power, Pharaoh’s magicians lose their “staffs” when Aaron’s staff “swallows up” theirs. But Pharaoh is unaffected. His heart “becomes hard” (v.13; there is no reflexive or passive idea to the verb yeḥezaq, as so many translations render it).

NOTES

9 ![]() (tannîn, “snake, serpent”) is usually used for larger reptiles (Ge 1:21; Dt 32:33) such as crocodiles (Eze 29:3) or a sea monster and leviathan (Job 7:12; Isa 27:1; 51:9; Jer 51:34). It also is often used metaphorically as a symbol of national empires and power (e.g., Dt 32:33; Ps 74:13; Eze 29:3).

(tannîn, “snake, serpent”) is usually used for larger reptiles (Ge 1:21; Dt 32:33) such as crocodiles (Eze 29:3) or a sea monster and leviathan (Job 7:12; Isa 27:1; 51:9; Jer 51:34). It also is often used metaphorically as a symbol of national empires and power (e.g., Dt 32:33; Ps 74:13; Eze 29:3).

11 ![]() (ḥakāmîm, “wise men”) are the learned and schooled men of that day.

(ḥakāmîm, “wise men”) are the learned and schooled men of that day.

![]() (mekaššepîm, “sorcerers, magicians”) is the intensive participle of the verb kšp (“to pray, offer prayers”). It is used in the OT only in the sense of sorcery.

(mekaššepîm, “sorcerers, magicians”) is the intensive participle of the verb kšp (“to pray, offer prayers”). It is used in the OT only in the sense of sorcery.

![]() (ḥarṭummîm, “magicians”) is always plural in the OT except in Daniel 2:10 (cf. Ge 41:8, 24; Ex 7:22; 8:7, 18–19; 9:11; Da 1:20; 2:2). It derives from an Egyptian loanword, ḥry-ḥbt, later shortened to ḥry-tp (“the chief of the priests”). In a seventh-century BC Assyrian document it appears as ḥar-ṭibi (D. B. Redford, A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph [Leiden: Brill, 1970], 203–4).

(ḥarṭummîm, “magicians”) is always plural in the OT except in Daniel 2:10 (cf. Ge 41:8, 24; Ex 7:22; 8:7, 18–19; 9:11; Da 1:20; 2:2). It derives from an Egyptian loanword, ḥry-ḥbt, later shortened to ḥry-tp (“the chief of the priests”). In a seventh-century BC Assyrian document it appears as ḥar-ṭibi (D. B. Redford, A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph [Leiden: Brill, 1970], 203–4).

![]() (belahaṭêhem, “by their secret arts”) is from the root

(belahaṭêhem, “by their secret arts”) is from the root ![]() (lûṭ, “to enwrap”; spelled here with an infixed he but without it in 7:22), hence the meaning “mysterious” or “secret.” The Egyptian word for magic is ḥikeʾ.

(lûṭ, “to enwrap”; spelled here with an infixed he but without it in 7:22), hence the meaning “mysterious” or “secret.” The Egyptian word for magic is ḥikeʾ.

2. First Plague: Water Turned to Blood (7:14–24)

14Then the LORD said to Moses, “Pharaoh’s heart is unyielding; he refuses to let the people go. 15Go to Pharaoh in the morning as he goes out to the water. Wait on the bank of the Nile to meet him, and take in your hand the staff that was changed into a snake. 16Then say to him, ‘The LORD, the God of the Hebrews, has sent me to say to you: Let my people go, so that they may worship me in the desert. But until now you have not listened. 17This is what the LORD says: By this you will know that I am the LORD: With the staff that is in my hand I will strike the water of the Nile, and it will be changed into blood. 18The fish in the Nile will die, and the river will stink; the Egyptians will not be able to drink its water.’”

19The LORD said to Moses, “Tell Aaron, ‘Take your staff and stretch out your hand over the waters of Egypt—over the streams and canals, over the ponds and all the reservoirs’—and they will turn to blood. Blood will be everywhere in Egypt, even in the wooden buckets and stone jars.”

20Moses and Aaron did just as the LORD had commanded. He raised his staff in the presence of Pharaoh and his officials and struck the water of the Nile, and all the water was changed into blood. 21The fish in the Nile died, and the river smelled so bad that the Egyptians could not drink its water. Blood was everywhere in Egypt.

22But the Egyptian magicians did the same things by their secret arts, and Pharaoh’s heart became hard; he would not listen to Moses and Aaron, just as the LORD had said. 23Instead, he turned and went into his palace, and did not take even this to heart. 24And all the Egyptians dug along the Nile to get drinking water, because they could not drink the water of the river.

COMMENTARY

14–18 God instructs Moses to go early (cf. 8:20) in the morning with his brother, Aaron, to intercept Pharaoh and his officials as they go out to the Nile (v.15; cf. v.20). Pharaoh’s purpose for going to the Nile with his officials remains unknown. Perhaps he is there to worship the Nile River god, Hapi. Moses and Aaron, however, are there to remind Pharaoh that “the LORD, the God of the Hebrews” (v.16) has sent them (5:1); yet the king of Egypt remains resolute in his defiance of this Lord. So God will help Pharaoh “know” who he is (v.17), insofar as Pharaoh protested in 5:2, “I do not know the LORD.” God will change the water of the Nile River into blood when Moses strikes it with his staff (v.17).

It is clear that v.17 and later 17:5 make Moses alone the user of the staff against the Nile River, but 7:19 has God instructing Moses to tell Aaron to stretch out his hand over all the waters in all Egypt so that they will be changed into blood. This hardly seems to be two different events of action by the two men. Verses 20–21 treat it as a single event; and it is not a clumsily overlooked inconsistency that leaves the trail of the divergent sources from which the material came. Instead, it is an “example of the phraseology by which an agent is said to do that which he commands or procures to be done” (Bush, 1:96; cf. Hos 8:1).

19–21 When Aaron stretches out his staff and strikes what the Egyptians regard as sacred, the Nile and the water all over Egypt turn to blood. What is the “blood”? W. M. Flinders Petrie (Egypt and Israel [London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1911], 25–36) was the first to suggest that the sequence of the plagues followed a natural cycle and all happened in one year. More recently Greta Hort (“The Plagues of Egypt”) traced this connected sequence by beginning with an unusually high Nile flood in July and August. The sources for the Nile’s inundation are the equatorial rains that fill the White Nile, which originates in east-central Africa (present-day Uganda) and flows sluggishly through swamps in eastern Sudan; and the Blue Nile and the Atbara River, which fill with melting snow from the mountains and become raging torrents filled with tons of red soil from the basins of both rivers—the higher the inundation, the deeper the color of the red waters.

In addition to this discoloration, a type of algae known as flagellates comes from the Sudanese swamps and Lake Tana along the White Nile and produces the stench and deadly fluctuation in the oxygen level of the river that proves to be fatal to fish. Such a process, at the command of God, seems to be the case for this first plague rather than any chemical change of the water into red and white corpuscles (cf. Joel 2:31—“the moon [will be changed] to blood”—or 2 Kings 3:22, where the water looked “like blood”).

Unlike other plagues and in agreement with this natural phenomenon, this plague does not stop suddenly. This explanation was accepted already by such conservatives as Keil and Delitzsch (1:478–79), Lange (20), and more recently Kitchen (NBD, 1000–1002). This change affected the “streams” (= seven [in Herodotus] branches of the Nile), the canals (to fertilize the fields), the ponds (left from the overflowing Nile), and the reservoirs (artificially made to store water for later use).

22–24 Once again Pharaoh’s magicians apply their “secret arts” and imitate the miracle sufficiently to blunt the force of it on Pharaoh’s conscience (v.22). The question of where they find any unblemished water if the fourfold water system in “all Egypt” (vv.19, 21) is affected is answered in v.24—subterranean water from freshly dug wells. The expression “all” or “every” must not be pressed in this case on the analogy of 9:6, 11, and 25 (cf. the obvious hyperbole of 10:5; Ge 41:57, “All the countries came to Egypt to buy grain”; Mt 3:5, “All Judea and the whole region of the Jordan” [emphases mine]). Bush, 1:78, chides, “If they had had any confidence in their own art, they would rather have attempted to turn the blood into water than . . . to ape the miracle of Moses . . . though there is no evidence of their succeeding even in this.” But Pharaoh remains unmoved and merely returns to his palace from the bloody river’s edge; his heart grows rigid and hard in spite of this evidence (v.23).

NOTES

19 ![]() (ûbaʿēṣîm ûbā ʾabānîm) is (lit.), “and in wooden [things] and in stone [things].” The NIV’s “in the wooden buckets and stone jars” is doubtful since vessels of wood and stone were not common in Egypt. Hyatt, 106, is most certainly incorrect—“even the sap in the trees and the springs . . . in stony places,” as is Cassuto, 99, when he conjectures that the water used to wash the idols of wood and stone also turned to blood (the preposition b he interpreted as “on”). Rawlinson, 1:172, had a better suggestion: “in the wooden and stone settlement tanks,” which were used for storing the Nile River water so that the sediment would sink before the water was used. Egypt often received no rain and never more than ten inches of rainfall per year in the delta.

(ûbaʿēṣîm ûbā ʾabānîm) is (lit.), “and in wooden [things] and in stone [things].” The NIV’s “in the wooden buckets and stone jars” is doubtful since vessels of wood and stone were not common in Egypt. Hyatt, 106, is most certainly incorrect—“even the sap in the trees and the springs . . . in stony places,” as is Cassuto, 99, when he conjectures that the water used to wash the idols of wood and stone also turned to blood (the preposition b he interpreted as “on”). Rawlinson, 1:172, had a better suggestion: “in the wooden and stone settlement tanks,” which were used for storing the Nile River water so that the sediment would sink before the water was used. Egypt often received no rain and never more than ten inches of rainfall per year in the delta.

23 ![]() (welō ʾ šāt libbô, “and [he] did not take even this to heart”) is an expression widely used in the OT (e.g., 9:21; cf. Hag 1:5, 7; 2:15, 18 with the verb śîm). It means simply, “pay attention.”

(welō ʾ šāt libbô, “and [he] did not take even this to heart”) is an expression widely used in the OT (e.g., 9:21; cf. Hag 1:5, 7; 2:15, 18 with the verb śîm). It means simply, “pay attention.”

3. Second Plague: Frogs (7:25–8:15)

25Seven days passed after the LORD struck the Nile. 8:1Then the LORD said to Moses, “Go to Pharaoh and say to him, ‘This is what the LORD says: Let my people go, so that they may worship me. 2If you refuse to let them go, I will plague your whole country with frogs. 3The Nile will teem with frogs. They will come up into your palace and your bedroom and onto your bed, into the houses of your officials and on your people, and into your ovens and kneading troughs. 4The frogs will go up on you and your people and all your officials.’”

5Then the LORD said to Moses, “Tell Aaron, ‘Stretch out your hand with your staff over the streams and canals and ponds, and make frogs come up on the land of Egypt.’”

6So Aaron stretched out his hand over the waters of Egypt, and the frogs came up and covered the land. 7But the magicians did the same things by their secret arts; they also made frogs come up on the land of Egypt.

8Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron and said, “Pray to the LORD to take the frogs away from me and my people, and I will let your people go to offer sacrifices to the LORD.”

9Moses said to Pharaoh, “I leave to you the honor of setting the time for me to pray for you and your officials and your people that you and your houses may be rid of the frogs, except for those that remain in the Nile.”

10“Tomorrow,” Pharaoh said.

Moses replied, “It will be as you say, so that you may know there is no one like the LORD our God. 11The frogs will leave you and your houses, your officials and your people; they will remain only in the Nile.”

12After Moses and Aaron left Pharaoh, Moses cried out to the LORD about the frogs he had brought on Pharaoh. 13And the LORD did what Moses asked. The frogs died in the houses, in the courtyards and in the fields. 14They were piled into heaps, and the land reeked of them. 15But when Pharaoh saw that there was relief, he hardened his heart and would not listen to Moses and Aaron, just as the LORD had said.

7:25–8:5 Seven days after the first plague has begun, God instructs Moses and Aaron to take their demands to the king’s palace (cf. 7:23; 7:25–8:1). If he refuses to grant their repeated request to go to the desert to worship the Lord, they are to announce in the set formula, “I will plague your whole country with frogs” (v.2). This is not to be a “sign” but a “plague” only (see Notes). In comparison with what is to come, this is only a trivial annoyance.

6–7 On Aaron’s signal frogs emerge from the water and “cover” the land, says the text with legitimate hyperbole (v.6). These pesky creatures, though regarded as sacred to the Egyptians, are God’s scourge to whip people into facing the living God. The intensification of the nuisance by Pharaoh’s magicians is totally ignored by him (v.7). Tons of croaking, crawling, creeping intruders are everywhere.

8–15 Why should the frogs so suddenly abandon their natural habitat in August during a high Nile and invade the homes, bedrooms, ovens, kneading troughs, and even the palace itself? And why should they likewise die off so suddenly? Hort, 95–98, finds the connection to be in the dead fish killed by flagellates. The frogs abandon all the polluted and overflowing waterways (cf. 7:19) and seek cover from the sun on dry land in homes where possibly the presence of some unadulterated water attracts them. However, since they have already been exposed to spores of bacillus anthracis from the death spread along the waterways, the frogs also collapse and die.

Pharaoh has finally been forced to acknowledge the power of Yahweh, not by the armies of men, but by squadrons of loathsome little frogs. Now he knows who this “LORD” is (cf. 5:2), and he accedes to Moses’ and Aaron’s request (v.8)—only to renege later on (v.15).

Moses’ response to Pharaoh’s desperate or, as some think, cynical plea is to dare Pharaoh to test his prophetic credentials (v.9) and, more importantly, the power of God (v.10) by setting the time when he wishes to be rid of this plague. Pharaoh’s quick response of “tomorrow” leads Moses to enter into some intensely earnest prayer (v.12, the whole scene recurs with Elijah in a similar daring contest of prayer with the prophets of Baal in 1 Kings 18:36–37). Moses’ freedom to negotiate on his own terms and then to have, as it were, God back him up is remarkable.

The frogs drop dead everywhere—in the houses, fields, and open courtyards (v.13). Frogs are piled up in heaps, and there is a firm reminder to aid Pharaoh’s wavering memory—the stench of dead frogs (v.14). Nevertheless, that fades and so does Pharaoh’s permission. This “relief” (hārwāḥâ, v.15) is worse than the plague for this proud king. People do not often learn the righteousness of God when granted mercy and favor (Ps 78:34–42; Isa 26:10).

NOTES

8:1[7:26] The rendering of the waw conjunction to introduce a purpose clause agrees with usage here in ![]() (weyaʿabedunî, “so that they may worship me”) and in 7:11–12; 8:7–8.

(weyaʿabedunî, “so that they may worship me”) and in 7:11–12; 8:7–8.

2[7:27] Surprisingly few Hebrew terms are used for the plagues in this narrative. Actually, only in 9:14 is the word ![]() (maggēpōt, “plagues”) used. Here it is

(maggēpōt, “plagues”) used. Here it is ![]() (nōgēp, “plague”). In 12:13 it is

(nōgēp, “plague”). In 12:13 it is ![]() (negep, “a hit, pestilence”); in 11:1,

(negep, “a hit, pestilence”); in 11:1, ![]() (negaʿ, “stroke”); and in 9:3, 15,

(negaʿ, “stroke”); and in 9:3, 15, ![]() (deber, “pestilence”). The NIV uniformly renders these as “plague.” Hebrew has “border” used as a metonym for Egypt’s “territory” or “land” (NIV has the “whole country”).

(deber, “pestilence”). The NIV uniformly renders these as “plague.” Hebrew has “border” used as a metonym for Egypt’s “territory” or “land” (NIV has the “whole country”).

![]() (ṣeparde ʿîm, “frogs”) may be the Hebrew equivalent of the Egyptian Arabic name dôda or, as Cole suggests (91), an onomatopoeic form that attempts to imitate the cacophony of their incessant croaks. Frogs were associated with the froghead goddess Heqet, who assisted women at childbirth. The scientific name for these frogs, which are similar to our toads, is Rama Mosaica. Frogs are only mentioned in the OT in connection with this plague (see Pss 78:45; 105:30). Notice in v.6 that “the frog [singular in Hebrew] came up” is again used for the collective (NIV, “frogs”). “Possibly the writer consciously used the sing. ‘frog’ [tsephardē ʿa]: the frogs were so numerous that they could no longer be distinguished; it is as if one humongous frog, one big monster has Egypt in its grip” (Houtman, 2:47).

(ṣeparde ʿîm, “frogs”) may be the Hebrew equivalent of the Egyptian Arabic name dôda or, as Cole suggests (91), an onomatopoeic form that attempts to imitate the cacophony of their incessant croaks. Frogs were associated with the froghead goddess Heqet, who assisted women at childbirth. The scientific name for these frogs, which are similar to our toads, is Rama Mosaica. Frogs are only mentioned in the OT in connection with this plague (see Pss 78:45; 105:30). Notice in v.6 that “the frog [singular in Hebrew] came up” is again used for the collective (NIV, “frogs”). “Possibly the writer consciously used the sing. ‘frog’ [tsephardē ʿa]: the frogs were so numerous that they could no longer be distinguished; it is as if one humongous frog, one big monster has Egypt in its grip” (Houtman, 2:47).

4. Third Plague: Gnats (8:16–19)

16Then the LORD said to Moses, “Tell Aaron, ‘Stretch out your staff and strike the dust of the ground,’ and throughout the land of Egypt the dust will become gnats.” 17They did this, and when Aaron stretched out his hand with the staff and struck the dust of the ground, gnats came upon men and animals. All the dust throughout the land of Egypt became gnats. 18But when the magicians tried to produce gnats by their secret arts, they could not. And the gnats were on men and animals.

19The magicians said to Pharaoh, “This is the finger of God.” But Pharaoh’s heart was hard and he would not listen, just as the LORD had said.

16–17 The third plague begins without warning to Pharaoh or his magicians. God again uses the outstretched staff in the hand of Aaron to initiate this plague. Aaron strikes the dust of the ground, just as he struck the Nile in the first plague (7:20), and “all the dust throughout the land of Egypt became gnats” (8:17, emphasis mine)—another hyperbole to stress the tremendous extent and intensity of this pestilence (cf. 7:19, 21; 9:6, 19, 25; 10:5).

The word “gnats” (kinnîm) occurs five times in this passage and nowhere else (except in Ps 105:31, unless another reading is verified in Isa 51:6). It is debatable whether this word means “lice” (as in the KJV, Peshitta, Josephus, and Targum Onqelos) or “gnats, mosquitoes,” as we favor with most interpreters, especially the translators of the LXX (who had firsthand acquaintance with Egypt [Gk. skniphes]).

18–19 On their fourth attempt to duplicate the miracles of Moses and Aaron, the Egyptian magicians admit defeat (v.18). Nevertheless, in spite of what success they experienced in the previous three encounters (and it may well have been through slight of hand, given the advance notice of the nature of the plague or sign in those cases—or perhaps it was just plain demonic, supernatural empowerment to mimic God’s power), they now realize that the plague of the gnats is the “finger of God” (v.19; cf. Dt 9:10; Mt 12:28; Lk 11:20), i.e., the result of his power (see Notes). “Finger” signifies God alone is responsible for this plague, not Moses and/or Aaron. But Pharaoh is not persuaded in his heart and mind; he remains adamant and opposed to any Israelite demands.

NOTES

7[8:3] On “secret arts,” see Notes on 7:11.

9[8:5] ![]() (hitpā ʾēr ʿālay) is a difficult phrase. The LXX has “appoint for me,” but more literally it is “glorify yourself over me.” This is more than an ordinary courtesy; it is an invitation to give Pharaoh the upper hand for the moment. The NIV translates it, “I leave to you the honor of.” Houtman, 2:48, translates it, “Please have it your way,” by emending the text from pʾr to bʾr, “make it clear [to me].”

(hitpā ʾēr ʿālay) is a difficult phrase. The LXX has “appoint for me,” but more literally it is “glorify yourself over me.” This is more than an ordinary courtesy; it is an invitation to give Pharaoh the upper hand for the moment. The NIV translates it, “I leave to you the honor of.” Houtman, 2:48, translates it, “Please have it your way,” by emending the text from pʾr to bʾr, “make it clear [to me].”

10[8:6] ![]() (lemāḥār, “tomorrow”; lit., “for tomorrow”) is Pharaoh’s answer to Moses’ question: (lit.) “For when” or “For what date shall I ask in prayer to God?” (v.9). Pharaoh may have suspected that Moses is stalling for time, so he picks the earliest possible time for the removal of the plague that Moses may not have anticipated or thought of using.

(lemāḥār, “tomorrow”; lit., “for tomorrow”) is Pharaoh’s answer to Moses’ question: (lit.) “For when” or “For what date shall I ask in prayer to God?” (v.9). Pharaoh may have suspected that Moses is stalling for time, so he picks the earliest possible time for the removal of the plague that Moses may not have anticipated or thought of using.

12[8:8] ![]() (wayyiṣʿaq, “and [Moses] cried out”) is a strong expression to denote the earnestness and intensity of the prayer.

(wayyiṣʿaq, “and [Moses] cried out”) is a strong expression to denote the earnestness and intensity of the prayer.

16[8:12] ![]() (kinnîm, “gnats”) appears in vv.17–18[13–14] as a feminine collective (hakkinnam) since it is governed by the third person singular verb

(kinnîm, “gnats”) appears in vv.17–18[13–14] as a feminine collective (hakkinnam) since it is governed by the third person singular verb ![]() (tehî, lit., “she came”). As prolific as is the dust, so there come zillions of gnats!

(tehî, lit., “she came”). As prolific as is the dust, so there come zillions of gnats!

19[8:15] ![]() (ʾeṣbaʿ ʾelōhîm, “finger of God”) is a figure of speech called synecdoche, where a portion (here of the divine person) is used to denote the totality (of his power; see “finger of God” in Ex 31:18; Ps 8:3; Lk 11:20; “hand of God” in 1Sa 6:9; Ps 109:27). Cook, 281, argues that the expression is thoroughly Egyptian. It either attributes this act of God as being hostile to one of their protecting gods (e.g., the god of the earth, Set), or it equates Aaron’s wooden rod with the finger of a specific deity (see, e.g., ch. 153 of the Egyptian Book of the Dead). Synecdoche is the preferable explanation, because the magicians’ attitude is contrasted with Pharaoh’s hardheartedness.

(ʾeṣbaʿ ʾelōhîm, “finger of God”) is a figure of speech called synecdoche, where a portion (here of the divine person) is used to denote the totality (of his power; see “finger of God” in Ex 31:18; Ps 8:3; Lk 11:20; “hand of God” in 1Sa 6:9; Ps 109:27). Cook, 281, argues that the expression is thoroughly Egyptian. It either attributes this act of God as being hostile to one of their protecting gods (e.g., the god of the earth, Set), or it equates Aaron’s wooden rod with the finger of a specific deity (see, e.g., ch. 153 of the Egyptian Book of the Dead). Synecdoche is the preferable explanation, because the magicians’ attitude is contrasted with Pharaoh’s hardheartedness.

5. Fourth Plague: Flies (8:20–32)

20Then the LORD said to Moses, “Get up early in the morning and confront Pharaoh as he goes to the water and say to him, ‘This is what the LORD says: Let my people go, so that they may worship me. 21If you do not let my people go, I will send swarms of flies on you and your officials, on your people and into your houses. The houses of the Egyptians will be full of flies, and even the ground where they are.

22“‘But on that day I will deal differently with the land of Goshen, where my people live; no swarms of flies will be there, so that you will know that I, the LORD, am in this land. 23I will make a distinction between my people and your people. This miraculous sign will occur tomorrow.’”

24And the LORD did this. Dense swarms of flies poured into Pharaoh’s palace and into the houses of his officials, and throughout Egypt the land was ruined by the flies.

25Then Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron and said, “Go, sacrifice to your God here in the land.”

26But Moses said, “That would not be right. The sacrifices we offer the LORD our God would be detestable to the Egyptians. And if we offer sacrifices that are detestable in their eyes, will they not stone us? 27We must take a three-day journey into the desert to offer sacrifices to the LORD our God, as he commands us.”

28Pharaoh said, “I will let you go to offer sacrifices to the LORD your God in the desert, but you must not go very far. Now pray for me.”

29Moses answered, “As soon as I leave you, I will pray to the LORD, and tomorrow the flies will leave Pharaoh and his officials and his people. Only be sure that Pharaoh does not act deceitfully again by not letting the people go to offer sacrifices to the LORD.”

30Then Moses left Pharaoh and prayed to the LORD, 31and the LORD did what Moses asked: The flies left Pharaoh and his officials and his people; not a fly remained. 32But this time also Pharaoh hardened his heart and would not let the people go.

COMMENTARY

20–21 As in the first plague, Moses must intercept Pharaoh again as he goes down to the Nile early in the morning. Cook, 281, postulates that the occasion for this royal procession is to open the solemn festival held 120 days after the first rising of the Nile, i.e., at about the end of October or the beginning of November. This time Pharaoh and all of his people and their houses are threatened with a plague of “flies” (heʿārōb).

Modern attempts to identify these creatures include (1) beasts, reptiles, and insects, supposing the word represents an Arabic root meaning “unmixed” (cf. that meaning in 12:38; NIV, “other people”); (2) the “dogfly,” as rendered by the LXX (kynomuia), a bloodsucking gadfly which, however, appears in the spring of the year and not the fall, when this plague occurs; (3) the ordinary housefly, which serves in Isaiah 7:18 as a symbol for Egypt (though the Hebrew word there is zebûb); and (4) the beetle Blatta Orientalis, which gnaws clothes, furniture, plants, humans, and beasts, arrives in late November, and bears a close resemblance to the Hebrew ʿārōb in an Egyptian word retained in Coptic, abeb (Cook, 490; Knight, 63–64, compares it to the scarab beetle).

It seems best to follow Hort, 99, 102, and say that the fly Stomoxys Calcitrans best fulfills all the conditions of the text. This fly multiplies rapidly in tropical or subtropical regions (hence the delta with its Mediterranean climate would be exempt) in the fall by laying its six hundred to eight hundred eggs in dung or rotting plant debris. When it is fully grown, the fly prefers to infest houses and stables, and it bites both humans and animals, usually in the lower extremities. Thus it becomes the principal transmitter of skin anthrax (see the sixth plague), which it contracts by crawling over the carcasses of animals that have died of internal anthrax.

22–24 By inaugurating a “distinction” (see Notes) between Moses’ people and Pharaoh’s people, God aids those hardened Egyptian hearts who suspect that nothing more than chance or difficult times were involved in the preceding three plagues. This distinction is found in the fourth, fifth, seventh, ninth, and tenth plagues (v.23; 9:4, 6, 26; 10:23; 11:7). The purpose of this preferential treatment of Israel is to teach Pharaoh and the Egyptians that the Lord God of Israel is in the midst of this land doing these works; it is not one of their local deities.

Gods were thought by ancient Near Easterners to possess no power except on their own home ground. But not so here! The innocent are being delivered and the guilty afflicted because Israel’s God is in their midst. God will again do a “miraculous sign” designed to evoke the Egyptians’ faith and their release of Israel (see Notes on 4:8).

In another innovative feature Moses announces in advance when the plague is due to strike, giving the Egyptians time to repent. This advance notice is found in the fourth, fifth, sixth, eighth, and tenth plagues (v.21; 9:5, 18; 10:4; 11:4). Moreover, Pharaoh and his court are again singled out as the first victims of this plague because of the heavy responsibility they bear for their intransigence (vv.21, 24).

25–32 Moses’ claim that if Israel sacrificed animals in Egypt, it would be extremely offensive to the Egyptians has been challenged by some commentators as a clever ruse on Moses’ part. Yet Rylaarsdam, 901, documents a violent Egyptian reaction to Jewish sacrifices in the fifth-century BC colony at Elephantine (A. E. Cowley, Aramaic Papyri of the Fifth Century BC [Oxford: Clarendon, 1923], 108–22). Thus Moses rejects Pharaoh’s counteroffer to allow Israel to sacrifice in Egypt (v.25).

Finally, Pharaoh concedes the long-denied permission. With a note of self-importance he pontificates, “I [ʾānōkî] will let you go . . . but [raq] you must not go very far” (v.28). And as though to show what his real thoughts are all along, he quickly adds, “Now pray for me.” Pharaoh shrewdly takes advantage of the fact that Moses has not said this time that they must go outside the country to worship. So Pharaoh—Venenum in cauda est! (“a snake lurks in the grass,” Houtman, 2:59), slips in the words “in the land” with his apparently concessive permission.

Moses will not be put down, for his mission likewise has dignity; thus he, too, begins with the pronoun “I” (ʾānōkî): “I am leaving you, and I will pray” (v.29, lit. tr.). Moses, with an obvious rebuke, says in effect, “Don’t you ‘however’ me when you are in such a poor bargaining position.” But then on a courteous note, with a switch to the third-person form of address, he continues, “Only [raq] be sure that Pharaoh does not act deceitfully again.”

The plague is removed through Moses’ prayer (cf. Elijah, 1Ki 18:42; Amos, Am 7:2, Am 7:5). So effective is the power of prayer and the evidence that God is in their midst that “not a fly remained” (v.31). But Pharaoh once again (cf. second plague, 8:15) returns to his hard-nosed stand once he obtains the physical relief he desires.

NOTES

21[17] ![]() (ʾašer . . . ʿāleyhā, “where . . . are”) is literally, “on which, where.” “Even the ground where they [i.e., the Egyptians] are” is sharply contrasted with v.22’s ʿāleyhā (“Where [my people live]”).

(ʾašer . . . ʿāleyhā, “where . . . are”) is literally, “on which, where.” “Even the ground where they [i.e., the Egyptians] are” is sharply contrasted with v.22’s ʿāleyhā (“Where [my people live]”).

22[18] The LXX renders ![]() (wehiplêtî, “I will deal differently”) as “I will marvelously glorify,” misunderstanding it as from

(wehiplêtî, “I will deal differently”) as “I will marvelously glorify,” misunderstanding it as from ![]() (pālā ʾ). The term occurs again in 33:16: “What else will distinguish me and your people from all the other people on . . . earth?” (cf. also 9:4; 11:7).

(pālā ʾ). The term occurs again in 33:16: “What else will distinguish me and your people from all the other people on . . . earth?” (cf. also 9:4; 11:7).

![]() (gōšen, “Goshen”) was the eastern delta region. About fifty miles northeast of modern Cairo is the Wadi Tumilat, a valley five or six miles wide and thirty miles long ending in Lake Timsah, now part of the present-day Suez Canal. The name “Goshen” in an Egyptian (hieroglyphic) name is spelled (like the other two delta names) with a word beginning with a bull, ka (= Hebrew first syllable Go).

(gōšen, “Goshen”) was the eastern delta region. About fifty miles northeast of modern Cairo is the Wadi Tumilat, a valley five or six miles wide and thirty miles long ending in Lake Timsah, now part of the present-day Suez Canal. The name “Goshen” in an Egyptian (hieroglyphic) name is spelled (like the other two delta names) with a word beginning with a bull, ka (= Hebrew first syllable Go).

23[19] ![]() (pedūt, “a distinction”; GK 7014) is correct here even though pedūt generally is rendered “redemption” or “deliverance” (a concept used of the impending exodus in 6:6; cf. gā ʾal, “to redeem [as a kinsman]”). To emend the text to read pelut (“separation”) is unwarranted since that nominal form would be a hapax legomenon. I agree with G. I. Davies (“The Hebrew Text of Exodus VIII 19 [EVV 23]: An Emendation,” VT 24 [1974]: 489–92) that the letter d was omitted by haplography from the text, which originally read prdt (from the verb prd, “to separate”) in the Hiphil, used three times in the OT with bên (“between”; Ru 1:17; 2Ki 2:11; Pr 18:18).

(pedūt, “a distinction”; GK 7014) is correct here even though pedūt generally is rendered “redemption” or “deliverance” (a concept used of the impending exodus in 6:6; cf. gā ʾal, “to redeem [as a kinsman]”). To emend the text to read pelut (“separation”) is unwarranted since that nominal form would be a hapax legomenon. I agree with G. I. Davies (“The Hebrew Text of Exodus VIII 19 [EVV 23]: An Emendation,” VT 24 [1974]: 489–92) that the letter d was omitted by haplography from the text, which originally read prdt (from the verb prd, “to separate”) in the Hiphil, used three times in the OT with bên (“between”; Ru 1:17; 2Ki 2:11; Pr 18:18).

24[20] ![]() (ʾereṣ . . . tiššāḥēt, “the land was ruined”) contrasts with Psalm 78:45, which says that the flies “devoured them” (wayyoʾkelēm), i.e., the Egyptians themselves, while it was the frogs that “devastated [= ruined] them” (wattašḥitēm). Apparently both plagues had devastating effects.

(ʾereṣ . . . tiššāḥēt, “the land was ruined”) contrasts with Psalm 78:45, which says that the flies “devoured them” (wayyoʾkelēm), i.e., the Egyptians themselves, while it was the frogs that “devastated [= ruined] them” (wattašḥitēm). Apparently both plagues had devastating effects.

6. Fifth Plague: Cattle Murrain (9:1–7)

1Then the LORD said to Moses, “Go to Pharaoh and say to him, ‘This is what the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, says: “Let my people go, so that they may worship me.” 2If you refuse to let them go and continue to hold them back, 3the hand of the LORD will bring a terrible plague on your livestock in the field—on your horses and donkeys and camels and on your cattle and sheep and goats. 4But the LORD will make a distinction between the livestock of Israel and that of Egypt, so that no animal belonging to the Israelites will die.’”

5The LORD set a time and said, “Tomorrow the LORD will do this in the land.” 6And the next day the LORD did it: All the livestock of the Egyptians died, but not one animal belonging to the Israelites died. 7Pharaoh sent men to investigate and found that not even one of the animals of the Israelites had died. Yet his heart was unyielding and he would not let the people go.

COMMENTARY

1–4 The fifth plague is patterned after the second: Moses must go to Pharaoh’s palace and announce the next pestilence (v.1). A “terrible plague” (v.3) will be brought, not by God’s “finger,” as the Egyptian magicians put it in 8:19, but by his “hand” (v.3). It will fall on all the cattle in the field. There is no need to press the expression “all the livestock” (v.6) to mean each and every animal and then find there are no Egyptian cattle left for the seventh plague (vv.19, 25), for it is already plain in v.3 that the plague affects only those cattle “in the field.” Normally Egyptian cattle were stabled from May through December, during the flood and the drying-off periods when the pastures were waterlogged. Thus some of the cattle are already being turned out to pasture in the south; so it must be sometime in the month of January. These cattle are then affected when they come into contact with the heaps of dead frogs left from the second plague and died of Bacillus Anthracis, the hoof and mouth disease.

Israelite cattle are exempted from the plague possibly because the delta would be slower in recovering from the effects of the flood, which occurs further downstream. Also, the Israelites’ different attitude toward corpses—they took precautions to deal with dead carcasses—may have spared their own cattle. Rawlinson, 1:199, suggests that the miraculous nature of this plague can be seen in (1) the announcement and timing of the pestilence (vv.3–6), (2) the severity of its effect (v.6), and (3) the selectivity of its impact on the Egyptians’ cattle only (v.7). This is the second plague in which God distinguishes between the Egyptians and the Israelites.

5–7 The interval between the announcement and the morrow (v.5), when the fifth plague is to take effect, will allow time for a believing response from Pharaoh and the Egyptians. Presumably some believe and attempt to rescue their animals by bringing them in from the fields. Others purposely delay turning their cattle out to pasture.

When Pharaoh hears that all the Israelite cattle have miraculously escaped the cattle plague, he sends envoys to Goshen to investigate (v.7). The rumor is true: “Not one animal belonging to the Israelites died” (v.6). Pharaoh probably has his own explanations and rationalizations, for his position and heart again become resolute and unyielding.

Meanwhile, another part of Egypt’s wide array of gods is hard hit: the Apis, or sacred bull Ptah; the calf god Ra; the cows of Hathor; the jackal-headed god Anubis; and the bull Bakis of the god Mentu. The evidence is too strong to be mere coincidence: (1) the time has been set by Yahweh, the God of the Hebrews (v.5); (2) a “distinction” is made between the cattle of the two peoples (v.4); and (3) the results are total—all Egyptian cattle “in the field” (v.3) die, but not one head of Israelite livestock perishes.

3 G. S. Ogden (“Notes on the Use of ![]() in Exodus IX. 3,” VT 17 [1967]: 483–84) asks why the participle of hyh occurs here—

in Exodus IX. 3,” VT 17 [1967]: 483–84) asks why the participle of hyh occurs here—![]() (hôyâ, “[The hand of the LORD] will bring”)—and no other time in the OT when one would expect an imperfect or a nominal clause without a verb. His totally satisfactory answer is: (1) the use of the participle plus hinnēh lends itself to denoting an impending divine action, and (2) it conforms to a pattern in which the participle is used five times in Moses’ and Aaron’s petition for an Israelite pilgrimage, when they threaten Pharaoh with what God will do should Pharaoh fail to comply (7:17; 8:2; 9:3, 14; 10:4). Thus the participial form is “manufactured” to conform to this pattern.

(hôyâ, “[The hand of the LORD] will bring”)—and no other time in the OT when one would expect an imperfect or a nominal clause without a verb. His totally satisfactory answer is: (1) the use of the participle plus hinnēh lends itself to denoting an impending divine action, and (2) it conforms to a pattern in which the participle is used five times in Moses’ and Aaron’s petition for an Israelite pilgrimage, when they threaten Pharaoh with what God will do should Pharaoh fail to comply (7:17; 8:2; 9:3, 14; 10:4). Thus the participial form is “manufactured” to conform to this pattern.

See Notes on 8:2 for ![]() (deber, “plague, pestilence”). The word occurs in some fifty places either of the Lord’s judgment on a people (e.g., Lev 26:25; Nu 14:12; 2Sa 24:13–15) or as that from which the Lord is able to save his own (Ps 91:3).

(deber, “plague, pestilence”). The word occurs in some fifty places either of the Lord’s judgment on a people (e.g., Lev 26:25; Nu 14:12; 2Sa 24:13–15) or as that from which the Lord is able to save his own (Ps 91:3).

Ever since W. F. Albright’s remark (Archaeology and the Religion of Israel [Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1942], 96) that it was only in “the eleventh century [BC] that camel-riding nomads first appear in our documentary sources,” it has been customary to regard verses such as Genesis 12:16 (Abraham’s camels in Egypt), 37:25 (an Ishmaelite camel caravan headed for Egypt), and here—![]() (baggemallîm, “on the camels”)—as being anachronistic. Cassuto, 111, however, affirms that domesticated camels were in Egypt during Moses’ time even though no scholarly agreement exists on the time of their original domestication (see also Kitchen, “Camel,” NBD, 181–83).

(baggemallîm, “on the camels”)—as being anachronistic. Cassuto, 111, however, affirms that domesticated camels were in Egypt during Moses’ time even though no scholarly agreement exists on the time of their original domestication (see also Kitchen, “Camel,” NBD, 181–83).

4 On ![]() (wehiplâ, “a distinction”), see Notes on 8:22 and 8:23.

(wehiplâ, “a distinction”), see Notes on 8:22 and 8:23.

7. Sixth Plague: Boils (9:8–12)

8Then the LORD said to Moses and Aaron, “Take handfuls of soot from a furnace and have Moses toss it into the air in the presence of Pharaoh. 9It will become fine dust over the whole land of Egypt, and festering boils will break out on men and animals throughout the land.”

10So they took soot from a furnace and stood before Pharaoh. Moses tossed it into the air, and festering boils broke out on men and animals. 11The magicians could not stand before Moses because of the boils that were on them and on all the Egyptians. 12But the LORD hardened Pharaoh’s heart and he would not listen to Moses and Aaron, just as the LORD had said to Moses.

COMMENTARY

8–9 Like the third plague, this one, which completes the second cycle, is sent unannounced. For the first time the lives of humans are attacked and endangered; thus, it is a foreshadowing of the tenth and most dreadful of all the plagues. With a touch of divine irony and poetic justice, Moses and Aaron are each to take two handfuls (the form is dual) of soot from a lime kiln or brick-making furnace, the symbol of Israel’s bondage (v.8; see 1:14; 5:7–19). The soot is likely placed in a container and carried to Pharaoh’s presence, where Moses tosses it into the air. This act is a symbolic action much like those of the latter prophets (e.g., Jeremiah’s smashing of the pottery jar in Jer 19 or Ezekiel’s siege preparations and prophetically symbolic actions in Eze 4–5). There was also a logical connection between the soot created by the sweat of God’s enslaved people and the judgment that is to afflict the bodies of the enslavers.

10–12 When the soot is tossed skyward, festering boils break out on all the Egyptians and their animals (vv.9–10). Attempts to identify this malady have produced various results (see Notes).

In a humorous aside, v.11 notes that the magicians (who bowed out in plague three and are unnoticed, though possibly present, in plagues four and five) literally (and vocationally) “could not stand” before Moses. The same can be said for all the Egyptians. Here for the first time God hardens Pharaoh’s heart (v.12)—a seconding, as it were, of his own motion made in each of the preceding five plagues.

NOTES

8 ![]() (pîaḥ) is “soot,” not “ashes” taken from sacrifices, which are called

(pîaḥ) is “soot,” not “ashes” taken from sacrifices, which are called ![]() (ʾēper; cf. Nu 19:10). This hapax legomenon is from the verb

(ʾēper; cf. Nu 19:10). This hapax legomenon is from the verb ![]() (pûaḥ, “to breathe, blow”).

(pûaḥ, “to breathe, blow”).

![]() (kibšān, “furnace”) appears four times in the Bible: Genesis 19:28 as a simile for the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Exodus 19:18 as a simile for the theophany on Mount Sinai, and here in vv.8 and 10. Cook, 490, lists the Egyptian and Coptic word kabusa, meaning “anthrax” or “carbo.” Four other Hebrew words are used elsewhere in the OT for ovens or furnaces. That these kilns were used to make bricks along with the more usual sun-dried bricks is attested in the New Kingdom period.

(kibšān, “furnace”) appears four times in the Bible: Genesis 19:28 as a simile for the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Exodus 19:18 as a simile for the theophany on Mount Sinai, and here in vv.8 and 10. Cook, 490, lists the Egyptian and Coptic word kabusa, meaning “anthrax” or “carbo.” Four other Hebrew words are used elsewhere in the OT for ovens or furnaces. That these kilns were used to make bricks along with the more usual sun-dried bricks is attested in the New Kingdom period.

9–10 ![]() (šeḥîn, “boils”) has an Arabic cognate that means “to be hot.” This sickness is associated with Job (Job 2:7–8) and Hezekiah (2Ki 20:7; Isa 38:21) and with various skin diseases (Lev 13:18–23).

(šeḥîn, “boils”) has an Arabic cognate that means “to be hot.” This sickness is associated with Job (Job 2:7–8) and Hezekiah (2Ki 20:7; Isa 38:21) and with various skin diseases (Lev 13:18–23).

![]() (ʾabaʿbuʿōt, “blisters, pustules”; NIV, “festering”) is from an assumed verb buʿ (“to swell up”); but Cook, 490, points to the Egyptian bʿbʿ (“to drink”), which in Coptic means “to overflow.” The initial aleph in the Hebrew spelling is no special problem. Notice the slight difference in the expressions between v.9 and v.10 (lit. tr.): “Boils breaking out in pustules” (v.9) and “boils of pustules breaking out” (v.10).

(ʾabaʿbuʿōt, “blisters, pustules”; NIV, “festering”) is from an assumed verb buʿ (“to swell up”); but Cook, 490, points to the Egyptian bʿbʿ (“to drink”), which in Coptic means “to overflow.” The initial aleph in the Hebrew spelling is no special problem. Notice the slight difference in the expressions between v.9 and v.10 (lit. tr.): “Boils breaking out in pustules” (v.9) and “boils of pustules breaking out” (v.10).

Various suggestions for the malady are (1) smallpox (Cassuto), (2) Nile blisters similar to scarlet fever (Keil and Delitzsch), (3) skin anthrax (Hort, 101–3), and (4) inflammations or blains that become malignant ulcers (Bush, Greenberg). We side with Hort, since Deuteronomy 28:35 limits this plague principally to the lower extremities of the body—on the knees and legs. Furthermore, the black soot is especially suited, for anthrax (cf. anthracite coal) is a sort of black, burning abscess often occurring with cattle murrain.

The flies of the fourth plague (Stomoxys Calcitrans) have generally been blamed as the carriers of the anthrax spores, but they are totally removed at the conclusion of that plague. Presumably this is another generation of flies (another batch can come in twenty-seven to thirty-seven days). After animals or humans are bitten on the legs by these flies, a small bluish-red pustule with a central depression in the middle of the swelling appears after two or three days. The center of the boil dries up only to have new boils swell up, and the skin festers as though it has been burnt and then peels off (Hort, 101).

8. Seventh Plague: Hail (9:13–35)

13Then the LORD said to Moses, “Get up early in the morning, confront Pharaoh and say to him, ‘This is what the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, says: Let my people go, so that they may worship me, 14or this time I will send the full force of my plagues against you and against your officials and your people, so you may know that there is no one like me in all the earth. 15For by now I could have stretched out my hand and struck you and your people with a plague that would have wiped you off the earth. 16But I have raised you up for this very purpose, that I might show you my power and that my name might be proclaimed in all the earth. 17You still set yourself against my people and will not let them go. 18Therefore, at this time tomorrow I will send the worst hailstorm that has ever fallen on Egypt, from the day it was founded till now. 19Give an order now to bring your livestock and everything you have in the field to a place of shelter, because the hail will fall on every man and animal that has not been brought in and is still out in the field, and they will die.’”

20Those officials of Pharaoh who feared the word of the LORD hurried to bring their slaves and their livestock inside. 21But those who ignored the word of the LORD left their slaves and livestock in the field.

22Then the LORD said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand toward the sky so that hail will fall all over Egypt—on men and animals and on everything growing in the fields of Egypt.” 23When Moses stretched out his staff toward the sky, the LORD sent thunder and hail, and lightning flashed down to the ground. So the LORD rained hail on the land of Egypt; 24hail fell and lightning flashed back and forth. It was the worst storm in all the land of Egypt since it had become a nation. 25Throughout Egypt hail struck everything in the fields—both men and animals; it beat down everything growing in the fields and stripped every tree. 26The only place it did not hail was the land of Goshen, where the Israelites were.

27Then Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron. “This time I have sinned,” he said to them. “The LORD is in the right, and I and my people are in the wrong. 28Pray to the LORD, for we have had enough thunder and hail. I will let you go; you don’t have to stay any longer.”

29Moses replied, “When I have gone out of the city, I will spread out my hands in prayer to the LORD. The thunder will stop and there will be no more hail, so you may know that the earth is the LORD’s. 30But I know that you and your officials still do not fear the LORD God.”

31(The flax and barley were destroyed, since the barley had headed and the flax was in bloom. 32The wheat and spelt, however, were not destroyed, because they ripen later.)

33Then Moses left Pharaoh and went out of the city. He spread out his hands toward the LORD; the thunder and hail stopped, and the rain no longer poured down on the land. 34When Pharaoh saw that the rain and hail and thunder had stopped, he sinned again: He and his officials hardened their hearts. 35So Pharaoh’s heart was hard and he would not let the Israelites go, just as the LORD had said through Moses.

13–19 As in the first (7:15) and fourth (8:20) plagues, Moses is to begin this third cycle of plagues by rising early in the morning to confront Pharaoh with the Lord’s message (v.13). From these early days in February until the time of the tenth and climactic plague, Pharaoh will spend approximately eight of the most dreadful weeks he has ever known.

To underscore further the theological significance of these weeks and their events, God prompts Moses to preface his latest announcement of divine judgment with a long message filled with doctrinal instruction. This unprecedented message is calculated to move Pharaoh and his subjects from rebellion to belief in Israel’s God. Its ominous contents include the following:

- 1. An announcement that God will vent the “full force” (v.14; i.e., “all the remaining plagues”; cf. 29:12 with Greenberg, 160) of the plagues on Egypt so that no one will doubt that there is anyone like this God in all the earth.

- 2. A reminder that previous pestilences and plagues may well have swept both king and people off the face of the earth had not God deliberately and purposely spared them for one important reason: that his power and name might be heralded throughout the earth by means of Pharaoh’s stupidity (vv.15–16).

- 3. A declaration that in denying the release of Israel, Pharaoh has acted as an obstructionist against Almighty God himself (v.17).

- 4. A threat that Egypt will experience the worst hailstorm it has ever seen in its history (v.18).

- 5. An extraordinary feature that provides for those Egyptians who believe Moses’ words are a means of escape from the effects of the storm (v.19).

The seventh plague will be judgment with the expectation that it may result in the blessing of belief and trust. Had not Abraham been given this mission to be a means of blessing to “all peoples on earth” (Ge 12:3)? And has not the theme “that the Egyptians might know that I am the LORD” (or slight variations) appeared frequently in the midst of these plagues (7:5; 8:10; 9:14, 16, 29–30; cf. also 14:4, 18)? Moses will sigh over Israel (Nu 14:11), “How long will these people treat me with contempt? How long will they refuse to believe in me, in spite of all the miraculous signs I have performed among them?” The same words apply here.

The months of leniency are almost over. Now the full blast of the ensuing plagues will penetrate directly to Pharaoh’s “heart” (v.14; NIV, “against you”). The “heart” (lēb; GK 4213) does not signify “his person,” as nepeš (GK 5883) can (Keil and Delitzsch, 1:489); rather, it refers to his inner being, nature, and seared conscience. His pride and arrogance will be tossed to the wind as the terrors of these new plagues force him in perplexed and desperate sorrow of soul literally to beg the Israelites to leave his presence immediately.

Yet Pharaoh is no mere pawn to be toyed with at will, for the object is that he too may come to experience personally and believe (“know”) the incomparability of God’s person and greatness. The superlative rating of his deeds (untr. in NIV)—none “like it” (kāmōhû, of the hailstorm in vv.18, 24; of the locusts in 10:6)—should lead the king and his people to the identical rating of God’s person (no one “like you,” kāmōkâ, 15:11; kāmōnî, “like me,” 9:14).

20–26 Rainfall comes only occasionally in Upper Egypt; thus, the prediction of a severe hailstorm accompanied by a violent electrical storm is probably greeted with much skepticism. Only the delta receives on an average about ten inches of rainfall per year, while Upper Egypt has one inch or, more often, none. But some fear “the word of the LORD” (v.20) and act accordingly. This is belief as it should be, resulting in appropriate action based on confidence in God’s word. Some Egyptians receive Moses’ words as being from God himself, for they become a part of that mixed company of Gentile believers who leave Egypt with Israel (see 12:38).

In the three plagues of the third cycle (9:10; 10:13, 20), Moses apparently loses his shyness and diffidence, for he is the one who now stretches forth his staff and his hand (v.22; cf. Aaron’s leading role in the first three plagues: 7:19–20; 8:6, 17). Hail joined by unannounced thunder and balls of fire (see Notes) that run along the ground (v.23) provide Egypt with the most spectacular display in her history (see Notes on vv.18, 23, 24).

The destruction is devastating. Five times in vv.24–25 the word kol (“all, everything”) is used; yet it is used hyperbolically and not literally, because the first two occurrences of kol (“in all Egypt,” vv.24–25a; NIV, “throughout Egypt”) are immediately qualified in v.26 to exempt the land of Goshen, where the Hebrews live. Nevertheless, even though the storm does not take every single tree, herb, or creature in the field, it is tragic enough to impress even the most calloused individual.

27–30 Pharaoh, obviously shaken, concedes the point: “I have sinned,” he admits, though he includes the face-saving qualifier “this time.” The question is, however, what makes this plague any different than the rest—except its severity. Only when the Lord begins to hurt Pharaoh does he (momentarily) seek him (cf. Ps 78:34). Like Jeremiah (Jer 12:1), Pharaoh declared that Yahweh (not Elohim!) is in the right and that he and his people are in the wrong! Indeed! But has not Pharaoh been reduced to plea-bargaining with Moses and Aaron twice before (8:8, 25–28)?

Moses’ reply is simple, confident, and noble. He will spread out his hands in prayer (a gesture of request and appeal to God) once he is back in the country with his own people, and the hail and thunder will stop—to prove once again (in this repeated apologetic and evangelistic refrain) that the whole earth belongs to the LORD. “But,” Moses adds, “I know that you and your officials still do not fear the LORD God” (v.30; an unusual combination of divine names [Yahweh-Elohim] seen only here and in seven other places in the OT besides in Ge 2 and 3; see D. F. Kidner, “Distribution of Divine Names in Jonah,” TynBul 21 [1970]: 126–28, for its use in Jnh 4:6, another Gentile context).

31–35 Even though most commentators complain about either the location of the parenthetical note in vv.31–32 (most prefer it to appear after v.25) or its alleged artless midrashic attempt to explain and harmonize later plagues with the extent of the destruction here, we find it most conveniently located. The integrity of the seasonal observation confirms the order in this text, if the narrative is taken on its own terms and allowed to be innocent until proven guilty. Accordingly, before Moses prays for the hail to cease, he has sufficient time to tell the reader just how extensive the damage has been.

Furthermore, since in Egypt flax is usually sown in the beginning of January and is in flower three weeks later, while barley is sown in August and is harvested in February, both would be exceedingly vulnerable if this plague occurred in the beginning or middle of February (probably a little later than usual with a high Nile year). Wheat and spelt (see Notes) are also sown in August but are not ready for harvest until the end of March.

That Goshen is unaffected by this storm matches the agricultural observations, for the Mediterranean temperate zone has these storms only in late spring and early autumn, but not from November to March (Hort, 48–49). Flax is used for linen garments. The vicinity of Tanis was ideal for producing it. Barley is used in the manufacture of beer (a common Egyptian drink), as horse feed, and for bread by the poorer classes.

After Moses’ prayer is answered, Pharaoh once again rescinds his offer and forgets all about his confession of sin and wrong.

NOTES

13–14 More than wordplay can be found in the divine demand, “Release my people . . . or I will release all my plagues [on you]” (NIV, “Let my people go . . . or . . . I will send”). In both instances the verb is ![]() (šlḥ).

(šlḥ).

14 For ![]() (kol-maggēppōtay, lit., “all my plagues”) the NIV has, “the full force of my plagues.” See Notes on 8:2.

(kol-maggēppōtay, lit., “all my plagues”) the NIV has, “the full force of my plagues.” See Notes on 8:2.

![]() (ʾel-libbekā, “against you”) is literally, “at [or] into your heart.” There is no need to emend the text to