Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore …

—Edgar Allan Poe, “The Raven” (1845)

Halloween, that day of symbolic horrors, seemed an appropriate time to stop. I had already stocked the refrigerator of my apartment in Bangkok’s Chinatown with nutritious, easy-to-digest food such as goat’s milk and yogurt, even though I knew it would be days before I could eat again. The flush lever on my toilet had long before rusted tight, and I’d become accustomed to lifting the lid of the water tank and pulling up on the little chain. Within a day or so that porcelain lid would be too heavy for me to lift, so I took it off and put it behind the toilet where I wouldn’t trip over it.

The door to my ninth-floor flat was situated down a dark corridor and next to a little-used stairwell that was marked as a fire escape. Like most doors in Chinatown, mine was barred against intruders with a wrought iron outer door. From inside the apartment it was possible to reach out through the bars of the outer door and fasten a large padlock on its latch, giving the impression that nobody was home. My bedroom window looked out on the corridor, and it, too, was barred. In addition to the bars, this window had layers of opacity to ensure privacy: on the inside heavy drapes, and on the outside a tinted windowpane completely obscured by a screen covered with dust so thick it might have been mistaken for a curtain of ash-colored velvet. From outside my apartment it was all but impossible to tell that I was inside.

For months I had been a recluse to the extent that my face-to-face social obligations were almost nil. But this situation was masked by the fact that I worked from home—people rarely saw me in person anyway. Communications didn’t worry me. Everybody knew that email had become my preferred method of keeping in touch. What they didn’t know was that I’d discovered email was perfect for preserving a façade of normalcy no matter how crazy things got. I could take as long as I needed to reply while fabricating plausible excuses as to why I couldn’t leave my apartment. If I became too addled to talk coherently, I could dodge telephone calls by simply ignoring them. Roxanna was the one person whose calls would be difficult to ignore, but her invitations had fallen off as my downward spiral had become more and more apparent.

As I waited for the symptoms to start, I began to think of ways to occupy my mind. I was no stranger to this scenario: I had twice tried to put a halt to my daily smoking. My first attempt might have succeeded if only I’d been more disciplined. Backing off from the habit wasn’t as difficult as I’d thought it would be, and this had made me confident that I was still my own master. But then I lost control. Two months of restrained dabbling on weekends had descended into a daily orgy of indulgence.

A second attempt at cutting back was harder, but I’d managed to abstain for a whole month before finding the perfect excuse for a relapse. And thus began my free fall. Subsequent attempts to quit were painful ordeals that lasted a single harrowing night and ended at dawn, when I would crawl back to the mat, light the lamp, and smoke with a voraciousness that shocked me. I watched as my own hands prepared pipe after pipe, both thrilled and terrified to know that a line I’d memorized from a Victorian-era book now applied to me: I had “succumbed to the fascinations of opium.”

By Halloween 2007, I had been smoking opium continuously for months—as much as thirty pipes a day. I decided to try to quit again. This time, I told myself, I would not fail. I knew I would be in for a rougher ride; I had let my habit get so out of hand that the withdrawal would be many times worse than my previous ordeals. I recalled those days of soul-piercing pain, the nights of sweat-soaked insomnia, and I tried to imagine how anything might be worse.

To steel myself for the storm, I pretended that I was going to suffer a bout of malaria in the days before quinine. The idea appealed to my sense of the romantic—here was another age-old affliction that had to be weathered stoically. But I knew very well that malarial fevers were never as ugly as what I would soon experience. Among my small library of century-old books with gilt leather bindings I had discovered a paragraph or two that described in clinical prose what I was about to endure.

I had read about the all-encompassing pain that drove opium addicts to beg for the relief that could be had only via a few draws on the pipe. I had read of people tightly trussed to their beds and locked in rooms by loved ones who then stopped their ears with raw cotton to block out the tortured screams. There were tales of prayers shrieked through the night; pleas for a hasty death that were sometimes answered by a body too shocked to function beyond a few days without opium. The morning after would be no scene of poignant demise; no Death of Chatterton angelically sprawled across his bed high above London. It would more resemble the aftermath of a cholera victim’s death throes—a room defiled by the performance of a macabre, bone-twisting Watusi to the rhythms of explosive farts and geysers of liquid shit.

And if I survived the physical pain, once it began to diminish, the mental anguish would take over: a dense boom of depression lowered onto a brain already exhausted by long nights of sleeplessness. This desperate funk manifests itself in many ways and is seemingly tailor-made to suit the fears and phobias of each and every addict. Just as your body turns against you during the days of physical withdrawal, so, too, your mind will conspire with opium to unleash mental torment at its most intolerable. Whatever is most likely to unhinge you, that is what you will experience. Imagine the sound of a thousand babies crying inconsolably for hours and hours on end. If I survived the physical pain, for how much longer would my opium-deprived brain persecute me? A month? A year?

The very thought of this had in the past been enough to make me give in before even starting. But this time I was determined. Savor what Halloween was meant to be, I told myself. Savor your nightmare. When it is all over you will be free of opium … forever.

My provisions were stocked, and the most important preparation was in place: my opium-smoking layout. Should I need it, the hardwood tray with all the necessary accoutrements meticulously arranged upon it was waiting under my coffee table in the living room, together with a bottle of the finest liquid opium. Some might think it self-defeating to have a quick fix at hand, but I was unsure of whether the accounts in those old books were exaggerated. If they weren’t, and if death was as real a possibility as the books suggested, I needed to have the antidote at the ready.

It was late evening, nearly twenty-four hours since my last pipe, when the “opium cold” began, an array of flu-like symptoms—sneezing, watery eyes, and runny nose—that announces the body’s first signs of falling to pieces. This is a common event for opium addicts, something I had many times experienced whenever I got too busy to recline and prepare some pipes—a simple reminder that opium was needed to tighten things back up. This time, the arrival of these symptoms caused me to retreat to my bedroom with its single blacked-out window. I wanted no part of the outside world. The bustling sounds of nighttime in Chinatown floated up to my flat on waves of heat emanating from the sunbaked concrete, but I had no desire to stand at a window and look at the city below. I had long before become too detached to enjoy something as worldly as a room with a view, and had hung blankets over the windows to promote the illusion of perpetual twilight.

In order to keep my mind off the steadily intensifying symptoms, I got online—YouTube—and did some searches. I looked up an old cartoon that I’d stumbled across days before while looking for Halloween fare, a Fleischer Studios gem from 1930 called Swing You Sinners! I watched the clip over and over that night until the manic jazz and snatches of menacing dialogue became imbedded deep in a part of my brain that specializes in turning catchy songs into maddening little ditties.

Spook #1: “Where you want your body sent?”

Spook #2: “Body? Ha! There ain’t gonna be no body!”

Oh, yes there would. I began to dwell on morbid visions of my corpse being discovered, the centerpiece of a room that looked as though it had been ransacked by a madman. Whoever found me would also find my collection of antique opium-smoking paraphernalia—those pieces that had survived my thrashing about like a headless chicken. There was a time when I would have died before putting my collection in peril—no exaggeration—but of late it had become just another source of convenient income: a way to pay for more opium.

At some point I lay down on my bed and fell into a fitful sleep. I woke up just before dawn on November 1—All Saints Day—with a loud buzzing in my ears and a dull headache. My immediate thoughts were recollections of nightmares: vague scenes based on long-buried memories of celebrating Todos Los Santos as a young man in Manila; images of crowds among concrete crypts in candlelit cemeteries. Those real-life events had been joyous occasions, but my dreamed version was suffused with loss and a bitter longing.

That first night without the pipe was a taste of what I was to lose: Never again would sleep be so delicious; never again would dreams be so real. The scene in the cemetery felt as though the dreams themselves were aware of their imminent demise, that without opium my dreamed events would never again enjoy as much importance as my predictable waking life. That overlap—the blurring of lines between sleep and wakefulness that I experienced with daily opium use—would soon cease to exist. I couldn’t help but feel I was giving up half my life.

Those first waking thoughts set the tone for the morning of that second day. Feelings of impending loss kept resurfacing, and all thoughts led to opium. I tried to watch movies on my laptop, but they served only to anger me. Who were these people and what did they know about life? My principal feeling toward nonsmokers was scorn. Opium arrogance kept me engaged, but just barely. I stared at the performances meant to evoke emotions such as love and loneliness but I could not relate. Watching people interact was like being forced to watch a mime—I felt as though I lacked the patience to understand the message. I had lost interest in the activities of everyone but a couple of opium-smoking friends. The rest of humanity I could ignore in the same way that one tunes out the speakers of a foreign language.

When I could no longer look at the images on my computer screen I tried to read, but this was equally difficult for my opium-starved brain. I found uniquely silly the articles in the many back issues of The New Yorker that littered my apartment. Focusing on unread pieces was impossible, and when I tried to reread articles that I’d enjoyed in the past, they now seemed insultingly dull. I could read no more than a paragraph or two before launching the magazine at the wall like a fluttering missile. If only The New Yorker were heavier, I thought to myself, I could break its spine.

As the day wore on these feelings of anger and alienation were usurped by a riotous fever. Around me the tropical city sweltered while I wrapped myself in blankets and shivered with exaggerated spasms that might have looked comical had anyone been there to witness them. Time seemed suspended, and I had unplugged the clock so I wouldn’t be tempted to look and gauge time’s progress. I do not know how long I shuddered with cold before a rising heat replaced it, drenching me with sweat and compelling me to throw the blankets to the floor. After some time had passed I frantically gathered them up again to shield myself against a bracing cold that was all in my mind. My skin was studded with pebbly goose bumps—the inspiration behind the term “cold turkey.” Despite the chill, blankets felt loathsome against my body, and when I was broiling with fever even the breeze from the electric fan made my skin crawl. I seemed to have lost the ability to enjoy even the slightest bit of comfort.

Several times that night I was visited by these brutal seasons, and then sometime before dawn I actually prayed—doubled up like some slave waiting to be fetched a cruel kick. I had never before in my life felt desperate enough to pray, but that night I did so with a fluency and sincerity that surprised me.

It must have worked. When I awoke a few hours later my pillow and bedclothes were sticky with opium-laced sweat, but the fever had mostly subsided. Feelings of celebratory relief were premature, however. What had woken me up were cramps in my stomach—gut-wrenching pains that brought me to my feet almost involuntarily and propelled me toward the bathroom. Depth bombs of shit began exploding out of me, punctuated by gas bursting into the toilet bowl. The force and noise were such that it seemed as though my bowels were bellowing angry obscenities, and I found myself answering each anal exclamation with an oral one of protest and awe: “Whoa! What the fuck?!”

So frequent were these violent purges that my strength was quickly drained, flowing down the toilet with torrents so copious that I thought my insides had liquefied. I would have sat there and waited out the waves of diarrhea had my legs and arms not become racked with cramps that demanded movement. Here it comes, I thought to myself, the beginnings of the uncontrollable thrashing that was described in old accounts—this was what might kill me. From the bathroom into the bedroom and back. How many trips had there been? Enough so that raw skin could no longer be wiped with toilet paper. I used a handheld showerhead to rinse myself clean, but the taxing cycle of constantly disrobing, washing, drying off, and getting dressed soon became too much, and so I paced my bedroom wet and naked, waiting for the return of stomach pains that again and again sent me running back to the toilet.

Then all hell broke loose. My arms and legs felt as though they were being pulled from their sockets. My guts bloated inside me, forcing up vomit followed by gobs of greenish bile. Even my testicles ached with nauseating pain. Mentally I was reduced to directing the most basic actions, trying to steer clear of walls and furniture while flailing my arms and legs about as if I were on fire.

However, there was one task at which my brain functioned as usual—that frantic tune from the old cartoon on YouTube played in my head in an endless loop. Naked, I jumped around the room to the private strains of a Harlem jazz band. Like a human pogo stick I bounced. Completely exhausted, I aimed for the bed and tried to rest and catch my breath, but I could not stay still. The opium was working its way out of my system, squeezing through the walls of every one of my cells, causing me to howl in agony and leap to my feet after lying motionless for mere seconds.

I don’t know how long I was in this state, but at some point I decided that I could go no further—and by my simply having made up my mind to give in, some of the pain instantly began to subside. But I did not renege on my decision. I heard Jean Cocteau’s advice from 1930 above the ringing in my ears: “Do not persist. Your courage is to no purpose. If you delay too long, you will no longer be able to take your equipment and roll your pipe. Smoke. Your body is waiting only for a sign.”

Hobbling to the living room on legs bruised from countless barks against furniture, I dropped to my knees and crawled toward the woven-cane mat. With hands that seemed to belong to someone else, I jerked the layout tray from under the coffee table. I scratched through several wooden matches before one lit, burning myself in the process, and needed both hands to steady the flame in order to light the opium lamp. Once that was done, I gathered all my remaining concentration to prepare a pipe.

My brain and body were on my side at this point. I felt strength return and a sharpening of mind at the mere thought of getting some opium vapors into my lungs. While preparing that first pipe I overcooked the pill—a botched job that normally I would never have carried through with, but on that day I sucked greedily at the thick white smoke and held it in my lungs while shakily beginning the preparations for my second pipe. This next one was better—the opium vaporized as it was supposed to, and the sweet vapors swirled about me as I exhaled gratefully. I rolled the third pipe with much less urgency. I even remembered to exhale through my nose to let the vapors pass along moist membranes, absorbing just a trace more opium. Every little bit counted.

“Yah dee,” I whispered to myself in Lao, repeating the words that Madame Tui used to pronounce over my supine body after her pipes had done their work. “Good medicine.”

Indeed. Closing my eyes for a moment I savored a miracle: the total banishment of pain. The vacuum was instantly replaced by a deliciously tingling wave that crept up the base of my neck and caressed my head with something akin to a divine massage. Whereas moments before my muscles had felt like they were being pinched by countless angry crabs, there now was a soothing sensation of calm and well-being. I prepared one more pipe—this time with almost no shakiness—and held the vapors deep in my lungs before exhaling slowly through my nose.

With the torment quickly fading from memory, I noticed my naked and disheveled state. I rose from the mat with restored agility and calmly went into the bathroom to take a leisurely, hot shower, washing away the oily sweat and traces of vomit, mucus, and feces that covered my skin and clotted my hair. Refreshed, I dried and dressed for comfort in a clean cotton sarong and a linen guayabera before returning to the mat and reclining once more.

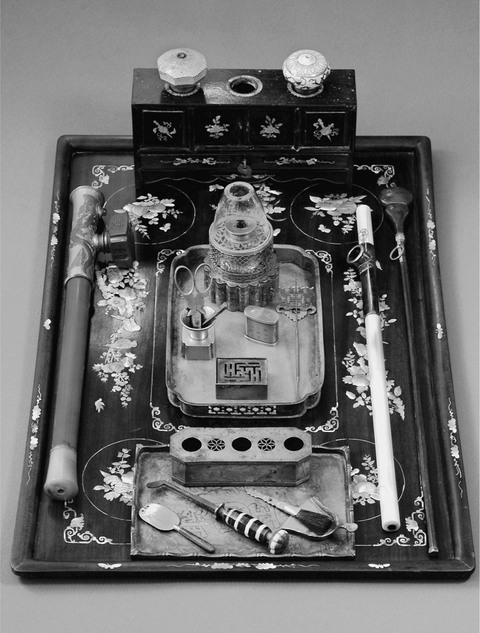

I took a moment to admire my opium-smoking layout, a collection of rare and elegant paraphernalia that took years to gather and was worth thousands of dollars. Equal parts Asian artistry and steampunk science, like props from a scene concocted by a Chinese Jules Verne, the heavy nickel accoutrements waited on the wooden tray before me. There were picks and awls of obscure provenance, reminiscent of antiquated dentists’ tools; odd brass receptacles resembling miniature spittoons; pewter containers lidded with delicate brass openwork; tiny scissors with gracefully looping handles; dainty tweezers adorned with ancient symbolism denoting luck and wealth and longevity; strange implements with handles of ivory and blades of iron resting on a small brass tray etched with a detailed depiction of a young scribe offering tea to a robed mandarin. There was a tiny nickel-handled horsehair brush and a matching pan for sweeping up bits of ash. Enveloping everything was the warm glow of the opium lamp, the shining centerpiece of the layout tray. Second only to the pipe in importance, my oil lamp had a bubble-flecked glass chimney shaped like a fluted dome.

The crowning glory of my entire layout was perched lightly upon the chimney of the lamp: a hammered silver lamp shade in the form of a cicada. Slivers of lamplight shone through filigree work in the insect’s abdomen and—most magically—illuminated its red ruby eyes.

Lying on my back with my head propped upon a porcelain pillow, I hefted the opium pipe in my left hand like a gun, my index finger curled around its silver fittings as though on a trigger. The Chinese word for opium pipe translates to “smoking-gun,” and this one had just killed all my pain. With my right hand I lifted a tiny copper wok by its ivory handle and placed it upon the opium lamp. I measured five drops of opium into it. Within seconds the small pool of liquor began to boil and its heady sizzling was all I could hear.

Once again I was the alchemist, the one who had rediscovered how to work these long-forgotten implements. I was one of just a handful alive who could manipulate the elixir in the old Chinese manner and create bliss-inducing vapors. I was a high priest, one of the last still vested with the powers to perform these mysterious rites. After years of patience and persistence I had relearned the ancient craft and brought these hallowed rituals back from near extinction. This exclusivity of knowledge—watching my own deft hands use esoteric accoutrements to work a rare vintage of opium—gave me as much joy as the narcotic itself.

Complete layout of paraphernalia for opium smoking from the author’s collection. The components date to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and were crafted in China. (Photograph by Paul Lakatos)

As I began cooking and rolling another pill for the pipe, I smiled to myself as though amused by the foolish antics of a young child. “Why on earth did you put yourself through all that?” I said aloud.

It had been barely thirty-six hours since I had begun my last attempt to quit on my own. Of course opium had won. Opium always won.