Unlike other forms of the opium-habit, that by smoking finds a special inducement in companionship, especially if the companions are congenial.

—H. H. Kane, Opium-Smoking in America and China (1882)

Over time, I met more aficionados of opium-smoking paraphernalia, and as my online auction bonanza continued, I was able to quickly and economically build a collection that was the envy of our tiny community. Nearly all the collectors that I got to know concentrated on acquiring opium pipes and lamps, giving little thought to the other pieces of paraphernalia that had been devised to make opium smoking convenient. I began to turn my attention to these mysterious tools of the habit.

While doing guidebook research in Laos, I spent many more hours reclining at Mister Kay’s opium den. Madame Tui’s had since closed. The sight of vomiting backpackers moonwalking around Vientiane eventually caused the police to pay her a visit, and from then on she smoked alone. However, nothing changed at Mister Kay’s, except that my visits were not frequent enough to keep his teenaged grandson from challenging me at the door. Luckily the proprietor and regular smokers always remembered me from the times I had arrived bearing pieces of paraphernalia whose function was a mystery to me. Sometimes the skeletal old smokers would coo in amazement. “Haven’t seen one of those in a long time!” they whistled through the stumps in their gums before giving me a demonstration of how the implement was used.

Mister Kay’s was invaluable to me. It was the one and only place where I might learn some rare piece of opium knowledge that was otherwise lost to history. The implications of this affected me deeply. This room and its ancient habitués smoking adulterated opium with jerry-rigged paraphernalia was the last remnant of what had only a century before been a worldwide, multimillion-dollar industry. Opium smoking, a habit that had financed empires and made fortunes all over the world, was now so rare that only in this landlocked backwater could the classic Chinese vice be witnessed. Imagine the possibility that, a mere hundred years from now, the modern wine industry and the millions of people who support it could be reduced to a roomful of elderly winos swilling fortified wine from stemware held together by packing tape. This is how thoroughly opium smoking has been eradicated.

At about the same time that Mister Kay’s was becoming my research lab, I again ran across the scrap of paper on which I’d written down the contact information for that friend of the author Peter Lee. Coincidentally, this person who Lee claimed could teach me much about opium smoking was based in Vientiane, so I made it a priority to contact him before my next trip to Laos.

This was how I found Wilhelm Borunoff. An expatriate Austrian who had lived in Southeast Asia since the 1980s, Willi claimed to be the progeny of Russian nobility and a long line of artists—a history that his broad Slavic forehead and precise taste in clothing seemed to confirm. He had lived in Bangkok for nearly a decade before relocating to Vientiane after the Soviets withdrew from Laos in 1991. Willi’s plan was to revive a Lao coffee industry that had been established by the French before World War II, but which had all but died as a result of wars and bad politics. He had built a small coffee bean roasting facility and was one of a handful of pioneering entrepreneurs who were testing the waters of the country’s fledgling market economy. When I met Willi in 2002, he was battling corrupt Lao officials to hang on to his coffee investment. “It’s crazy,” he explained as he gave me a tour of his operation. “Every day some new team of officials shows up to inspect and then demands a fat bribe to let me continue. I thought Bangkok was corrupt, but this place makes it look like a colony of Shakers.”

Things did not look good, but that didn’t stop Willi from treating me to his impeccable brand of hospitality. His home was a teakwood bungalow in a bamboo grove on the outskirts of Vientiane. The bungalow, which Willi shared with his Thai-Chinese wife, had been built using aspects of Western and Southeast Asian design, and the open spaces within suggested some tribal longhouse, with a kitchen, dining area, and room for relaxing and receiving guests situated in a row. Off the living room was a wide verandah where Willi spent long mornings sipping oolong tea and contemplating a Zen garden that he had planted below. Under the house was a basement he told me was used for storage, and behind it was a wooden pavilion built up over the edge of a lotus pond.

Willi had decorated the house with objects that he’d collected all over Asia, but with an emphasis on Chinese tea-drinking accoutrements—wood and glass display cases were filled with diminutive teapots fashioned from Yixing clay. Taking in the room on that first visit, I soon spotted a bamboo opium pipe whose saddle was adorned in the Yunnanese style with a row of semiprecious stones. A mutual friend had told me that Willi owned two antique opium pipes, and when I emailed him I used this as an excuse to propose a visit, expressing an interest in photographing them.

After I had examined the pipes, Willi invited me to join him for tea on the verandah. I was interested to know if he had had any experience with smoking opium, but Willi was prudently guarded on the subject. He admitted to having smoked in the hills with the Hmong years before, and only after I had related tales of my trips to the rustic Vientiane dens did his enthusiasm get the better of him and he began to tell some stories of his own.

“When I first came to Vientiane there were still a few members of the Corsican mob who had controlled the opium trade in Indochina before the Communists took over,” he told me. “One ran a restaurant called Erawan down near Kilometer Three.” Erawan is a three-headed elephant, the Lao name for the mount of the Hindu god Indra, and the symbol of the Lao monarchy. “That crazy Corsican managed to stay in Laos after the revolution, and somehow the Communists let him keep the restaurant and never even made him change its name. He’s gone now. His half-Lao son got involved in heroin and committed suicide right there in front of the restaurant.”

Willi claimed to have learned English as a young man in New York City while working for an old European Jew whose Yiddish accent Willi had absorbed and could turn on and off at will, an affectation that gave a playful yet cynical tone to his stories. Willi knew Mister Kay but scrunched his nose in mock disgust when I suggested that we visit the den together. “Oy! Dross smokers!” he snorted.

Later that evening, after the sun had set, I came to understand the significance of that remark. We talked far beyond the hour that I had expected the visit to last, and Willi asked me to stay for dinner. After the meal he said he had something to show me. Willi led me to the basement, and there a modest opium layout tray was being assembled by an old Vietnamese manservant dressed in what was once the fashion of the Chinese in Southeast Asia: a mandarin-collar shirt and baggy trousers that were a matching color of indigo. The layout tray was set down on a mat spread out on the concrete floor between crates and boxes in the basement storage room. I could tell by the servant’s fluency in arranging the utensils on the tray that this was not the first time he had performed the duty.

Willi and I wordlessly smiled at each other as the servant lit the diminutive lamp and then bowed out of the room. As always when I was about to smoke opium I felt gripped by a giddy excitement, and I could tell that Willi felt the same. Without having to be told, I also knew that he was bestowing upon me a grand honor that he rarely extended to others. I could sense in Willi’s actions a restrained graciousness that said he did not take the act of opium smoking lightly, and would not have invited me to share a pipe had he thought I wouldn’t appreciate the experience.

Willi and I positioned ourselves on the mat, reclining on either side of the tray and facing each other over it. He produced a small brown bottle with a dropper, unscrewed the lid, and invited me to sniff the contents. It was opium, but in liquid form and with a surprisingly complex bouquet, as though it had fermented—it smelled something like loam drenched with red wine. He placed a few drops in a miniature copper wok perched on the opium lamp’s chimney, and as the liquid began to sizzle and evaporate, a rich scent filled the air—like roasted peanuts but with a hint of animal musk.

“Picasso once said that opium is the world’s most intelligent smell,” Willi remarked while holding a skewer-like opium needle at the ready and without taking his eyes off the boiling opium. “Or perhaps he said it’s the world’s least stupid smell,” he continued as he brushed the now gummy opium from the wok with the tip of the needle. “I’ve seen the remark quoted both ways in English. I need to find it in the original French. Depending on what Picasso really said, it’s either a compliment to opium’s uniqueness or a comment on Picasso’s jadedness.”

Willi looked at me over the tray and held my eyes, and I realized that I hadn’t acknowledged his remark. I was hardly listening. Instead I was mesmerized by what I had been witnessing. Still reclining next to the tray, Willi was deftly “rolling”—the complex process of preparing a dose of opium for the pipe. It was the first time I had ever seen a non-Asian prepare opium—and he did so with unparalleled grace.

Willi’s accoutrements were few, simple, and unadorned—similar to what I had seen being used in the opium dens of Vientiane—but the quality of opium that he had somehow obtained was like nothing I had ever experienced. Here finally I would taste chandu, that rarefied form of smoking opium I had only read about in old books. Chandu, a Malay word that originated with the Hindi candū,, was once the preferred poison of sophisticated opium smokers from Peking to Paris. Chandu of this grade had not been produced for decades, simply because there was no longer any demand for high-quality smoking opium.

The acres of opium poppies being cultivated in Afghanistan and Burma invariably supply clandestine heroin refineries whose deadly but lucrative product is then sent all over the world. Such operations are, of course, carefully guarded at all stages. In the case of Burma, much of the opium under cultivation is watched over by the Wa, a fierce tribal people whose head-hunting made them the bane of the British during the colonial era. In modern times the Wa have traded in their spears and long knives for Chinese-made Kalashnikovs, hiring themselves out to fill the ranks of the private armies of Burma’s drug-lord generals.

Obtaining raw opium in large enough quantities to produce chandu is dangerous and thus expensive. If someone could manage to buy enough raw opium—and if that opium were real and reasonably pure—then there was the task of boiling and filtering the crude sap, followed by hours of allowing the concoction to settle before more filtering and settling. A dash of some fragrant liqueur would be added to the elixir to kill spores that could cause mold, and the chandu would then be sealed up in earthenware jars capped with beeswax and allowed to age.

Willi paid dearly to obtain genuine and pure raw opium, I would learn, and then did this refining himself using a collection of copper pots, his process constantly evolving as he experimented with new techniques. Meeting Willi was for me like discovering the key that opened the long-locked door to a room full of knowledge. How many people remained in the world who, in the twenty-first century, could obtain good opium in the quantities needed to produce premium chandu, and who were then able to prepare and smoke that chandu in the classic Chinese manner? I was convinced that Willi was one of the last of an all but extinct breed.

The effects of opium intoxication—the quality of the high—depend on the quality and purity of the blend being smoked. In the drug’s heyday, raw opium arriving in China passed through a series of brokers and merchants who had methods of diluting it in order to maximize profits. The easiest and most effective way was to add a quantity of boiled dross. Because of the high morphine content found in dross, adding it to opium changed the nature of the high. The more dross added, the more stupefying the intoxication.

The poorest users smoked pure dross, which is why descriptions in travelers’ accounts of the lowliest opium dens in old China inevitably feature cramped rooms full of seemingly comatose opium smokers lying about in various stages of mental and physical decay. By contrast, Willi’s chandu was enlightening, markedly different from what I had previously experienced while smoking the dross-laced opium on offer in the dens of Vientiane.

How did it feel? Physically, opium was energy. A few pipes and I was enveloped in an electric skin. As time passed after the initial pipes were smoked, the intensity of the high waxed and waned depending on such matters as whether I was lying down or sitting up, or whether my eyes were open or closed. Unlike the opium I had smoked previously, Willi’s chandu allowed me to move about without any loss of physical coordination—there was no staggering or moonwalking. I also noted that throughout the session, Willi’s meticulous rolling never faltered.

Mentally, opium was a welling euphoria followed by a serene sense of well-being. The effects of the chandu were gradual and subtle, washing over me like a succession of tender caresses. A juvenile lust for kicks would not likely be satisfied by chandu’s leisurely and deliciously nuanced mental banquet. This perhaps explains why, in China’s past, high-quality opium was considered an intellectual pursuit and not recommended for young people or the mentally immature.

Contrary to opium’s popular reputation, my own experiences indicated that the drug was not hallucinatory. Rudyard Kipling’s short story “The Gate of the Hundred Sorrows” (1884) features an opium addict who watches two dragons on a brocaded pillow become animated and begin dueling as the character smokes pipe after pipe. A memorable scene perhaps, but Kipling’s portrayal strikes me as the fantasies of someone who had no firsthand experience.

The so-called opium dreams—at least in the primary stages of opium use—are not waking dreams or hallucinations. In fact, a bit of vintage slang still in use today best illustrates opium’s most prominent mental kick: “pipe dream.” This term meant the same then as it does today, a way of describing an irrational sense of optimism. Irrational or not, this is opium’s greatest gift to the smoker: boundless optimism—the kind that one rarely experiences beyond childhood. All good things seem possible; problems are easily solvable; obstacles are always surmountable.

For me, smoking opium in those early, heady days of experimentation was like donning a custom-made pair of rose-tinted glasses. Besides the optimism, a few pipes made me feel as though I could recapture a childlike wonder at the world. I also felt a renewed sense of excitement—again, the pure emotions from childhood. Yet these feelings of wonder and excitement were applied to an adult’s sophisticated sense of appreciation. Watching a dragonfly hover above the jade-hued surface of the lotus pond behind Willi’s house was not merely captivating but joy-inducing. Opium did not alter the landscape; it merely made me wondrously aware of the world’s beauty, giving me the sense that I was seeing it all for the first time. Transported to such a place, who needed dueling dragons on pillows?

Sometime during that first session I had an idea. Willi had access to a grade of opium that was all but impossible to find and, even more important, a safe place in which to enjoy it. I had in my collection pieces of paraphernalia that were of an opulence and richness that could no longer be reproduced. Some were missionaries’ trophies and had never been used. Although more than a century old, these pieces were in near pristine condition. What if Willi and I were to combine these rare aspects of opium smoking—his incomparable chandu and my antique paraphernalia?

Over the next few years that is precisely what we did. Our goal was to put together a layout tray with all the requisite pieces that, when finished, would comprise dozens of rare items crafted specifically to assist in the ingestion of opium. It would be a complete layout the likes of which hadn’t been seen since the People’s Liberation Army marched into Shanghai. The pieces of paraphernalia would, of course, have to match, and that was the real challenge: to find accoutrements that matched as closely as possible and assemble them into a stunning whole.

Visiting Willi once a month, I would take the night train from Bangkok and disembark in the cool of the morning, transferring to a bus in order to cross the bridge over the Mekong River into Laos. With each trip I brought with me a rare piece of antique opium paraphernalia, having spent the time between visits feverishly seeking the next piece. My research would begin with my photo archive—a part of which was devoted to historical photographs of opium smokers.

Images of people smoking opium are not exactly plentiful. By the time photography was invented there was a social stigma attached to the vice even in those places where the drug was not illegal. The photographs that do exist can be divided into two groups: people smoking opium and people simply posing and pretending to smoke. As usually happens in life, the posers were easier to find, but fortunately they were also very useful to me.

With the boom in popularity of postcards in the early 1900s, photographers began looking for subjects that would sell. In places where opium was known to be smoked, a postcard depicting the act was a popular souvenir with visitors. China was, of course, known for its prodigious opium consumption, but going into an opium den or the smoking room of a private residence and taking a photograph was usually out of the question.

To solve the matter, photographers in cities such as Hong Kong and Shanghai re-created such scenes in their own studios, complete with layout trays and at least two smokers posing on either side. Sometimes the scene included an elaborate set of hardwood furniture—including an opium bed, a pair of stools, and perhaps a chair or two—and a party of Chinese onlookers waiting their turn at the pipe. Despite the fact that the subjects were merely going through the motions, the images were important to me for the lavish paraphernalia on display. If I scanned and enlarged the images I could sometimes obtain a clear view of complete opium layouts with all the accoutrements beautifully arranged in the symmetrical way that was so popular among the Chinese.

Photos of people actually smoking opium are rare—especially those captured in China. More common are photographs of people indulging in the vice in French Indochina and the United States. Some of the postcard images from France’s Southeast Asian colony look to have been taken in studios, albeit with smokers actually in the act of smoking. Others are in rustic settings that suggest the photographers searched villages or the “native quarters” of towns until they found a smoker willing to pose with his layout.

In San Francisco’s Chinatown there were dozens of photographs taken, including a handful of images that were reproduced thousands of times on postcards. These, too, look as though the subjects were actually smoking, and there are even photos dating to the late nineteenth century that seem to have been taken on the sly—the photographer sneaking into a dimly lit opium den before tripping the shutter, igniting the flash powder, and then fleeing the scene.

While these more genuine depictions are probably more important historically, most were of little use to me because the smokers captured were poor and had paraphernalia that reflected their poverty. As in China, it would have been all but impossible for a photographer to gain access to an upscale opium den or a private smoking room in San Francisco’s Chinatown. A notable exception that I found and was able to study was a unique portrait taken in 1886 by famed California photographer I. W. Taber. The photo shows two Chinese men smoking opium in what looks to be a lavish room just for that purpose, complete with an ornately carved hardwood opium bed and a layout tray inlaid with mother-of-pearl.

So with the help of my selection of photos, all scanned, enlarged, and cropped, I made a list of what pieces of paraphernalia I would need and then set out to find them. In searching for these tools I had even more of a challenge than I did in looking for opium pipes and lamps. Because the uses of most of the smaller pieces of paraphernalia had been long forgotten, antiques dealers—even the ones who sold the occasional opium pipe or lamp—never carried them in their shops. Merchants are wary of buying something they might have trouble reselling, and knowing nothing about an item is good reason not to invest in it. I showed pictures to the shopkeepers in Bangkok, all of whom got their antiques from hunters roving around China and Southeast Asia. None showed much enthusiasm for passing on a search order to their hunters. I couldn’t really blame them—I was the only customer interested, and if by chance the hunters brought back some item that I didn’t want, the antiques dealers would likely be stuck with it.

Opium smokers in an opulent private smoking room in San Francisco’s Chinatown, photographed by I. W. Taber in 1886. These men are reclining on a “bed” especially made for the purpose of opium smoking. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California)

The online auction sites were my next stop. There I found much the same problem that I had with the Bangkok antiques shops—how would a seller list something if he or she didn’t know what it was? Adopting the tactic I had used to find antique opium pipes and lamps on eBay, I thought up a series of searches designed to ferret out any opium paraphernalia that had been misidentified.

My success was limited, but I did manage to find a bowl scraper with a water-buffalo horn handle and iron blade (in Chicago, listed as a “Japanese tool”), a pewter dross box with an openwork brass lid that spelled out the characters for “double happiness” (in Washington State, listed as a “cricket cage”), and a paktong needle rest in the likeness of one of the auspicious Hoho Twins reclining on his belly (in California, listed as a “chopstick rest”).

The problem was that my searches were time consuming, and they turned up maybe one piece of arcane paraphernalia a month. It was a slow way to build a collection—especially since I wanted accoutrements that matched as closely as possible so that the finished layout would look as though each piece had been crafted specifically for it. I needed a better system.

By chance while doing my online searches I ran across a seller based in Beijing who had an opium-needle cleaner on offer but didn’t know what it was, labeling it a “scholar tool.” I decided to email him with a wish list in the hopes that he could find other pieces of paraphernalia to sell me.

It was a calculated risk. I had already tried this approach with dealers in China and gotten less than satisfactory results. Once, I spent a week getting to know a merchant in Hong Kong via email who had listed an opium lamp on eBay. He said he was open to looking for more lamps for me, and I emailed him photographs of lamps from my collection to educate him about how opium lamps differed from other types of oil lamps. The merchant soon began to find opium lamps, but the prices he attached to them for resale were way beyond my means. I managed to haggle his prices down a bit and bought the best ones.

The merchant then asked me to be patient and said he would contact his dealer friends on the mainland to see if they could source more opium lamps. I thought I might start acquiring some decent items through this network, but when the merchant finally emailed photos of opium lamps he claimed to have found in China, I was surprised to see that they were all fakes whose designs were based on my own lamps—the ones in the photos I had sent him. It had taken the Hong Kong merchant mere weeks to have the reproductions made, and although I had managed to spot them, they were very good fakes. The thought was frightening.

The experience was an education, and I was to learn over time that antiques merchants in China are a particularly shrewd breed. My dealings with them seemed to follow a familiar arc: I would buy a couple of items from a merchant, and he or she would, in turn, look for more to sell me. Because there were so few authentic opium artifacts out there, the pickings soon got slim and the merchant looked for ways to cheat, substituting pastiches or out-and-out fakes. Once this began to happen, it was time to look for a new dealer.

Despite the hassles, it made sense that China would be the best place to look for the lesser-known bits of paraphernalia that I would need to build a complete working layout. More people had smoked opium there, percentage-wise and in sheer numbers, than anywhere else in the world, and the huge quantity of paraphernalia once in use there surely meant that many of these items would have escaped the bonfires of the eradication campaigns. It also stood to reason that officials in charge would have focused on destroying the easily recognizable opium pipes and lamps, and that the esoteric tools I was looking for were more likely to have survived.

Traveling to China to hunt for paraphernalia might seem like a logical move, but I knew from my forays in the antiques shops in the cities of Southeast Asia—the vast majority of which are owned by ethnic Chinese—that antiques hunting in China would be a slog, and a really expensive one at that. Shopping for Chinese antiques is a ritualized process, and not being Chinese is a distinct disadvantage. Most antiques merchants there are older men who have been in the business for years and consider themselves experts in their field. The thought that a non-Chinese might be able to discern or even appreciate the finer points of their art is laughable to them. Too many tourists have walked into their shops and balked at the prices of their treasures; too many others have allowed themselves to be fleeced. So it should come as no surprise that a non-Chinese customer walking in for the first time will be shown the worst items on offer, not the best. To get past this takes time. Assuming the proprietor will talk to you (I have set foot in Chinese antiques shops and been pointedly ignored), you must convince him that you are worthy of his time. Dress is important. The instant you walk in he will look you over and decide whether you are worth talking to. His ultimate goal is to make lots of money, and if you dress as though you have little, the proprietor will treat you accordingly.

If you manage to catch the merchant’s attention you will need to present yourself in a way that lets him know you are not a rube. It is a very good sign if he offers you tea. Sip it slowly and talk for a while of matters totally unrelated to the reason you are there. If there happens to be a piece of opium paraphernalia on display, an old lamp or pipe, ignore the item until sufficient pleasantries have been exchanged. After complimenting a few unrelated items, let your eyes rest on the piece of paraphernalia and inquire about it. Never be in a rush to ask its price, no matter how much you want it. Instead, get a sense of how much he knows about it and if he has more stashed out of sight. Often it takes more than one trip to get such information, so imagine the investment of time and money involved in going to China and following this routine at each and every antiques shop.

Shopping online still seemed to me a way to more quickly and efficiently get at what I was looking for. I had developed an eye for spotting fakes, pastiches, and extensive repair work so I wasn’t put off by the idea of buying without examining items in person. All I needed was a dealer in China whom I could trust not to bolt with my information and use it to mass-produce fakes.

I decided to try my luck with the guy in Beijing who had listed the “scholar tool” on eBay. Immediately after my initial email to him I got a reply. As eBay is loath for its users to do, we began a relationship outside of the site’s confines. The seller went by the name Alex and had only recently begun selling online. Alex was my age and had been trading in Chinese antiques on a small scale for a couple of years. He had no shop but instead had set himself up as a middleman—buying antiques at flea markets and then reselling to the owners of Beijing’s high-end antiques shops.

At first I was reluctant to let Alex know the real use for his “scholar tool,” but it soon became apparent that if I was unwilling to trust him with my knowledge there would be a real limit on what he could do for me. I proposed a trade—an education for the opportunity to have the first look at anything he found. I would also supply the contact information for a handful of other collectors who I knew would be interested in buying the items I had passed on. I was fortunate that Alex saw the opportunity for what it was—a way for him to corner the market before anyone else in China knew that a market even existed, giving him an advantage over all the other hunters and dealers who were out there looking for the next big collectible.

Over two years I fed Alex a steady stream of photos and requests. Once he had scoured Beijing’s flea markets and sidewalk stalls, he began making trips to explore other cities. The result was a bountiful harvest that wildly exceeded my expectations. Alex took a keen interest in the workings of the paraphernalia and its ornamentation, and seemed genuinely excited whenever he discovered a particularly well-crafted item. Unlike other Chinese merchants I had dealt with, he never feigned excitement in order to justify slapping exorbitant prices on his finds. No matter what Alex discovered, his prices always remained fair. With his help, I was able to acquire those pieces of paraphernalia that I’d previously seen only in historical photographs, and the complete working layout that Willi and I had dreamed of assembling became a reality.

Willi and I liked to think of ourselves as heirs to the lifestyle of wealthy, old-time smokers whose only limitations were their own imaginations. Not content with a single opium pipe, we amassed a small selection of pipes to choose from, each a favorite because of some unique detail in its design or ornamentation. Some were the aforementioned spoils of missionaries, long unused but finally put to the test by the two of us.

One pipe had once belonged to a Lao prince, its stem of knotty wood and mouthpiece of polished horn so heavily impregnated with opium resins that you might think they were carved from stone. Another cherished pipe was a standard model of which there had once been millions. Its mottled bamboo stem came from the forests of China’s Hunan Province. The stem was fitted with ivory end pieces—de rigueur on all but the most modest pipes—and on the paktong saddle was the pipe’s only adornment: a fiery red stone whose color was the yang meant to balance out the yin of the opium being smoked.

One of our pipes was of recent manufacture. Madame Tui’s husband, Vientiane’s maker of opium pipes, had apprenticed his only son to the craft at the age of thirteen. The old pipe maker had died in the late 1990s, but by that time he had also passed on his Vietnamese love for chased-silver depictions of muscular dragons to his son, Kai. By chance I met Kai, by then in his thirties, during a visit to Vientiane after the city’s opium dens had been shut down in 2002. Since their closure he had carried on as a silversmith, busying himself making jewelry and a few reproduction opium pipes for tourists.

A rare opportunity became clear to me as Kai told me his father’s story. The old pipe maker had learned his craft from an elderly Chinese who’d fled to Hanoi, in what was then French Indochina, just before the 1949 Communist victory in China. Less than a decade later, both men found themselves living under another opium-hostile Communist state—this time Ho Chi Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Madame Tui and her husband fled to Laos, then still a Buddhist kingdom, and set up shop in Vientiane. It was the right choice, given the country’s tolerance of the vice outlasted everyplace else on earth—the old pipe maker was able to carry on with his trade until shortly before his death.

By the end of Kai’s story I realized who I had standing in front of me: a classically trained opium pipe maker whose techniques were based on knowledge stretching all the way back to pre-Communist China. He was perhaps the very last of his kind, and there he was making trinkets for tourists! I asked him if I could commission the finest opium pipe he was capable of making. Kai was more than open to the idea of crafting a custom-made opium pipe—it clearly excited him. He had been using substandard materials—substituting brass for silver—to make cheap pipes for tourists because the relatively pricy examples that he had produced based on his father’s teachings sat unsold on the shelves of Vientiane’s souvenir shops. I asked Kai how much he would charge for his best work, and he estimated a price of no more than $200.

My self-designed pipe took nearly a year to finish. After finding a suitable piece of bamboo in the jungle, Kai had to cure the stem to ensure it would not split—a process that in itself took many months—before fashioning the silver fittings to my specifications. Ivory end pieces were essential but, of course, using new elephant tusks was out of the question. Instead, I picked through the antiques shops of Bangkok, Penang, and Singapore until I happened upon the perfect mouthpiece: It was a five-inch length of ivory that had begun its life as a sword handle. At some time in the distant past it had been detached from its blade and a hole had been carefully drilled through its center so the ivory handle could be used as an opium pipe’s mouthpiece. The idea was rather ghoulish—had the sword ever been used to kill anyone?—but my fondness for the rich, amber-colored patina of the ivory outweighed any qualms I had about inhaling opium vapors through it.

I took the ivory to Vientiane and left it with Kai along with hand-drawn schematics of what I felt would be the perfectly balanced pipe. When finally finished, the pipe would have a blond bamboo stem with silver fittings featuring painstakingly hammered motifs that included stalks of bamboo and lush leaves. It took several trips and many modifications before the pipe was right—Kai had never undertaken the crafting of a pipe of such expense and seemed anxious he might make an error that would ruin it. When he reached a step about which he had questions, there was no choice but to put the project away until I had the time to go to Vientiane and have a look. This was, of course, not a problem—every three months I had to leave Thailand and get a fresh tourist visa.

Once the pipe was completed I gave it a name: the “Dream Stick”—an American slang term dating to the Roaring Twenties. The Dream Stick was one of six pipes from which Willi and I could choose at the start of each session—always after much enthusiastic deliberation over the merits of each pipe. I was drawn to the most ornate pipes, but Willi preferred the more streamlined examples. Usually, however, the pipe that needed the least amount of preparatory maintenance won out. Here I discovered yet another reason why opium smoking was relatively easy to eradicate: Opium pipes required constant and meticulous upkeep. They expanded and contracted with rising and falling temperatures and humidity. Pipes were mixed media, made up of parts crafted from different materials—bamboo, ivory, silver, paktong, clay—and these parts reacted differently to the surrounding atmosphere. Because of this, they always needed an inspection and some minor repairs before each smoking session. Most important, opium pipes had to be airtight before they could be used—if not, the complex vaporization process would not work.

Of all the pipe’s parts, the distinctive ceramic bowl was the most crucial to this process. Functional pipe bowls were also the most difficult items for me to acquire. I would look at hundreds before I found one that was still in good enough condition to actually use for smoking. Usually the tiny needle hole had widened during the countless times in the past that opium needles had been thrust into it. This widening, almost imperceptible to the untrained eye, meant that precious chandu would be wasted during smoking—making the bowl useless.

Fortunately I found a pair of pipe bowls on eBay that were at least a century old, unused, and still in their original box. Made from Yixing, the porous clay prized by Chinese as the perfect material for teapots, the bowls were part of a cache of opium paraphernalia discovered behind a false wall in a store in Vancouver’s old Chinatown—no doubt illicit inventory that was to have been smuggled into the United States. I paid twenty-five dollars for the pair of bowls on eBay. The seller knew what they were, listing them correctly as opium pipe bowls but foolishly giving prospective buyers a “buy-it-now” option. Were there others who would have bid on these relics? Perhaps, but according to the counter at the bottom of the webpage, I was the first to view the lot. I bought them immediately. To me these pristine bowls were priceless—I would have happily paid ten times that price.

Normally, if I came across something extraordinary online, I would email Willi a link, but this time I waited to tell him anything until the pipe bowls had arrived in Bangkok by airmail. I photographed the pair still in their original box, and emailed the image with a simple note confirming that they were in my possession. Almost immediately the telephone rang and Willi exclaimed over the line, “You must come up at once! Please stop whatever you are doing and board the train now!”

It was exactly the response I was hoping for. I will never forget the feeling of excitement as I arrived after a night on the train. I was carrying the small cardboard box enveloped in a bolt of silk, and Willi and I unwrapped and examined the bowls with the deliberation and respect befitting such prized objects. Willi selected one of them and then we readied it for use with one of the trophy pipes that had belonged to a China-based Christian missionary. After a century suspended in time, this pipe bowl would be used as the artisan who crafted it had originally intended.

The scene that day reminded me of a Jacques Cousteau program that I had watched on television as a child. The underwater archaeologists had found a cache of centuries-old wine cradled in some shipwreck and, being Frenchmen, they brought the bottles aboard the Calypso and drunk their contents with gusto. Willi and I inhaled the first pills of opium through our newly acquired relic with the same enthusiasm. The pipe bowl performed as though it were rewarding us for our efforts in bringing it to life. There were no burned pills that night, and not a single drop of chandu was wasted. After smoking his tenth pill, Willi exhaled a column of near invisible vapors toward the ceiling and fixed me with an impish grin and a gleam in his eyes that told me his next utterance would be inflected with Yiddish. Even in the dim lamplight I could see that his pupils were dots as tiny as the eyes of a shrimp. He smacked his lips with satisfaction and lisped, “Isssss qvality!”

“There’s nothing like a complete opium set to grab peoples’ attention,” an old German who ran a high-end antiques shop in the River City mall once told me. “I one time had a full opium set on a tray in my display window, and I watched the people walking past my shop stop suddenly to point and stare.”

Opium pipes are the old masters of opium antiques collecting. Pipes have broad appeal and are more readily recognized and appreciated by noncollectors than lamps and other accoutrements. But nothing impresses like a complete layout, especially one as opulent as Willi and I had assembled. In all, there were nearly two dozen separate pieces of paraphernalia on our tray. Each item was crafted from either brass, copper, paktong, or a combination of the three metals, and kept polished to a high shine by Willi’s servant. Many of our pieces were meticulously decorated with delicate openwork that an artisan had cut into the metal with the tiniest of saw blades.

Because Buddhism was important in old China, swastikas were a common motif adorning Chinese artworks—and opium paraphernalia was no exception. The swastika is an ancient Hindu and Buddhist symbol, and for the Chinese and other Buddhist cultures, the swastika carries none of the dark historical associations that it does for most Westerners. I had been so long in Asia, and had so many times seen the swastika as a decorative component of these religions—as adornment on Buddhist temples as well as on Indian, Chinese, and Vietnamese art—that Nazi associations no longer sprang to mind upon seeing swastikas in this context. So I decided not to shun paraphernalia with the ubiquitous swastika but instead to celebrate the symbol as adherents of Hinduism and Buddhism have for millennia. By doing so I felt I was taking back this mysterious spiritual motif from the monsters who had so recently hijacked it.

The opium lamp that Willi and I used was a model from China’s Yunnan Province. Minute openwork had been cut into its octagonal base of tricolored metals, allowing air to feed the flame while providing hundreds of facets on which the glow of the lamp could reflect. Although the light produced by the lamp was feeble, when coupled with the effects of a few pipes of opium, its reflection upon the layout’s gleaming surfaces seemed to tickle my eyelashes like a faint breeze.

Our lamp was fitted with cotton wick that I had sourced at a shop in Bangkok’s Chinatown. At the start of each session, Willi would push its long tail deep into the lamp’s reservoir, which he kept filled with a fragrant brand of coconut oil from India. Then he would fastidiously trim the wick with a dainty pair of brass scissors—barely two inches in length—that had been specially made for the task. He used a matching pair of tweezers to gently advance the wick when necessary. Both tools were kept in a deep brass tray that supported the lamp and contained any oil that might be spilled while filling it. Also on this deep tray was the miniature wok for evaporating the liquid chandu as well as various tools to assist with the rolling process.

The lamp tray sat centered on a much larger brass layout tray that was crowded with engraved brass and copper boxes for storing dross, gee-rags, and lamp wick, as well as a trash receptacle shaped like a miniature spittoon. Brass tools for scraping dross from the inside of pipe bowls leaned against their own matching stand, next to a rest for the all-important opium needle.

All these rare and wonderful things were upstaged by what in my opinion is the holy grail of antique opium paraphernalia collecting: a shade for the opium lamp—in this case a silver cicada whose eyes were set with rubies. To smokers of yore, the burbling sound of an opium pipe was said to echo certain sounds found in nature—particularly the mating calls of cicadas, frogs, and a species of freshwater crab. Thus these three creatures became opium smokers’ mascots, and to honor them as such, artisans crafted their images onto paraphernalia. Our cicada lampshade hung from the lip of the lamp’s glass chimney, blocking the glare just so—a whimsical remedy for the opium smoker’s heightened visual sensitivity.

“These old-time smokers were like children with their toys,” Willi once remarked to me during a session. This, I theorize, was what kept the makers of fine paraphernalia in business. Just like kids, the smokers would have tried to outdo one another, always competing to be the one with the coolest playthings.

The more we used the antique paraphernalia, the more evident it was to us that many of the finest smoking accoutrements were created with the heightened senses of opium smokers in mind. The astounding attention to detail—the filigree-like openwork, the ornately ornamented surfaces etched with lines as light and tight as a feather’s—all of it was meant to catch and dazzle the opium-thrilled eye. To prop myself up on one elbow and behold our gleaming layout in the darkened room made me feel like a storybook giant who had stumbled upon a miniature city of gold—a shining El Dorado in some lost valley, banishing gloom with its magical radiance.

Likewise, the textured surfaces on the handles of the tools, lids, and other bits meant to be touched were there to titillate those millions of hypersensitive nerve endings on a smoker’s fingertips. The full genius of the artisans’ efforts to create pleasing textures was most abundantly experienced by the lips. No kiss has ever been sweeter, more supple, or more enchanting, than that of an ivory mouthpiece upon the lips of an opium smoker.

In the most basic sense, the huge layout—the pipe and lamp and sundry tools spread out upon their respective trays—was a system for keeping the involved and messy process of opium smoking as organized and tidy as possible. But to Willi and me, it seemed much more significant. Many pieces of our paraphernalia had been handled by long-departed souls who were adept at spinning the sap of poppies into dreams. We came to believe that the accumulated knowledge of this escapism was trapped within the paraphernalia itself, and that by using it, Willi and I were somehow learning important truths that had been long lost. Our sessions, progressively more blissful with each meeting, seemed to bear this theory out.

Once the layout seemed perfect, Willi and I turned our attention to the space that hosted our sessions. After Willi had arranged for the basement storage room to be emptied, we gradually introduced decorative objects and period furniture from old China. Neither of us had the means to complete the embellishment of our smoking room all at once, but we felt that our inability to instantly transform the space made us more selective and gave us time to appreciate each new addition.

Our decorative theme evolved in a way that made the room seem as though it, too, had gone through several permutations over time. Originally we conceived of the space as a classical Chinese study—a place of solitude that might have been used by some bespectacled student preparing for the imperial examinations. Later, as the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth and the Qing dynasty fell to Sun Yat-sen’s republic, our room, as did all of China, came under the influence of Western ideas. This could be seen in the English-made pendulum clock we positioned prominently on the wall, as well as the framed American sheet music covers that hung between scrolls of calligraphic poetry on rice paper. But our march of time had stopped in Jazz Age Shanghai—in the 1930s—when the Japanese invasion of Manchuria had given China a fatalistic, devil-may-care attitude that the invaders encouraged by making opium more plentiful than ever before. At some point during the transformation, Willi christened the room: “the Chamber of Fragrant Mists.”

It was in this safe haven that Willi and I smoked opium on a regular basis from 2002 to 2006. Upon my arrival—usually at mid-morning in a three-wheeled motorcycle taxi—Willi would be waiting on the verandah and, after a hearty greeting, would direct me to the shower where I could scrub off the grime of a night’s worth of tropical train travel. Then I exchanged my modern clothes for loose-fitting Chinese pantaloons, black cloth slippers, a white silk singlet, and a smoking jacket of brocaded indigo silk. This latter garment was also an online purchase—a relic with tags stitched into the lining indicating that it had been tailor-made by a shop on Yates Road in old Shanghai’s International Settlement. Perhaps it had been worn by Silas Aaron Hardoon himself—called the “Baghdad Jew”—who amassed a fortune trading opium in what was then known as the “Wickedest City in the World.”

Once Willi and I were properly outfitted in period clothing, it was time to conduct the many pre-smoking rituals that we performed before the start of each session, descending into the dark and shuttered Chamber after weeks of absence. The old pendulum clock was set and wound only when the Chamber was in use—kick-starting time in our Chinese Brigadoon. I usually did the honor myself, fingering the pendulum into action and twirling the minute hand round and round until the clock caught up with time, the lost hours bonging away frantically.

Then, once the clock was in motion, I gave my attention to the calendar. The number prominently displayed on the hanging pad of pages indicated the last date we had filled the Chamber with the sweetish scent of opium. One at a time I tore away pages until the present date appeared, making sure the sound of each one being ripped from the pad was clear and distinct. When the pages to be torn away were many, we lamented the time lost to mundane activities—how could we have squandered so many days without a visit to our beloved Chamber? If the pages were few we congratulated ourselves on having so soon found time to indulge.

After the clock and calendar had been adjusted, I then made offerings of candles and incense to the Den God, an image of a nameless Chinese deity that I had rescued from a dusty stall at a flea market in Bangkok. Willi had converted an empty corner of the room into an elaborately gated shrine for the deity, framing it with decorative wooden panels that were salvaged from the interior of a demolished Chinese mansion. Upon the altar were smoldering sticks of incense and thick red candles whose tall flames softly illuminated the benevolent face of the Den God. Ribbons of smoke rose from the glowing tips of the joss sticks, stretching upward through the breezeless air in slender columns that billowed against the red lacquered ceiling. After countless sessions, the room’s surfaces became coated with the oily smoke of incense and opium, bestowing upon everything the glossy sheen of antiquity.

Dominating one wall of the room was a huge old Chinese shophouse sign that I had bought at an antiques shop in Penang while updating a chapter of a guidebook about Malaysia. Made long ago from a single block of black lacquered wood, the sign consisted of two Chinese characters deeply carved and detailed with gold leaf. During our sessions, the faintest candlelight would reflect in the sign’s gilt recesses, causing the characters to shimmer softly above the room. When I first saw the sign in the antiques shop, I was only making conversation when I asked the proprietor to translate it for me. The sign read “Doctor with Peerless Hands.” I immediately bought it for the Chamber and in so doing, Willi gained a new nickname: “The Doctor.”

On a long, narrow Chinese table positioned against another wall, Willi had arranged two wooden racks to display our pipes. Hanging above this was a wood and glass curio cabinet with our precious hoard of pipe bowls stored under lock and key.

Over the years we covered nearly every inch of the Chamber’s brick walls with vintage Chinese advertising, old photos, and obscure, opium-related ephemera. My contribution was our collection of American sheet music covers—reminders of a time when opium smoking in America was so commonplace that it was the subject of popular songs. The oldest was Will Rossiter’s “I Don’t Care If I Never Wake Up” from 1899. There was also “Roll a Little Pill For Me” by Norma Gray from 1911, and Byron Gay’s “Fast Asleep in Poppyland” from 1919 (chorus: “Lights burn low / dreams come and go / dreams of happy hours / spent among the flowers”).

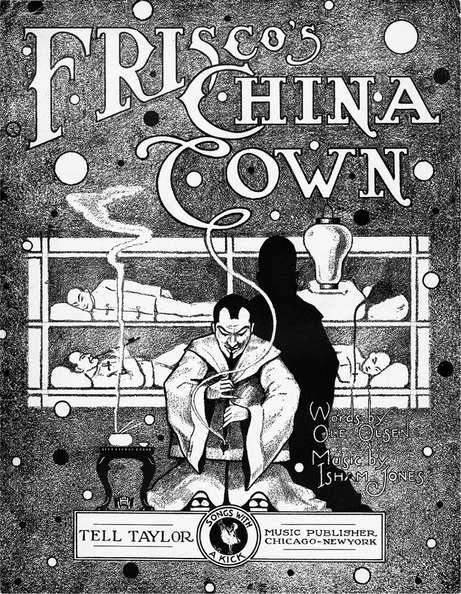

Our favorite for cover art was Ole Olsen and Isham Jones’s “Frisco’s Chinatown” from 1917, which featured a depiction of an opium den with four pigtailed Chinese slumbering snugly in the tiered bunks that were a common space-saving arrangement in American “hop joints.”

Sheet music cover from 1917 with a depiction of a typical “hop joint” in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Between the 1890s and the 1930s, opium smoking was so well known in America that it was mentioned in popular songs, many of which also reflected the association of the habit with Chinese immigrants, who introduced it from China in the 1850s. (From the author’s collection)

The old song sheets notwithstanding, Willi and I preferred silence over music while smoking. Any loud, sustained noise—any sound other than the steady tick-tock of the pendulum clock—would mask the gentle burbling sound of the pipe. If a smoker cannot hear his pipe, the sound of which resembles the dregs of a milkshake being lightly sucked through a straw, he can’t tell if the opium is properly vaporizing, especially since the vapors of good chandu do not burn the throat or lungs like tobacco smoke.

The all-important opium bed, the room’s centerpiece, was a heavy, baroquely carved rectangular hardwood platform. Unlike a traditional bed, the two long sides of an opium bed are its head and foot. Ours was positioned with one long side—the bed’s head—against a wall. The head and sides of the bed were enclosed with wooden panels about two feet high, meaning that it could only be mounted from the foot. This was designed to afford privacy to the bed’s occupants, keeping out any unwanted distractions and helping to cut down on drafts that might make the opium lamp flicker. Our opium bed was additionally sheltered from the rest of the room by a low-hanging canopy of silken brocade woven with elegant floral motifs that were just faintly visible through the smoky gloom. The result was a womblike space within a space, enveloped by darkness and quiet, a willful cocooning against the world.

I always looked forward to my weekends away from Bangkok with its gridlocked thoroughfares and ubiquitous construction sites towering above gouged and pummeled earth. In my mind it wasn’t the opium that I missed—it wasn’t the high that I craved. What I longed for was sanctuary from the modern world. Life outside the Chamber seemed increasingly cruel. Out there were the twenty-first century, war, and terror. A relentless feed of information made far-off events difficult to ignore, but even if I could turn my back on the larger world, the situation around me was just as disturbing.

The Southeast Asia that Willi and I had both gravitated to in our respective youths had grown modern and materialistic. We both watched in dismay as many of the quaint traditions and customs that had attracted us to the region in the first place vanished before our eyes. Westernization is the bugbear most often cited as causing the demise of old Southeast Asia, but, in fact, the majority of changes we saw were brought about by the relentless rise of new China.

The behemoth’s influence could be seen everywhere, but most noticeably in the region’s largest cities. During the 1990s, Southeast Asia began giving up its traditional architecture of teak and brick and stucco for modern Chinese-inspired concrete boxes clad in glazed tiles and tinted glass. Local craftsmen were squeezed out by a flood of impossibly cheap Chinese goods. Most affected were the ethnic Chinese themselves, descendants of a nineteenth-century exodus from the country’s turbulent past. Generations of living in Southeast Asia had bestowed upon the great-grandchildren of that first wave the easy habits common to people who live in tropical lands of plenty. They were no match for these new Chinese—famished after decades of austere Maoism and accustomed to using sharp elbows to push to the head of the line. When in 1992 Deng Xiaoping declared “To get rich is glorious,” his mantra soon carried his countrymen on a renewed push for China’s traditional southward expansion. As the century turned, the pace of modernization quickened as China became richer, and billions were invested in Southeast Asia. The swiftness of change was astonishing.

If Willi and I had allowed outsiders into the Chamber to gaze upon our meticulously re-created surroundings and to witness our cryptic rituals, most would have concluded that we were a couple of eccentric Sinophiles. But such assumptions would have missed the point. Willi and I were fans of the old, inscrutable China, its mysteries and idiosyncrasies an essential part of its charm. Opium was our time travel back to that simpler era before China—and the whole of East Asia—became known for karaoke-caterwauling and crassness.

While under the narcotic’s optimistic influence, Willi and I strove to re-create that romantic period in Chinese history when a poet might spend the day flying a kite while drinking rice wine spiced with chrysanthemum petals. New China, as well as the rest of the modern world, was a horror to us, and we went to great lengths to ensure that it ceased to exist the moment we entered the Chamber of Fragrant Mists. There were no telephones or other ways of communicating with the outside world allowed in the Chamber, and while there ensconced we never discussed current events.

Instead, we might try to identify the calls of wild birds that inhabited the thickets of bamboo on the far side of the lotus pond. We might discuss the merits of a Tibetan rug—shaped and patterned like a tiger skin—that Willi had bought from the estate of a long-dead British civil servant who had once maintained a bungalow near Mandalay. Willi and I might take turns reading aloud passages from some of our favorite books (David Kidd’s Peking Story and John Blofeld’s City of Lingering Splendour were always at hand), and at least once during each session Willi’s wife would come down to the Chamber to say hello and recline for a pipe or two.

Willi and I spent hours in each other’s company, but flagging conversation is never a problem with opium smokers. As the hours passed and the number of pipes smoked increased, we found ourselves in the Land of the Gentle Nod, a state somewhere between slumber and wakefulness, like that last second of consciousness before one drifts off to sleep. Here the clock would slow to such a crawl that lifetimes seemed to pass during the pauses in our conversation. Opium is its own timekeeper, as every smoker soon learns. At that time, when I was but a novice to smoking and enjoyed a nightlong session perhaps once a month, a single night on opium left me feeling that I knew the true meaning behind the title of Gabriel García Márquez’s first novel. Years later, after I had begun rolling my own pipes and smoking alone, hours could pass in three nods of my poppy-fogged head. I would light the lamp just before midnight and then, seemingly within minutes, an unwelcome dawn was worrying the curtains.

Over time, a single night in the Chamber seemed inadequate and my one-night trips to visit Willi became long weekends. These two- and three-day sessions, when we could manage them, were sublime. Willi had a talent for Old World hospitality and he often spent a whole week preparing for one of my visits, ensuring that arrangements were perfect in every detail.

Food may not seem to be compatible with opium smoking, but in fact the high-quality blend, when used in moderation, produces in the smoker both the desire and the ability to enjoy food. Our fabulously rare chandu heightened all senses of perception, including taste. Once we had discovered this, Willi and I added an aspect of culinary adventure to the opium equation.

Like everything else in the cosmos, Chinese foods can be divided into two groups, depending on whether they possess cooling yin or heating yang properties. Since opium is female—or yin—smokers favored masculine yang foods to keep things in balance. During its nineteenth-century heyday, opium smoking gave rise to a complementary cuisine. But, like just about everything else pertaining to opium culture, the knowledge, if not altogether lost, had been hidden away and forgotten. It wouldn’t be a matter of searching Amazon for a cookbook.

Instead, I was in charge of poring through my books in hopes of running across a reference to some opium smoker’s favorite recipe that we might resurrect. Willi might then drive his pickup truck to northern Thailand just to buy smoked boar’s meat sausages from a butcher at some Kuomintang village that he had passed through and noted years before. Back in Vientiane, Willi would seek out elderly members of the Chinese community and then, with uncommon ingredients in hand, talk them into preparing morsels that hadn’t been attempted since mid-century revolutions and migrations had made them unthinkable luxuries.

The result of all these preparations were halcyon days spent gently padding back and forth between the incense-scented coolness of the Chamber and the warmth of the sun-soothed pavilion over the lotus pond. In the shade provided by the pavilion’s roof, its thick wooden shingles covered with feathery moss, sat a low teakwood table. By mid-morning Willi’s servant was busy arranging the tabletop with rows of porcelain bowls, each containing some delicacy that Willi had spent the previous days procuring. There was pickled ginger dyed a lurid pink that seemed to match its spicy tang; flaky Chinese pastries whose waxy red and yellow markings codified sweet and savory fillings; spongy buns from which escaped a sigh of steam when torn in half—and all of it washed down with countless thimble-sized cups of slightly bitter, palate-cleansing tea. Willi directed that our banquets be served in leisurely, unhurried courses that punctuated our smoking sessions and lasted well into the night. Once the old servant had cleared away the crumbs and dregs, applause for Willi’s efforts took the form of creaking wicker as our satiated bodies sank deep into rattan chairs.

When the echoing calls of night birds became more urgent, and the fireflies’ luminous signals began to wane, we took them as signs to leave the rapidly cooling outside air for the warmth indoors. We might continue to smoke until midnight, and Willi would then roll us a nightcap—a last pipe or two—before blowing out the lamp and retiring to his room upstairs, leaving me to lounge away the sweetened night alone in the Chamber.

Opium puts one on the verge of sleep, but if smoked to excess the threshold of sleep cannot be passed. I always smoked too much and could never fall asleep. Yet far from feeling the frustration of insomnia, I savored these hours of drifting in limbo. I would pass the night lying on my back with my fingers laced upon my chest, my eyes closed so their inner membranes could serve as screens upon which deeply buried memories were projected. The clarity of these visions delighted me, and the rush of love that I felt upon seeing a family member or a childhood friend sometimes brought me to tears.

These might be termed “opium dreams” by some, but they were really no more than memories that opium had made more vivid—fragile images that vanished as readily as dust blown from the cover of an old book. As long as I focused on the memories they were there, but opium in excess works against concentration, and the encounters were fleeting. Between these images were playbacks of conversations that Willi and I had had earlier that day. One exchange in particular came back to me. It was based on a nagging question that of late had made even my most rapturous moments bittersweet: Must this end?

“Willi, you know, every time I think to myself that this simply cannot get any better, I also can’t help but wonder how long we can keep it up.”

Willi had raised himself up from the bamboo mat in order to best use a wooden back scratcher to dig at the small of his back. He looked at me with bliss-heavy eyes and then turned to address the Den God in its little cove of drippy candles. “I don’t see any reason we can’t keep this up forever as long as we’re disciplined about it,” he said. “Obviously the dangers of becoming addicted have been exaggerated. Look how long we’ve been doing this.” Willi paused and then asked, “After you’ve gone back to Bangkok do you find your cravings for opium unbearable?”

“Mondays I usually sleep most of the day. Tuesdays I often have a yen,” I said, purposely using some vintage slang to amuse Willi.

Willi chuckled and rose to the occasion—the Chamber library included an old book with an extensive list of dated American underworld slang. Slipping examples into conversations was one of our favorite Chamber pastimes. “You’re just a joy-popper with an ice cream habit,” Willi quipped. He then said with some seriousness: “As long as we keep to once a month or so, we can’t get hooked.”

“Well, as long as kicking the gong is a train ride away, I guess I don’t have to worry. I don’t know how you do it, though. If the Chamber were as close to me as it is to you, I’d be on the mat every day.”

Willi shrugged. “I have other poisons. I drink a bottle of Prosecco nearly every day. Of course, alcohol is a crude substitute for chandu, but I can’t afford to become hooked. This stuff costs more per ounce than gold. If somehow things got out of hand, it would bankrupt me.”

“So how do people maintain habits?”

“Do you mean those dross-smoking skeletons puffing away down at Kay’s?” Willi winced. “Where’s the joy in that?”

Then Willi broke into a smile as a thought came into his head. “There is someone who maintains an old-fashioned habit. I’ve never told you about her, but it’s her patronage that makes it possible for me to keep the Chamber stocked with chandu. She’s a real old hand—an American left over from the war in Indochina. And as it happens, she’s due for her annual visit next month. Would you like to meet her?”