Thus it was the master, Beelzebub opium, led his imp a devil dance constantly.

—William Rosser Cobbe,

Doctor Judas: A Portrayal of the Opium Habit (1895)

In April 2008, after five long months of avoiding Roxanna, I finally felt I was ready to pay a visit to her home. The occasion was a visitor from the States, a collector I met through eBay who had during my time of dependence bought some of my desperate offerings and kept me afloat. Justin was visiting Thailand for the first time, and after talking with him, I was impressed with what he knew about opium smoking—especially from a medical standpoint. Justin was able to explain to me in laymen’s terms why I was suffering so:

“Think of the receptors in your brain as hungry little mouths. Normally they feed on endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers and mood enhancers. But if you start regularly feeding those little mouths with the much more delicious opium, they’ll get spoiled. Take away their daily feast of opium and expect them to be happy with endorphins instead, and your body and brain will revolt until you give the receptors what they want. And they won’t give up easily. The receptors must be fed opium or some other opiate, or you’re really going to suffer. After many months of life without opium, the little mouths will get used to eating endorphins again. But they still remember the taste of opium, and if you smoke it again just once, their angry demands for more will be impossible to ignore.”

After some hours spent discussing this and many other details pertaining to opium, I got the idea to take Justin with me to Roxanna’s house. I knew he would be very interested to see her in action, and his being there would take the pressure off me to smoke—since Roxanna would have another guest to prepare pipes for.

I called Roxanna—the first time in recent memory that I was doing the calling—and proposed the idea. She knew Justin’s name because we used to talk about what I was going to sell and to whom. Justin was one of two collectors in the United States to whom I regularly sold, and I was happy that I had established a friendly relationship with him. I hoped that someday I might be able to buy back some of my pieces, but if that were to happen, it was going to be far in the future. Since I had neglected to keep in touch with editors, I was no longer being offered many freelance writing jobs, and I was still struggling to get back on my feet.

The afternoon of the following day, Justin and I took a taxi to Roxanna’s neighborhood, trading the car for a pedicab once we reached the market where the lane narrowed. A pedicab was the most scenic way to arrive, and this lane was one of very few in Bangkok where they were still in use. During the ride in, Justin asked me questions but I was unable to concentrate and kept asking him to repeat them. In my mind I was rehearsing the scene when Roxanna would offer me a pipe—it was inevitable—and I would calmly decline.

“When was the last time you were over here?”

“I’m sorry, what was that?”

My mobile phone rang. It was Roxanna, asking if I could buy her a pack of cigarettes at the corner store. I said that we had already passed it, and she said never mind, she would borrow a cigarette from her Thai brother-in-law.

“We’ll be there in three minutes,” I said.

“Okay, the door is unlocked, just let yourself in. I’m upstairs already.”

Familiar routes and familiar routines that in the past had always led to bliss. We disembarked from the pedicab and walked the concrete causeway, the hot afternoon sun making the frond-like leaves of the banana trees droop limply. At Roxanna’s doorstep we ran into her brother-in-law and his wife, an amiable couple whom I had been on friendly terms with. They looked both surprised and happy to see me, and paid me a typically Thai compliment by remarking that I’d gained weight since I was last there for a visit.

I introduced Justin, and then the two of us made our way up the narrow wooden stairway. Roxanna was taking her cigarette break, and I immediately noticed the layout tray was littered with dross, indicating that she had been smoking opium for some time before we arrived. I had only seen her do this once before—when she was hosting both myself and her old Vietcong friend who was visiting from Vietnam. That day, she had smoked her fill first so she could concentrate on rolling for her guests. Remembering this, I took it to mean that today she was expecting me to smoke, too.

Roxanna and Justin exchanged greetings, and I invited him to recline alongside the layout tray. I then took a seat in a dusty wooden armchair situated in a corner of the room. The chair had been there almost as long as I’d been coming to smoke with Roxanna, but this was the first time I had ever sat on it. My place had always been on the floor.

Roxanna stubbed out her cigarette and began counting drops of chandu into the miniature wok while she and Justin chatted about his flight over. Just as in the pedicab, I was having a hard time focusing on the conversation and felt unable to join in. The musky smell of opium soon drove the sharp odor of cigarette smoke from the room, and I sat bolt upright in the chair, crossing my legs and arms in a subconscious effort to stiffen my resolve.

Justin was soon drawing on his first pipe—quite expertly I noticed—and the soft, sputtering sound of opium being vaporized took over my senses. A lotus pond full of croaking frogs; a summertime flame tree abuzz with cicadas; a maddening ringing in the ears; the forlorn sound of crying babies. I could not hear a thing they were saying above the din. I sat and stared, deafened and dumbstruck, and suddenly I remembered seeing my Time buddy Karl Taro Greenfeld staring at me goggle-eyed from a dark corner of that opium den in Vang Vieng seven years before. I remembered thinking, What’s his problem?

Now I knew.

After Justin had smoked three pills, Roxanna held up the pipe and gestured with her needle, pointing it at the bowl. “Do you want one, too?”

“No, thank you,” I heard myself say.

“Okay,” she replied. Her tone said: Suit yourself.

The room was closed up as usual to keep out drafts that might make the opium lamp flicker, and the heat was becoming unbearable. Although I didn’t think there was much chance of inadvertently breathing in any opium fumes—because I was sitting off by myself in a corner—I still felt as though I needed to get out of there. I looked at my mobile phone and saw that barely fifteen minutes had passed since Roxanna had called me. It would be awkward if I tried to leave now.

I closed my eyes and ran my detox mantra through my head, concentrating on each syllable in an effort to push out all other thoughts. The effect was not what I’d expected. Somehow the exercise was making me drowsy, and soon I felt that I was nodding off, entering that relaxing state just between sleep and wakefulness. My head dipped abruptly, causing me to snap back awake. Roxanna noticed this and asked if I wanted to take a nap downstairs in her bedroom. I jumped at the idea.

Lying on Roxanna’s bed with the air-conditioning on, I found myself wide-awake again. I looked around the room and took in her life. Above her bed was the framed black-and-white photo of a very young and beautiful Roxanna in Vietnam-era jungle fatigues. Over the door was an oversized ornamental fan adorned with an Asian village scene painted in garish swipes. On the plywood wall near her vanity were snapshots of a decades-past trip to America: Roxanna and her Thai husband were riding bicycles on some tree-lined suburban street. Jamie, just an infant then, was strapped into a kiddie seat. There were photos of Roxanna’s wedding—both bride and groom wearing traditional Thai dress and kneeling in what looked like a Buddhist temple. There was a small shelf with academic books about Asian ceramics, and I noted that my own book was among them. A clothes rack in lieu of a closet was hung with her silk and batik wardrobe. Besides the rack, the bed, and a vanity and stool, there was no other furniture.

The luster of romance that I had once seen in Roxanna’s life was tarnished considerably now that the opium had left my system. Roxanna was sixty-two, her health was fragile, and she was working to support her son and Thai in-laws and their extended family. On top of that she had this expensive drug habit that was steadily draining her finances as well as her vitality. I decided then and there that I would talk Roxanna into doing detox at Wat Tham Krabok. I was sure I could do it—I just needed an opportunity to talk to her privately.

After another hour, I heard Justin and Roxanna making their way down the stairs, and I came out of Roxanna’s bedroom to meet them. I thanked Roxanna for her hospitality and told her that I would be calling her very soon. Justin wanted to walk out to the main road in order to have an unhurried look at the neighborhood, and as we talked on the walk back, I felt good for not having broken down and smoked. I had the strength to pass such a test, and I was sure a second time would not be so difficult—especially now that I had a mission.

As soon as I got home I called Roxanna and asked if I could come over that Sunday. She sounded delighted with the idea. “Are you going to join me this time?” she asked.

I didn’t want to say no, or even worse, to sound undecided. I was afraid this would perhaps cause her to feel guilt, which might, in turn, make her nix the idea of my visiting. I had to sound sure of myself.

“Yes, I’m ready,” I confirmed.

Over the next few days I rehearsed what I would say to Roxanna. I wouldn’t rush into the proposal. If she had a few pipes in her system I knew it would help her to think clearly and be more receptive to my idea. I would keep from smoking by telling her that I had just eaten and needed to let my stomach settle before having a pipe. This would not seem strange; neither of us ever began smoking on a full stomach.

Sunday morning I arrived at Roxanna’s with an elaborate plan that began with a lie about having been forced to eat a gift of mangoes and sticky rice. “One of the old lady vendors who I always buy from handed me a box of mangoes and sticky rice as I was on my way out to get a taxi. Somebody ordered it but hadn’t picked it up and she was afraid it would go bad in the heat. I thought I would just eat the mangoes but somehow I couldn’t help myself and before I knew it, I’d eaten the sticky rice, too.”

“Oh, next time bring some over, I’ll share it with you,” Roxanna said.

I promised I would, thinking to myself that the next time I visited Roxanna, she would be off opium. We could share the mangoes and sticky rice as a little celebration. Roxanna and I went upstairs, and I immediately shut all the windows and began helping set up the layout. It wasn’t even nine o’clock, but the morning air was heavy with heat and humidity. I looked at the dusty chair in the corner and was glad that I’d be reclining on the relatively cool wooden floorboards. I told Roxanna that I probably needed an hour or so for my stomach to settle and to go ahead without me. “I’ll catch up soon as I feel a little less bloated,” I lied.

I stretched out on the floor, leaving a couple feet of distance between myself and the layout tray instead of lying right up against it as a smoker does. I let my head rest on a porcelain pillow, but I chose to lie on my back instead of facing the tray. Soon the old ritual began. While I stared up at the asbestos roof tiles, I could hear but not see chandu sizzling in the copper wok. Once again I closed my eyes and fell back on my detox mantra. Roxanna said nothing. She often used to take catnaps between pipes, and she believed that I had a belly full of glutinous rice—the tranquilizing effects of which must be experienced to be believed. Just as before, concentrating on the mantra put me to sleep. When I awoke half an hour later, my head was absolutely clear.

“Well, you must’ve needed that,” Roxanna said as she put down the pipe and lit a cigarette. “I’ll roll one for you as soon as I finish this.”

Now is the time, I thought to myself. I went straight to it. “Rox, have you ever tried to quit smoking? Opium, I mean.”

She blew the cigarette smoke from her lungs, as always taking care to exhale away from me. “Why, yes, of course. Many times.”

“Would you like to be finished with it for good? In just a few days and with almost no pain?”

“Go on,” she said with genuine interest.

“There’s this wat north of here. In Saraburi. They have this detox program …”

“You don’t mean Tham Krabok, do you?”

“So you know of it.”

Roxanna smiled. “That’s where I met my husband.”

“What?”

“Oh, it’s a long story. Let me fix you a pipe and I’ll tell you.” Roxanna lifted the cap from her dropper bottle and started to count drops into the tiny wok.

“How did that happen? Were you doing a story about the wat and met your husband because he was doing detox there?” I was sitting up cross-legged now. I knew the business end of the pipe would soon be pointing at me, and being out of position to receive it would give me an excuse to delay smoking.

“No, this was long after I stopped doing journalism. In the late seventies I was living in Hong Kong working for Arts of Asia magazine. I got arrested for smoking opium and deported. That’s when I came to Thailand and went to Tham Krabok to stop smoking. My husband was a monk there.” Roxanna had finished rolling the pill and it was now stuck to the bowl.

“So the detox at the wat didn’t work for you?”

She smiled again. “Well … here I am.”

“So that means … I mean, I’ve heard you can only do the detox once. They won’t let you go back and do it a second time.”

“Yes, that’s right. I already had my chance,” Roxanna said.

It is said that even after his famous cure, Jean Cocteau went back and dabbled. Of all his quotes from Opium: Diary of a Cure, there is one that, for me anyway, was clear evidence of this: “The patience of a poppy. He who has smoked will smoke. Opium knows how to wait.”

What’s the harm? I suddenly thought to myself. I straightened out my legs and leaned back, the right side of my face coming to rest on the porcelain pillow. It was cool against my cheek and ear. Roxanna pointed the pipe toward me and I guided the mouthpiece to my lips. The heated bowl crackled almost fiercely as I hungrily sucked the vapors into my lungs. The pill vaporized in an instant and I held my breath for as long as I could before exhaling a near-invisible stream at the roof. It was as easy as that. Looking back, I don’t know why I did it. I just did.

Without asking, Roxanna began to measure out another dose. I didn’t feel any effect yet from that pipe, but it had only been a minute or so since the vapors left my lungs. I closed my eyes and waited.

“Really, it was probably the worst decision I ever made in my life,” Roxanna continued.

“You mean doing the detox?”

“No, no. I mean breaking my vow never to smoke opium again. They warned me something terrible would happen if I broke that vow. I tried it just once with an old friend and it wasn’t long after that I had my motorcycle accident and lost my leg.”

I kept silent. Surely it was just superstition. Or the power of suggestion. Or a horrible coincidence. That vow was just to scare those meth-crazed kids into stopping. Those Buddha statues that I took the vow before were just pieces of cast bronze.

“Then in the hospital the doctors filled me up with morphine. Nobody expected me to live. My Thai family had to beg the doctors to treat me because they were all convinced it was a waste of time. I wasn’t even in a room, they just had me on a gurney out in the hallway because they were expecting to release my body to my family in a short time.” Roxanna finished preparing the second pipe and handed it to me. I took it and smoked the pill slowly this time, again keeping the vapors in and only letting go when Roxanna gave me a mild scolding. “That’s really bad for your lungs,” she said.

“I’m sorry, can you roll me another?” I asked.

During the next several pipes Roxanna told me in detail about her accident. It happened in Bangkok at the intersection near the famous Erawan Shrine. She told me of how the driver of a ten-wheeled truck had plowed into her motorcycle and then fled the scene. She described how being crushed under the wheels left her so disfigured that her Thai husband soon abandoned her. Roxanna’s first prosthetic leg was a constant source of pain, but even after she had been fitted with a more comfortable one, there were still social obstacles to overcome. She told about a Thai male colleague at the ceramics museum who sought to undermine her position by using her disability against her—at one point even going so far as to order the staff to move the museum library to the third floor so Roxanna would have to climb the stairs every time she needed to look something up.

“You don’t really believe that, do you?” I interrupted. “I mean, about breaking the vow causing your accident?”

“Yes, I do!” Roxanna said with widened eyes. “And I’ve heard stories about other people who broke that vow and had bad things happen to them, too.”

Roxanna never struck me as somebody who bought into the paranormal. We had spent many hours together discussing everything under the sun, and I had never once gotten the idea that she let emotion stand in the way of reason. Life had made Roxanna pragmatic, but perhaps this was an exception to her pragmatism. Surely the horror of her accident would have made a deep impression on her. I might feel the same way about breaking that sacred vow had I gone through what Roxanna had. How else to explain being randomly visited upon by such violence and subsequent hardship?

I listened to Roxanna’s story and tried to think things out, but there was something more worrying to me at that moment—more worrying even than a karmic curse. Roxanna had already prepared ten pipes for me, yet I felt absolutely nothing. There was no opium electricity, no opium tingle, not even an opium itch.

“It’s the damnedest thing, Rox. I just don’t feel anything.”

I went home that afternoon angry and frustrated. Angry at myself for having broken my vow not to smoke opium; frustrated because I had gotten nothing out of it. I felt completely sober. There was only one noticeable effect but I wouldn’t realize it until the following day: The ten pipes had ossified my intestines with constipation.

Over the next few days I thought a lot about what had occurred. I remembered having a similar experience on at least one occasion in the past—a night during which I seemed unable to feel opium’s distinctive intoxication. It happened during my period of heavy smoking. Despite everything working properly and more than my usual number of pills, I simply could not get high. I remembered chalking it up to my own mood that night, thinking that I’d created some sort of psychological block. The following night I had smoked again—that very same batch of chandu with the very same pipe and bowl—and I got so cooked that I felt my head melting into the porcelain pillow.

I called Roxanna on Friday and asked if I could visit that weekend. She replied that any day was good because her son was staying with friends in Chiang Mai. “Saturday’s fine. Sunday’s okay, too. Whichever day you decide not to come I’m going to spend at my office to escape the heat.”

With beating the heat in mind (as well as being anxious to try smoking again as soon as possible), I chose Saturday morning, asking if it was okay if I arrived early. We agreed on seven, and that night I got little sleep due to the excitement of an imminent session. I wasn’t worried about a relapse. On the contrary, I decided this was just the corrective I needed to keep life interesting. Perhaps once a month at most: I would smoke opium no more frequently than that. But first, I needed to get the full feeling again. Then I would lay off smoking for a month or so.

Roxanna was downstairs drinking a fruit smoothie when I arrived. This was her usual dinner, which her brother-in-law prepared and brought over from his nearby house every evening. Roxanna explained that she hadn’t been hungry the night before and so had saved it in the fridge. “Do you want some?” she asked. “There’s more than enough.”

I declined because I had bought two bottles of Gatorade at the 7-Eleven before hailing a taxi. I got a glass from the dish rack and some ice from the little Igloo cooler that served as an icebox while Roxanna asked how I’d slept the night after our session. Normally we never discussed opium downstairs, but Jamie wasn’t home and although Roxanna’s neighbors could clearly be seen and heard through the slatted walls, there wasn’t another English-speaker within miles.

“It was really weird. I just didn’t feel anything,” I said.

“Well, you haven’t smoked in a long time. Maybe you need to build up a little in your system.”

“Does that make sense?” I asked.

Roxanna chuckled. “No, it doesn’t. Not in my experience, anyway. If you haven’t been smoking you should need less, not more.”

Roxanna started up the stairs and I waited until she got to the top. She climbed the stairs slowly but steadily without her cane, and I didn’t want to crowd her from behind. Once I caught up with her, I closed the door behind us and started arranging the layout tray. It was just like old times. As Roxanna was lowering herself to the floor I said, “Let’s wait to close the windows until you’ve trimmed the wick and you’re happy with the flame. I’m afraid as soon as these windows are shut it’ll heat up like an oven in here.”

“Yes, it will,” Roxanna replied simply. She began adding coconut oil to the lamp and it overfilled, spilling some onto the lamp tray. “Oh, darn,” she said to nobody in particular.

Once everything was set and Roxanna began rolling pipes for me and herself in succession, she told me about a trip to America that she would soon be embarking on. It was one of her academic junkets, something that she did a couple times a year. These trips usually involved Roxanna speaking about Southeast Asian ceramics at some university. The way she excitedly talked about these events made it obvious that Roxanna really enjoyed the opportunity to share her passion and see colleagues from around the world. During the time that I had known her, Roxanna had traveled a number of times: to the Philippines, to Singapore, and, if I remember correctly, to Australia. This time it would be Seattle, to give a lecture at the University of Washington.

“I’ve been working on my talk for weeks now. Do you want to hear it?”

“Sure.” I was a bit preoccupied, worrying because I had already smoked four pipes and still didn’t feel anything. Perhaps if I concentrated on listening to Roxanna’s lecture, the buzz might creep up and pleasantly surprise me.

“Could you go downstairs and get it? You’ll see it on my bed in a blue plastic folder. Oh, and could you bring me up a cigarette?”

I popped downstairs and into her bedroom, grabbing a single cigarette from the pack on her vanity. I caught a glimpse of her old snapshots tacked to the plywood wall, curling in the tropical heat. I felt a pang of something. Was it guilt? I really could have pressed Roxanna to go back to Wat Tham Krabok. It was doubtful the monastery still had records of people who took the cure so many years before. Her current passport number would be different from the one she used back then. The wat would probably have taken her back no questions asked.

I walked out the bedroom door but as I mounted the stairs, my thoughts had already turned to something else: smoking. When I entered the upstairs room I saw that Roxanna was now standing. “I can’t do this lying down,” she said. “I need to pretend I’m behind a podium to get some real practice.”

So I handed her the folder and took her place on the floor beside the layout tray. “Do you mind if I roll for myself?” I asked. “I need some practice, too.”

“Go right ahead,” she said.

While Roxanna was reading her lecture, I began preparing a pipe as though none of the past year had ever happened. I pushed the guilt I’d felt earlier out of my mind. Things happen for a reason, I told myself.

My own interest in ceramics was very narrow: If it was a component of an opium pipe or some other piece of opium paraphernalia and it happened to be ceramic, I was interested—otherwise, I paid little attention to it. So while I listened to Roxanna speaking, the details were lost on me. Yet, I could appreciate her passion for the subject. There was pride in Roxanna’s voice as she sought to share her knowledge of a subject that, no matter how esoteric, was hers.

“The Ming Gap.” My fondness for idiosyncratic juxtapositions of words made the term stick in my head, but I only had the most basic understanding of what it referred to. It didn’t matter. What the Ming Gap meant to me was how much Roxanna and I had in common. We had both exiled ourselves on these exotic shores and then set about educating ourselves about some little-known Asian subject that had inspired us. Our passionate enthusiasm made us both experts in our respective fields, and we had both gone to great lengths to share our discoveries with others. And then we had both stood by and watched as others sought to profit monetarily from our beloved subjects, resorting to trickery that clouded the field with counterfeits and misinformation.

I focused on my rolling while Roxanna gave a detailed chronology of a Ming dynasty export ban, a centuries-long gap in Chinese trade that caused Southeast Asian cultures to develop their own ceramics. I forced myself to wait long minutes between pipes, hoping to seem interested and not distract her with my greed. When Roxanna had finished her lecture she slowly lowered herself to the floor and placed the folder at the head of the layout tray. “How was that?” she asked.

“Captivating,” I replied. “I just hope there’s not a snap quiz.”

Roxanna smiled. “It needs work, but I’ll be able to polish things up during my flight to Seattle.”

“Would you like me to roll you one?” I asked. “I’m a little rusty but it’s coming back.”

“Sure. I’m ready for one.”

Roxanna then began to tell me about a problem she was having at the museum. It was a recurring dilemma that centered around a colleague of hers—the one who was actively trying to undermine her authority among the museum staff. “He deals in ceramics on the side,” she said.

Roxanna explained to me again about how the vast majority of pieces that made up the ceramics museum’s collection belonged to the founder of Bangkok University. It was a fabulous collection, but the museum founder, like many rich collectors, had become the target of dealers and middlemen trying to pass off reproductions as genuine antiquities. And it so happened that Roxanna’s colleague was one of these.

“He sold some purportedly rare pieces to the founder, some for huge amounts of money. I’m apparently the only one who can see that these ceramics aren’t genuine. They’re copies, but they were very well made and artificially aged. The founder has no idea.”

Roxanna paused as I handed her the pipe. She closed her eyes for a moment after exhaling. I had heard this story a number of times before, but with each telling I was struck by how heavily the dilemma weighed on her.

“These reproduction pieces are now in the museum collection. Well, I thought as long as I can keep them out of sight, it’s not a big problem. But now my colleague is insisting that we display these pieces in the museum right alongside all the genuine ones. This gives him credibility as a dealer. When I wasn’t there he had the staff switch some of the displays around. Can you imagine? I have to deal with this every day!”

There was a sharpness in Roxanna’s eyes that I saw only when she got started on this subject. She was genuinely angry about it. “Things have gotten so confused,” Roxanna said, shaking her head before letting the matter drop.

I thought of the times that I myself had informed collectors of bad acquisitions, and how the news was not always well received. Perhaps I have an oddball way of looking at the problem. If it were me, I would prefer to know that I’d made a mistake so that I could learn from it—rather than having that mistake go unnoticed and perhaps be repeated. For many collectors, however, it seems that ignorance is bliss. In the past I had advised Roxanna to approach the museum founder—the person who had hired Roxanna to be the director—and at least let him know about how her colleague was using her disability against her.

This time I said nothing. I was still preoccupied with my inability to feel the opium. I had smoked another six pipes during Roxanna’s lecture—for a total of ten—and I could now feel only the slightest tingle in the back of my neck. This was way off. At ten pipes after a five-month break I should have been flying. Was it possible that the monastery’s cure had caused some chemical change in my brain? Stubbornly, I kept rolling.

“How many has that been?” Roxanna asked.

“Ten.”

“Oh my. You’re going to make yourself sick.”

“How? It’s having almost no effect on me. I don’t even itch.”

“Why don’t you try some dross? I boiled up a batch a couple weeks ago. There’s a jar of it in my room.”

Dross. I had to snicker. Roxanna had access to the world’s best chandu yet she saved and recycled her dross by a process of boiling and filtering. The result was a jar of smokable black gunk. Willi had always flushed his dross down the toilet, and after my experience in Europe, I’d never had any urge to try smoking it again. Roxanna said hers was “first dross,” meaning it was the residual waste of opium that had only been smoked once. Apparently in the old days there were people who got a third life out of opium by smoking “second dross,” or the dross of the dross. That, however, made no sense to me. The whole idea behind the opium pipe’s unique design and vaporization process, besides preserving heat-sensitive alkaloids, was to remove the impurities and elements such as morphine that put a drag on opium’s lively high.

When it came to smoking pure dross, it was only for the desperate: addicts too poor to afford anything else. In Opium-Smoking in America and China, H. H. Kane tells of a hardcore “opium fiend” in Manhattan who would scrape the dross from pipe bowls and eat it. And Cocteau had this to say about the practice: “The vice of opium-smoking is to smoke the dross.”

“How about this idea?” I said to Roxanna. “What if I take some dross home with me? What would you charge me for it?”

“Oh, I’m not going to sell you dross. If you want it, just take it.”

As soon as I said it, I knew it was a supremely stupid idea. I changed tack: “Maybe I’ll do that during the time when you’re in the States.”

“Okay,” Roxanna said. “I’m leaving in two weeks so we can get together again next weekend if you want.”

The following week I found myself thinking about opium almost constantly. If there had been a way to set the alarm clock for Friday and sleep the week away, I would have done it. Instead I spent my time pondering the events that had brought me to this point in my life—and coming up with reasons to rationalize my return to the opium fold. I decided that it probably all came down to genetics. Not some gene that predisposed me for addiction, but one that hardwired me for collecting and a preference for things Asian. Could such traits be genetically inherited? I knew that some traits, such as being a night owl, were regarded by most people as a matter of temperament. Though seemingly a result of nurturing, my nightly tendency to work into the wee hours came to the fore when I was in my thirties—long after I had left home and was living abroad. During one of my trips to San Diego in the 1990s, I was surprised to learn that I shared this preference for working late nights with my mother. Couldn’t such character traits be genetically passed down from our ancestors, sometimes even skipping a generation or two? And if this was so, I reasoned, why couldn’t my great-grandfather be the source of both my acquisitive and Orientalist tendencies?

I thought of that miniature silk shoe from China that had fascinated me as a child. I had totally forgotten about it when, after having lived in Southeast Asia for over a decade, I flew to San Diego following the death of my grandmother. While paying a visit to my grandfather, I was surprised to see two matching silk shoes in the glass cabinet. My uncle explained that he had found the missing shoe while going through my grandmother’s belongings, and this mention of the silk shoes caused my grandfather to launch into a family history that was previously unknown to me.

He related how his father had once been a “coolie driver”—that was the very term my grandfather used—in California’s Central Valley, the boss of a team of Chinese laborers in charge of digging irrigation canals. Edgar Prentis Martin must also have been a collector of sorts, because the silk shoes in the cabinet were surrounded by a dozen jade miniatures that I had never before seen. The jades had been packed away in a box for decades but, thanks to my uncle, my great-grandfather’s small collection of Chinese antiques was reunited and on display. My grandfather surmised that his father’s curios must have been acquired from his workers, but I thought it more likely that he collected the pieces during trips to the Chinatowns that were once a part of nearly every city and town in California.

Dear old great-granddad. If nobody else could relate to my predicament, I was certain that he would have understood me. Perhaps I was simply following in his footsteps. The difference between us was simple: Early twentieth-century California had exotic adventure at every turn, but I was born too late for that and had to go farther afield. And if the old “coolie driver” had enough interest in the culture of his underlings to acquire a collection of Chinese jades, was it a stretch to think that his curiosity might also have led him to an opium den? The time frame was right. I decided that Edgar Prentis Martin must have been an opium smoker. And if this were so—if great-granddad had indeed kicked the gong around—he, too, would have experienced how opium worms its way into the brain, planting itself deep like an indelible memory. Was it possible then that a taste for opium could be passed on in the genes? I was suddenly sure that it was—and my life was beginning to make sense to me.

Then there was Roxanna. If I were able to do and see half the things she had done and seen since coming to Asia, I might be worthy of holding her opium pipe. The mere act of having a session with Roxanna was one of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences. How did I ever lose sight of that? The pathos that I sensed while in her bedroom that day was nothing more than the melancholia of a mind longing for opium. There was nothing hopeless about Roxanna. She was a survivor. Someone to be emulated, not pitied. A genuine old Asia hand. A role model. Roxanna had come out to Southeast Asia proficient in plucking chickens and was now, due solely to her inquisitiveness and determination, a world-renowned expert on Asian art. Over the thirty-five years that she had been in the region, everything around her had changed, but Roxanna had discovered a private means to escape the boredom and beastliness of the twenty-first century—and I was very fortunate to be in on her secret.

By the time the weekend had arrived, I was convinced. I was in my mid-forties; my youth was finished. Besides my opium experimentation, I hadn’t done anything interesting or noteworthy in years. Paying the bills by writing about my adventures—boating up the Mekong from Cambodia into Laos, or following George Orwell’s footsteps in Upper Burma—was something I no longer had the drive or the energy to do. With the exception of Jake Burton, all my Bangkok journalist friends had long ago left the region, going home to America, Canada, and New Zealand. Tremendous changes over the past decade—especially advances in communications, information dissemination, and air-travel affordability brought about by the Internet—had made it possible for waves of Westerners to come out to Southeast Asia and stay. Being a stranger in a strange land no longer took much effort. Bangkok was teeming with expats, but I no longer knew anybody nor had the desire to make new friends. To me, that now seemed like a young person’s pursuit. Instead, I would take up an old man’s hobby once traditional among the Chinese. Being a devotee of the poppy was the most romantic way I could think of to live out the rest of my life—and now it felt like destiny.

At Roxanna’s I briefly entertained the idea that I might talk her into letting me take some chandu home before she left on her trip to Seattle, but in the end I agreed to take the dross. Due to my past experiences I knew that the high morphine content of the dross would carry a mind-numbing kick, and I was by now desperate to feel something.

Back at my apartment, I spread out the mat and set up my layout tray. It was a real joy to be arranging all the accoutrements as I had done so many times before—guided by the inlaid mother-of-pearl patterns on the hardwood tray. I had left Roxanna’s house after some thirteen pipes, but the buzz was hardly noticeable. I wanted to sample the dross after the slight effects of Roxanna’s chandu had subsided, so I slid the prepared layout tray under my coffee table and waited until midnight, killing time by poking around the Internet.

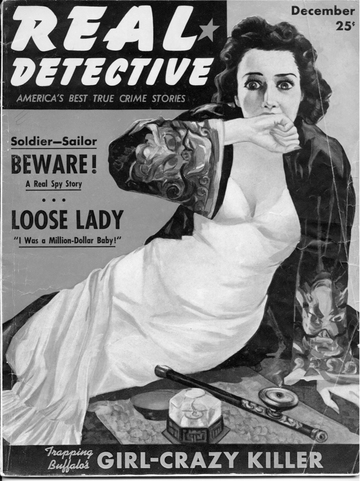

The cover of an issue of Real Detective magazine from 1939. By the time this issue hit the stands, thirty years had passed since America’s nationwide opium-smoking ban was enacted, and its strict enforcement had made the habit increasingly rare in the United States. (From the author’s collection)

At twelve, the neighborhood night watchman’s banging out the hour caught my attention, and I left my computer and brightly lit bedroom for the darkened living room. I pulled the layout tray from under the coffee table and positioned the gooseneck lamp so that its beam made the accoutrements sparkle in the darkness. I placed my Billiken mascot in one corner of the tray and propped up the little framed portrait of Miss Alicia de Santos so that her beseeching eyes were upon me. I fed a Billie Holiday disc into the stereo and turned the volume down until it was barely audible. It was Sunday night—technically just a few minutes into Monday morning—and the river was silent. There were no droning tugs pulling sand barges, no booze cruises entertained by cover bands whose fixed sets played like long, forced encores. Chinatown, nine stories below my window, was absolutely still.

The dross cooked up somewhat like chandu, but the beautiful color and delicious fragrance were missing. There was no golden “hair” produced by pulling the needle over the wok’s inner surface, the cooked opium fuzzy on the tip of the needle like a miniature stick of cotton candy. Instead, what stuck to the needle was a black blob. The dross smell was harsh and reminded me of the burning coal stink that permeates some cities in China. Rolling a dross pill was not unlike rolling opium, except that when heating the pill before sticking it to the bowl, I had to pay careful attention to keep it from bursting into flames and dropping into the lamp. The taste was dreadful, and as soon as I inhaled that first breath through my sugarcane pipe, I knew that smoking dross would ruin the stem’s sweet flavor—seasoned by months of smoking the finest chandu. Despite all this, I never once harbored the idea that perhaps I should stop before I started.

Two hours into the session I began feeling nauseous and decided I had better hang it up for the night. My elaborate preparations to make this experience exactly mirror my pre-detox smoking sprees only added to my frustration—the scene was perfect except for its most important aspect: my being high. If only I could get back to the way it had been. I pushed the layout tray back under the coffee table and went to bed, resolving to try again in a couple of days. The next morning I called Roxanna to complain. She was preoccupied with packing for her trip to Seattle, and I could tell from her voice that she was losing patience with me and my sorry story.

On Wednesday evening—the night of May 7, 2008—I tried again, this time stubbornly rolling until I lost count of the number of pipes I had smoked. When dawn arrived, my head ached and my ears were ringing furiously. I was vexed at having spent another night rolling without reward. I went to bed but could not sleep. Sometime after eight o’clock that morning, I remembered that Roxanna would be at the airport waiting for her flight to Seattle. I sent her a text message: This stuff isn’t working!

She texted me back immediately: STOP!

It was the last time I would ever hear from Roxanna Brown.