David Drake (2009) has summoned us to step into a new level of maturity as an emerging profession, examining broad roots, new research, and best practices that continually build new layers of structure to this field of coaching:

Given the speed and manner in which the field of coaching has grown, it would be risky to assume that the future growth will be either linear or uniform. The field of coaching is, in many ways, an unprecedented phenomenon that requires new levels of thinking about its practices, its nature as a collective, and its priorities as a philosophical and professional force in addressing the unique opportunities of our time. I would contend that the many historical struggles around positioning within coaching must give way to broader and more inclusive approaches to deal with the complex challenges facing our clients, our organizations and our society. If coaching proves unable to adequately meet the rapidly changing needs of our time, it will give way—for better or worse—to other means [p. 138].

Drake’s summons is an important one for this growing profession to heed. It’s the goal of this book to articulate and explore new layers of maturation and sophistication in the growing field of coaching in the hope that the field continues to professionalize itself through rigor and research. The growth of this emerging field has been nothing short of astounding over the past decade.

We begin with a brief examination of what has evolved and changed in this powerful progression toward the professionalization of a new field of study and practice.

The earliest notion of coaching was closely linked to the concept of mentoring. In our first edition of this book, we used the term mentor-coaching and wrote:

Mentoring is the model for coaching . . . but the word mentor is too formal for purposes of a coach training model. I prefer the term coach here. Coach is now applied to a person who facilitates experiential learning that results in future-oriented abilities. This term (coach) refers to a trusted role model, adviser, wise person, friend, mensch, steward or guide—a person who works with emerging human and organizational forces to tap new energy and purpose, to shape new visions and plans, and to generate desired results. A coach is someone trained and devoted to guiding others into increased competence, commitment and confidence [p. 6].

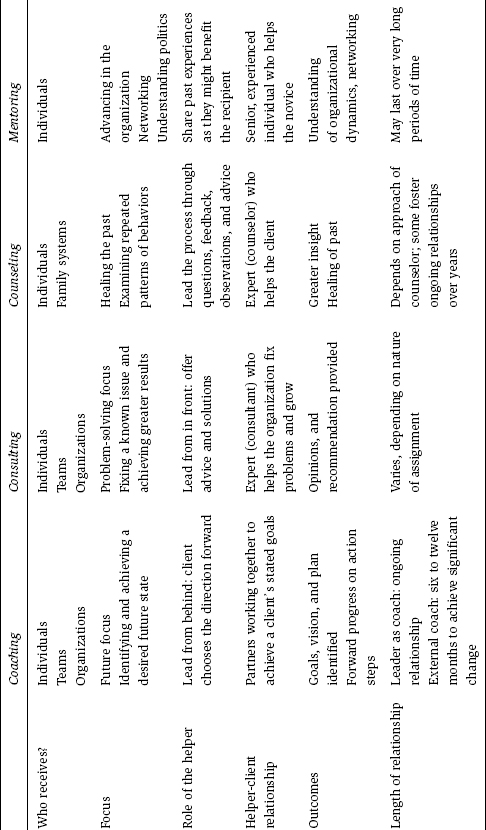

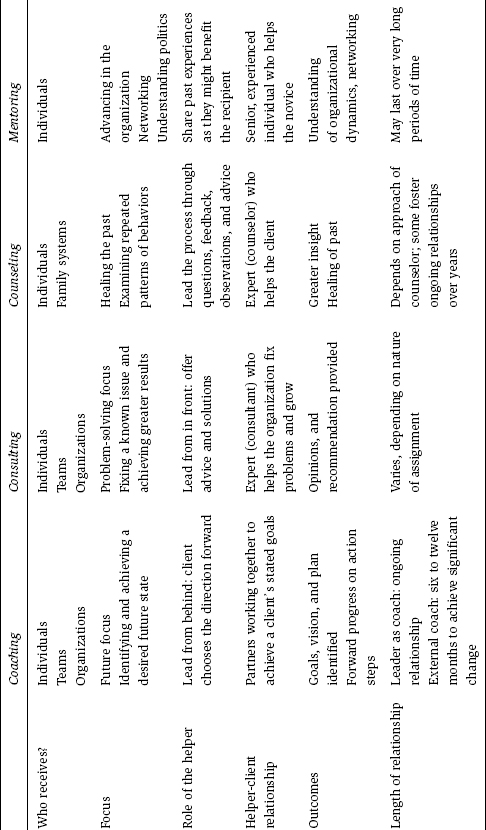

Experience reveals a good deal about the important distinctions and overlaps among the disciplines of coaching, mentoring, consulting, and advising. Mentoring was a natural bridge to coaching, but it offers a limited view of the domain of coaching and the essential elements of the field. Understanding important differences between coaching and mentoring and the distinctions and overlaps relative to the fields of consulting and coaching provides role and boundary clarity for today’s coach. Table 1.1 illustrates some key distinctions between coaching and other practices.

Table 1.1 Coaching, Consulting, Counseling, and Mentoring: Key Distinctions

Although some track the origins to the mid-twentieth century and earlier, most agree little was heard about coaching outside the sports arena until the mid- to late 1980s. Today it is a multimillion-dollar business recognized as an effective way to aid in the development of leaders at all levels in an organization, as well as a means of working with people at normative, predictable life transitions. A quick Web search of the words executive or leadership coaching easily yields over a million sites.

Today there is a blending and merging of the best of the early thinking and increased clarity about what’s essential and what’s peripheral to the field. As it should be, research and practice provide the grounds for studying and testing what works and which theories, concepts, and methodologies need refining.

When the first edition of this book on coaching was written, it was one of only a handful on the market; there were only a few coaching schools, programs, and curricula at the forefront and no professional organizations or alliances. Individual biases and approaches focused on singular perspectives were dominant in the marketplace because little research had been conducted in this new arena. Today these individual biases have given way to important substantive research examining relevant theories and concepts informing this emerging field, as well as a growing body of research studying coaching effectiveness and outcomes in a variety of settings.

In earlier days, there was a widespread belief that the essential coaching skills were readily adaptable to any type of coaching in any setting. Furthermore, it was initially thought that the uses for coaching were nearly limitless. Today we view leadership (at all levels, from emerging to executive) and transition coaching as the two main domains in which coaching exists, all the while sufficiently and ethically managing the boundaries of consulting, counseling, and mentoring.

Coaching skills alone are not sufficient for a coach to succeed in any environment. The range of knowledge, experience, and skills sets needs to be matched to the specialty in which the coach operates. Coaches who enter the organizational domain must understand how organizations work and how systems thinking bears on the work of the individual, the team, and the larger parts of the organization. They must also be sophisticated in their understanding of their role in this system in order to maintain boundaries that allow them to operate effectively as coach.

Early on, coaching was frequently focused on remedial issues, and this mentality still exists in some organizations. However, coaching that occurs in organizations today is most often focused on facilitating the developmental growth of leaders around specific challenges and natural next steps in their leadership role.

At the outset of this emerging field, there was little to guide a coach relative to the impact of the coaching work, and attention wasn’t yet focused on accountability, results, and the overall sustainability of the field. It was simply too early in the development of the field for best practices to surface.

Today good coaches are keenly aware that the sustainability of this emerging coaching field is contingent on the positive results created in the work of coaching with individuals, teams, and organizations. In Chapter Eighteen, on building a coaching culture in organizations, we explore a case study in which issues of accountability come keenly into play as a company attempts to integrate coaching into its culture.

Coaching is now widespread and commonplace, particularly within organizations in the leadership and executive domains, as well as in the transition work of individuals. This is clear evidence of the maturation of the field, and this also signals a more sophisticated consumer of coaching services. Today coaches are more skillfully scrutinized and vetted by organizations and individuals through any series of rigorous processes, including live coaching, references from coaching clients, evidence of coach training and certification, and years of relevant experience and background.

The expectation is that coaches will be able to provide evidence of the impact of their work—that is, the return on investment must be clear in today’s marketplace. The case vignettes on Sarah in Chapter Eleven highlight this link between client goals and the overall needs of her team and the organization.

The theme of change has been an important factor in the emergence of this field, and this perspective is even truer today than it was in the 1990s. Today change has become the most dependable reality in our lives and in our world. People and organizations around the globe live with continuous uncertainty, tentativeness, and a sense of growing unpredictably. Many have no long-term expectations and plans and simply strive to keep pace with intense daily and weekly schedules of demands and responsibilities with little sense of a long-range plan for the future.

This reality was not true for most of the twentieth century. The world then seemed fairly dependable, uniform, and evolving, and lives took on those dimensions. The professions were organized around the assumptions of a stable culture of perpetual progress, central authority, and control, and there was a trust and a willingness to follow the overarching cultural rules.

Today’s world is turbulent, unpredictable, and increasingly fragile. Organizations are operating in a continual state of change, and workers and leaders alike must be agile and skilled at managing transitions and challenges in order to thrive in the evolving marketplace.