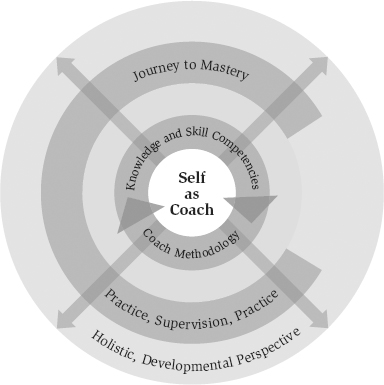

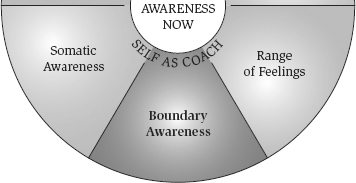

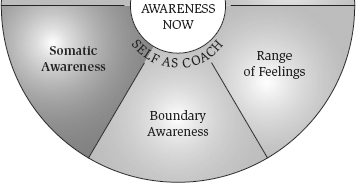

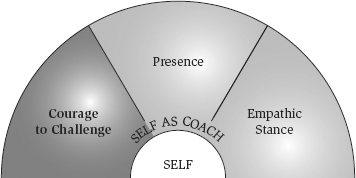

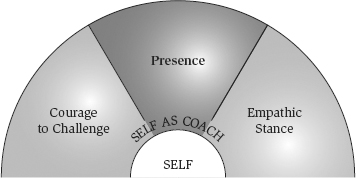

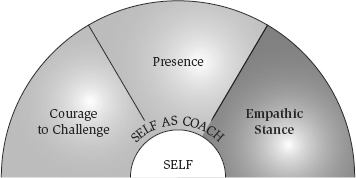

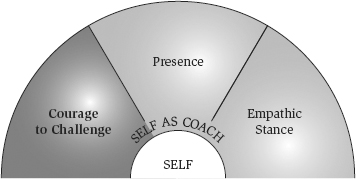

Figure 4.1 The Elements of Masterful Coaching

© Hudson Institute of Santa Barbara.

Current coaching literature affords surprisingly little attention to an essential dimension of coaching: self as coach, that is, the ongoing inner development of the coach required to build broad capacity and work effectively in an assortment of settings with a variety of clients. This chapter takes a close look at all this entails.

Masterful coaching is a fusion of several essential elements, and no one factor is enough alone. The essentials we are most familiar with include a broad knowledge-based set of competencies in theories and concepts that are both seminal and evidence based, a strong skill-based set of competencies aligned with the work of coaching, and the understanding and ability to operationalize a coaching methodology that spans the first interview to the conclusion of a coaching engagement. Yet this list of basic ingredients is insufficient. A coach must be equally prepared to examine the inner landscape of self-development in order to build capacity. This development work is perhaps the hardest for both coaches in training and coaches in practice because it is forever unfolding, always humbling, and at times quite complex and demanding territory.

The capacity of a coach to practice adeptly is limited and defined by the coach’s understanding and development of the inner workings of self and the ability to take full advantage of the use of self (that is, undertaking actions that stem from complete self-awareness). We build capacity as coach when we are able to step back and observe our self in action and open the door to new choices. Robert Kegan (1982) might capture this by posing that “we have object while we are subject” (p. 32). Kegan’s use of subject refers to ourselves, including our unexamined beliefs and ways of being in the world that we cannot see when operating from this place, while our ability to step back, see, reflect on, and be responsible for all of who we are is “object.” The subject prompts us to act, but our way of being is often so ingrained that we cannot observe it or reflect on the action required. The object stance allows us to take a step back and observe and reflect on our self, including our unexamined beliefs and ways of making meaning in our world. This is what we as coaches help our clients do. The fullness of this continually unfolding dance between subject and object in coaching is made richer by how well we, as coaches, cultivate this same ground in our own self-as-coach domain.

As always, we must start with self. A coach can’t explore realms of self with a client when she hasn’t yet examined this domain for herself. When a coach hasn’t accessed her own feelings of anger or explored her sense of inadequacies or other faults, she will find it difficult to notice and create space for this exploration with her client. When a coach has explored little about her own emotions, it follows that her ability to notice the presence or absence of feelings in the client will be limited. The coach’s willingness to enter the emotional terrain is limited or served by her own attention to work on self. This means a masterful coach is regularly tilling the soil of self-exploration and developing her own inner landscape, which maximizes her ability to move into important client explorations with agility and ease.

Figure 4.1 portrays self as coach as central and pivotal to masterful coaching with a direct impact on the coach’s ability to incorporate skill- and knowledge-based competencies and effectively use a sound coach methodology. The outer rings of coaching practice and journey to mastery are supported by these inner domains, and the upper limits of one’s capacity are guided by the innermost circles, which are foundational to the other key elements present in masterful coaching. To date, the field of coaching places notable emphasis on both skill-based competencies and, to a lesser but growing degree, knowledge-based competencies. But it provides insufficient emphasis on understanding the inner dimensions of the self-as-coach domain as central in supporting all of the other key elements.

Self as coach connotes the work of developing our inner landscape: habits and behaviors, long-held stories, and our ways of making meaning and living in the world. This internal territory has been well researched by the field of psychology and to some extent in the organizational and leadership development arenas. These fields of study provide key models and frameworks shedding light on various aspects of this domain, and the chapters in Part Three provide a more thorough examination of the foundational theories supporting self as coach.

A well-known model that captures the complexities of self as coach can be extrapolated from Karen Horney’s (1945) work on the basic neurotic conflict. She conceived of three basic (“neurotic” in her terms) coping strategies for managing conflict. Although her emphasis was on the examination of the more deeply psychological realms of the neurotic, an adaptation of Horney’s model of the three coping strategies in normal human beings in Figure 4.2 provides a fascinating perspective into the complexities of the developmental terrain of self as coach. This reworking of Horney’s well-known work provides a macrolevel framework for building coaching capacity. While Horney specifically suggested that the neurotic develops a comfort zone and makes a home base in predominantly one corner of the triangle (moving against, moving toward, or moving away), this same pattern of coping strategies is quite adaptable to normal human functioning well in the world, as coaches do.

The three strategies provide the coach with a view of one’s most familiar and perhaps dominant stance. In Figure 4.2, each corner represents one’s home base likely developed in our early years and supporting our stories about how the world works and how we need to continually adapt in order to live safely in it today. This is self-as-coach terrain at a macrolevel. A coach can’t operate at a masterful level unless she is able to exercise agility and shift from one stance to another in order to operate effectively with a client. Consider this adaptation of her three stances as they pertain to the use of self for the coach:

This adaptation of Horney’s model emphasizes the importance to the coach of knowing her own strengths and limitations. Identifying our own comfort zone provides rich information about our own story and potential limitations, creating a launching point from which to extend capacity into all three parts of this triangle.

As we proceed to examine the main goals and target behaviors a coach strives for in developing in the self as coach arena, the broad behavioral groupings and the inherent internal challenges that Horney proposed prove to be important and recurring threads of valuable support to the coach.

Most professionals come to the practice of coaching following a long and successful career in leadership and professional practice, from senior leaders and CEOs to executive directors of nonprofits, lawyers, physicians, business owners, career professionals, and more. The predominant belief is that what’s required to be a great coach is largely about building a tool kit of techniques, approaches, assessments, and reading resources that will help the coach solve the client’s problems. Most leaders initially find it difficult to understand that the most important tool is their own self. What’s more, the work of the coach does not primarily involve solving problems for one’s clients. The reality that the work of a coach is fostering transformative change that happens from the inside out and requires the coach to connect the head and heart of the client is counterintuitive for most of us. Yet in order to help clients make the real shifts they desire and create lasting change, coaching requires a much more robust approach than providing advice. The self-as-coach domain emphasizes the coach’s ability to use self as an instrument of change. This is central to delivering lasting change and demands a continual examination of the intrapsychic workings of the coach.

Most of us can likely scan the past few days and identify a conversation or two where something didn’t go as we had intended. Often our conclusion is that it was someone else’s fault. We typically look outside ourselves before reflecting on our own role. Now consider a client who does this consistently: every difficulty in the client’s life is someone else’s fault. To notice this pattern requires careful listening and full presence; to use self as instrument requires the coach to share this observation and challenge the client’s thinking. Consider another client who wants to develop the trust and respect of his team, and each time he comes to coaching, he arrives frazzled, apologizing profusely about being ten or fifteen minutes late for the session yet again. The coach skilled in using self as instrument is adept in bringing this up with the client by sharing how it affects the coach and finding out if the client is aware of this impact and if this behavior may in fact show up with others, especially members of his team.

The coach’s ability to use self as instrument in this way creates the possibility of powerful breakthrough moments that connect the client’s head and heart to some of the very changes he wants to make. This experience anchors a deepened awareness of the change.

Truly masterful coaches routinely engage in examining their own inner landscape, exposing and understanding their feelings, and sharing their struggles and questions with other peers. There is not a sense that “I’ve arrived” with a master coach; instead there is a fierce commitment to staying on a development path that seeks to continually expand one’s capacity as coach and engage one’s compassion and respect for how challenging it is for anyone to tackle an important change.

The framework that follows offers a sense of what constitutes this self-as-coach dimension, the pathway for a coach in this domain, as well as some of the models, tools, and resources that can support this development.

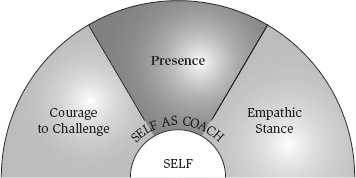

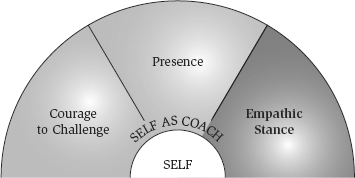

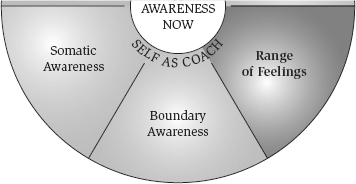

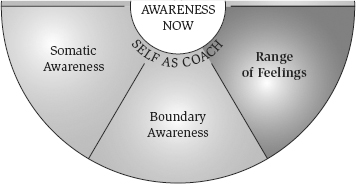

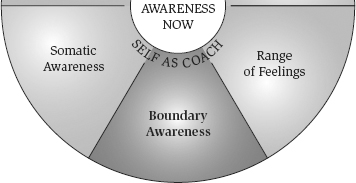

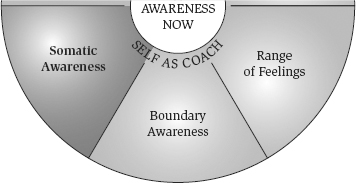

Our inner landscape is complex territory, and while the areas of personality development and intrapsychic dynamics are beyond the scope of this book, it is important in coaching to focus on a basic framework of key elements that comprise the domain of self as coach. This framework (Figure 4.3) is where we start in building our capacity to work with any variety of human challenges using our self with intention and maximum effectiveness and maximize use of coaching skills and techniques.

The domains (resources and exercises for each of these domains will be examined at the end of this chapter, in “Six Reflective Practices to Strengthen Self-as-Coach Capacity”) in the self-as-coach framework are presence, empathic stance, range of feelings, boundary awareness, somatic awareness, and courage to challenge. Of course, no one will be able to operate with full awareness in each of these domains at all times. Life doesn’t happen this way; even the most skillful coaches will experience a loss of boundaries, a lack of empathy at the right time, a loss of awareness of their somatic being, or the courage to challenge when it’s most important. Yet this model provides a way of scanning the inner landscape to determine what’s most needed with the client and with one’s self at any given time, and it provides a map for the coach’s own developmental journey toward mastery.

Tolbert and Hanafin (2006) describe presence, a complex blend of unique qualities, as “the use of self with intention—selectively using one’s awareness to advance the work with the client” (p. 72). Halpern and Lubar (2003) offer a definition equally well suited to the coach: “the ability to be completely in the moment, and flexible enough to handle the unexpected” (p. 9).

There are many nuances to understanding precisely what this concept of presence entails, but for our purposes, what’s most essential is the ability to be fully present and engaged with the client in the moment and alert to all that is happening in the session at several levels: what’s being said, what’s not being said, what’s being acted out, what’s observable somatically, and what’s a pattern that you’ve observed before, for example. Full presence is a practice that requires time, attention, and continual development.

We can easily identify signs of the coach who doesn’t exhibit presence: the coach who slips into the session just a moment or two after completing an important phone call, or a coach who arrives with a burning unresolved issue, or an unmanaged inner critic at work. In each case, the coach is operating with a diminished presence that compromises the quality of what’s possible in the work with clients.

The coach’s ability to experience and convey empathy is a pivotal element in this work. One’s capacity to walk in the shoes of another and experience the feelings of another defines empathy. It doesn’t require a lot of words, but it does necessitate that we notice the feeling state of another and convey that we see him or her in this state and are at home in this space with the client. A client quickly discerns when a coach is not able to connect with a feeling state and see the individual, and this rapidly diminishes what’s possible and what surfaces in the coaching engagement.

A coach can choose to notice and acknowledge tears or quickly move to get the box of tissues and “help the client feel better.” Empathy and noticing the tears is helpful to the client, whereas rushing to the client’s aid in an effort to help the client “feel better” or sympathizing and soothing the client results in entering the client’s system, losing effectiveness as coach, and, most important, missing the power of the moment for the client. Boundaries are important in this domain as well. If the coach’s boundaries are too diffuse, the empathy will likely bleed into sympathy, and the coach’s ability to fully observe will be diminished.

A coach needs to have access to a wide range of feelings and ease in exploring and experiencing a full scope of emotions in order to allow the client’s emotions to surface and get used effectively in coaching. The coach who is at ease with her own feelings will notice them in the client and make space for these feelings in the coaching work.

The coach who is uncomfortable with a particular feeling will likely move away from it or avoid it entirely if it surfaces in the coaching work. The coach who has a limited range of feelings will likely miss the opportunity to attend to the client’s feeling states when it’s important. Whatever the client’s emotional reaction or state might be, a masterful coach wants to be able to create a safe place for a range of feelings and use them on behalf of the client when appropriate. This ability to connect to the client’s feelings and create a space in which the client is comfortable exploring the emotional terrain and developing new insights leading to new actions is essential in coaching.

The work of Murray Bowen (1978), a psychiatrist and early family systems therapist, is seminal to understanding the concept of differentiation and boundary awareness in our lives. He taught us that the less differentiated we are as human beings, the more likely we are to engage in an endless stream of third-person conversations in order to avoid the direct conversations we need to have with someone. This is particularly relevant for a coach because the tendency to discuss a third person within the coaching engagement almost always arises.

It’s easy to get drawn into the system of another, whether it’s an individual client, a team, or a larger organizational system. It requires a coach’s careful attention to boundaries in order to notice this dynamic, manage himself, and attend to it effectively. When working with coaches, we often draw an imaginary line on the floor with very tight boundary management at one end and diffuse and highly permeable boundaries at the other end. We ask coaches to place themselves on this continuum and then talk about the upsides and downsides of their location. Coaches on the diffuse and permeable end notice that it’s easy to get drawn into the client’s world, the client’s needs, and the client’s feeling state and render it difficult to step back sufficiently to allow clients to notice their own dynamics. Those with tight boundaries notice they may be too hard to penetrate at times, and it may be difficult for the client to feel fully connected and safe with the coach. Boundary awareness and management requires an astute and highly observant coach to walk this line and remain fully effective in the work.

Experts in somatic work remind us that every action originates in the body, and when we fully engage the body in supporting changes we want to make, we increase the likelihood of lasting change. Noticing how we physically hold ourselves shapes our presence and our state of mind, and this level of somatic awareness can help shift a coach to a more effective stance. A coaching colleague reflects on somatic awareness in this way: “I notice that when I reach down and rub my lower legs or squeeze my knees together, I am feeling like I’m in uncomfortable territory and I start to become more tentative with my client. When I hold my posture steady, keeping my feet on the floor and relaxing my hands, I am more present and focused with my client.” If a coach wants her clients to experience her as warm and inviting and yet her face is almost always stern with a frown and furrowed brow, her facial expression can be the starting point for a deeper shift. Noticing how our clients present themselves somatically can allow us to make observations that become helpful and meaningful to those clients relative to their coaching goals. For example, if a high-level leader wants to feel confident about his abilities and yet his posture is noticeably slumped, the coach’s ability to share this observation can result in a shift in posture, which will create a somatic trigger to support a much bigger change.

This domain is paramount in coaching. Clients don’t come to us looking for a friendly chat or an agreeable shoulder; instead they arrive wanting to make a change they have been unable to attain on their own. And like all of us, even when the client is seemingly committed and clear about the change, obstacles quickly and predictably surface. The skill of challenging a client at the right time is vital in masterful coaching, and the strength to share an observation even when it’s a little uncomfortable is essential. Yet many coaches find this territory personally onerous. It may be a wish to stay on the positive side, a desire to remain on the supportive side, or a general uneasiness with more difficult conversations that keeps a coach from entering this important territory. In reality, the coach’s ability to view challenging, sharing observations, and providing feedback as critical to facilitating the change the client wants is the hallmark of mastery when coupled with deep trust and respect.

Consider the client who comes to a coach with a goal of strengthening her leadership presence among peers, direct reports, and the senior team. Session after session, the coach observes that this client routinely apologizes to the coach for her smallest comments, using a voice that is almost difficult to hear at times and exhibiting a posture that exudes a lack of confidence. Or the client who wants to create stronger relationships with members of her new team, and you observe a facial expression that includes an almost continually furrowed brow and a slight frown. Or the client who wants desperately to figure out how to get into the job market, and every other sentence is, “I just have bad luck.” In most coaching situations, there is a strong connection between how the client appears during sessions and the goals he or she is working on. It’s the work of a coach to surface these observations, link them to the goals of coaching, and help create enough awareness that the client is able to make important choices that may have a big impact on next steps.

The coach who fails to address these in-the-moment opportunities, or as Doug Silsbee (2008) aptly phrases it, “catch a habit in the act,” does the client no favor. Instead, the coach is likely bypassing the opportunity because she has not built sufficient capacity in the self-as-coach domain.

The situations that follow present a series of common coaching vignettes and challenges. The vignettes are meant to nudge your own self-examination more than provide an exhaustive inventory of coaching challenges. Chances are some of these scenarios will resonate more or less with any coach and provide ample ground for further exploration.

Jane has operated a successful business for many years but admits that she has always found conflict uncomfortable. She works to help people feel at ease and does what is required to lighten up a situation when it gets heated. This has been her modus operandi for thirty years. Now she is moving into the world of coaching, and this dynamic becomes a limiting factor. She notices that when her clients begin to express anger or get upset, she is quick to try to soothe the client or divert the conversation to more comfortable territory. In the past, Jane hasn’t paid much attention to the conflict-averse habit she has, but now, as a coach, she understands how important it is to build her capacity on this front.

Conflict naturally shows up in the coaching engagement; sometimes there is tension between coach and client that needs to be surfaced and explored, and at other times conflict arises for the client relative to the changes he or she is committing to. It’s hard to avoid this: conflict is a part of life, and if Jane is unwilling or unable to enter that space, she limits her capacity as a coach to fully explore all of the dynamics at play in an engagement.

Bob has been a successful member of several senior leadership teams over the years, and his track record is impressive. However, as he enters the work of coaching, he admits that feedback has always made him uneasy. He has a tendency to sugarcoat, glossing over areas that others might address and to overlook some behaviors because of his own discomfort. Now he finds himself in coaching engagements where providing clear feedback and sharing observations with the client are clearly important in order for clients to make the changes they want.

Feedback is an integral part of coaching throughout the process. A coach needs to elicit feedback from others (boss–coach–human resource partner and client conversations, and in stakeholder interviews, for instance) in order to work effectively with leaders inside organizations. A coach needs to deftly and routinely provide observations and feedback to clients about behaviors, patterns, and observations that will be helpful, albeit temporarily uncomfortable for the client. Unless Bob works his inner terrain and unpacks his obstacles to providing feedback, this will be an enormously limiting element in his coaching.

Mary has a stellar track record as a strategic thinker in the world of mergers and acquisitions. She comes to the work of coaching with a strong understanding of what it takes to be a great leader and a clear grasp of the intricacies of organizational systems. But Mary is the first to admit that feelings are uncomfortable territory for her. She isn’t well versed in her own feelings and works to stay out of others’ feelings. In fact, when she came to coaching, she didn’t see feelings as the work of a coach. Yet over and over in coaching engagements with healthy, committed clients, feelings show up, and she knows she needs to make adjustments in herself in order to meet these feelings, hold them with a client, and open the door to exploration of the feelings.

Feelings are a natural part of a whole person. Whether coaching a leader who wants to strengthen her presence, a manager who wants to learn how to delegate, or an individual building a postwork chapter, feelings are an important dimension of the coaching work. Change happens in the melting pot of emotion, cognition, and relationship. Mary needs to start by exploring the inner terrain of her own feelings before she can be comfortable working with a client’s feelings.

John has been a fast-moving, successful executive for years, with plenty of accolades and a hefty track record to prove it. He comes to coaching believing this will be an easy transition. Yet he has a certain intensity about him that manifests in a strong, sometimes loud voice, a tight torso that is always leaning forward, and a rapid pace that is almost palpable for anyone in his vicinity. All of this likely worked in his previous career, but it’s now an impediment in the work of coaching.

Understanding one’s impact on others is central in working with clients. It’s hard for a client to connect with a coach if the pace and intensity are barriers. An inability to fully connect with the client will be enormously limiting for a coach and the prospect of building a coaching practice. John will need to elicit feedback from others on his impact and then build some methodical practices that will support him in changing some of these long-standing habits.

Laurie came to coaching with a long list of accomplishments as a leader in the nonprofit sector. She has been in the role of executive director in more than one organization and is sought after by many boards. She’s now ready to shift gears and provide much-needed coaching services to leaders in the nonprofit realm. Laurie has a no-nonsense approach to life and admits that work has been the primary driver in her world for the past thirty years. Her biggest challenge (when she’s willing to examine it) is slowing down and creating space for something other than work in her life. She’s had only a modicum of success on this front, and it has been in small fits and starts. As she moves into coaching, it is becoming clear that her well-honed rapid-fire pace is an obstacle to deep listening and full presence with her clients. Her style of interrupting conversations, talking over clients, and watching the clock shows up in her coaching and creates barriers she needs to address.

Laurie wants to get from start to finish as quickly as possible in an effort to deliver value to the client. But this approach does not allow the client to do the deeper work that builds a foundation for meaningful and sustainable change to unfold. When Laurie had the experience of three clients canceling and discontinuing the coaching work with her, she knew it was a signal about her, not her clients.

Our pace is a way of being that is hard for most of us to notice, and it’s an area that others are often reluctant to provide candid feedback about. Laurie needs to slow down and take the time to become perceptive to her clients’ needs so she can make the important connections they need her to make. She can take on practices and routines in her personal life that provide more grounding and calming and involve greater reflection. She can begin by gaining feedback from those close to her in order to make adjustments where it’s most important for her.

Marcia admits she gets uncomfortable when a client seems unhappy, ill at ease, or near tears, and her first response is reassurance. She believes this has worked well in her long list of impressive leadership roles, and she brings this same perspective to coaching. Yet through both peer and supervision feedback, she begins to notice that her quick move to reassure a client, grab the box of tissues, or give the proverbial pat on the back robs the client of important moments of exploration.

Reassurance promotes comfort, not change, and while there is a time and place for it, reassurance is seldom the dominant approach that will facilitate lasting change. In fact, reassurance ill timed will prevent the client from facing important work in coaching. If a client tells the coach he received some tough feedback from his boss that felt hurtful and the coach moves to reassure the client, the real work of unpacking the interaction and examining how the client wants to address this are lost. Marcia can begin by noticing how often she moves into caring mode in her conversations. Journaling or creating a daily log may be a support. Gaining feedback from those close to her will also provide important perspective about the impact her singular approach has on others.

Mike is a pro. He has headed up successful sales teams at the highest levels in a series of prominent organizations, and his track record is one that others covet. He’s passionate about coaching sales leaders and knows he can make a difference, but each time he sits down to engage in a coaching conversation, he can hear a voice on his shoulder second-guessing him, doubting his abilities and making it difficult to be at home in his own skin as a coach. He finds himself getting nervous before each coaching session and conducting a postmortem analysis about every little thing he might have done better as a coach.

The inner critic that Mike carries with him will limit his ability to be fully present with the client and coach effectively. Mike is aware of the critic, and that’s a great first step; now he needs to attend to his work on self and develop a practice that will allow him to shed enough of the inner critic and develop sufficient compassion and support for himself to be fully present and powerful as a coach.

It’s impossible for a coach to uncover the intrapsychic dynamics or the inner landscape of self without the support of others, accompanied by a regular practice heightening awareness of what’s at play inside that is contributing to behaviors that show up outside. The coach committed to this pathway needs to invest in both approaches: building a regular practice that cultivates an inner dialogue and engaging with others in seeking candid feedback, input, and support on this path.

Armed with a regular practice and the support of trusted coach colleagues on this journey, where does a coach begin? The areas of exploration for our own growth and development are endless, and it’s important to remember it’s a journey. We engage in continual development of our self in order to build capacity to be sufficient as a coach and deserving of the opportunity to sit in this role with another human being. Cultivation of the inner landscape ought to be one of the most important precepts in coaching.

Table 4.1 provides a starting point for the coach to examine the self-as-coach domains, highlighting the desired stance of a masterful coach, the natural traps, and a closer look at some of the nuances of each domain. In addition, a thorough set of practices and resources for supporting development in each self-as-coach area follows.

Table 4.1 Self-as-Coach Continuum of Learning

| The Optimal Stance | The Trap |

| Full presence | Sidetracked, distracted, absent |

| • In the moment | • Distracted |

| • Centered, engaged | • Unbalanced |

| • Present to notice patterns | • Mechanical and rigid |

| • Unable to discern patterns | |

| Empathic stance | Sympathetic or disconnected |

| • Empathic listening | • Listening to solve |

| • Unconditional positive regard | • Missing important client signals |

| Range of feelings | Moves away from feelings or overindulges in emotions |

| • Access to full range of feelings | |

| • Limited awareness of feelings | |

| • Inappropriate response to emotional context | |

| Boundary awareness | Fusion or collusion |

| • Maintains independence | • Plays role of go-between |

| • Discerns important boundaries | • Does work that belongs to client |

| • Understands systems thinking | • Becomes mediator |

| Somatic awareness | Misses using body cues |

| • Uses own physical self to support effective coaching | • Inadvertently projects inconsistent messages |

| • Notices revealing patterns of client | • Misses internal signals |

| • Overlooks important client signals (for example, sitting on hands, tapping fingers, frowning, laughing when sad) | |

| Courage to challenge | Plays it nice, polite, or safe |

| • Challenges thinking patterns | • Holds back for fear of offending |

| • Shares observations | • Holds back because it’s uncomfortable |

| • Shares feedback | • Unwittingly supports status quo |

The contents of Table 4.1 represent a continuum of learning rather than an either-or dichotomy; setbacks are predictable and typically lead us to greater advancement of goals with awareness and a willingness to change. The goal is what a great coach continually strives for but can never expect to fully attain because there is always something to be learned. The trap is what a coach seeks to avoid and what leads to coaching work that remains less effective and sustainable over time.

Reflection practices are pivotal in the pathway to change. They help a coach gain a new level of awareness about a specific way of being or a behavior that is crucial in the pathway to change. The self-as-coach stances outlined in Table 4.1 are within reach when the coach spends time linking helpful models and tools to regular practice. In the sections that follow, each self-as-coach domain is linked to theories and models that provide more understanding of the stance, followed by practices a coach may consider in strengthening one of the areas of development.

Doug Silsbee (2008) defines presence as “the most resourceful, ready, resilient inner state available to us at every moment” (p. 13). Halpern and Lubar (2003) define this concept as “the ability to connect authentically with the thoughts and feelings of another” (p. 3). In both definitions there is an emphasis on the quality and readiness of one’s inner state that allows one to be authentically present in the here and now with a client.

Good coaches know that what sounds simple takes a lot of attention to cultivate, and nowhere is that truer than in the development of presence. The impediments to our full presence are mighty forces: our habits, our ego, the board of directors in our head directing us, and more. Full presence is intimately linked to cultivating our inner landscape. Without an inner dialogue and an awareness of the internal chatter, presence is impossible to achieve.

An important by-product of full presence is the heightened ability of the coach to view the larger context of the client and hear the nuances of patterns and stories that the client is living in. The fully present coach hears, reads, and perceives the client on many levels, including the literal words, the metaphors, the emotional terrain, and the somatic manifestations. Halpern and Lubar (2003) also emphasize flexibility as a key element in presence: our ability to respond in the moment relative to what the client is presenting us.

Consider this coach’s situation. Janet combines her coaching work with consulting and spends about 60 percent of her time on the road for her work. That means a lot of time on planes, in airports, and in hotels and constantly shifting time zones. Her life is fast paced, and it’s not uncommon to find herself managing travel delays and shifting schedule challenges. Although it’s not impossible for Janet to hone her ability to be present at any given moment in the midst of her day-to-day work routines, it surely requires a fierce commitment and practice on her part. Otherwise the demands of her lifestyle will inevitably intrude on her ability to authentically connect with a client in the midst of one of her fast-paced days.

Noticing patterns and themes is an ability heightened by the full presence of the coach. Books have been written on this important topic, so this brief description and examination only skims what’s important. In the early stages of development as a coach it’s easy to get drawn into the details of a client’s story and believe the work of a coach is in understanding all of the details. In fact, the real work of the coach is not in the sordid details of a situation, but in the ability to notice patterns in the client’s stories, pay attention to the language of the client, and uncover the world as the client sees it and the limiting stories the client exists within.

Otto Laske (2006b) writes of the “FoR,” that is, the frame of reference of the client that ultimately determines his or her behavior: “Behavior is shaped by how one makes meaning and sense of the world and this defines their ‘FoR.’ The work of noticing the client’s FoR requires a well-honed ability to listen to and pay attention to the patterns, stories and essence of the client’s words and the courage to surface this deeper layer of the coaching conversation” (p. 45). James Flaherty (2010) provides a similar perspective in his use of the concept of the structure of interpretation and writes, “Each person’s actions are fully consistent with the interpretation he brought, an interpretation that persists across time, across events and across circumstances” (p. 8).

What is required in order for a coach to pay attention and tease out the client’s story, frame of reference, or structure of interpretation is presence to one’s client and presence to one’s self. As always, a coach must start with work on self that uncovers one’s own stories, one’s own particular structure of interpretation. Once a coach has begun to uncover this for herself and is able to observe how this bears on her own life, she becomes attuned to noticing this in others.

Building presence as a coach includes multiple layers, and the first step is the work of managing distractions before, during, and after a coaching session. Consider using the following three steps with each of your coaching engagements over a thirty-day period, and pay attention to how deliberate reflection supports and deepens your presence as a coach:

Exercises for Deepening the Ability to Notice Patterns.

Reading on Presence

Empathy, the ability to perceive the feelings and experiences of a client and communicate this to the client, requires skill, practice, and awareness.

One of the big challenges for coaches is caring too much and wanting one’s client to feel better now or wanting to spare the client needless suffering. It may seem counterintuitive, but it’s a well-documented fact that one thing a client needs is just enough tension and discomfort in the coaching engagement to create new awareness that will lead to exploring new ways of being. If a client expresses sadness and hurt during a session and begins to cry, the coach can send an empathic signal that demonstrates a connection and caring through a word or two or perhaps a facial signal. If instead the coach moves toward the client with tissue in hand, it conveys a message, “Oh, how can I make you feel better right now so that feeling goes away?” The urge to be sympathetic and soothing moves toward colluding with the client in an effort to protect the client from something uncomfortable that’s emerging, often in the form of feelings. To the extent that the coach has a limited range of feelings that are comfortable, this has a direct impact on the client.

Bill, a client, shares his deep fear of standing up in front of a large group and making a presentation and his coach, John, responds with an empathic stance: “I get that; it can be a tough challenge.” If instead he moves to a sympathetic response, he might say, “Boy, do I understand this one. I’ve struggled with it myself, and I have a lot of memories of a whole lot of anxiety and perspiring before those sorts of presentations. I learned a few things I think could be helpful for you.” Once John shifts from the empathic stance to the sympathetic one, he loses his ability to view the client’s needs, feelings, and experience objectively.

The pull to collude with the client is often prompted by a coach’s unaware desire to please the client, be liked by the client, care for the client, or manage his or her own discomfort with certain feelings and situations. When this collusion occurs, the boundaries of the coach become blurred, and the coach enters into the system of the client instead of observing the client’s system, holding a firm boundary and conveying the empathic message, “I care, I see you, I am here,” without getting entangled and playing a part in the client’s well practiced story.

Empathic listening is another element in the empathic stance. The work for any coach in developing empathy requires an ability to self-manage her own internal dialogue as a conversation develops, suspend judgments and solutions, and listen to what this means to the client. This requires the coach to notice her own emotional cues and states. Given what we understand today about how our limbic systems work, the coach’s emotional cues provide clues about the client’s state as well. Second, an empathic stance demands deep listening on the coach’s part in order to fully understand what the client’s story means to the client, all the while resisting the urge to shift to one’s own interpretations, judgments, or potential solution-building efforts.

Chris Argyris’s (1982) well-known model, the ladder of inference (Figure 4.4), provides a helpful map into the intricacies of our fast-paced internal dialogue. He provides an illustration of how quickly a coach can shift from listening and empathizing with the client’s experience to instead responding and reacting through her own set of assumptions and biases. The ladder of inference provides an easy way for a coach to track her own thinking and inner experience and make it more conscious. Choice comes from awareness, so once we’ve become conscious of biases, assumptions, and meanings that limit our ability to connect with another and hear another, we can more freely make new choices.

One of Argyris’s (1982) interesting findings is that the more experience we have in life, the more likely we are to hasten the speed of each successive trip up the ladder of inference. In other words, the well-practiced individual relies on certain assumptions based on years of experience. These assumptions cut one off from critical information and likely decrease our empathic response.

Translate a “quick run up the ladder of inference” to the work of a coach, and it quickly becomes problematic. John, the coach, meets a client for the first time and throughout the exploratory conversation notices that the client is quite quiet and a little passive. Based on some experiences with clients who weren’t very engaged in the coaching work, John quickly leaps to the conclusion that this client isn’t ready to engage in the serious work of coaching. Judy is working with a client who is constantly fidgeting during the coaching session: moving and tapping his feet, clicking his writing utensil, at times tapping his fingers. She makes a rapid trip up the ladder assuming (without checking) that he is impatient and restless about their coaching work. In fact, when Judy finally musters the courage to share her observations, her client gets a little teary and tells her about his long-fought challenges with attention deficit disorder. Our empathy is ignited when we connect with our client, and ultimately this requires managing our own stories, life experiences, biases, and assumptions.

Argyris’s model is a helpful tool for coaches to track their own ability to stay close to the bottom of the ladder where their biases, experiences, and beliefs are held at bay and self-managed in order that they stay focused on what is observable in the present with the client. When the coach hones in on this important observable territory, it’s possible to provide critical information to the client through the sharing of observations in the moment and often creating a powerful breakthrough experience for the client. For example, the coach could notice that her client smiles almost continually throughout their session, whether the conversation is difficult or easy. If the coach climbed up the ladder, she might infer that the client is very uncomfortable with feelings and trying to keep things superficial. But instead she simply shares her observation (bottom-of-the ladder information): “I wonder if I might share an observation I’m having. We’ve talked about some very difficult situations for the past hour or so, and your facial expression has continually maintained a smile, even when we were discussing some very sad things. I wonder if you have any awareness of this? The impact on me is that I find myself wondering what’s happening inside you.” Or perhaps she notices that the pace of her client’s speech is so rapid that it’s hard to discern each word at times. Instead of making assumptions about the rapid-fire approach, she instead shares her observation (bottom of the ladder): “I want to stop you for a moment and share something I’m noticing: your speech pattern is so fast, so rapid, that I have to work very hard to catch each word, and I often miss some. I wonder if you have any awareness of this?”

The ability to stay at the bottom on the ladder overlaps and requires some of the other essential self-as-coach stances, including a deep presence, respect for the client, and courage to share important observations with the client.

One of the helpful tools for a coach to strengthen the empathic response and become more aware of any tendency to sympathize is a focused attention on moving from what Whitworth, Kimsey-House, and Sandahl (2007) term “level 1 listening” to “level 2 listening.” A reflection practice immediately following a coaching session allows a coach to pay close attention to when the listening was focused on what the words meant to the client and what was happening in cases where the coach slipped into the level 1 listening (“what this means to me”). Mapping the cost of slipping into level 1 listening helps a coach strengthen their empathic stance.

Think of individuals you interact with most often on a daily basis. Perhaps it’s members of your team or a key person in your personal life. Jot down the names of two people you find a little challenging for one reason or another. Ask yourself the following questions (test the ladder of inference on each rung of the ladder):

Check yourself from the inside out, trying to notice whether any judgments, beliefs, and biases are coming from you and your story. Then take it a step further and spend the next several days consciously noticing how the change in your approach adjusts the way you view and understand others.

Reading on Empathic Stance

A coach needs access to a range of feelings that he is at ease exploring and expressing in his own life in order to provide ample room (a container, in a sense) for a wide range of feelings to emerge within the coaching engagement. The primary feelings of joy, anger, fear, and sadness cascade into more complex feelings of love, hate, betrayal, compassion, admiration, anxiety, and others. Most of us have stories about growing up in families where some feelings were more acceptable than others and, in some cases, in families where feelings were not allowed or where any feeling of any intensity was fair game.

The coach’s work in this area includes examining the repertoire of feelings that are in her comfort zone, the feelings that create uneasiness, and her favorite resting spot in the feeling domain. Harkening back to Horney’s model, our comfortable feeling range will dictate our capacity as coach and our inclination relative to the three-legged stool of moving toward, moving away, and moving against the client.

Start by paying close attention to your current repertoire of daily feelings by trying these two practices:

Readings on Range of Feelings

The work of family systems expert Murray Bowen (1978) examines the concepts of differentiation and triangulation within the framework of the family, but his work on differentiation is particularly relevant to coaches as well. Bowen views differentiation as the personality variable most essential to mature development wherein one is able to balance emotions and intellect (feeling and thinking) in conjunction with important relationships. This ability to make choices about one’s behavior in the moment by distinguishing between one’s thoughts and feelings builds a foundation for differentiating oneself from another.

For example, a well-differentiated coach who finds herself in a conversation with a client who is overcome with anger (or any other emotion, for that matter) will be able to manage her own feelings and reactions; she will speak calmly in the moment and proceed in a manner that is useful to the client. If the coach is not well differentiated, she may become overrun by her own emotions. Instead of being present for the client, she may move to fuse with the client by overcaring, moving the conversation to a safer topic, or easing tension by bringing up a third party (triangulating) and focusing emotions on that person. When the coach is less differentiated, she is more likely to mistake the client’s emotional responses as her own. Her decisions about how to proceed are then driven by a response to her own emotions instead of helping the client find healthy ways to work with their own.

These considerations make the concept of differentiation worthy of examination by the coach:

Bowen’s favorite assignment is a useful exercise for the coach: notice how often you triangulate, that is, engage in a conversation with one person about a third person:

Reading on Boundary Awareness

We are more than our thoughts and feelings—our head and heart. Our stories, ways of being, and habits are all housed in our body. The body tells a powerful story about each of us if we are alert to noticing these somatic awarenesses. Somatics expert Doug Silsbee (2008) writes, “We store in our tissues (our body) the default habits that form our identity” (p. 154). Strozzi-Heckler (2007), one of the early leaders in somatics work, writes, “Somatic practices allows a leader to literally feel and directly experience one’s own patterns of behavior and conditioned tendencies” (p. 33).

As always, a good coach needs to start by gaining a deep awareness of her own somatic story, learning experientially how her habits are stored in the body and how the sensations inside the body are a helpful tool as we seek to make changes in ourselves.

A number of considerations make the concept of somatic awareness worthy of examination by the coach. Silsbee (2008), for example, provides a useful map for a coach who wants to build his somatic literacy and offers four considerations:

Siegel (2001) highlights the importance of sensation in developing a heightened awareness of our feelings as well.

Reading on Somatic Awareness

Courage to challenge, that is, to share observations and provide feedback to the client, is a hallmark of great coaching. This capacity building begins on the inside. The work of challenging a client to see another view, examine areas that are uncomfortable to explore, or surface a pattern that is out of the client’s awareness requires courage combined with a strong working alliance. The working alliance communicates to the client, “We are working this territory together. I am committed to helping you get as close as possible to your goals.” This courage to challenge a client’s thinking, frame of reference in the world, or self-limiting story is an important part of our value as a coach.

The late Ed Nevis, an organizational development (OD) sage, often talked about two important approaches in creating new awareness with a client: evocative and provocative. The evocative approach is void of challenge and includes asking good questions that seek to heighten the client’s awareness around that which he can’t yet see. The provocative approach requires more courage and comes later, when the working alliance is well established. The provocative is more powerful and forceful in bringing something to the client’s awareness in the moment through the use of self in sharing observations, providing feedback, and challenging the client’s current thinking.

Tolbert and Hanafin (2006) developed the concept of the perceived weirdness index (Figure 4.5) in the OD field to underscore the reality that change takes place for most of us at the edges of what is familiar and what is different. The practitioner with an optimal PWI index is seen as different from the client, able to challenge the client, comfortable taking some risks in sharing observations and providing feedback to the client. In their model, the coach with a very low PWI would likely be focused on the support side without the courage to challenge. Over time this coach likely gets absorbed into the client’s system without much awareness that this is happening.

Sharing observations for which a client is often unaware also takes strength and courage for the coach. Observations as they pertain to the overall goals of the coaching work are essential to great coaching. There is often a tendency to shy away from this part of the coaching work in the early stages of becoming a coach, and for all the obvious reasons: it takes keen observational skills, a sense of timing, a thoughtful linking to the coaching goals, and some courage.

Several considerations make this work easier for a coach:

When these important considerations are in place and the coach continues to find it challenging to provide important observations, the work in deepening this capacity moves to further examination of the coach’s inner landscape. Self-inquiry might include exploring these questions:

Reading on Courage to Challenge