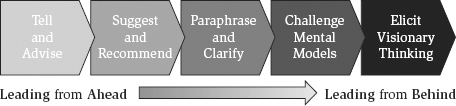

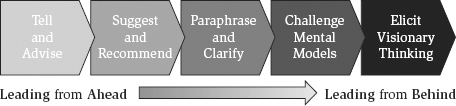

Figure 5.1 Leading from Behind

The work of self as coach is ongoing, and it serves as a necessary prerequisite to an essential stance in masterful coaching: leading from behind. In this chapter, we revisit the concept of leading from behind, developed at the Hudson Institute more than two decades ago, and examine it as a natural progression from deepening self to facilitating change in others.

A leading-from-behind stance is particularly important at specific stages in the coaching engagement. It’s a given that the coach is equipped with coaching knowledge and skills along with a coaching methodology and comes to the coaching engagement prepared to lead the way in the unfolding process. However, and most important, when it comes to articulating the change or adjustment the client is committed to making and facilitating the environment wherein the client can attain sustainable results, a leading-from-behind stance is what is called for. Robert Quinn (2004) aptly captures this dance between a step behind and out in front telling and fixing when he writes:

Telling is not effective in situations requiring significant behavior change because it is based on a narrow, cognitive view of human systems. It fails to incorporate values, attitudes and feelings. While people may understand why they should change, they are often not willing to make the painful changes that are necessary. When the target of change begins to resist, the change agent often becomes frustrated and turns to an even more directive strategy [p. 70].

Today most coaches have spent many years in the role of leader themselves and the general strategy Quinn references of telling is a well-worn habit. Yet in the role of coach, when we are in the heart of the change work in the engagement, the coaching approach must move away from telling and solving problems toward facilitating deep transformative change.

We coined the phrase leading from behind as one of the hallmarks of a great coach in order to create a compelling image of the coach’s ability to walk slightly behind the client, supporting, challenging, and coaching him or her to facilitate a sustainable and transformative change that tracks to the client goals and acknowledges the multiple layers of systems (team, organization, company) at work. We crafted this provocative phrase in our earliest years of coaching to emphasize a coaching stance that promotes deep and lasting change, understanding that the shelf life of even the soundest of advice is extremely short.

This phrase has surfaced in recent years relative to the role of a leader, and there it’s used a bit differently. Nelson Mandela (1994) considers leading from behind to be his style of leadership. For him it means intentionally harnessing the genius of others without abrogating his strength as a leader. It’s probably important to acknowledge as well that the phrase has been thoroughly politicized in recent and highly polarized times in the United States as denoting a lack of strength and leadership, quite different from our interpretation and use of the term relative to coaching.

Consider this situation in illustrating a leading-from-behind mind-set. A client wants to be more concise and clearer in his communication style. It would be easy enough for the coach to simply tell the client what to change in order to accomplish this. It might even work, at least over the short term. However, a more lasting and sustainable approach requires leading from behind to jointly surface what the obstacles are to making this change, what the current awareness level is to present behaviors, the benefits that will make this big adjustment in behavior worthwhile, and the competing priorities that might surface along the pathway to change. This is not a passive stance for the coach: it requires strength and courage to challenge at the right times, provide feedback, and share observations that are not self-evident to the client. It also requires the strength of the coach in holding the client accountable for the changes he has committed to making.

The coaching concern may be a shift in one’s leadership style, a new way of managing tough conversations, or a pivotal decision. Whatever it is, the stance of leading from behind reminds the coach that our work is in empowering the client to come to terms with the challenges that he or she needs to address in order to fully commit to taking a new step forward in work and life.

For most of us as leaders and professionals, this artful approach of leading from behind initially seems counterintuitive, inefficient, and at times impractical. We ask ourselves: Why not share my wisdom with my client? Why not impart my expertise in order to help the client avert a poor choice? No one would disagree that an efficient short-term solution often emerges from an advisory or consulting approach. However, longer-lasting changes are thwarted when the coach moves ahead of the client and suggests his or her preferred approach or builds the client’s solutions for the challenge at hand. This is the essence of the shift from leading the client to the solution to stepping back and leading from behind. The subtle art of restraining the self in order to lead from behind is one that can be cultivated only once the coach has engaged in the practice of deepening the self as outlined in Chapter Four.

Alan Fogel’s (2009) work on the psychophysiology of self-awareness provides a deeper view into the leading-from-behind approach that also connects the inner and outer manifestations of self. He describes a process he terms “coregulation” wherein two individuals dynamically coordinate their actions by sensing boundaries between self and other. He uses a powerful example of helping an infant learn to sit up. The adult take the hands of infant as she lies on her back and pulls gently and firmly enough to sense and feel the infant’s muscles begin to engage. The adult is leading from behind in order to facilitate the infant’s growth and development. If instead the adult fails to consciously engage in Fogel’s concept of coregulation, he will pull too quickly or use too much force. The infant may now be sitting up, but the adult has done it for the infant and the young one has been robbed of the opportunity to build muscle and capacity to sit up on her own.

A leading-from-behind stance is in no way implicit permission for the coach to take a position of primarily a supporter and encourager. The coach must continually coregulate and find those moments and opportunities to pull and challenge just enough to promote real growth. The lead in leading from behind serves to remind us that the coach leads the process by employing a sound methodology. The coach sets the stage to gain clarity and focus in the engagement, and the resulting aspirational goal and behavioral goals to support this are owned by the client. Leading also requires that the coach deftly determine the motivation and commitment of the client, and when the work begins, the coach knows when to challenge, when to share critical observations, and when to confront important areas of discovery with the client. The coach is always leading, but just a step behind the client or at times right alongside, when change is on the plate.

Leading from behind requires restraint and self-management at just the right times while we actively lead the process of coaching. This is a masterful practice that requires emotional agility, deep personal awareness, and the ability to harness the urge to move out ahead of our client. The stance necessitates powerful listening and questioning abilities and a portfolio of coaching tools and techniques that can be easily accessed when the time is right and they fit the needs of the client. The simple model in Figure 5.1 captures the positions that support either the leading-from-behind stance or the out-in-front approach. Masterful coaches will want to move toward the right, in the direction of leading from behind, particularly when the coaching is focused on facilitating an important change in the client’s behavior.

Figure 5.1 Leading from Behind

Leading from ahead is what we do when we are in the telling-and-fixing mode. The client arrives at our door with an issue, and before we’ve taken the time to grapple with the current situation, construct the vision for our work together, the coach believes he sees the client issue clearly and has a strong sense of the next action steps that will be important for the client in order to fix and solve the current dilemma. These are the ways to recognize when you are using a leading-from-ahead stance:

Table 5.1 provides some brief vignettes and contrasting approaches.

Table 5.1 Examples of Leading from Ahead Versus Leading from Behind

| Client Situation | Leading from Ahead | Leading from Behind |

| “I’ve got to get my team behind this initiative now.” | “I’ve got a couple of ideas on how you could do that.” | “So what are you doing now that’s not working? Any ideas about shifts you could make?” |

| “I need to find a job now!” | “Okay. Let’s put together a list of possibilities that you can start working on this week.” | “Okay. I’m thinking it will be useful to look at what’s going to be important for you to attend to in order to get a job. Agree?” |

| “I wish I weren’t such a perfectionist; it makes meeting deadlines so darn hard.” | “Jack, you’ve mentioned this before, and I want to recommend a great book that really gets to the heart of perfectionism. Also I have some steps you can start taking now to see if you can curb this.” | “Jack, you know when you mention this, it seems like an important part of your goal to meet deadlines, so I’m guessing we ought to take a closer look and see what we can learn about how this gets in your way, when it shows up most, and so on. Can you give me an example or two of this over the past couple of weeks?” |

| “I really blew up today. I’ve had it with one of my team members, always making excuses, making light of deadlines. The guy is a jerk.” | “I understand that one, and making excuses won’t get you any closer to meeting deadlines. I’m thinking it could be helpful to implement a weekly plan with this fellow and hold him more accountable to time lines. You agree?” | “Boy, that sounds hard. I’m also struck by how closely it links to your goal of developing stronger relationships with those on your team. I’m thinking it will be smart for us to step back and take a look at this situation and see what there is to learn about yourself. Agree?” |

| “I’m sorry I’m late for our appointment today. I just had so many deadlines . . .” | “Jack. No worries. I know you’ve got a busy schedule. I might have planned my day a little differently if I knew you were running late, but it’s really not a problem.” | “Jack, I appreciate your acknowledging that, and I want to explore this a bit with you. You are wanting to be viewed as more reliable and dependable by your team—so I know making commitments matters to you—and at the same time, I can’t help noticing that you have cancelled two recent appointments at the very last minute and you are a half-hour late today and no call. What do you make of this?” |

In each of the examples in Table 5.1, the coach with the leading-from-ahead stance hijacks the client’s sense of responsibility for his actions and next steps and misses important opportunities to allow the client to step back and observe self. The coach who embodies the leading-from-behind approach is clear about who needs to be committed to the changes in the behavior and understands how to facilitate deeper awareness and sustainable change through challenging, sharing observations and reflections, and holding the client accountable. Table 5.2 is a descriptive view of these two contrasting approaches.

Table 5.2 Features of Getting Ahead Versus Leading from Behind

| Getting Ahead of Your Client | Leading from Behind |

| Telling | Asking |

| Consulting approach | Change agent approach |

| Sitting in a knowing place | Holding a curious mind |

| Increased control | Reduced control |

| Knowing | Wondering |

| Changing a specific behavior | Inviting insight into behavior |

| Fixing the problem | Exploring together |

| Seeing a problem to be fixed | Seeing an opportunity |

| Imparting your wisdom | Practicing transparency |

| Hierarchical | Participatory |

| Prescriptive | Inquiring |

| “How would you like to fix this?” | “How do you see it?” |

| “What are the solutions?” | “What are the opportunities?” |

| Moving directly from problem to solution | “What will the obstacles be?” |

| Level 1 listening | Levels 2 and 3 listening |

| Transactional | Transformative |

Underlying the leading-from-behind stance is an understanding of the key elements that create the possibility for sustainable change in our clients. Masterful coaches need significant knowledge about how to support change in clients. The body of literature informing this question is considerable, and a brief look at some highlights that link to and support a leading-from-behind posture in coaching are included below. An in-depth review is in Part Three.

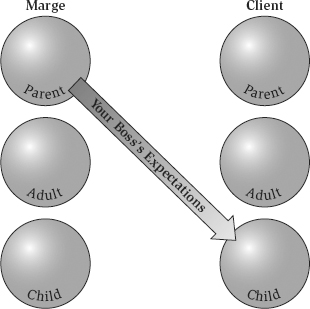

Transactional analysis (TA), developed by Eric Berne (1964), highlights his model of the three ego states of parent-adult-child that exist internally and externally for each of us. It’s a simple, practical model that readily maps to the dynamics of leading from behind versus leading from ahead.

In TA language, each of us has internalized three ego states: parent, adult, and child. The parent state has two parts, the nurturing parent and the critical parent, an amalgamation of our collective parent. The adult state is the center of logic, reason, and decision making. The child state is the center of feelings, and it includes both a “free child” and an “adaptive child.”

When the coach assumes the advice-giving stance, it’s likely that a parent-child dynamic gets engaged, and the client finds himself in the role of child accepting the advice of the coach (as parent). The TA model alerts a coach to the dynamic that unfolds when we take on the leading-from-ahead stance of, “I know,” “I’ve got a plan for you,” or “Listen to my great advice.” Consider this coaching situation. Marge’s client comes to the coaching session today feeling pretty ticked off at her boss. She tells Marge, “My boss is really out of line this time. He expects too much of me. I’ve worked late for the past seven nights, and now at the last minute, with no warning, he drops a big project on my desk that will ruin my plans for a weekend getaway I’ve planned.” If Marge responds, “Boy that’s unfortunate, but remember that you are still early on in your new role and your boss expects you to pay your dues and prove yourself. What can you do to make this work for you and perhaps postpone the weekend getaway plans?” In TA parlance, Marge has assumed the parent position and the leading-from-ahead stance, while an unaware or off-guard client can easily assume the child position (Figure 5.2), with the result that little important change ensues.

Figure 5.2 Transactional Analysis in Coaching: Eliciting the Child Ego State

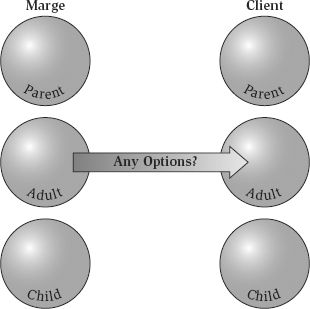

In short, the TA framework is an easy way to map what our inquiries and observations as a coach will likely elicit in our client. Typically when we get out in front of the client and push our agenda and solutions, we’ll pull on the client’s child state. If, on the other hand (as in Figure 5.3), you share observations and make inquiries from a position of curiosity, it will be much easier for the client to consider new possibilities.

Figure 5.3 Transactional Analysis in Coaching: A Better Path

While a parent-to-child interaction may lead to a brief change in behavior, it is seldom going to provoke lasting change for the client. The parent-to-child dynamic aligns with a leading-from-ahead approach, whereas an adult-to-adult interaction links to the leading-from-behind stance and factors in the reality that in order to create sustainable change, the client needs to be committed to the change and responsible for taking the action of what is required to achieve deep change: the all-important client ownership that breeds lasting change.

Kurt Lewin’s field theory is relevant to coaching because he emphasizes the need to expose and understand the forces at play that support or undermine a change an individual (or system) wants to make. In providing this perspective, Lewin (1997) underlines how challenging even the most desired changes are for us. His step-by-step process emphasizes the need to investigate the client’s commitment to a change and then examine the many obstacles that might emerge as the client seeks to move forward with this change. His work aligns well with the leading-from-behind stance and reminds the coach that it’s impossible to facilitate deep and lasting change by using the fix-and-tell approach.

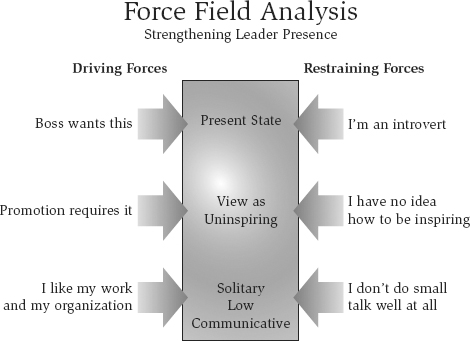

Consider Lewin’s model in the following coaching situation. Mary’s organization routinely provides coaching to its more senior leaders, and Mary’s boss has recommended coaching for her in order to strengthen her leadership style. In particular, her boss views Mary as needing to strengthen her communication style with her team and ramp up her ability to inspire and motivate the team. In a leading-from-ahead approach, a coach might leap to the rescue and offer Mary some tools and reading resources that could be helpful. Lewin’s force field analysis reminds the coach instead of the importance of uncovering of obstacles rather than seeking solutions at this early stage. Some of the restraining forces and driving forces are uncovered with Mary in Figure 5.4, and this becomes an important part of the exploration in the early stages of the coaching engagement.

Figure 5.4 Lewin’s Force Field and the Example of Mary

The TA model underlines the need for a dialogic exchange (adult-to-adult), and Lewin’s model highlights the importance of slowly uncovering the competing priorities and natural obstacles that arise whenever a coach is working with a client to make changes in long-held habits and approaches.

There are several key change models that provide powerful confirmation that real change happens when a coach can lead the client to a state of self-revelation that occurs from the inside out. Part Three offers an in-depth review of theories and concepts in this arena.

In Part Four, we examine the stages of the Hudson coaching methodology and look at how some elements of those stages require leading-from-behind strategies. We learn that coaching requires a sound methodology that tracks the process from beginning to end and provides an overall structure that links the contract for change (the aspirational goal and the behaviors goals linked to this) to the work that occurs throughout the engagement and the outcomes that occur as a result of those goals.

The Leading-from-Behind Mind-Set in a Nutshell

Part Four examines in more detail the intersection between elements of a sound coaching methodology and this leading-from-behind stance.

For now, the following case example illustrates the pitfalls of moving into the fix-and-tell stance of leading from ahead.

This brief snapshot into a coaching session with John is illustrative of the most fundamental challenge the coaching approach metes out to a coach. The coach wants to add immediate value to his client. He gets out in front of John and moves to action building relying on his knowledge and past experience far more than thoroughly understanding the client’s situation and needs.

Yet what we know about how people create sustainable pathways to change runs counter to the fix-and-tell approach. Leading from behind emphasizes a philosophy and an approach to facilitating change in our work with others. It is the artful practice of walking slightly behind the client as she uncovers the obstacles that make her stated goals difficult for her to achieve, while simultaneously leading the coaching process by challenging, observing, providing feedback, and supporting the client as she wrestles down the obstacles and collaboratively builds practices and actions that begin to help her cross the bridge to a new way of being.