© The Hudson Institute of Santa Barbara

© The Hudson Institute of Santa Barbara

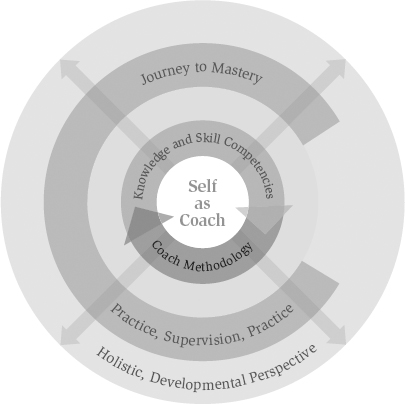

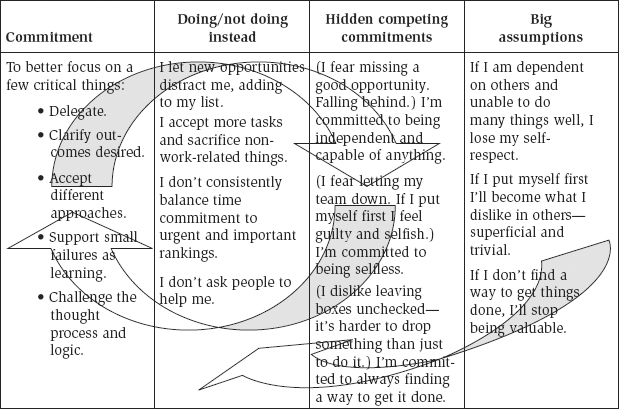

Several fields of study and research are foundational to this important domain of coaching: the working alliance, change theory, systems thinking, outcome measures, and ethics. This chapter reviews important highlights in these five baseline areas in support of a sound coaching methodology.

At first glance, a thorough methodology for the coaching engagement can appear overly structured, linear, and formulaic, but a methodology is simply the scaffolding that supports the coach’s work rather than dictating a step-by-step process. While it appears on the surface to be linear, it never is, and a useful methodology ought to always be adaptable, fluid, and flexible enough to accommodate each coaching engagement. Underlying the scaffolding of the methodology is the all-important relationship between the coach and the client—the working alliance. This is a respectful, trusting, safe, and open relationship that a coach builds with the client and creates the foundation for the truly transformative work to occur. Without a working alliance, a methodology is sorely insufficient in facilitating a client’s development.

The field of psychology provides valuable research underlining the pivotal nature of this relationship in the therapeutic domain. Researchers in psychology have engaged in extensive studies to determine just what the key ingredients are in a successful therapeutic engagement, and each successive research finding points to one pivotal element: the working alliance between client and therapist. According to Bordin (1979) and Wolfe and Goldfried (1988), this working alliance (the collaborative bond between therapist and patient) affects the therapeutic outcome far more than any specific therapeutic approach that the psychotherapist takes. Whether the approach is behavioral, analytical, psychodynamic, or eclectic, it is the quality of the working alliance, and not the approach, that leads to successful outcomes. Although the field of coaching has not yet researched this dynamic thoroughly, it’s quite likely we can extrapolate from the extensive research in psychotherapy and infer that similar dynamics are at play in the coaching engagement.

De Haan (2008) works to extend this research into the coaching domain and defines the working alliance in the coaching relationship as “1) the coachee’s experience of the coach being supportive and empathic; and 2) a sense of working together towards the goals of the coaching.” (p. 132). Building a working alliance with a client requires all of the elements already outlined in the self-as-coach model. The quality of the alliance is dependent on the coach’s mastery of self: the ability to empathize, be present, be comfortable within a wide range of feelings, and to challenge while remaining aligned around the coaching goals and to support at the right times.

At each step in the methodology, the working alliance is at the center of the work, whether it is talking through information obtained through stakeholder interviews, exploring the client’s level of commitment to making a change, or examining the obstacles that arise on the path to a new way of being.

In our work training coaches, we require each new coach to receive several months of coaching with an experienced coach over the course of the learning program. We ask the coach in training to interview at least two coaches to determine which might be the best fit given his or her particular needs. Once the trainees have completed their coaching, we ask how they chose their coach, and in each situation, assuming competence and experience are prerequisites, it is the nature of the connection that occurs in that first conversation that lays the ground for the engagement. Good coaches have honed the self-as-coach terrain in order to become fully aware of how they are perceived, how they connect, and what barriers might exist that will make it difficult for clients to feel at ease. Humility, compassion, empathy, access to feelings, humanness, respect, and authenticity: a lofty goal for a great coach to realize.

Change is at the heart of coaching, and deep change is what a thorough coaching methodology seeks to support. How does a coach help a client become a slightly better version of his or her current self? How does a coach work with a client to make a change that he or she can barely grasp, while others around this person see it so clearly? Perhaps it’s an abrupt style, a discounting approach, a diminutive presence, an unapproachable veneer. How does a coach understand change in his own life—those areas that have been on the list to change for some time and yet nothing happens? Understanding the elements that must be present to ensure change is essential for coaches lest we veer toward problem solving and consulting for the client.

There exists a series of well-researched models for supporting change that are particularly useful for the coach, including the work of Kurt Lewin, Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey, Richard Boyatzis, and Rick Mauer. The work of these theorists and practitioners is reflected in the coaching methodology articulated in Part Four, from framing the aspirational goal, to gaining feedback from key parties in the system, to examining the level of commitment and explicitly uncovering the obstacles to change. Each of these steps in the underlying coach methodology is in support of mapping the way to a meaningful and sustainable change in the client’s life. What follows is a brief review of these theorists.

Kurt Lewin, a pioneer in group and organizational psychology, developed a three-stage change model in the 1950s (unfreeze-change-refreeze) in an early attempt to provide a change process that included a series of progressive steps instead of a sense that change is a random, uncontrollable event (Figure 8.1):

Lewin’s (1997) work provides an important early foundation for understanding the elements in facilitating change. Although his model was focused on organizational change, he highlighted the importance of examining the level of commitment to change and emphasizes the need for clear motivation on the client’s part in order for change to occur.

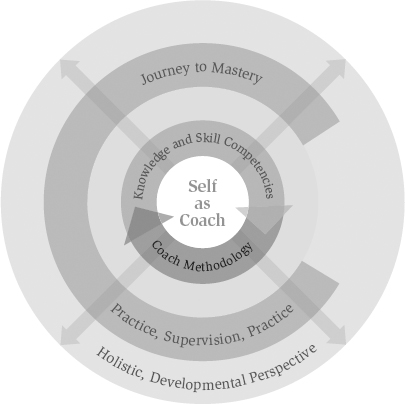

Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey’s (2009) recent work on immunity to change affirms Lewin’s findings and further uncovers the powerful system of immunity embedded in each of us when change is under consideration (Figure 8.2). Their studies suggest that three ingredients are needed in order to facilitate sustainable change:

Figure 8.2 Kegan and Lahey’s Model of Change

Both Lewin’s and Kegan and Lahey’s research places the spotlight on the importance of gaining the client’s commitment to do the work of coaching and taking the time to carefully assess the level of motivation, the urgency of this change, the competing priorities, and underlying beliefs that hinder the path to change and the willingness to do the hard work required by the change. Change may sound sensible and reasonable to both the coach and the client, but without a deep sense of commitment and a clear sense that one’s old survival strategies are no longer effective, the work of coaching will fall short of the goals.

Richard Boyatzis (2011; Boyatzis, Goleman, and McKee, 2002; Boyatzis and McKee, 2005) widens the lens in understanding how change happens and places the spotlight on the ideal self as the most important driver in creating a sustainable change. His step-by-step change model (Figure 8.3) begins with a focus on identifying the ideal self and then moves through the cycle as follows:

The power of an aspirational goal rooted in the heart and mind of the client is essential in order to create sustainable change. Too often coaches develop a coaching agreement tied to a to-do list or a series of behaviors that need improvement. Boyatzis’s research confirms the importance of an aspirational goal that resonates at an emotional and cognitive level for the client and inspires him or her with the hope of a slightly better version of self through the coaching work.

Finally, Maurer’s (2010) contributions highlighting the power of resistance are essential in examining how a coach facilitates change over the course of the entire coaching engagement. He highlights the reality that resistance, a force that slows or stops movement, is a natural, predictable part of any change and a change agent needs to understand this in order to work effectively with this resistance. He outlines three levels of resistance:

Maurer’s work confirms the importance of a clear, visceral aspirational goal that provides hope and inspiration to the client, capturing both the head and the heart. It also underlines the importance of uncovering the natural obstacles that will surface anytime change is afoot. Exposing the obstacles and inevitable resistance helps coach and client build an action plan that includes important practices that build the platform for sustainable change to occur.

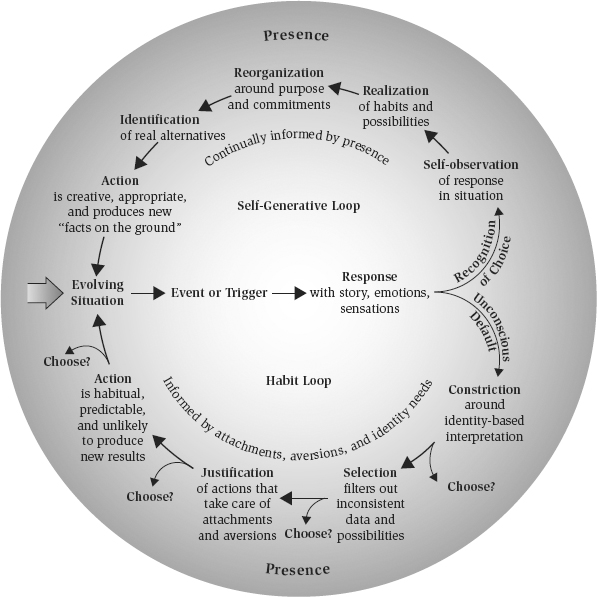

Doug Silsbee’s book Presence-Based Coaching (2008) includes a chapter focused on how humans change in which he explores what is required for a coaching client to become self-generative by moving from automatic to self-generated behaviors, habits, and choices—and change long-held habits and behaviors. The progression of practices he describes provides a helpful framework in supporting the work of building the coaching plan with a client:

Silsbee’s model (Figure 8.4) portrays the pathway of ingrained habit and the self-generative loop that leads to opportunities for new choices.

Figure 8.4 Silsbee’s Self-Generative Loop

Source: Silsbee, D. (2008). Presence-based coaching: Cultivating self-generative leaders through mind, body, and heart. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

The link between his work and the latest work in neuroscience articulated by Siegel (2010) lies in the finding that a change in behavior requires enormous focus of attention and mindfulness on the part of the client. This process of becoming mindful and focusing attention on self-observation takes time and is more strenuous than we’ve previously believed. Building practices to support this ability to self-generate new habits and behaviors is essential.

Silsbee’s work in mapping self-generative practices informs the heart of building a coaching plan with a client. In essence, we are working with clients to change habits and behaviors that will allow them to get as close as possible to the goals that matter to them. Robust, thorough practices that support this change and help the client understand the complexities of change are essential to the success of a coaching engagement.

Systems thinking provides an invaluable perspective into the complexities of facilitating change throughout the coaching engagement, from the moment you receive a phone call from someone seeking your services until the engagement has fully concluded. Whether you are working with a leader inside a global organization or an individual in a transition outside the organization, an integrative systems perspective is essential for a coach. Systems are at play everywhere, whether we are managing our own complex internal systems, the systems present in any coaching relationship, or the larger context of the client—the team, the organization, and the culture. Organizations can best be understood through the lens of systems thinking, and many of the central elements of family therapy help us understand the systems dynamics of coaching in a business setting.

The work of Murray Bowen (1978) in family systems theory, as well as the systems thinking of Peter Senge (2006) and others in the field of organizational development, provides a useful foundation. A coach might be tempted to take it at face value when a client reports that her teammates are impossible to get along with. But when we have examined the entire system (this might be uncovered in stakeholder interviews and observation in action), we quickly find that team members have a different perspective. Some team members might find the client to be so rigid that they prefer to work around her; others might say that their approach is to simply ignore her whenever possible. A system’s perspective teaches the coach that allocating blame is irrelevant; instead, the goal is to determine which interactions inside the system need to change and how to accomplish that change in order to make it more satisfying for everyone and help the client get closer to the bigger goal he or she has set.

A handful of systems thinking concepts are particularly relevant in coaching, including the ones we examine next: homeostasis, triangulation, family roles, and interactional force field.

Organisms and human beings strive to maintain things just as they are. Whether we are happy about our situation or deeply distressed, our tendency is to remain attached to what we know instead of risking a change that plunges us into the unknown. This is why dysfunctional marriages last so long and why toxic corporate cultures are slow to change: we are more comfortable with what we know than we are with risking change. This concept is particularly important for a coach to grasp relative to how change occurs. To understand the power of homeostasis is to comprehend the profound work involved in helping a coachee make changes she asserts she wants to make.

Early in practice, a coach will often experience frustration with a client who seeks coaching in order to adjust a specific and long-standing behavior—say, a tendency to talk over people and generally talk too much and listen too little. The client seems motivated, her boss believes this is an important area of growth, and the client’s team would likely benefit significantly by this change. So when the client repeatedly returns to the coaching sessions reporting no progress but “new fires” to put out, a coach ought not to be surprised. This is homeostasis at work, and it underlines the need for a coach to challenge at the right times, transparently share the observation that the reason the client came to coaching is continually eclipsed by the fire of the week, and spur the client to notice this so that together the coach and client can reflect on what’s at play.

The concept of triangulation developed by family therapist Murray Bowen (1978) is of particular relevance in the work of coaching. Bowen found that when tensions rise between two individuals, the most common way to diffuse the stress and tension is to involve a third party. In fact, when Bowen was teaching medical students at the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas, he would give his medical students an assignment before leaving for the December holidays. He would ask them to notice how often over the family holiday they would observe one member of their family talking to another about a third member of the family in an effort to reduce stress and avoid more personal and direct conversations. Much like Bowen, Mary Beth O’Neill (2007) views triangulation as a mostly unconscious effort to reduce one’s stress that typically results in protracting a difficult situation. We all find ourselves in these situations on a regular basis: Jane is upset with the way a member of her team managed a project and, what’s more, Jane’s boss is now unhappy with Jane about it. Instead of talking directly with her team member, Jane goes to a coworker, or two or three, and vents.

A coach often experiences this dynamic during the coaching session as the client talks to the coach about a third party (not present) instead of talking about herself. As the coach redirects the conversation and focuses solely on the client, the sense of immediacy and the appearance of emotion often surface because the conversation becomes more meaningful, and also riskier, for the client. It’s far easier for the client to talk about another person and his or her faults and flaws than to consider what he or she can do and change about a particular interaction or situation. Triangulation can also happen very early in coaching when a coach is contacted to provide coaching for a person referred to as a “difficult leader,” only to find out that the leader’s boss finds this person difficult but never provides candid feedback to the individual. Hence, as the tension continues to rise for the boss, he calls in a third party to do what he has not done.

Family therapy literature provides several views on the common roles played in families and carried into adult life at work and at home. Virginia Satir (1988) outlined five commonly played family roles, each with a particular communication style:

For Satir, the focus is on noticing patterns of behavior and stances in the world that show up at work and in one’s adult life that are remnants of old family roles.

It’s essential for coaches to understand the roles they are drawn to and the price and benefits of these roles. If a coach is prone to what Satir terms the placater role, this will have important implications for the coach and require a conscious effort to build more confidence and strength in order to meet the client’s need for candid feedback, challenging, sharing observations, and continually focusing the work. An understanding of family roles will also prove useful to the coach when working with the client.

Mary Beth O’Neill (2007) uses this term to describe the power of the web of relationships (systems) at play, whether it is two, fifteen, or one hundred people. O’Neill reminds coaches that it is critical to “recognize how organizational systems affect you, including the ones you are in and the ones you co-create and it’s equally important to attend to the system co-created between you and your client” (p. 52).

Every system develops a dance, and inside the coach-client relationship, it’s vitally important to recognize this as the coach. In each coaching engagement, the coach is inevitably drawn into the client’s repetitive patterns, and to the extent that the coach is able to discern these patterns, it is enormously valuable in the coaching work. The coach who can observe a client’s pattern and artfully work to share this with the client creates a powerful in-the-moment shift that combines emotions and thoughts and paves the way for heightened awareness and change. Here is a series of examples. In the first set of examples, the coach inadvertently steps into the client’s system without noticing and misses opportunities to address the client’s actions and stories:

In this next series, notice how the coach uses the opportunity (and engages his self-as-coach awareness) to help the client access a blind spot or important part of his or her story that might be connected to important elements of the coaching contract:

Systems thinking is foundational to the coaching methodology because it is present in every step of the coaching process. It begins when the first conversation is opened and as the external coach seeks to understand the needs of the organization, the roles of the boss, the human resource partner, and potential clients. It exists when crafting the aspirational and working goals with the client because these are aligned with the larger system, it shows up at an internal level when examining the natural resistance and obstacles to change, and it surfaces when we consider throughout the work how the effectiveness and the impact of the coaching will be evaluated. This requires coaches to manage their own internal system and observe the systems dance at play in each coaching session.

Outcomes and the measure of the impact and results of effective coaching are essential, and the work that ensures the ability to do this well begins when the first conversations occur with the client or the sponsor engaging a coach in the engagement. They then continue through careful, thorough contracting that focuses on adjustments and changes that the client is committed to and, when internal, that the organization is aligned with.

Jack Phillips (1996) developed a return-on-investment methodology that provides accountability through a measurement focus (Figure 8.5).

Ethical considerations are easy to overlook early in coaching, but it becomes obvious that ethics are at play everywhere in coaching. A short list of ethical issues might include

The following sources on ethics are useful: