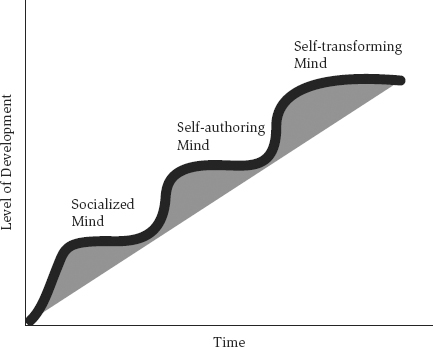

Figure 12.1 Kegan and Lahey’s Levels of Development

Source: Kegan (1982).

A well-rounded coach operates at multiple layers and needs more than theory and skill-based competencies, a coaching methodology, an ability to use self as coach, and a tool kit. A great coach needs to be grounded in the broader context of the human being in today’s world. A holistic and developmental perspective transcends any singular coachable issue or pressing challenge in the life of the client and provides a deeper context for the client embedded in the complex layers and systems of life. This more expansive lens allows a coach to thread singular issues into the broader themes of the client’s life and articulate aspirational goals that resonate with both the challenges of the day and the broader complexities of life.

When we talk about a developmental perspective, there are two distinct and important realms for our consideration. The first is found in the concepts of constructivism (the notion that as individuals we construct our own reality) and the second in developmentalism (the notion that as individuals, we evolve through time as we weave through transition and change in our lives). The origins of constructivism emerged in the early work of object relations (relationship of self to other) theorists, including Donald Winnicott (1990) and Otto Kernberg (1995). Kegan’s (1982) work linked Jean Piaget’s cognitive development framework to the field of object relations, thereby providing a foundation for our understanding of the stages of development in our self-other constructions or our ability to make meaning out of any given situation in our lives.

Kegan’s contributions are particularly germane to the work of coaching, because he draws attention to the shifts in how adults make meaning of their world over the course of their lives. His original work outlines five levels of development in the adult’s life, representing new levels of consciousness as the individual moves through each stage, growing in complexity and allowing the adult to wrestle with more complex understandings and situations.

Kegan and Lahey’s recent book, Immunity to Change (2009), condenses these stages into three broad levels of development. The first is the socialized mind, characterized by individuals who want to live within a set of rules in their life and in their work. Their decisions about how to behave in the world are shaped by what they believe other people in authority roles expect of them in their role. They live their lives according to a specific set of rules handed down to them by a person or institution in a position of authority. People at this stage of development make excellent team members because they adhere to the rules and remain extremely loyal. According to Kegan and Lahey, about 20 percent of the adult population is at this stage or striving for this phase.

Jamie is an example of this level. He has just completed his law degree, and he’s eager to take his first step into the legal profession and launch his career. His parents are particularly proud of him because he’s followed in the footsteps of his father and his grandfather, and he’s now about to join his father’s firm. Jamie readily admits there is a sense of pressure around getting it right and wanting to secure his family’s approval at this important juncture, and he also confesses that there is comfort in having a clear pathway to the future that others have helped him create at this stage in life.

The second level, the self-authoring mind, is characterized by individuals who set their own goals and work hard to achieve what they’ve targeted for themselves. They are clear about their own internal set of values and guided by their own compass rather than an external set of rules. They are comfortable taking a stand that might be different from those of others around them. They are very focused and driven by their own goals and work hard to get others to adopt the same agenda. According to Kegan and Lahey, about 75 percent of the adult population is at this stage or striving for this phase.

Barbara, age fifty-two, with a solid record of work success behind her, is an example. She has taken some traditional paths over the past three decades and now is ready to step off the safe road and try something quite new and different. Some of her friends and family think she is crazy to bid farewell to a corporate career that is secure and prestigious, but Barbara is ready. She is clear about her sense of purpose at this stage in her life, and she’s ready for a bold challenge.

The self-transforming mind is the third level, characterized by individuals who are clear about their own inner set of values and simultaneously able to step back and explore other perspectives and consider the limitations of their own values and goals. They are willing to freely invite feedback, contemplate other points of view, and generally explore the complexities and contradictions of life’s issues and dilemmas.

According to Kegan and Lahey (2009), few of us reach this level of development, so perhaps we can see this evolved state of being best in an iconic figure such as Nelson Mandela. Mandela is a powerful example of a human being with clarity of vision forged under the most trying of times and a continual ability to step back and view perspectives differing radically from his own.

Individuals, write Kegan and Lahey (2009), are able to move to higher levels of development as they become able to consider broader perspectives about themselves and others (as shown in Figure 12.1). As long as the individual is trapped in viewing his or her own experience as “the real experience,” this person’s capacity to fully operate in the world is limited.

Kegan and Lahey’s (2009) work becomes more complex and doubly relevant to coaches when we consider the combination of coach and client wherein the client is operating at one level while the coach is potentially operating at another. It’s easy to see that if a coach operates at the level of the socialized mind, it will be almost impossible to provide useful coaching to a client who is operating at the level of the self-authoring mind or beyond.

Otto Laske (2006b) applies Kegan and Lahey’s (2009) work specifically to the field of coaching and asserts that a coach cannot successfully coach an individual who is at a higher level of development than his or her own. Our way of making meaning within each stage is so engrained that it’s impossible to consider that there might be a different, higher state view. Laske has developed an instrument to measure one’s individual level of development and believes it could be useful in training coaches to examine the individual level of the coach in training.

This deeper meaning-making level of development in our social maturity is one important aspect of development that is woven into a broader examination of the whole person and the unfolding development that occurs over time and through periods of transition and change throughout our adult years.

At Hudson, we’ve developed a series of lenses into each of the important elements of understanding a whole person in a framework that captures our meaning-making capacities and examines a holistic and developmental perspective.