Mastery is an arduous journey for any coach. It requires conscious attention to the cultivation of self; demands continual learning about useful and relevant theories, concepts, and tools; and necessitates regular and consistent practice in the art and science of coaching. For each of us as coaches and for the field of coaching, this is our challenge and our goal: the ongoing quest for mastery.

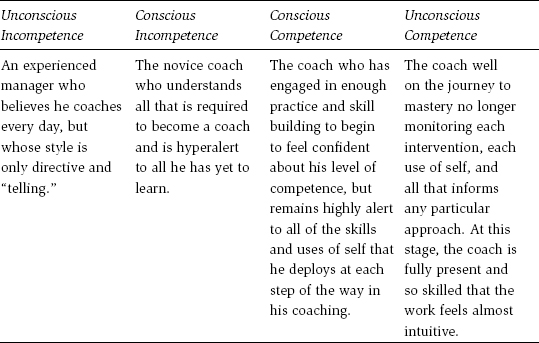

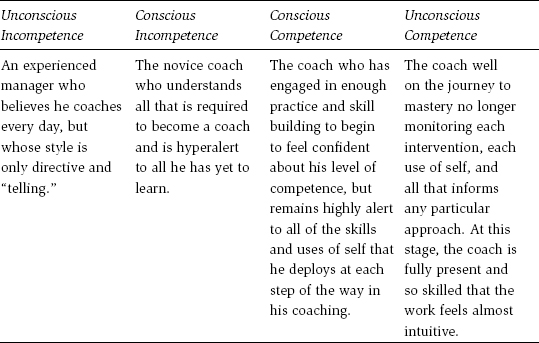

Howell (1982) provides a launching point for understanding the journey to mastery in his well-known model mapping the journey from unconscious incompetence to conscious competence. In his study of the progression from novice to master, Howell identifies four stages:

Because many professionals become interested in adding a coaching approach and skill set to their practice when they have already achieved significant milestones as leaders, Howell’s model is particularly useful in helping to frame a new learning journey (see Table 21.1). Many experienced leaders sense that coaching will be a very useful skill set to add, and many, in fact, believe they are already acting as coaches. However, within a short time of their examining the skill- and theory-based competencies and watching masterful coaching at work, their transition from the unconscious incompetent to the conscious incompetent occurs. The journey through conscious competence is a long one. It requires far more than a year of coach training or hundreds of hours of solo coaching in order to accelerate one’s skills on the path to unconscious competence. Continual development, reflection in action, and supervision experiences accelerate the progression.

Table 21.1 Coaching Examples of Howell’s Model

The path to mastery is not for the faint-hearted. The Dreyfus brothers (1980), Hubert and Stuart, researched the stages of the journey to mastery with a goal of understanding how to best support a student’s development. They distilled the stages of skill acquisition in complex learning in a study conducted for the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research. Their model and findings were subsequently and successfully applied to the process involved in learning a foreign language, chess playing, and flight instruction.

Today the Dreyfus model is widely used as a means of supporting the development of skills in education, medicine, nursing, and a variety of other professions, most recently in the study of the acquisition of coaching skills. Dreyfus and Dreyfus proposed five stages of development with specific definitions for each:

Catherine Robinson-Walker (1999) overlaid the Dreyfus model on the progression of a coach’s skills in Figure 21.1. Several of her interpretations are valuable for the developing coach, addressing several areas, including these:

Robinson-Walker’s work overlaying coaching on the Dreyfus pathway from novice to expert also links the stages with Howell’s model in a helpful and integrative manner. Bennett and Rogers (2011) take this a step further in their study with twenty-six coaches representing four categories of coaches: beginner, skilled, practiced, and seasoned. They conducted semistructured interviews comparing advanced beginners with experts in order to test the applicability of the Dreyfus model in coaching. They found distinguishable differences between advanced beginner coaches and expert coaches, thus validating the Dreyfus model as applicable to the work of coaching. Specific findings affirmed the usefulness of the model in understanding the journey to mastery for the coach:

The developmental progression that Dreyfus and Dreyfus outlined provides a pathway and a source of encouragement for leaders who enter the field of coaching. It is reassuring to know that in the initial stages of development, a hyperfocus on balancing skills, use of self, and a sturdy methodology is often awkward and challenging. The developmental pathway is particularly helpful in providing a broad lens for the natural progression that evolves through time and practice for the coach.

Finally, the work of Mihaly Cziksentmihalyi (1997) provides yet another perspective on one’s learning journey with a particular focus on what is required in order to maintain a state of flow when a practitioner has reached a state of mastery (see his model in Figure 21.2).

Cziksentmihalyi’s model maps the natural progression of skill development relative to the feeling state of the individual. When skills are low and the challenge is high, as is the case for the novice or the conscious incompetent, anxiety and worry are pervasive. When one moves to Dreyfus and Dreyfus’s stage of proficiency or Howell’s conscious competent, it likely aligns with Cziksentmihalyi’s arousal state. The well-known flow state comes with mastery when intuition and a sense of unconscious competence dominate. An additional element in this model is the waning side of the cycle, when the challenge of the work is no longer sufficient to keep the individual fully alive and engaged. This can easily happen to any coach who continues to coach without challenging her own development through structured supervision, peer supervision, coaching, and ongoing development.

This model is equally helpful to novice coaches because it highlights the normative nature of worry and anxiety when skills are low and motivation is high. Cziksentmihalyi’s model is equally useful on the waning side where the skills are at a peak and the challenge is waning. The coach who reaches this plateau needs to be able to easily identify this (not at all unlike the doldrums of the cycle of renewal) and use this as a signal to make some adjustments in order to get into flow.