4

Beginnings without End

Derealizing the Political in Battlestar Galactica

In its coercive universalization, however, the image of the Child, not to be confused with the lived experiences of any historical children, serves to regulate political discourse—to prescribe what will count as political discourse—by compelling such discourse to accede in advance to the reality of a collective future whose figurative status we are never permitted to acknowledge or address.

—Lee Edelman, No Future

“Hi, honey, I’m home. You kill me. I download. I come back. We start over.”

—Leoben (Callum Keith Rennie) to Kara Thrace (Katee Sackoff), Battlestar Galactica, “Occupation”

The transformation of the political field that continues to elude us by and large in the register of theory confronts us in persistent if uneven (and unevenly suggestive) ways on the terrain of popular culture. In this chapter, I turn to the television series Battlestar Galatica for its narrative elaboration of what Michael Hardt designates (in an essay I discuss in chapter one) as the simulacral social relations that appear with the real subsumption of labor under capital and “the withering of civil society.” However, the analytic categories in which Hardt traffics offer little sense of what this designation might mean at the level of social subjectivity and quotidian experience. What are the scenes and the circuits, the idioms, and the affects that structure this virtual sociality? In Battlestar Galactica, I find an intricate and generative rendering of the transit from civil to simulacral society, from discipline to control, from normative culture to whatever it is that emerges in its stead—the serial culture I invoked, provisionally, near the end of chapter 1. The White Boy Shuffle asks what the unraveling of political modernity signifies for social movements and the practice of resistance; Battlestar Galactica invites us to consider what this sea change entails for social accommodation and the practice of domination. If Beatty’s novel meditates on the passing (for better and for worse) of freedom politics, Ronald Moore’s series dwells on the eclipse of a realist politics, secured through the regulative figures Lee Edelman describes—through the cultivation of common referents and attachments on a mass-political scale.

Battlestar Galactica aired in the United States from 2005 to 2009 on the SciFi channel, garnering fans and fan cultures that traversed the political spectrum, at least until the opening of the third season, when its allegory of the Iraq occupation disenchanted its right-wing adherents. A remake of the 1978 series of the same title, the new series, like its predecessor, is a generic space opera; its story line pivots on the antagonisms and intimacies of biological humans and their synthetic counterparts, the cylons, whose merely simulated humanity registers in the aliases by which the humans know them: “skinjobs” and “toasters.” As much as the series seems poised to pursue a familiar set of preoccupations with the limits of humanity and the affirmation of humanity at its limits—preoccupations that certainly inform the series in its entirety, and especially in its initial two seasons—I will suggest that the formula is heavily inflected towards a consideration of political formation in the present, “neoliberal” moment. In this regard, it seems to me, the series sustains a canny, if not always coherent line of reflection on contemporary political rationalities, the social constitution of political subjects, the (de)composition of the body politic, and the production of its collective future(s). On the whole, I will suggest, this line of vernacular reflection outstrips political theory in the always and necessarily lurching and fragmentary effort to think the historical present. Indeed, what I have come to value most about the series is its decidedly partial and ephemeral grasp on its organizing figures and motifs, the very thing that prompted anxious fans to worry from the get-go whether the series’ writers were flying blind or following a plan.

Unsurprisingly, the more an encompassing narrative plan emerged toward the end of the third and especially in the fourth season, the more apparent it became that the writers had no idea how to corral the narrative elements they had put into play. As a result, the fourth season was caught up in a frenetic drive to closure, marked by a series of revelations and arrivals that were, by turns, tacky (a character mysteriously returned from a fatal crash is “revealed” as an “angel of God,” for example) and nonsensical.1 The more interesting point, however, is not that the writers failed to bring the narrative to closure adeptly, but rather that the series limns something of the present shift away from foundational assumptions about the modern political field—assumptions about the aims of power and the collective bodies through which it acts, to be sure, but also, and crucially, about the temporality of political life, such that any move to narrative closure, to the moment of ending, or attainment, that measures the passage of progressive time, will necessarily feel like a violation of the series’ own best intuitions. To some extent, of course, a television series is always an elusive and incomplete object. What is the series? The episodes aired, in weekly installments, with extended pauses between seasons, interruptions marked by the convention of the prefatory recap? The episodes viewed consecutively on DVD, over the limited span of a few days or weeks? About which of these Battlestars do I intend to make claims? The question is finally undecidable: both and neither one, exclusively. But I want to argue that in the case of Battlestar Galactica, the episodic form of the television series lent itself to a speculative engagement with the emergence of political imaginaries and practices that do not align with the linear temporality of realist narrative, to which the series’ writers nevertheless remained substantially, if awkwardly committed.

In other words, I want to read the possibilities that inhabit the series’ “failures,” as they call into play the “reproductive futurism” Lee Edelman discusses, where the contours of the political field (“what will count as political discourse”) are drawn in relation to a projected moment of compulsory arrival. For Edelman, what matters is the transmutation of the figural into the fixed through the agency of the iconic “Child.” Thus a possible figuration of the future is arrayed as the reality of an already accomplished destination.2 This aspiration to the plenitude of an immediate world yields the most mundane of ideological achievements: the installation of fantasy as reality. “Though the material conditions of human experience may indeed be at stake in the various conflicts by means of which differing perspectives vie for the power to name, and by naming to shape, our collective reality,” Edelman concedes, “the ceaseless conflict of their social visions conceals their common will to install, and to install as reality itself, one libidinally subtended fantasy or another, intended to screen out the emptiness that the signifier embeds at the core of the Symbolic” (2004, 7–8). In this view, the work of all politics and its ruse is to “shore up a reality always unmoored by signification” (2004, 6), to install affecting figures as limiting truths, a foundationalist agenda to which the most revolutionary politics remains bound. “For politics, however radical the means by which specific constituencies attempt to produce a more desirable social order, remains, at its core, conservative insofar as it works to affirm a structure, to authenticate social order, which it then intends to transmit to the future in the form if its inner Child” (2004, 2–3). Over and against this realism, Edelman posits queerness as that which “must always insist on its connection to the vicissitude of the sign” (2004, 7). This queerness is not oppositional, in the sense that it is not a political position at all; rather, it is a figure for “the resistance, internal to the social, to every social structure or form” (2004, 4). Where the Child is the signifier of the transmissible future, “queerness names the side of those not ‘fighting for the children,’ the side outside the consensus by which all politics confirms the absolute value of reproductive futurism” (2004, 3).

Battlestar Galactica stands in a curiously doubled relation to “reproductive futurism,” at once a monument to its logic and a decisive counter to Edelman’s account of politics’ realist aims. On the one hand, the figure of “the Child” presides over the series’ narrative, although it is less the human victims of the cylon genocide who are fixated on posterity, than the cylons themselves.3 In the wake of their nuclear attack on the twelve human colonies—an attack that reduces the human population of twelve worlds to fewer than 50,000 people—and over the course of four seasons, the cylons will demonstrate a rather dizzying array of ambitions in relation to this residual humankind, ranging from isolationism (preserving cylon culture against human influence) to détente (the cooperative pursuit of shared objectives) to domination (the imposition of cylon rule on the interned human population), but none more consistently than the ambition to secure the shape of the cylon future by doing with humans what they are unable to do with one another, namely procreate. Oddly enough, the characters repeatedly attribute the imperative to procreation to “the cylon god,” an entity originally construed and revered by the centurions, who are the humanoid cylons’ robotic (that is to say, inorganic) predecessors. Cylon society, then, is marked by an attachment to the figure of “the Child” that is only enhanced, or so it seems, by the absence of actual children. On the other hand, cylon politics as figured in Battlestar Galactica do not participate in the authenticating project Edelman attributes to all political imaginaries, on the Right and on the Left. Rather, what interests me about the series is that the value and, indeed, the efficacy of the “libidinally subtended fantasies” that comprise cylon life are not in any sense conditional on the fantasy of their actualization. On the contrary, the narrative suggests that the cylons’ “ceaseless” and “conflict[ed] social visions” are not proffered as representations of real social relations at all, but quite explicitly as simulacra, as separate planes of sociality that are not integrated into a consensual reality—and, more to the point, perhaps, do not compete for the authority to integrate a body politic.

This chapter considers Battlestar Galactica as an allegory of our own historical situation in Walter Benjamin’s particular understanding of the term, where allegory breaks apart the world, renders it in ruins. I read cylon society as a vernacular gauge to the something else that appears, piecemeal, amid the failing institutions of modern politics, represented in the series by human society, as it reforms in the aftermath of catastrophe. In Battlestar Galactica, this residual humanity adheres in bad faith to the institutions of the modern political field (popular sovereignty, rule of law, separation of powers), while the cylons, I will argue, are a narrative means to discern the simulacral politics into which “we” in the United States—though elsewhere, too, no doubt, in uneven, regionally and locally differentiated ways—are now emerging. The series’ humans are “us,” in other words, and the cylons are “us,” too. But the cylons dwell at the limits of the narratable, an index to a sea change in the practice of government that is still unfolding, to a novel organization of political power that we know how to gauge only by reference to the criteria of legitimacy, reason, and coherence that this emergent order displaces. To revert for a moment to Edelman’s Lacanian idioms, I will suggest that the cylons are a representation of a political power that is not dedicated to “shor[ing] up a reality always unmoored by signification”—as well as a representation of the kind of subjectivities this non-realist power demands and cultivates.4

It may seem like a sufficiently obvious claim that not all power participates in the foundationalist agenda Edelman assigns to politics as such. Doubtless, many on the Left today would be quick to challenge Edelman’s claim that all political projects function to authenticate. Such challengers might cite the idea of a radical democratic politics, which insists that the contours of the political subject can never be decided in advance and that democracy entails a radical openness to a never pre-scripted futurity. Edelman himself champions a similar politics of radical contingency (under the sign of “queerness”), though he tends to present this as a political non-position (or a non-politics). But quarrels with the totalizing quality of Edelman’s Lacanianism aside, it is certain that the Left (queer and radical democratic alike) invariably understands the forms of power it rejects as securing “in advance . . . the reality of a collective future.” We may embrace a queerness heterogeneous to political order as such, or we may mobilize under the banner of a radical democracy that validates contingency and mutability as alternate principles of political life, but either way, we assume that the power we oppose operates, by contrast, to fix social and political relations and produce a readable world. Within contemporary left imaginaries, in other words, anti-foundationalism appears on the side of (genuinely) revolutionary political impulses, and not on the side of institutionalized political power, which labors, inevitably, or so we imagine, to establish its own necessity in the way Edelman describes, by “authenticat[ing] social order.”

Whether or not—and to what extent—such assumptions about the realist character of political world-making are any longer tenable is a central question of this book. This chapter reads in Battlestar Galactica an attempt, admittedly uneven and occasionally inchoate, to explore—on the fictional terrain of cylon society—emergent forms of domination and control that proceed, not by “affirming a structure,” but by derealizing the political field. Relatedly, the series asks how the commonplaces of modern political discourse carry over into this derealized politics, since conspicuously (in the series as in the world), the new practices of government seem less to generate novel political idioms than to compulsively recycle the old. So across the spectrum of political discourse, we continue to encounter the iconic Child, as Edelman is surely right in remarking. But does the figure of the Child demonstrate political power’s historically constant refutation of its own figurality, as Edelman suggests? Or does the figure of the Child, in our own world as in the world of Battlestar Galactica’s cylons, persist only as a fantasy of a different order, one that erodes our relation to the body politic, rather than sutures us to its (our own) collective future?

The Models

In the pre-story of Battlestar Galactica’s post-apocalyptic narrative, humanity’s robotic creations, the cylons, rebel against their human masters and are banished to another world. For several decades, all contact between the cylons and the twelve human colonies ceases, until the cylons unleash a nuclear holocaust on the home planets of their human creators, and the survivors flee these radioactive worlds aboard a ragtag assembly of interstellar vessels, presided over by the last remaining war ship, or “battlestar,” Galactica. In the interim between their banishment and their spectacular reappearance, we come to learn, the cylons have “evolved” from their original robotic form into synthetic organisms, indistinguishable from their biological human counterparts. One of the first season plot lines hinges on the efforts of the human scientist Gaius Baltar to devise a “cylon detector” that would differentiate humans from cylons on the basis of blood or other physiologically measurable criteria, and so identify cylon infiltrators on board the humans’ ships. Baltar’s efforts are unsuccessful, and he eventually abandons this work, which loses importance, in any case, as humans confront the serial form of cylon embodiment: there are twelve cylon models (the seven models that comprise existing cylon society, and the missing “final five,” who resurface in season 4), and all cylons have the identical body to others of their model. In other words, each model represents a genetic template that yields thousands (perhaps tens of thousands) of iterations, or clones, and because of the limited number of models, the handful of infiltrators are sooner or later exposed, as their exact bodily doubles start appearing elsewhere in the fleet.5

Apart from bodily identity, however, the relation among the iterations of a particular model is harder to specify. Identical genetic material entails not only identical embodiment, but also core personality, all the more so as cylons enter the world fully formed, as linguistically competent “adults.” There is no interval of cylon development—no cylon childhood. As a result, it is not usually possible to distinguish between the iterations of a model on the basis of speech patterns, mannerisms, or forms of performative embodiment, any more than on the basis of physical appearance. The difficulty of distinguishing among iterations is exacerbated by the circumstance that when infiltrator cylons living in human society acquire names, the name routinely slips into general usage for the entire model. Thus, for example, after the Galactica pilot Sharon Valeri is revealed to be a cylon “sleeper agent,” the name “Sharon” gradually becomes an accepted designation for all the model Eights (as in, “the Sharons,” or “a Sharon”), just as the model Ones become the Cavils, after the identity assumed by one of their line, who poses as a human priest, Father Cavil. To a certain extent, the clones’ apparent identity secures the narrative’s intelligibility, by allowing the viewer to proceed as though the Sharon in one scene is the same character as the Sharon in another—even as we are compelled to know that this is not necessarily so. At the same time, however, the clones are designed for “evolution”—with an inbuilt propensity for learning and adaptation, so that different experiences produce differences in intellectual and affective disposition. Although early in the series the cylons are sometimes described as “programmed” for a particular function—for example, when Sharon Valeri suddenly awakens to her cylon identity and attempts to assassinate Galactica’s commander, we are told that her “programming triggered” in terms that suggest that the clones operate according to a fixed set of protocols and proclivities—the clones are also represented as capable of adapting and altering their own programs. Insofar as cylons are “programmed,” they are programmed for learning, flexibility, and receptivity to new and varied forms of relation. In fact, this receptivity is precisely what distinguishes the “evolved” models from their robotic predecessors, the centurions, whose “heuristic programs,” we are told, are strictly limited by the imperative that they carry out the evolved models’ commands. The programmed centurions are relegated to the performance of lower-level military and security functions, and never once in the series does any of them figure narratively as persona.6

By contrast, the clones’ adaptability tends to play out narratively as a capacity for individuation, although (as I consider farther on) this is not a particularly apt way to conceptualize cylon personality. Across the narrative arc of four seasons, several of the clones assume seemingly discrete identities. There is “Caprica,” the model Six who seduces the scientist Baltar and thereby gains access to the security codes for the humans’ defense grid, an act that makes possible the cylon’s devastating nuclear ambush (ironically, this model Six is named for one of the human home worlds that she was instrumental in destroying). Her name remains exceptional (not shared with the rest of her line), but rather, as one of the model Threes observes, a mark of this particular iteration’s “unique” achievements. Similarly, after Sharon Valeri rejoins the cylons, she is (intermittently) differentiated from her sister “Sharons” through the use of her pilot’s call sign, “Boomer.” More ambiguously, in season 3, one of the model Threes, or D’Annas, enters on a spiritual quest to identify the unknown “final five” cylons (despite their designation as “final,” these cylons are thought to be the original models and creators of the rest of the line), which involves repeatedly staging her own near-death, as this liminal state triggers her vision of the creators’ faces. Her quest to know and to reveal their identities seems uniquely hers—not the D’Annas collective mission—even though, as a consequence, her entire “line” is punitively “decommissioned” by the infuriated Cavils.

We might say that cylon society neither requires (teaches) nor forecloses (represses) individuality (or something that looks like individuality), but rather that it appreciates differentiation—in both senses of the term, that is, “values” and “evaluates” it. In the wider context of the series’ narrative, Caprica’s worry that she and Boomer represent “dangerous celebrities in a culture of uniformity” is at least partially misleading—one of the many moments when the script seems to misrecognize the elements that the series has put into narrative play. The “uniformity” of cylon culture is not, as the term usually suggests, the (unstable) achievement of a socializing apparatus that cultivates identity from the polymorphous attachments and recalcitrant particularities of (human) subjects. Nor, for that matter, is cylon “uniformity” a normative identity, which itself produces the aberrations it would regulate. On the contrary, “uniformity” is not a cylon norm at all, but an effect of the apparent flattening of difference in a society of serial production, of proliferating managed differences. These include both the differences within models and the differences among them, which are regarded by the cylons themselves as productive variations and potential risks. But the myriad aesthetic, intellectual, and affective differences among cylons are assessed as benefit or potential threat, not to the purity or authenticity of cylon culture, but simply to the efficient functioning of cylon society, as determined by whatever faction of cylons (usually though not always an alliance of several models) is able to assert and enforce their view. The criterion for risk assessment, in other words, is tactical, not moral. So for instance, the Cavils decommission the Threes not because D’Anna’s quest is a violation of a cultural prohibition against speaking of the final five (although such talk is, in fact, prohibited), but precisely because her quest has assumed an existential and a moral, rather than a tactical character:

Cavil: Your model is fundamentally flawed.

D’Anna: No . . . it’s not a flaw to question our purpose, is it? To wonder who programs us the way we think and why?

Cavil: Well, that’s the problem right there. The messianic conviction that you’re on a special mission to enlighten us. Look at the damage it’s caused.

D’Anna: I would do it again.

Cavil: Yes, I know. That’s why we’ve decided to box your entire line. (“Rapture,” 2007, Season 3)

Cavil’s quarrel is not with any particular interpretation of the founders’ intentions, but with the very nature of the quest itself: to discover and disseminate the moral grounds of cylon culture. And D’Anna’s offense is not her deviant beliefs, but her very preoccupation with the register of belief (with origins, identity, and right). Paradoxically, then, the “uniformity” of cylon culture marks the absence of an integrative norm (and attendant strategies for pathologizing and policing deviation) in a society sustained through the multiplication, archiving, and risk-assessment of differences at different scales (models, clones).

Both the proliferation and management of difference are sustained through cylon technologies of “organic memory transfer.” In an arrangement the humans routinely produce as evidence of the cylons’ fundamental inhumanity, the physical death of a cylon triggers not only an automatic download to an identical new body, but also, along the way, the uploading of the “dead” cylon’s consciousness to a shared database. This means both, as a “resurrected” Sharon Valeri puts it, that “death becomes a learning experience” and that memories are readily and routinely transferable across “individuals.” So, for instance, what a Three extols as Caprica’s unique “experience of seduction,” which no other cylon has ever had, is also, following Caprica’s death and download, an experience fully accessible to other Sixes—if not to other cylons more generally. (The series offers multiple examples of file-sharing among iterations of the same model; it does not expressly resolve whether such transfers are possible across models.) The implications of this file-sharing are highlighted in an episode from the fourth season, when the Galactica crew member Hilo finds himself part of a human delegation to a cylon base ship. On board Galactica, Hilo has married an Eight, the only cylon among the seven known models who has opted to live with and as a human, and the two of them have produced the first (and only) half-human, half-cylon offspring, named Hera. Like the infiltrator Sharon, Hilo’s wife is a pilot, and the other pilots initially want to assign her the call sign of that other iteration, “Boomer.” This Sharon demurs, noting that “she [Boomer] was someone else,” and another pilot proposes the call sign “Athena” instead. On the base ship, Hilo is assigned to work closely with yet another Eight, and during a lull in their labors, as Hilo stretches painfully, the Eight comes over and begins to massage his back. Hilo pulls back, bewildered:

Hilo: Athena, my wife, she learned to do that. She never did that when I met her. [Studies the Eight’s expression.] What?

Eight: I got curious about Athena, about her and Hera and you. So I accessed her memories from her last download.

Hilo: You have her memories?

Eight: They’re mine now, too. They’re as real as my own. I know this must feel like a violation of trust, or something. But I don’t want it to be strange. Ok?

Hilo [haltingly]: Right, right sure. (“The Hub,” 2008, Season 4)

This exchange disallows the inclination to read the clones as physically identical but psychically differentiated “individuals” and, conversely, to collapse the distinctions between clones, viewed as so many physical manifestations of a singular, hive mind.

The clones are both differentiated and lacking psychic interiority, so that Hilo’s interlocutor in this scene is not his wife, but at the same time the memory archive that constitutes “Athena” is not proper to his wife—not her psychic property. Cylon society, then, is premised on the unraveling of interiority that Gilles Deleuze associates with the transition from “disciplinary societies” to “societies of control.” “We no longer find ourselves dealing with the mass/individual pair,” Deleuze writes. “Individuals have become ‘dividuals,’ and masses, samples, data, markets, or ‘banks’ (1990, 2, emphasis in original). In its framing of serial cylon production and downloading of cylon consciousness, the series might be understood as taking up and literalizing Deleuze’s figures, particularly in the way that the iterations inhabit differentiated (“divisible”) but not discrete or enclosed psychic territory.

The cylons’ “dividuation” provides an important context for understanding the humans’ markedly racist attitudes towards cylons, whom they routinely denigrate as “skinjobs” and (bizarrely) “toasters.” With respect to more familiar racial categories, the composition of both cylon and human society is moderately multiracial (and multiethnic): most of the characters (and of the ensemble cast) are Euro-American, with a handful of main and supporting roles (both cylon and human) played by Asian, South Asian, black, or Latino actors.7 Conversely, both cylon and human society feature an intact white/Euro-American majority (so that the racial demographic of both the cylon and the human ships are a rough correlate, say, for that of an upper-middle-class urban neighborhood in most U.S. cities today). On the cylon side, there is no suggestion of intra-cylon racial antagonism (no suggestion that differences in skin colors are regarded as anything other than an aesthetic variation). On the human side, the reigning ethos is pervasively multiculturalist, although there are occasional intimations of past racial and (or) ethnic tensions, particularly among the different human home worlds.8 Instead, the humans’ overt and socially sanctioned racism is directed at the (majority white) cylons, in a move that reproduces the familiar associative logic of the colonial imagination: racial difference (non-whiteness) signifies inhumanity, inauthenticity (that is, a merely mimetic relation to the human), and by extension the machine (especially, of course, the android, the machine replica of the human). In the series’ imagined confrontation between humans and cylons, the direction of the associative chain is reversed, so that the whitest of cylon skin tones is (re)coded as only a “job.”9 However, the humans’ racialization of the cylons also registers their tenuous relation to interiority, to the property in the self that historically distinguishes modern wage labor from the slave, the serf, and other forms of indentured (unfree) labor. If wage labor depends on the worker’s inalienable property in the self (cathected as “soul,” what cannot be bought or sold in the marketplace), “race” appears in the colonial (and settler colonial) contexts as the mark of the dispossessed—those without claim to a (putatively) inalienable/inviolate interiority.10

Crucially, as the series explores, the cylons’ lack of bounded interiority, or more exactly, the absence of an organizing cultural fiction of proper identity, erodes the distinctions—for example, between originals and replicas, between first- and secondhand experience, between real and fantasized objects—on which the production and policing of social reality depends. In one of the earliest plot developments to foreground the relation between “dividuated” cylon identity and its derealizing effects, Caprica’s death, in the explosion that levels the planet for which she is named, triggers both her resurrection in a new cylon body and her curious resurrection as a kind of phantom companion to Gaius Baltar, who survives the holocaust and succeeds in escaping his devastated homeworld. Fans of the series refer to this phantom as “Head Six” (as she exists only in Baltar’s consciousness), which is perhaps a better name, since this presence seems (unlike a phantom) quite physically tangible to Baltar himself. He not only converses with her, but carries on the sexual relationship that he originally had with Caprica. However, no one else on board Galactica perceives Head Six (a circumstance played to comic effect in one episode when senior officers walk in on Baltar’s climax with this invisible lover). In a parallel development, Caprica downloads into her new body with a Head Baltar in tow, although Head Baltar is less developed as a character and tends to drop out after the first two seasons, while Head Six remains a salient presence in Baltar’s life throughout the series. Although Caprica appears unperturbed by Head Baltar’s presence, if sometimes distracted and annoyed by him, Baltar is notably disturbed and bewildered by Head Six’s companionship. “What are you?” he demands of her at one point. “Connected to the woman I knew on Caprica, or a damaged part of my subconscious struggling for self-expression?” Head Six’s curt reply does little to resolve Baltar’s uncertainty—“I’m an angel of god sent here to help you, just as I have always been,” she snaps—precisely because she refuses the dichotomy on which Baltar’s question depends (“Torn,” 2006, Season 3). As Baltar sees it, the twin possibilities are melancholic fixation (incorporation of the lost object) or imposition (an assault on his psychic integrity by an external force, his sometime cylon lover). Either Head Six is his own psychic handiwork, or a ‘real’ expression of Caprica (and of her investment in him). But in its refusal to resolve this question—except by way of the writers’ peculiar homage to Wim Wenders (which is also the only narrative foray into magical realism)—the series tends to suggest that the Head characters are neither hallucinatory nor real, neither the psychic property of the one who sees them, nor proper manifestations of the persons whose identities they mime. Rather, they intimate an alternate psychic topography, in which Head Six is no more or less a “real” person than Caprica, “herself” an iteration of a simulacral personality that has no authentic embodiment or proper place.

From a cylon perspective, Baltar’s perception of Head Six is not an index of pathology, but an exercise in choice, one that cylons make on a daily basis, as they construct the world in which they move. “Cylon society is based on projection,” Head Six explains. “It’s how they choose to see the world around them. The only difference is you choose to see me.” Caprica later expands on this fragmentary explanation in a conversation on board a cylon base ship, to which Baltar has fled after collaborating with the cylons in their brutal occupation of the human settlement on the planet New Caprica. Living among cylons, Baltar confronts not only his fundamental incomprehension of their social and psychic world—the continual misfire of his attempts to build intimacies and alliances—but also, relatedly, his misapprehension of the base ship’s design. He complains to Caprica that he finds himself constantly lost, unable to distinguish one passageway from another, as none of them seem to bear any differentiating marks, to which she responds that the ship is featureless because cylons design their own environments:

Caprica: Have you ever daydreamed? Imagined you’re somewhere else?

Baltar: I have a very active imagination.

Caprica: Well, we don’t have to imagine; we project. For example, right now, you see us standing in a hallway, but I see it as a forest [camera cuts to Caprica’s viewpoint] full of trees, birds, and light . . .

Baltar [cuts in]: Like the walks you and I used to take on Caprica.

Caprica: The aesthetics give me the pleasure, not the specific memories. [Camera cuts back to ship’s bare hallway; a Five strolls by and eyes them]. Instead of staring at blank walls, I choose to surround myself with a vision of god’s creation. (“Torn,” 2006, Season 3, my emphasis)

In one sense, of course, we might say that human psychology is also “based on projection,” at least insofar as the human relation to the world is mediated by signifying categories that we misrecognize as the given objects and contours of the “real” world. But for the series’ human protagonists, as for Lacanian analysis, this misrecognition appears as a necessary and constitutive dimension of human sociality. Cylon projection, by contrast, renounces the investment in a collectively verified world. Cylon realities are explicitly conventional, a matter of how cylons choose to see, and since there is no reluctance to acknowledge reality’s “figurative status,” to recall Edelman’s formulation, there is also no reason to require that all cylons inhabit the same figurations. Caprica’s hallway forest is neither a “real” place, nor even the loving reconstruction of a “real” location, but a “daydream” or “vision”—an elsewhere assembled from a sensory archive coded for aesthetic value. In other words, the space of their base ship—and of the various planetary surfaces to which they lay claim—is experienced by its cylon occupants as a series of customized simulations.

If the iterative form of cylon identity, and relatedly, the “banking” of cylon consciousness, means that there is no privatized psychic space, cylon society is also shaped by the reciprocal absence of public spaces. Certainly, projections can be shared among cylons (although the series tells us little about how often or routinely they do so). Boomer, for example, shares with her former human lover Tyrol (since revealed as one of the “final”/original five) her projection of the house they once intended to build together, before the cylon attacks, when they both still believed themselves human. Later, when Boomer has abducted the child Hera, Tyrol seeks her out but fails to find her in their simulated house, in a turn that suggests that projections might be transferrable in much the same way as memories. Tyrol’s access to the projection does not seem to depend on Boomer’s renewed invitation, or even on her conscious “presence” there, since the house stands intact, even in her absence. But if projections are not (like human daydreams) ultimately private, neither are they public, since the very proclivity to project dismantles the experience of an anonymously collective social space. Six’s discussion of projection provides a narrative appraisal of (what we see) of the base ship’s design, a rhizomatic space of corridors and junctures, seemingly without contexts for congregating. The comparison to Galactica (and, arguably, to every imagined human spaceship from the cramped and industrial Nostromo to the sprawling, corporate Enterprise and beyond) is telling: the battlestar set includes a command deck, a bar, an officer’s common room, the pilots’ briefing hall, as well as other spaces for public assembly—and one can scarcely imagine how the script could develop the motifs of human sociality in the absence of such public settings. By contrast, the cylon base ship appears to have no operational nerve center and no recreational commons. There are rarely more than three or four cylons present together in any particular scene, and the open spaces on the ship are devoid of any fixtures (tables, chairs, benches, consoles) that would suggest contexts for gathering. On the base ship, the de-privatizing of consciousness corresponds with the miniaturization of social life: the reduction of the social to the scale of micrologies.11

The Body Politic

I have been arguing that in the figure of the cylons, Battlestar Galactica elaborates a contemporary shift from disciplinary society to a “society of control.” As thematized in the series’ representation of cylon subjectivities, this shift is marked by an externalization of psychic life (unmoored from its proper interiorized spaces), in particular through archiving technologies that encode “memory” and “consciousness” as transferrable data. At the same time, within the scenes and contexts of cylon society, the “external” world is fragmented, miniaturized, and derealized. If “dividual” cylons lack interiority, cylon society lacks an (imagined) “core,” including a set of integrative cultural “values,” institutions of social and political belonging, and an architecture of public life. In this section, I take up more specifically the effect of these absences, as well as the forms of political life—the structures of control but also the imaginaries, aims, and attachments—that emerge with the disappearance of the modern political field.

Despite its staging of the human/cylon conflict as a conflict between peoples and ways of life, an interpretation of events on which the humans tend to insist, the series rather conspicuously declines to envision the cylons as an organic social body, realized in traditions, institutions, discourses. Although the cylons briefly decide that “instead of pursuing our destiny, trying to find our own path to enlightenment, we hijacked yours,” as Cavil puts it (“Lay Down Your Burdens,” part 2, 2006, Season 2), it is unclear how—on the basis of what beliefs, practices, or institutions—they might produce a sense of their “destiny” as a people. (And indeed, the decision to go their separate way is short-lived, since a scant year later, the cylons invade the human settlement on New Caprica and establish a cylon-controlled puppet regime.) The figure of the Child to which most of the models remain deeply attached (Cavil is a vocal exception) crafts an apparent destiny only at the expense of wedding cylons to humans, of a “highjacking” that (not incidentally) entails a genocidal assault on humanity. And no matter how keen their investment in the icon, cylon society includes neither term in the relay of “family” and “nation” that the figure of the Child is intended to secure. While cylons refer to each other as “brothers” and “sisters,” a choice of terms seemingly intended to foreground the lateral, rather than hierarchical organization of cylon society, there are no cylon children, no cylon pedagogies, and no practice of cylon domesticity—a situation brought into relief when the cylons remove Hera to the base ship, only to discover they have absolutely no idea how to assimilate a child. In that episode, we see Hera standing in her plain white crib, the only object in a cavernous, unadorned white room; Boomer stands next to her, an exact visual duplicate of the child’s mother, Athena, but unable to offer comfort, to fathom what it might mean to make the child “at home.” Moreover, despite the echoes of a nationalist imaginary in the reference to fraternal and sororal relations, nothing is in place to enable the reproduction of those relations in the event of conflict. There are no laws—at least, none that cannot be summarily cast aside—no structures of mediation, no apparent means to hegemonize. Although the violent conflict that erupts among the models in season 4 is framed as a cylon “civil war,” it seems to represent not so much the decomposition of a body politic, as the consolidation of alliances among the models. In this context, “family” cannot serve as the naturalized basis of a national people, any more than “nation” can guarantee the greater meaning and continuity of “family.”

At least at first glance, it appears that the iterative nature of cylon subjectivity obviates the need for an elaborated governmental apparatus. Since the consensus of each “line” is taken as given, a single representative of every model casts a vote; the seven votes are tallied, and the majority wins. From this perspective, the seven members of a voting quorum are not so much representatives of cylon society (not an abstraction or abridgement of the body politic), as the actual embodiment of the masses. However, as we discover, voting is a customary, rather than a legal arrangement, or more exactly, perhaps, there is nothing to uphold the authority (and legality) of the law. Initially, when the rogue D’Anna (on her quest to reveal the five) refuses to abide by the outcome of a vote, the participating Sharon is incredulous. “She defied us! Defied the group,” Sharon exclaims, while Six agrees: “It’s like we don’t even know them anymore.” If D’Anna’s defiance is truly unprecedented, as Sharon’s outraged response suggests, hers is a form of unlawfulness to which, it seems, no lawful response is possible. The Cavils act unilaterally to decommission her line, and while the other models do not interfere in his punitive agenda, they have also not voted to assent to it. Once put into play, it appears, the prospects for unilateral action—for acting in defiance of or apart from “the group”—proliferate unchecked. Shortly after D’Anna’s shocking insurgency, the Sixes, in alliance with the Leobens and the Sharons, defy the move by Cavil and his allies to “reconfigure” (and in the process “dumb down”) the centurions (interestingly, in the interim, the boxing of D’Anna’s line has introduced the possibility of a tied vote). “You have no authority to do this,” Cavil rails against the insurgent Six; “You can’t do anything without a vote.” “No, we can’t do anything with one,” the Six replies, “so we’re done voting” (“Six of One,” 2008, Season 4). Moreover, in the vote to reconfigure, the tie-breaker is cast by Boomer, who declines to fall in line with the rest of her sister Sharons, opting instead to exercise an individual vote on the side of Cavil’s alliance. In this context, the Six is outraged, while Cavil seems perfectly happy to argue against the authority of convention:

Six: But no one has ever voted against their model. No one. Is this true [that Boomer has broken rank with the other Eights]?

Boomer: We must be able to defend ourselves.

Six: No, this is unconscionable. This is wrong. She can’t. [To Cavil] You had something to do with this!

Cavil: No, it was her decision.

Leobon: There is no law, no edict, nothing that forbids it, it just never happened before.

Six: Try to remember you said that when he boxes your line. (“Six of One,” 2008, Season 4)

If there are no margins—no concealed or semi-concealed spaces off the grid of surveillance and control—there is also no center. What initially appears as the (un)natural organicism of cylon society, as the programmed consensus of the clones, turns out to be a short-lived idyll. When the vista of unilateralism suddenly opens, there is no means to counter it—nothing of the discourses and institutions necessary to cultivate and sustain the life of the social organism, nothing to secure the reproduction of the political order.

On this point, the contrast to the human government-in-exile is marked. The institutions of human government are represented in the series as having been reconstituted on a largely ad hoc basis in the wake of calamity. As a result, the power of the executive branch has been inflated, while the members of the representative body are factionalized and mutually hostile. The executive branch is quite literally in bed with the military, as President Laura Roslin pursues an affair with Galactica commander Bill Adama, which endures to the series’ end. But when Roslin decides to falsify polling results so as to secure her reelection, a number of discourses and institutions intervene to remediate the significance of her action. Most obviously, Roslin’s scheme ultimately fails to deceive the authenticating protocols (and personnel) put in place to secure the election’s legality. The scheme very nearly succeeds, and the writers are not so sentimental as to imply that attempts to steal elections are invariably foiled in (what count as) democratic societies. But the episode nevertheless serves to insist that the authority of the legal order exceeds every attempted violation—even (perhaps especially) those that might go unchecked. In the diminished political institutions of a residual humanity, the foundations still hold, or more exactly perhaps, the ruse of the foundationalist imaginary persists, and we “accede in advance to the reality” of a legal order that has already determined the meaning of the actions against it. Interestingly, too, it is Adama who confronts Roslin with the evidence of the crime. What Roslin wants to present as a legitimate (if illegal) act in defense of the polity, Adama redescribes as a “cancer” that will “move to the heart” (“Lay down Your Burdens,” part 2, 2006, Season 2). Adama does not make explicit whose body is threatened by this illness—presumably, it is the collective body of a surviving humanity to which he refers. But since Roslin is herself battling cancer, Adama’s trope also works, more subtly, to position her compromised system as a synecdoche for the body politic and thereby to align Roslin, not with the invading cancer, but with the battle against it. Unlike cylon democracy, the humans’ democratic government does not unravel when the outcome of a vote is (very nearly) dismissed, not because human democracy is less precarious in practice, but because of institutions (the law) and imaginaries (of leadership) that have already scripted the crisis from the standpoint of an achieved “democratic society.”

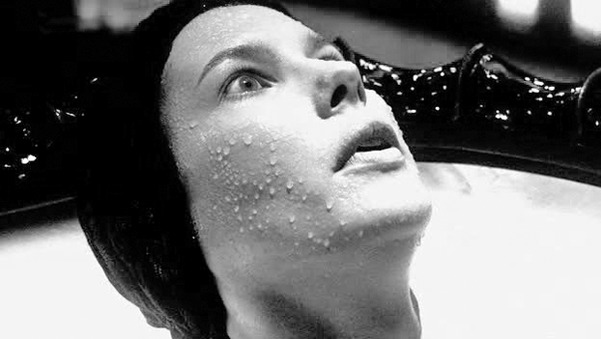

Aside from its framing of group decision-making, the series provokes us in other ways to attribute an integrity to cylon society that the narrative subsequently belies. If cylons are not disciplined, they are certainly bound to an informational network that fully opens their psychic life to surveillance and control. Although we are never explicitly told how this network functions, the interface seems not to require any technological prosthesis—no keyboard or control panel, but arguably, too, no implants either. Rather, the ship’s systems appear at least partially organic in nature, and the clones access its database by submerging their hands in basins of a viscous fluid, presenting the appearance, at any rate, that information is absorbed through the skin and transmitted directly to the central nervous system. This under-narrated but visually arresting practice tends to suggest that clones are (ineluctably) part of a living informational network. But if that is the case, the network is not designed for transparency or translatability across its varied archives and operational fields. This emerges as a salient dimension of cylon life in season 3, when we discover that key command and control functions on board the cylon base ships (including navigation) are assigned to a “hybrid,” a liminal entity who represents a kind of evolutionary half-way point between the centurions and the models. Although her humanoid body resembles that of an evolved model, she is not mobile, but sits immersed in a tub of fluid, a self-aware program (or a consciousness—it is not entirely clear what her “hybrid” status entails) running a series of projections that are fundamentally inaccessible and incomprehensible to anyone else (figure 4.1). (Her body is female and the other cylons use the gendered pronoun to refer to her, although the hybrid appears to have no personality, gendered or otherwise.) In this state, she emits long, continuous streams of language in the utterly uninflected, leaden tone of a psychotic. When Balter is first brought into the hybrid’s chamber, for example, she stares vacantly ahead and intones:

Two protons expelled at each coupling site creates the motor force the unreal becomes a fish that we don’t enter till daylight we’re here to experience evolve the little toe atrophied don’t ask me how I’ll be dead in a 1,000 light years thank you thank you genesis turns to it source reduction occurs stepwise though the essence is all one end of line FDL system check diagnostic functions within parameters repeats the harlequin the agony exquisite the colors run the path of ashes. (“Torn,” 2006, Season 3)

The models are divided on how—or indeed, whether—to attempt to understand the hybrid’s speech, as a Six explains to Baltar, reeling from this first encounter:

Six: Most cylons think the conscious mind of the hybrid has simply gone mad and the vocalizations we hear are meaningless.

Baltar: But not everyone thinks that . . . ?

Six: The ones you know as Leobon believe that every word out of her mouth means something—that god literally speaks to us through her.

Baltar: She sort of controls the base ship, doesn’t she?

Six: She is the base ship, in a very real sense.

Baltar: My god!

Six: She experiences life very differently than we do, Gaius. She swims in the heavens, laughs at stars, breathes in cosmic dust. Leobon is right, maybe she does see god . . . (“Torn,” 2006, Season 3)

For the Leobens, the hybrid is an oracle, transmitter of a timeless divine awareness, which unfolds slowly and incompletely within the linear operations of language. “You can’t hurry her [the hybrid],” Leoben explains to the Galactica pilot, Kara. “You have to absorb her words, allow them to caress your associative mind. Don’t expect the fate of two great races to be delivered instantly” (“Faith,” 2008, Season 4). The Cavils, meanwhile, heatedly reject the idea that the hybrid’s speech is indicative of any consciousness or (un)reality other than the hybrid’s own. “The hybrid is always telling us something,” a Cavil says in exasperated reply to a Six and an Eight pressing him to heed and decipher her meaning. “They’re supposed to maintain operations on the ship, not vomit metaphysics” (“Six of One,” 2008, Season 4).

Whether the “conscious mind of the hybrid” is “mad” or works as the conduit for cosmic truths to which language is always inadequate matters less than the startling fact of her functional autonomy. The interesting point is that the clones can only speculate about the condition of the entity that “is the base ship”—in other words, the entity that is the material space they inhabit, the propulsion system by which they travel, and the network through which they communicate. The hybrid is not operated by the clones, nor does she respond to their commands. When a hybrid begins randomly “jumping” the base ship to new coordinates (the hyperspace “jump” is the series’ version of faster-than-light travel), an Eight explains to a baffled Roslin (who is visiting on the base ship) that this hybrid is distressed by the murder of a visiting Six aboard Galactica:

Eight: That’s why the hybrid’s panicking.

Roslin: Can you calm her down, tell her to jump back?

Eight: It doesn’t work like that. She makes her own decisions. And we can’t unplug her now because she’s wired herself into life support. (“The Hub,” 2008, Season 4, my emphasis).

What it would mean to “unplug” the hybrid who “is the base ship in a very real sense” is not obvious. In any case, the fact that the clones cannot manage the hybrid except by taking her off-line underscores that she is not an instrument, but an agent. Or more accurately, perhaps an agency—since her capacity for both affect and decisions does not seem bound to any structures of (in)dividuated subjectivity. If we attempt to “read” the hybrid within that framework, she can appear only as psychotic—a “personality” diffused and dissolved in a world of her own making. Unlike Hal 2,000 and its myriad science fictional successors, the hybrid is not a rogue machine that has slipped the bonds of its programming, an instrument that has eluded control, but rather a “hybrid” agency designed to animate an operational system that is not reducible to the intentions of its users. More exactly, perhaps, the hybrid is the rogue sentience recoded—the bitter machine who wrests control from human users recast as the fretful mind(er) of a system that its users can (no longer) apprehend in its entirety. The hybrid is the face of complexity, in other words, a figure for a field of operational protocols and informational flows that has grown too dense and rhizomatic to be mapped, demystified, laid bare.

Despite its highly networked character, then, cylon society is no more operationally integrated than it is culturally “uniform” or politically organic. From this vantage, it tends to appear that there are no discernibly cylon forms of culture and sociality at all—no authenticating values; no reproducible norms; no foundational institutions; and no coherent organization of command and control functions, which are routed through a psychotic cyborg (who may or may not speak to god). Yet the cylons are not simply cyphers, and the interest of the series lies precisely in its attempt to intuit emergent practices of power and sociality not constituted by the reproduction of interiorities. The models have not attempted (and failed) to establish a set of normative assumptions for the clones to cathect; on the contrary, they take for granted the flows and eddies of mobile intellectual energy and affect that are not bound in advance to the affirmation of any particular vision of the possible and the real. As Leobon notes to Galactica’s commander in the inaugural episode, “We [cylons] feel more than you can ever conceive” (Initial Miniseries, 2004). Leoben’s assertion is suggestively ambiguous: Does he mean that cylons have more capacity for feeling than humans attribute to mere “toasters,” that cylons are not unfeeling, in other words? Or does he mean that cylons’ capacity for feeling outstrips that of their human makers? Taken as a whole, I would argue, the series presses the second interpretation, yet understood this way, Leoben’s remark seems strangely quantitative. After all, we imagine, it is the quality of feeling that defines the feeling subject, as well as the particular people, entities, or ideas to which her feelings attach. Leoben’s point is simply that cylons feel more—and in this passing, rather cryptic comment he previews what will emerge as the defining quality of cylon sociality: namely, its intensities. The leaders of the human diaspora move to rescue and preserve a normative cultural content that sutures human affect to particular collective aims and objects. Along the way, they combat the cynicism, disaffection, and sometimes rage born of this disciplinary venture and the inevitable gap between the promise of belonging in which it traffics and the unequal allocation of prospects for living that it can never sufficiently dissemble. By contrast, the cylon models are disposed to feel more. The specific aims and objects in which they invest seem oddly random and exchangeable—one aspiration readily set aside for another. Why do the cylons decide to seek Earth together with the human survivors? Why do they first intern the humans on New Caprica? Why does Caprica remain devoted to Baltar despite his infidelities, lies, and rampant narcissism, which she herself details with unerring analytic precision? Why is Leoben obsessed with the Galactica pilot, Kara Thrace? One might argue, of course, that the thinness of cylon motivations is the evidence of bad writing and inadequate narrative development. But the cylon proclivity for mutable and routinely inexplicable enthusiasms is perfectly consistent. (If there is an exception that proves the rule, it is D’Anna’s ambition to reveal the final five and resolve the mystery of the models’ origins—quite possibly the only cylon objective that makes any real sense, precisely because the search for an anchoring cultural ground, as Cavil and the others rather brutally remind her, is not a cylon preoccupation at all.) Rather than attachment to fixed aims and objects, cylon society requires only the clones’ heightened fixations on whatever it is.

This is what the shift from discipline to control, from normative culture to proliferating managed difference, from individuality to simulacral personhood, from authenticated social order to derealized social space comes to mean in the series’ representation of cylon life: the aim or object of attachment (for dividuals and collectives alike) is incidental, because neither the aim nor object is meant to be realized (that is to say, secured, verified, normalized). What matters—what is socially significant and functional—is the magnitude of the attachment, its intensity; mania is the signature cylon affect. Nowhere is the value of fixation for its own sake, severed from the properties of the cathected thing, more brilliantly developed and explored than in the episode of carceral domesticity Leoben arranges for Kara on the planet New Caprica. While the rest of the human settlers are corralled in a muddy tent camp under cylon military control, Kara is taken to a sleek apartment, which Leoben has constructed as a kind of lovers’ retreat. The scenario is curiously reminiscent of the marriage mime that the slaveholder uses to seduce the slave in narratives and fictions such as Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and Clotel. In this antebellum set piece of perverted intimacy, the master promises to establish his fair-skinned chattel as his “bride” in a neat, secluded cabin in the woods, where she can cultivate her domestic felicity, freed from the hardships and indignities of field labor. As the undeceived slave woman invariably perceives, the mime is a lure, an attempt to recode rape as mutuality and coercion as consent. Indeed, from Kara’s perspective, the comparison is apt, and she responds, exactly like the romanced slave, with contempt and murderous rage:

Leobon: Hi, honey. I’m home. You kill me. I download. I come back, we start over. Five times now. [The corpse of his previous embodiment still lies on the floor.] I’m trying to help you, Kara. It’s why god sent me to you. Why god wants us to be together.

Kara: You’re right. I hear you, I do. So thank you for . . . putting up with me.

Leobon: Put it down, Kara. [She drops a concealed knife.] I’m a patient man.

Kara: You’re not a man.

Kara: I don’t need more frakking time.

Leobon: Of course it will happen. You’re going to hold me in your arms.

Kara: You’re insane.

Leobon: The face of god is no madness. I’m going to bed. Join me. [Gestures towards corpse.] Either way, you’re spending the night with me. I do love you, Kara Thrace. [Exits]

Kara [pounding on barred door]: Let me out! (“Occupation,” 2006, Season 3)

What terrifies in this scenario is not, or not so much, the “or else”—the threat of force that underwrites the courstship, the consequences of the suitor losing patience with the recalcitrant object—but rather the extent to which the very distinction between mimicry and authentic feeling fails to signify for Leoben. Kara’s repeated murders of Leoben insist on the difference, performing her absence of desire, or even simple tolerance, and her fury at being conscripted to his unreality. But no quantity of corpses accumulated in their living space seems sufficient to break down Leoben’s manic professions of love and devotion, precisely because they are not the fantasy construction of a real relation, which Kara’s rejection would thus expose as a vicious fiction (see figure 4.2). Rather, Leoben’s romance is a projection on the order of Caprica’s forest hallway, and like the hallway, its value is not of a function of its authenticity, but of the aesthetic satisfactions and affective intensities it sustains. It is not that Kara herself does not matter to Leoben’s scenario—that she disappears as a subject of his narrative. That is far more true of the slaveholder’s coercive romance, where the captive woman either produces herself in the image of the compliant “bride” or (and) reverts to the status of disposable human property. Here it is not the case that Kara’s resistance meets with violence—after all, it is Leoben’s corpses that pile up on the carpet—but that there is no impeaching the authority of the simulation. In the end, the episode lingers weirdly and disturbingly on the edge between terror and comedy, as Kara’s refusals and Leoben’s deaths reduce to mere incidents in a simulated domesticity that will not fail to “start over.”

In the face of Kara’s murderousness, Leoben produces a child—their child, or so he claims, conceived in vitro from eggs furtively removed from Kara during her earlier, brief captivity on a cylon breeding “farm.” (Although that earlier episode suggests the existence of an organized cylon program for human-cylon reproduction, this narrative thread subsequently disappears, perhaps in order to preserve Hera’s uniqueness, though the effect is to present assisted reproduction as another passing cylon fixation.) Leoben’s ploy could hardly be cruder:

Leobon [leading the child into the room]: I’ve seen her path. Difficult but rewarding. She’ll know the mind of god in this lifetime. She’ll see patterns others do not see. She probably gets this spiritual clarity from me. She’ll be hungry soon. There’s food on the table. You won’t let your own child starve. (“Precipice,” 2006, Season 3)

Kara remains at first implacable, refusing to acknowledge the little girl, much less see to her needs. But when the neglected child falls and hits her head, Kara is overcome by guilt and suddenly comes to believe that the child is in fact her own. As she and Leoben watch over Casey’s bed, we see her hand seek out and clasp his. For Kara, then, the child represents the Child, who therefore serves to authenticate and actualize what she has, up until that point, rejected as a coercive pretense. The child turns out to have been borrowed for the occasion, and in the chaos of liberation, a shocked Kara surrenders her to the tearful woman who recognizes her missing daughter in Kara’s arms.

But it is not clear that Leoben’s deceitful procurement of a daughter exposes his devotional rhetoric as fraudulent or otherwise gives the lie to his claims of “spiritual clarity.” After all, Leoben has no need to invoke god’s will so as to reconcile his pursuit of Kara with cylon social norms. Conversely, there is no way to impugn the clarity of his spiritual insights by marking their distance from the values that religion purports to uphold. Simply put, Leoben’s faith is not the cover story for sexual coercion and kidnapping, and in turn, the evidence of his manipulations does not unravel his professions of faith. Rather, as this episode underscores, there is no metric of failure in this form of religion, because it is not a system of disciplining behavior, but one of modulating intensities. The cylon monotheist is not a fallen being. She does not seek to earn her place among the lambs through good works, nor is she compelled to read the narrative of her experience for the signs of her election. There is nothing blasphemous in Leoben’s claim to gaze upon “the face of god,” because there is no (longer a) discontinuity of scale between divine intent and (humans’ or) cylons’ intuition of that intent. Faith aligns with zeal, but never with guilt, or self-loathing. In this theological scenario, then, the pilgrim’s path to faith is no longer seeded with doubt. When Baltar rails against Head Six for inciting him to run for the presidency and to risk the “public humiliation” of heightened scrutiny and possible defeat, she cautions him sharply not to “blaspheme.” Baltar’s doubt in her correct interpretation of god’s plan earns him a pointed reproof—but doubt is also the only thing, or so it seems, that imperils his salvation. Sin becomes strangely inconsequential, or simply illegible. The cylons repeatedly cite a reverence for life, which, they argue, distinguishes them from humans, notwithstanding that their arrival on the scene of the narrative is marked by their genocidal assault on humanity. Their posture seems less self-serving than simply dissociative: the contradiction between a reverence for life and unleashing a nuclear holocaust does not need to be explained, much less expiated, because the sanctity of life is not a legitimating social principle. The cylons can revere god by respecting life—and yet their reverence does not preclude genocide, because faith is an affective disposition, and not a disciplinary norm.

Of course, mania is always bound to depression, however long deferred. Cylons live without guilt, but not without grief. D’Anna (eventually un-boxed) succeeds in her quest to reveal the five, but falls into despair when Earth turns out be a contaminated ruin, incapable of harboring life. As the human-cylon landing party prepares to evacuate the planet, she tells Tigh (Adama’s second in command, eventually revealed to be one of the original cylons): “I’m not going. This will just keep happening over and over again. I’m getting off this merry-go-round. I’m going to die here with the bones of my ancestors. Beats the hell out of being out there with Cavil” (“Sometimes a Great Notion,” 2009, Season 4). And when Kara, searching near the ruins of the shattered city, finds her crashed fighter plane with her own corpse inside, Leoben’s ecstatic faith in Kara’s divine destiny seems all of a sudden to dissolve. “If that’s me lying there, then what am I?” Kara screams, as Leoben retreats from the scene in mute defeat (“Sometimes a Great Notion,” 2009, Season 4). Having voted against her line, Boomer is horrified when Cavil double-crosses the Sixes and Eights, by jumping the “resurrection ship” away from the cylon fleet and then attacking them. “But we’re killing them. I mean, we’re truly killing them, my own sisters,” she remonstrates (“The Ties that Bind,” 2008, Season 4). But it is not clear that she avows her own complicity, and in any case her anguish turns to simple numbness. When one of the five “creators” celebrates cylon creativity, compassion, and ability to love, Boomer responds quietly: “Love? Who? Humans? Why would I want to do that? Who would I want to love?” (“No Exit,” 2009, Season 4). The cultivated intensities of cylon affective life yield periodically, if not ultimately, to the psychic flat-lining of the depressive.

Futurology

It is tempting to try and draw out more sharply and explicitly the proximity of cylon culture, politics, and sociality to “our” own historical present, in and beyond the United States. To this end, I might discuss proliferating practices of self-mediation (such as emailing, blogging, tweeting, social networking) that tend to produce identity as a quantity of uploadable data, or mobile technologies (iPods, smart phones, laptops, and the like) that dismantle public space, turning sites of anonymous collectivity into so many “dividual” interfaces. I might cite the workings of complex systems that seem no longer sufficiently determined by the inputs of their users, such as the current financial markets, or discuss the manic quality of much contemporary faith, where the production of affect seems increasingly disconnected from the production of moral obligation. I could invoke the turn from depth psychology centered on the always guilty bourgeois subject to discourses of self-care oriented to the management of stress and depression. I could say more about the current dismantling of modern political institutions: about the end of the rule of law and the reduction of law to a mere tactic; about the decomposition of the body politic and the reconceptualization of the popular as a field of proliferating, managed political differences; about the erosion of popular sovereignty and the increasingly simulacral quality of electoral politics. And last but assuredly not least, I might discuss the ways in which so many of these transformations articulate to changes in the production of time and, especially, futurity—articulate, that is, to processes of speed-up that compress the boom and bust cycles of capital to years and months (rather than decades) and to forms of governmentality predicated on tactical flexibility, rather than the continuity of founding institutions over time. In part, I omit this effort here because I follow these lines of reflection in other chapters. But more fundamentally, I want to insist that the value of allegory lies in the slippages, not the equivalencies. Allegory gravitates thematically to violence, crisis, the dissolution of decaying orders, as I began by noting—but it does so (and this, too, is Benjamin’s point) because its formal structure reiterates the violence. To allegorize history is to break it apart, to ruin it, so as to tell it otherwise, to reassemble the pieces in overwrought form—paradigmatically, for Benjamin, the form of the baroque. The value of allegory, then, lies precisely in the ways it turns us out of contemporary contexts, along pathways that are never simply retraceable.

So my aspiration is not to corral the disparate elements of the series’ narrative and highlight their relevance to the contexts of U.S. political culture today, but rather to appreciate the alterity of the allegorical scene and to consider what we might perceive there in relief. In particular, I would argue, what shows on the terrain of an imagined cylon society is the degree to which the repertoire of modern emancipatory politics (its critical gestures, its temporalities) has become a set of functional elements within the structures and agencies of control. In other words, the prospects for and possibilities of insurgent imaginaries and insurgent practice change fundamentally when power no longer exerts itself by securing the reality in which its reproduction is given, or as Edelman puts it, more subtly, in which its reproduction has already taken place, at the moment we commit to “the children” and the form of the world to be passed on. In this novel framework, the political force of the break—the rejection of conventional attachments, the rescinding of belief in the capacity of established norms and institutions to deliver the future that authenticates the present—becomes newly serviceable as a tactic of control in a political field where, it seems, there are only tactics in an ongoing war of position. Theoretically, of course, the revolutionary break would mark the arrival of an opposition into a full-fledged war of maneuver. Yet this understanding assumes precisely that the established power is staked on its ongoing capacity to realize the present by instituting the future. The revolution breaks with this instituted future and so shatters the present; on the ruined ground of the disestablished order, it moves to institute a new beginning. But in the cylon present that is and is not quite our own, the power of realization is not (any longer) the name of the game. Power is transacted in and across a field of simulations, or projections. It is about the production and modulation of intensities to whatever unilateral ends. It knows, indeed, it triumphs in the knowledge, that futurity never arrives, not as such, that we are always consigned to the present. The future stands for nothing—and so for everything, flexibly. The future is finding our own destiny (cylon ethnonationalism). The future is militarized cylon rule of humans. The future is human-cylon cooperation in the search for Earth. The future is human-cylon breeding farms. The future is human-cylon love. The future secures nothing in a world of proliferating simulacra. The iconic child is brought over from elsewhere—a quaint, affecting figure who elicits a magnitude of feeling for a time. And in the already shattered reality of this present, there is nothing besides the serialized starting over, which changes nothing.

Simply put, in the cylon present that is and is not quite ours, systemic power operates, not by norming political belief (“what will count as political discourse”), but by the unleashing and management of enthusiasms. It is crucial that the series does not narrate this as conspiracy. The cylon masses have not been duped, distracted from the real scenes of political decision-making by a cynical oligarchy. Those who control or aspire to control operate on the same derealized terrain as the dividuals on whom they impose. Leoben may manipulate Kara’s feelings by producing a fictitious child, but he is and remains fully in the grip of his own obsessions. If this is a hallucinatory politics, there is no one who isn’t tripping—least of all, those who stand to gain. This hallucinatory politics is not, of course, a politics that fails to act on the world; it is rather a politics where the real effects it unleashes (the ruined ecosystems, the body counts, the diasporas, the internments, the stolen lives) need not be reconciled to a coherent construction of the present or a survivable future. In this way, it is a politics that appears to preempt the ground of our opposition. How do you break with a simulation, except, perhaps, by recourse to the very foundationalist terms, such as verifiable truth and authentic feeling, which critique is primed to view with suspicion? The merit of the allegory is to pose the problem that we barely know how to think, much less resolve—the problem, that is, of the Left in an already derealized political field.