EPILOGUE

SOMEWHERE

PERCEPTIONS, PROCEDURES, tastes, customs, movies, politics, people. They all change. It is impossible to confront West Side Story as people did in 1961, when they excitedly clipped the order blank from their newspapers to send away for tickets, then waited weeks and months to see if it could live up to the reports, the reviews, the word of mouth. For nearly all of them, it did so, and they eagerly passed the word along and even went back to see it again. All of that is in the past, along with so much else that seemed to matter when West Side Story was first playing in theaters. So much about it must be seen differently now—and yet nothing keeps it from asserting its importance, worth, and permanence.

Unquestionably, the show that gave birth to the film is a work of lasting greatness, extraordinary in both its quality and its relevance. Some have said that it far outdoes the movie in that regard, but is that really the case? Theater often views cinema with disdain, so look again at the film. Are there moments of greatness that are any less worthy than on the stage? Are the finest parts of the movie anything less than indelible? Some may say “yes,” while for many others the answers to these questions are all “no.” If it was the product of a medium that can be crass and irrelevant, it was blessed to be the creation of people whose skills, intentions, aspirations, and sincerity were vastly above the norm. Between the mastery of Jerome Robbins, the unwavering expertise and craft of Robert Wise, and the dedication of its cast, musicians, artists, staff, and technicians, its possibilities were realized to an unprecedented degree. For all its long and complicated creative process, there was a final outcome that justified everything.

Obviously, we cannot see West Side Story through those same “I’ve heard about it, now stun me!” eyes people had in 1961. Nevertheless, there are moments that are so arresting, so exceptional or inimitable, that they give a clue to the initial excitement people felt when they saw it. Everyone has notions regarding the film’s special and unique moments, those things not found in any other movie, nor in any other production of West Side Story. They belong only here, and everyone who cares about this film has her or his own list. What follows, then, is a sampling.

⋆ The three-note whistle. It’s the first sound heard in the film, before the overture. Then, even more eerily, it’s heard again with that bracing aerial shot of the George Washington Bridge. Even for those who don’t know West Side Story, it seems to portend that this may not end happily.

⋆ The uneasy thrill of the overhead zoom down to the Jets in the playground, which cuts to the arresting first view of Russ Tamblyn in profile, accompanied by that finger snap.

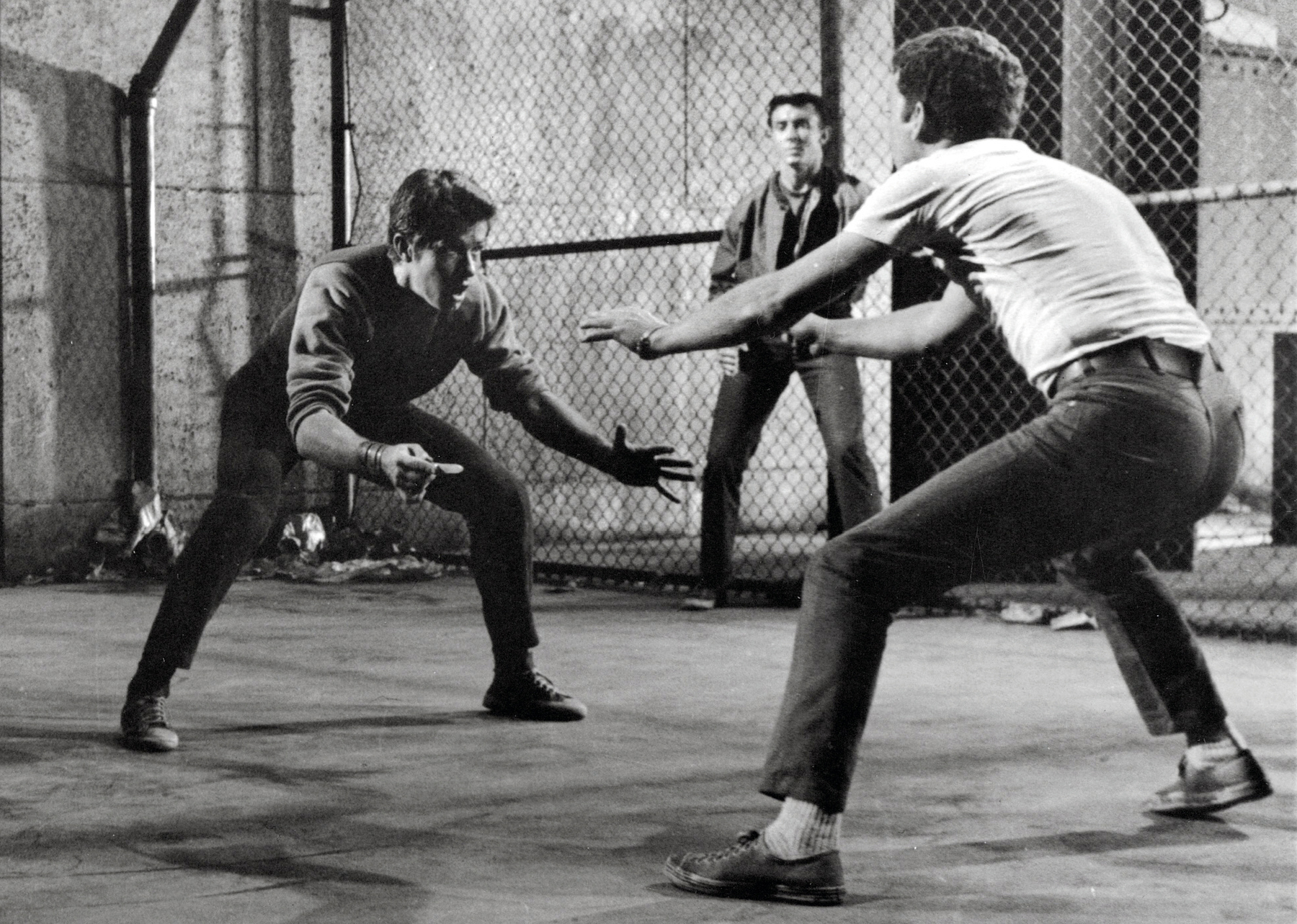

⋆ George Chakiris, flanked by Jay Norman and Eddie Verso, dancing in the Prologue, as photographed from a low angle that frames the trio against a row of tenements. The shot of them with left legs extended high became iconic, and no wonder.

⋆ The recurring motif of doors. If the fire escapes offer hope, perhaps those endless lines of doors in the Prologue (and elsewhere, including the final credits) signify something more ominous. No way out, perhaps. In a far different vein are the multicolored glass panes in the doors to Maria’s bedroom. Do they serve as the portal to the bright world shared only by Tony and Maria? Whatever they are, they’re unforgettable.

⋆ Carole D’Andrea as Velma, with her odd and mesmerizing combination of the ethereal and the tough, the detached and the engaged, as seen first in the gym dance and then, later, during “Cool.”

⋆ The hypnotic moment, both theatrical and cinematic, when the other dancers, and then the walls, melt away as Maria and Tony see each other for the first time.

⋆ Yvonne Othon, as Consuelo, during the verse before “America.” Reacting to Rita Moreno’s “I love the isle of Manhattan,” she exclaims an ad-libbed “I know you do!” in flawless “Nuyorican.”

⋆ The banter and rapport, snappy, affectionate, and knowing, between George Chakiris and Rita Moreno in “America.”

⋆ The dreamy close-up of Natalie Wood in “Tonight,” when Jim Bryant sings “Today, all day I had the feeling.”

⋆ The vaudeville-style banter of “Gee, Officer Krupke.” For some, it belongs in another, more traditional show, but just listen to those abrasive, sardonic lyrics.

⋆ The offhand delight, during “I Feel Pretty,” of Yvonne Othon chewing gum and singing backup at the same time.

⋆ The extreme and even shocking cut, visual and aural, from the beatific “One Hand, One Heart” to the blaring and blazing start of the “Tonight Quintet.”

⋆ The editing of the “Tonight Quintet,” which becomes faster, more percussive and virtuosic, as the sequence progresses. The number has been rethought so effectively that most later productions have found it necessary to draw from it.

⋆ The expression on Russ Tamblyn’s face when Riff realizes that the Rumble has gotten “real,” quickly followed by that famous first flash of the switchblade.

⋆ The “Cool it, A-Rab” moment in the garage, with David Winters giving an unflinching demonstration of gang-member instability. The wonder of “Cool,” in fact, is that the whole of it is pretty much up to that level.

⋆ The fury, pain, and conviction that inform Rita Moreno’s “Don’t you touch me!” The entire scene has been so painful to watch that it needed this strong passage to move it to the devastating conclusion of “He shot her!”

⋆ Natalie Wood in the final scene, snarling the word “trigger” and crying out “I can kill, too,” with blazing eyes. Then, the dignity of her exit, a solitary figure in red and black.

⋆ The conclusion of the final credits, with the camera tilting upward to the first word of the sign “END OF STREET.” Robert Wise had done something similar in his previous film, Odds Against Tomorrow. There, the sign read, “STOP DEAD END.” This one seems even more final.

The very last strains of “Somewhere,” which end the film as they did the show, have a haunting and haunted quality that is deeply felt but not at all conclusive. As a corpse is carried out, followed by a “widow” and mourners, the music lingers without finding resolution, refusing to bring a tidy end to what has come before. Leonard Bernstein’s daughter Jamie, reflecting on that passage, remarked on the sad and inevitable truths carried by these bars of music. “So that’s how West Side Story ends,” she says. “Or is the world getting better? Is there hope for us to find a better place to all live together in harmony? Hmmmmm… not sure.”

No, the show’s creators couldn’t be sure about there being hope. Nor could the filmmakers. Both on stage and in extra-wide Panavision 70, West Side Story wants to reach toward hope, but reality keeps pulling it back. That back-and-forth struggle has been expressed through some of the most resourceful songs ever written for a musical, some of most innovative and character-driven choreography of all time, and, on film, a dedication to the craft that goes far beyond the aspirations of most musicals. Up to and including those final notes, the artists and filmmakers have been honest—in a musical, yet—to a degree that could not be approached by most people who make movies. Indeed, one of the everlasting beauties of West Side Story is that it doesn’t suddenly turn false at the end, promising a solution where none can be found. It’s tragic and heart-rending yet also clear-eyed, and by doing this it stays true to itself and respectful of its audience. This is the kind of achievement that is possible when people believe in what they’re doing and in the film they’re making. With this degree of integrity, and with all the care, artistry, and feeling available to them, they made a monument that will continue to endure. For six decades and counting, this movie has not grown dim or become less captivating. Nor has it passed away. “Even death won’t part us now,” Tony and Maria sing. They’re completely right.