PROLOGUE

COULD BE…

ALL IT TAKES IS THOSE FINGER snaps. As soon as we hear them, we’re there, we’re committed, we’re riveted. Even before the gang members begin to dance, before Maria and Tony meet, before “Tonight” or “America” or “I Feel Pretty,” we’ve been drawn in. It’s always that way with West Side Story. From its premiere in 1961 up to now, it has moved beyond ordinary limits of cinema. It has become lodged in our memories and hearts and after six decades, with stage productions, endless homages and parodies, and even with a remake, it continues to hypnotize audiences in a way few works do. Its excitement, its music, romance, and tragedy—even the parts so raw that they can be difficult to watch—none of it can be compared with any other film. Shockingly enough, it’s perhaps more relevant now than when it was new, with conflicts still being played out in the world in many painful ways. Few movies are anywhere as overwhelming as this one, especially when it is seen on a massive screen, as its creators intended. For those creators, the complications of making it were, on a steady basis, all but unimaginable. Fortunately, the rewards of their hard work are all remarkably apparent. From the breathless and bracing overture all the way to the stunningly imaginative credits at the end, the momentum never lets up. Corny? Not a chance. As one of its characters sings, it’s “cool,” everlastingly so. And, with its dance, music, and use of Manhattan locations, also hot.

Unlike nearly every movie made from a musical show, West Side Story is unique: in spite of its high-profile source, it has thrived on its own. Where a South Pacific (1958) or a My Fair Lady (1964) will eternally be “the film of the show,” West Side Story stands on its inherent merit and impact as well as that of its material. It is because of that impact that the songs became standards, and that the show’s subsequent popularity has remained so constant. It’s due to the film, really, that so much of West Side Story lives permanently in our minds: the sight of tough guys dancing down the street, the use of fire escapes to evoke romantic longing, the depiction of time literally standing still when two lovers meet for the first time, the notion that two battling street gangs can assume the dimensions of classical tragedy.

In the theater, West Side Story had been completely without precedent, breaking new ground in subject matter, unity of music and dance, overall presentation, and seriousness of intent. Leonard Bernstein’s music, alternately lyrical and jagged, was uniquely coupled with Stephen Sondheim’s bright lyrics and the Romeo and Juliet–inspired plot, with its Us-versus-Them ethnic clash that was both pertinent and prophetic. The script, by Arthur Laurents, was lean and powerful. Most of all, there was Jerome Robbins, whose choreography and direction, whose sheer vision, were of a caliber not previously seen. The result was electrifying, yet so theatrical that it could not be put on the screen verbatim. It was left to the movie’s producer and codirector, Robert Wise, to grasp that a film version would need to stake out entirely new ground. It could not be a copy of the show, nor could it be like anything else that came before. And it wasn’t.

As a film, West Side Story accomplished monumental feats. It ran literally for years, so pervasive and inescapable that, at the time, it was next to impossible to go to a store and not see the soundtrack album (on LP, of course) or the paperback novelization, reprinted nearly in perpetuity. Both the soundtrack and the book sported that distinctive, indelible logo with the fire escape and red background that evoke the film so effortlessly. Its influence goes well beyond that of a conventional film hit, past even the generations of young people it has inspired to become dancers or become involved in musical theater. Its unflinching portrayal of prejudice and hostility has heightened an awareness of cultural inequities and societal conflicts and, in doing so, has delivered messages of brother- and sisterhood, peace, and healing. In the realm of popular entertainment, such achievements and messages are incredibly rare. In a much lighter vein, and not surprising with a work this pervasive, it has inspired jokes and homages so numerous they are impossible to count. Even animated TV series such as Family Guy and Animaniacs have gotten in on the act. (The latter show was executive-produced by Steven Spielberg.) Yet it’s the original that stays eternal and even fresh. Like that legendary one-woman tribute Cher paid to it when she played all the lead roles in a 1978 television special, West Side Story remains a stand-alone accomplishment, glorious and irreplaceable.

Being a movie musical, West Side Story falls into the grand procession of influential works that begins in 1929 with that creaky pioneer The Broadway Melody, continues through 42nd Street (1933) and the Astaire-Rogers films in the 1930s, and moves on to The Wizard of Oz (1939), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), Singin’ in the Rain (1952), and others, later to The Sound of Music (1965), Cabaret (1972), and all the way up to La La Land (2016). It equals these in significance, but it could not be more different in tone and overall direction. It’s not that West Side Story is so much better than, say, Top Hat (1935) or Singin’ in the Rain, because in the estimations of many it’s not. What it is, incontestably, is different: in its goals and ambitions, its methods and intentions, its effects and impressions. This is made clear in the very first minutes, with that bravura overture playing over abstract designs that finally dissolve into a Manhattan skyline. This is obviously a film that sees itself as a major work. Neither pompous nor self-satisfied, yet always aware that it is striving for quality and meaning outside and beyond conventional boundaries of musical theater or film.

“Epic” and “musical” are two words generally not found in each other’s company, but what is West Side Story if not a musical epic? In its themes and presentation, it takes a big approach, not unlike other blockbuster movies of its time like Spartacus (1960) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). While it doesn’t slight the details, it is definitely a film that sets out to be big in scale, attitude, and intent. While most find this monumentality to be effective, others (including film critic Pauline Kael) have found it off-putting. Movie musicals do traditionally divide audiences, and West Side Story is no exception. Yet, as one of the most loved of all musicals, it came by its stature honestly and, as a look at its creation makes clear, through all-but-unearthly amounts of rigor and effort.

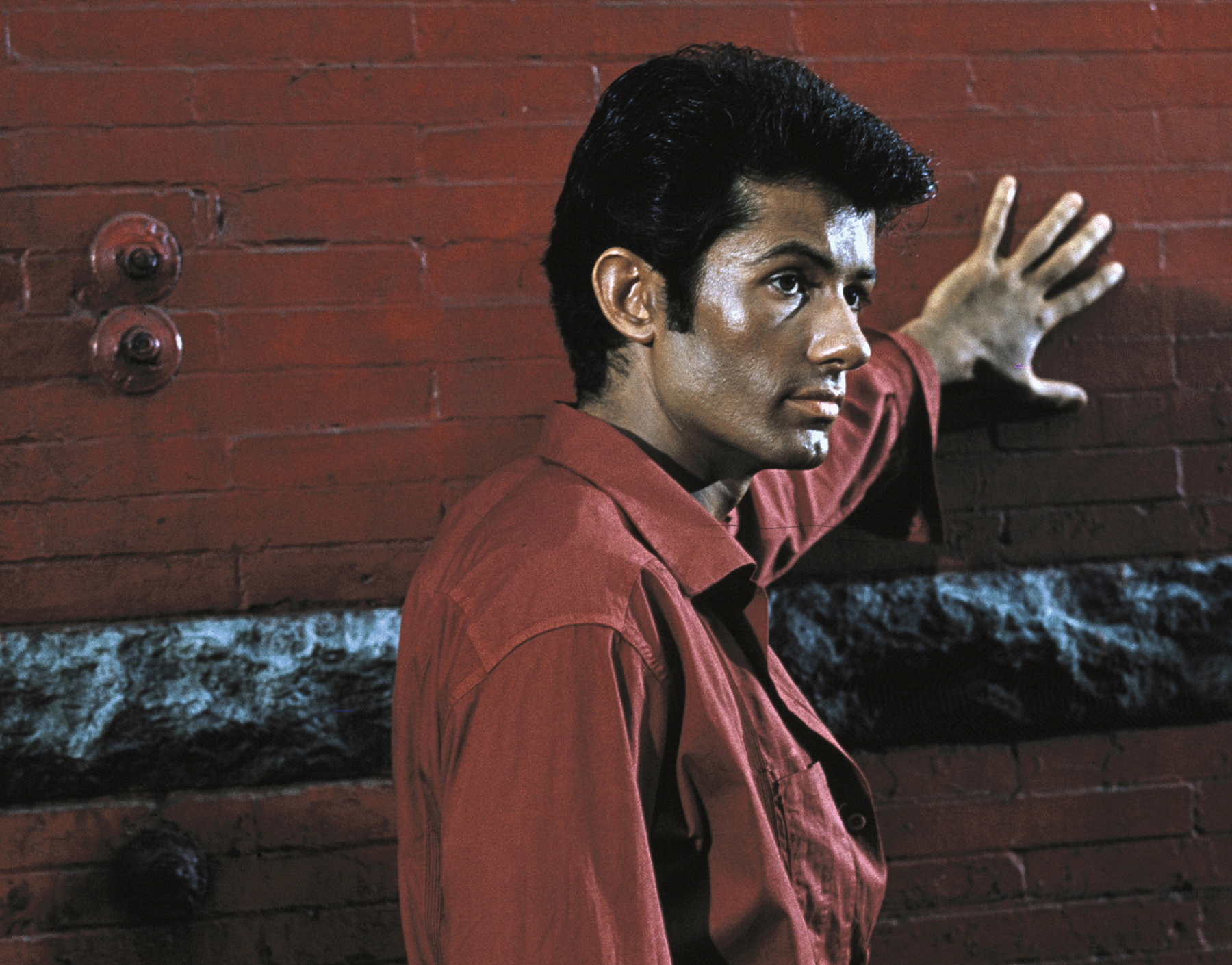

Mentioning West Side Story to people elicits the dawn of excitement in people’s faces. First in their eyes, then in their expression and in the finger snaps that sometimes follow. It goes further than simple recollection or nostalgia. The plain truth is that West Side Story has affected many people very deeply. Is it because of its neo–Romeo and Juliet romantic tragedy? That surely plays a role. So do the songs and those extraordinary dances full of verve, precision, and keen characterization. So, too, does Natalie Wood’s star charisma, Rita Moreno’s blazing conviction, Russ Tamblyn’s nervy athleticism, George Chakiris’s suave and vaguely sinister grace, and, for many, Richard Beymer’s first-love sincerity. Those dancers, too—those men and women of great ability working hard, totally into what they’re doing and completely intent on giving their best to Robbins, the camera, and the audience. All these factors matter intensely, as do the widely divergent gifts brought to the work by Wise and Robbins, and by all the artists and technicians working with them. On a production of this complexity, everyone’s contribution counts for a great deal.

Traditionally and understandably, much of the credit for the film’s success has gone to Robbins. To connect the dance and song with the subject matter took skill so nuanced and complex as to be almost inconceivable, and it is not uncommon, among those who worked with Robbins, to hear him referred to as a genius. His vision, which had made the show so compelling, was essential to the film, although—as will be recounted here—Hollywood and New York are far different places. One of the bottom-line verities of musical films is that they must work immensely hard to make the final result seem effortless and organic. Robbins was a perfectionist of the first order, which made for brilliant results while causing numerous delays and budget increases. As a result, one major theme in this saga concerns the eternal struggle between art and commerce. Think of it as a sort of behind-the-scenes version of the war between the Jets and the Sharks, playing out both on the streets of New York City and on Hollywood soundstages. The positive results of this conflict were plainly evident in the final product; those that were more negative were off the screen and, often, deeply felt. Both were responsible for the way West Side Story turned out.

Robbins’s codirector, Robert Wise, has seldom received anything like the recognition given to Robbins. Yet, in crucial ways, he had the greater responsibility and as significant an impact. As producer, his was the final word in selecting the cast and crew, for all the preparatory work not concerned with dance, and for the demanding job of assembling and polishing the final product. If often a quiet presence on the set—especially by comparison with the volcanic Robbins—he offered the most competent leadership imaginable, inspiring devotion from the crew and keeping an unwieldy project moving along as steadily as humanly possible. He was as necessary to West Side Story as Robbins, and surely the film turned out as successfully as it did in large part because it was directed by two men who were, in so many ways, polar opposites.

Richard Beymer and Natalie Wood

If Wise and Robbins were not always in accord, they were both aware that this was a wholly unconventional production, all the more so for its being made independently outside the confines of the major movie studios that still existed. With the intensive amount of preparation required, and the enormous amount of time involved, it was one of the most costly films shot in America up to that time. In all of it—conception, planning, casting, rehearsal, shooting—nothing came easily, nothing was taken for granted, nothing took less time, effort, or money than originally anticipated, and crisis often seemed to be a daily occurrence. When the triumph of acclaim and Oscars came, each person involved would have her or his own takeaways, and not always the expected or happy ones. Since then, there has been a legacy of glory and ongoing regard and, in later years, some controversy. All of this will continue even as, in 2020, the Steven Spielberg remake looms as both tribute and competition.

With a film this famous, this celebrated, loved, and complicated, there are many stories to tell in addition to the one about Tony and Maria and the Jets and the Sharks. There is first that of the work itself and, not surprisingly, much of the West Side Story literature tends to concentrate on the show. Generally, the movie is brought in as something of an inevitable afterthought. This does a disservice to both history and to the movie’s triumphs, so let it be stated again, as clearly and directly as that gang whistle at the beginning: the achievement and repercussions of this film are completely without parallel. It’s no overstatement to note that it forever changed the way people looked at musicals and at movies in general. The wonder is that many millions still find it every bit as thrilling as they always did, and the many who have come to it later on are usually startled to find out just how much it lives up to all the hype. Where else could there be found this blending of rough realism and delicate romance, of stark immediacy and timelessness, of cutting-edge theater and big-time cinema, of anger and comity, of anguish and exhilaration, of Shakespeare and today’s headlines? None of this, as will be recounted here, was achieved without great effort, nor without great talent.

The overture is now ending, and the title is coming up on the screen. It’s time for West Side Story.

The exhilaration of “America”: Maria Jimenez, Joanne Miya (hidden), Rita Moreno, Yvonne Othon, Suzie Kaye