Appendix A: The I Ching

There are many methods of divination in widespread use, from the trivial to the deeply searching. It makes sense that we should try to learn from those who have gone before us and look at practices that have stood the test of time. Among the latter are astrology, rune stones and the tarot. What such approaches have in common is that, somehow, they enable us to access deeper unconscious levels of our minds where we come into contact with knowledge or understanding that is not clear to us in our normal conscious state. Our ‘readings’, therefore, are to be understood as guidance about the real or inner nature of a situation and perhaps also about how it might unfold in the future. We must also remember that our interpretations may be somewhat biased by our conscious thoughts, our expectations and our desires.

The I Ching, or Book of Changes, is one of the oldest known such methods, developed over many centuries in a philosophically very advanced culture. For readers who may be unfamiliar with it, this is the briefest of introductions intended only to reassure you that it is quite easy to use (although understanding its results may be more demanding!). There are many other good books describing its philosophy as well as many new translations; finding one that suits a particular individual is a matter of patient experiment. However, the version to which I have been referring is still widely regarded as the most faithful to the original, even if it does require an appreciation of metaphor and symbolism and an indulgence towards some of its more archaic language...

The importance of proper preparation, and the formation of a proper question, cannot be overstated. Use of the I Ching is not a party trick. If we are seeking to access the inner stream of consciousness, we are not likely to be successful if our attitude is superficial: “Right then, when shall I win the lottery?” This is not to say that money, for example, is not important; but the purpose of this kind of divination is to understand the underlying patterns, cycles and energies of our lives. So a more appropriate question might be “How can I improve my material security?” The I Ching ‘responds’ when it is approached with a particular issue, formulated in terms of our life changes.

If the question is too vague, so will the answer be; but on the other hand, if we are too specific we may fail to recognise that the book might be telling us something deeper and more important. If I ask the question “How will my relationship with so-and-so develop?” I might receive an answer that is clearly relevant to this relationship, especially if it is an important one, or I might read some more general advice about my approach to emotional relationships, especially if so-and-so is in fact not that important. It is an extraordinary quality of this book that it answers the questions we should be asking rather than, sometimes, the ones we do. So before even picking up the book it is worthwhile giving very careful thought to the question we are going to ask; equally, having put the book down, we should give careful thought to what question has actually been answered!

So clearly it is essential to develop a calm and thoughtful state of mind when consulting the book, in effect just as if one were about to address a spiritual guru. The responses often make one feel that this is exactly what has occurred. A mind in chaos or emotional turmoil, seeking an instant solution, is not going to be properly receptive to any good advice (Hexagram 4, by the way, is the book’s way of telling the enquirer to go away and think about things more carefully!). So you should allow time for the consultation, at the very least thirty minutes, and ensure that you will not be disturbed. You will need pencil and paper to note the results as they occur. A sense of the occasion can be encouraged by some personal ritual, although this is a matter of individual preference. Personally, for example, I use candlelight and incense and focus my meditation on some religious objects that are meaningful for me, calming my thoughts and clarifying my question and its implications.

There are several methods used for carrying out the consultation. The most ancient and traditional one involves taking a bundle of 49 yarrow (or similar) sticks, then subdividing them in a certain way into piles and noting how many remain. This method has the advantage of being quite time-consuming and therefore in itself meditative - it helps one to focus on the process. However, I am not going to describe it here or even recommend it (any decent I Ching translation will give an explanation of it if you are interested), because on the one hand it is complicated and on the other hand I do not believe it gives fair results. The reasons for this will be given later.

Most people now adopt the ‘coin oracle’, which is easy to carry out (although some think its simplicity a disadvantage). Use three coins of the same type, perhaps Chinese, kept solely for this purpose: the tails or least decorated side is designated ‘yin’ (the feminine principle) and carries the numerical value 2, while the other side is designated ‘yang’ (masculine) and has the value 3. With the mind focused on your question, the coins are shaken between the hands and then cast together onto the table. The total of their values will be 6, 7, 8 or 9.

6 results from yin + yin + yin and represents a ‘moving yin’ line, drawn -x-. It is called ‘moving’ because it is entirely feminine and thus not in balance, so it must change.

7 results from yin + yin + yang in any order and represents a ‘yang’ line, ---. This is in balance and does not change.

8 results from yin + yang + yang in any order and represents a ‘yin’ line, - -.

9 results from yang + yang + yang and represents a ‘moving yang’ line, -o-.

You have now obtained the first, lowest, line of your reading; the procedure is repeated another five times to obtain a complete hexagram, or six-line figure, of which there are sixty-four possible (ignoring for the moment whether any lines are moving). There will be a page in your book telling you the number of your hexagram.

For example, you cast the coins six times and obtain 6, 7, 9, 8, 8, 7. Your hexagram is number 18:

There is a great deal to learn, if you are interested, about the procession of the hexagrams, their structure and inner meanings, but little of this is necessary to the actual reading. Each hexagram has a descriptive name and an introductory commentary describing the situation with which it is concerned; there is also a brief ‘judgement’ and, in most translations, an ‘image’ which describes the symbolism with which it is composed.

If you have not obtained any moving lines, the commentary is your answer: the situation is stable and the book’s words advise how to think about it. Usually, however, you will have one or two moving lines and it is the explanation of these that is the most significant part of your reading since they address specific issues in the situation and describe how they might change. Make notes on everything you have read so far that you think might be relevant to you and consider what you are being told - often it is surprisingly direct and the text will always include advice about the spiritual, or ‘superior’, way to approach a situation.

When you feel ready to move on - and this might be several hours later - consult the new hexagram that results when your moving lines change their nature i.e. a moving yin line becomes a yang line, and vice-versa. The commentary (only) of this new hexagram describes the potential outcome of the situation you have asked about, given that you heed the advice in the first part of your reading. The above example would change to hexagram number 41:

It may be helpful now to review the reading described on page 20 as an example.

It seems to me that any method of consulting the oracle must be genuinely random if its apparently meaningful results are to be taken seriously. That is, there must be a theoretically equal chance of each possible result. If this is so then a reading that is clearly appropriate to one’s question is all the more remarkable. Of course, some might argue that randomness doesn’t matter because the mind is in any case somehow influencing the outcome, perhaps by some sort of telekinesis. But on the one hand we just don’t know if this is so and on the other surely the mind will perform best on a level playing field.

When tossing coins there is an equal chance of heads and of tails. So the probability of a moving yin or of a moving yang line is 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 = 0.125 or 1/8th. For a yin or yang line it’s the same calculation except that there are three ways of obtaining each (e.g. yin + yin + yang, or yin + yang + yin, or yang + yin + yin) so the probabilities of these lines are each 0.375 or 3/8ths. Because these probabilities are equal, this method can be said to be genuinely random. We can also predict that on average one quarter of the lines obtained will be moving ones, which is a mean of 1.5 moving lines per hexagram. So it is normal to have one or two moving lines.

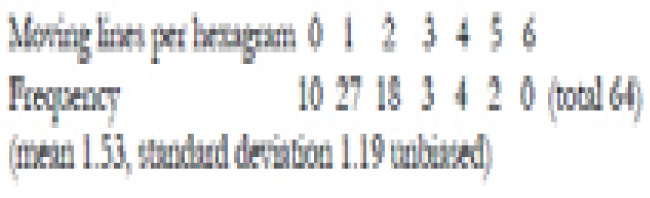

To check this, I reviewed sixty-four readings obtained over a period of just over four years. There was a total of 98 moving lines, an average of 1.53 per hexagram, almost exactly as expected. The numbers of moving yin and moving yang lines were, also as expected, nearly equal (47 and 51).

From the point of view of statistics there is nothing very unusual in this distribution, showing that the method is fair. However, I also checked how many times each individual hexagram occurred, either as a first answer or as a result:

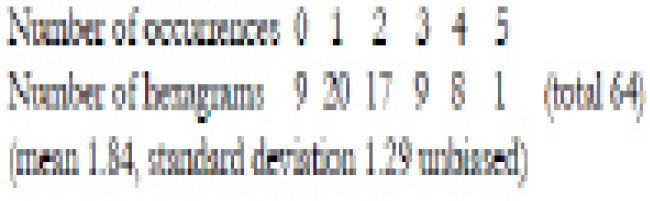

Of sixty-four readings, ten had no moving lines and the rest yielded a second hexagram as a result; thus one hundred and eighteen hexagrams were obtained altogether making the average just less than two per reading. If an I Ching reading were simply a random exercise, this second distribution should be evenly spread with more or less every hexagram represented roughly an equal number of times. But this is far from being the case. Indeed, nine hexagrams had never been obtained in this period while another nine had occurred four or more times. This suggests that the meaningfulness of the hexagrams is indeed a relevant factor in a reading, something that may be obvious to the devotee but needs to be pointed out to the sceptic. 6[1]

Now, an analysis of the probabilities involved in the yarrow stick method, by contrast, reveals some significant imbalances. While the expected number of moving lines is reasonable at 1.58 per hexagram, it turns out that a yin line is 1.6 times more likely to occur than a yang line and that a moving yang line is no less than 4.1 times more likely to occur than a moving yin line. 7[2] So this method is not genuinely random. Its results are likely to be biased in certain ways.

Finally, I offer a third alternative and simple method of consulting the I Ching that may appeal to some readers. It is genuinely random and produces a slightly lower mean of 1.42 moving lines per hexagram. Shuffle a standard pack of fifty-two cards and choose three without replacing them in the pack. Let a red card (diamond or heart) represent yin with a value 2 and a black card (club or spade) represent yang with a value 3. The total of the cards’ values is 6, 7, 8 or 9 as before and this provides the first line of the reading. The cards are now replaced in the pack, which is thoroughly shuffled, and the procedure is repeated five more times.

Enjoy this incredible book!