CHAPTER FOUR MY COLD DEAD HANDS

“If a lie is only printed often enough, it becomes a quasi-truth, and if such a truth is repeated often enough, it becomes an article of belief, a dogma, and men will die for it.”

—The Crown of a Life, Isa Blagden (1869)

In his book Political Parties (1911), Robert Michels, a German sociologist, wrote that all complex organizations, regardless of how democratic they start out, eventually develop into oligarchies (where a small group of people has control). It’s known as the “Iron Law of Oligarchy.”132

If an individual has risen to the top of their particular field, whether it’s in the business world, politics, or religion, we should naturally expect them to do everything in their power to stay on top, as they will have little motivation to change the system that got them there in the first place, unless, of course, those changes are designed to increase their power. As we saw in the last chapter, this desire to maintain the status quo inside their organizations can lead to a lack of reform and brutal attacks on criticism.

But what if the attacks come from outside the organization?

In this chapter, I want to explore the different kinds of tools the elite, some of whom are psychopaths, use to maintain their power and stage their war on the minds of the masses. The tools include religion, lobby groups, front groups, the corporate media, the education system, and the broader use of outright lies and propaganda.

It seems reasonable to assume that the elite will want to protect their organizations, and therefore themselves, from external criticism and reform, as much as they do from internal changes. This explains why such people are usually politically conservative—they want to conserve the status quo. Even if they vote for the less conservative of the major political parties in their country (for example, the Democratic Party in the USA, the Labor Party in the UK or the Australian Labor Party in Australia, etc.), you can bet they will still be relatively conservative on most issues that affect their wealth and power. They might be pro-gay marriage or support doing something about climate change or gun control—but what is their position on increasing taxes on the top 1 percent of income earners or increasing corporate tax rates? What is their view on increasing government regulations and oversight in their particular industry? What is their position on capping executive pay and bonuses or jail time for white-collar crime?

Take, for example, Qantas’ openly gay CEO Alan Joyce (Qantas is Australia’s largest airline). While very outspoken on issues like same-sex marriage, calling it “the morally right thing to do,” he also defends his $24 million salary,133 something others find morally unjustifiable.

You would expect them to be against policies that might have an impact on the continued success of their organization, which, in turn, would also affect their power. Things have been working out pretty well for them the way they are, so, naturally, they don’t want to shake the apple cart. I get it; I really do. But what’s best for their power isn’t necessarily what’s best for the rest of society. And you would expect them to use their control to fight for keeping the system stacked in their favor.

Let’s say that there is a political party that wants to pass legislation that might weaken an organization’s financial success—maybe deregulation of their industry, perhaps the introduction of new carbon emission regulations, possibly increasing the power of labor unions, and so on. What would you expect the CEO of an organization in that industry to do? I would expect her to try to use whatever power she has to prevent the political party from passing that legislation. And what tools does she potentially have at her disposal, as the CEO of a significant and financially successful corporation?

For a start, she probably has access to:

- Lots of money.

- Lots of lawyers.

- Lots of political influence.

- Lots of media influence.

- Lots of friends in high places—significant shareholders of her company who are also substantial shareholders of other significant corporations that also have lots of money, lawyers, and political and media influence.

And if her organization’s financial success is being threatened, would you expect her to use each of these tools to her advantage? I would. It just stands to reason. It doesn’t make her a terrible person—it just makes her human. She doesn’t have to be a psychopath to want to protect her lifestyle. The lengths that she is willing to go to protect it will determine whether or not she is a psychopath, but not the initial desire to preserve her lifestyle.

The desire of the people in the top ranks of our organizations to protect their power, and the loads of cash and influence they have at their disposal to do so, is the flaw that lies deep in the heart of capitalism.

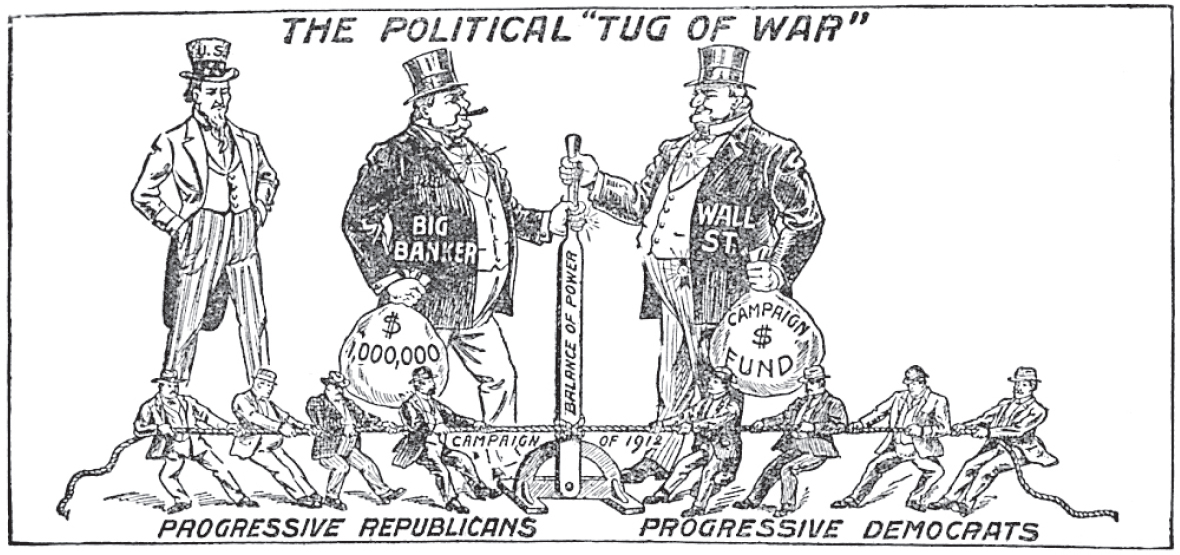

As Einstein pointed out, large organizations usually control immense power and the means to influence democracy well beyond the reach of any individual or even most groups of concerned citizens—and even more power than most political parties. The only thing that can get in their way is usually another equally influential organization with interests that are not precisely aligned. In these situations, we see a struggle for domination between organizational interests. The people sit on the sidelines and watch—or don’t watch. How often is the general public aware of the backroom meetings between lobbyists and politicians where they discuss the text of upcoming legislation? Rarely. These meetings are rarely made public and seldom covered by the media. Sometimes, like the negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, they are kept secret by corporations and politicians.134

Businesses, in particular, have a lot of influence on which stories are given coverage in the corporate media. This influence takes many forms. In some cases, it may be a direct influence. For example, the business or its principal shareholders or executives may also be significant shareholders in the media company (especially when a small number of companies control most of the media)135 and can exercise their seat on the board or their friendship with members of the board or a threat to dump stock (i.e., sell it cheaply) and drive down the share price (which can cause a range of problems for management and shareholders) to influence the stories that get covered and to what extent.

Alternately, a business may use an indirect form of influence via their advertising budget. As the primary source of revenue for most media corporations comes from advertising—selling access to customer attention—a business that threatens to withhold its advertising spend from a media organization can often get them to pay attention to whatever agenda they have. The CEO calls the publisher and threatens, “If you run that story, then we’ll pull all of our advertising and give it to your competitor paper/TV station/website.”

A DIFFERENT KIND OF TRUTH

Some people think propaganda only happens in third-world dictatorships, with a cult of personality built up around the “glorious leader” and dramatic posters depicting how the population is genetically or morally superior to others. But that’s only one kind of propaganda. In the West, we have just as much, if not more, propaganda in our daily lives, but because we’ve grown up knowing nothing different, we don’t even notice it.

According to French philosopher and sociologist Jacques Ellul, most people are easy prey for propaganda,

“because of their firm but entirely erroneous conviction that it is composed only of lies and ‘tall stories’ and that, conversely, what is true cannot be propaganda. But modern propaganda has long disdained the ridiculous lies of past and outmoded forms of propaganda. It operates instead with many different kinds of truth—half truth, limited truth, truth out of context.”136

We need to understand that modern propaganda is far more sophisticated and insidious than the kind Big Brother uses in the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

We get the word propaganda from the Vatican. The Congregatio de Propaganda Fide or “congregation for propagating the faith” is a committee of cardinals established 1622 by Gregory XV to supervise foreign missions. Propaganda means “to propagate.”

Propaganda is defined today as any form of indoctrination in which one group systematically uses manipulative methods to persuade others to conform to a particular way of thinking, any movement to propagate some practice or ideology. Another word for it is simply brainwashing. And we are all brainwashed from the day we are born, by our governments, media, and corporate and religious leaders—the very people we are told we should trust, the very people we are told are looking out for us, the very people who have control of our money, our politics, our education, our information, our spiritual path, and our military.

And they have to do it. The elite, the psychopaths, know that if we wanted to, the public could start a revolution and cripple the economic system that keeps them on top at any time. To prevent that, we need to be kept ignorant of the relevant facts, overworked, poor, heavily in debt, and distracted. And all of that takes systematic brainwashing. To keep the public from organizing and revolting, it’s imperative to brainwash them into believing what the elite are doing is right, ethical, and just and that we are poor because we just didn’t work hard enough—but we might get there one day if we just keep on believing.

It reminds me of Joe Bageant’s description of his “dittohead friend Buck” in his book Deer Hunting with Jesus:

He believes in the American Dream as he perceives it, which is entirely in terms of money. He wants that Jaguar, the big house, and the blonde bimbo with basketball-size tits. At age thirty-nine and divorced, he still believes that’s what life is about and is convinced he can nail it if he works hard enough. The sports car, the Rolex, McMansion, the works.137

It’s like some form of Stockholm Syndrome, where hostages develop sympathetic sentiments toward their captors and end up sharing their opinions and acquiring romantic feelings for them as a survival strategy during captivity.

David Hume, the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher, was fascinated with “the easiness with which the many are governed by the few, the implicit submission with which men resign.” In his book Of the Original Contract, he said that in all societies throughout the world, the real power is in the hands of the governed. So why don’t they overthrow their governments and take control of the power? He concluded that the people are governed by either force or by control of opinion. Control their attitudes, their beliefs, and you can control the power. According to Hume, this “extends to the most despotic and most military governments, as well as to the freest and most popular.”

Those of us fortunate to live in a democracy are taught that our governments are “for the people, by the people,” and we naturally assume this means we aren’t being lied to or manipulated. Whether you live in the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, France, Germany, or any other developed, democratic, capitalist country, there is a reasonable chance that you are being lied to, day in and day out. Of course, not everything you hear is a lie. And perhaps “lie” is too strong a word. Let’s call it being “finessed”—after all, Orwellian newspeak is part and parcel of how the system works!

The idea that we all live in a free democracy, where everyone has equal rights, and an equal say in how society works, is an illusion that has been engineered and perpetuated by the largest of our organizations for as long as our countries have existed. Understanding why these illusions have been created and why they will remain until we re-engineer society is part of the journey to understanding the modern world.

If you asked most astronomers in the early sixteenth century what astronomy was all about, they probably would have told you that it was the study of how the stars and planets revolved around the Earth. The very definition of what they did prevented them from realizing the truth—that the Earth revolved around the Sun with the rest of the planets in our solar system. Sometimes our illusions about how things work can be so influential that they prevent us from seeing the truth—even when it is right there in front of our eyes.

Noam Chomsky, institute professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, author, political activist, and considered the world’s leading intellectual,138 stated in a 2013 interview that the United States is “no longer a functioning democracy, we’re really a plutocracy.”139 And that was several years before Trump won the White House!

Plutocracy is government by the wealthy. Of course, this has been the most common form of government throughout history. Whether we call them kings, emperors, or presidents, the people with political power are usually either wealthy themselves or are financially supported by the wealthy. Recognizing that this is how our so-called democratic governments work today helps us to develop a model that explains a lot of how our propaganda system works.

Unfortunately, the models most of us have been given for understanding how our societies work are broken.

Those of us fortunate enough to have been born in the developed world after World War II have been indoctrinated relentlessly by our governments, by the corporate media, and by corporate advertising. We have been sold a story about how wonderful our societies are and how we fit into that picture. It’s not that much different from the kinds of propaganda we would expect in the Soviet Union or under Kim Jong-il.

We have been sold that story for so long and so persuasively that we believe it to be true. Billions of dollars are spent every year reinforcing these ideas in our brains. The indoctrination is so pervasive that it is tough for people to pull themselves out of it.

One of the most prominent ways that we are brainwashed is through corporate media. It’s essential to remember that they are for-profit corporations and that they exist for the same reason all for-profit corporations do—to make money for their stakeholders.

Like drug dealers in a depressed urban environment, corporations, especially if they are run by psychopathic cultures, don’t care about the health of their customers. They probably don’t want their customers to die as that will interfere with the source of the money. However, if a few die here and there—or if the people dying weren’t going to contribute to profits in the first place—then that’s okay. That’s collateral damage. There are always going to be more customers out there to replace them.

PROPAGENDA

The propaganda in Western countries has become so ubiquitous, sophisticated, and disciplined during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries that someone coined a new term for it—propagenda. Propagenda is the act of creating an environment in which only a specific range of topics are allowed for discussion. Discussions about issues that don’t fit the decreed agenda are prevented from getting coverage by the media, the politicians, or the organizations that enable them. They are ignored, obfuscated, shut down, or covered up. You have been conditioned, not just to believe the lies, but not even to notice them.

In their book, Manufacturing Consent (1988), Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky proposed a theory called “The Propaganda Model” for explaining how the populations of Western democratic countries are kept calm and obedient by the “power elite.” Herman and Chomsky demonstrate that there are systemic biases, supported by a series of “filters,” in the mass media that have fundamental economic causes. These filters ensure that only the people who have the right biases, which essentially agree with the worldviews of the elite, can get employed and to build a career in the media and academia. Everyone else is either filtered out—fired or prevented from rising through the ranks—or filter themselves out by resigning.

The Australian social psychologist Alex Carey, the first person to provide a dedicated analysis of modern propaganda in democracies, wrote that

The twentieth century has been characterized by three developments of great political importance: the growth of democracy, the growth of corporate power, and the growth of corporate propaganda as a means of protecting corporate power against democracy.140

According to Carey, the extension of the right to vote and the rise of the union movement in the first half of the twentieth century were perceived as threats to corporate power. This threat was met by learning to use propaganda “as an effective weapon for managing governments and public opinion.”

Corporate propaganda has two main objectives: to identify the free-enterprise system in popular consciousness with every cherished value, and to identify interventionist governments and strong unions (the only agencies capable of checking the complete domination of society by the corporations) with tyranny, oppression and even subversion.

One thing that many people don’t realize is that, in the first half of the twentieth century, there were robust newspapers that not only took a strong stance against capitalism and imperialism but also had a very significant readership.

For example, in 1933, the Daily Herald, a British newspaper that had opposed British involvement in World War I, supported British industrial strikes, supported the Russian Revolution but later condemned the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the Soviet invasion of Finland, became the world’s best-selling daily newspaper and even into the 1960s had almost double the readership of The Times, the Financial Times and the Guardian combined.

According to James Curran, professor of communications at Goldsmiths University of London and author of Media and Power, the Herald was a “freewheeling vehicle of the left, an important channel for the dissemination of syndicalist and socialist ideas.” Even though it achieved 8.1 percent of national daily circulation, the paper only received 3.5 percent of net advertising revenue, significantly impacting its ability to survive.

Corporate advertisers aren’t likely to support a newspaper that actively speaks out against capitalism. As British journalist Andrew Marr wrote in his memoir, My Trade: “It’s hard to make the sums add up when you are kicking the people who write the checks.”

The paper staggered on until 1969 when it was bought by a then little-known Australian newspaper owner called Rupert Murdoch who turned it into the sexist, celebrity-obsessed, news-lite The Sun. The first headline under Murdoch was “HORSE DOPE SENSATION.”

It still has one of the highest circulations of all British newspapers, but of course, it has dispensed with supporting the political issues for which it was initially known.

As U.S. media analyst Robert McChesney succinctly put it, “So long as the media are in corporate hands, the task of social change will be vastly more difficult, if not impossible.”141

“Propaganda is to democracy what violence is to a dictatorship.”

—Noam Chomsky

Every news editor or radio or television news producer knows that they have a limited number of inches or minutes to fill with content every day. And there are countless stories to fill them with. How do they decide which stories they are going to cover?

They take into consideration a combination of factors.

- Is it going to generate attention from our readers, listeners, or viewers? Keep in mind that all corporate media exists to make a profit, typically by selling access to the brains of their audiences to other businesses in the form of advertising. The more attention they can create with their news, the more advertising revenue they can generate from it.

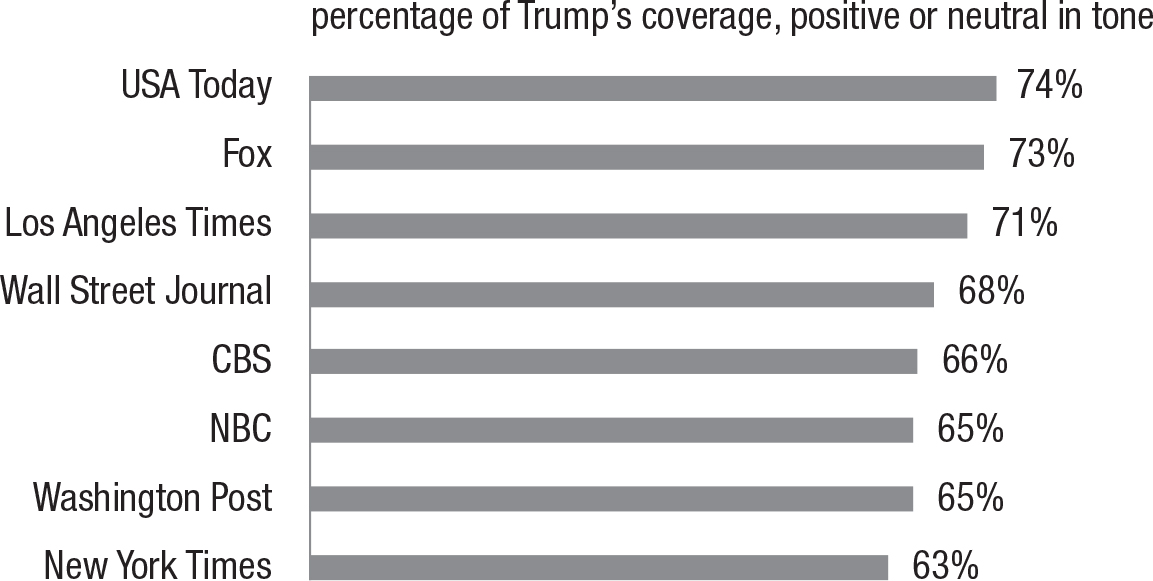

- Does it fit with the existing narrative that we, as a media organization, are promoting? Media companies spend a lot of time trying to work out who their target audience is. Example: Fox News’s target audience is older, conservative, religious, white people. The same is true for most of News Corporation’s global media properties (except maybe their movies and some of their spin-off cable channels like FXX) and their interests in China. So, if your target audience is older, conservative, religious, white people, and that’s who you are trying to sell to advertisers, you are going to choose the news that you show them carefully. It has to map to the narrative to which you’ve previously held. If you’ve spent years reinforcing a particular narrative, and you suddenly choose news stories that conflict with it (e.g., if you started saying the insane size of the military budget and not illegal immigrants are the primary cause of America’s economic problems), at best you’re going to confuse your audience—at worst, you’ll piss them and your advertisers off. It’s crucial to select stories that reinforce your narrative.

- Does it fit with our overall corporate goals? If a media company is owned by a parent company that also makes billions of dollars from manufacturing and selling weapons, which are sold to Saudi Arabia (for example NBC when GE owned it), then you are unlikely to take a hard stance in your news coverage about how U.S. arms sales to the Saudis often end up in the hands of terrorist organizations.

Here’s an example of the last scenario.

In 2010, it was widely covered in the global news that President Obama had agreed to sell a record $60 billion of arms to Saudi Arabia. A quick Google search for “$60bn Saudi arms sale” returns nearly 10,000 entries. It was reported by The Guardian, Al Jazeera, BBC, Financial Times, The Independent, Wall Street Journal, and so forth.

But when I tried the same search on NBC’s website, I couldn’t find a single story covering the sale.

Another example: in 2010, it was widely reported that the United States also reached a separate $25.6 billion deal to sell the Saudis military helicopters, some manufactured by General Electric.

Again, that news was covered by many major news agencies—but not NBC.

THE FOURTH ESTATE

The media used to be called the “Fourth Estate,” which comes from the days in England when there were three primary centers of power—the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. The press was called the fourth estate, the fourth center of power.

Oscar Wilde once wrote:

In old days men had the rack. Now they have the Press. That is an improvement certainly. But still it is very bad, and wrong, and demoralizing. Somebody—was it Burke?—called journalism the fourth estate. That was true at the time no doubt. But at the present moment it is the only estate. It has eaten up the other three. The Lords Temporal say nothing, the Lords Spiritual have nothing to say, and the House of Commons has nothing to say and says it. We are dominated by Journalism.142

The original role of the Fourth Estate was to keep the others honest.

When for-profit corporations run the news media, it makes sense that the news they choose to cover will mostly, if not always, fit neatly within the model of society that the corporations wish to promote. It would not serve for a corporation to run many news stories that might have the long-term effect of reducing their profits. Remember—corporations are, above all else, survival machines. They exist to maintain power. And if psychopaths rise to the top of the media organizations, how do you think they will use them?

Stories that question the values of our society will struggle to see the light of day. For example, how many stories have you seen in the mainstream media that argue against capitalism or the corporatocracy? It’s certainly not the case that those arguments can’t be made. They do get made, in alternative media and in books. But you won’t often see them in the mainstream media because they run counter to the values of the corporation.

In the same way, you wouldn’t expect a media organization to give fair coverage to scandals involving their own company.

During the 2012 Levenson inquiry into the culture, practices, and ethics of the British press following the News International phone-hacking scandal, evidence emerged that Rupert Murdoch and his papers wield enormous influence over both the Labour and Conservative parties in the UK. The conclusion reached by a committee of UK ministers was that “Rupert Murdoch is ‘not a fit person’ to exercise stewardship of a major international company.”143

The committee concluded that the culture of the company’s newspapers “permeated from the top” and “speaks volumes about the lack of effective corporate governance at News Corporation and News International.”

And they didn’t just point the finger at Rupert. They pointed it at the entire leadership of News Corp.:

The committee concluded that Les Hinton, the former executive chairman of News International, was “complicit” in a cover-up at the newspaper group, and that Colin Myler, former editor of the News of the World, and the paper’s ex-head of legal, Tom Crone, deliberately withheld crucial information and answered questions falsely. All three were accused of misleading parliament by the culture select committee.”144

A very telling example of how media companies manipulate the news they choose to cover is too look at News Corporation’s coverage of the phone-hacking scandal.

The Australian Centre for Independent Journalism at the University of Technology Sydney (which, unfortunately, closed down in 2017) once analyzed News Corp’s handling of its own terrible press.145 They looked at one week of coverage of the inquiry in a range of Australian papers, including those owned by News Corp (which make up 70 percent of Australian print media). They found that while News Corp’s newspapers did mention the inquiry, they ran far fewer stories than non-newspapers, and what they did run was buried deep in the paper, and relied mostly on commentary and editorial, much of which was critical of the inquiry.

Not one editorial supported the idea that there should be a similar inquiry into Australia’s media.

In the week under review, no News Ltd paper acknowledged any problems for News Corporation’s power or practices other than phone hacking. And phone hacking was only denounced in editorials once a statement was issued by News CEO John Hartigan describing phone hacking as “a terrible slur on our craft.”

We can see from this small example that corporate media will usually strive to protect its interests and the interests of its industry—logical behavior, to be sure, but it helps us understand the inherent bias that exists at the heart of our news media.

And what do we know about the quality of the news media? A separate study run by the ACIJ found that across ten hard-copy Australia newspapers, “nearly 55 percent of stories analyzed were driven by some form of public relations—a sad indictment on the state of Australian reporting.”146

People working in the news media, for example, journalists, editors, and so forth, will often argue that there is no bias and that they are faithfully reporting the news as best they can. However, as Chomsky and Herman pointed out in Manufacturing Consent, this is what you would expect. Organizations, being survival machines, tend to hire and promote people who “buy into” the mission and purpose of the survival of the institution.

And yet sometimes the curtain is briefly drawn aside, and we get a short glimpse of the wizard revealed in his true colors.

According to an interview on ABC Radio on June 2012, one of Australia’s most prominent businesspeople argued that the board of a newspaper should have the right to influence the editorial direction of the company’s media outlets, especially if the actions were designed to increase the company’s profits. Channel Ten (a leading Australian TV network) board member and Hungry Jacks (Australia’s version of Burger King) founder, Jack Cowin, told ABC Radio that newspapers are a business, not a public service and that the board has the right to decide what kinds of stories that business should cover.147

Cowin also happens to be one of the closest advisers to Gina Rinehart, the mining magnate who tried to buy control of one of Australia’s leading newspapers. When Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison had a state dinner with Donald Trump in September 2019, guess who he took as his honored guest? Gina.

As we can see, “editorial independence” isn’t a clear-cut issue.

Any student of the history of newspapers already understands that papers have always been used for political and commercial influence.

According to Michael Wolff’s 2008 book, The Man Who Owns The News, Rupert Murdoch entirely altered the political landscape in New York within his first year of owning the New York Post in the mid-1970s:

He decides to use the Post as an instrument to elect somebody—he understands that it doesn’t really matter whom, just that the Post be responsible. After interviewing each of the prospective candidates for New York City mayor, he settles on the perhaps least likely guy—that is, the one who needs him the most. It’s Ed Koch, a congressman from Greenwich Village… The entire paper is put in service to the Koch election. The Post is transformed into an ebullient narrative of Koch’s presence, charm, and inevitability. The least charismatic man in the city becomes the most charismatic.148

When Koch was elected mayor of New York in 1977, Murdoch became one of the most influential people in the city. And this is only a few years after he arrived in New York and had been seen by the “old money” as easy picking. Koch was Murdoch’s first American political coup. Of course, nearly forty years later, another Murdoch media entity, Fox News, would play an enormous role in getting Donald Trump elected president of the United States.

Going back to the late nineteenth century, the term yellow journalism was coined by Erwin Wardman, the editor of the New York Press, to reflect the first “media war”—Pulitzer versus Hearst. Circulation battles between Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal culminated in both of the papers using scandal-mongering, outlandish headlines, and rampant sensationalism to try to outsell each other.

One of the turning points in the history of propaganda was the Spanish-American War (April–August 1898). Hearst and Pulitzer both fabricated stories and embellished others to increase circulation and justify American intervention, which led to a war and even greater circulation. This strategy was immortalized in fiction in Orson Welles’ masterpiece Citizen Kane. Kane, the young, ambitious newspaper proprietor, receives a telegram from his reporter in Cuba, who says there isn’t any war to report on, so he’s spending his time writing poems. Kane issues the smug reply:

“You provide the prose poems—I’ll provide the war.”149

In Britain during the early twentieth century, Murdoch’s predecessors, press barons like Max Aitken (aka Lord Beaverbrook) owner of the Daily Express, and Alfred Harmsworth (Lord Northcliffe), owner of the Daily Mail and The Times, were both heavily involved in anti-German propaganda that promoted Britain’s involvement in World War I. One of their competitors claimed that “next to the Kaiser, Lord Northcliffe has done more than any living man to bring about the war.”150

Northcliffe, who controlled 40 percent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 percent of the evening, and 15 percent of the Sunday circulation, actually played a huge role in getting Lloyd George elected prime minister in 1916. For his efforts, he was offered a position in the cabinet. He turned that down—and was officially made “director of propaganda” instead. Imagine Rupert Murdoch being given the same title and you get how ludicrous this was. A media baron, who thought of himself as Napoleon reborn, being given a role in the government.

In return for supporting Lloyd George’s coalition government in the 1918 general election, Northcliffe demanded the government accept a list of the names of people who should be given roles in his government. To his credit, Lloyd George refused. That’s just one example of how the “free press” works in the West.

In more recent times, we have seen the role of Judith Miller at the New York Times in publishing propaganda that helped lead the U.S. into its invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Since her early days at the Times, when she inserted CIA misinformation into a piece on Libya, she’s always been a tool of power. She was the voice of the Defense Department, embedded at the Times. She was hyping bullshit stories about Iraq’s WMD capabilities as far back as 1998, and in the run-up to the war, her front-page scoops were cited by the Bush administration as evidence that Saddam needed to be taken out, right away… Lying exile grifter Ahmed Chalabi fed her the worst of the nonsense designed to push America into toppling Saddam Hussein (and giving Iraq to him), and she pushed that nonsense into the newspaper of record. She got everything wrong.

Miller used Chalabi as an anonymous source for her reporting about Saddam’s efforts to build a nuclear weapon. Chalabi was born into one of Iraq’s wealthiest and most influential families. He left the country after the military coup in 1958 and lived most of his life in the United States. In the intervening years, Chalabi became a banker (the family business) and, after a bank he founded in Jordan collapsed, was convicted and sentenced in absentia to twenty-two years in prison for bank fraud. In 1992, he created an Iraqi opposition group, the INC, that was mainly funded by the United States. Chalabi used some of the funding to hire U.S. lobbying group BKSH & Associates to help him sell the idea of overthrowing Saddam to the American public. Two of the founders of BKSH were Paul Manafort, Donald Trump’s former campaign manager, who is currently serving time for five counts of tax fraud and two counts of bank fraud—and Roger Stone, who served as an advisor to the Trump campaign.

Miller didn’t mention anything about Chalabi’s background of fraud and corruption, his role with the INC, his funding by the U.S. government, or the lobbying firm he hired, when she published her stories in the New York Times. And the U.S. government, led by Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld, used her stories to back up their argument that Saddam was building weapons of mass destruction and that Iraq needed to be invaded.

So, to put it another way—the U.S. government gave Chalabi tax dollars, which he used to hire a lobbying firm. This firm helped him get anonymous, positive, and unquestioning coverage in the New York Times, which the U.S. government then used to justify a considerable military build-up and the invasion of Iraq—also paid for by tax dollars, much of which ended up in the hands of American businesspeople.

Is it any wonder, then, that, according to at least one study,152 the media is now the least trusted institution in the world? According to Glenn Greenwald of The Intercept, “featuring lobbyists and corporate consultants to analyze the news without disclosing their glaring conflicts of interest” is “a scandalous media-wide practice.”153

In late 2018, he revealed that the Daily Beast, MSNBC, PBS, and CNN all used tainted sources to comment on Saudi Arabia and the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. He had previously disclosed that The Washington Post, Khashoggi’s employer at the time of his death, simultaneously hired journalists “who maintain among the closest links to the Saudi regime and have the longest and most shameful history of propagandizing on their behalf.” If this practice is as widespread as Greenwald suggests, where do we turn for a trusted analysis of events?

THE INTELLIGENT FEW

While propaganda has been around in some form since the dawn of humanity, the origin of modern public relations stems from World War I and perhaps the supreme PR story of all time.

As hard as it may be to believe, in the early twentieth century, the United States’ military was outnumbered by Germany’s by a factor of twenty. For the first couple of years of WWI, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson had advocated neutrality “in thought and deed” for the United States, and most of the country agreed with him. The war happening in Europe—a ridiculous war that should never have happened—had nothing to do with America.

Then, as now, there were fortunes to be made during a major war. America’s neutrality enabled their bankers and manufacturers to finance and supply all sides of the conflict. And they did.

The British, however, with their superior navy, were able to blockade Germany and prevent America from trading with them. In response, the Germans announced that they would use submarines to attack any ships trading with England. This led to some bright spark in the USA deciding to try to ship ammunition to England undetected in the holds of unarmed passenger ships.

Of course, the Germans found out about this cunning and dangerous strategy, and on May 7, 1915, they torpedoed the RMS Lusitania, a passenger ship that was secretly carrying four million rounds of .303 bullets from the USA to England. Both the UK and the USA long denied that the Lusitania was carrying ammunition, but evidence of the cargo was discovered in the wreckage ninety years later. The sinking of the Lusitania, which happened to be carrying 128 Americans among its passengers, began the process of changing American attitudes about entry into the war. (Of course, there was no punishment for the individuals or corporations who were responsible for putting the ammunition in the hold of the ship and endangering the lives of the civilians.) Wilson, though, ran for election again in 1916 (and won) on a neutrality ticket. The sinking of the Lusitania, although long held as the reason America entered the war, really had little to do with it. It wasn’t even an American ship. The Germans agreed to halt using torpedoes to sink ships, and Wilson was happy.

Unfortunately, the Germans flip-flopped on the torpedo issue, which upset the Americans. The Germans also tried, unsuccessfully, to get Mexico to attack the U.S., which they found out about and weren’t very happy about that either.

Neither of these things, however, were the primary cause of America’s entry into the war. As usual, the real reasons were economic. When we want to understand the causes of many political events, we should follow the advice of the Watergate informant Deep Throat and “follow the money.” Or, as the ancient Roman statesman Cicero put it “cui bono” (who benefits?).

The U.S. had huge economic investments with the British and French in the lead up to WWI. The Allies (mainly Britain and France), together with their colonies, had purchased 77 percent of American exports in 1913—which was all the more significant because the American economy had been struggling at the time. According to banker J. P. Morgan:

The war opened during a period of hard time that had continued in America for over a year. Business throughout the country was depressed, farm prices were deflated, unemployment was serious, the heavy industries were working far below capacity, [and] bank clearings were off.154

In the first couple of years after the start of the conflict (before the Americans got directly involved), the Allies purchased a lot of American steel, bolstering the American economy. But the Allies were cash poor, so they had to buy the steel, and other American products, on credit. The Allies took out the biggest loan in financial history from private American banks—brokered of course by Morgan. He also negotiated a deal that positioned his company as the sole munitions and supplies purchaser during World War I for the British and French governments. His cut was a 1 percent commission on $3 billion—about $30 million in 1914 or $753 million in today’s dollars.

By the way, Morgan’s father, J. P. Morgan Sr., actually created the corporation called U.S. Steel, which, at one point, made 67 percent of all the steel produced in the United States and was known on Wall Street as just “The Corporation” due to its overwhelming size and importance. You have to admire his son’s chutzpah—as a banker, he profited by organizing the loans to Britain and France; as the owner of U.S. Steel, he benefited again from the spending of those loans on steel, as well as earning a one percent commission on purchases of cotton, chemicals, and food.

If the Allies were to lose, then they would not be able to pay the banks back (amounting to about $2 billion 1917 dollars), which could cause the U.S. economy to collapse (or so the thinking went at the time). Wilson needed to reverse his position and find a way to convince the American people to get involved in a war he had been saying for two years had nothing to do with them.

To finance the war effort, the government tried to sell “Liberty Bonds.” A bond is, simply put, when the government says, “Loan me your money, and we’ll pay you back later with interest.” But the U.S. public was unenthusiastic, and the government struggled to get the people to hand over their cash.

And that’s where the Committee on Public Information came into effect. CPI was charged by President Wilson to “engineer the consent” of the American people for their involvement in World War I. CPI was an independent agency of the government, but it was composed by the Secretary of State, the Secretary of War, and the Secretary of the Navy, so it actually wasn’t all that independent. The fourth member of the committee was the civilian Chairman George Creel, an “investigative journalist.”

Creel gathered the nation’s artists to create thousands of paintings, posters, cartoons, and sculptures promoting the War. He also gathered support from choirs, social clubs, and religious organizations to join “The World’s Greatest Adventure in Advertising.” He recruited about 75,000 “Four-Minute Men,” who spoke about the war at social events for an ideal length of four minutes, considered at that time to be the average human attention span. They covered the draft, rationing, bond drives, victory gardens, and why America was fighting. It was estimated that by the end of the war, they had made more than 7.5 million speeches to 314 million people.

This was, of course, in the years before radio, film, television, and Netflix had any significant penetration. Imagine the same kind of thing happening today—the government organizing tens of thousands of people to travel around the country giving propaganda speeches to convince the people to go to war.

To help sell the Liberty Bonds, Morgan also bought a controlling interest in twenty-five of the top American newspapers. He wanted to make sure he got paid back a $400 million loan to Britain from the first Liberty Bond drive. The “isolationists continued to accuse the House of Morgan of whipping up pro-war sentiment.”155

After this massive propaganda campaign, the number of Americans ready to go to war rose from roughly 380,000 in 1915 to 4.8 million in all the military branches by the end of World War I.

Of course, none of the reasons why the U.S. had initially stayed out of the war had changed. It still had little chance of spreading to North America. The Mexicans had no intention (or capability) of launching an attack on the U.S. It was justified to the American people using the usual hyperbole, used by autocrats and imperialists since the dawn of time—by resorting to Pavlovian triggers such as “peace,” “justice,” and “freedom.” However, it is quite clear that the U.S. entered WWI largely because of economic reasons.

In the end, World War I cost the American public about $33 billion ($828 trillion when adjusted for inflation), a sum sufficient to have carried on the Revolutionary War continuously for more than 1,000 years at the rate of expenditure that war involved. About two-thirds were for direct costs; the remainder (over $10 billion) was loaned to America’s allies—who never paid it back.

The U.S. was debt-free before the war. After the war, it had a public debt of $25 billion.156

Why would the U.S. spend $33 billion to recover $2 billion in loans? That doesn’t seem to make much sense. But when you realize that it was the banks who loaned most of the money and the people who funded the war (via their taxes and “Liberty Bonds”), then it starts to become quite clear. It’s the same model for Western countries getting involved in foreign wars today. Use public funds to fight the war, while private corporations benefit from the result, through reconstruction contracts and trade agreements with the government of the post-war country. It’s another form of the socialization of costs and the privatization of benefits. It’s like getting your friends to invest in your business and then keeping all of the profits for yourself and justifying it by saying they are all better off because there is one more successful business in town. I’ll go into it in more detail later on in the book.

The Committee on Public Information was the engine behind the reprogramming of the American people. Their success in motivating the U.S. to support a war has been studied, repeated, and refined by successive administrations over the last century. And it expanded to become a global propaganda campaign.

The founder of modern propaganda, Edward Bernays, a nephew of Sigmund Freud, worked for the CPI. Just after WWI, he issued a press release that stated CPI’s role after the war was to keep up “a worldwide propaganda to disseminate American accomplishments and ideals.”

In the opening of his classic 1928 book Propaganda, Bernays explained his view of its role in modern Western societies:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Clearly it is the intelligent minorities which need to make use of propaganda continuously and systematically. In the active proselytizing minorities in whom selfish interests and public interests coincide lie the progress and development of America. Only through the active energy of the intelligent few can the public at large become aware of and act upon new ideas.157

Another of my favorite examples of the power of brainwashing by the military-industrial complex is that of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States in 1945. Within the first two to four months of the attacks, the acute effects killed 90,000–166,000 people in Hiroshima and 60,000–80,000 in Nagasaki, with roughly half of the deaths in each city occurring on the first day. The vast majority of the casualties were civilians.

In the seventy-three years that have passed since Hiroshima, poll after poll has shown that most Americans think that the bombings were wholly justified. According to a survey in 2015, fifty-six percent of Americans agreed that the attacks were justified, significantly less than the 85 percent who agreed in 1945 but still high considering the facts don’t support the conclusion.

The reasons most Americans cite for the justification of the bombings is that they stopped the war with Japan; that Japan started the war with the attack on Pearl Harbor and deserved punishment; and that the attacks prevented the Americans from having to invade Japan causing more deaths on both sides. These “facts” are so deeply ingrained in most American minds that they believe them to be fundamental truths. Unfortunately, they don’t stand up to history.

The truth is that the United States started the war with Japan when it froze Japanese assets in the United States and embargoed the sale of oil the country needed. Economic sanctions then, as now, are considered acts of war.158

As for using the bombings to end the war, the U.S. was well aware in the middle of 1945 that the Japanese were prepared to surrender and expected it would happen when the USSR entered the war against them in August 1945, as pre-arranged between Truman and Stalin. The primary sticking point for the Japanese was the status of Emperor Hirohito. He was considered a god by his people, and it was impossible for them to hand him over for execution by their enemies. It would be like American Christians handing over Jesus, or Italian Catholics handing over the pope. The Allies refused to clarify what Hirohito’s status would be post-surrender. In the end, they left him in place as emperor anyway.

One American who didn’t think using the atom bomb was necessary was Dwight Eisenhower, future president and, at the time, the supreme allied commander in Europe. He believed:

Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and… the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of “face.”…159

Admiral William Leahy, chief of staff to Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, agreed.

It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.160

Norman Cousins was a consultant to General MacArthur during the American occupation of Japan. Cousins wrote that

MacArthur… saw no military justification for the dropping of the bomb. The war might have ended weeks earlier, he said, if the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor.161

If General Dwight Eisenhower, General Douglas MacArthur, and Admiral William Leahy all believed dropping atom bombs on Japan was unnecessary, why do so many American civilians still today think it was?

Probably because they have been told to think that, repeatedly, in a carefully orchestrated propaganda campaign, enforced by the military-industrial complex (that Eisenhower tried to warn us about), that has run continuously since 1945.

As recently as 1995, the fiftieth anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Smithsonian Institute was forced to censor its retrospective on the attacks under fierce pressure from Congress and the media because it contained “text that would have raised questions about the morality of the decision to drop the bomb.”162

On August 15, 1945, about a week after the bombing of Nagasaki, Truman tasked the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey to conduct a study on the effectiveness of the aerial attacks on Japan, both conventional and atomic. Did they affect the Japanese surrender?

The survey team included hundreds of American officers, civilians, and enlisted men, based in Japan. They interviewed 700 Japanese military, government, and industry officials and had access to hundreds of Japanese wartime documents.

Less than a year later, they published their conclusion—that Japan would likely have surrendered in 1945 without the Soviet declaration of war and without an American invasion: “It cannot be said that the atomic bomb convinced the leaders who effected the peace of the necessity of surrender. The decision to surrender, influenced in part by knowledge of the low state of popular morale, had been taken at least as early as 26 June at a meeting of the Supreme War Guidance Council in the presence of the Emperor.”

June 26 was six weeks before the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. The emperor wanted to surrender and had been trying to open up discussions with the Soviets, the only country with whom they still had diplomatic relations.

According to many scholars, the final straw would have come on August 15 when the Soviet Union, as agreed months previously with the Truman administration, were planning to declare they were entering the war with Japan.

But instead of waiting, Truman dropped the first atomic bomb on Japan on August 6.

The proposed American invasion of the home islands wasn’t scheduled until November.

ONE NATION UNDER GOD

If you’re in charge of a significant church, you’ll also want to keep your power, which means keeping your church powerful and keeping people religious. You’ll use your influence with your congregation, especially those who are business and political leaders, to make sure you do whatever you can to prevent societal changes that could affect your strength.

What kinds of societal changes would make a religion panic?

In his book One Nation Under God,163 Kevin Kruse explains how the idea of America as a Christian nation was promoted in the middle of the twentieth century when the business elite was worried about the direction the U.S. was heading, with the Roosevelt government’s New Deal, the rise of union power, and the popularization of the tenets of socialism. So they recruited a vast number of conservative clergymen to preach the connection between faith, freedom, and free enterprise—and paid them handsomely to do it.

Business leaders in the U.S. engineered and funded a long-term campaign to recruit religious leaders to associate any attempt to curb the excesses of big business with the evils of Soviet-style communism. As the Soviet form of communism contained state-mandated atheism, this message also worked in favor of the American religious leaders—the rise of socialist thinking wasn’t in their best interests either—and helped brainwash Americans into thinking that any attempt to regulate the free market was anti-Christian and anti-American.

Some preachers thought this connection with capitalism was disgusting and refused to participate. Those that did jump on board, however, were financially rewarded. They got personally wealthy, had large churches funded by grateful business leaders and were given lots of free media coverage.

One preacher who was very happy to lead the clarion call of capitalism was James W. Fifield Jr., the head of the First Congregational Church in Los Angeles. The members of his 100-room cathedral were mostly very wealthy, and Fifield ended up being called “The Apostle to Millionaires.” He bought a million-dollar mansion on Wilshire Boulevard and hired a butler, a chauffeur, and a cook. First Congregational paid him $16,000 a year. Adjusted for inflation, that would be roughly a quarter-million dollars today. And this was in the middle of the Great Depression. Praise Jesus! Fifield was a trendsetter for today’s obscenely wealthy preachers.

The irony, of course, is that, according to the New Testament, the earliest Christian communities practiced an early form of proto-communism!

Acts 4:32–35 tells us: “All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had… from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need.”

Fortunately, not many Americans actually read the Bible, so the contradiction wasn’t evident.

It was as a result of these efforts that the phrase “In God we trust” became the official motto of the United States. Originally appearing as a verse in “The Star-Spangled Banner,” it had appeared on coins intermittently since the Civil War, although Theodore Roosevelt tried to have it removed, believing it was sacrilege. It wasn’t until 1955 that Congress decided to put it on paper money, and in 1956, it became the country’s first official motto.

And it wasn’t until Ronald Reagan that the phrase “God bless America” started being used to close presidential speeches. According to authors David Domke and Kevin Coe, before Reagan, only one president had used that phrase to close out an address—Richard Nixon trying to talk his way out of the Watergate scandal in 1973.164

HAVE A LITTLE FAITH IN ME

Political and business leaders have other reasons for promoting religion other than tying it to the prevention of socialism. “Religion is excellent stuff for keeping common people quiet,” said Napoleon Bonaparte, and the above stories suggest that business and political leaders in the United States see religion as a useful tool for maintaining social order.

If you can convince the general public that faith is at least as meritorious as reason and evidence-based decision making, perhaps it is a lot easier to get them to support other nonreligious initiatives that cannot be bolstered by evidence—such as Ponzi schemes (named after Charles Ponzi, an Italian swindler and con artist in the U.S. and Canada in the first half of the twentieth century).

For example, the FBI’s Utah Securities Fraud Task Force investigated why Mormons often fall victim to typical fraud schemes. It appears that the Latter-Day Saints are highly susceptible to “affinity fraud”—where a con artist preys on a group of people who share a common bond. In 2010, the FBI said its office in Salt Lake City was one of the top five places for Ponzi schemes.165

Sixty percent of Utah’s population is Mormon, which has made the state a prime target for religious-based affinity fraud, according to Utah’s Attorney General Sean Reyes.

Is it possible that the same propensity to fall for affinity fraud makes “people of faith” easier to deceive in other areas as well? Or, conversely, are people who tend to be more skeptical harder to convince of political arguments?

For example, if you had a skeptical population that was used to demanding evidence before they believed anything and their government said, “we need to invade Iraq because Saddam Hussein has weapons of mass destruction,” the population might reply “Well, show us some hard evidence, and we might believe you.”

However, if you have a population that has been trained to “just have faith,” then perhaps it is a lot easier to get their consent without having to worry about annoying little things like proof. It seems quite likely that one reason the Catholic Church was able to get away with hiding child rape for so many decades is that their congregations had too much faith in the clergy.

David Kuo, an evangelical Christian who served as special assistant to President George W. Bush and deputy director of the Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives, claimed that the White House used its faith-based initiatives program as a political tool to try to recruit “unconventional” Republican voters—including Christians among America’s poor minorities,166 while privately calling evangelical leaders “nuts,” “out of control,” and “goofy.”167

In the United States, polls have found that “78 percent of religious people display the flag on their clothing, in the office or at home, while only 58 percent of nonreligious do likewise. Evangelicals were the most likely to say they displayed the flag; those Americans unaffiliated with religion the least likely.”168 Side note: as an Australian, I find America’s obsession with its flag disturbing. That kind of thing doesn’t happen here. Or anywhere else I’ve traveled. It reminds me of the extreme nationalism of Nazi Germany.

Evangelicals also claimed America was the greatest country in the world at a far higher rate than Americans of other or no religious convictions. So at least in America, it seems there is a direct connection between being an evangelical Christian and being a patriotic nationalist.

Of course, having faith is not limited to religion. According to a 2005 Gallup poll, 22 percent of American adults believe in witches, and 36 percent believe in ghosts.169

Other Pew surveys have found that 26 percent of Americans believe in spiritual energy located in physical things such as mountains, trees, or crystals; and 25 percent profess belief in astrology (that the location of the stars and planets can affect people’s lives).170

Why do people still have faith in esoteric ideas in the twenty-first century? Possibly because it’s hardwired into us. This kind of thinking serves or used to serve, a fundamental purpose.

There are scientific theories that suggest that there are evolutionary biological reasons for humans, in days gone by, to accept on faith what their elders told them. For example, if a senior person in your tribe told you not to eat a certain kind of berry because it was poisonous, just accepting that theory on faith probably had survival advantages. If you were too skeptical about such pronouncements and ate the berry to see for yourself whether or not it was poisonous, you might not live long enough to pass on your skeptical genetics.

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, the Nobel Prize winner and the intellectual godfather of behavioral economics, Daniel Kahneman,171 explains the two different ways the brain forms thoughts. He refers to these ways as “System 1” and “System 2.”

System 1 thoughts are fast, automatic, frequent, emotional, stereotypic, and subconscious. These include the thoughts we have that confirm our existing models for how the world works. When we are presented with concepts that appeal to our cognitive biases, they allow us to think quickly and easily. Kahneman’s research shows that System 1 thinking makes us feel happy because it requires less effort and energy. However, it can also be easily fooled. Our “gut instinct” can often be wrong.

System 2 thoughts are slow, effortful, infrequent, logical, calculating, and conscious. They require more energy and effort, and, as a result, we tend to avoid them as much as possible.

An example of System 1 thinking is detecting that one object is more distant than another (easy, fast, requires no effort), while an example of System 2 thinking is parking in a narrow space (hard, takes initiative, and concentration).

If we can make decisions via System 1 quickly, easily, without having to engage our thinking muscle, the more mental energy we have to dedicate to other activities, like figuring out how to make more money or get laid (and I have a theory that the former is only useful because it helps the latter). If we have some kind of operating heuristic (rule of thumb) that allows us to make quick decisions about political, religious, and social issues, it saves us time and energy. If we merely accept that God exists, we don’t have to think too hard about alternative theories and their implications. This is all the more efficient if our parents and friends have the same heuristic. In days gone by, it meant our ancestors didn’t argue with tribal elders and risk being kicked out. When we assume our political party are the good guys and other parties are the bad guys, or when we assume that America always fights for freedom and the Russians are always evil, or that our prime minister is honorable, or that our CEO probably knows what she is doing, we are using System 1 thinking.

Unfortunately, System 1 plays right into the hands of the propagandists. If our brains have been saturated for decades with certain assumptions about how the world works, then it is easy for us to conform to those ideas. It requires much more effort to challenge those fundamental assumptions. It takes serious effort to train ourselves to ask hard, probing questions when watching the daily news. However, the more we force ourselves to think independently, the easier it becomes, especially as we build for ourselves new mental models for understanding how the world works.

Faith, in all its forms, makes life easier. You don’t have to think as hard. But does faith make life better?

Religious people might think that modern ills are directly related to a decline in faith, but the evidence suggests the opposite.

It might be a coincidence, but the countries on top of the OECD’s Better Life Index172 usually correspond closely to the world’s least religious countries—China and Japan being the major exceptions.173

Highly secularized countries also “tend to fare the best in terms of crime rates, prosperity, equality, freedom, democracy, women’s rights, human rights, educational attainment, and life expectancy,” according to the LA Times.174

Being skeptical apparently pays off.

WORKER BEES

One of the key pieces of propaganda we must fight against is the idea that a small number of people “deserve” immense wealth and power, because they work so hard, while the rest of society deserves to struggle for a lifetime because they are lazy bums. This concept is becoming pervasive in modern democracies, and its propagation is enormously destructive.

The Ayn Rand (author of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged) school of thought is that it is the ambitious visionaries who drive society forward and therefore should be allowed to keep the proceeds of their work; otherwise, they won’t invent things, and civilization will collapse. There is an element of truth in that. Where would we be without the innovations of Thomas Edison (well, Tesla) and Henry Ford? However, the theory falls apart if you think about it for a few minutes.

Wealth isn’t the only reason people accomplish significant innovations. Albert Einstein didn’t become particularly wealthy through his work and a great deal of the prosperity we enjoy in the twenty-first century is derived from his breakthroughs. Edison’s rival, Nikola Tesla, didn’t become wealthy either. His motivation was unraveling the mysteries of science (specifically electricity). The American inventor Buckminster Fuller spent his life designing innovative forms of housing, transport, and engineering without any thought of financial reward (according to his own testimony). So it isn’t true to say that all innovation is motivated by wealth. Many inventors simply want to make the world a better place.

The opposite school of thought to Ayn Rand was articulated very succinctly by Elizabeth Warren, Harvard Law School professor, Democratic Senator for Massachusetts and 2019 presidential candidate:

There is nobody in this country who got rich on their own. Nobody. You built a factory out there—good for you. But I want to be clear. You moved your goods to market on roads the rest of us paid for. You hired workers the rest of us paid to educate. You were safe in your factory because of police forces and fire forces that the rest of us paid for. You didn’t have to worry that marauding bands would come and seize everything at your factory… Now look. You built a factory and it turned into something terrific or a great idea—God bless! Keep a hunk of it. But part of the underlying social contract is you take a hunk of that and pay forward for the next kid who comes along.175

To extend her analogy—could this person have built their business if they had to hunt their own food? Build their own house? Make their own clothes? Teach their own children? I suggest they would have been way too busy trying to survive to pursue their business. On top of that, the customers of their business would also be too busy to be able to buy the business’s product or services, so the company would be a failure.

We live in a community, and every person in that community plays a vital role in keeping the community functioning. We might think of it as similar to a bee colony. Is the queen bee more critical than the worker bees? Without the worker bees bringing food into the hive, keeping the hive maintained, sealing honey, building honeycomb, carrying water, and keeping the hive cool, the queen bee would die. She needs the worker bees as much as the colony needs her to continue the species. It’s a relationship of mutual benefit, a symbiotic relationship.

The same could be said for human “worker bees” and the entrepreneurs or corporate executives, the “queen bees.” We need each other. One cannot survive without the others. Why, then, does one get paid 100 times or 300 times what the other gets paid? Do they work 100 times as hard or as long? Are their IQ scores 100 times higher (and, even if it was, can they take credit for having a high IQ or is it a gift of genetics)?

The queen bees in our society were educated in schools paid for by taxes, taught by teachers who, in turn, survived through being part of an integrated community. “No man is an island” as the English poet John Donne wrote.

Maybe we even need psychopaths? Perhaps many of the great inventors, the ones who didn’t care what people said about them, who ignored their families in pursuit of their vision, were psychopaths?176

OF THE PEOPLE, BY THE PEOPLE

Political parties, like every other organization, have one overpowering primary instinct—to survive by retaining their power at all costs. They all evolve and morph over time, abandoning, if necessary, their original policies and principles, to survive perceived changes in the realities of the political climate. Like corporations and religious organizations, they obey the laws of “organizational Darwinism.” Over time, their values, policies, and platforms evolve to reflect the changing times. In some cases, this has been a great thing—for example, up until the 1970s, both of the major political parties in Australia supported the White Australia Policy (where only white Europeans could lawfully immigrate to Australia), a fact I still find shocking.

There is no reason to think that political organizations would work any differently to the other kinds of organizations we have already explored—people who rise to the top of the party will have a natural incentive to try to preserve their power by maintaining the control that the party has.

In Western democracies, we’ve been led to believe that our governments are “of the people, by the people, for the people,” as Lincoln put it. While this may be a beautiful sentiment and something we should aspire to, the frequency with which people seem to fall for lies told by our governments suggests that might be a naïve view.

Today most Western democracies are dominated by a handful of political parties (themselves controlled by a handful of corporate interests) that have become increasingly difficult to tell apart. The parties on the left have drifted, at least on many economic issues, to the right; in response, the parties on the right have had to move to the extreme right (especially in terms of their rhetoric) to keep a gap between them.177 The culmination of decades of the U.S. Republican Party’s drift to the right was the 2016 presidential win of authoritarian billionaire Donald Trump.

And it’s happening around the world. In Australia, according to one analysis:

The Australian Labor Party reflects this drift, now occupying a space to the right of the 1980s Liberals. The debate between the two primary parties, however heated, is within narrowing parameters. The two parties are now closer together than at any other time. The clash of economic vision of earlier campaigns is absent. It’s no longer about whether the prevailing neoliberal orthodoxy is actually desirable, but merely a question of which party can manage it best.178

Meanwhile, another form of political organization, the union movement, has been systematically weakened worldwide. In the U.S., union membership has fallen to 11.3 percent of all workers. In the private sector, unionization fell to 6.6 percent, down from a peak of 35 percent in the 1950s.179

In Australia, the decline is even more severe—from nearly 65 percent in 1948, to around 15 percent today.180

As a result of these and other factors, including off-shoring of jobs and automation, growth in real wages in most developed economies (Australia is an exception, thanks mainly to our mining boom) has mostly stagnated since the 1980s. This is seen most clearly in the United States—the world’s second-largest economy (after socialist China).181

What happened?

One factor was the aforementioned deliberate association of raw, unbridled capitalism with Christianity. There also seems to be a connection between the rise of corporate wealth and influence in the late twentieth century and the decline of progressive politics. According to Julian E. Zelizer, a historian at Princeton University:

The Democratic Party in the 1990s ran away from much of the robust economic vision that had defined the party since the progressive and New Deal eras. Many Democrats accepted some of the market-based premises of conservative politics, backing away from central parts of their core domestic agenda like progressive taxation and economic regulation. The growing power of corporate interest groups in Washington, which mobilized huge teams of lobbyists and threw around sizable campaign donations, made both parties less willing to hear demands for redistributive public policy.182

Regulatory mechanisms created after the Great Depression, designed to prevent its recurrence, were systematically dismantled and destroyed by successive governments of all stripes after 1980. Ronald Reagan‘s attack on America’s progressive tax system, which he claimed came “direct from Karl Marx,” culminated in his historic reduction in corporate and individual tax rates in 1981, which ultimately benefited wealthier Americans.

This led to today’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge, organized by Republican strategist Grover Norquist, “the high priest of Republican tax-cutting,” which asks all candidates for federal and state office (in the United States) to commit themselves in writing to the American people to oppose all net tax increases and punishes those who do not.183

Consolidation of corporate media ownership and the rise of television as the primary entertainment and news medium led to a population that could be manipulated more efficiently than ever before.

In the United States, the Republicans and the Democrats have swapped ideologies over the last 150 years,184 with the Republicans becoming more conservative while the Democrats have become more socially liberal than they once were (supporting gay marriage, abortion, etc.), but more economically conservative (the financial industry regulations put into place under FDR in the 1930s were dismantled under Clinton in the 1990s,185 support for free trade agreements, Obama’s continuation of Bush’s tax cuts for the rich, etc.). When it comes to foreign policy, it gets harder to tell them apart—both tend to support significant Pentagon budgets, financial and military support for apartheid Israel and Sunni fundamentalists, journalist-executing Saudi Arabia, and trying to clamp down on any nation that doesn’t fully accept American domination of global trade. And they both tend to fully support the surveillance state apparatus (the NSA, FBI, and other agencies) while taking a hard stance on government whistleblowers (e.g., Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, and Reality Winner).

The late American political theorist Sheldon Wolin, in his book Democracy Incorporated,186 coined the term “inverted total-itarianism” to describe America in the early twenty-first century. Journalist Chris Hedges defines inverted totalitarianism as a system where corporations have corrupted and subverted democracy and where economics trumps politics:

Inverted totalitarianism is different from classical forms of totalitarianism. It does not find its expression in a demagogue or charismatic leader but in the faceless anonymity of the corporate state. Our inverted totalitarianism pays outward fealty to the facade of electoral politics, the Constitution, civil liberties, freedom of the press, the independence of the judiciary, and the iconography, traditions and language of American patriotism, but it has effectively seized all of the mechanisms of power to render the citizen impotent.187

As media ownership has been concentrated into the hands of the relative few (something all of the major parties in Western democracies have allowed to happen188), and countries have produced more and more billionaires and wealthy corporations with the ability to swing elections, the policies and practices of political parties have had to pander to the pressures placed upon them by the powerful.

This is a natural outcome of capitalism predicted by Karl Marx. He predicted that capital would be accumulated by a small number of people who would achieve economies of scale, which would, in turn, lead to further concentration and centralization of wealth into fewer and fewer hands, with competition leading to the big firms killing or eating the smaller firms, thereby destroying the competition.

Marx explains:

It is concentration of capitals already formed, destruction of their individual independence, expropriation of capitalist by capitalist, transformation of many small into few large capitals.… Capital grows in one place to a huge mass in a single hand, because it has in another place been lost by many.… The battle of competition is fought by cheapening of commodities. The cheapness of commodities demands, ceteris paribus, on the productiveness of labour, and this again on the scale of production. Therefore, the larger capitals beat the smaller. It will further be remembered that, with the development of the capitalist mode of production, there is an increase in the minimum amount of individual capital necessary to carry on a business under its normal conditions. The smaller capitals, therefore, crowd into spheres of production which Modern Industry has only sporadically or incompletely got hold of. Here competition rages.… It always ends in the ruin of many small capitalists, whose capitals partly pass into the hands of their conquerors, partly vanish.189

And this is precisely what happened:

Today, mom-and-pop shops have been replaced by monolithic big-box stores like Walmart, small community banks have been replaced by global banks like J.P. Morgan Chase, and small farmers have been replaced by the likes of Archer Daniels Midland.190