Grey’s Grotesqueries

YOUR EYES WILL LEAVE YOUR BODY: COMING LATE TO ULTRA Q

“For the next 30 minutes, your eyes will leave your body and arrive in this strange moment in time.” So begins one of the Rod Serling-like voiceover intros to Ultra Q, a show I had never even heard of until just the last couple of years.

Like a lot of people my age, I grew up with Godzilla. The big lizard was probably my first favorite monster which, given that John Langan once called me “the monster guy,” seems like a big deal. I watched Godzilla’s exploits in flicks that were broadcast on some local channel Saturday mornings; owned VHS copies of King Kong vs. Godzilla and Godzilla vs. Megalon; pored over images of Godzilla and their foes in those orange Crestwood House monster books; even begged my parents to buy me a knock-off Godzilla toy from the gift shop at the Wichita Zoo—a toy that still sits on my shelf to this day.

Even then, though, the Godzilla films I watched were being beamed to me from another age. The ones I was exposed to were primarily from what is known as the Showa Era, the earliest batch of Godzilla pictures, made between 1954 and 1975, while I was watching them in the ‘80s.

With that background, I can’t tell you when I first became aware of Ultraman, but it must have been early. I never watched the show when I was young, though. Ultraman’s sleek, humanoid design appealed less to my child’s sensibilities than Godzilla’s spiny, squamous, reptilian silhouette. I think that, as a kid, I probably saw Ultraman himself as too much of a “good guy.” He fought monsters; Godzilla was one.

That said, I probably would have watched Ultraman, and gladly, perhaps voraciously, had it been available, but we didn’t get a channel that showed it. I wouldn’t see an episode until many years later, after most of the events of this column had already unfolded.

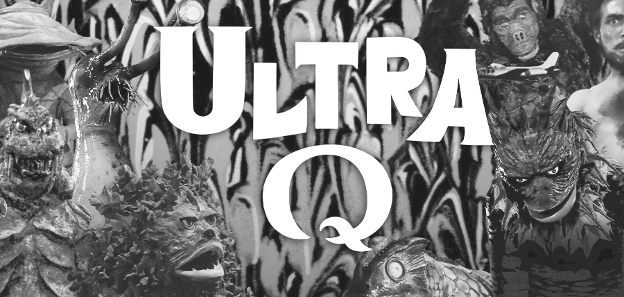

Fast-forward a few decades from that kid eagerly crouched on the deep-pile of my parents’ living room watching Godzilla movies on a big, wood-paneled TV, and I see a black-and-white gif on Twitter. In it, a man hugs close to a rock face as the glowing eyestalks of a giant snail slowly rise to tower over him. It was basically everything I ever wanted to see in a show, all contained in the few repeated frames of that gif.

A little digging told me that the image was from a series called Ultra Q; a Japanese tokusatsu show that had originally been broadcast in 1966. Created by Eiji Tsuburaya, the special effects pioneer who was partially responsible for Godzilla, the show featured plenty of kaiju – which were, of course, popular in Japan at the time – but was intended to ape American sci-fi shows like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits.

Unlike Ultraman and the rest of the half-century-long (and counting) franchise that would follow it, the protagonists of Ultra Q were just regular folks—recurring characters included a couple of pilots and a female reporter, played by Hiroko Sakurai, who reappeared as a different character in Ultraman that same year.

In the course of the series’ 28 episodes, these regular people encountered decidedly irregular events—the original title of the series was going to be “Unbalanced.” Often, these events involved giant monsters—usually, but not always, from outer space—but they also ran afoul of gigantic primordial plants, honey that caused creatures to grow to abnormal size, a girl who could astrally project, and, in perhaps the show’s most overtly horror-themed episode, the abandoned mansion of a baron who had transformed into a giant spider.

From that gif on Twitter, I tracked down Ultra Q, first on DVD from Shout Factory, later on Blu-ray from Mill Creek. Finally watching the series, which was thrown together under tight time constraints, often repurposing suits and props that had previously been used in feature films, was a decidedly mixed bag. Some episodes were too childish or grating, but when the show was at its best, it hit all of my buttons in a way perhaps no other television series ever has. Here was something combining the speculative thoughtfulness of The Twilight Zone with the rubbery antics of early tokusatsu cinema, not to mention a team of unlikely paranormal investigators.

In just about every episode, I was guaranteed some kind of weird monster, many of whom later reappeared and entered Ultraman lore, but I was also treated to some surprisingly ambitious concepts. Take, for example, the time-jumping alien invaders in “Challenge from the Year 2020” or “The Disappearance of Flight 206,” which essentially prefigures Stephen King’s The Langoliers, with an extradimensional walrus in place of the chainsaw-jawed Pac-Man monsters of that TV mini-series.

Ultraman entered production at the same time as Ultra Q, and the two series premiered the same year. It’s obvious, looking back across decades that are filled with subsequent Ultraman shows, which one took off the most. I picked up a bunch of the Ultraman series that Mill Creek has been releasing, too, but, at the time of this writing, haven’t watched more than a few episodes. It’s not that I don’t enjoy them—I like the monsters and the models, all the tokusatsu stuff—but they aren’t, for me, what Ultra Q was.

Part of it is that there’s just something about the old black-and-white footage of shows like Ultra Q and the American sci-fi series it was emulating. Not just the stark, noirish chiaroscuro of shadow and light, but also that sense of looking at something from another time. Something beamed to you from the past and yet made to live in the here and now; the antiquarian bent that so typifies the ghost story.

Ultimately, though, it may be the very presence of that super-heroic central figure which ensures that Ultraman and all those series that follow it will be something altogether different from Ultra Q. In the Dark Horse Book of Monsters, first published in 2006, there’s a loving paean to the classic Jack Kirby monster comics of the 1950s—another phenomenon that I came to late and that was, in fact, being published almost contemporaneously with Ultra Q – penned by Kurt Busiek and Keith Giffen.

In it, retired adventurer Riff Borkum is relating the story of his last thrilling escapade – traveling to the Himalayas in search of “Kungoro, the Monster of the Snow,” while back home in New York, a different kind of story is unfolding.

The conflict with the strange monster is ultimately upstaged by the arrival of superheroes, making diegesis of what was happening in the actual comic book marketplace, as the popularity of tights and capes comics edged out stories like the Kirby monster tales.

“Now the wonders are the heroes,” Borkum says, in the story’s melancholy final pages. “Saving the earth from despots, alien races and more. And mankind … mankind just watches. And sometimes applauds.” Words that may have been reflecting on a past gone by but that feel uncannily prescient more than a decade later, when superhero movies dominate a box office once controlled by other fare.

The sentiment echoes one of my favorite lines from any film, the one that gave my second short story collection its title. Boris Karloff, playing a thinly fictionalized version of himself in Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets (1968), another near contemporary to Ultra Q, laments that, “My kind of horror is not horror anymore. No one’s afraid of a painted monster.”

There’s a wistfulness to both speeches, but not necessarily condemnation. The world moves on, and we’re lucky enough to be able to come late to some things, even if we didn’t grow up with them.

I have no doubt that I’ll have fun with Ultraman and its various spin-offs, and there’s no denying which series was more popular and influential. But, just as some part of my monster-loving heart is always with Kirby’s four-color creatures and Karloff’s “painted monsters,” some part of me will always be traipsing through the black-and-white sets of Ultra Q, waiting for my eyes to leave my body and arrive in that strange moment in time… . §