![]()

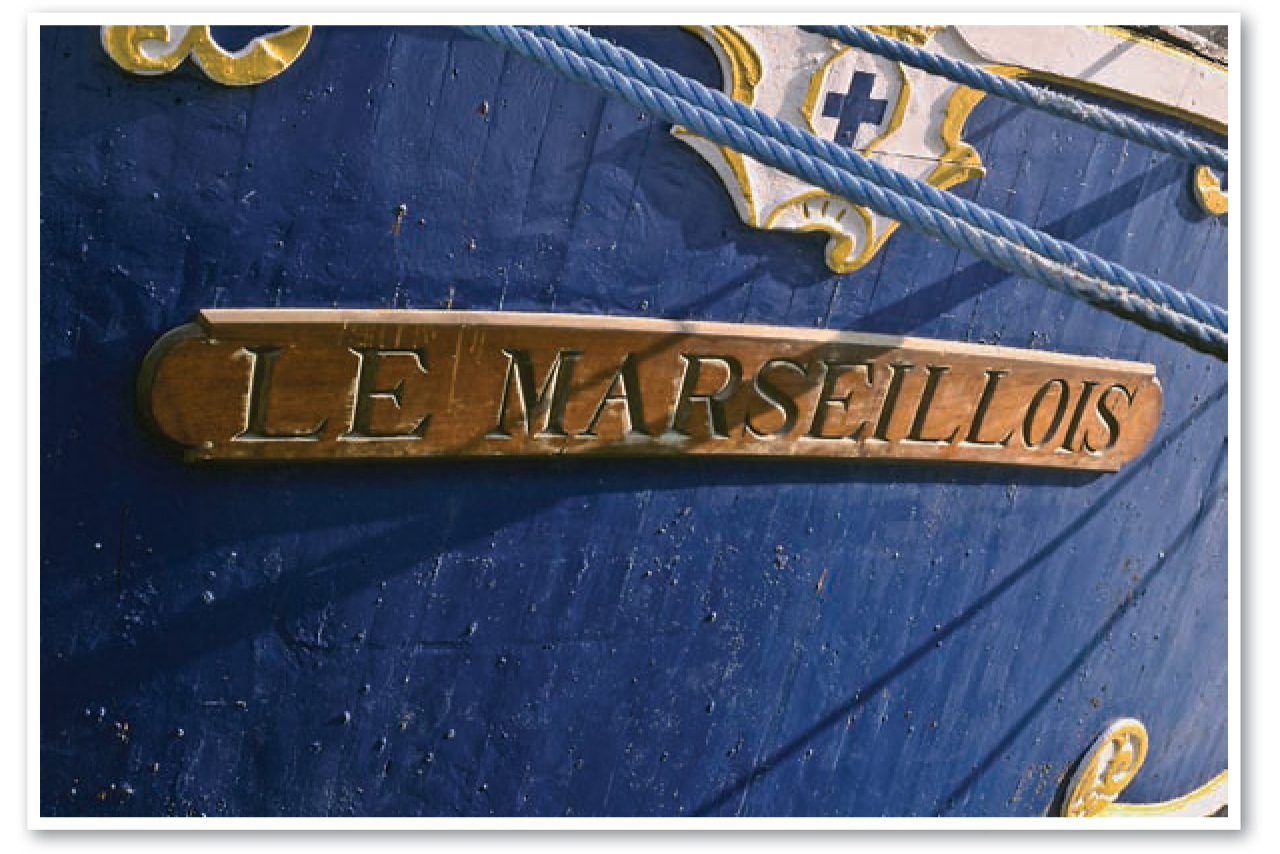

PLATE FORTY-SEVEN — Stern, Tall Ship

![]()

A TRUE KARMIC FORCE is supposed to build up its strength through centuries of both evil and good, in order to prevent its transmigration into another and lesser form, and this may well explain why Marseille has always risen anew from the ashes of history. There seems to be no possible way to stamp it out. Julius Caesar tried to, and for a time felt almost sure that he had succeeded.

Calamities caused by man’s folly and the gods’ wrath, from the plagues ending in 1720 to the invasions ending in the 1940s, have piled it with rotting bodies and blasted rubble, and the place has blanched and staggered, and then risen again.

It has survived every kind of weapon known to European warfare, from the ax and arrow to sophisticated derivatives of Chinese gunpowder, and it is hard to surmise that if a nuclear blast finally leveled the place, some short dark-browned men and women might eventually emerge from a few dark places, to breed in the salt marshes that would gradually have revivified the dead waters around the Old Port . . .

Meanwhile, Marseille lives, with a unique strength that plainly scares less virile breeds. Its people are proud of being “apart,” and critics mock them for trying to sound even more Italianate than they are, trying to play roles for the tourists: fishermen ape Marcel Pagnol’s Marius robustly; every fishwife is her own Honorine.

PLATE FORTY-EIGHT — Scene From Pagnol

The Quai des Belges is the shortest of the Port’s three shores, at the head, the land end, of the little harbor. Like all centers of life past and present, it is concentrated . . . with careful room for the fishermen, to chug in six or seven mornings a week to set up their rickety tables in the casual market that strings out along the wide sidewalk.

PLATE FORTY-NINE — Marseillaise

The native women of Marseille, the ones who are unmistakably of this place and no other that I have seen or read about, are short and trimly wide . . .

As girls they have a slim beauty that soon passes into what they will be for the rest of their lives . . .

They may develop paunches, the tidy kind that look made of steel, and among the lot of them there is never a snub nose, but instead the kind that grows stronger and beakier with time. Their arms and legs stay shapely enough, thanks surely to hard work, and their skins become like well-soaped leather, thanks perhaps to good olive oil and garlic and an occasional pastis, all taken by mouth in daily doses. (Tomatoes are also thanked for continuing their female vigor, according to many of their mates . . .)

PLATE FIFTY — Marseillaise

In all the Marseillaises seem almost a part of their craggy land, like the thick trunks of the most ancient olive trees on the hills behind the city. And still they are from the sea, so that they smell of salt, and of what they eat and what they work with, but never of old sweat.

PLATE FIFTY-ONE — Fresh Catch

During the Market hours there, men sold their catches, too, but it was the women who dominated, at least in decibels. The men simply stood behind their piles of gleaming sardines, slithery small octupi, long eels trying to get back into the dirty Port water, greyish-pink shrimps hopping within their pyramids of myriad brothers.

PLATE FIFTY-TWO — Fisherman, Quai des Belges

PLATE FIFTY-THREE — Fish Heads, Quai des Belges

They smiled and chatted in a detached way as they scooped the catch into newspaper cones, or whacked something into immobility for its last ride toward the kitchen, but they seemed poised for escape from all the selling end of their game. That was for the women. Once the fish got to shore, the men were set to head out to sea again . . . les pescadous.